Tell It 'Slanted': An Approach to Writing My Memoir

Poet and playwright Robert Yeo shares his approach to writing his memoir, choosing to “artfully organise [it] in the form of a ripple… While being linear, I can, at the same time, be circular. Whilst interrogating the past, I am still able to confront the present”.

Routes and Roots

First, let me explain the title I have chosen for my memoir, Routes. I am told the American pronunciation is “routs”, but obviously that is not what I have in mind. I wanted a pun that suggests “roots”, a reference first of all to Alex Haley’s 1976 groundbreaking book Roots: The Saga of an American Family.1 In that book, Haley goes back to his family’s early roots in Africa and discusses how the first ancestor was transported to America to work as a slave. The book focused on “roots” to mean “origins”, reinforced greatly by the television series that followed the publication of the book. Yes, I am interested in my roots in that sense, and it shows in my accounts of the lives of my parents and grandparents.

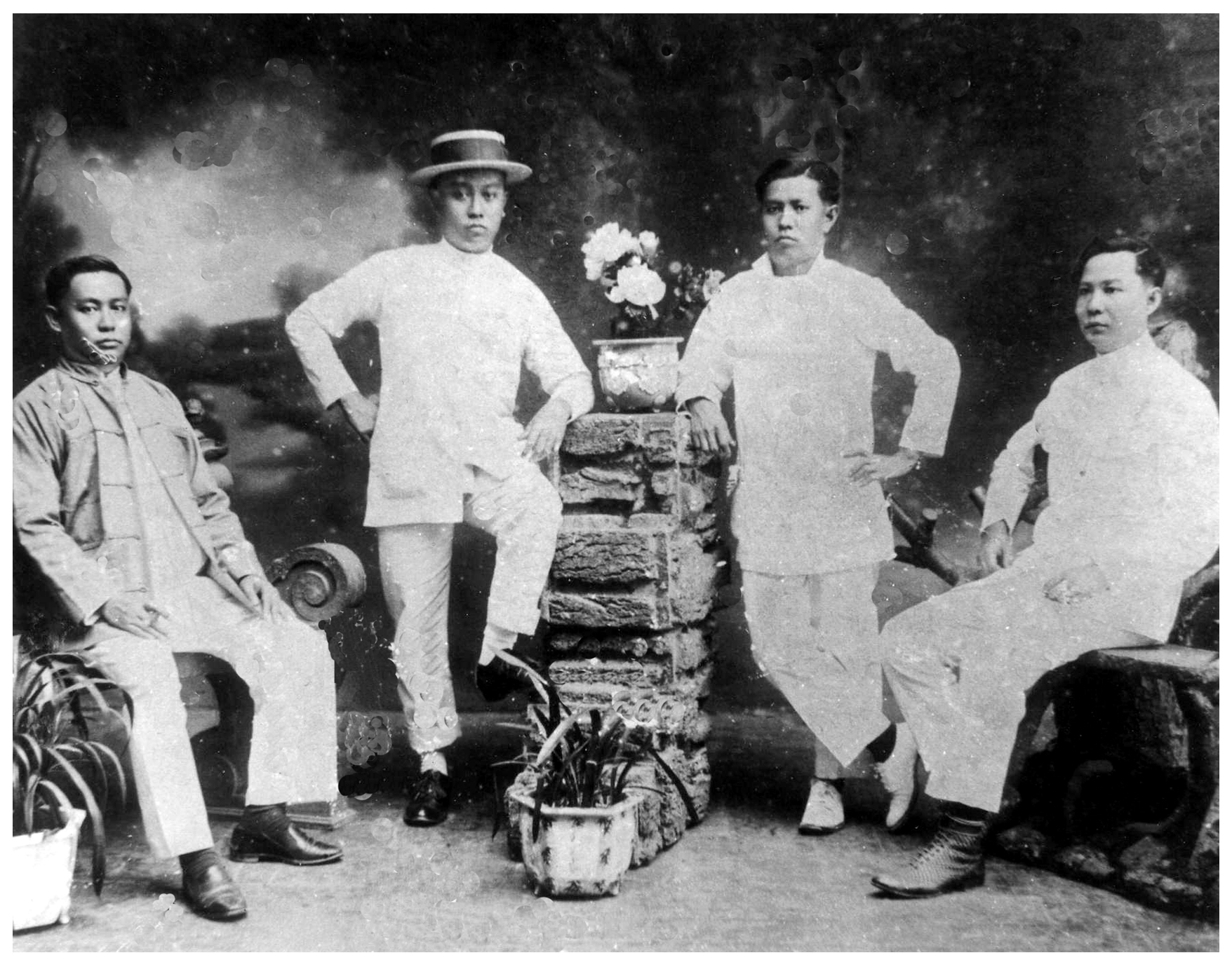

At the same time, I am keen to use the title Routes to refer to the physical journeys that my grandparents made. My reading of history tells me that the ancestors of the Chinese in Southeast Asian countries came mostly from southern China, namely the provinces of Fujian, Guangdong and Guangzhou.

Whether the migrants came overland or by sea, some had to choose their routes, while others had their routes chosen for them. From villages and ports in China in the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries, they left for Southeast Asia: Vietnam, Laos, Burma, Thailand, Malaya, Singapore, Indonesia, Borneo and the Philippines. In the case of my paternal grandparents, their route took them from southern China to Sarawak and then to Singapore. For my maternal grandparents, they left southern China for Melaka and then eventually settled in Singapore.

My grandparents’ journeys suggest a third meaning to “routes”: choice. Did the migrant have a choice as to where he/she would go after leaving southern China? Going southeast would have brought them anywhere, to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaya or Singapore, and so on. Was he/she pushed by domestic factors like poverty or war? Or did the allure of a new life outside China beckon?

Doing It Differently

Because an autobiography traditionally starts with the author reminiscing about his/her life starting from birth, the first constraint is the adherence to sequence; he/she must observe chronology in the storytelling. He/she is acutely aware that he/she is writing about the past in “recall” mode. This is a challenge as we all know that we have a selective memory.

Following a chronological method may be a less-than-exciting necessity, but it enables me to grasp time. I do acknowledge that I live in the present as much as I do in the past. Quite often, they are in fluid fusion or collision. So, as art organises the chaos of my life, I have tried to artfully organise my memoir in the form of a ripple. Herein lies the difference between my memoir and most of the rest: While being linear, I can, at the same time, be circular. Whilst interrogating the past, I am still able to confront the present.

The Ripple Effect

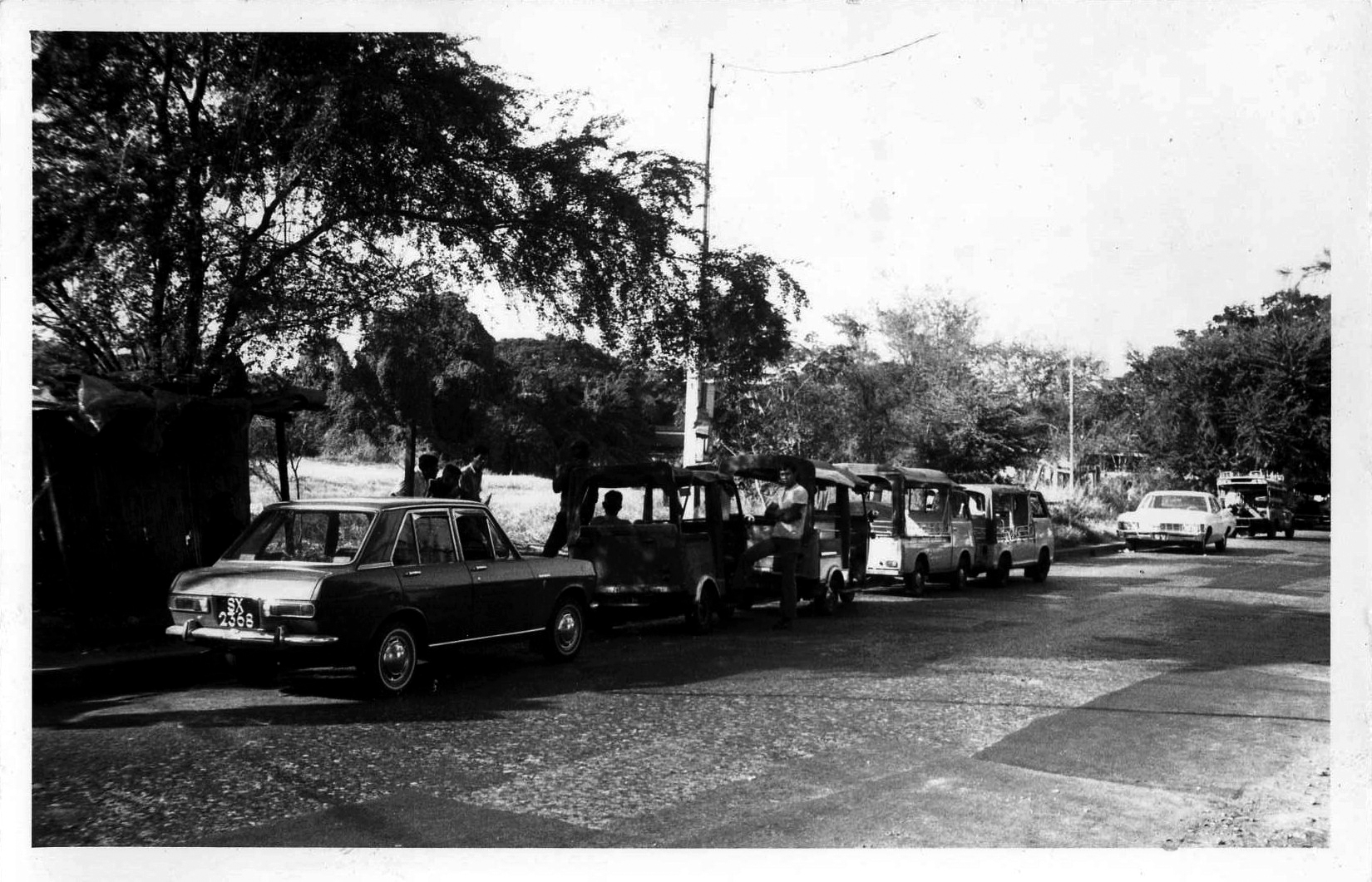

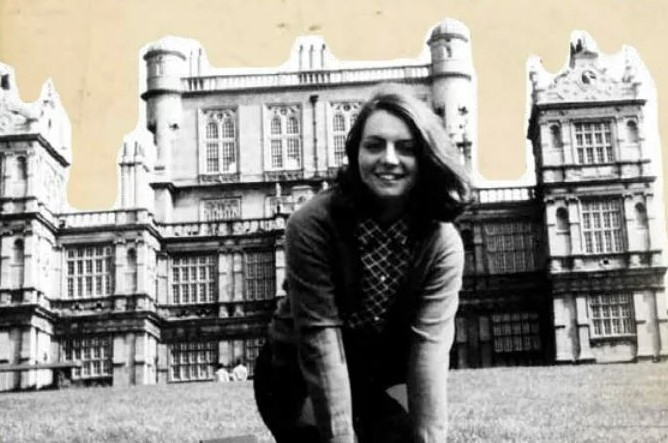

At the core of my book is the self; the conscious self. I start with my experience, my earliest memory and then “ripple out” to explore how the self is shaped by events in my community, my country and the rest of the world. I am able to do this because of the life I had lived up to 1975. Born in Singapore in January 1940 as a British subject, I went through the Japanese Occupation from 1942 to 1945, self-government in 1959, independence in 1965, studies in London, England, from 1966 to 1968 and work in Bangkok, Thailand, from 1970 to 1971. Given the trajectory, I feel that it was inadequate to write about myself without inquiring how my life is determined by the ripples. As well, at a certain time in 1974, I felt I was in a position of not only being passively influenced by external events, but also being able to directly influence events as my playwriting career prospered.

I felt absolutely privileged that in the first half of my life so far, I was witness to extraordinary happenings. First, how many people get a chance to witness his/her homeland’s transition from a colony to a nation? On page 166 of my memoir, I quote Lee Kuan Yew when he was taking the oath as prime minister of Singapore on 9 August 1965: “that as from today, the ninth day of August in the year one thousand nine hundred and sixtyfive Singapore shall be forever a sovereign, democratic and independent nation”. Two, many people get to go to London for a variety of reasons but how many actually were there at a time of glorious tumult in a world capital – when women upped their skirts and young people downed old values, smoked hash, loved freely, and all this happening while the Beatles were redefining pop music? Third, not many people in Asia, influenced by American soft power in the arts – movies, comics, jazz – got to witness the same power humiliated militarily as they pulled out of Saigon, Vietnam, on 30 April 1975, thus ending the Vietnam War. These experiences have shaped my life for the better.

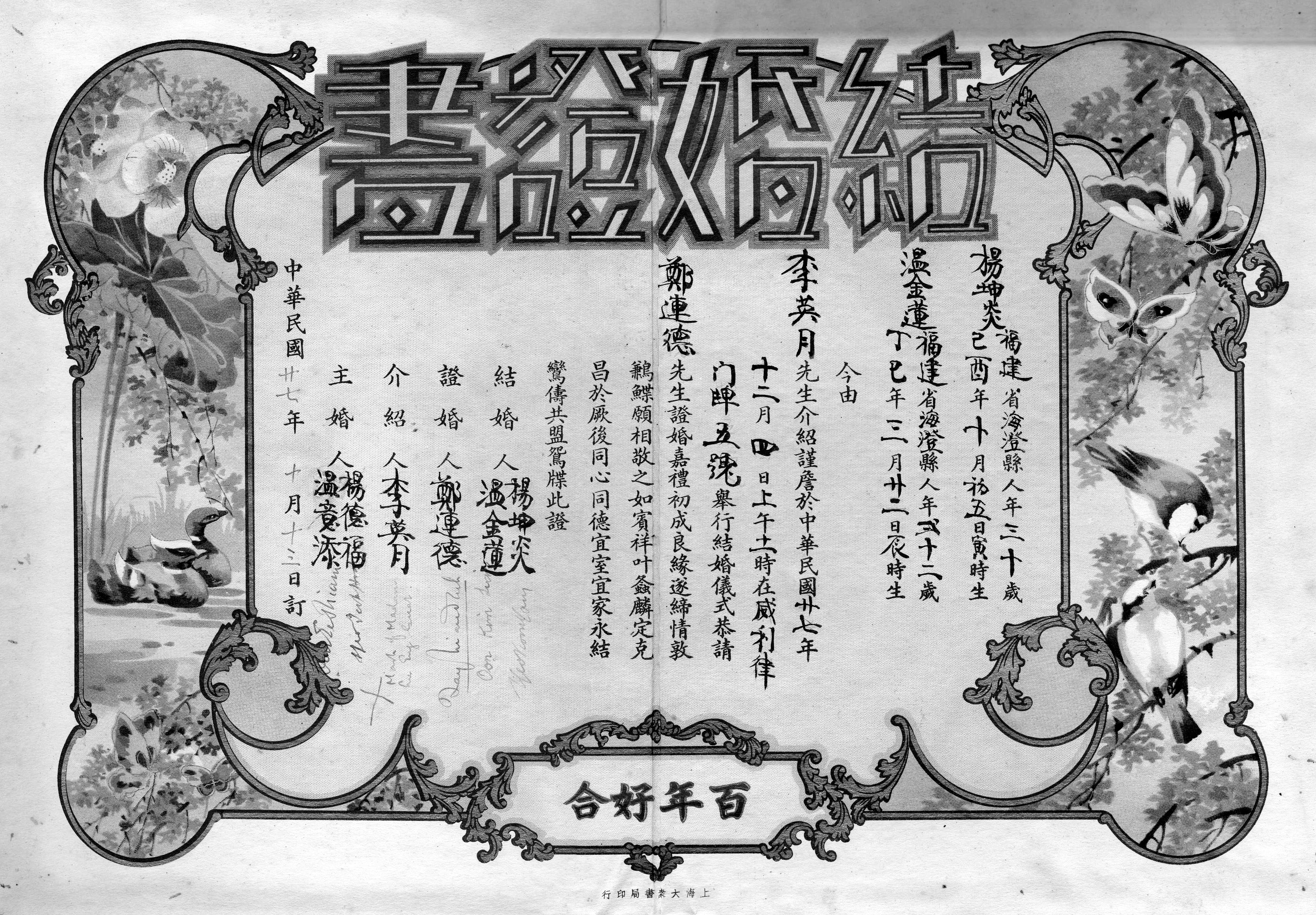

My self, of course, includes family. Given my Peranakan heritage – and such a heritage has a long history in Singapore and Malaysia – it is inevitable that I would have to include the stories of the two generations prior to mine, as well as my own. In writing about my generation, I however found it easy to link it to my parents and my paternal and maternal grandparents. Without this “flashback”, how else can I do justice to the past in a filial way? On reflection, I realise that my book is a Confucian act of filial piety by the eldest son in my family: Grandfather Teck Hock was the first son in his family, my father Koon Yam was the first son in his, and I am also the first son of my father.

Whilst interrogating the past, I can still confront the present. In the moment – in the “now” – I feel free to shift to the past. It becomes apparent, as I proceed, that I am deliberately interrupting my sequential narrative by inserting relatively long perorations; for examples, see those found in pages 47–52, on my maternal grandma and her family, and pages 261–264, where I review former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s book The Malay Dilemma.2 I realised, whilst signing books at the launch in August 2011, that in doing this, I was deliberately challenging the current digital generation – who is used to short sound bites – to a long read. My book, at 384 pages, and with only about 100 illustrations, is a relatively long one!

Incorporating the Epigraph, Intertextual and Collage Techniques

As a consequence of my background as an academic and writer, I incorporated the techniques of epigraph-writing, intertextuality and collage into my book. They collectively testify to my interests as both an extensive and intensive reader. As well, they demonstrate that reading has been for me always an emotional encounter and seldom a passive activity. Consider the two following instances. First, my discovery of Edward Fitzgerald’s poem “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”, which is recorded on pages 62–63. This was instrumental in reinforcing in me a passion for reading and writing poems. Second, my timely reading in 1970 of the incendiary book, The Malay Dilemma, by Mahathir Mohamad. I wrote then:

The epigraphs, of which there are two in each chapter, are not merely incidental. They do several things: Convey, directly or indirectly, the intentions of my book or chapters; provide concrete evidence of my having read widely; and chart the periods in which the readings happened. The quotations and extracts from my poems, plays and fiction demonstrate my development as a writer in these genres. In addition to excerpts, I have included whole works, complete poems and a short story.

I have done the above intertextually. Intertextuality is a technique I am very partial to as it establishes dynamic, symbiotic relationships between books. For example, I quote E.M. Forster’s Howards End3 – where he wrote the epigraph “Only Connect” – in one of my epigraphs.

Sometimes, too, I have juxtaposed these insertions in such a way as to create a collage, leaving my reader to make the connections; see, for example, pages 370–374.

It will also be apparent, from what I have written in this section, that I have employed in Routes a few familiar techniques used by fiction writers. I am sure many who write autobiographical accounts would also be able to utilise the epigraph, intertext and collage as strategies. As a writer and academic for whom these aspects of literary theory are common, I guess I have an advantage.

I hope all these – including the candour of my revelations, the sensual as well as the intellectual, and the embracing, servicing use of anecdotal articles, diary entries, epigraphs, letters, fiction, poems, plays, reviews (of books and plays) and quotes from books and reports – will convey the impression of my whole person in the years from 1940 to 1975. Oh yes, the illustrations! They – over a hundred of them – interact dynamically with the text as part intimate commentary, part revelation, part interrogation; please scrutinise them carefully. As the great American poet Walt Whitman wrote after publishing the first edition of his masterpiece Leaves of Grass:

Robert Yeo

Robert YeoPoet and Playwright