Communal Feeding in Postwar Singapore

The colonial government’s communal feeding programme was a novel response to chronic food shortages and malnutrition in the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation, and laid the foundation for social welfare schemes in Singapore.

Between June 1946 and August 1948, Singapore’s colonial government operated a novel communal feeding programme. Supervised by the Singapore Department of Social Welfare, the programme aimed to provide one nutritious meal a day for Singaporeans at affordable prices. Mainly targeted at workers, the meals were provided by the so-called People’s Restaurants located in different parts of the city.

Over two years, the feeding programme expanded to include a catering service, financial support for the creation of private canteens and a children’s feeding scheme. Though short-lived, the impact of the programme was wide-ranging. It eased considerable pressure on the colonial government at a time when food was scarce, helped established a new social welfare department, and laid the foundations for Singapore’s postwar social welfare landscape.

Origins of the Food Programme

The return of the British after World War II did not bring immediate relief to Singapore and its people. Their delayed return after the sudden surrender of the Japanese had resulted in a gaping void. The Malayan Anti-Japanese People’s Army (MPAJA) poured out of the jungles and attempted to establish its authority in Singapore and Malaya – often violently. Political challenges aside, a critical shortage of rice in Southeast Asia also threatened to undermine British authority with worsening malnutrition and a rampant black market.

The communal feeding programme can be attributed to the recommendations of the Wages and Cost of Living Committee. In May 1946, an inquiry to review the wages of the clerical and working class was commissioned in response to the rising cost of living, particularly the cost of food. After witnessing the desperate conditions of workers, the committee recommended several interim measures, such as temporary cash allowances, capping of food prices, the setting up of canteens by government departments and employers with the means to do so, and opening “in all large urban areas” public restaurants “on the lines of British Restaurants in the United Kingdom”.1 The committee also recommended that the canteens and restaurants “should not be operated under contract but should be run directly by a division of the Welfare Department”.2

The British concept of subsidised state feeding originated in the early 20th century. An emerging social consciousness encouraged the expansion of the state feeding programme. It began with prisoners and the poor and later included schoolchildren and factory workers.3 Eventually, this led to the creation of community restaurants known as National Kitchens during the Great War and then British Restaurants during World War II.4 State provision of food not only helped ration limited foodstuffs, but also raised overall morale during times of war and strife.

The People’s Restaurants

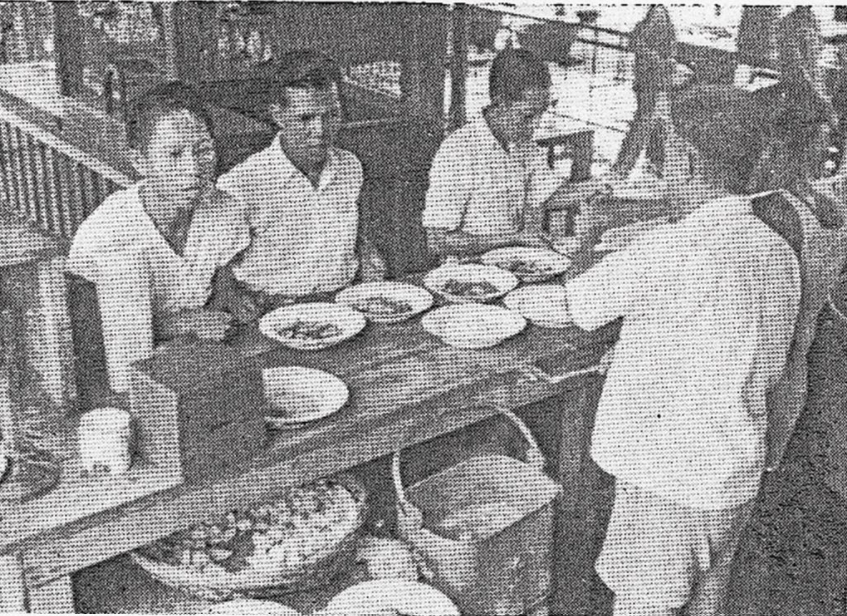

On 29 June 1946, the first People’s Restaurant opened in a converted godown at Telok Ayer.5 Tan Beng Neo, a Salvation Army volunteer, described the restaurant as an “attap [palm-thatched] shack with barbed wire fencing”, and recalled that they managed to sell two to three thousand meals in two hours.6 The first meal consisted of “rice, pork and vegetables, or rice and fish curry for Muslims, and a mug of iced water”.7 Nutrition experts from the King Edward VII College of Medicine ensured that each meal was “not only tasty, but good”.8 For 35 cents, customers received roughly 700 calories of rice, meat and vegetables, or a third of their daily nutritional needs, with coffee or tea.

The Social Welfare Department’s first official report, Beginnings, describes the process of buying lunch:

“The customer enters by one of perhaps several lanes leading to a ticket box. He buys his ticket and passes on to a long serving counter where the complete meal is handed to him in a mess tin [or an enamel plate] by a server in exchange for his ticket.

On his way to his table he passes other counters where he can pick up his spoon and his mug, and dip them in a sterilizer; where he can collect files past yet another counter where occasionally he will find on sale things like fruit, tinned provisions and cigarettes, which otherwise he could only get at inflated prices from profiteering street hawkers, agents for the most part of the black market.”9

By the end of 1946, about 10 People’s Restaurants were in operation at refurbished godowns or as part of existing buildings, including one in the “boxing arena of an Amusement Park”.10 These restaurants were located in “Telok Ayer, Seng Poh Road, Queen Street, Handy Road, Happy World, Katong Kitchen/New World, Maxwell Road, and Harbour Board”.11 As the People’s Restaurants were targeted at workers, it only served lunch five days a week.

Feeding Schemes

Overseen by a committee that included Lim Yew Hock and Goh Keng Swee (Singapore’s second chief minister and second deputy prime minister respectively), the communal feeding programme expanded to include various schemes such as the People’s Kitchens, Sponsored and Approved Restaurants, Family Restaurants and children feeding centres.

The People’s Restaurants were limited to the city and could not serve factories and workshops in isolated locations. The Social Welfare Department worked with the Labour Office to sponsor “the formation of factory canteens, with the latter arranging permits for the supply of controlled foodstuffs and the former provid[ing] the expertise and resources to get the canteens going.”12 About 60 Sponsored Restaurants were established between July and December 1946.

The Social Welfare Department also attempted to work with existing restaurants and invited applications for the Approved Restaurants scheme, where successful applicants could buy controlled foodstuffs on the condition that meals were sold at prices determined by the department. Although close to 200 applications were received, only a very small number were deemed suitable after assessment. As such, the scheme was scrapped in favour of other feeding programmes to cater to more urgent needs.

To reach out to more people quickly and efficiently, the Social Welfare Department established centralised People’s Kitchens, which could supply “any number of ready-cooked meals in bulk to any unit anywhere in the Colony”.13 At the peak of the feeding programme in October 1946, nearly 40,000 lunches were cooked and served daily. Within a mere six months, over one million meals had been served to the hungry public.14

The Social Welfare Department paid more attention to those who could not even afford the 35-cent meal. It was recognised early on that the 35-cent meal was not often “within the reach of the poor, the old, the unemployable and the many-progenied”.15 In December 1946, the first Family Restaurant opened on Maxwell Road, selling lunch at only 8 cents per meal. Benefiting from the bulk purchase of army foodstuffs, the department ensured that the 8-cent meal was similar in proportion to the 35-cent version and even lowered the price of the latter to 30 cents for most of 1947.16 Demand for the 8-cent meal was sufficiently high – all 2,500 meals were sold out on the first day – and three existing People’s Restaurants were converted into Family Restaurants by the end of 1946.17

Publicising the Feeding Schemes

These feeding schemes catered mostly to the working population. According to Secretary for Social Welfare Percy McNeice, the main objective was to “counteract the black market.”18 It was not enough just providing cheap meals. The word had to be put out to the general public that nutritious food was readily available at inexpensive prices.

The day after the Wage and Cost of Living Committee announced its recommendations on 27 June 1946, the colonial government ran an announcement in The Straits Times about the 35-cent lunch being a “reality”.19 Both the Governor of Singapore and the Colonial Secretary sat down to lunch at the People’s Restaurant at Telok Ayer on the opening day, which was duly reported in The Straits Times.20 In the same article, McNeice fired the opening salvo of a rather public battle with the black market. Under the sub-heading “Killing Black Market”, McNeice declared: “Our main purpose is to reduce prices and to put a stop to the black market.”21

There was an immediate reaction as rumours began circulating that the cheap meals were only possible because of government subsidies.22 McNeice responded by giving a detailed interview to The Straits Times, explaining how the 35-cent meal was put together and cited the prices of the various foodstuffs purchased by the department.23 McNeice declared that all food purchases had been made in the open market (at government controlled-prices), and even after taking into consideration the salaries of the cooks and staff, the feeding programme was able to turn a small profit. He observed that people were still paying too much for food and offered his services to any restaurateur willing to sell meals at the department’s prices.

The novelty of the communal feeding programme quickly gained traction, and it pressured existing restaurants to at least provide better value for meals they served. The Singapore Free Press conducted a before-and-after survey of a particular restaurant that had consistently flouted the maximum controlled price of three dollars per meal.24 Once the People’s Restaurants started, the restaurant served visibly bigger portions, even if the price was not reduced.25 The Sponsored Restaurants scheme also helped spread the message that cheap meals were possible. For instance, on 19 July 1946, the owners of Singapore’s leading Chinese newspaper, the Sin Chew Jit Poh, opened a staff canteen where meals could be had at only 10 cents.26

In its first year or so, the People’s Restaurants and the other feeding schemes were in the news almost every other day. Between September 1946 and May 1947, announcements titled “Today’s Menu”, which informed the public of the meal (or meals) of the day, were regularly published in The Straits Times.27 Editorials were mostly positive about the impact of the feeding schemes, with one claiming that “Singapore Did Not Starve” due to the department’s efforts.28 When the Malayan Union (1946–48) started its own People’s Restaurants in its territories across the border, Singapore’s Social Welfare Department was actively consulted on its feeding programme,29 suggesting that the People’s Restaurants and its ancillaries may have helped Singapore and Southeast Asia avoid famine during this period.30

Rice, boiled chicken with white sauce, or rabbit stew, green peas, chye huay

Fried mee, beef or prawns, bean sprouts; bean cake, choy sim

Rice, vegetable omelette with tomato or paprika sauce or New England [sic]

Rice, fish fritters with tomato sauce, spinach, beetroot

Noodles and goulash or Hokkien mee, beef or prawns, choy sim, towgay

Noodles in Amoy or Java style

Rice; bean cake with garnishment; peanut butter, sambal

Rice and New England [sic] or beef stew and vegetable, omelette

Rice; Vienna sausages; bean cake and mixed vegetable stew, tomato sauce

Fried noodles, bean cake, towgay, kangkong

Rice; fish curry; or masak asam; salad (cucumber, kangkong); tomato sauce

Rice; chicken or rabbit stew or chicken kruma; yam beans and chye huay

Hokkien mee; beef soup; prawns; brown fried onions; green chilli; bean sprouts; watercress

Rice; fried liver or liver curry; pak choy; green peas, tomatoes; peanut butter; gravy

Fried noodles; beef stew and fried prawns; choy sim and towgay

Rice, roast chicken or turkey or chicken curry, long beans, spinach

Rice, beef and onions with garnishment, bayam and green pea sprouts

Fried noodles, fried pork and prawns, towgay, fried onions, koo chye, chew chow and choy sim

Rice, steamed or fried fish, onions, tomatoes, spinach

Rice, braised pork (Chinese-style) or fish, special mixed chup chye, cucumbers

Rice porridge (bubor), meat balls and salted vegetables with garnishment

Rice; beef stew and green peas or beef curry; marrow and chye sim

The response from the general public was more mixed. Some were pleased with the initiative and asked for similar restaurants to be opened in their vicinity; one asked for a 40-cent meal with more rice and food;31 others voiced suspicions about government profiteering.32 The public also wrote several letters to the Social Welfare Department, pointing out gaps in service.

By April 1947, the Social Welfare Department felt confident enough to announce the success of its feeding schemes.33 In June 1947, the department introduced 50-cent lunches, in addition to the 30- or 35-cent versions, to meet increasing demand for meals with larger quantities and better ingredients as the economic situation eased.34 The demand was a clear signal that the hungry customer with spending power wanted more than the department’s inexpensive but limited meal options.

The easing economic situation also resulted in the decline of demand for the Department’s meals throughout 1947. Between June and December 1946, 1,321,115 meals were cooked and served by the People’s Restaurants and People’s Kitchens, while the number of meals for the whole of 1947 only reached 1,575,640, with the daily average falling from 6,000 meals in January 1947 to about 4,000 in December 1947.35 The declining demand meant that it was no longer cost-effective to continue the feeding schemes. In August 1948, the People’s Restaurants were officially closed and the other feeding schemes discontinued or scaled down.36 Over two years, close to 3.5 million meals via the People’s Restaurants and the People’s Kitchens were served.37

The Children’s Feeding Scheme

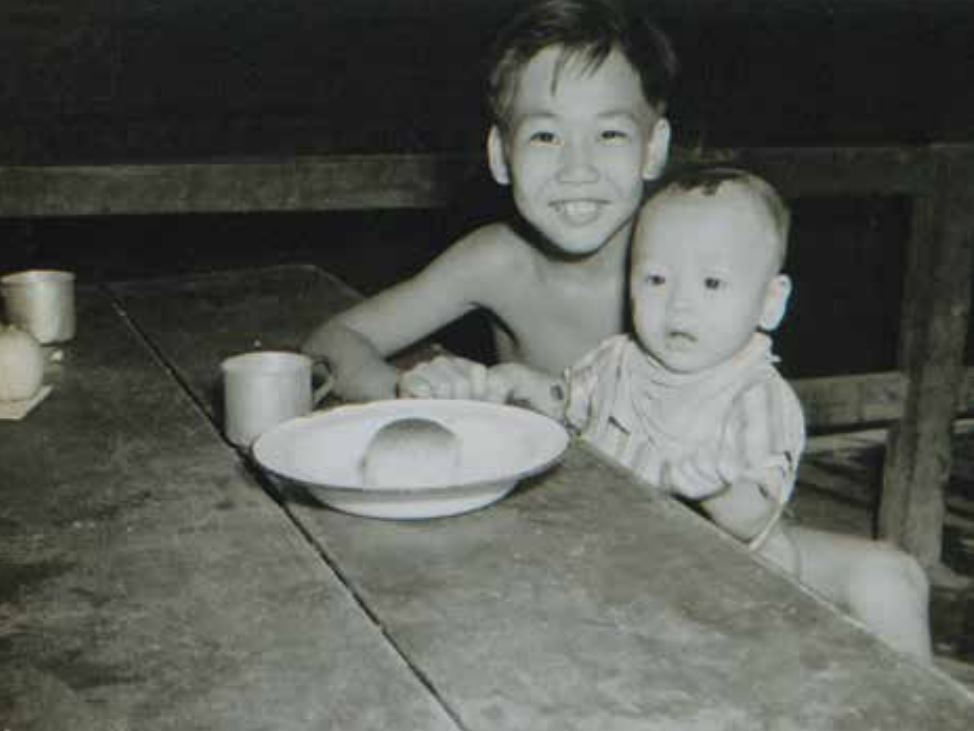

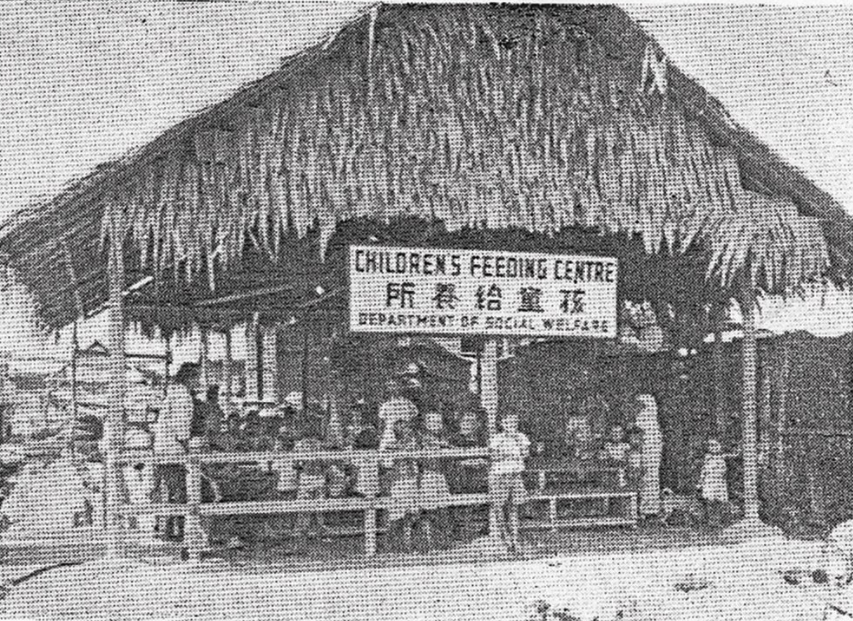

The relative success of the communal feeding programme provided the colonial government with ready-made mechanisms to implement policies that were otherwise difficult to put in place. A case in point was the Children’s Feeding Scheme, a programme that actually predated the various feeding schemes and the Social Welfare Department – both of which were established in June 1946.

The well-being of children was an urgent priority for the British. As a result, the Child Feeding Committee was formed, represented by both the government and social groups, to specifically address the issue of child nutrition.38

A nutrition survey conducted in late 1945 found that malnutrition among children was widespread. Emboldened by the survey results, the committee proposed to provide all children in Singapore with one nutritious meal a day. But financial and logistical limitations meant that the scheme remained small. The Education Department began trial runs in three schools, while the Medical Department implemented an infant-feeding scheme at two clinics.39 Further expansion of the scheme depended on the availability of necessary equipment and when the scheme was more “thoroughly organi[s]ed”.40 From November 1945 to April 1946, over 32,000 meals were served to children at the medical clinics. A further 200,000 meals were served to schoolchildren, at an average of 2,300 meals per day.41

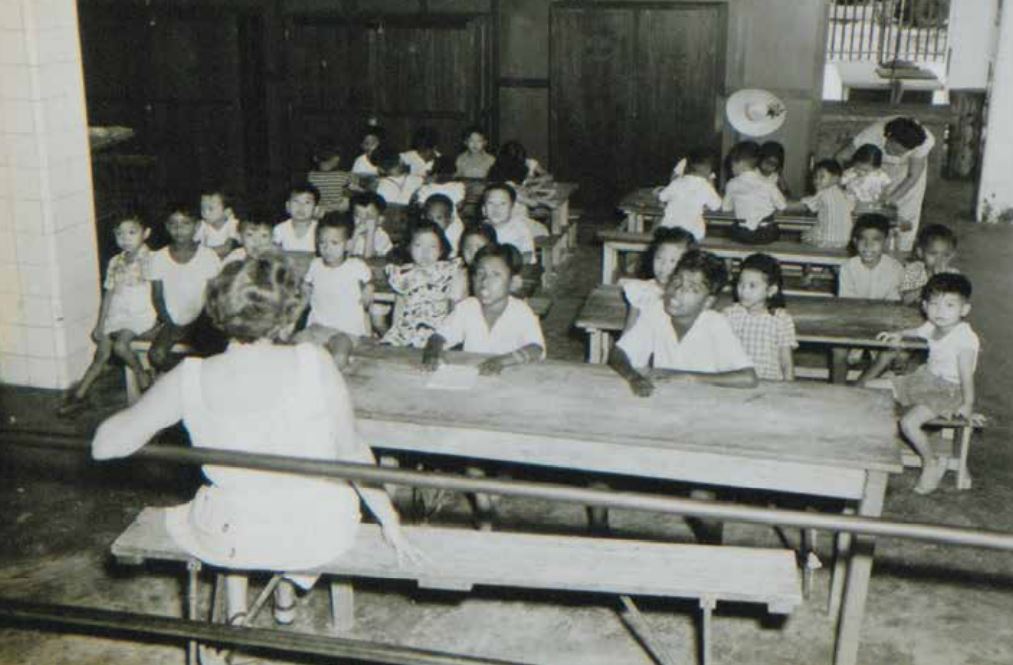

The succeeding civil government set aside $360,000 to provide free meals to children aged between two and six in 1947.42 The first Children’s Feeding Centre was opened in January 1947. Nine similar centres followed in February; by the end of the year, 23 centres were in operation, serving a total of 810,000 meals to about 40,000 children, at a daily average of some 4,000 meals.43

These seemingly rosy statistics, while showing that more children were helped via the programme, tell only half the story. As the scheme lacked financial support, child feeding efforts throughout the British Military Administration period remained small. Both military and civil governments had initially perceived the child feeding scheme as temporary. In mid-1946, meals for schoolchildren, already limited to a small number of schools, were so threatened that direct appeals were made to the British Prime Minister.44 Problems continued even after the Social Welfare Department took over.

From the start, McNeice was not keen on taking over the scheme as the government could not guarantee the necessary funds. The first child feeding centre was to open in November 1946, but it only commenced operations two months later as uncertainty over funding led McNeice to put the entire scheme on hold.45 When the funds were eventually approved, the amount provided was only enough for children aged between two and six, excluding infants and schoolchildren.46 Even then, the meals could only be given to children whose families were already receiving assistance from the Social Welfare Department. Money was tight and the postwar rehabilitation of Singapore was costly. The creation of new government departments, such as the Social Welfare Department and its services, came under some scrutiny and even criticism towards the end of 1946.47

Despite the obstacles, the Department succeeded in establishing over 20 children feeding centres by the end of 1947, aided by the central kitchens supporting the communal feeding programme. The meals were “prepared according to the specifications provided by the Professor of Bio-Chemistry of the College of Medicine”.48 Each meal usually consisted of rice, green peas, green vegetables and ikan bilis (dried anchovies) and was supplemented by milk and fresh fruit.49 The centres were slightly different from the People’s and Sponsored Restaurants. Unlike the latter, the children feeding centres were managed by volunteers, mostly women. A core group, made up of the spouses of British officials and local elites, was led by Lady Dorothy Gimson, wife of the Governor of Singapore. Additionally, volunteers came from the Chinese community, such as the Singapore Women Federation, Singapore Chinese Women Association and Singapore Women Mutual Aid Association of Victims’ Families. Other volunteers also came forward in their personal capacities, offering their residences as feeding centres.50

The centres were visited by a team of two medical doctors to observe and chart the children’s health. The health aspect needed urgent attention. Some 4,000 children were medically examined at the start of the scheme, and most of them were found to be underweight and in poor physical condition. Almost all of them suffered from more than one medical condition, such as decayed teeth, swollen gums and anaemia. The children who were accepted into the scheme were only the tip of a larger poverty problem. A Singapore Free Press correspondent also observed how several youths – who did not qualify for the scheme – would surreptitiously eat half the meals belonging to their younger siblings. A regular volunteer at the Mount Erskine centre, Lady McNeice (née Loke Yuen Peng), the wife of Percy McNeice, recalled how “the older brothers and sisters used to come along the centres and look longingly at what was being done for the younger children”.51 She described mothers with 10 or 12 children going to the volunteers seeking help because they did not want any more children.52 Confronted with the daily sight of child poverty, several female volunteers, led in particular by Constance Goh (née Wee Sai Poh), introduced family planning methods to those who sought assistance.53 This eventually led to the establishment of the Singapore Family Planning Association in 1949.54

The nature and purpose of the feeding centres also evolved. Volunteers at several centres introduced various social and educational activities to keep over-aged kids who did not qualify for the free meals occupied so as to not disrupt the centre.55 Such activities were planned and managed by a committee of lady volunteers led by Lady Gimson. The committee also raised funds to pay for manpower, equipment and programmes, beyond what the Social Welfare Department could provide. From January 1948, the centres were renamed Children Social Centres, as the centres began providing “elementary education in English and Chinese” and a host of handicraft and artwork activities.56

In 1948, the number of children below school-going age – the target group of the scheme – who benefited from the programme fell from over 750,000 in 1947 to below 500,000.57 In the same year, the Social Welfare Department began winding down its communal feeding programme, which officially ended in August 1948. At the same time, the fleet of mobile canteens was also reduced, resulting in a decrease in the number of children that could be reached. Out of the over 20 feeding centres, only four allowed children to consume their meals there, while the other centres were supplied by mobile canteens. The loss of mobile canteens made it inconvenient for mothers to bring their children to the “static” centres – some of which were quite a distance from their homes – for only a few hours.

A contributing factor for the change was financial. Feeding centres were further reduced to 16 “static” centres by the end of 1948.58 In 1949, the Social Welfare Department made a passionate defence of the Children’s Feeding Scheme in its annual report. The Legislative Council had approved funding for the scheme for only six months in 1950. The council also requested for a committee to look into the viability of the scheme.59 The committee recommended that the scheme continue, but to replace the cooked rice meal with a supposedly more nutritious meal comprising bread, milk and fruits. Costing 8 cents per meal, compared to the previous 15 cents per cooked meal, the new meal was undeniably cheaper. Unwittingly, perhaps, it also indicated that the new meal merely supplemented the family diet.60

The Impact of Communal Feeding

It is difficult to conclude decisively whether the People’s Restaurants and the other communal feeding schemes broke the grip of the black market. While useful, statistics are limited in providing an overall picture. Declining attendance at the People’s Restaurants throughout 1947 did not necessarily mean that the black market was in retreat. It could have indicated that wages on the whole were increasing, hence allowing the individual more choices. Similarly, the popularity of the People’s Restaurants during the first six months of operations did not necessarily mean that fewer people patronised the black market. It could have simply been a situation where there was insufficient food, especially rice, to go around, and the people were taking advantage of a cheap alternative in tandem with the black market.

Southeast Asia had been threatened by a critical shortage of rice since the beginning of 1946, which deteriorated into a full-blown crisis by August.61 The regional rice crisis and the global food shortage cast the publicity efforts of the Social Welfare Department and the colonial government in a different light. Such efforts had visibly petered off by mid-1947 when the food crisis abated. The initial slew of positive news and announcements seemed a deliberate attempt to placate the population with semi-good news or at least reassure them with the promise of decisive state action so as to prevent industrial and social unrest.

As far as anecdotal evidence went, the feeding programme did force prices down. On the final day of the People’s Restaurant scheme, the Social Welfare Department observed that a plate of rice and curry had gone down from $1.50 to 50 cents in two years.62 The proliferation of Sponsored Restaurants – over 60 such ventures continued after the official end of the feeding programme – could be an indication of private and public support. At worst, the Social Welfare Department’s feeding programme arguably kept the peace by acting as a pressure-relief valve by providing an accessible and affordable alternative source of meals during a period of severe food shortages.

The programme was lauded globally, with countries like India and China seeking advice from the Social Welfare Department and the Singapore government. One positive effect of the programme was its success in establishing a fledgling social welfare department and social welfare as a function of government. The presence of a government social welfare department arguably reversed the laissez-faire approach to governance that had guided the development of Singapore since 1819.

The feeding schemes marked the beginning of greater involvement by the state in Singapore, to the extent that the government assumed responsibility for some aspects of the society’s welfare. The current Ministry of Social and Family Development, successor to the Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports, acknowledges the feeding schemes as a historical milestone.63

The development of the Children’s Feeding Scheme is also insightful. It faced many obstacles and probably would have failed without the female volunteers. Indeed, the colonial government, in attempting to implement a social welfare policy, had from the beginning stressed the importance of “unofficial” or nongovernmental associations as they would theoretically be better placed to understand local needs.64

In this particular case, civil society not only played a practical role (providing otherwise unavailable resources such as labour and physical sites), but was also instrumental in influencing and shaping state policy. What had started out as a relatively uncomplicated scheme to provide adequate nutrition for children evolved into a programme that provided educational and social development activities, positioning the children social centres as the forerunners to present-day childcare centres. State policy was also affected by the response of the women volunteers to the sight of wretched poverty. The Singapore Family Planning Association founded by these women became the basis of state efforts to manage the population of postcolonial Singapore.65

THE PRINSEP STREET CHILD FEEDING CENTRE

In February 1947, the Singapore Free Press ran an article offering a glimpse of a day’s activities at the Prinsep Street Child Feeding Centre:

“At nine o’clock in the morning children began gathering outside the gates of the Centre. At 9.30 the gates are opened by a burly Sikh who lets the children run into the Centre in small groups. The rest of the children play outside or pacify their smaller brothers and sisters until their turn comes to file into the weighing room. Each child is weighed at regular intervals before going into the dining room and the records are sent to Dr. Oliveiro, head of the Nutrition Unit of the King Edward VII College of Medicine. After being weighed the children file past a window where their cards are endorsed for each meal and they are each given a metal disc entitling them to one meal. Once they have passed the window all their orderly quietness deserts them – they race down the passage shouting to their friends and pushing to get ahead of one another at the serving counter. The metal disc [is] drop[ped] into a mug and they pick up their mess tins and mugs and make straight for the table they chose to sit at. [The] centre is something of a social club for these small children. They walk between the tables wondering with whom they will sit and the older children chat and laugh as they shovel food into the babies’ mouths.” 66

References

Fraser, D. (2003). The evolution of the British welfare state: A history of social policy since the industrial revolution. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Kratoska, P.H. (1988, March). The Post-1945 food shortage in British Malaya. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 19 (1), 27–47. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Malayan Union. The wages and cost of living committee. (1946). The interim report of the wages and cost of living committee. Singapore: G.P.O.

McNeice, L.P. (1982, August 4). Pioneers of Singapore. In the collection of Oral history recording database. National Archives of Singapore.

McNeice, T.P.F. (1981, November 10). The civil service – A retrospection. In the collection of Oral history recording.

Singapore, British Military Administration Chinese Affairs. (n.d.). Social welfare. [Long-term policy directive for Social welfare]. British Military Administration Chinese Affairs (27/45). Government Records Information database.

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1947). Beginnings: The first report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare, June to December 1946. Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RRARE 361.6 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL28506).

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1948). The second report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare 1947. Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RSING 361.6 SIN).

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1949). The third report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare 1948. Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RSING 361.6 SIN).

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1946–1979). Annual report. Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. Available via PublicationSG.

Singapore. Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports. (2007). Helping hands, touching lives. Singapore: Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports. (Call no.: RSING 361.95957 HEL).

Tan, B.N. (1983, November 26). Women through the years: Economic and family lives. In the collection of oral history recording database. National Archives of Singapore.

Vernon, J. (2007). Hunger: A modern history. England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Wong, H.S. (2009). Wartime kitchen: Food and eating in Singapore 1942–1950. Singapore: National Museum of Singapore and Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 641.30095957 WON).

Zhou, M. (1996). The life and family planning pioneer, Constance Goh: Point of light. Singapore: Graham Brash. (Call no.: RSING 363.96092 ZHO).

Notes

-

Malayan cost of living report. (1946, June 27). The Straits Times, p. 2. (Retrieved from NewspaperSG); Malayan Union. The wages and cost of living committee. (1946). The interim report of the wages and cost of living committee. Singapore: G.P.O. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 Jun 1946, p. 2; Malayan Union. The wages and cost of living committee. (1946). The interim report of the wages and cost of living committee. Singapore: G.P.O. ↩

-

Vernon, J. (2007). Hunger: A modern history (pp. 160–161). England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Vernon, 2007, pp. 181, 187. ↩

-

Tan, L. (Interviewer). (1984, April 17). Oral history interview with Tan Beng Neo [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000371/26/16, p. 249]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Wong, H.S. (2009). Wartime kitchen: Food and eating in Singapore 1942–1950 (p. 83). Singapore: National Museum of Singapore and Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 641.30095957 WON). ↩

-

Oral history interview with Tan Beng Neo, 17 Apr 1984; Wong, 2009, p. 83. ↩

-

Cheap lunch from today. (1946, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1947). Beginnings: The first report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare, June to December 1946 (p. 22). Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RRARE 361.6 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL28506). ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, pp. 23–24. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, pp. 23, 51. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 53. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 24. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 26. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 24. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 28. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare, 1947, p. 28. ↩

-

Big rush for 8-cents meal. (1946, December 19). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved form NewspaperSG. ↩

-

McNeice, 1983. ↩

-

35-cent lunch is a reality. (1946, June 28). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Governor eats and likes 35-cent lunch. (1946, June 30). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Jun 1946, p. 5. ↩

-

Alarm in the black market. (1946, July 13). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

All restaurants can sell 35-cent meal. (1946, July 12). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1946, July 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 16 Jul 1946, p. 4. ↩

-

Chinese Press runs 10-cent canteen. (1946, July 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

From a cursory scan of selected newspapers published in the same period, such announcements seemed exclusive to The Straits Times or The Singapore Free Press, with little to no similar announcements in rival newspapers such as The Malaya Tribune or the Chinese newspapers. ↩

-

Fernandes, O. (1947, March 12). Singapore did not starve. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2; Ikan bilis on the menu. (1946, October 21). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1946–1979). Annual report (p. 22). Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

S. E. Asia winning war on famine. (1947, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Forty-cent plate? (1946, August 15). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cheaper meals can be cheaper still. (1946, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

4½ million meals sold in S’pore. (1947, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 30. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 29. ↩

-

Restaurants to close. (1948, August 12). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1949, p. 34. ↩

-

Money before food. (1946, December 10). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Scheme to feed Singapore children. (1945, November 30). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 Nov 1945, 3. ↩

-

Feeding scheme to be enlarged. (1946, July 31). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1948). The second report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare 1947 (p. 33). Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RSING 361.6 SIN); Also announced in the press: New feeding scheme starts Jan. 2. (1946, December 30). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, n. p. ↩

-

Mr Attlee ordered free meals for S’pore. (1946, July 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lack of money for child feeding plan. (1946, November 23). The Straits Times, p. 5; see also Baby in a dust bin. (1946, November 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 10 Dec 1946, p. 4. ↩

-

Heavy expenditure criticised – Cost of new Singapore Departments. (6 September 1946). The Straits Times, 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 34. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 34. ↩

-

Volunteers run feeding centres. (1947, October 23). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

McNeice, 1982. ↩

-

McNeice, 1982. ↩

-

Zhou, M. (1996). The life and family planning pioneer, Constance Goh: Point of light. Singapore: Graham Brash, 133–135. (Call no.: RSING 363.96092 ZHO) ↩

-

See McNeice, 1982 and McNeice, 1983 for personal recollections of how Constance Goh established the association. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, pp. 20–21. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Social Welfare. (1949). The third report of the Singapore Department of Social Welfare 1948 (p. 4). Singapore: Department of Social Welfare. (Call no.: RSING 361.6 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 9. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Social Welfare, 1948, p. 9. ↩

-

See Axe may fall on feeding schemes. (1949, November 16). The Straits Times, 5; Scotching a rumour. (1949, December 20). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩ ↩

-

Welfare snacks will continue. (1950, September 14). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See Kratoska, P.H. (1988, March). The Post-1945 food shortage in British Malaya. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 19 (1), 27–47. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

3,500,000 meals in 2 years. (1948, August 14). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports. (2007). Helping hands, touching lives. Singapore: Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports. (Call no.: RSING 361.95957 HEL) ↩

-

Singapore, British Military Administration Chinese Affairs. (n.d.). Social welfare. [Long-term policy directive for Social welfare]. British Military Administration Chinese Affairs (27/45). Government Records Information database. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2010). Launch of Family Planning Publicity Campaign written by Lim, Irene. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

S’pore’s children get fed. (1947, February 3). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩