Singapore Comics Showcase

Find out how prejudiced attitudes towards comics changed when a series of educational comics became bestsellers.

On 31 August 1960, The Singapore Free Press ran an article with a rather controversial headline: “Bad boys … comics to blame, say the teachers.” Some 58 teachers from English schools had met at a closed-door meeting to debate the supposedly ill effects of comics on teenagers. After six long hours, the meeting concluded that comics were a form of “misguided culture” that contributed to juvenile delinquency in Singapore. The declaration was part of the government’s decade-long campaign against “yellow culture” – a movement against Western decadence, pornography and gangsterism – that had been launched the previous year.

Thankfully, such prejudiced attitudes towards comics changed in the early 1990s when a series of educational comics published by Asiapac Books became bestsellers. Public libraries, too, recognised this popular art form: in 1999, graphic novels were added to the collection of the former library@orchard in Ngee Ann City. In the same year, a small exhibition showcasing local political cartoons by Tan Huay Peng and Morgan Chua was held in the courtyard of the old National Library on Stamford Road.

From May to June 2013, the 24 Hour Comics Day Showcase was held at various public library branches such as Sengkang and Serangoon. This exhibition featured the works of young artists who participated in the 2011 and 2012 editions of 24 Hour Comics Day.

In conjunction with the Singapore Memory Project, Chinese newspaper Lianhe Zaobao has organised an exhibition, “A Collection of Our Shared Memories”, showcasing 90 years of comics published in the broadsheet in celebration of its 90th anniversary. From August to November 2013, the exhibition travelled from the National Library on Victoria Street to library@chinatown to Woodlands Regional Library and to its final stop at the SPH News Centre.

The “24 Hours Comics Day” Nationalism

24 Hour Comics Day started in the United States in 2004 to encourage aspiring artists to create 24 pages of comics in 24 hours. Participants gather for a full 24-hour period to complete a 24-page comic. The event gives free rein to their imagination. It has since been adopted by countries across the world. The first 24 Hour Comics Day in Singapore was in 2010, and on 20 October 2012, the third edition was held at Bukit Merah Public Library.

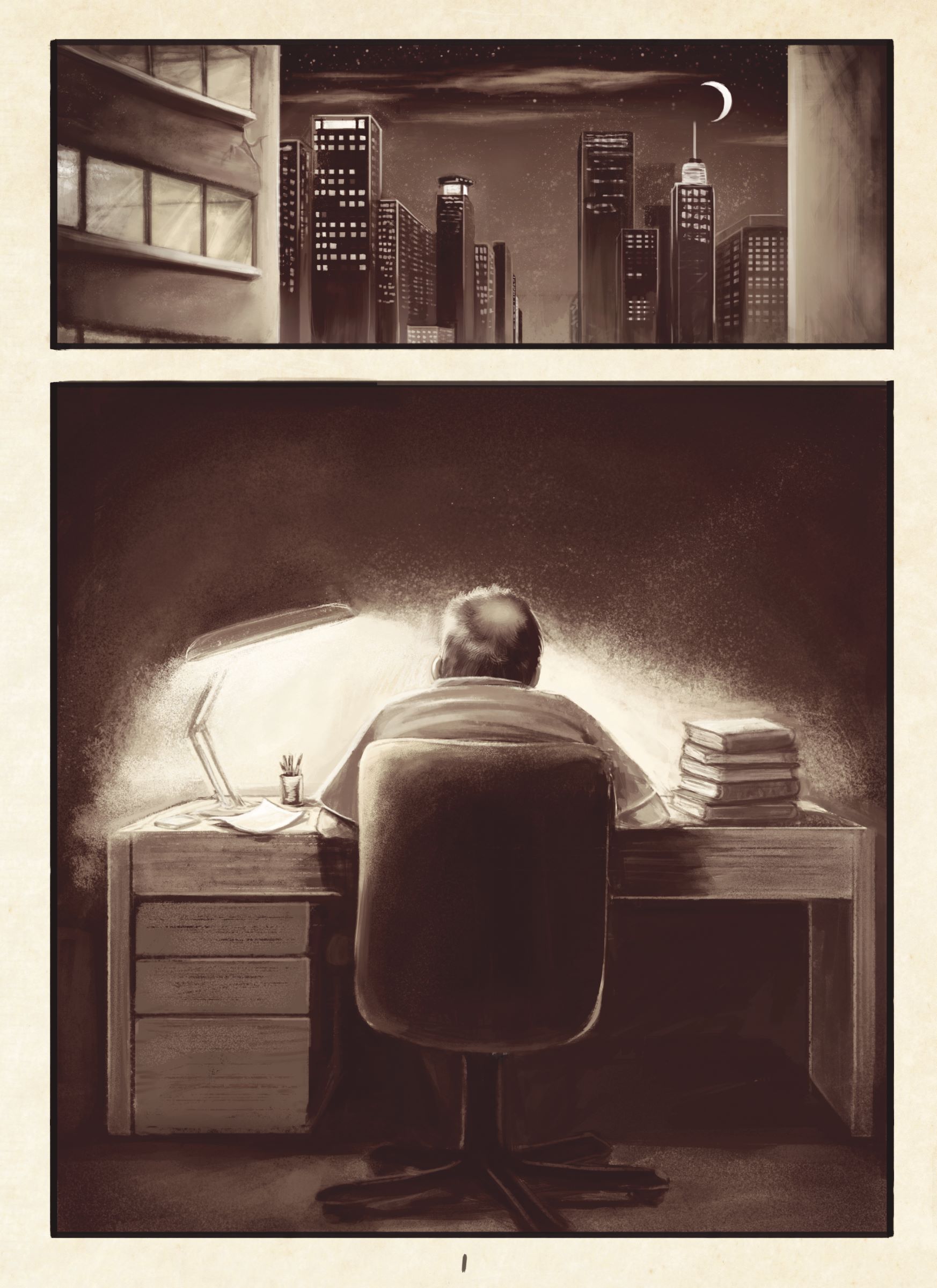

The 24 Hour Comics Day Showcase in 2013 featured a total of 15 works, many of which were centred on the theme of pursuing one’s dreams. In Changing Stories, Christal Kuna recounts a wordless but poignant coming-of-age story about life choices and a father’s love and guidance. Max Loh’s The Road Not Taken references Robert Frost’s inspirational poem of the same name, recounting the personal story of his decision to study the sciences and how, as an adult now, he is drawing comics in his free time. Jerry Teo adapted Aesop’s didactic fable, The Dog and the Wolf, questioning whether it is better to live comfortably and be subjected to a human master, or to live freely and be the master of one’s own destiny. Dog and Wolf was voted by participating artists as the best story created at the 2012 event.

Participants also used the opportunity to create comics that express their opinions about social issues. For instance, Japanese art director Emiko Iwasaki’s anger is palpable in her story, Wish, which documents the discrimination and sexual harassment faced by women in Japan.

Wish is one of many autobiographical comics created at the Comics Day event. This genre is a recurrent one among many artists in America and has its Southeast Asian counterparts among Indonesian artists such as Tita Larasati and Sheila Rooswitha. Local artists who have adopted this genre include Koh Hong Teng and Troy Chin. In a similar autobiographical vein, albeit more lighthearted style, is Hanse Kew’s Bundle of Joy, a story about his journey to fatherhood.

Other past works include humour strips, such as Clio Ding’s Kevin and Magical Nonsense (2011), and adventure stories such as Benjamin Chee’s Gate of Joy (2012), which are influenced by the Japanese manga and anime style of cartoons. Many of the artists are still developing and finding their own voices and it is encouraging to see these talents bravely exploring their creativity in public.

A Collection of Our Shared Memories

In 1923 and 1929 respectively, Chinese-language newspapers Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh were founded. In 1983, they merged to form Lianhe Zaobao. This year, Lianhe Zaobao celebrates 90 years of Chinese newspaper publishing in Singapore with the exhibition, “A Collection of Our Shared Memories”, supported by the Singapore Memory Project. It traces 90 years of cartoons published in these newspapers.

These cartoons serve as mirrors of our times, their subject matter revolving around everyday issues such as food, work, housing and transport, reflecting the sociopolitical changes in Singapore. In the 1920s and 1930s, most of the cartoons in Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh focused on China, which was not surprising as many of the artists as well as the editor of Sin Kwang (the pictorial supplement of Sin Chew Jit Poh), Tchang Ju Chi, were Chinese migrants. The newspapers served as a news link between the Chinese immigrants in Singapore – most of whom were sojourners and did not intend to settle down – and their homeland.

In the 1930s, the cartoons began to cover more local topics and issues. This can be attributed to the editorship of Dai Yinglang at Wenman Gie (World of Literature and Cartoons), the arts supplement of Nanyang Siang Pau. Dai wanted the cartoons to document the lives of the locals, especially the poor. Influenced by the Chinese writer, Lu Xun, he believed that art should serve the people and that it could spark radical changes in thinking and in society. These works marked the early signs of discontentment with British colonial rule in Singapore.

However, with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Chinese press and its cartoons refocused their attention on the war efforts back in China, with anti-Japanese cartoons appearing on the front page of the Nanyang Siang Pau. When Japan invaded Singapore in 1942, many Chinese writers and artists, including cartoonists, were executed during Operation Sook Ching, a military campaign aimed at ridding Singapore’s Chinese community of anti-Japanese elements. In response to this, and in memory of his fallen comrades, artist Liu Kang published Chop Suey, a collection of cartoons depicting Japanese atrocities in Singapore, in 1946.

Cartoons of the 1950s and 1960s

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore was a clear indication that the people could not depend on the British for protection and that they should strive towards independence. While the cartoons of the 1950s reflected the anti-colonial fervour of the times, it was not just pro-independence cartoons that were popular. Cartoons had a part to play in shaping the culture and values of a fledgling nation that was transitioning from colonial rule to self-government. Cartoons in the 1950s were also moralistic in tone, attacking the economic problems of the day and highlighting social and moral decay.

Western culture was perceived as being synonymous with decadence, and thus detrimental to the Malayan culture that local politicians, artists and writers were trying to engender. This rallying call eventually crystallised into policy in 1959 when the People’s Action Party came to power and declared war against this cultural and moral erosion.

By the early 1960s, cartoons had morphed into a consensus-building tool. Cartoons began to pointedly illustrate larger political interests, moving away from the fiery anti-colonial images of the 1950s to support the merger with Malaya. What the government wanted was a “peaceful revolution”, as cited in a Ministry of Culture publication in 1960. In line with this, cartoons in Sin Chew Jit Poh promoted social cohesion, such as the learning of Malay to create a new Malayan culture and the passing of the Women’s Charter that outlawed polygamy.

After Singapore and Malaysia separated in 1965, cartoons took on a stronger social character: promoting the nation-building process, reflecting social policy and economic planning, publicising birth control measures and emphasising the importance of a clean and green country. During this time, the Chinese press tapped on the talent of artists like See Cheen Tee, Lim Mu Hue and, later, Koeh Sia Yong.

Cartoons of the 1970s and 1980s

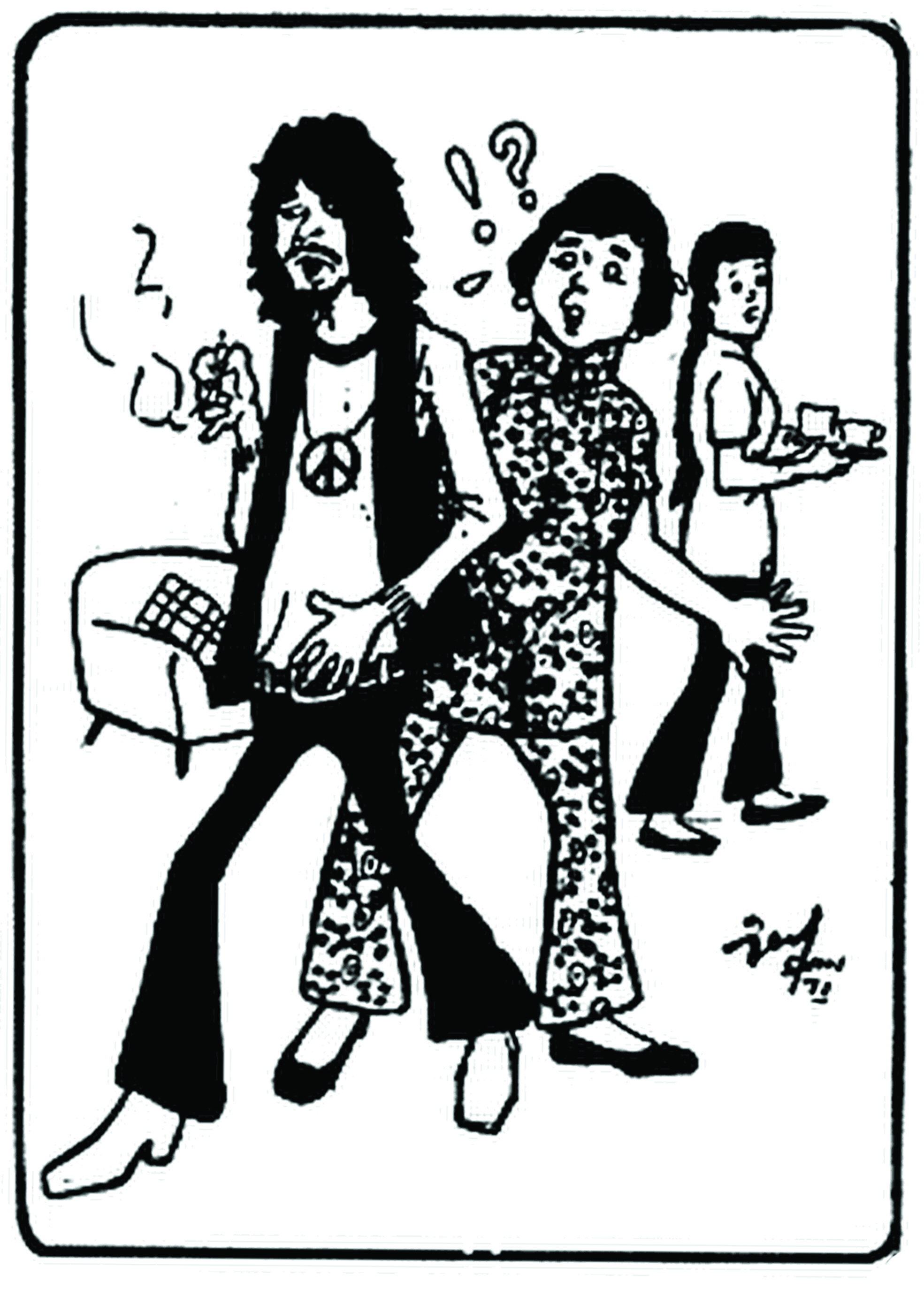

Cartoons of the 1970s marked a return to the anti-yellow culture movement. This time, they targeted the hippie culture with its drugs and sexual permissiveness, and its associations with liberal Western values. Those who went abroad to study were deemed as a social threat when they returned to Singapore. Even Bruce Lee movies were seen as promoting violence, vigilantism and unhealthy behaviour and attitudes. Sin Chew Jit Poh’s Ong Sher Shin was at the forefront of this pro-government cartoon campaign.

However, not all cartoonists promoted the state’s agenda: four Nanyang Siang Pau senior executives were arrested under the Internal Security Act in 1971 for allegedly playing up Chinese chauvinism and glorifying Chinese communism in the newspaper. In 1974, to prevent such incidents from recurring, the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act was enacted to regulate the management and operation of all newspapers in Singapore.

By the 1980s, Singapore was more confident of its position on the world stage and its own future. A new generation of cartoonists appeared on the scene, such as Lee Kok Hean (Li Tai Li) and Heng Kim Song. The former was one of the original members of Man Hua Bao, a group of young cartoonists who contributed to the Sin Chew youth supplement, Sin Chew Youth. In the early 1980s, they were an active group, creating cartoons about local life. When they disbanded in 1986, they were replaced by Man Hua Kuai Can, another student group that drew cartoons for the Sunday edition of Lianhe Zaobao.

Readers today would be more familiar with the hot-button issues that beleaguered Singapore from the 1980s onwards: falling birthrates, Chinese language issues, various financial crises, immigration controversies, the threat of SARS and the avian flu, as well as daily bugbears such as the rising cost of living. As they did in the past, the cartoons mirrored the local headlines of the day.

So what has changed in the art of cartooning, particularly in Singapore newspapers, after 90 years? In its early years, most people were illiterate and cartoons served as a powerful vehicle to convey visual ideas, employing images and simple text to carry their messages. Today, cartoons have become more sophisticated, using verbal innuendo and double entendres because the increasingly educated populace can understand these textual sleights of hand. There are also more textual and visual references to mass media as well as pop culture on platforms such as television, radio, the internet and, increasingly, social media. But it is precisely because of this competition that cartoons as a genre have become less effective as a means of communication. This is perhaps one of the key reasons why the artists who take part in 24 Hour Comics Day feel less inclined to tackle social issues of the day, preferring instead to deal with personal introspection.

Both exhibitions present a past and present view of the state of comics creation in Singapore and will hopefully inspire more people to create their own works.