Illustrating the Future: Southeast Asian Ceramic Special Exhibition Catalogues, 1970–2009

Exhibition catalogues are important guidebooks for ceramic enthusiasts and researchers to understand Southeast Asian ceramics. Compared with words, images in exhibition catalogues can provide a visual representation and perceptual knowledge of the styles and forms of ceramics.

Exhibition catalogues are long-lasting records and sources of references on ceramic exhibits shown for specific purposes in museums so as to affect the audience in a predetermined direction. Therefore, it is one of the best tools for us to review the history of research into and future trends of Southeast Asian ceramic studies.

“Southeast Asian ceramics” emerged as an independent analytical unit after World War II, when Southeast Asia became a region with clear political boundaries. The study of important long-term inter-regional cultural and technological interactions has suffered through the creation of modern political barriers. Chinese ceramic traditions are one of the major elements in the development of ceramic industries in Southeast Asia. The timeframe of this article begins with the 9th century, when Chinese trade ceramics were first imported into Southeast Asia, and ends in the 16th century, the period when Southeast Asian polities began to come under the political control of European empires.

This article traces the history of Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibition catalogues from the 1970s, a decade when most of the existing Southeast Asian ceramic societies were established in the region and many exhibition catalogues were published, to the re-emergence of such exhibitions in the late 2000s.1 Unlike permanent exhibitions, special exhibitions pay particular attention to a group of ceramic exhibits that are brought together for public display. They also offer the opportunity for viewers to observe and compare ceramics from different parts of Southeast Asia conveniently concentrated in one place for a limited period of time. Additionally, they can enhance the popularity and professional reputation of the museum by highlighting and promoting several new discoveries or important ceramic pieces. Although permanent exhibitions represent long-term results based on the hard work done by museum staff over many years of collecting, preserving and researching, most of the exhibition catalogues depict short-term and temporary special exhibitions instead of permanent exhibitions in the museum.2 As Southeast Asian ceramic exhibition catalogues are the main publications for special exhibitions in museums, these form the main focus of this study.

Some Observations on the Exhibition Catalogue

Most of the exhibition catalogues surveyed in this paper were obtained from libraries in Singapore. Singapore has a unique geographical and historical position in Southeast Asian ceramic studies, and is considered a hub of scholarly publications and landmark exhibition catalogues on Southeast Asian ceramic topics in the region.3 The catalogues studied were from the Singapore and Southeast Asian collection, art and history collections and Ya Yin Kwan Collection of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library of Singapore. In addition, libraries at the National University of Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies and the Asian Civilisations Museum hold a number of Southeast Asian, Chinese and Japanese ceramic exhibition catalogues that were published in various parts of the world.

Twenty-three special exhibition catalogues on Southeast Asian ceramic topics were selected from major Singapore library collections. The selection criteria were based on whether the catalogue was a special exhibition catalogue, whether the major topic of the exhibition catalogue was connected with Southeast Asian ceramics, and whether it was available in major Singapore library collections. Many important exhibition catalogues, drawn from a much wider range of pioneer scholars or institutions outside of Singapore collections or books written in local languages, should be acknowledged.4 We hope that this general overview will provide an indication of the future trends of exhibitions on Southeast Asian ceramic studies.

Five aspects of general information from the special exhibition catalogues will be observed: the quantity of ceramic exhibits by countries; sources of the exhibits; Southeast Asian ware type (glazed, unglazed stoneware or earthenware); the venues, dates, and host organisations and countries; and the topics of associated essays as well as the number of essays.

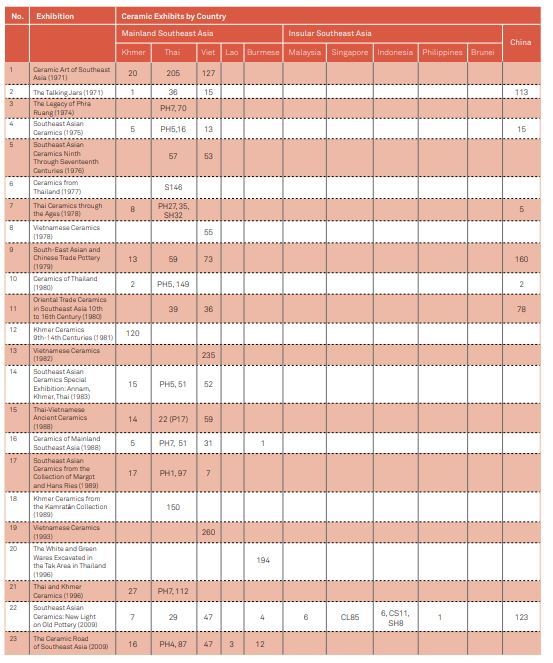

Quantity of Ceramic Exhibits by Countries

With regard to the quantity of ceramic exhibits by countries, Thai and Vietnamese ceramic exhibits are found in much higher proportion than any other Southeast Asian ceramics. Thai and Vietnamese ceramics are usually considered as the only theme in the exhibition. Examples of Thai ceramic exhibitions include The Legacy of Phra Ruang (1974), Ceramics from Thailand (1977), Thai Ceramics through the Ages (1978) and Vietnamese ceramic exhibitions held in 1978, 1982 and 1993. Khmer ceramics make up the third-largest category of ceramic exhibits. Its thematic exhibition includes Khmer Ceramics 9th to 14th Centuries (1981) and Khmer Ceramics from the Kamratān Collection (1989). Very few exhibition catalogues deal with Burmese and Lao ceramics. The White and Green Wares Excavated in the Tak Area in Thailand (1996) is an exceptional case. About 194 pieces of white-glazed Burmese ware with green decoration, obtained from illegal excavation along the Thai-Myanmar border in the Tak area of Thailand near the Mae Sot mountain region, were first introduced in a special exhibition in the Machida City Museum.5 Aside from this special exhibition, ceramics produced in Myanmar or Laos and insular Southeast Asian countries, for instance, Brunei, have seldom appeared in Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibitions. These phenomena may reflect a strong contrast in the development of Southeast Asian ceramic studies, and the perceptions of collectors (or lenders) and organisers on which kind of Southeast Asian ceramics should be included in the exhibition.

Another typical example is whether Chinese ceramics are present in Southeast Asian ceramic exhibitions. In Table 1, 7 out of 23 exhibitions present Chinese ceramics. In the Talking Jars (1971), South-East Asian and Chinese Trade Pottery (1979) and Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009), more than 100 Chinese pieces were shown. Another exhibition, Oriental Trade Ceramics in Southeast Asia 10th to 16th Century (1980), also displayed 78 pieces of Chinese ceramics. Chinese ceramics are covered in the Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibitions if the organisers support the concept that the flourishing of trade between China and Southeast Asia would transmit new elements to Southeast Asian ceramic products and their societies, and Chinese ceramics could provide one of the major elements in the development of ceramic industries in Southeast Asia. However, if Southeast Asian ceramic traditions, cultural identity and internal unity are emphasised, Chinese ceramics would be excluded from the exhibitions. Table 1 indicates that the latter approach is more frequent.

Source of the Exhibits

Many ceramic exhibits from Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibitions were lent by private collectors or museums. Singapore is an ideal location to display such pieces since local museums and institutes and members of the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society (SEACS) always provide vital support and act as sources of exhibits, such as for the Ceramic Art of Southeast Asia (1971), Khmer Ceramics 9th to 14th Centuries (1981) and Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009) exhibitions.6 Another supportive country is Japan. Many masterpieces in excellent condition were meticulously selected from institutions such as the Tokyo National Museum, Idemitsu Museum of Art, Machida City Museum, Southeast Asian Ceramics Museum, Kyoto, and Fukuoka Art Museum, or from collections held by private collectors such as Hiroshi Fujiwara and Hiromu Honda. These pieces were displayed in various special exhibitions such as Thai-Vietnamese Ancient Ceramics (1988), Khmer Ceramics from the Kamratān Collection (1989) and Vietnamese Ceramics (1993). Margot and Hans Ries were two of the pioneer collectors of Southeast Asian ceramics. After moving to Los Angeles in the early 1950s, they donated most of their collections of Southeast Asian ceramics to the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California.7 Another famous collection is the Hauge family’s gift of Khmer ceramics to the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution.8

Some exhibits were purchased by the museums or borrowed from other galleries and museums in different countries. For instance, for the special exhibition Southeast Asian Ceramics Ninth through Seventeenth Centuries (1976), the organising team led by Dean Frasché successfully grouped ceramic exhibits from the US, Belgium, Netherlands, Japan, Thailand and Indonesia that were brought together for visitors to make comparisons among ceramics conveniently in one place. However, cooperative special exhibitions with archaeological departments in Southeast Asia have been very rare. One example is Thai Ceramics through the Ages (1977), launched by The Urban Council of Hong Kong and the Fine Arts Department, Thailand. Only a small proportion of archaeological finds with clear provenances and dating information was chosen for display, including the ceramic discoveries from both land-based and underwater archaeology. Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009) gave an extraordinary demonstration. As compared with previous special exhibitions, this exhibition paid more attention to shipwreck ceramics. They were highlighted with serious research on the relationships of ceramic trade within the region and between China and Southeast Asia.9

Southeast Asian Ware Type (Glazed, Unglazed Stoneware or Earthenware)

Southeast Asian ceramic ware types from the 4th to 16th centuries make up the largest ceramic ware category in the special exhibitions. This result parallels the increased momentum of Southeast Asian ceramic exports. In particular, the development of Vietnamese and Thai ceramic production during the period of distribution of Chinese ceramic export wares was limited during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE).10 By comparison, ceramic ware produced from the 9th to 13th centuries, a period when glazed ceramics were first produced in Southeast Asia, falls in the second group.

In general, Southeast Asian ware type can also be classified into glazed stoneware, unglazed stoneware and earthenware. Most exhibits from this pre-modern period are intact glazed stoneware from Vietnam, Cambodia and Northeast Thailand. This is because the intense debate about the origins of Southeast Asian glazed stoneware in Southeast Asian ceramic study circles was closely linked to the beginning of China’s systematic export trade in ceramics from the 9th century. However, earthenware is an important Southeast Asian ceramic ware type. Except for Ban Chiang earthenware from Thailand, earthenware has never played a major role in ceramic exhibitions. About 10 out of 23 exhibitions include Ban Chiang ware. This reflects the idea (since challenged) that Ban Chiang earthenware was a distinctive artistic and technological ceramic tradition that could be traced back 4,000 years in Southeast Asia as the result of significant excavations at the Bronze and Iron Age site of Ban Chiang from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.11 However, there is still very little in-depth research and display of both mainland and island Southeast Asian earthenware from the pre-modern period in special exhibitions.

In addition, only a few special exhibitions have displayed important research resources for Southeast Asian ceramic studies: kiln wasters and ceramic fragments, the key materials for the study of technologies and craftsmanship of Southeast Asian ceramic production.

Venue, Date and the Host Organisation and Country

Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibitions were often scheduled for a limited period of time. In general, the exhibitions did not last longer than three months. For instance, The Legacy of Phra Ruang (1974) exhibits for sale in London were only displayed for 15 days. The longest special exhibition, Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009), was held at the National University of Singapore Museums (NUS Museums) over nine months and 22 days. The Oriental Trade Ceramics in Southeast Asia 10th to 16th Century (1980) catalogue was produced to accompany the travelling special exhibition for three months from the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (6 June–20 July 1980) to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (1–31 August 1980), and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (4 October–9 November 1980). A similar practice can be seen in shipwreck ceramic exhibitions for public education or auction purposes in recent years.12

Many ceramic exhibitions were held in art museums or art galleries. This observation demonstrates that Southeast Asian ceramics were treated as art objects or part of art collections rather than archaeological or historical resources. The major organisers were the founding persons or the successors of the art or ceramic societies or the museums with that area of ceramic collections and specialisation, such as SEACS, which was established in Singapore in 1969. The first Southeast Asian ceramic exhibition, entitled Ceramic Art of Southeast Asia, organised by the first SEACS president, William Willetts, was held in 1971 at the Art Museum in the University of Singapore (SEACS 1971).

Topic of Associated Essays and Number of Essays

The typical exhibition catalogue includes at least one essay. That essay is always an introductory essay about the ceramic exhibits written by the organisers or renowned ceramic specialists in the field. Some catalogues compile three to four excellent articles with serious studies on various topics, like the relationship between Chinese and Southeast Asian ceramics, or ceramic traditions, as well as the biographies of the collectors. Oriental Trade Ceramics in Southeast Asia 10th to 16th Century (1980), Khmer Ceramics 9th to 14th Century (1981), Vietnamese Ceramics (1982) and Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009) are some of the most exemplary works. These essays, containing detailed illustrations of ceramic exhibits, are extremely important in transmitting knowledge to succeeding scholars of the field.

Table 1: The Quantity of Ceramic Exhibits by Country13

LEGEND

CL: Chinese ceramics land-based excavation

SH: shipwreck

CS: Chinese ceramics shipwrecks

PH: pre-history

Visits to Southeast Asian Ceramic Exhibitions in Singapore and Taiwan

To present a better understanding of the future study of Southeast Asian ceramics, I want to discuss two Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibitions held in Asia in recent years. The first is the special exhibition, The Ceramic Road of Southeast Asia: Pottery Villages, Ancient and Contemporary Ceramics, which was staged from 17 October 2009 to 28 February 2010 in Taipei County Yingge Ceramics Museum, Taiwan, one of the most well-known ceramic museums in Asia. About 240 ceramic works were included in the exhibition. The objective of this exhibition was to “provide the Taiwanese [with] a deeper understanding of Southeast Asia and better appreciation to their Southeast Asian neighbours”.14

The Southeast Asian artefacts joined collections through a variety of routes: through private collections on loan from different museums and institutes from Japan, Taiwan and Thailand or archaeological discoveries in Taiwan. I was very impressed that some selected pieces were exhibited on a large and low platform with glass frames but not much protection. Such a display would be refreshing to visitors because the ceramic objects were spread over a rather wide expanse, resulting in blank spaces. Visitors could experience a greater connection with the seemingly unprotected ceramic objects, while the glass frames served to remind visitors that although Southeast Asian ceramics are cheap and common enough compared to gold ornaments or paintings, they were still untouchable art objects. We should note also that this special exhibition adopted the “handle holes” display method from the Southeast Asian Ceramic Museum, Bangkok, and allowed visitors to touch wasters.15

This exhibition was apparently intended to showcase certain kinds of Southeast Asian ceramic exhibits: intact, exceptional, exquisite, exotic, glazed and preferably high-quality vessels mainly from private collections in the museums, with approximated dating, provenance and places of discovery. Unlike most previous special exhibitions, The Ceramic Road of Southeast Asia was surprisingly concerned with ceramics from mainland Southeast Asian countries (including Laos and Myanmar), both ancient and contemporary ceramic works, the significance of ceramic traditions, and a study on pottery villages and usage of the ceramic vessels (see Table 1). Undoubtedly it would yield a broader view and generate comparatively greater interest in Southeast Asian ceramics among researchers and ceramic enthusiasts.

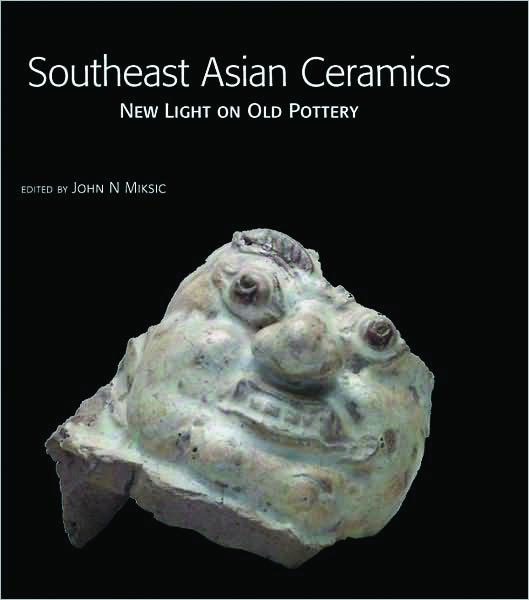

Another special exhibition, Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, organised by SEACS and NUS Museums, was displayed from 14 November 2009 to 5 September 2010 at NUS Museums. Since its establishment in 1969, SEACS has played an important role in the development of Southeast Asian ceramic studies and the transmission of the accomplishments of Southeast Asian ceramic researchers. In 1971, its pioneering exhibition catalogue “Ceramic Art of Southeast Asia: First Annual Exhibition” was published. The special exhibition 38 years later marked the 40th anniversary of SEACS16 and paid tribute to the late Dr Roxanna Brown.17

Compared with the Taiwan exhibition, some ceramic exhibits were protected within three-tiered glass vitrines. These fit well in the limited exhibition space and directed visitors’ attention in particular to the ceramic objects in the upper and middle layer. The interpretive labels in front of the exhibits and stories about the discoveries on the floor panels showed that the ceramic objects were unified as a group based on the consistency of content and the kinds of materials.

The exhibition focused not only on ceramic findings from mainland Southeast Asian kiln sites, but also on the fragmented, general, coarse unglazed stoneware and earthenware, tiles and brick building materials with archaeological contexts from both insular and mainland Southeast Asia. Traditionally, an intact and fine piece is selected as the major image on the front cover of an exhibition catalogue. However, in Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, the editor made the bold choice of a ceramic fragment of a glazed milky-blue Sawankhalok guardian figure for the front cover. This shows that fragments were considered an important component in this exhibition.18 The essays in the exhibition catalogue provided many substantial research findings and new ideas on Southeast Asian ceramic studies, including kilns of Southeast Asia, research on ceramic trade within Southeast Asia and between Southeast Asia and China.19

Apparently, both exhibition organisers indicated their interest in the hot topic of the revival, protection and promotion of Southeast Asian ceramics. The Ceramic Road of Southeast Asia organisers intended to raise awareness of the connection between contemporary and ancient Southeast Asian ceramics. For instance, the editors separated the special exhibition catalogue into two volumes: all contemporary ceramic artworks by artists in Southeast Asia were grouped in volume one, while the ancient ceramic exhibits and related essays were compiled in volume two. They also used Singaporean ceramist Swee Tuan Pang’s artwork “Ripples” to represent the ceramic road of Southeast Asia embraced by the intriguing changeable and unpredictable nature of water, and put a Si Satchanalai celadon Kinnariewer at the bottom-right corner of the front cover.20 The catalogue included the study of contemporary earthenware production in various pottery villages in Southeast Asia. The contemporary earthenware traditions may provide the essential link with past technologies of Southeast Asian ceramic production. In Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, the curators displayed the archaeology-inspired pots of Ng Eng Teng, the grandfather of Singapore sculpture, together with the ancient potteries in the exhibition.21 Another possible method of making the connection between contemporary and ancient ceramics is to produce replicas of ancient ceramics to help revitalise Southeast Asian ceramic production. In the meantime, it is possible to use different approaches to integrate both contemporary and ancient Southeast Asian ceramics in the same exhibition. It also indicates that systematic analysis of the link between contemporary and ancient Southeast Asian ceramics and collaboration between contemporary ceramic artists, art historians and archaeologists within the region will further increase in the near future.

Discussion

As an object-oriented display, a Southeast Asian ceramic special exhibition is more heavily reliant on ceramic objects that form the foundation of our understanding of ceramics than on any other form of interpretive media. However, ceramic exhibitions are always lacking in dynamic and participatory elements.22 Is it necessary to put a protective glass front on all ceramic exhibits, thus making them untouchable art objects? Some exhibits, such as heirloom jars, kiln wasters, ceramic fragments of recent date, and contemporary earthenware are common pottery types that can be found in tribal houses, ceramic workshops or elsewhere. They are essential components of Southeast Asian ceramic studies and should not be treated as rare, precious, individual and unusual pieces in exhibitions. As the eminent French archaeologist and Southeast Asian ceramic scholar Bernard P. Groslier pointed out, “The amateurs (the hunters of rare and precious objects) risk selecting only ‘exceptional’ pieces, and end up with only a partial and prejudiced view of this (Southeast Asian ceramic) art… [I]n 1981, due to the absence of systematic studies, identification and dating are frequently done ‘negatively’ by ‘impressionist’ comparisons… it will be dated by ‘likeness’ to some pieces seen through the glass of a museum showcase or during a visit to a colleague or in a sales catalogue.”23 Thirty years later, as more archaeological data has been accumulated and more in-depth and comprehensive studies have been done by researchers, this unbalanced situation has improved.

What are the future trends in Southeast Asian ceramic studies? Based on the above analysis, topics on archaeological ceramic findings, shipwreck ceramics in the region, the links between contemporary and ancient Southeast Asian ceramics, and comparisons between Southeast Asian and Chinese ceramics will become more significant in future studies. Moreover, special exhibitions organised by various organisations from different countries, displaying cross-border Southeast Asian ceramic findings with proper dating and provenance information for comparison, and accompanied by exhibition catalogues containing several substantial essays and informative illustrations of ceramic exhibits will not only be a dream. The distinctive characters of Southeast Asian ceramic traditions – unity and diversity – will then emerge in their fullness through exhibitions and their catalogues.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Louise Allison Cort, Curator for Ceramics, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and Associate Professor John N. Miksic, Southeast Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore, in reviewing the paper.

REFERENCES

Belcher, M. (1991). Exhibitions in museums. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

Bluett and Sons, Ltd. (1974). The legacy of Phra Ruang: An exhibition of Thai ceramics and of ancient pottery from Ban Chieng. London: Bluett and Sons, Ltd.

Brown, R.M. (1989). Guangdong: A missing link to Southeast Asia (pp. 81–85). In R.M. Brown (Ed.), Guangdong ceramics from Butuan and other Philippine sites. Manila: Oriental Ceramic Society of the Philippines. (Call no.: RART q738.074599 GUA)

Brown, R.M. (2004, September). Book review: Ceramics from the Thai-Burma border. Southeast Asian Ceramics Museum Newsletter, 1 (1), 2.

Brown, R.M. (2009). Southeast Asian ceramics museum, Bangkok University. Bangkok: Bangkok University Press.

Brown, R.M. (2009). The Ming gap and shipwreck ceramics in Southeast Asia: Towards a chronology of Thai trade ware. Bangkok: The Siam Society. (Call no.: RSEA 738.09593 BRO)

Chen, T.H. (2009). Recognizing Southeast Asia. In M-L. Hsieh (Ed.), The ceramic road of Southeast Asia: Pottery villages, ancient and contemporary ceramics II. Taipei: Taipei County Yingge Ceramics Museum.

Chia, A. (2009). Preface. In J.N. Miskic (Ed.), Southeast Asian ceramics: New light on old pottery. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. (Call no.: RSING 738.09595 SOU)

Cort, L.A., Farhad, M. & Gunter, A.C. (2000). Asian traditions in clay: The Hague gifts. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Dofflemyer, V. (1989). Southeast Asian ceramics from the collection of Margot and Hans Ries. Pasadena: Paciific Asia Museum. (Call no.: RSEA 738.309593074 DOF)

Drzik, A.M. (1983). Southeast Asian ceramics from the collection of Mr & Mrs Andrew M.Drzik. Tokyo: A.M. Drzik. (Call no.: RSING 738.0959 DRZ)

Frasche, D.F. (1976). Southeast Asian ceramics: Ninth through seventeenth centuries. New York: The Asia Society. (Call no.: RSEA 738.0959 FRA)

Fujiwara, H. (1990). Khmer ceramics from the Kamratåaçn collection in the Southeast Asian Ceramics Museum, Kyoto. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 738.30959607452 FUJ)

Groslier, B.P. (1981). Introduction to the ceramic wares of Angkor (pp. 9–40). In D. Stock (Ed.), Khmer ceramics 9th–14th century. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. Retrieved from BookSG.

Guy, J. (1980). Oriental trade ceramics in Southeast Asia, 10th to 16th century: Selected from Australian collections, including the Art Gallery of South Australia and the Bodor collection. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria. (Call no.: RSING 738.0959 GUY)

Guy, J., & Stevenson, J. (Eds.). (1997). Vietnamese ceramics: A separate tradition. Chicago, IL: Art Media Resources with Avery Press.

Hsieh, M.L. (Ed.). (2009). The ceramic road of Southeast Asia: Pottery villages, ancient and contemporary ceramics I. Taipei: Taipei County Yingge Ceramics Museum.

Machida City Museum. (1993). Vietnamese ceramics. Machida: Machida City Museum.

Machida City Museum. (1996). The white and green wares excavated in the Tak area in Thailand. Machida: Machida City Museum.

Miskic, J.N. (Ed.). (2009). Southeast Asian ceramics: New light on old pottery. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. (Call no.: RSING 738.0959 SOU)

Moes, R. (1975). Southeast Asian ceramics. New York: Brooklyn Museum. (Call no.: RUR RSEA 738.0959074 MOE)

Musee Royal de Mariemont. (1978). Ceramiques Vietnamiennes : Musée Royal de Mariemout, 28 Avril-15 September 1978. Mariemout, Belgium: Musee Royal de Mariemout. (Call no.: RUR RSEA 738.09597074 CER)

Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong. (1979). South-East Asian and Chinese trade pottery: An exhibition catalogue. Hong Kong: The Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong. (Call no.: RSEA 738.20959 ORI)

Ozaki, N. (Ed.). (1996). Thai and Khmer ceramics. Fukuoka: The Fukuoka Art Museum. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Peacock, B. A. V. (1978). Thai ceramics through the ages. Hong Kong: Urban Council. (Call no.: RSEA 738.09593 THA)

Richards, D. (Ed.). (2003). Lost for 500 years: Sunken treasures of Brunei Darussalam. Sydney: Art Exhibitions Australia Limited. (Call no.: RSEA q910.95955 LOS)

Sabapathy, T.K. (Ed.). (2002). Past-present: A history of the University Art Museum. In Past, present, beyond re-nascence of an art collection. Singapore: National University of Singapore Museums. (Call no.: RSING q709.5 PAS)

Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. (1971). Ceramic art of Southeast Asia: First annual exhibition. Singapore: Art Museum, University of Singapore. Retrieved from BookSG.

Stanford University Museum of Art. (1980). Ceramics of Thailand. Stanford: Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. (Call no.: RSEA 738.09593 CER)

Stock, D. (Ed.). (1981). Khmer ceramics 9th–14th century. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. Retrieved from BookSG.

The Museum Yamato Bunkakan. (1983). Southeast Asian ceramics special exhibition: Annam, Khmer, Thai. Nara: The Museum Yamato Bunkakan.

The Shoto Museum of Art. (1993). Thai-Vietnamese ancient ceramics. Tokyo: The Shoto Museum of Art.

Till, B. (1988). Ceramics of mainland Southeast Asia. Victoria, B.C.: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. (Call no.: RSEA 738.30959 TIL)

Tokyo National Museum. (2000). Korean and other Asian ceramics excavated in Japan. Tokyo: Tokyo National Museum.

Ubersee-Museums und Celadon Co. Ltd. (1977). Keramik aus Thailand: Sukhothai & Sawankhalok. Kuala Lupur: Ubersee-Museums und Celadon Co. Ltd. (Call no.: RUR RSEA 738.3095930740352 KER)

Vancouver Society for Asian Art. (1971). The Vancouver Society for Asian Art presents The talking jars: An exhibition of oriental ceramic folkwares found in South East Asia, Centennial Museum, Vancouver, Canada, October-November, 1971. Vancouver: Vancouver Society for Asian Art. (Call no.: RSEA 738.095074 VAN)

White, J.C. (1982). Ban Chiang: Discovery of a lost bronze age: An exhibition organised by the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, the Smithsonian Institution, Traveling Exhibition Service, the National Museums Division, Department of Fine Arts, Thailand. [Philadelphia]: The Museum. (Call no.: RSEA 959.302074 WHI)

Wong, W.Y. (2009, September–December). A glimpse at Southeast Asian ceramics publications on Southeast Asian ceramics since the 1960s. SPAFA Journal, 19 (3), 5–17.

Yamazaki, K. (1996). Study on the material and technique of white-glazed ware with green decoration. In H. Gakuji & K. Yamazaki. (1996). The white and green wares excavated in the Tak area in Thailand. Tokyo: Machida City Museum.

Young, C.M., Dupoizat, M.F. & Lane, E.W. (Eds.). (1982). Vietnamese ceramics: With an illustrated catalogue of the exhibition organised by the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society and held at the National Museum, Singapore in June 1982. Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society. (Call no.: RSING 738.09597 VIE)

NOTES

-

For example, see Guy & Stevenson, 1997 ↩

-

Yamazaki, 1996, p. 137. About Burmese ceramics from the Thai-Burma border, see Roxanna Brown’s book review, Sep 2004, p. 2. ↩

-

Some Southeast Asian ceramic exhibits were from the Art Museum of University of Singapore. See Sabapathy 2002, pp. 16–19. ↩

-

Dofflemyer, 1989, pp. vi–ix. ↩

-

See Cort, et al. 2000, “Foreword” by Milo Cleveland Beach, Director, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, pp. 6–7. ↩

-

The travelling exhibition on Sunken Treasures of Brunei Darussalam from 2003 to 2005 in Australia is an example. See Richards, 2003. ↩

-

The Quantity of Ceramic Exhibits by Countries was based on the pre-modern ceramic exhibits mentioned in the exhibition catalogue. It may not include all the exhibits shown in the exhibition. ↩

-

Chen, 2009, p. 15. ↩

-

Brown, 2009, pp. 60–61. ↩

-

In 1993, the Tokyo National Museum held a special exhibition entitled Korean and Other Asian Ceramics Excavated in Japan (one quarter of the exhibits were Southeast Asian ceramics). Most of the ceramic exhibits were fragments. See Tokyo National Museum, 2000. ↩

-

See Hsieh, 2009, vol. I, pp. 122–123; vol. II, p. 70. ↩

-

Belcher, 1991, p. 66. ↩