Books that Shaped the World

The importance of books lies in its substance and not its form. Whether on page or in pixel, the ideas perpetuated by books will continue to influence people and communities.

Over a year ago, as part of the lead-up to the first International Summit of the Book in 2012, the Library of Congress embarked on a project to create a list of books, mainly titles by Americans that have shaped the United States in crucial ways. The list was intended to spark a national conversation on books that have influenced American lives and society, whether they appeared on this initial list or not. This was inspired by a project by the British Museum a few years ago which sought to identify 100 objects that shaped the world.

For our project, Library of Congress curators identified the books and displayed copies of them in an exhibition. Our list of “Books that Shaped America” generated tremendous reactions from all around the country. People weighed in, as we had hoped, and took part in a discussion of the works that were on the list as well as books that were not on it but they felt ought to be. Through our website, we invited people to send us their comments, including nominations of books that they felt should be on the list. This generated thousands of responses, which persuaded us to make additions to the list, which now totals 100 books.

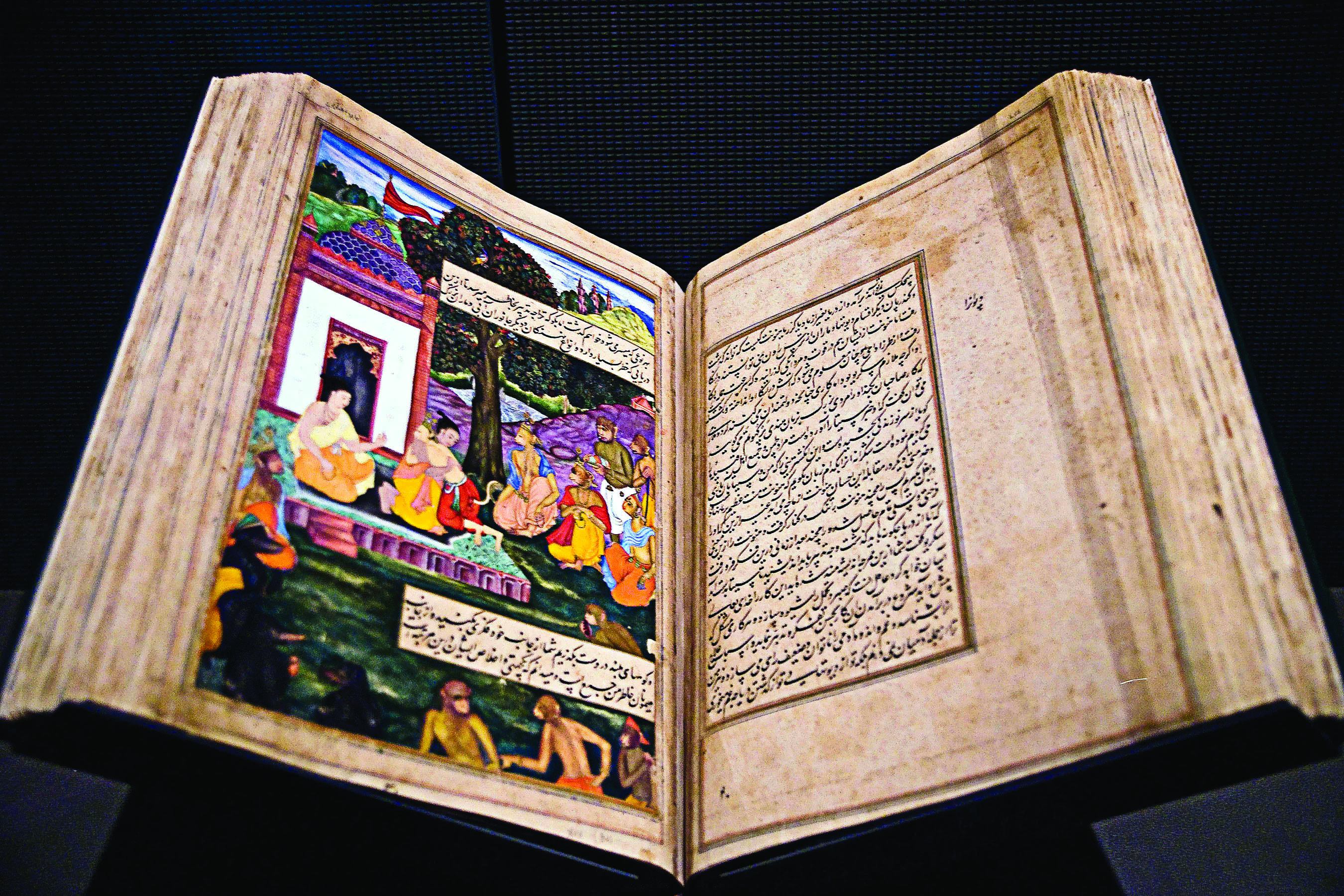

Beyond shaping America, books have created civilisation in a very real sense. Books have evolved from scrolls to codexes, to books with bound pages with a table of contents and an index, and it is possible to use the latter as an introduction to critical thought. It represents a whole new phase that first began with the manuscript way back in the fourth century.

Books that Have Shaped Us

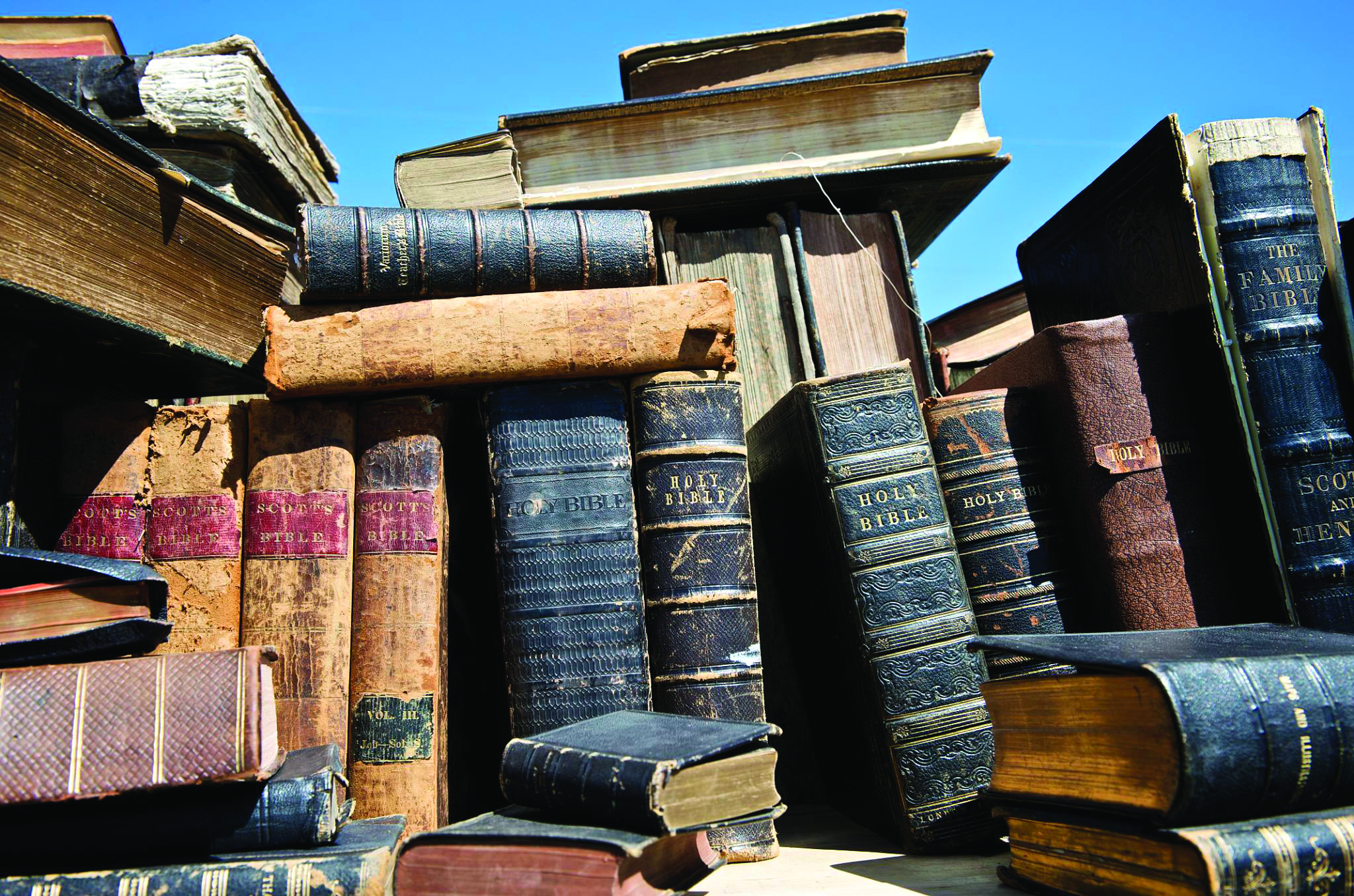

What we might call the founding books of civilisation are in many ways the books of the great religions. These include the Christian Bible, much of which is based on the Jewish Bible. Then there is the Koran, the last of the great prophetic, monotheistic books. The Chinese and the Indian traditions are also part of the basis of world civilisation. There is the Chinese Book of Lessons that contains Confucius’ Analects – the basis of education in China and for the civil service exams taken by Chinese officials for a thousand years. India produced the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, two great Hindu epics and fundamental doctrines originally published in Sanskrit and translated into many languages of the Indian subcontinent. These great epic poems, in a way, were the basis of much of Hinduism. Also noteworthy is Saint Augustine’s The Confessions of Saint Augustine and The City of God, which formed the basis of medieval thought and the concept of another spiritual world. These are all examples of great founding documents of civilisation.

The great founding epics of the Western tradition, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which are almost as old as the oldest Indian and Chinese works, are not to be forgotten. The first work on history is The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. I remember as an undergraduate in college hearing former Secretary of State General George C. Marshall give a speech, just before he announced the Marshall Plan (officially known as the European Recovery Programme, which lasted from 1948 to 1951). He said that he had been reading the aforementioned book and that it gave him guidance about the postwar world. Thus, that work of founding importance in Western history retains its importance even today.

In terms of philosophy, one must consider Aristotle’s work. It was the basis of the theology of the Latin Church, which penetrated from Greece into the Islamic world, then into the Christian world and Jewish thought. All kinds of secular thought, and even early governmental thinking in the West, had its roots in the philosophical works of Aristotle. If I had to choose a particular work of Aristotle as being especially influential, I would select the edition of his work that was published in Venice in the early modern period.

When considering the founding books of civilisation, the rise of science must be taken into account. For example, there are the fundamental works of Copernicus, but perhaps the most important of all in the history of science are the principles of natural philosophy by Isaac Newton, who gave us the law of gravity and so much else.

In terms of social science, one has to go to the Muslim world and Ibn Khaldun. Ibn Khaldun was born in what is now southern Spain and ended up being a founding figure in the northern African world. His Prolegomena and his longer seven volumes associated with it can be considered the first works on world history. He wrote a history that was also a treatise on sociology, geology and an analysis of the movement from rural to city. He was the first great world historian. Arnold Toynbee said Khaldun was the greatest world historian of all, but alas he is not very well known. When I was teaching world history, I always began with a reading of Prolegomena and students were astonished that anyone could write that way in the 14th century.

Some of the founding great novels have had a hand in influencing the modern world, particularly Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which was beloved not only in Spain but throughout the great Spanish empire. Another work that helped define and usher in the modern world was the Code Napoléon.

A great founding book that first explained Africa, particularly northern Africa, on a broad scale was Della Descrittione dell’Africa by Leo Africanus. Africanus, a convert to Christianity, spent a great deal of time in Timbuktu, a city known as a great repository of African, French and Muslim-Arabic cultures, as well as a great centre of learning. Africanus wrote about Timbuktu and other parts of Africa. Della Descrittione dell’Africa was called a cosmography and a geography. Its original version was published in both Italian and Arabic, pointing out the many links in the Mediterranean world among the three great monotheistic religions and also the different languages.

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations highlights the beginning of economics and the idea of a free, uncontrolled economy. And, of course, Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, which held a very different view, must be mentioned.

In the world of drama, one might pick something from Sophocles. One would also have to select something from Shakespeare. For example, Hamlet might be chosen because it created the most controversy and discussion, and contains the most psychoanalysis. Furthermore, it has some of the greatest soliloquies in English, or in any language. In terms of the great novels, I would pick Tolstoy’s War and Peace because it deals with the great problem of the modern state: war and peace. It also deals with family life and the mystery of history as distinguished from the analysis of history that was received from earlier historians, such as Thucydides or even Khaldun.

In addition to those mentioned so far, there is a whole range of works by other thinkers one would want to include such as Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. Indeed, Freudian concepts have become so familiar that we forget how widespread and how important they are.

These are some of the people whose books have shaped the world. It is important to remember that the defining thing about a book is its length, which produces a cumulative impact that is distinguished from a talking point, an argument, or any other use of language for some small, pointed purpose. The book’s length is the important thing, regardless whether it is read as a codex or on a Kindle.

Now we have the digital universe, but we also have the possibility and the importance of the book-length object. For us at the Library of Congress, the crucial challenge and opportunity is to integrate the old with the new, keeping them all together as different forms of knowledge, creativity and human expression, while retaining the values of book culture including that of dialogue and argument, and the idea of cumulative knowledge.

This is what you get at libraries, which are consolidations of the different forms of creativity and knowledge. And this is what we need in the future, wherever we go: new techniques for holding information to supplement but never supplant the wisdom and power contained in books and the imagination they can create and feed. Nobody can agree completely on the ten, or the hundred, or the thousand books that most defined and shaped our world, but we must always remember how important they are in our own lives, and how important they are in the broader life of humanity.

Dialogic Culture via the Book

As the 2013 International Summit of the Book looks to the future of the book culture and its values, it is helpful to examine the unique role of the book in dialogic culture. Simply put, books enable dialogues between readers and writers. They provide us with voices and experiences from other times and places, affect us with their marvellous stories, and make us more humane and civilised. All this is the beginning of the dialogic culture, which is essential for a democracy and helpful for a dynamic economy.

In talking about present and future dialogues, the impact of technology must be part of the discussion. At the Library of Congress, the whole purpose of our investment in new technology is to affirm the importance of the book culture. It is important to ponder the possibilities of the digital revolution in light of previous technological revolutions’ impact on our modes of acquiring information, and communicating and sharing knowledge.

I strongly believe that one technological revolution never really cancels out the previous one. For example, manuscripts carried on long after books were introduced. In modern times, movies have not supplanted theatre, and radio is alive and well along with television.

Now, as we look to the future, how will new technologies co-exist with existing ones?