Tiong Bahru: Exploring Singapore’s First Public Housing Estate

Tiong Bahru is a place of many faces. Originally known for its “aeroplane houses”, Singapore’s first public housing experiment once had a reputation as a haven for the mistresses of rich businessmen. These days, it is better known for its heritage housing, skyrocketing property prices and popular food establishments.

Origins of Tiong Bahru: Swamps and Cemeteries

The name Tiong Bahru is derived from the Hokkien word tiong (graveyard) and the Malay word bahru (new). The area originally contained a number of Chinese cemeteries, and its name is likely to have been coined to distinguish it from older cemeteries in the Chinatown area.1 A 1905 article in the Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society also notes that the Hokkien name for Tiong Bahru was O chai hng, which means “tapioca vegetable garden”. 2

Before 1926, Tiong Bahru consisted largely of mangrove swamps and several low hills, bordered by Sit Wah Road and Outram Road. The cemeteries included Si Jiao Ting, a public cemetery for the Hokkien community, and cemeteries for deceased with the surnames of Choa, Wee and Lim, as well as family-owned burial plots.3 One of the more famous burials in the area was that of philanthropist Tan Tock Seng. The cemeteries sat mostly on the hilly areas of Tiong Bahru, while squatters in attap and plank huts formed colonies in the foothills near the swamps. The squatters paid rent to the caretakers of the burial grounds, and those who lived over the swamps built their huts on stilts. The area also featured pig and duck farms, a sago factory, the Sungei Batu rubber factory and the Ghin Teck Tong temple.

The early 20th century saw the resident population of Tiong Bahru grow due to overcrowding in nearby Chinatown. However, the area’s infrastructure remained poorly developed and existing roads were not well maintained. This was evident when firemen were unable to reach the Sungei Batu rubber factory during fires in 1911 and 1914; in both cases, firemen could not drive their engines to the factory due to the condition of the roads, and had to haul their equipment via footpaths. In 1914, The Singapore Free Press described Morse Road as “dilapidated and dangerous” and Tiong Bahru Road as being “in a disgraceful state of neglect, being full of huge holes and ruts”.4 The presence of the swamps led to poor sanitary conditions and malaria, with Tiong Bahru noted as a mosquito-breeding area, although a 1918 report recorded that municipal work had greatly improved the drainage of the area.5

Development Begins: The Singapore Improvement Trust

In 1925, the Municipal Commission initiated a scheme to clear the land in Tiong Bahru, remove the squatters and their dwellings, and lay the infrastructure for a new town. Municipal health officer P.S. Hunter had earlier studied the sanitary and health problems of overcrowding in Chinatown, and recommended to create a well-planned suburb nearby to relieve the congestion. Tiong Bahru’s unsanitary conditions were also considered undesirable given its location near the General Hospital.6

In June 1926, a scheme to develop around 33 ha of land was approved. Under this joint Municipal-Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) scheme, the land was acquired for over $600,000.7 The goal was to provide plots of land that could be easily built up, and lay roads and pavements. The government would thus develop the land before selling it to prospective housing builders.

With the Singapore Improvement Trust Ordinance approved in 1927, work soon started on the slum clearance and land acquisition. However, the colonial government found it difficult to clear the squatter colonies, taking several years to evict over 2,000 squatters and demolish 280 huts.8 Several kampongs remained in Tiong Bahru and its surrounds, and new ones were to spring up in the future. Graves at the burial grounds were exhumed and moved to Bukit Brown Cemetery, while the hills were levelled and the soil used to fill up the swampy ground. Roads in the area were named after prominent businessmen and philanthropists of the period, including Khoo Tiong Poh, Koh Eng Hoon and Seah Eu Chin.9

By 1931, the land work, including the laying of roads, drains and culverts, had been completed at a cost of around $1.5 million. Over the next four years, the SIT sought to sell land sites to private developers for the development of residential property, but was unable to find buyers.10 In February 1935, the SIT decided to start housing development. SIT manager L. Langdon Williams, who was to direct the housing scheme, attended the International Town Planning Congress in London and visited British cities for ideas.11

Construction of the estate began in March 1936, and the first block of flats consisting of 28 units and four shops was completed in December that year. The first 11 families moved in on 1 December, paying monthly rents of $20 for a ground-floor unit and $22 for an upper-level unit. By 1941, some 784 flats in two- and three-storey blocks, 54 tenements and 33 shops had been built, accommodating over 6,000 people. The estate had a market, a restaurant, coffee shops, a shoe shop, a dressmaker’s shop and sundry shops. Residents comprised a diverse population of Chinese, Indians, Eurasians and Europeans.

[F]iremen were unable to reach the Sungei Batu rubber factory during fires in 1911 and 1914; in both cases, firemen could not drive their engines to the factory due to the condition of the roads, and had to haul their equipment via footpaths.

Advent of War: The Japanese Occupation

With Tiong Bahru’s development ongoing even as World War II approached, town planners built air raid shelters within the estate. The blast-proof shelters at Block 78 Guan Chuan Street remain intact as Singapore’s first air raid shelters located within a public housing estate, while another shelter at Eu Chin Street was later converted into a community centre.12 Children’s playgrounds were also turned into makeshift air raid shelters as the Japanese advanced towards Singapore.13

The Japanese invasion and occupation of Singapore interrupted the estate’s development, which had already cost a large proportion of the $10 million originally allocated to the SIT for slum clearance all over the island. The roofs of a number of Tiong Bahru flats were damaged by Japanese bombings, and during the Japanese Occupation, the flat roofs fell into further disrepair through vegetable cultivation and other unauthorised uses.14

The occupation saw a large number of new residents in Tiong Bahru, with an estimated 40 percent of the estate’s postwar population having moved in during this period. These new residents were recognised by the postwar British Military Administration, while tenants who had illegally sold their flats for thousands of dollars’ worth of occupation-era ”banana money” had their tenancies terminated after the war. Other tenants had sublet their flats, leading to the estate’s population nearly doubling to around 14,000.15

Postwar Growth and Renewal

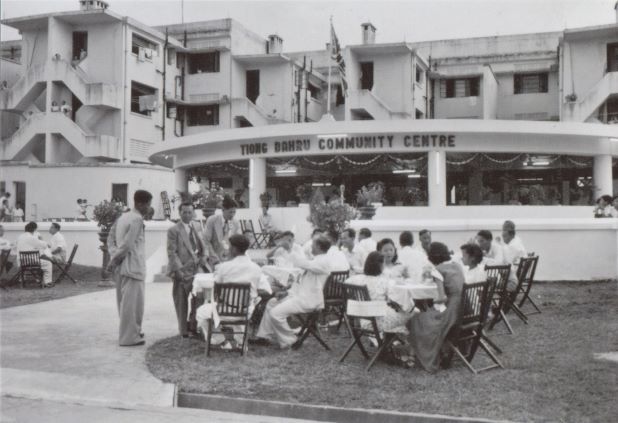

After the Occupation, construction continued on the housing estate. In 1948, a club was formed to manage the social, physical and cultural life and amenities of the community. By 1951, the estate had a physical centre, Singapore’s first community centre. The centre had its own civil defence group and auxiliary police force for the area.16 In 1961, the first polyclinic in Singapore opened in Tiong Bahru. Tiong Bahru flats continued to be in high demand, with thousands of applicants on the waiting list. By 1954, the SIT had added another 1,258 units to the estate.17

In the early 1950s, the population of Tiong Bahru stood at around 400,000. Besides those living in SIT housing, a number of attap hut villages sprang up on uncleared burial grounds. The Straits Times called the area “one of the worst attap slums in Singapore… haunted by a nest of gangsters and undesirable elements”.18 The remaining slums and grave sites on the fringes of Tiong Bahru were cleared by the mid-1970s.

In 1955, the SIT was dissolved and the People’s Action Party government that had come to power in 1959 instituted the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in its place. The HDB announced its first five-year building plan in December 1960, including the construction of some 900 flats at Tiong Bahru for lower-income groups. From March 1965, the HDB ended the rental policy of the prewar flats and sold a number of them to their occupants, and evicted the remaining tenants who did not take up the sale option. The postwar flats came under HDB management in 1973 and residents had their 99-year leases renewed.

In 1966, the HDB announced that as part of its second five-year plan, an $8.5 million housing scheme for 40,000 people would be developed at Kampong Tiong Bahru, which had been the site of several major fires.

Fires in Tiong Bahru

There were numerous fires in Tiong Bahru, both big and small, before the development of widespread modern housing in the area. In August 1934, more than 500 dwellings across the kampongs of Tiong Bahru, Bukit Ho Swee and Havelock Road were destroyed by what was then described as “one of the worst fires in years”. Up to 5,000 people were left homeless.

Fires in 1955 and 1958 left hundreds in Kampong Tiong Bahru homeless, leading to the formation of a volunteer fire-fighting force in 1958. The highly flammable materials used to construct attap huts in the kampongs and the densely packed nature of their layout meant that fires spread quickly and caused major damage. Another fire in February 1959 caused up to 12,000 to lose their homes and $2 million worth of damage.

On 25 May 1961, a fire that began near the site of the 1959 fire at Kampong Tiong Bahru spread across 100 acres, and the homes of nearly 16,000 people were destroyed. The Bukit Ho Swee fire, as it came to be known, is considered one of Singapore’s worst-ever fires and gave new impetus to the government’s policy of clearing attap hut settlements and shifting to flatted public housing.

Growth and Redevelopment

By the 1980s, Tiong Bahru was seen as an estate with a greying population and ageing facilities. The 1990 census showed that those aged above 60 made up the highest proportion of residents in the estate.19 However, a combination of redevelopment and an influx of new residents attracted to the architecture and culture of the area changed the demographics of Tiong Bahru in the early 1990s. A shopping mall, Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) station, new public housing and private condominiums sprang up around the area.

The iconic Tiong Bahru Market underwent a two-year, $16.8 million redevelopment, with the new building taking after the Art Deco architecture of the estate.

In 1995, a five-hectare site opposite Tiong Bahru Plaza, including 384 flats built in 1952, was chosen for the first Selective En-Bloc Redevelopment Scheme. The scheme was for older estates consider unsuitable for upgrading, and these 16 blocks of flats were acquired by the government and redeveloped into 1,402 new flats, more than three times the previous number.20

From the early 2000s, Tiong Bahru began to attract a new generation of residents. Drawn by the area’s unique architecture and heritage, the influx of young professionals helped rejuvenate Tiong Bahru’s community life and retail scene, with art galleries, bookstores, cafes, restaurants and specialist boutiques setting up shop.21

Conservation and Renewal

In late 2002, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) held a public consultation and exhibition of sites proposed for conservation. Tiong Bahru was not part of this exhibition, but was later included after a public show of support for the estate.22 In 2003, 20 blocks of prewar SIT flats were granted conservation status by the URA, which meant that changes to the building structures were restricted by URA guidelines. From the late 1990s and into the 2000s, both pre- and postwar SIT flats were highly sought after by home buyers, and property prices rose to some of the highest in Singapore.23

Two blocks of conservation flats were developed by Chinese firm Hang Huo Enterprise into the $45 million Link Hotel, a budget boutique hotel that was completed in 2007. The Link was joined by Hotel Nostalgia in 2009 and Wangz Hotel in 2010, giving Tiong Bahru the feel of a boutique hotel enclave.

Architecture and Culture

[Singapore Improvement Trust] architects and managers took inspiration from public housing in British new towns like Stevenage, Harlow and Crawley. These influences were applied to the estate’s flats and shophouses, creating a blend of imported and local styles.

SIT architects involved in the design of Tiong Bahru estate included Lincoln Page, Robert F.N. Kan and A.G. Church, who were influenced by the International Style popular in Europe during the period. The style spurned elaborate, decorative construction and focused on simple expressions of clear lines and planes.24 SIT architects and managers took inspiration from public housing in British new towns like Stevenage, Harlow and Crawley.25 These influences were applied to the estate’s flats and shophouses, creating a blend of imported and local styles.

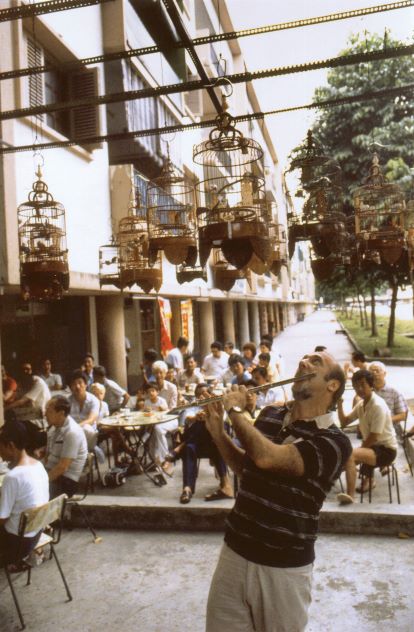

The layout of the estate incorporated plenty of open spaces, with an emphasis on small neighbourhoods. The prewar flats were neatly laid out and circled a central communal zone. This zone included a market and hawker centre, coffee shops, a pet shop and a Chinese temple. The hawker centre housed reputed chwee kuay (rice cakes), pig organ soup and bao (bun) stalls, and the pet shop and bird-singing corner attracted both local bird lovers and tourists. The bird corner at Block 53 along Tiong Bahru Road was started in 1957, and was flagged by international travel writers as a slice of heartland Singapore in the 1970s and 1980s.26 It closed for a period of redevelopment but has since reopened on the grounds of the Link Hotel.

The prewar flats showed the influence of the shophouse, the prevalent dwelling form among Singapore’s urban population at the time. The flats were based on a modified shophouse plan featuring courtyards, air-wells and back-lanes, but also combining the aspects of a modern apartment and designed in a way that provided a high level of privacy for individual homes.27 A new style took hold in the form postwar flats, which were slab blocks of long, narrow buildings bordered by greenery. These walk-up apartments had clean architectural facades with rounded balconies and exterior spiral staircases.28

In the first few decades following its prewar origins, Tiong Bahru estate gained the colloquial tag of mei ren wo (Mandarin for “den of beauties”). This nickname came about as the estate developed a reputation for housing the mistresses of many rich men, as well as nightclub singers and hostesses working in the nearby Keong Saik Road red-light district and Great World Cabaret.29 The prewar flats were also called puay kee chu (literally “aeroplane houses”) in Hokkien, as their design resembled that of the control tower at Kallang Airport, which was constructed around the same time. The estate was also dubbed “Hollywood of Singapore” by locals who had previously only seen flats in American movies.30

The regeneration of Tiong Bahru from the early 2000s has led to a sense of an incipient arts and culture scene taking root in the area, with new residents, art galleries and boutiques drawing inspiration from the heritage and culture of the estate while adding their own narratives to the Tiong Bahru story.31 The estate has also attracted artists and filmmakers: Tiong Bahru estate appears in scenes of Be With Me, a 2005 movie by local filmmaker Eric Khoo, while the 2010 short film Civic Life: Tiong Bahru features residents of the area and tells the stories of the relationships between the community and the environment.

REFERENCES

Ang, L. (1995, August 23). Tiong Bahru estate is maiden site for en-bloc redevelopment. The Business Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Bachtiar, I. (1993, July 29). Tiong Bahru: The next yuppie estate? The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Buy-it-or-quit tenants to protest against ‘high prices’. (1965, March 7). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chan, K.S. (2000, August 21). Aeroplane towers haven for good-time girls. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chin, K.K. (1991, January 2). Heart and soul. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

China’s Hang Huo Enterprise wins bid to convert Tiong Bahru flats to hotel. (2003, August 12). Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Chow, C. (2009, June 8). Niche accommodation in Tiong Bahru. The Edge Singapore.

Firmstone, H.W. (1905). Chinese names of streets and places in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula (53–208). Singapore: JMBRAS. (Call no.: RQUIK 959.5 JMBRAS)

Hari Raya inferno. (1961, May 26). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Improvement Trust flats occupied. (1936, December 2). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Jalleh, K. (1949, July 24). Tiong Bahru’s No. 3 wives. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Koh, T. et al (Eds.). (2006). Tiong Bahru. In Singapore: The encyclopedia. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 959.57003 SIN)

Kong, L. (2011). Conserving the past, creating the future: Urban heritage in Singapore. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 363.69095957 KON)

Lev, M. (1996, December 26). Songbirds still capture Singapore’s heart. The Orange County Register. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Loo, D. (2004, September 5). ‘50 flats in Tiong Bahru a big draw. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lou, K. (1990, December 5). Charms of Tiong Bahru. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Municipal Singapore. (1918, May 24). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

New block of flats. (1940, May 20). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ng, M. (2010, April 29). Tiong Bahru, the movie. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ng, T.Y. (2006, September 2). He wants to put Tiong Bahru on world map. The New Paper, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Overcrowding in Chinatown. (1930, June 26). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Perry, M., Kong, P., & Yeoh, B. (1997). Singapore: A developmental city state. New York: Wiley. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 PER)

Renovating Singapore. (1926, October 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Rubber factory fire. (1914, April 6). The Singapore Free Press, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B. (2003). Toponymics: A study of Singapore street names. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Tan, T.H. (2011, July 30). Tiong Bahru redux. The Business Times, pp. 2–3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Three Singapore kampongs in ruins. (1934, August 9). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tiong Bahru flats will house 1,000 by end of 1938. (1937, October 13). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tiong Bahru housing plan. (1935, April 20). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Town planning. (1926, June 15). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wan, M.H., & Lau, J. (2009). Heritage places of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.58 WAN)

Wong, T.-C., & Xavier, G. (2005). A roof over every head: Singapore’s housing policies in the 21st century: Between state monopoly and privatization. Calcutta: Sampark. (Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 WON)

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

Yeoh, B., & Kong, L. (1995). Place-making: Collective representations of social life and the built environment in Tiong Bahru. In B.S.A. Yeoh & L. Kong (eds.), Portraits of places: History, community and identity in Singapore. Singapore: Times Edition. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 POR)

NOTES

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

The Singapore Press, 6 Apr 1914, p. 12. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 May 1918, p. 10. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 1 Oct 1926, p. 11. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

Savage & Yeoh, 2003, p. 386. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 Apr 1935, p. 12. ↩

-

My Paper, 27 Jan 2012. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Jul 1949, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Nov 1951, p. 4. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Oct 1964, p. 8. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1995, pp. 89–115. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Aug 1995, p. 1. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Feb 2008, p. 86. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 5 Sep 2004, p. 25. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 5 Dec 1990, p. 4. ↩

-

Lev, 26 Dec 1996. ↩

-

Wong & Xavier, 2005, p. 46. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Jul 1949, p. 8. ↩

-

_The New Paper, 3 Sep 2006, p. 5. ↩

-

_The Business Times, 30 Jul 2011, pp. 2–3. ↩