Raffles and the Founding of Singapore: An Exhibition of Raffles’ Letters

Nearly 200 years after he set foot on Singapore to establish a trading post for the British East India Company, Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1781–1826) continues to fascinate and intrigue us. How else can you explain our penchant for naming all manner of things after him?

The world’s largest flower, the Rafflesia arnoldii, is named after him, as is the hotel that was once the world’s tallest, Swissotel The Stamford, and Raffles Hotel, Singapore’s oldest hotel. And then, there is Raffles Tailor, Raffles Photographer, Stamford Canal, Raffles Boulevard and the whole family of Raffles schools. What about the more than a dozen biographies of the man, not to mention a forthcoming version by noted British biographer Victoria Glendinning?

Even if the thousands of students force-fed a National Education diet of Raffles are probably quite jaded by the mention of his name, Raffles has worn well. He has not, like some of our more modern heroes, faded like the old history books that detail his story and deeds. The same students who have not heard of Toh Chin Chye still remember Raffles from their early history lessons. Come August this year, a new exhibition at the National Library will afford us another opportunity to revisit the life and exploits of this remarkable man.

Beyond the Visionary with Folded Arms

Powerful images have an uncanny hold on our memories and imaginations. Think of Raffles and there emerges the visage of a handsome visionary, looking purposefully in a distance, arms confidently folded, thanks to the iconic bronze statue of Raffles by English sculptor Thomas Woolner (1825–92), who never saw the man in the flesh.

Raffles was born on 6 July 1781 off the coast of Port Morant, Jamaica, on a ship captained by his father, Captain Benjamin Raffles. The Raffles family was not rich, but young Raffles went to school until his father could not longer afford to pay for his studies. In 1795, at the age of 14, he obtained a position as a clerk with the British East India Company, and two years later when his father died, he became the family’s sole breadwinner, providing for his mother and five sisters.

For a decade, Raffles enjoyed a career as a diligent, if unexceptional, cog in the gigantic organisation that was the East India Company. But things changed in 1805. That year, he married Olivia Marianne Fancourt, widow of Dr Jacob Fancourt (who had been assistant surgeon in Madras), and was sent to the Prince of Wales’ Island (Penang) to become assistant secretary to Philip Dundas, the newly appointed Governor of Penang. Out East, Raffles was to demonstrate his abilities and versatility; within two years, he was promoted to Chief Secretary to the Governor. With this appointment, Raffles’ salary was raised to £2,000 a year, a princely sum in those days.

Raffles and the Malay States

In 1807, Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 1st Earl of Minto and better known as Lord Minto, was appointed Governor-General of India. In Penang, Raffles and Olivia had befriended Dr John Leyden, the polyglot orientalist and naturalist whom Minto greatly admired; it was Leyden who drew Minto’s attention to Raffles. Between 1807 and 1810, Raffles had made two trips to Melaka which had been placed under British custody by the Dutch, who feared that the French might seize the colony. Based on the intelligence he gathered there, Raffles wrote a long memorandum on how to protect British interests in the region. He submitted this to his superior, the Governor, but the latter did nothing.

Minto was anxious that the French – who now occupied Java – might have further designs in the region which might thwart British interests. Leyden drew Minto’s attention to Raffles’ lengthy memorandum. Deeply impressed by Raffles’ memorandum, he told Leyden that he would be pleased to receive more information of this nature from Raffles. In June 1810, Raffles visited Minto in Calcutta and was appointed the Governor-General’s Agent in the Malay States. This meant that Raffles would report directly to Minto and bypass his superiors. Naturally, Raffles’ superiors grew suspicious and envious of him.

By January 1811, Minto decided that he would personally lead a British force to invade Java and get rid of the French. Sailing along with him in the June 1811 expedition were Raffles and Leyden. The conquest of Java was swift and Raffles was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Java, a post he held till 1816, when Java was returned to the Dutch at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars.

Setbacks and Triumphs

Raffles departed Batavia with a heavy heart. His wife Olivia had died at the end of 1814, and his former Commandant, Colonel Robert Rollo Gillespie, had levelled charges of maladministration against him in India. Raffles returned to London to answer these charges and to recuperate. There, he successfully defended his record in Java and was fully exonerated by the Court of Directors. The following year, he published his History of Java to wide acclaim and was knighted by the Prince Regent (later King George IV). He was feted in intellectual circles, making friends with many influential personalities, including Princess Charlotte, the Duke and Duchess of Somerset, William Marsden and Sir Joseph Banks. He was even elected Fellow of the Royal Society and was the toast of London high society.

Raffles sent Canning a memorandum entitled “Our Interests in the Eastern Archipelago”, which offered a blueprint on how Britain could secure its interests in the east, and proposed the establishment of a third British settlement.

Among those he met in London was George Canning, head of the Board of Control and later briefly Prime Minister of England. He sent Canning a memorandum entitled “Our Interests in the Eastern Archipelago”, which offered a blueprint on how Britain could secure its interests in the East, and proposed the establishment of a third British settlement (other than Penang and Bencoolen). It appears that it was about this time that Raffles began seriously looking at various options lying to the south of the Straits of Melaka to establish a new British settlement. With the French threat gone, the English now had to worry about the resurgence of Dutch power in the region.

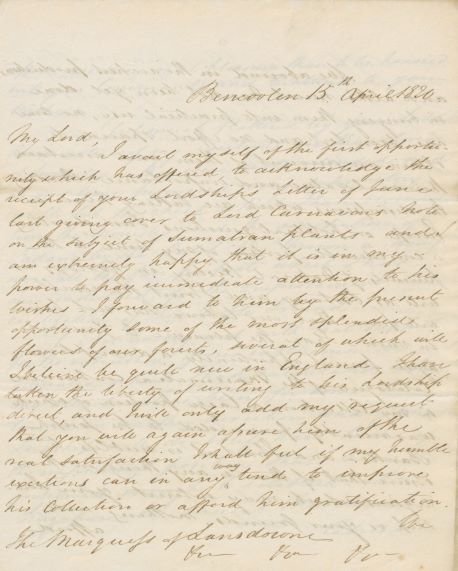

In 1818, as Raffles was due to return east to assume his post as Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (Bengkulu), the Court of Directors of the East India Company give him certain general advisory duties. He was tasked with reporting all happenings in the eastern archipelago and to “check Dutch influence extending beyond its true bounds”. It was in respect of these new duties that Raffles saw fit to write to Lord Moira, Marquess of Hastings, who was now Governor-General of India. The earliest letter from the Bute Archives stem from this period. Raffles urged Hastings to consider ways to stop the Dutch from reimposing their damaging trade restrictions, and once more pushed for the establishment of a new settlement in “the eastward”.

Anxious Days and the Founding of Singapore

Hastings, now impressed with Raffles, invited him to “a conference” in Calcutta. The two men met in September 1818 and Hastings signed a memorandum (most probably drafted by Raffles himself), giving Raffles leeway to act independently with respect to the establishment of a new settlement. However, he was not to tangle with the Dutch. Raffles then set sail for Penang, arriving on 29 December 1818 to meet with Governor John Alexander Bannerman, his immediate superior in the East. Though cordial, the meeting was tense. Bannerman was not keen on Raffles’ plans and was concerned that any new settlement would threaten the status of Penang.

Raffles had despatched Major William Farquhar, former Commandant and Resident of Melaka, to survey the islands at the tip of the Malay Peninsula and Johor Lama [including] the Carimon Islands (Karimun) and Singapore.

In the ensuing days, Bannerman tried to delay Raffles and prevent him from setting out on his mission to establish a new settlement. These were anxious days for Raffles for he knew that the Dutch were quickly taking steps to re-establish themselves in the region and to exercise suzerainty and control over the old Johor-Riau-Lingga empire, whose territory extended from Pahang to Bintan. To thwart Raffles, Bannerman appointed him as envoy to Aceh to settle a royal succession dispute and hold him in Penang. In the meantime, Raffles dispatched Major William Farquhar, former Commandant and Resident of Melaka, to survey the islands at the tip of the Malay Peninsula and Johor Lama. These included the Carimon Islands (Karimun) and Singapore.

On 18 January, Raffles managed to escape the clutches of Bannerman when the latter told him that his mission to Aceh had been delayed. Ever the opportunist, Raffles – who had his ships prepared for this purpose – departed Penang immediately in the dead of night. He informed Bannerman that since the mission to Aceh had been delayed, he would take the opportunity to catch up with Farquhar and his surveyors. Raffles, sailing on the Indiana, was not to catch up with Farquhar till 27 January 1819 at Carimon. That evening, agreeing to Captain Daniel Ross’ suggestion to next survey the island of Singapore, all seven ships in the flotilla sailed for Singapore.

The rest of the story is well known and does not bear repeating in great detail. Having ascertained from Temenggong Abdul Rahman that the Dutch had not yet established a settlement on the island, Raffles proceeded to sign a preliminary agreement with the Temenggong to allow the British to establish a trading “factory”. Capitalising on the succession dispute over the throne of the Johor Sultanate between Tunku Hussein (Tunku Long) and his younger brother Tunku Abdul Rahman, Raffles sought out Tunku Hussein, recognised him as sovereign and proceeded to sign the Agreement of Friendship and Cooperation that confirmed his earlier agreement with the Temenggong. After appointing Farquhar as Resident and Commandant of Singapore, Raffles left the island for Penang on 7 February.

Naturally, Raffles’ unilateral action infuriated Bannerman, who ordered him to get Farquhar and his troops off the island. The Dutch protested, arguing that they had a right to the island since it was part of the Johor-Riau-Lingga empire and they had an agreement with Sultan Abdul Rahman. The competing claims on the island were finally resolved with the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, under which the Dutch surrendered all claims to Singapore and handed the colony of Melaka to Britain in exchange for the ports of Batavia and Bencoolen.

The Letters on Show

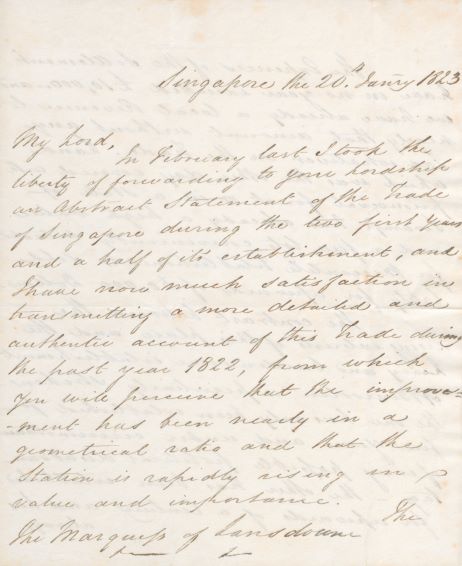

Exhibited at the National Library Singapore for the first time are 13 of 26 letters from the papers of Francis Edward Rawdon Hastings, First Marquess of Hastings, who served as Governor-General of India from 1813 to 1823. These letters were written to Hastings (known at the time as Lord Moira) between April 1818 and October 1824. Of these, the most important ones were those written almost contemporaneously with Raffles’ efforts to establish a new settlement in the “eastward”.

These letters are being exhibited through the generosity of John Colum Crichton-Stuart, Seventh Marquess of Bute. These letters were first brought to our attention by Dr John Bastin, the world’s leading scholar on Raffles. The Hastings Papers were acquired by John Crichton-Stuart (1847–1900), Third Marquess of Bute, sometime in the late 19th century. The Third Marquess was an industrial magnate, antiquarian, scholar and architectural patron and grandson of the papers’ owner. His mother, Sophia Frederica Christina Rawdon-Hastings (1809–59) was the second daughter of Lord Moira, First Marquess of Hastings.

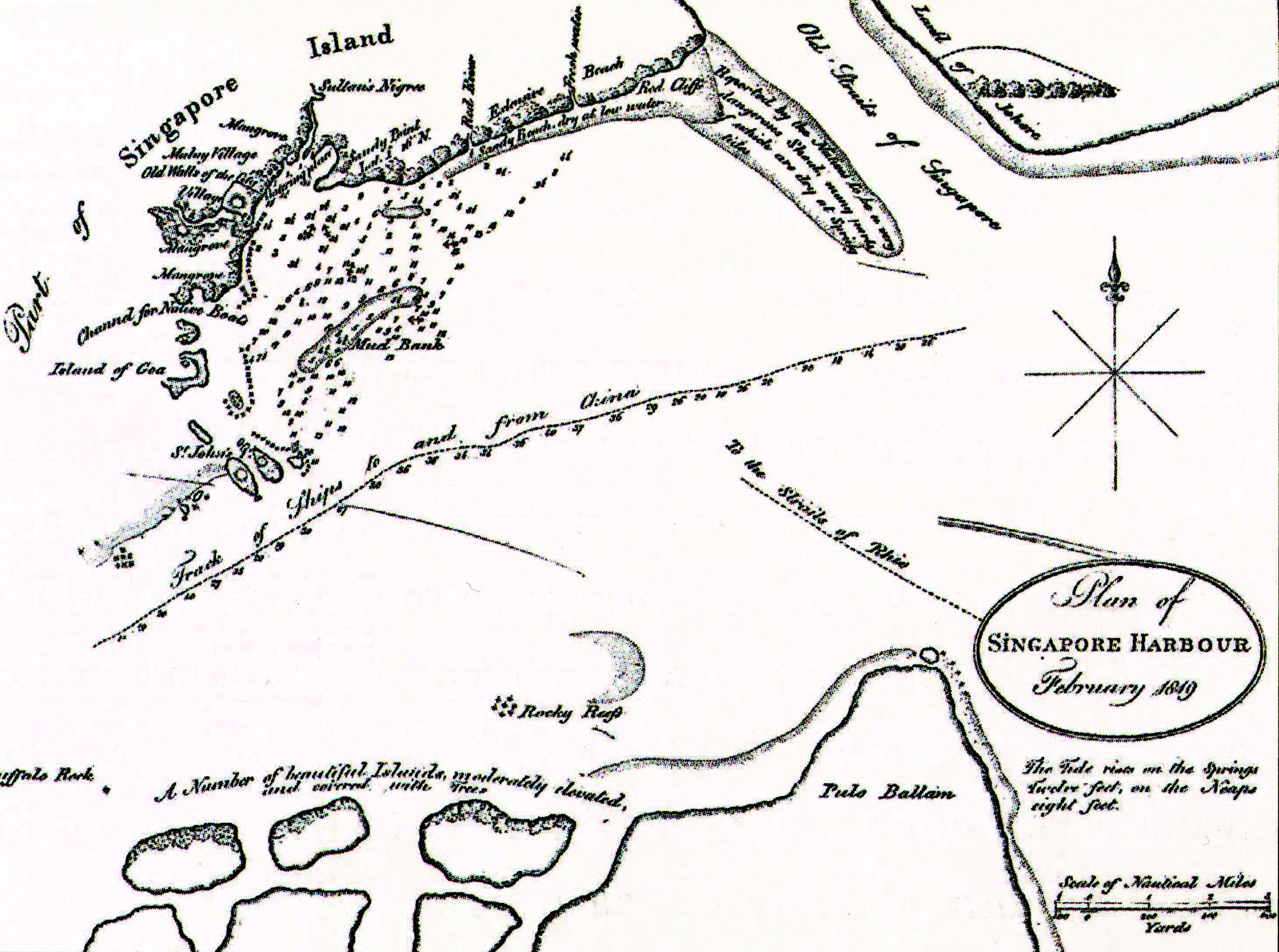

Also on display is a copy of what is believed to be the earliest map of Singapore drawn after Raffles’ landing. Dated 1820, it is the result of the first survey of the island and contains details not seen in subsequent maps. This map has never been seen outside of the Bute Archives.

The End

Raffles visited Singapore only twice more before he returned to London in August 1824. By then, he was in poor health but continued to be active in his intellectual pursuits, founding the Zoological Society of London in 1825 and the London Zoo. He died at Highwood House in Mill Hill, North London, a day before his 45th birthday, on 5 July 1826.