On the Dining Table: Changing Palates Through the Decades

What we eat is often shaped not only by culture and tradition, but also society and government policies. Through one family’s changing palate, find out how all these factors have influenced what appears on the dining table.

When I was growing up, my grandfather’s elderly cousin would visit us during important festive occasions. The womenfolk in the family would gather to make steamed rice dumplings, or 桃粿 (tao guo; literally “peach dumplings”) to use as prayer offerings. I still remember the booming voice of my grandfather’s cousin as her large palms deftly shaped the pink-hued rice dumplings, pressing them into a wooden mould. Nowadays, no one seems to have the time to gather around the kitchen and cook while chatting in the Teochew dialect. These days, my uncles simply buy the tao guo, but it just tastes different and part of the fun is gone.

During the annual Dragon Boat Festival, my grandmother would spend days painstakingly preparing the ingredients required for making the pyramid-shaped rice dumplings called 肉粽 (rou zong). It was a tedious process: cooking red beans and grinding them into a paste; boiling dried chestnuts and removing the skin; chopping and stir-frying dried prawns, dried mushrooms and fatty pork with coriander powder and other spices; washing bamboo leaves, strings and glutinous rice; and cleaning caul fat membrane and stuffing it with a generous dollop of the red-bean paste. The ingredients were then assembled and neatly wrapped in bamboo leaves before being steamed to perfection in bamboo baskets. Nowadays, many families prefer to purchase ready-made dumplings from shops.

In recent years, there has been no lack of news lamenting the closure of many local food establishments. Most recently, in May 2013 – after 58 years of operation – the shutters came down at the iconic Mong Hing Teochew Restaurant on Beach Road. Exhausting and time-consuming food preparation, ageing cooks, the lack of successors, and rising cost of manpower and ingredients are frequently cited as reasons for these closures.

This essay examines the ethnological aspect of food and its impact on the food my grandparents, parents and my family have consumed over the decades. It offers perspectives on how our family’s eating habits have evolved over the course of three generations.

My Grandparents’ Generation: 1930s–1950s

My maternal grandmother arrived in Singapore from Guangdong province in China during the late 1930s. As a young bride, she lived with her husband and mother-in-law who were farmers. Life settled into a routine of waking up before dawn to feed the pigs and chickens, tending to the vegetable plots and cooking three meals a day. My great-grandmother would harvest the vegetables and sell them at a nearby makeshift market.

Breakfast was usually a bowl of steaming watery porridge served with some fried eggs and preserved olives; lunch comprised stir-fried vegetables and pork; while dinner was more stir-fried vegetables, along with fried or steamed fish. This was the typical fare of my grandmother’s generation. My paternal grandparents were fortunate enough to live along the banks bordering the Straits of Johor (on the Singapore side), where they enjoyed easy access to fresh seafood. As a result, freshly steamed fish and seafood, seasoned simply with salt, featured frequently at mealtimes. One of our relatives made her fish sauce as a seasoning, and it was also common for families to ferment their own rice wine for cooking. In those days, sumptuous dishes that required elaborate preparation or expensive and seasonal ingredients were only eaten during festivals and celebrations.

In Singapore, my maternal grandmother was exposed to new forms of cuisine as well as cultures. When she saw her first bowl of chendol, she thought it was disgusting how people could wolf down green worms swimming in a pool of dirty brown water. She later realised that those “worms” were actually strips of jelly made from rice flour mixed with the juice of the fragrant pandan (screwpine) leaf and green food colouring, and the liquid they were floating in was a delicious concoction of coconut milk and gula melaka (palm sugar).

There was a fourfold increase in Singapore’s population from 226,842 in 1901 to 938,144 in 1947. The growth rate gathered slight momentum after a lull period in the late 19th century, with a 3-percent increase between 1901 and 1911 and a 3.3-percent increase between 1911 and 1921. During the Great Depression, however, there was a drop of 2.9 percent due to restrictions imposed on immigrants from China and India. Then, between 1931 and 1947, the growth rate rebounded to 3.2 percent.1 My grandparents were part of this final wave of immigrants.

During the postwar period, the Chinese population dominated the influx of new immigrants. Several dialect groups lived in enclaves, particularly within the city-centre area. The Teochew community established themselves mainly on the south bank of the Singapore River. Many were employed as coolies (labourers), hauling goods between the riverside warehouses and tongkangs (local wooden boats) crowding the river. Some Teochews specialised in certain sectors of the inter-island boat trade, particularly between Singapore, West Borneo and southern Thailand where substantial Teochew trading communities were found.2 There were also others, like my grandparents and relatives, who were farmers and fishermen living in Teochew-dominated areas of Singapore like Sembawang, Upper Thomson and Punggol.

The Teochew Migrants

The Teochew migrants who arrived in Singapore from the 19th century onwards came from the Chaoshan (潮汕) region in the eastern Guangdong province of China, near the border of Fujian. This dialect group includes people from the Chaozhou (潮州), Shantou (汕头) and Jieyang (揭阳) cities. As the majority of Teochews lived by the sea or near waterways, Teochew cuisine often comprise the freshest fish and seafood. The dishes use minimal seasoning so as to enhance the natural taste of the food.

Teochew cuisine is made up of four broad categories: braised food, such as braised duck and braised pork belly; seafood dishes including freshly steamed white pomfret, steamed fishcakes and steamed mullet; pickled food like chye poh (salted radish) and dang cai (brown pickled cabbage); and lastly, dishes cooked with seasoning and sauces such as fish sauce, salted plums, kumquat oil and Teochew gong cai (a form of pickled mustard greens).

From the immediate postwar years up till the late 1960s, my grandparents lived in close proximity to their extended families and ate more or less the same meals every day. During festive seasons, food and invitations to more elaborate feasts were exchanged. Occasionally they would have their meals at makeshift stalls run by street hawkers, choosing cooked food that they were accustomed to. As unemployment rates in newly independent Singapore was high and jobs were scarce, many people become hawkers. It was definitely one of the easier ways to earn a living during those difficult times.

According to the 1950 Hawker Inquiry Commission Report, Cantonese, Teochew and Hokkien hawkers made up the largest percentage of hawkers at 30, 30 and 20 percent respectively.3 However, in the postwar years, itinerant hawkers were seen as a general nuisance to the public, obstructing roads, incessantly calling out to customers, creating trouble with their gang affiliations, and posing a serious threat to health with their unhygienic food preparation and storage. Still, there was a demand as these hawkers provided customers with easy access to reasonably priced cooked food, besides being their livelihood. The problem, however, was one of legislation. The report found that only between a quarter and a third of the hawkers were licensed, while the “remainder [were] breaking the law everyday merely in the course of earning their living”.4

My Parent’s Generation: Post-independence Singapore

After Singapore’s independence in 1965, a series of broad, sweeping changes were made by the government across all sectors, many of which were felt by the masses from the 1970s to the 1990s. The Housing and Development Board (HDB) was set up in 1960, and in the decades that followed, more and more families were resettled from kampongs (villages) to public housing blocks. Communal cooking activities were no longer possible as kitchens shrank, families became smaller and their relatives and friends were scattered all over Singapore. As more women became educated and joined the workforce, they also became less inclined to spend time on domestic affairs.

As a young wife in the 1970s, my mother enjoyed collecting recipes from newspapers and magazines, attending cooking classes at community centres, watching cooking programmes on television and buying cookbooks. My mother was able to try her hand at cooking dishes from cuisines other than Teochew. And thanks to new kitchen equipment such as the refrigerator, gas stove, cake mixer and blender, she could reduce the time spent in the kitchen preparing ingredients and cooking. The introduction of supermarkets also widened the selection of ingredients available, while imported items started making their way to the supermarket shelves.

Over time, all this had a huge impact on what we ate. Our hot porridge breakfast gave way to the more convenient combination of bread, butter and jam, and our mealtimes saw greater variety on the table as Mum grew adventurous and experimented with new dishes. However, during important festivals and celebrations, we would still indulge in grandmother’s and mother’s traditional Teochew cooking. The success of the Speak Mandarin Campaign introduced in 1979 eroded our ability to converse in fluent Teochew. Today, my siblings and I are not as well versed in the Teochew dialect; as a result, cooking instructions issued to us in this Chinese dialect by our grandmother are sometimes lost in translation. Occasionally, grandmother would share Teochew food aphorisms such as 三四桃李奈 and 七八 油甘柿 (meaning “peaches, apricots and plums ripen during March and April” and “Indian gooseberries and persimmons are ready to be eaten in July and August”) and dispense practical advice such as 稚鸡, 硕鹅, 老鸭母 (meaning “young chicken, mature goose and old duck are the best stages of their growth for cooking”).

After 1971, when the Singapore economy became more stable, the government was able to focus on reining in unlicensed cooked-food hawkers. Many of them were relocated from the streets and alleys to centralised hawker centres that were installed with piped water, sewers and garbage disposal facilities. By the early 1980s, all of the hawkers in Singapore had been resettled in hawker centres.5 With increasing affluence, more families could afford to eat out. Hawker centres, with their affordable prices and variety of food, became sought-after places for people to have their meals, and have since become an indispensable part of Singapore’s culinary landscape.

In 1986, 30 percent of people aged between 15 and 64 ate breakfast outside the home, while 54 percent and 12 percent ate out for lunch and dinner respectively.6 As early as 1979, it was reported that the changing lifestyles of Singaporeans had led to an increase in diseases that were linked to unhealthy eating habits and harmful lifestyles.7 A household expenditure survey conducted between 1987 and 1988 reported that “hawker foods accounted for almost 80 percent of an average household’s cooked food budget”.8 In 1992, Dr Aline Wong, then Minister of State (Health), encouraged Singaporeans to eat more homecooked meals as it was perceived to be healthier.9

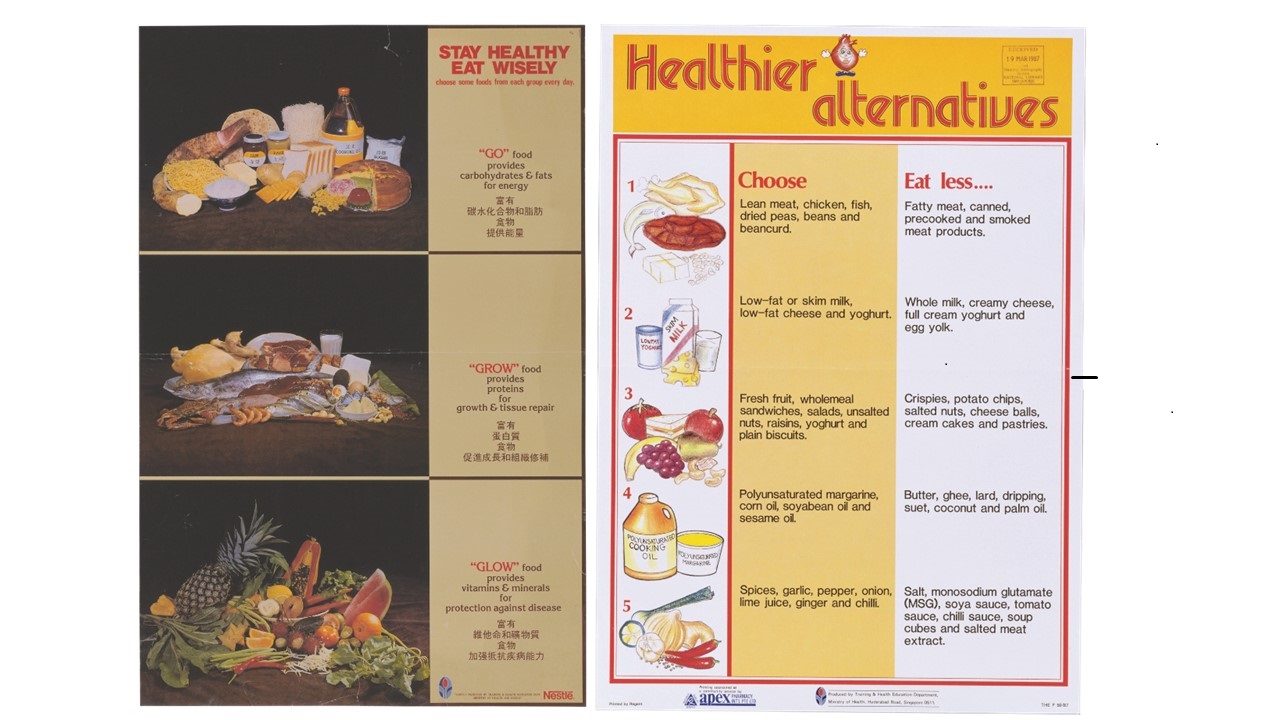

The Ministry of Health launched studies of the food consumed by Singaporeans. One of the earliest projects was conducted by the Institute of Science and Forensic Medicine under the Ministry of Health in 1992. The following year, 200 commonly available foods at hawker centres were subjected to chemical analysis by laboratories commissioned by the Food and Nutrition Department. A series of booklets on food and nutrition was published and distributed to the public, covering subjects such as healthy eating at childcare centres, serving healthy food to students, healthier menu choices for workplace canteen operators, coffeeshops and restaurants, and a guide to making sensible food choices at hawker centres.

Over the years, changes in lifestyle, national campaigns, and new ways of storing, processing and cooking food have contributed to changes in our diets. The author of Soya & Spice, Jo Marion Seow, lamented that some food “[has] gone the way of the dinosaurs”, citing the example of the cheap preserved or pickled side dish known as zahb khiam in Teochew, which was commonly eaten with porridge.10

Certain common hawker dishes have also been gradually disappearing from the culinary horizon. Local food blogger Dr Leslie Tay noted a steady decline in the standards of char kway teow (fried rice noodles) as the dish has come to be regarded as “unhealthy and the fear of contracting Hepatitis A from eating partially cooked cockles has put another nail in the coffin”.11 He also remarked that Teochew eateries no longer use the meaty Asian carp in traditional fish head steamboat. These days, the “muddy-tasting” freshwater fish has been replaced by more popular varieties such as pomfret and grouper.12 Mass-produced pre-cooked ingredients manufactured by factories and supplied to hawkers have also contributed to this loss of food heritage: hawkers’ culinary skills among hawkers have been eroded by these shortcuts, and many complain that the old-style dishes just do not taste the same anymore.

My Generation

The loss in food heritage is also felt in the home. My family does not consciously partake of traditional Teochew cuisine at home anymore. Everyday dishes are not uniquely Teochew, except for special occasions such as festivals and celebrations when our family buys Teochew confectionery or steamed kueh (cakes).

In 2013, four students from the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information at the Nanyang Technological University worked on a project that aimed to raise awareness of the origins of Singapore’s food heritage. They interviewed hawkers of signature local dishes. The findings – sponsored by the National Heritage Board and supported by the Singapore Memory Project.

Deborah Lupton is of the view that “food consumption habits are not simply tied to biological needs but serve to mark boundaries between social classes, geographical regions, nations, cultures, genders, life cycle stages, religions and occupations, to distinguish rituals, traditions, festivals, seasons and times of day”.13 Where food can be culturally reproduced from generation to generation, it is a denominator that distinguishes one group from another. The act of preparing food is “part of [an] individual’s incorporation into a culture, of making it ‘their own’, which then culminates in the act of eating … [and] sharing the act of eating brings people into the same community”.14

In this respect, food helps strengthen group identity. Therefore, what we eat, how we eat, and how we feel about it reflects our perception of ourselves in relation to others. Katarzyna Cwiertka also observed that “not only do global brands spread worldwide [diminish] the diversity of local cuisines, but new hybrid cuisines are created and new identities embraced through the acceptance and rejection of new commodities and new forms of consumption”.15

With the plethora of cuisines competing for attention today, it is impossible to retain the exact ingredients and time-honoured cooking methods that our forefathers used. Like all cuisines, Chinese dishes, too, have evolved, incorporating ingredients that were previously alien to its form, like peppers, peanuts, tomatoes and corn.16 The art of eating is a constantly evolving repertoire of recipes old, new and invented. Each dish will enjoy a “shelf life” depending on its popularity and acceptance. Over time, a new concoction may be accepted as a signature dish by members of a particular ethnic or dialect group, who come to embrace the dish as their own.

Lenore Manderson sums it up by writing that the changes in the mode of production may affect food resources while offering new items, thus leading to dietary changes. The “marking, enactment and elaboration of key cultural and life-cycle events through the use of food further determine dietary variation seasonally and throughout the life span … and the allocation of food within the domestic sphere and in the larger community; the style and elaborateness or simplicity of the preparation and presentation of food, and the particular responsibilities of individuals in these activities … all provide a key to social life and to the role and status of members of a given society”.17

The Challenge of Preserving our Food Heritage

My grandparents came from a homogeneous community where everyone spoke the same language and shared the same cultural practices and values. When they migrated to Singapore, they discovered new languages, cultures and food, while still living among people from the same dialect group. In contrast, my parents’ generation interacted more with people from other ethnic and dialect groups through school or work, gaining an understanding of other cultures and their practices.

Today, changes in lifestyle, a greater awareness of nutrition and health, and the accessibility to delicious food from all over the world threaten the culinary heritage of our forebears. People rarely have the time to cook at home and sit down to a leisurely meal of homemade dishes. The days of communal cooking in a large kitchen with lots of people chatting animatedly, while hands are busy chopping, cutting and frying, are long gone. It is quite different cooking alone in a small kitchen after a hard day at the office, or relying on a domestic helper to prepare the family meals. Without constant pointers from elderly folks on the significance of certain dishes, or gentle reminders on the right cooking methods or techniques, it will be impossible to replicate the dishes of an earlier generation. The onslaught of Western food and the assimilation of other cultures coupled with the unavailability of certain ingredients from yesteryear present further challenges to preserving Singapore’s food heritage.

Given an option, will the younger members in my family choose a simple dish of Teochew caramelised yam cubes over the assortment of potato crisps in exotic flavours spilling over from supermarket shelves? There is growing nostalgia over the gradual loss of traditional food and authentic hawker fare, and both individuals and the government are trying to take steps to preserve Singapore’s culinary heritage. It will be a shame if one day, my family’s memories of traditional Teochew food become something that can only be found in books in the library or in a museum.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Reference Librarian at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Board. Her responsibilities include managing and developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Reference Librarian at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Board. Her responsibilities include managing and developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.REFERENCES

Cwiertka, K., & Walraven, B. (Eds.). (2001). Asian food: The global and the local. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press. (Call no.: R 394.1095 ASI)

Drive to fight harmful life styles. (1979, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Home-cooked vs hawker food. (1992, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kong, L. (2007). Singapore hawker centres: People, places, food. Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 381.18095957 KON)

Lee, K.Y. (2000). From third world to first: The Singapore story, 1965–2000: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore: Times Editions: Singapore Press Holdings. (Call no.: RSING 959.57092 LEE)

Lupton, D. (1996). Food, the body, and the self. Calif.: Sage Publicatons. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Manderson, L. (1986). Shared wealth and symbol: Food, culture, and society in Oceania and Southeast Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.5099 SHA)

Neville, W. (1969). The distribution of population in the postwar period. In J.B. Ooi & H.D. Chiang (Eds.), Modern Singapore. Singapore: University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 OOI)

Newman, J.M. (2004). Food culture in China. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. (Call no.: R 394.120951 NEW)

Saw, S.H. (2007). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW)

Seow, J.M. (2009). Soya & spice: Food and memories of a Straits Teochew family. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 SEO)

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission. (1950). Report of the hawkers inquiry commission. Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.798095957 SIN)

Singapore. Ministry of Health, Food and Nutrition Dept. (1993). The composition of 200 foods commonly eaten in Singapore (p. 1). Singapore: Food and Nutrition Dept., Ministry of Health. (Call no.: RSING 641.10212 COM)

Tay, L. (2012). Only the best!: The ieat, ishoot, ipost guide to Singapore’s shiokiest hawker food. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 TAY)

张新民 [Zhang, X.]. (10 May 2013). 潮汕饮食词条 [Chaoshan food entry]. Retrieved from http://wh.csfqw.com/w/csys/44122282.htm

NOTES

-

Saw, S.H. (2007). The population of Singapore. (p. 11). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW) ↩

-

Neville, W. (1969). The distribution of population in the postwar period (p. 59). postwar period (p. 59). In J.B. Ooi & H.D. Chiang (Eds.), Modern Singapore. Singapore: University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 OOI) ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission. (1950). Report of the hawkers inquiry commission (p. 69). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.798095957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore. Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950, p. 7. ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (2000). From third world to first: The Singapore story, 1965–2000_: _Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (p. 200). Singapore: Times Editions: Singapore Press Holdings. (Call no.: RSING 959.57092 LEE) ↩

-

Kong, L. (2007). Singapore hawker centres: People, places, food (p. 104). Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 381.18095957 KON) ↩

-

Drive to fight harmful life styles. (1979, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of Health, Food and Nutrition Dept. (1993). The composition of 200 foods commonly eaten in Singapore (p. 1). Singapore: Food and Nutrition Dept., Ministry of Health. (Call no.: RSING 641.10212 COM) ↩

-

Home-cooked vs hawker food. (1992, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Seow, J.M. (2009). Soya & spice: Food and memories of a Straits Teochew family (p. 9). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 SEO) ↩

-

Tay, L. (2012). Only the best!: The ieat, ishoot, ipost guide to Singapore’s shiokiest hawker food (p. 49). Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 TAY) ↩

-

Lupton, D. (1996). Food, the body, and the self (p. 1). Calif.: Sage Publicatons. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Lupton, 1996, p. 25. ↩

-

Cwiertka, K., & Walraven, B. (Eds.). (2001). Asian food: The global and the local (p. 2). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press. (Call no.: R 394.1095 ASI) ↩

-

Newman, J.M. (2004). Food culture in China (p. 94). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. (Call no.: R 394.120951 NEW) ↩

-

Manderson, L. (1986). Shared wealth and symbol: Food, culture, and society in Oceania and Southeast Asia (p. 1). New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.5099 SHA) ↩