On the Waterfront: The Making of Singapore’s First High rise Skyline, 1918–1928

The town of Singapore and its architecture had always attracted attention. Even in the earliest days of the Settlement, visitors regularly commented on the fine buildings along the Esplanade, the neat and orderly streets and tree-lined thoroughfares, and the grand colonial-style residences of the European and Asian elites. From the outset, the progress of the town and its architectural landmarks were seen, quite rightly, as a reflection of the colony’s prosperity.

This is just as true for today’s Singapore, where the modern city-state is metonymically encapsulated by its cutting-edge architecture, designed by some of the world’s leading architects – I. M. Pei, Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa, Kevin Roche, Peter Pran and Zaha Hadid, to name just a few. Inevitably, it is the cluster of tall buildings that constitute the Central Business District – Singapore’s mini-Manhattan – that garners the most attention. There are three favoured viewpoints for photographing this scene. The first looks across the river from the north bank – either from somewhere between the two Parliament Houses, old and new, or else from the top of Swissotel The Stamford, which offers a splendid bird’s-eye view of the metropolis. The second perspective is from a vantage point situated somewhere between the Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and the ECP Bridge, while the third is from the front of the Marina Bay Sands complex, looking across the waters of Marina Bay towards Collyer Quay. A recent addition to the latter is a view of the city from the skyline swimming pool on top of the casino – an image featuring a botak (bald) swimmer in goggles making waves in the foreground became an instant icon for modern Singapore when it appeared in the press in 2010.

It is this vision of the city as a modern metropolis rising from the waves – or at least over the rim of an infinity pool – that I wish to consider in this essay. Not today’s image, but an earlier version from a period when Singapore first began to flex its financial muscles and emerge as a major player in the global marketplace shortly after the end of World War I.

In the 19th century, it was the view as one approached the town of Singapore from the sea that was especially admired. Frank Marryat, for example, who visited Singapore as a Midshipman in the Royal Navy in the 1840s, writes: “From the anchorage the town of Sincapore [sic] has a very pleasing appearance”, adding that “most of the public buildings as well as some of the principal merchants’ houses, face the sea”.1 This much-painted vista of Singapore from the roads was the “face” of Singapore throughout the 19th century and continued to be a defining view of the city right up to the late 1970s when the Marina reclamation scheme filled in the Inner Harbour and put the sea at one remove from the old waterfront.

Around the time that Marryat was writing, the principal focus of attention lay to the north of the Singapore River’s mouth, the locus of Raffles’ original “European Town”, with its elegant tropical Palladian architecture by George Coleman, juxtaposed with the soaring spires of the Christian places of worship – St Gregory’s, St Andrew’s and the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd – which were in effect Singapore’s first “skyscrapers”.

Gradually, however, the gaze of the onlooker began to shift south of the Singapore River after work began in 1858 on a land reclamation scheme on the seaward side of Raffles Place. The principal undertaking here was the construction of a robust seawall to a design by the eponymous Captain George Chancellor Collyer, Chief Engineer of the Straits Settlements. When this was completed in 1864, it made possible the development of a new commercial waterfront to the south of the Singapore River.

The earliest buildings on Collyer Quay were fairly modest, two-storey affairs: the ground floor comprising an arcaded verandah, or five-footway, with a cantilevered wooden balcony above. In one or two instances, a third storey was added in the form of a tower, or observatory, from the top of which a peon with an eye-glass could scan the horizon for incoming ships. In those days, if a cargo was unassigned, then whoever managed to meet the vessel first as she came into port, and befriended the captain before he dropped anchor, generally got the business.

Two early buildings of note along this new stretch of harbour front were the General Post Office and Exchange Building, completed in 1878 and 1879 respectively. Although they fronted onto Cavenagh Bridge Road, they were designed to be seen as much from the seaward side as from the land. In 1892, they were joined by a huge Victorian blockbuster, the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Building, standing at the corner of Battery Road and Collyer Quay – the same site that HSBC occupies to this day. The bank’s 1892 premises was an architectural tour de force in terms of its polygamous marriage of disparate architectural styles – Renaissance, Baroque, Queen Anne and Gothic, with a Roman portico tacked onto the front by way of an entrance. An early work by engineer architects Messrs Archibald Swan and James Waddell Boyd Maclaren, it was, in the view of The Straits Times, “the most commanding building… yet erected in Singapore”, and it completed the lineup of waterfront buildings for the 19th century.2

There were further additions to the waterfront in the early 20th century, the three most notable edifices being Winchester House (1904), The Arcade (1909) and St Helen’s Court (1916).3 Winchester House, at four storeys, was arguably Singapore’s first bona fide high-rise building, and it was also the first to have an electric lift installed, though not until 1906. With a colonnade of Roman Doric columns in the round at street level, and lots of rustication, quoins and other Classical detailing above, it certainly stood out from its rather more perfunctory 19th-century neighbours, which is no doubt what the owner, Towkay (loosely translated as “boss” in Hokkien) Loke Yew, intended. But It was somewhat eclipsed five years later by what was probably the most remarkable building to have graced Singapore’s waterfront: The Arcade, an extraordinary Orientalist confection “built according to Arabian and Moorish designs”, with a couple of copper onion domes on top.4 Designed by Scottish architect David McLeod Craik for the Alkaff family, The Arcade comprised a glass-covered walkway, or atrium, which extended from Collyer Quay all the way through to Raffles Place. With rows of shops on each side and a restaurant in the middle, plus two floors of offices above, The Arcade prefigured, on a modest scale, many of today’s shopping complexes. Lastly, there was St Helen’s Court, headquarters of the Asiatic Petroleum Company and the Straits Steamship Company. At five storeys, St Helen’s definitely put both Winchester House and The Arcade in the shade.

These noble edifices aside, the majority of buildings on Collyer Quay up until the end of World War I were two-storey affairs (with the exception of the odd lookout tower), dating back some 50 years to the completion of Collyer Quay in the late 1860s. As for the new additions, imposing though they were in their way, they were still firmly situated in the 19th century; the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building, just 20 years on from its grand opening, already seemed like an architectural dinosaur from another era.

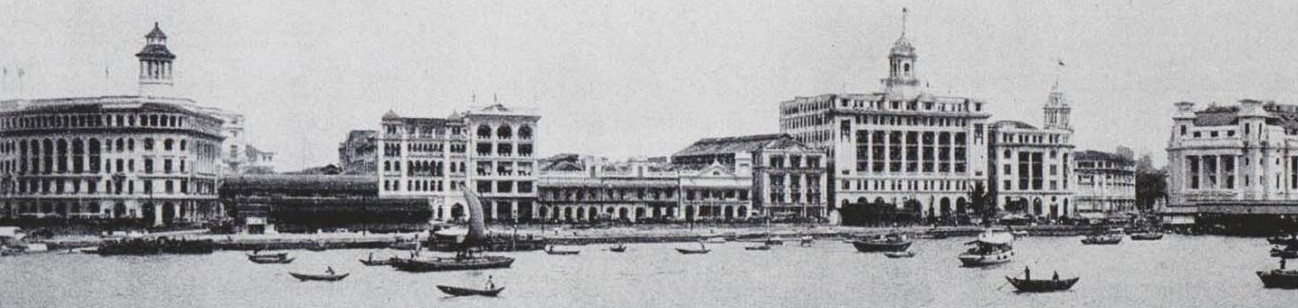

Then, suddenly, in the space of the 10 years that followed the end of the war in Europe in November 1918, we see a complete transformation of the waterfront from a relatively homogeneous parade of low-rise 19th-century godowns (with one or two exceptions) into a glamorous, modern skyline that, architecturally speaking, was situated somewhere between the London Embankment and the Shanghai Bund.

In order to fully appreciate how this came about, we need to understand that Singapore emerged from World War I in a very strong position on several fronts. The price of Malayan rubber was high, while the tin market, though it had been in recession during the war years, was about to make a brilliant recovery. At the same time, property prices and the construction industry were booming, and shipping was rapidly returning to normal.

Meanwhile, during the war there had been a complete makeover of the dockyards at Keppel Harbour, which now boasted the second-largest graving dock in the world, as well as a greatly extended wharf at the huge new Empire Dock, which had only been completed 1917. Work was also just about to begin on a causeway linking Singapore with the Malay Peninsula. Completed in 1923, the Causeway enabled goods and passengers to travel by train all the way from the terminus at Tanjong Pagar to the town of Prai in Province Wellesley, which was the mainland train station for the island of Penang. The ultimate aim, however, was a continuous rail link that would connect the Malay Peninsula, via Burma, with British India.

Strategically, the conflict in Europe had underlined Singapore’s importance in times of war as a regional communications hub for cable and wireless telegraphy, while Singapore’s military significance similarly increased, with Viscount Jellicoe, former First Lord of the Admiralty, describing Singapore as “undoubtedly the key to the Far East”. As well as plans for a massive new naval base, his fact-finding mission to East Asia in 1919 also led to the construction of a Royal Air Force station in Seletar (1927–28). The latter, though primarily intended to serve a military purpose, also gave Singapore its first proper aerodrome for civil aviation. Regular passenger and postal air services were, admittedly, still some way off, but the potential of civil aviation was already recognised in 1919, and it was simply just a matter of time before it became a reality.

In short, as the war in Europe finally drew to a close in 1918, Singapore was extremely well positioned both economically and in terms of its infrastructure to make the most of the resumption of normal trading along with the economic upturn that accompanied it. Although there was a recession looming, no one knew about it then.5 Rather, this was a period of optimism and celebration, with the upcoming centenary of the founding of Singapore by Stamford Raffles to look forward to. Raffles’ cherished dream of establishing a “great commercial emporium” in the East was, by then, very much a reality.

It is no coincidence, then, that it is precisely at this point that we see a sudden burst of building activity taking place at Collyer Quay which, in the space of just 10 years, would be completely transformed by the addition of four major new buildings. They were, in order of appearance, the Ocean Building (1922), the Union Building (1924), a new Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Building (1924) and the General Post Office or Fullerton Building (1928).6 These were not just new buildings, but buildings of a kind never seen in Singapore before – huge, corporate blockbusters, built to the latest designs, that gave Singapore its first high-rise skyline, a skyline that before the decade was out would be drawing comparisons with London, Liverpool and Shanghai.

The first of the postwar behemoths to go up at Collyer Quay was the Ocean Building, the new headquarters of the Ocean Steamship Company, more popularly known as the Blue Funnel Line, which had one of the largest fleets operating in the Far East. The design of the Ocean Building is credited to British engineer Somers Howe Ellis (1871–1954), who was Chief Civil Engineer of the Ocean Steamship Company from 1919 until his retirement in 1939. It was situated at the corner of Collyer Quay and Prince Street – the site occupied by today’s Ocean Building – and replaced an earlier two-storey structure that had been the premises of Blue Funnel’s Singapore agents, Mansfield & Co. The contrast between the new and the old could not have been greater. Five storeys in elevation, the main part of the building was a few feet higher than St Helen’s Court, which until then had been the tallest building by the waterfront, but then there was a 50-foot tower on top that turned the Ocean Building into a veritable “skyscraper” by the standards of the day.

To think that a building of such size and mass could be erected on ground that was far from firm was entirely due to the employment of the latest construction techniques: a concrete frame with masonry infill that was then covered over with a layer of artificial stone or “cladding”. This method is, of course, standard procedure in today’s architecture, but at the time the Ocean Building was going up, it was still considered innovative and certainly had not been used on this scale in Singapore before. And it was not just the size of the building that astonished people: it was also massive in terms of its composition – that is to say, the size and proportions of the Classical elements and ornamental features that made up its facade were equally monumental in scale.

Municipal Architect Alexander Gordon explained this new aesthetic in an address that he gave to a lunchtime gathering of the Singapore Rotary Society at the Raffles Hotel in October 1930. He began by noting that since there was no tradition of permanent architecture indigenous to the region, as there was, say, in India, “the more important buildings are now being erected in the modern classic style [which] has evolved from a study of the old Greek and Roman buildings adapted to modern construction and requirements”.7 “These new buildings,” Gordon continued, “are designed on a much bigger scale than the old Renaissance or classic buildings seen here. You now design on a larger unit.” By way of example, Gordon compared the Hotel de l’Europe on St Andrew’s Road, erected 1904–07, with its next-door neighbour, the recently completed Municipal Offices (later known as City Hall, now occupied by the National Art Gallery, Singapore). “There is very little difference in height or frontage,” Gordon observed, “yet the scale seems so much bigger. Whereas in the old type, an elevation would have a base with two three colonnades one above the other, the front being divided into approximately equal divisions vertically, the new type has a massive base, one tall dignified colonnade with cornice and parapet in proportion.”8 According to Gordon, “the modern classic, aims at bigness, simple dignity and the cutting out of superfluous features and decorations”,9 and these qualities were characteristic features of all the new buildings erected on Singapore’s waterfront between 1918 and 1928.

This raises an interesting point, however, regarding the perceived modernity of Gordon’s “modern classic” style. From today’s perspective, the Ocean Building, with its arcaded elevations, rusticated facade and rotunda-like tower, seems anything but modern. At the time, though, none of this was felt to be in anyway anachronistic; contrary to being an oxymoron, “modern classic” was very much the architecture of choice for large civic or commercial buildings in the decade following the end of World War I. Nowadays, there is an almost intuitive tendency to think of modern architecture between the two world wars in terms of the glass-and-steel erections of the German Bauhaus school, or Le Corbusier’s “purist” white cubes, or Mies van der Rohe’s minimalist Barcelona Pavilion. In actual fact, the vast majority of new buildings erected during this period –certainly in the 1920s, but also the 1930s – were conceived in the Classical manner. Indeed, as architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock points out, “Through at least the first three decades of the twentieth century most architects of the western world would have scorned the appellation ‘modern’, or, if they accepted it, would have defined the term very differently from the way it [is] understood [today].”10 Still deeply steeped in the historicism of the 19th century, the term “modern”, to them, generally meant designing buildings in the grand Classical tradition, while making the most of recent advances in construction techniques – steel and reinforced concrete, artificial stone, plate glass, electric lifts and services, and so on.

The continued preference for Classically-informed buildings was not because the general public was unaware of the “new architecture” of the early Modernists; it was simply not well received, whether in Europe or here in Singapore. “Modern German dwelling houses look like the products of a cubist or futurist nightmare,” declared the editor of The Straits Times in June 1929.11 “Although they are obviously designed to act as sun-straps, there is no architectural merit in the utilitarian purpose. They are odd, uncouth, apparently unfinished. The average child can construct something aesthetically more pleasing with a Meccano set.”12

It took close to three years for the Ocean Building to be completed, but the wait, it seems, was worth it. “An imposing pile,” proclaimed The Straits Times at the official opening on 24 March 1923, “that it is the handsomest building in town admits of no doubt.” It soon had its rivals: followed, a year later, by the Union Building and a new Hongkong & Shanghai Bank, which replaced the old Gothic pile on the corner of Collyer Quay and Battery Road. Both these buildings were designed by Denis Santry of Messrs Swan & Maclaren, who had joined this most prestigious of architectural practices just after the end of the war. Santry had previously worked in South Africa, where he is recognised as the father of the South African Arts and Crafts Movement, but his Hongkong & Shanghai Bank was anything but Arts and Crafts in style. It was described at the time as being in the “English Renaissance” style – that is to say, Gordon’s “modern classic” style – and it was another corporate blockbuster.

The new bank building comprised a rusticated arcade at street level, surmounted by a grand colonnade of Ionic columns rising through three storeys to support an attic floor, the whole being surmounted by a rotunda and dome.13 In terms of the materials, too, this was a very lavish affair. For starters, there were four pairs of bronze entrance doors, each pair measuring 8 feet wide by 14 feet high, and weighing 3 tons, while the main banking hall had marble columns topped by brass capitals, as well as marble floors throughout – even the cashiers’ counters were marble. To add further to this magnificence, the space was lit from above by two domed lights, or lanterns, executed in stained glass, which, according to The Straits Times, created “a cathedral like effect”.14

This was corporate power dressing taken to the extreme, the mercantile equivalent of “shock and awe” tactics, intended to impress upon the Singapore public the Olympian stature of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in the world of Eastern finance. But it was not the last word in ostentation on Singapore’s waterfront in the mid-1920s: that honour was reserved for the bank’s next-door neighbour, the Union Insurance Society of Canton.

The Union Building was a one-and-a-quarter-million-dollar, seven-storey extravaganza, surmounted by a 60-foot tower, the top of which stood 173 feet above street level. Although two storeys taller than its neighbour, the rusticated arcade on Collyer Quay matched that of the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank in scale and proportion, creating a sense of harmony at street level. The façade above was dominated by a majestic colonnade of Ionic columns, bookended by tall panels rising through four storeys, with huge bronze medallions at the top, some 8 feet in diameter, bearing the coat of arms of the Society. A bold, dentilated cornice with a 7-foot projection – “a particularly ticklish piece of engineering work”, according to The Straits Times15 – completed the main facade, with a stepped-back attic storey above. The crowning glory, though, was undoubtedly the central, rotunda-like tower, surmounted by a stepped dome.

Like its neighbour, it also had a pair of monumental bronze doors, measuring 15½ feet high and 8 feet wide, which opened onto a broad flight of stairs leading up to a 50-foot hall, lit from above by a glazed skylight. Huge doors – again cast in bronze – led to magnificent suites of offices on either side, with coffered ceilings 20 feet high.16

No expense was spared on the materials either. A feature in The Singapore Free Press, written in January 1924 as the building was nearing completion, tells us:

The final building to complete Singapore’s new-look waterfront in the 1920s was the new General Post Office, otherwise known as the Fullerton Building,17 erected on the site previously occupied by the old Post Office and the Exchange Building. The site was of course superb – “probably no structure in the East could have a more commanding site”18 – and mindful of this, the government decided to host an open competition to ensure that the location got the building it deserved.

The competition was won by the Shanghai practice of Keys & Dowdeswell, with the eponymous partners, Major P. H. Keys, FRIBA, and Frederick Dowdeswell, ARIBA, moving to Singapore to start work on their commission in May 1920. Sketch plans and the principal elevations were displayed in the Legislative Council Chamber for a month. Approval had been given to go ahead with the working drawings when it was suddenly decided that owing to the uncertain financial climate – this was the time of the 1920 US recession, which was accompanied by a corresponding crash in tin and rubber prices – the building should be postponed until the economy brightened.19

In the event, work did not begin on site until 1924, by which time Keys and Dowdeswell had been inducted into the colonial civil service as government architects. The Post Office was their biggest project to date. Indeed, it would be the biggest of their career: a massive seven-storey structure, plus basement, “the largest building of the kind ever built in Singapore” – The Straits Times of 9 January 1924 reported. It also had a budget to match: a colossal $4,098,808, which at the time was by far the largest figure ever spent on a building project in the Straits Settlements.20

The biggest problem faced by the contractors was providing adequate foundations for such a massive building on a site that was so close to the sea and on ground that was not very firm to begin with. The best solution, it was decided, was to employ the so-called “raft” method of foundations – basically a huge platform of cement which “floated” on the soil beneath – rather than resort to piles. This involved digging down through a strata of boulders and clay to a point 16 feet below ground level. Some 40,000 cubic yards of soil were removed from the site, while pumps worked day and night to prevent the hole from filling up with water, since it was well below the tidal level on the other side of Captain Collyer’s seawall.21

The Fullerton Building was finally completed in June 1928 to much acclaim. It was the view of The Straits Times that “the Post Office building, with its walls towering 120 feet from the ground, its fluted Doric colonnades on their heavy base, its lofty portico over the main entrance, and the 400-foot frontage along the waterfront, adds immeasurably to the dignity and solidity of central Singapore”.22 The Singapore Free Press similarly thought the Fullerton “a public building worthy of the city and port of Singapore”, and reckoned that “for a time a visit to the new Post Office will be almost an awesome experience”.23 Governor Sir Hugh Clifford, who officiated the opening ceremony, was in no doubt that the new Post Office was “the most imposing [building] at present existing in the Colony of the Straits Settlements”, adding that it “will be for many years, one of the principal landmarks in Singapore”. And he was right: even today, despite the dramatic backdrop of glass and steel that towers behind it, the Fullerton Building still retains a kind of monumental grandeur that easily competes with its lofty but less substantive neighbours.

The Fullerton Building was the last of the four major building works undertaken on Singapore’s waterfront in the 1920s. Clifford Pier would subsequently be added to the ensemble, but work on that did not begin until 1930 and the pier obviously did not contribute to Singapore’s changing waterfront skyline. Indeed, there were no significant additions to the waterfront until after World War II, when the Bank of China and the Asia Insurance buildings were erected in the mid-1950s. In the meantime, it was the four Baroque blockbusters from the 1920s that held pride of place: they were Singapore’s first skyscrapers,24 impossibly tall, or so it seemed back then, with their soaring towers and rotundas boldly silhouetted against the sky like a display of gigantic wedding cakes.

“There are few Oriental cities which can boast of a nobler and more inspiring group of buildings than that which is now seen by the citizen of Singapore as he passes over Cavenagh or Anderson Bridge,” observed The Straits Times in an article published on the eve of the official opening of the Fullerton in June 1928.25 “On a bright tropical morning, with flags lending bright touches of colour to their pillared, galleried masses, these new buildings on Fullerton Road and Collyer Quay give [even] the most unimaginative a glimpse of the power and romance of Eastern commerce.” Local author Roland Braddell felt that Singapore in the early 1930s was “so very George the Fifth… most of the big buildings are quite new and if you are English, you get an impression of a kind of tropical cross between Manchester and Liverpool”.26 Similarly, Robert Bruce Lockhart, returning to Singapore in 1935 after a quarter of a century’s absence, thought that contemporary Singapore resembled an “international Liverpool with a Chinese Manchester and Birmingham tacked on to it. Its finest buildings are modern”.27

The comparisons with Liverpool are especially revealing because this was a time when Liverpool proclaimed itself to be the “Second City of Empire”, with a port that was second only to London in size and importance. And it was not just Liverpool that Singapore resembled, but also Shanghai. A photograph of the Singapore waterfront, which appeared in The Straits Times of 2 March 1935, was accompanied by the caption, “What China Coast people call the ‘Bund’”. This was precisely the kind of impression that was intended for Singapore in the 1920s – that of a city on the move. It was an era of optimism, energetic growth and expanding horizons, the economic recessions of the early 1920s notwithstanding. This is when we see Singapore transcend its traditional role of regional entrepot and interlocutor between Asia and Europe, to take up a position on the international stage as a global port-city with connections reaching around the world – to Japan, Russia, the Americas, Australia and South Africa, as well as Britain, India and Europe. It was also a time of rapid social change and political development – not something I have been able to consider here – reflected in the lifestyles and aspirations of the people. By the end of the decade, Singapore could properly be considered a modern city in every sense of the word and it was precisely this message that the buildings down on the waterfront set out to capture and convey, for then, as now, it was Singapore’s corporate “skyscraper” architecture which, more than any thing else, proclaimed Singapore’s status as a thoroughly modern 20th- or 21st-century metropolis.

Dr Julian Davison was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow from 2009 to 2010. He obtained his PhD in Anthropology from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He is the author of Black and White: The Singapore House, 1898–1941 (2006) and Singapore Shophouse (2010).

Dr Julian Davison was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow from 2009 to 2010. He obtained his PhD in Anthropology from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He is the author of Black and White: The Singapore House, 1898–1941 (2006) and Singapore Shophouse (2010).REFERENCES

Arcade for Singapore. (1907, October 30). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Arrangements. (1894, November 1). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Bastin, J. (Ed.). (1994). Traveller’s Singapore: An anthology. Kuala Lumpur: New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 TRA)

Beautifying Singapore. (1924, January 17). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Braddell, R. (1934). The lights of Singapore. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BRA; Microfilm no.: NL25437)

Building on city swamps. (1930, October 25). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Government buildings. (1920, September 30). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Hitchcock, H.R. (1958). Architecture: Nineteenth and twentieth centuries. London: Penguin Books.

Lockhart, R.H.B. (1936). Return to Malaya. London: Putnam. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 LOC)

New Post Office. (1924, January 9). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Past and present. (1928, June 27). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore development. (1924, January 23). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The Hongkong Bank. (1921, November 16). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The new architecture. (1929, June 10). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The new Post Office. (1928, June 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The Post Office. (1928, June 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

The Straits Times, 1 Nov 1984, p. 2. ↩

-

These are the years the buildings were completed. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Oct 1907, p. 7. ↩

-

This was the 1920–21 US recession that caused the prices of rubber and tin to crash. ↩

-

These are the years in which the buildings were completed. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 25 Oct 1930, p. 12. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 25 Oct 1930, p. 12. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 25 Oct 1930, p. 12. ↩

-

Hitchcock, 1958, p. 531. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 10 Jun 1929, p. 10. ↩

-

Meccano is the brand name of a model construction kit comprising reusable metal strips, plates, angle-girders, axels, wheels, gears and so forth, which can be connected together using washers, nuts and bolts. Invented in 1901, Meccano is still manufactured today in France and China, but probably reached the height of its popularity between the two world wars, when it provided an invaluable introduction to the principles of mechanics and engineering for boys who were so inclined. ↩

-

The rotunda was removed sometime in the mid-1950s. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Nov 1921, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Jan 1924, p. 12. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), 17 Jan 1924, p. 12. ↩

-

The Fullerton Building was named after Sir Robert Fullerton (1773–1831), first Governor of the Straits Settlements, during the time of the East India Company (1826–30). ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Sep 1920, p. 7. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), 23 Jun 1928, p. 11. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), 23 Jun 1928, p. 11. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 9 Jan 1924, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 Jun 1928, p. 9. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), 27 Jun 1928, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 4 Feb 1922, p. 10. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 Jun 1928, p. 9. ↩