The Historical and Cultural Influence of the Record Industry of Singapore, 1903 to 1975

Over a period of 75 years during the last century, Singapore was one of the most important centres for the record industry in Southeast Asia.

Despite its considerable economic and cultural importance, there has been very little published about the Singapore record industry. So far, there has not been a single book on this subject and the two journal articles that have appeared over the last 30 years1 cover only part of the story.

By 1903, when the first commercial recordings made in Asia by Fred Gaisberg appeared, Singapore was already a thriving centre of trade and commerce in the region. It had been exposed to Edison’s new invention of the phonograph in 1879,2 and in 1892 the Improved Phonograph (which was the model for the first commercially available machines) was demonstrated in Singapore by Professor Douglas Archibald,3 who had travelled from Australia where he had been giving lectures and demonstrations of the device since 1890.4 This early phonograph, which played wax cylinder records, had first been advertised in Singapore by Robinson & Co. in the same year,5 and Emile Berliner’s gramophone, which played disc records, was being sold in Singapore by John Little & Co. Ltd. in 1899.6

These 19th-century developments demonstrate that Singapore was fully open to all the latest scientific developments that made possible the development of a global record industry in the coming decades. Together with its geographic location, this meant that Singapore was well placed to function as a logistical and administrative centre for the new record industry. It was also significant that Gaisberg planned his recording expedition in a way that made full use of Singapore as a gateway to the region.

There are no contemporary accounts published in Singapore newspapers of Gaisberg’s visits in 1902–03. This is an indication that, unlike the various public exhibitions of the latest inventions mentioned above, the first recording sessions in May 1903 were the private operations of a global business enterprise, conducted with the intention of making a profit, and were not considered newsworthy, although they are now regarded as an important historic event. Despite the lack of contemporary reports, the details are known from Gaisberg’s diaries.7 This account shows that Gaisberg had already established logistical procedures that became a model for the way in which the record industry would operate in the region over the following decades. Even in the earliest days, Singapore was established as a key location from which other potential markets in the region were accessed.

Another procedure introduced by Gaisberg was that when he first arrived in Singapore in December 1902, he made arrangements for suitable artists to be available for recording when the expedition returned. It became standard practice for the local agent of a record company to arrange for the artists to be recorded to be available in Singapore when the recording engineers and equipment arrived on their periodic visits, and he also worked with them to select a suitable repertoire in advance. Artists would frequently travel from their home cities in Malaya or Java to Singapore for this purpose.8

This method of arranging recording sessions in Singapore was used until the 1950s. The planning would take place over several months so that when the recording engineer arrived, many recordings could be made in a relatively short time. In those days there were no permanent recording studios in Singapore or anywhere else in Asia. Such places only existed in the main centres of the record industry such as New York or London. In smaller or more remote locations such as Singapore, a hall or rooms in a hotel were normally rented for a few days or weeks for recording purposes as such facilities would not be needed again until the next visit of the recording engineer (which was usually only once a year at most).

The earliest known published account of a Singapore recording session in 1912 refers to a “temporary recording department”,9 and the earliest known report in a Singapore newspaper of a local recording session in 1929 notes that two rooms at the YMCA “were utilised by the Columbia Gramophone Co., the local agents for whom are Messrs. Robinson Piano Co. Ltd., as a studio for recording”.10

The type of recordings that were made also did not change much until the 1960s. The first recordings in 1903 were of Malay songs, which were followed soon after by recordings of Chinese opera and dialect songs. The record companies operated on the principle that they did not record material in one location that could easily be made in another location with a higher standard of performance. This meant, for example, that in Singapore the most highly developed performers were those singing material unique to Southeast Asia and English-language songs, and they were hardly ever recorded until the 1960s since the companies could import a wide range of English-language performances by famous artists from Britain, Europe or America for those who wanted such recordings.

There were only a handful of exceptions to this rule. For example, the first known English-language records made in Singapore were recorded in 1932 for the Singapore Musical Society.11 The records were made at Victoria Memorial Hall by the Singapore Cathedral Choir and E. A. Brown.12 Another exceptional case was a group of English-language records made for educational purposes in 1936.13 Otherwise, the vast majority of the recordings made in Singapore from 1903 until the early 1960s were Malay or Chinese songs.

The Gramophone Company was not only the first to make recordings in Singapore in 1903, it dominated the market up until the 1960s (after 1931 in the form of EMI). In the early years of the record industry, the competition was intense for new markets as companies fought to expand worldwide, and following Gaisberg’s initial recording expedition to the region in 1902–03, other companies sought to add Malay, Chinese and other Asian recordings to their catalogues. Within a few years, there were many labels releasing material recorded in Southeast Asia; in this way, Singapore quickly became a hub for the record industry as an administrative, distribution and recording centre for the whole region.

The Beka Record Company also recorded in Singapore in January 1906. They returned in 1909, and by the 1920s, the company was making regular visits for recording. The Beka label was discontinued in 1934.

Another company that briefly made early recordings in Singapore was Lyrophon. Its sessions seem to have taken place in 1910 and again in 1913. The label’s agent in Singapore was Chop Teo Chiang, but this arrangement ceased in 1914.

The Columbia Graphophone Company was active in Singapore from 1912 onwards, but the company went through several changes of ownership before the 1930s (when it became part of EMI); as a result, its recording operations were rather sporadic. Its last known recording session as an independent entity was in 1929.

The main label of the Lindstrom group (based in Berlin, Germany) was Odeon, which began recording in Asia in 1905. Odeon was acquired by Columbia in 1926 and also subsequently became part of EMI.

Deutsche Grammophon was another German company that conducted recording sessions in Singapore starting in 1927, with issues on the Hindenburg, Polyphon and Parlophon labels until 1931. They also made recordings for the Pagoda label, which began in 1930 as a venture of Mong Huat & Co., which had been the distributor for the Gramophone Co. since 1927.

In 1927, the British company Edison Bell made some recordings for local record distributors that wanted their own labels. The Quek Swee Chiang, Teck Chiang Long and Teo Chiang records were early examples of labels that catered to niche markets such as Chinese dialect opera records in Hokkien or Teochew. All these labels were short-lived and were discontinued in 1928. But Edison Bell retained an interest in the local market and produced some 8-inch records of Malay songs on the Edison Bell Radio label between 1929 and 1930.

There was also a very short-lived Chappell label produced by the British Crystalate Company in 1930.

The Great Depression of the early 1930s put an end to much of the recording activity that had flourished in Singapore since 1903. Only EMI continued regular recording sessions (which were released mainly on the label His Master’s Voice). By 1934, the economic situation had improved sufficiently for a new label, Chap Kuching, to be launched for Malay records by Moutrie & Co.,14 which was the agent in Singapore for EMI. This label continued until 1939 and was initially supervised for Moutrie by Tom Hemsley.

Apart from Chap Kuching, the other new labels that appeared in the mid-1930s were for two small private operations. These were Limophone (1935) and Foo Ann (1935–38). The success of Chap Kuching seems to have encouraged Tom Hemsley to leave Moutrie, and in 1937 he started his own label, Chap Singha,15 which ran until 1941. In 1938, he also launched the Delima label,16 which specialised in Javanese singers.

EMI also seems to have felt more confident about the local market in the second half of the 1930s; in 1937, it relaunched its Columbia label with a new series for Malay records. Columbia also issued a few local Chinese records. His Master’s Voice continued to release both Malay and Chinese dialect records on a regular basis up until 1941.

Two more labels introduced in 1939 were produced in Shanghai by Pathe Orient Ltd. These were Canary, which was aimed at the Southeast Asian market, and Tjap Angsa, which targeted more specifically the Java market. Both were distributed in Singapore by Tom Hemsley.17

The Japanese invasion in 1942 brought all recording activity in Singapore to a halt. The Japanese systematically looted the existing recording facilities and sent anything they thought useful back to Japan. No new records appeared in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation except a few issues on the Sun Record label that were not local recordings.

The post-war reconstruction period was necessarily initially focused on restoring essential services and on re-establishing the distribution of food and other goods. It was not until 1947–48 that new recordings began to appear and the record industry resumed normal operations. However, things rapidly returned to normal; by 1950, essentially the same practices and procedures as had existed in the pre-war period were back in use.

There were two factors that gradually resulted in some change. The first was the development of new tastes in local music. Malay kronchong was an established local style which had always been influenced by trends in Western music but had long existed in a standard form. During the 1930s, it began to incorporate elements of American swing18 and Latin-style songs, and in the 1940s and 1950s these influences increased. There were also many new recordings inspired by the “joget craze” that began in 1949.19

In Chinese music, new developments had also started before the war with the importation of “modern Chinese” music that had first developed in Shanghai during the 1930s. This was essentially a blend of Western jazz and popular songs with elements of traditional Chinese music to form a new style of Chinese pop music. The music was spread by the many recordings produced in Shanghai and Hong Kong on the New Moon and Pathe labels, which were soon available in Singapore. A contemporary newspaper report titled “Singapore band plays Chinese love songs in Western dance rhythm”20 describes the emerging popularity of this music. But the local record industry, dominated by EMI, was too conservative to take a chance on what was still a developing trend, and Chinese recordings made in pre-war Singapore continued to be largely traditional opera and dialect material.

When the Korean War began in 1950, the result was a sudden and dramatic increase in the need for raw materials including rubber, which led directly to the rubber boom of the early 1950s. Post-war austerity was suddenly replaced by a new prosperity, and the demand for records increased dramatically.21 Consequently, it was now economically viable for even a conservative record company like EMI to record new styles of music, and it launched several new series on Parlophone, His Master’s Voice and Regal in order to do so, all of which featured Chinese modern music recorded for the first time in Singapore.22

As a consequence, the pattern of local recording in Singapore which had been standard since the 1920s underwent some major changes. Previously, the major companies would conduct an annual recording session that might last a few weeks or months, during which a group of artists would record as many titles as possible, and these recordings would be released gradually over the following year before another recording session was held. In the 1950s, for the first time, the increased demand for new recordings meant that Hemsley and Co., the supervisors of local recordings for EMI, announced that “from now on there will be two recording sessions each year instead of one”.23

Other very significant changes soon followed. One was the introduction of microgroove vinyl records, which were first announced in Singapore in 1950.24 A gradual process began in which sales of the new vinyl discs increased until they eventually overtook the 78-rpm format in the late 1950s. The 78-rpm record was finally discontinued in 1960–61, with some labels continuing its use a little longer than others.

A second new development was the introduction of tape recording, which made the recording process much simpler and cheaper. The first reference I have found to the use of tape recording in Singapore is in 1951 in an article on the newly opened air-conditioned EMI recording studios in MacDonald House on Orchard Road,25 which mentions that “all recordings are made on the most modern… tape-recording apparatus”.26

With the most modern recording equipment and the only air-conditioned studios in Southeast Asia, Singapore continued to be a recording hub for the region. Performers from Malaya and Indonesia came to Singapore specifically to record. A press report mentions that many famous artists made recordings in Singapore, including “Rubiah, Momo, P. Ramlee, Asiah, Abdul Rahman, Julia and Lena, as well as many new discoveries”.27

The boom in record sales in the early 1950s also created opportunities for a number of smaller labels that filled niche markets. These included some pre-war labels that were revived such as Pagoda and Foo Ann, plus a host of new labels including Double Swallow (Teochew opera), Eastern (Hokkien pop), Flower Brand (Mandarin pop), Grand (Chinese and Malay pop), Horse Brand (Chinese pop), Piakay (Teochew opera), Tiger Brand (Chinese opera), and Unique (Mandarin modern Chinese songs).

When the Korean War ended in 1953, the rubber boom suddenly collapsed and record sales also suffered. The Parlophone and Regal series were discontinued and most of the new smaller labels also disappeared. However, the downturn was relatively brief.

A 1955 press report states that “the Singapore branch manager of The Gramophone Co. Ltd… said that… record sales have risen by leaps and bounds… and we have more than doubled last year’s turnover”.28 This is quite contrary to claims by Tan Sooi Beng that “by the 1950s advertisements of gramophone records in the local newspapers had almost disappeared” and that there was a “decline of the 78 rpm record industry in the 1950s”.29 Both these statements are incorrect. The brief crisis in 1954 when the rubber boom suddenly ended was only temporary and record sales were reported to have increased strongly only a year later.30 During 1957, sales only increased further.31

While it is true that in the late 1950s the sales of 78-rpm records were falling, this was not a general decline of the record industry as this decline was more than counterbalanced by increased sales of 45-rpm and LP vinyl records. Combined sales were actually increasing, and the changeover from the 78-rpm format to 45-rpm and LP discs was a normal development due to new types of records becoming available. In fact, in 1958 a new manufacturer of 78-rpm records was established in Singapore.32 This company initially pressed 78-rpm records from masters recorded in America that were issued on the Colortune and Coral labels. These were not local recordings, but it was the first company to manufacture records in Singapore, and to set up such a factory is hardly a sign that the record industry was in decline. Eventually, the Colortune and Coral labels were also produced as 45-rpm vinyl pressings, and by the early 1960s, the company began producing the Ruby label as 45-rpm and LP discs. All issues on Ruby were local recordings.

During the pre-war period, all records sold in Singapore were manufactured in Britain, Europe, India or Shanghai. Since the Ruby Record Co. was a relatively small operation, the importation of records manufactured elsewhere continued well into the late 1960s, when several larger record factories were established in Singapore. During the 1950s and most of the 1960s, the majority of records sold in Singapore were manufactured in India, Britain or Australia.

In the early 1960s, the record industry in Singapore was still dominated by EMI (as had been the case since the 1920s). The organisation was famously conservative when it came to signing up local talent in Asia, and the company probably saw no reason to go beyond the well-established forms of local popular music such as Malay kronchong and Chinese opera, which it had been recording for many years.

Despite the existence of a few small record companies in Singapore like Horse Brand and Ruby in the early 1960s, there was little significant competition for huge multinational companies like EMI as the minor labels restricted their activities to niche markets since they could not hope to compete with the resources available to EMI in terms of distribution and publicity.

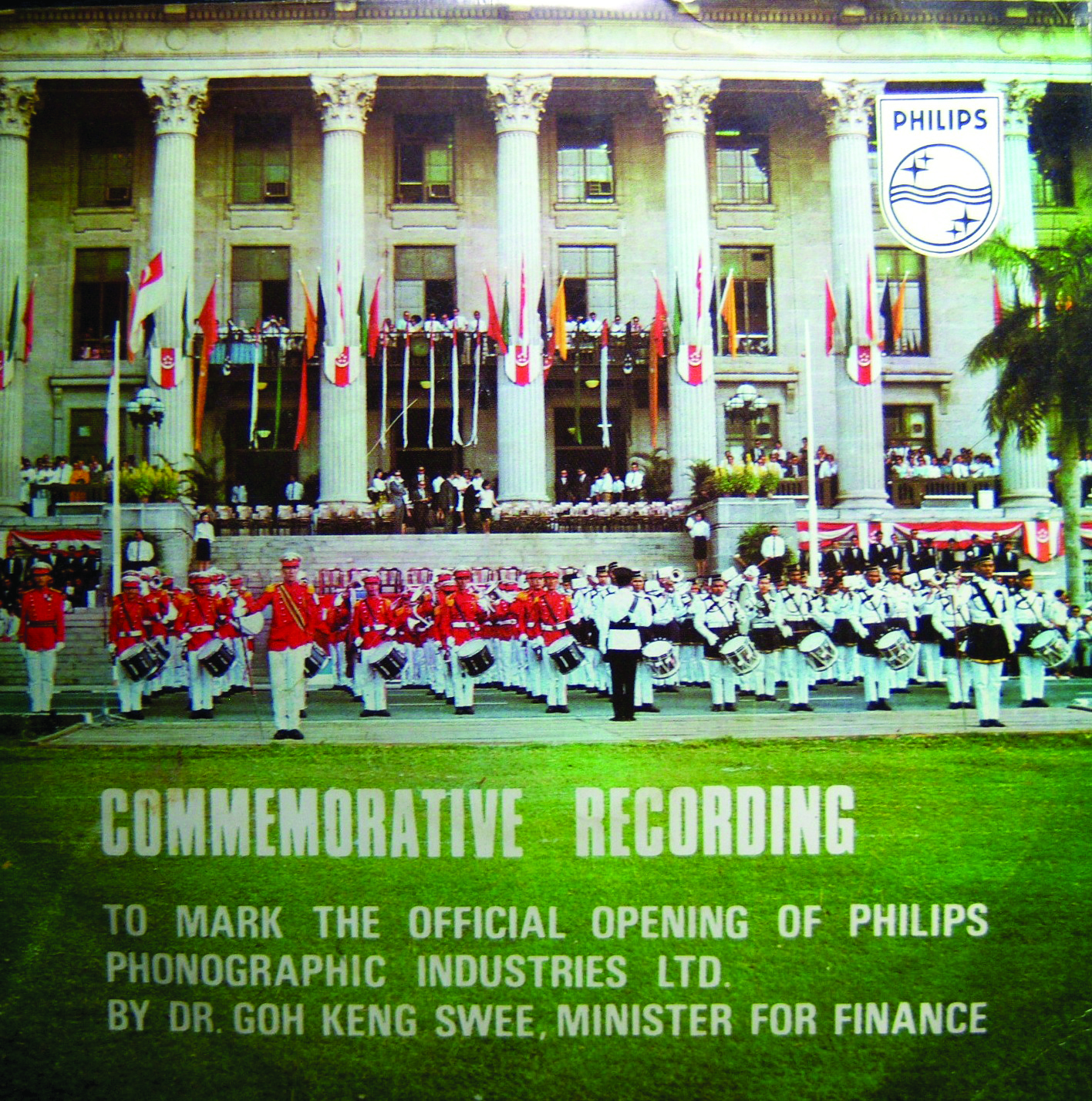

It was not until 1963 that a record company decided to release a record by a Singapore pop band. The company was Philips, and the record was by the band The Crescendos. Although it has been claimed that the 1961 concert in Singapore by Cliff Richard and The Shadows inspired the emergence of the local guitar-based pop bands that have become so well known as representative of 1960s Singapore music,33 it was really the phenomenal success of the first record by The Crescendos that led the industry to finally realise that recording local pop music had the potential to be a money-making venture.

By 1965, Philips had initiated a series of local releases that eventually resulted in a very fine catalogue of local pop releases over the next few years.34 Other labels were quick to follow suit, and soon several small local labels began actively recording a wide range of local popular music. Between 1965 and 1969, over 120 different labels released local recordings in Singapore. This figure did not include the long established EMI labels (Columbia, Pathe, Parlophone, Regal, Odeon, etc), or any of the numerous labels based in Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and elsewhere that were also distributed (and sometimes pressed) in Singapore, or the many British, European and US labels that released material recorded in those countries for the Singapore market.

Although it has been claimed that the 1961 concert in Singapore by Cliff Richard and The Shadows inspired the emergence of the local guitar-based pop bands that have become so well known as representative of 1960s Singapore music, it was really the phenomenal success of the first record by The Crescendos that led the industry to finally realise that recording local pop music had the potential to be a money-making venture.

In a single decade (1965–75), the Singapore record industry produced a huge range of recordings in a wide variety of styles. Local content included recordings in Chinese, Malay, English and other language groups ranging from traditional forms to the latest pop. The majority of recordings were in Malay or Chinese, with Mandarin and Cantonese accounting for most Chinese-language recordings, plus some in various dialects such as Teochew or Hokkien. There were also a significant number of English-language recordings, and many instrumental recordings (ranging from Western-style R&B to Chinese songs played in the current “A-Go-Go” style).

Apart from satisfying the local market, many companies exported a significant percentage of their production, especially to Malaysia and Indonesia. One relatively small producer, Kwan Sia Record Company, reported that half of the 8,000 copies pressed of a single LP release were exported to Indonesia at a value of about $30,000.35

By 1970, there were at least four disc manufacturers in Singapore – Unique Art Records Industrial Enterprise, Life Record Industries, Phonogram Far East and EMI (South East Asia) – all of whom pressed records on their own labels as well as for other companies. Exact figures are not available, but according to contemporary reports, record production at the four major pressing plants mentioned above reached one million discs per month.36

During the 1960s, Singapore bands frequently toured places like Sarawak, Brunei, Bangkok or Saigon, and bands from Indonesia, Malaysia, Sarawak, Brunei, the Philippines and other places in the region came to Singapore to appear at hotels and nightclubs or to use Singapore as a recording centre.37

By the early 1970s, the Singapore record industry had come a long way from the first primitive recordings made in 1903. Unfortunately, by the end of the 1960s, the local record industry had reached a peak, both in terms of creativity and in terms of production. While a significant number of records continued to be produced in the early 1970s, there was a gradual decline. The reasons are complex, but they included changes in technology, style and government policy. By the mid-1970s, Singapore was no longer as important a regional recording hub as it had been during the previous 75 years.

REFERENCES

Page 2 Advertisements Column 2: Chap Singa. (1937, January 8). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 2 Advertisements Column 3: Robinson & Co. (1892, May 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 2 Advertisements Column 1: John Little & Co., Ltd – The gramophone. (1899, August 29). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 4 Advertisements Column 4: Chap Kuching. (1934, July 11). The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 5 Advertisements Column 1: His Master’s voice studio. (1951, January 10). Singapore Standard, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 17 Advertisements Column 3. (1938, November 11). The Malaya Tribune, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Page 16 Advertisements Column 3: Canary. (1939, March 10). The Malaya Tribune, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Felix. (1951, May 2). Boom in sale of Malay records. The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

First colony record factory. (1958, May 27). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

First [Modern] Hokkien records made. (1950, June 18). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Great’ demand for Malay star records. (1951, May 25). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gronow, P. (1981, May). The recording industry comes to the Orient. Ethnomusicology, 25 (2), 251–284. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Happiness is a pop star called Miss Vivi. (1969, October 25). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kartini, S. (2008, April). Edwin Arthur Brown’s musical contribution to Singapore. BiblioAsia, 4 (1), 40–44. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website.

Ken Jalleh. (1949, October 2). Modern joget is here to stay. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Laird, R. (1999). Sound beginnings: The early record industry in Australia. Sydney: Currency Press. (Call no.: RBUS 338.476213893 LAI)

Local choirs – Successful recording of choruses . (1932, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Local gramophone records for the teaching of English. (1936, August). Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teachers’ Association, 2, 33.

Local-made ‘pop’ records go to Indonesia. (1968, May 24). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

L.P. records - First impressions. (1950, September 20). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Malay music goes swing. (1950, March 19). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Malayan disc sales show 25 per cent rise. (1958, February 14). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Marker, H.L. (1913). Returns from record making trip around the world. Talking Machine World, 9 (1), 43–44.

Pereira, J.F. (1999). Legends of the Golden Venus. Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING q781.64095957 PER)

Records firm opening. (1967, November 18). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Recording session now in progress. (1951, July 6). Singapore Standard, p. 10.

Singapore band plays Chinese love songs in Western dance rhythm. (1936, July 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore’s recording firms hit happy note. (1970, May 11). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Switch on – 500,000th record by Dr Goh. (1967, November 20). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tan, S.B. (1996, Autumn–1997, Winter). The 78rpm record industry in Malaya prior to World War II. Asian Music, 28 (1), 1–41, p. 34. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

“The Music Goes Round” in J. N Moore. (1999). Sound revolutions: A biography of Fred Gaisberg, founding father of commercial sound recording. London: Sanctuary Publishing. (Call no.: 780.266092 MOO [ART])

The phonograph. (1892, May 10). Straits Times Weekly, p. 274. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Turnover doubled. (1955, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Untitled. (1892, May 16). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 8.

Untitled. (1929, March 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wee, L. (1970, May 11). Singapore’s recording firms hit happy note. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

The first study of early record industry activity in Asia to be published was a broad overview by Gronow, P. (May 1981). The recording industry comes to the Orient. Society for Ethnomusicology, 25(2), 251–284. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. It contains very useful background information and some interesting statistical data, but only mentions Singapore briefly as the coverage is quite broad (it includes India, China, Japan and other regions outside Southeast Asia). The only significant study of record industry history in Southeast Asia is Tan, S. B. (Autumn 1996–Winter 1997). The 78rpm record industry in Malaya prior to World War II. Asian Music, 28(1), 34. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. As the title indicates, this is a brief history of the record industry from a Malaysian perspective and only covers the period up to 1942. It includes a very useful summary of the statistical data from Gronow’s article, but is not comprehensive and includes some errors of fact and false assumptions as the author is a musicologist, not a record industry historian. ↩

-

Straits Times Overland Journal, 16 May 1892, p. 8. ↩

-

Straits Times Weekly, 10 May 1892, p. 274. ↩

-

Laird, R. (1999). Sound beginnings: The early record industry in Australia (pp. 3–9). Sydney: Currency Press. ↩

-

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884- 1942), 16 May 1892, p. 2. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 29 Aug 1899, p. 2. ↩

-

The Fred Gaisberg diaries were published as The Music Goes Round (New York, Macmillan, 1942) and extracts are available in Moore, J. N (1999). Sound revolutions: A biography of Fred Gaisberg, founding father of commercial sound recording. London: Sanctuary Publishing. ↩

-

This procedure is misunderstood in Tan’s study as she claims that “recording engineers such as Gaisberg often stopped by Penang” (p. 3) and she refers to “the recordings made by Gaisberg in Penang” (p. 6) when no such recordings were made. Gaisberg’s diaries show that he did not record in Penang. I believe this mistake is due to a misunderstanding of the fact that Penang is shown on the labels of some of these Gaisberg 1903 recordings. In the early days of the record industry it was a common practice to show on the label the place from which the recording artist originated, but this did not necessarily mean that the recordings were made in that location. Early recording equipment was heavy, cumbersome and difficult to transport so it was simply not possible to travel around making recordings along the way. Instead, artists from various cities or towns would travel to a nearby regional centre and all recordings would be made in the same location. ↩

-

Marker, H. L. (1913). Returns from record making trip around the world. Talking Machine World, 9(1), 43—44. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 13 Mar 1929, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 6 May 1932, p. 12. ↩

-

For a detailed study of E.A. Brown’s extensive musical career in Singapore see Kartini, S. (2008). Edwin Arthur Brown’s musical contribution to Singapore. BiblioAsia, 4 (1), 40–44. But this excellent article makes no mention of his recordings. ↩

-

Local gramophone records for the teaching of English. (1936, August). Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teachers’ Association, 2, p. 33. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 11 Jul 1934, p. 4. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 8 Jan 1937, p. 8. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 11 Nov 1938, p. 11. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 10 Mar 1939, p. 16. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Mar 1950, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 2 Oct 1949, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Jul 1936, p. 4. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 25 May 1951, p. 4. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 18 Jun 1950, p. 5. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 2 May 1951, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 20 Sep 1950, p. 6. ↩

-

The EMI recording studios at MacDonald House opened in January 1951. Singapore Standard, 10 Jan 1951, p. 5. ↩

-

Singapore Standard, 6 Jul 1951, p. 10. ↩

-

Singapore Standard, 6 Jul 1951, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Dec 1955, p. 10. ↩

-

Tan, S. B. (1997). The 78rpm record industry in Malaya prior to World War II. Asian Music, 28(1), 34. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 15 Dec 1955, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 14 Feb 1958, p. 14. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 May 1958, p. 12. ↩

-

See Pereira, J. F. (1999). Legends of the Golden Venus. Singapore: Times Editions. The tendency by writers about popular music to seize on a single event (such as the 1961 Cliff Richard concerts) to explain the development of modern pop music in 1960s Singapore is to present mythology as fact. Despite Pereira’s claim about the absence of guitar bands in Singapore prior to 1961, the reality is that there were many such bands but the conservative policies of the local record companies meant that they never recorded, so they have tended to be forgotten. Obviously a local musical tradition can only develop over time, and is not caused by any single event. By understanding how the Singapore record industry operated we can better discern how local musical culture evolved, even if in some cases there are no recordings of some crucial genres or periods. ↩

-

Philips was the first multinational record company to establish a record-pressing plant in Singapore. It was officially opened on 24 November 1967, but by then had already produced more than half a million records. The Straits Times, 18 Nov 1967, p. 13. Forty percent of the factory’s production was exported to Indonesia, Hong Kong, Thailand, Ceylon and Malaysia. The Straits Times, 20 Nov 1967, p. 16. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 May 1968, p. 14. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 11 May 1970, p. 10. ↩

-

To give just one example, it was reported in 1969 that a group of 30 Indonesian singers had come to Singapore to record at Kinetex Studios. The artists included Vivi Sumanti, Bing Slamet and Tanti Josepha, and they intended to record “250 songs in Malay, Indonesian, Chinese, English and several European languages”. The group of artists were to stay for three months, recording almost every day during that period, and “cutting over 70 EPs and 25 LPs”. The Straits Times, 25 Oct 1969, p. 8. ↩