Into the Melting Pot: Food As Culture

Through the lens of the unique Lunar New Year creation, yu sheng, find out how the simplest dishes can be canvases upon which cultural and national identities are inscribed.

According to Chinese folklore, the four corners of the sky collapsed upon itself after a fierce battle between the gods of water and fire. The Chinese Goddess Nuwa tempered five-coloured stones to mend the sky, then cut off the feet of a great but luckless turtle, whose formidable appendages were used as struts to hold up the firmament.

Her work done, Nuwa grew restless and a little lonely, so on the first day, she created chickens to keep her company. On the second day, she created dogs, followed by sheep on the third, pigs on the fourth, cows on the fifth and horses on the sixth. On the seventh day, Nuwa folded up the sleeves of her robes and fashioned human beings from yellow clay, sculpting each one carefully. She was fatigued – and a little impatient – after creating hundreds of such figures in this manner, so she dipped a rope in the clay and flicked it such that blobs of clay landed everywhere. The handcrafted figures became nobles, while the blobs turned into commoners.

This seventh day falls on zhengyue, the first month of the Chinese calendar and is known as renri (literally Human Day) – the birthday of mankind. Renri also coincides with the seventh day of the Chinese Lunar New Year.

On renri, Singaporeans and Malaysians of Chinese descent celebrate their universal birthday by eating yu sheng – more popularly known as yee sang in Malaysia – a peculiarly local practice of eating raw-fish salad (see text box below) with a history that can be traced back to the 1960s.

A Lucky Dish of Fish

Fortune or luck is a great arbiter in Chinese culture, and the Chinese are unabashed in their pointed preference for material wealth. The longing for instant prosperity and wealth is underscored in the lo hei exercise, with its broad tossing and sweeping gestures.

One of Singapore’s most renowned cooks, Chef Sin Leong, recalled how upset his diners were when in the early days the dish of yu sheng was tossed by the chefs in the kitchen before it was served. “They said we were taking away their good fortune, so they would rather toss it themselves!”

The performative ritual of ushering in wealth is only symbolic; more importantly, eating in ritual contexts can also reaffirm relationships with others.1 The communal partaking of yu sheng is perhaps the closest thing that the Chinese, known for their usually reserved nature, ever come to “dancing like no one is watching” as a family over food.

Food as a Form of Culture

The Department of Anthropology at Oregon State University defines culture as “learned patterns of behaviour and thought that help a group adapt to its surroundings”.2 Culinary culture is central to diasporic identification, with the focus on the place of food in society, specifically in the enduring habits, rituals and daily practices that are collectively used to create and sustain a shared sense of cultural identity.

To this end, restaurateur, chef and F&B consultant, David Yip, hopes to reinvigorate cultural identity across the Chinese dialect groups in Singapore with his epicurean club, Jumping Tables, a sporadic and informal culinary gathering that features respected chefs whipping up time-honoured recipes the traditional way. Yip invites a number of chefs – from humble eateries to established restaurants – to cook at these gatherings.

One of the chefs Yip was most eager to feature at Jumping Tables was Chef Sin Leong, one of the founding chefs of the Red Star restaurant on Chin Swee Road and owner of the now-defunct Sin Leong Restaurant, a local institution of Cantonese cuisine that opened in 1971. When Sin, 86, agreed to participate in Jumping Tables, Yip and his guests could barely contain their excitement.

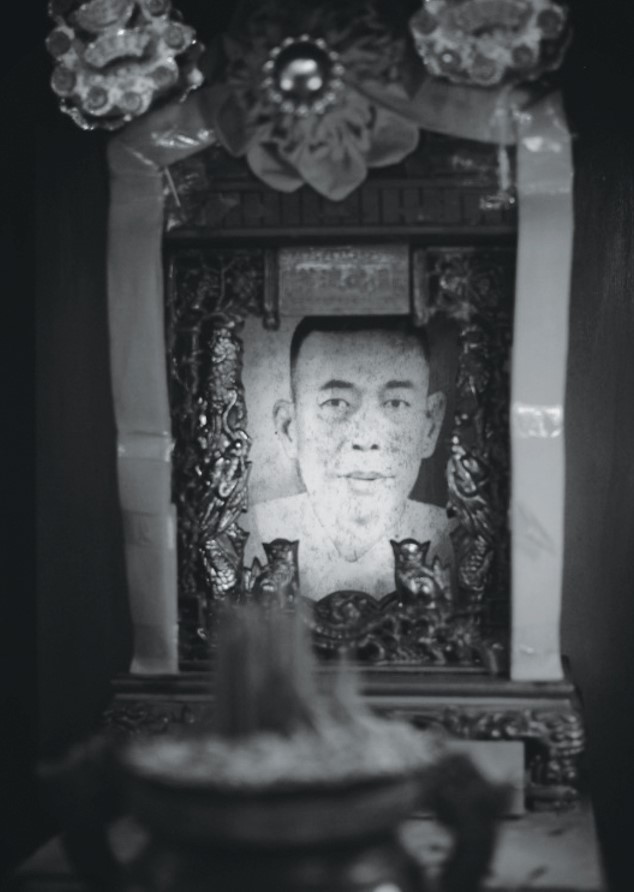

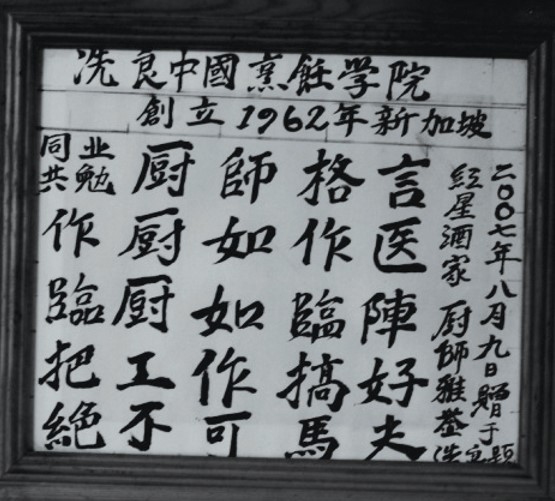

Before the meal commenced, Chef Sin insisted that the guests visit the altar in his kitchen, where his mentor, the late Master Luo Cheng, smiles from an ornate frame, amid offerings of orchid blooms and clouds of incense. Hailing from Shanghai, China, Master Luo had groomed Singapore’s four most prominent Chinese chefs in the 1970s. His protégés – Sin Leong, Hooi Kok Wai, Tham Yui Kai and Lau Yoke Pui – were later crowned as Singapore’s “Four Heavenly Culinary Kings”.

Under the tutelage of Master Luo, the four young junior chefs toiled in the kitchen under his stern eye and exacting standards at the famed Cathay Restaurant in the old Cathay Building. Opened in 1940, it initially served European fare, but underwent a revamp in 1951 under Master Luo to become the finest Chinese restaurant in Singapore, specialising in Cantonese cuisine. Cathay Restaurant closed in December 1964 and reopened under a new management in the renovated Cathay Building in 2007.

Chef Hooi, the founder of the famed Dragon Phoenix restaurant – located today in Novotel Clarke Quay on River Valley Road – remembered Master Luo as being very strict, not only making them sharpen their culinary skills but also inculcating in them good work ethics. “[Master Luo] believed that besides skills, good chefs must be equipped with a high standard of social responsibility because they feed so many people,” Hooi shared. Once the four apprentices had attained a certain level of culinary proficiency, Master Luo told them to go forth to spread the art of Cantonese cuisine.

The four took their teacher’s word seriously and each opened a restaurant: Sin opened Sin Leong Restaurant, Hoi started Dragon Phoenix, Tham established Lai Wah restaurant (on Bendemeer Road) and Lau launched Red Star. The four decided it was important that their restaurants did not cannibalise one another’s menus. Each would have their own signature dishes. “They were like brothers,” said Chris Hooi, the son of Chef Hooi, who now helms Dragon Phoenix. This bond was no doubt forged through their years of slaving over hot stoves together in the kitchen.

Beyond this, the four decided they would meet every week to discuss fresh ideas for new recipes. These gastronomic brainstorming sessions resulted in iconic Singaporean dishes such as the chilli crab and deep-fried yam ring as well as the modern version of yu sheng.

Master Luo’s fervent wish to extend the popularity of Cantonese cuisine and his four apprentices’ desire to execute this wish were almost evangelical in intent. Singapore’s early immigrants were motivated by pride and desire to revalidate their racial and cultural identities, as well as those of generations to come, despite being physically far removed from their motherland. When examined through the lens of the early immigrants, Master Luo’s zeal for his native Cantonese cuisine can be better understood. For Luo and his protégés, it was likely that the preparation, cooking and serving of Cantonese cuisine became the nexus of their diasporic Chinese identity.

Mankekar argues, much in the same vein, that Indian customers do not visit ethnic markets in the Bay Area in San Francisco merely to shop for groceries, but to engage with representations of their (sometimes imagined) homeland.3

Invented Traditions and Nationalism

People from the province of Canton (Guangdong) have been eating raw fish with sliced ginger and spring onions drizzled in lime as a porridge accompaniment since the 1920s. When these Cantonese immigrants brought their cuisine over to Singapore, changes were made to the original recipe. Perhaps the changes – embellishing the plain slivers of fish with creative additions such as fried dough crisps and plum sauce – were a result of the immigrants’ exposure to the cuisine of their newly adopted home.

In 2012, a minor tussle over who rightfully invented yu sheng broke out when a professor from Singapore had offhandedly suggested on a social media platform that yu sheng, among other intangible practices such as Singlish, belonged to the UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.4 The list, which includes traditional social practices, rituals and festivals passed on from one generation to another, was established by UNESCO to help countries protect and preserve their heritage.

Singaporeans claimed that yu sheng had been invented by the “Four Heavenly Culinary Kings” in 1963, debuting at Dragon Phoenix and Lai Wah during the Lunar New Year of 1964. Chef Hooi recalled, “[We] concocted a unique sweet-sour sauce, added crushed peanuts and sesame seeds to the fish (inspired by a local salad called rojak), and assembled other colourful ingredients to symbolise prosperity in Chinese culture. To make the carrot strips thinner, I purchased the first rotating carrot shredder at Tangs on Orchard Road.”

On the other hand, Malaysians insisted that yu sheng had originated in a restaurant in Seremban, in the state of Negeri Sembilan. The national papers each weighed in with their own “food experts”, with the Malaysian national broadsheet The Star concluding that the dish had originated in Malaysia, but was better promoted in Singapore.

Previous food fights between Singapore and Malaysia had taken place in 2009, when Malaysian Tourism Minister Datuk Seri Dr Ng Yen Yen claimed that bak kut teh (a herbal pork rib soup) and Hainanese chicken rice, among other dishes, were authentically Malaysian, drawing the ire of many Singaporeans.5

Malaysians and Singaporeans are certainly not alone in claiming authorship of famous dishes. The sticky sweet baklava, for instance, is claimed by more ethnic groups than yu sheng: Greeks, Turkish, Iranians, Bulgarians, Uzbeks, and even the Chinese all claim to have created it.6 The pastry, filled with chopped nuts and sweetened with syrup, has been the subject of fierce nationalist debates involving passionate Greek-Cypriot baklava makers to the Turkish State Minister.7

As food often plays a major role in the construction of national identities, food fights of the sort described here may point to an already shaky national identity. Wilk’s analysis8 of the rise of Belizean cuisine in the Central American state emphasises that “both nation and cuisine are more intrinsically imagined than in most contexts”. Belizean cuisine – with dishes like escabeche (onion soup) and panades (fried maize shells with beans or fish) – was developed in response to the perceived need for a culture of nationhood after independence in 1981. In his analysis, Wilk contrasts bland, imported meals of the 1970s with Belizean “local food” of the 1990s, where the latter performed the role of “an important imagined tradition of Belizean authenticity”.

The periodic tussles between Singapore and Malaysia over the origins of their “national dishes” perhaps underscore the latent anxiety that exists between the two countries over who is the rightful owner of certain dishes – and by extension the progenitor of their associated food culture. Singapore and Malaysia were first brought together as Malaya under British rule from 1824 (after the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty) to 1957, followed by their short-lived merger from 1963 to 1965. Hence, it is easy to concede that there would be organic similarities in the preparation and evolution of the transplanted cuisines of early migrants over the years. But there is more to the issue than meets the eye.

Beyond specific nationalist and ethnic anxieties, perhaps another primary distinction to make of the yu sheng-lo hei conundrum is one of etymology versus semiotics: Is the tussle over yu sheng – the dish of raw-fish salad and its constituents, variations of which had long been in existence in China’s Canton province – or is it over lo hei – the performative ritual of tossing slivers of raw fish and its accompaniments in a communal social setting? Where does one end and the other begin?

The Gastronomic Memory of Diaspora

In a nation that has often been accused – by foreigners and locals – of not having a strong local culture, questions on how and what we eat, as well as when and by whom our national dishes were invented can be particularly pressing. The city-state is after all marketed by the Singapore Tourism Board to the world as a food and shopping haven. Singapore’s latest tourism tagline is “Shiok!”9, a succinct Singlish term that translates loosely to “extreme pleasure”, derived from syok the Malay word for “nice”.

If food can legitimately be positioned as culture, then Singaporeans are certainly not bereft of it; in fact, the culture of food defines its people. Calvin Trillin in The New Yorker said, “Culinarily, [Singaporeans] are among the most home sick people I have ever met.”10 Singapore has been built on the backs of migrants who each brought their bloodlines, languages, customs and signature dishes into a melting pot of cultures, yet still maintaining their own individual ethnic identities – articulated most clearly through food. This is why perhaps dishes like yu sheng, which have clear cultural roots as well as rituals that bring together extended families in a salute of chopsticks, can be viewed as true emblems of food culture and heritage.

In this mutating world, Singaporeans need to cultivate concern about their food heritage: how did dishes thought to be unique to the Singapore experience evolve? Who invented them and when? We should not be satisfied with the mere gustatory act of eating a delectable dish of rojak (fruits and vegetables tossed in prawn paste) or char kway teow (fried rice noodles in dark, sweet sauce). For it is in dishes such as yu sheng, meticulously prepared, served and performed by specific communities – even while revamped with new ingredients for a contemporary palate – that the trauma, exile and nostalgia of the diasporic communities11 are both ingested and externalised.

Food comes to Singaporeans naturally: we are passionate about it, we join snaking queues for ambrosial laksa (noodles in spicy coconut broth), we seek out obscure corners of the island for the best fish-head curry, and our conversations are frequently peppered with musings about all things related to food.

Casting an anthropological lens on the food we enjoy allows us to understand ourselves more deeply even as our eyes sweep over chilli crab, chendol and mee rebus. What we are consuming is not just crustacean and chillies, coconut milk and palm sugar, or noodles with piquant gravy, but unwritten parts of the histories of our diasporas, hidden in the woven intricacy of a ketupat (Malay rice cake), the folds of a zongzi (Chinese dumpling) and the artful blend of spices in a curry, passed down through generations in recipes and memory-laden flavours. And when we bend our heads to eat, we suddenly realise that we are drinking from the bowl of our culture’s belly.

The Art of Yu Sheng

Typically, diners gather around a large platter filled with slivers of raw fish, usually ikan parang (wolf herring), shredded green and white radish and carrot, pickled ginger, pomelo segments, chopped peanuts, deep-fried flour crisps and sesame seeds, among other ingredients. Someone usually takes the lead, calling out certain auspicious phrases in Mandarin – all of which invariably invoke wealth and long life – as the various ingredients and dressings (including pepper, plum sauce and oil) are thrown into the mix. Then all hell breaks loose.

Amid raucous cries of lo hei – a Cantonese term referring to the action of lifting one’s chopsticks and tossing the raw-fish salad – diners dig into the dish, raising their chopsticks as high as they can and mixing the ingredients while trying to keep everything on the plate.

In Chinese culinary symbolism, 鱼 (yu; fish) is frequently conflated with its homophone, 裕 (yu), meaning “abundance”, whilst 生 (sheng; raw) can be taken as its homophone 升 (sheng), meaning “to rise”. When coupled, yu sheng is a symbol of a rise in abundance – be it prosperity, vigour, personal growth or happiness.

Like a layered Tang-dynasty poem where each noun is a palimpsest for something more pertinent, many Chinese dishes and their ingredients are specially selected for their ability to engender good fortune. Even the humble deep-fried bits, in the hue and shape of “golden pillows”, belie a greater hope of 满地黄金 man di huang jin, that is, floors full of gold. Traditionally, the addition of each ingredient to yu sheng is accompanied by the recitation of a specific 成语 (cheng yu), a four-character idiom.

Yu sheng is not for the shy and retiring. The partaking of the dish is as much about the ritual as the consumption. During the ensuing melee, diners may find themselves losing a chopstick, pelted in the eye by a peanut shrapnel or, worse, have their new clothes stained by plum sauce.

Yu sheng has become a Lunar New Year staple and so popular that restaurants in Singapore serve it throughout the 15-day Lunar New Year period, not just on the seventh day. In the spirit of gastronomic creativity (and conspicuous consumption), the traditional translucent slivers of ikan parang may also be replaced with salmon, lobster or abalone.

REFERENCES

Holtzman, J.D. (2006). Food and memory. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 361–378. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Kalimniou, D. (2006, June 6). Political Kouzina. Retrieved from diatribe-column.blogspot.sg website.

Let’s Yee Sang for another round of food fight. (2012, January 30). The Star. Retrieved from Thestar.com website.

Mankekar, P. (2002). India shopping: Indian grocery stores and transnational configuration of belonging. Ethnos, 67 (1), 75–97. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website.

Mints, S.W., & Du Bois, C.M. (2002). The anthropology of food and eating. Annual review of Anthropology, 31, 99–119. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Oregon State University. (2012, December 26). Definitions of anthropological terms. Retrieved from oregonstate.edu website.

Safran, W. (1991, Spring). Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, 1 (1), 83–99. Retrieved from UTP Journals website.

Singapore Tourism Board. (n.d.). Faces of Singapore. Retrieved from visitsingapore.com website.

Trillin, C. (2007, September 3). Singapore journal: Three chopsticks. The New Yorker, p. 48. Retrieved from New Yorker.com website.

Wilk, R.R. (1999, June). Real Belizean food: Building local identity in the transnational Caribbean. American Anthropologist, 101 (2), 244–255. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Yong, N. (2013, April 28). Singapore shiok, or just silly? The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Mints, S.W., & Du Bois, C.M. (2002). The anthropology of food and eating. Annual review of Anthropology, 31, 99–119. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Oregon State University. (2012, December 26). Definitions of anthropological terms. Retrieved from oregonstate.edu website. ↩

-

Mankekar, P. (2002). India shopping: Indian grocery stores and transnational configuration of belonging. Ethnos, 67 (1), 75–97. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website. ↩

-

Let’s Yee Sang for another round of food fight. (2012, January 30). The Star. Retrieved from Thestar.com website. ↩

-

The Star, 30 Jan 2012. ↩

-

Holtzman, J.D. (2006). Food and memory. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 361–378. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Kalimniou, D. (2006, June 6). Political Kouzina. Retrieved from diatribe-column.blogspot.sg website. ↩

-

Wilk, R.R. (1999, June). Real Belizean food: Building local identity in the transnational Caribbean. American Anthropologist, 101 (2), 244–255. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Yong, N. (2013, April 28). Singapore shiok, or just silly? The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Trillin, C. (2007, September 3). Singapore journal: Three chopsticks. The New Yorker. Retrieved from New Yorker.com website. ↩

-

Safran, W. (1991, Spring). Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, 1 (1), 83–89. ↩