The Way We Were: Evolution of the Singapore Family

In conjunction with the launch of the exhibition “Roots: Tracing Family History”, held from 25 July 2013 to 16 February 2014, Kartini Saparudin ruminates on the question of families in Singapore.

At a local university, a sociology lecturer receives the following responses from her students to her question on what a typical Singapore family would look like: a nuclear family, with two children, plus a cat or a dog. Do these “educated perceptions” reflect the public imagination of the Singapore family? Or can families be imagined or constructed in other ways? By demystifying family and the “traditional family”, we see that most idealistic notions of family are far from what we might imagine. More significantly, an overemphasis on personal responsibility for strengthening family values encourages a way of thinking that leads to moralising rather than mobilising concrete reforms.1 Hence, examining families in the past allows us to see the relationship between families and public policies on families.

In this article, we explore how changing family structures in Singapore are a means of understanding Singapore’s history, identity formation as well as changing identities. There is no fixed definition of family as the concept is a social construct that varies across time and space. Yet, it is the most basic form of human organisation. Anthropologists have argued that all human societies are organised into some type of family. The universality of family is predicated upon certain characteristics that families are founded upon.

One basic human social experience is marriage. All known human societies have marriages as a legal, social and economic contract between a man and a woman or, until recently, two people of the same sex. Families are formed as a result of marriages. This union legitimises children born or brought into (through adoption) this union. Thus, we state the universality of family because marriage creates family. Family creates kin through firstly birth and descent and secondly through conjugality within the marriage institution and in-laws.

Families fulfil certain functions that enable a child to be fed, clothed and sheltered. The survival of the child is highly dependent on their family. Hence, families, through marriage, regulate sexuality and affect childbirth and childcare.

Marriage may not be a choice for everyone in modern industrial societies. The presence of state orphanages indicates that childcare is not necessarily familial. In addition, the changing status of women affects this as well. Same-sex union, cohabitation, single-parent households have introduced diversity to the traditional notion of family. Through this lens we can see how families have evolved, in particular, how “family” exists and has evolved in Singapore’s history.

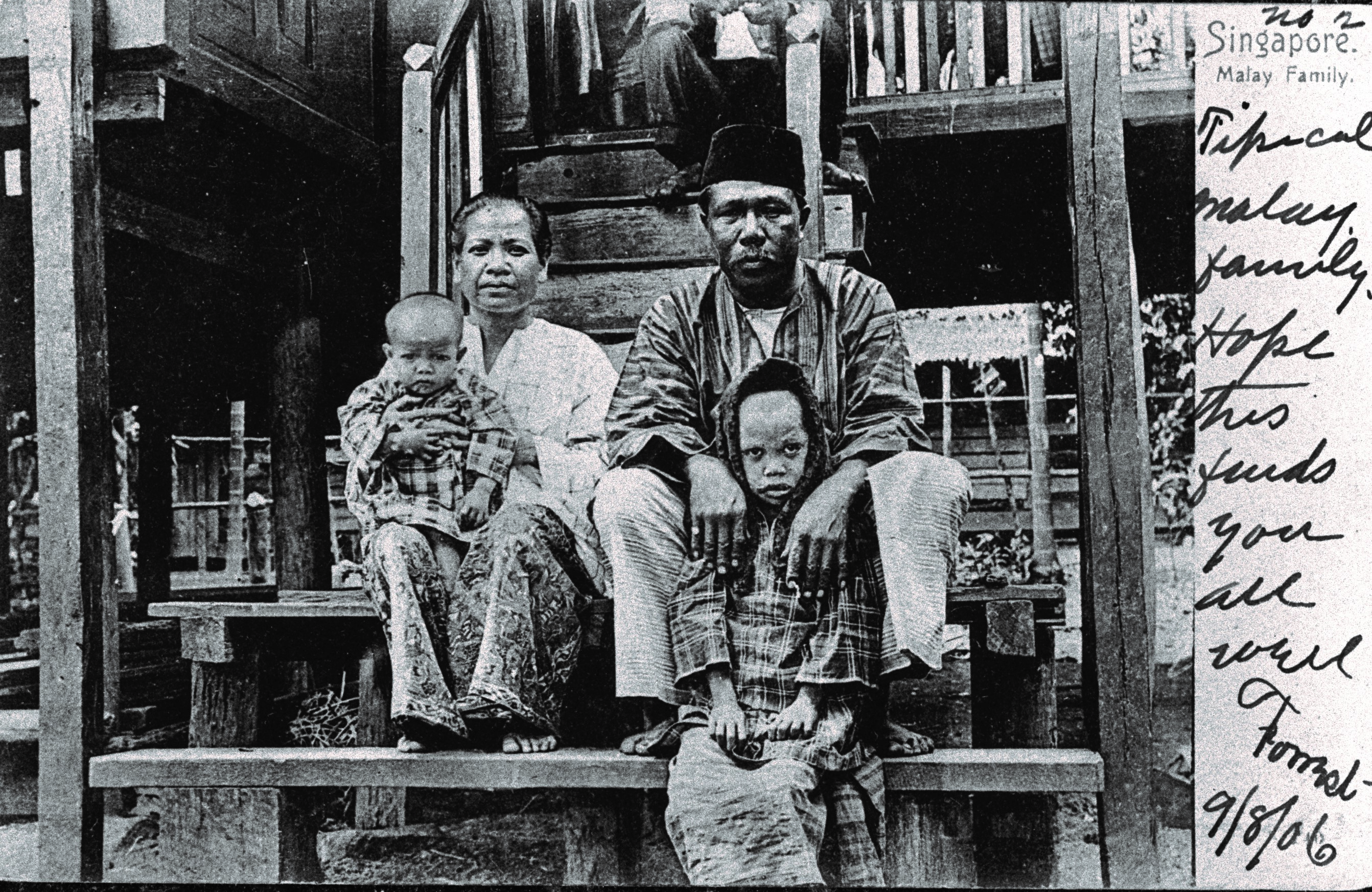

Impressions of Different Ethnic Families before 1820

Some former colonial writers have described ethnic families who were early settlers in Singapore. How typical or atypical they were of other ethnic families of that time remains to be answered. However, these general perceptions by colonial writers are useful starting points in the study of the different types of families that existed in early Singapore.

One of the earliest accounts of native families in Singapore relates to Malay royalty in the 17th century. In 1609, Johann Verken, a German officer of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) from Meissen (Germany) aboard one of the Dutch vessels under Admiral Peter Willemz Verhoeff, related:

“[Raja Bongsu] was in his appearance and body a well-proportioned

person, rather tall, softly spoken, and fair skinned both on his body and

his face. He had brought along with him thirty of his wives, which were of

different appearances, and dressed in very fine, colourful clothing.”2

Demonstrating the existence of polygamous unions of the royal family in the area, the relationship between wealth, power and the means to have big families is established. Furthermore, Raja Bongsu had wives “of different appearances”. This could indicate that they were of different ethnic backgrounds, groups, age or beauty. Apart from being a sign of prestige for the kings, the wives could have been part of exchanges between kingdoms.

The Malays, at this point, were a harder group of people to define. Linguistic and archaeological data suggest that people who could communicate in Old Malay and other Austronesian languages had “long possessed skills in pottery and weaving, as well as seafaring and the building of wooden canoes and houses; they grew rice and millet, kept pigs, used the bow and arrow and chewed betel”. They “possessed a bilateral kinship system, with corresponding prominence in the role of women and relative lack of concern about descent as distinct from group origins”.3 Mention of other groups of people and their families during this period is scant and few works mention anything beyond the existence of different types of traders and their trade.

Arrival of the British

With the “civilising mission” as justification for colonialism, the British took an anthropological approach in their task of documenting the lifestyles and cultures of the natives. Through such understanding, the colonials hoped to colonise the natives better, inviting as little opposition as possible to their rule. The British discovered many indigenous people living in the forests or on the sea such as the Semangs or the Orang Laut. Indigenous families tended to live in small groups and lived wherever there was food. This small nuclear family type enabled families to move to wherever the food was.4 The same could also be said about the Orang Laut (Sea People) – another group of indigenous people who lived in the area for centuries:5 “almost the whole of their life being spent upon the water in a wretched little canoe… A man and his wife and one or two children are usually to be found in these miserable sampans, for subsistence they depend on their success in fishing.”6

During this period, the British classified the Malays into two classes, the native and the foreign Malays. This division was more geographical than ethnographical. According to Frank Swettenham in British Malaya, the Malays are descendants of people who crossed from the south of India to Sumatra, mixed with a people already inhabiting that island, and gradually spread themselves over the most central and fertile states of Malaya. Foreign Malays came to Malaya from the borders of Kedah, Patani, Kelantan and the Southern Siamese states, including those from the seas – Acehnese, Javanese, Mandalings, Minangkabau, Palembang, Labuan, Borneo and Bugis. The native Malays are the descendants of the old Sumatran colonialists and intermarried with local aborigines and subsequent immigrants. There is an impression that the Malays live as part of the extended family:

“He never fails in respect towards his superiors. He has a proper

reverence for constituted authority… His domestic life is almost idyllic.

Towards his servants he is considerate and friendly… He is indulgent to

his wife, and perhaps even more so to his children, whom he generally

spoils. He supports his own relatives through thick and thin, but his sense

of charity does not take him beyond the family circle. He is content to live

in his own life in the bosom of his family like, a “frog beneath a coconut

shell [katak di bawah tempurung].”7

Intermarriages and Population Explosions Due to Immigration

Many low-ranking British officers who were posted to the Far East could not bring their families or women to the colonies as the colonial government was unwilling to pay for the maintenance of families. Eurasian communities such as Dutch Eurasians, Portuguese Eurasians and British Eurasians emerged as a result of intermarriages between these colonial servants and indigenous women. The Eurasian family type observed by John Turnbull Thomson comprised parents with many children, with servants living as part of the extended family, not different from Malay families.

“The head of the family was of mixed race, but educated in Europe. His

wife was of pure British blood, but was reared and educated in India. The

husband had children before his marriage by native women; his wife had

been married before, and had children by both her husbands. All lived

together in great amity in the same house… The family have long settled

in the country, held slaves prior to the abolition of slavery in the British

dominions. Some of the slaves still clung to the family. One of them, an

old woman, began to think of the advantage of creating a connection

with her mistress’s family.”8

Population began to increase rapidly with the great influx of immigration, despite severe measures adopted by the Dutch to prevent subjects from sailing to Singapore. It was believed that the new arrivals were mostly Malays while the rest were Chinese. It was not until the mid-1830s that the Chinese outnumbered the Malays.9 The sex ratios in the Chinese and Indian communities were disproportionate from 1824 to 1860 due to the increase in the number of predominantly male immigrants from China and India.

In his report on population trends in Singapore from 1819 to 1967, Saw Swee Hock wrote that “there is reason to believe that the women enumerated in the early censuses did not come direct from China but were mixed-blooded [Baba] women”. In addition, Charles Buckley mentioned that in 1837 “no Chinese women had come to Singapore and from China, and the newspapers said that, in fact, only two genuine Chinese women were … small-footed ladies, who had been some years before, exhibited in England”.10 Even J.D. Vaughn noted as late as 1876 that he knew of “no instance of a respectable Chinese woman emigrating with her husband”.11 This confirms that the Chinese men came to Singapore without bringing their wives. As temporary settlers, it was convenient to leave their wives and children in China. Furthermore, policies in China discouraged women from leaving in order to maintain ties with the overseas Chinese as well as to “ensure a flow of remittances from them”. It was only during the 20th century that a movement towards a more balanced sex ratio was observed. The relaxation of immigration laws during the 1880s and 1930s saw large-scale migration of female immigrants from China and India.12

Meanwhile, the disparity in the sex ratio among the Chinese created the Peranakan group.13 The Chinese who were born in Singapore tended to mix more with other ethnic groups and there was a trend “towards inter-ethnic marriages, especially between Chinese men and Malay women”. This was clearly reflected in the existence of a group called “Babas”. It was also likely that these unions were Sino-Orang Laut unions as observed by British colonial writers.

Hence, the Chinese female figure in the sex ratio that was reported by Saw is believed to be represented by Baba women. For the Chinese Peranakans during this period, the extended family was the norm.14

In the beginning of the 20th century, Chinese communities in Singapore and Malaya became more viable and self-sufficient. The Chinese tended to adhere more to their traditions and began to view “cultural mixing… as disruptive” but was tolerant of it as “it was an inevitable process that overseas Chinese communities had to undergo”.15 However, young Chinese girls were still seen as more desirable brides and hence the clans attempted to thwart the trend towards “Baba-isation”. Through frequent contacts with China, the clan would make suitable marriage arrangements between an overseas member and a China girl and also legalise overseas marriages. It was observed that “by doing so, the clans exercised considerable influence over the choice of spouses of its members, and prevented inter-dialect and inter-racial marriages from taking place”.16

For Indians during this period, however, intermarriages within the different Indian language groups and between Indians and other racial groups were even rarer. The Indians would return home to marry and leave their wives with their extended patrilineal families in India. Their lives in the region were focused on employment and trade. They would bring their wives and children to Singapore or Malaya when they had children, especially sons whom they wanted to educate in Malaya and Singapore.

Hence, as opposed to the Malays, Eurasians and the Chinese Peranakans who were part of large extended families, the Indians and Chinese migrants on the other hand who came from extended families in India and China respectively were forced to set up nuclear families as a result of migration.

Rise of Inter-ethnic Adoption

In the first half of the 20th century, the rate of population increase gained momentum to about 3 percent until the postwar period in 1947. The decade from 1947 to 1957 saw a return to the highest annual rate of increase at 4.5 percent since the 1840s. This could be attributed to factors such as a sharp fall in mortality rate, high fertility rate and large movements of people from Malaya to Singapore. By 1967, the Chinese sex ratio stood at 1,020 males per 1,000 females, which was more balanced than the Malay ratio of 1,045 and the Indian ratio of 1,684 males per 1,000 females. This prompted the formation of stable nuclear families among the Chinese and Indian communities.

Low use of contraceptives aided the high fertility rate of the 1930s. Child transfers and adoption were means of birth control for big families. Inter-ethnic adoption was a social phenomenon in 1930s Singapore and Malaya because of the existence of large settlements of Chinese, Malay and Indian families and, for some, the existence of harmonious inter-ethnic relations. The adoption process was conducted through informal means, that is, through direct contact between parents and foster parents and “child adoption brokers” such as doctors, nurses and midwives.

Especially dominant was the adoption of female Chinese babies in Malay and Indian ethnic communities. This phenomenon was peculiar to Southeast Asia where Chinese families were able to give their baby girls to other ethnic groups while an “assisted female mortality” was practised in China. Families in the Indian diaspora were willing to overlook the origin of a Chinese female baby more than an Indian baby due to caste expectations imposed upon those born Indian.17 Malay families, on the other hand, preferred adopting Chinese babies to Malay babies because of “no real danger that the true parents [would] later claim them back” and “the girls are fairer in complexion”.18 Official statistics could not reflect such inter-ethnic child transfers or adoption despite the institution of the Adoption Act of 1949 and the Children and Young People Ordinance of 1950 because there was no legal obligation to register the transfer of a child.19

This trend of inter-ethnic adoption and child transfers indicated that nuclear families were big. As mentioned, adoption and child transfers were means of birth control for big, poor families, especially for families that preferred sons. This “big family” type was to undergo another change during the postcolonial period.

Postcolonial Era: Industrialising the Family

During the postcolonial period, conditions such as poor sanitation, health issues and fires – specifically the Bukit Ho Swee fire – provided an intimate link between marriage, gender, family and housing.20 Family types were particularly influenced by government policies on public housing. The provision of public housing by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) for nuclear families was in part ideological as it put an end to the existence of kampongs (villages) or squatters, which were believed to be hotbeds of communism and communalist propaganda. In the first decade of its existence, the HDB built 106,000 units and the percentage of Singapore’s population housed in HDB flats rose from 9 percent to 32 percent.

With the passing of the Women’s Charter in 1961, monogamy was the only legal marriage practice recognised by the state.21 Muslims were an exception since they were governed by Shariah Law. Thus began the creation of the nuclear families in the 1960s and 1970s in tandem with birth control policies formulated during that period.

In the early years of Singapore’s independence, the government was faced with the formidable task of providing education, health services and housing to a population that was growing rapidly due to the postwar economic boom. Family planning was thus regarded as a necessary measure for the government to adequately tackle issues arising from planning for the national economy to welfare services for citizens.22

The objective of the Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, formed in 1966, was to exhort families to plan for smaller families. Its campaigns were aimed at less educated and lower-income groups, encouraging them to have only two children so that their offspring would stand a better chance in life.23 The benefits of a small family were widely publicised through 35,000 posters and 100,000 leaflets, as well as a range of other publicity efforts.24

This anti-natalist stance was taken to encourage more women to join the workforce in order to increase the manpower needed for Singapore’s industrialisation needs. The birth control policies were so effective that the birth rate declined from 6.55 births per woman in 1947 to 4.62 in 1965 to 1.7 in 1992.25 With the two-child message entrenched, the family programme proceeded to focus its efforts on encouraging wider intervals between each birth, and dissuading young people from early marriage and parenthood.26

The population control efforts were a resounding success, but by the late 1980s, Singapore’s falling birth rate had become a cause for concern.27 This decline was further propelled by a trend among young and educated Singaporeans to delay marriage and children in order to establish a stable career. Former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew felt that the drop in the birth rate among the well educated would cause a “thinning of the gene pool”. Lee felt that better-educated women should be mothers. He cited the 1980 census showing women with secondary or tertiary education were having an average of 1.65 children, compared with uneducated women who were having three children on average.

Subsequent discussions that resulted from this issue pertained to the increasing number of unmarried women with tertiary education and the lower reproduction rate of the Chinese, particularly those with higher education.28 This is still cause for concern today because of the perceived loss of talent due to the eugenics policy, a reduced labour force and an increasing proportion of aged dependents in the country. To avoid the implications of a rapidly ageing population, the state implemented a slew of measures to reverse this trend by encouraging procreation through measures such as Baby Bonuses and “opening the economy” to talent from China, India and the Philippines.

Declining Marriages and Increasing Trend of One-Child Families

Statistics reveal that the image of an ideal family consisting of two parents and two children is no longer representative. In sum, the absolute number of marriages has declined by 1,718 – from 26,081 in 2009 to 24,363 in 2010. This is a reverse in trend, as there was an increase in the absolute number of marriages yearly from 2005 to 2009. General marriage rates continue to decline and single-child families are an increasing trend. This departs from popular perceptions that the average family has 2.1 children.

Among ever-married females aged 40 to 49 years who were likely to have had children, the proportion with one child increased from 15 percent in 2000 to 19 percent in 2010, while those who were childless increased from 6.4 percent to 9.3 percent. With more ever-married females having one child or remaining childless, the average number of children born to resident ever-married females declined for most age groups. This has further consequence as there was also a delay in childbearing. While peak fertility rates among women were in the age group of 25 to 29 years in 2000, it has since shifted towards the 30 to 34 years age group from 2002 onwards.

The number of divorces has also been rising, although at a more moderate pace in the last five years. Divorces and annulments increased by 19 cases from 7,386 in 2009 to 7,405 in 2010, a smaller increase compared to the increase of 170 cases from 2008 to 2009.

Shrinking Household Sizes and Dual-Income Families

With falling birth rates, household sizes in Singapore have declined over the past 30 years from an average of 4.2 persons in 1990 to 3.5 in 2010. Figures indicate that Singaporeans may have less immediate family support as fewer members are staying in the same household to provide care for young children and the elderly.29

In terms of working status, the proportion of married couples where both husband and wife work accounted for 47 percent in 2010, up from 41 percent in 2000. The traditional arrangement where only the husband worked was less prevalent, with the proportion declining from 40 percent in 2000 to 33 percent in 2010. With the increase of married women entering the workforce, work-life balance could be an increasing challenge for husbands and wives to negotiate as they juggle work, marriage and household demands.

Conclusion

The functionalist approach in state policy influences the role and types of families in Singapore. There is now a greater reliance on the family especially with the demands of an ageing population in a non-welfare state like Singapore’s. The state’s recommendation of an intergenerational three-tiered family in the 1980s was scrapped as more and more children lived apart from their parents. The HDB’s Sample Household Survey in 2008 showed a decline in the proportion of younger married children who preferred to live with their parents or within close proximity of them.

In addition, current opposition to Section 377a of the Penal Code, which criminalises sex between two consenting men, further pushes the boundaries of how the state defines families. How this would impact state definitions of family remains to be seen. It can be said that it will be a long time before the state accepts differing definitions of family. In the eyes of the state, the family has to be reliant and stable and alternative family models such as singles, same-sex couples and cohabiting couples are seen as a challenge to the state’s view of stable families.

We need to develop a clearer sense of how past families actually functioned and what the consequences of family values and behaviours have been. In sum, “Good history and responsible social policy would help people incorporate the full complexity and tradeoffs and family change into their analyses and thus into action. Mythmaking does not accomplish this end.”30

This article was reviewed by Senior Lecturer Saroja Dorairajoo, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore.

REFERENCES

Barnard, T.P. (2007, December). Celates, Rayat-Laut, Pirates: The Orang Laut and their decline in history. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 80 (2) (293), 33–49. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Borschberg, P. (2011). Hugo Grotius, the Portuguese and free trade in the East Indies. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSEA 341 BOR)

Cartwright, H.A., & Wright, A. (Eds.). (1989). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources. Singapore: Graham Brash Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 TWE)

Chua, B.H. (1994). Private ownership of public housing in Singapore. Australia: National Library of Australia. (Call no.: RCLOS q363.585 CHU)

Clifford, H.C. (1897). In court & kampong: Being tales and sketches of native life in the Malay Peninsula. London: G. Richards. Retrieved from BookSG.

Cook, J.A.B. (1907). Sunny Singapore: An account of the place and its people, with a sketch of the results of missionary work. London: Elliot Stock. Retrieved from BookSG.

Coontz, S. (2000). The way we never were: American families and nostalgia trap. New York, NY: Basic Books. (Call no.: R 306.85 COO)

Djamour, J. (1965). Malay kinship and marriage in Singapore. London: Athlone Press: Humanitarian Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.42095957 DJA)

Freedman, M. (1957). Chinese family and marriage in Singapore. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. (Call no.: RSING 301.42 FRE)

Frost, M.R. (2003, August). Transcultural diaspora: The Straits Chinese in Singapore, 1819–1918 [Asian Research Institute Working Paper Series No. 10]. Retrieved from nus.edu.sg. website.

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1969, July). The Orang Laut of Singapore River and the Sampan Panjang. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 42 (1), 118–132. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Lyons, L. (2004). A state of ambivalence: The feminist movement in Singapore. Leiden: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 LYO)

Makeswary, P. (2007, October). Indian migration into Malaya and Singapore during the British Period. BiblioAsia, 3 (3). 4–11. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website.

Marsden, W. (1812). A dictionary of the Malayan language, in two parts, Malayan and English, and English and Malayan. London: Cox and Baylis. Retrieved from BookSG.

Milner, A. (2008). The Malays. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. (Call no.: R 305.89928 MIL)

Ng, B. (1983, August 15). Get hitched! And don’t stop at one. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Robson, J.H.M. (1894). People in native state. London: Makepeace. Retrieved from BookSG.

Saw, S.W. (1969, March). Population trends in Singapore, 1819–1967. Journal of Southeast Asian History, 10 (1), 36–49. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2018, May 9). Census of population 2010. Statistical release 2: Households and housing. Retrieved from Singstat.gov.sg website.

Singapore Family Planning and Population Board. (1975). Annual report. Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 301.426 SFPPBA)

Singapore. Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports; National Family Council (Singapore). (2011). State of the family report 2011. Singapore: National Family Council and Ministrty of Community Development, Youth and Sports. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Stoler, A. (2010). Carnal knowledge and imperial power: Race and the intimate in colonial rule. California, Berkeley: University of California Press. (Call no.: R 305.8 STO)

Thomson, J.T. (1865). Some glimpses into life in the Far East. London: Richardson & Co. Retrieved from BookSG.

Tibbetts, G.R. (1957). Early Muslim traders in South-East Asia. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 30 (1), (177), 1–45. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Yen, C.H. (1981, March). Early Chinese clan organizations in Singapore and Malaya, 1819–1911. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia, 12 (1), 62–92. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

NOTES

-

Borschberg, 2011, p. 258. ↩

-

Barnard, 2012. ↩

-

Gibson, 1969, p. 119. ↩

-

Cartwright & Wright, 1989, p. 132. ↩

-

Saw, 1969, p. 38. ↩

-

Saw, 1965, p. 43. ↩

-

Saw, 1965, p. 450. ↩

-

Yen, Mar 1981, p. 84. ↩

-

Wee, 1977, p. 294. ↩

-

Freedman, 1957, p. 121. Freedman notes that polygamy was common among the rich Chinese without giving a figure, whereas Djamour notes that polygamy marriages were less than 1 percent of Muslim marriages. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 1 Nov 1960, p. 1. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 20 Jul 1972. ↩

-

Annual report, 1973, p .49. ↩

-

Annual report, 1975, p. 49. ↩

-

Wong & Yeoh, 2003, pp. 11–12. ↩

-

State of the Family Report 2011; Census of Population 2010, Statistical Release 2: Households and Housing. ↩