The Unlikely Composer: Tsao Chieh

Despite his untimely death at the age of 43, Singaporean composer Tsao Chieh’s legacy lives on — immortalised through his small but significant body of experimental works. Jun Zubillaga-Pow traces the life of this underrated artist.

Tsao Chieh working on a composition in 1986. Courtesy of Vivien Chen.

Tsao Chieh working on a composition in 1986. Courtesy of Vivien Chen.I prefer to listen to good Michael Jackson than bad Mahler.

Although hailed as a musical genius by his peers, Singaporean composer Tsao Chieh’s prodigious talents and legacy have been overshadowed by his untimely death at the age of 43. His accomplishments, unfortunately, have gone largely unnoticed by the general public, and this article is probably the first attempt at chronicling the composer’s life — from his growing-up years in Singapore, his musical forays during his engineering studies in Manchester and California, and his creative accomplishments in between juggling a high-flying military career on his return to Singapore.

Given the dearth of published sources on Tsao Chieh, this article pieces together material from the composer’s music manuscripts and newspaper articles as well as personal interviews with family members in 2010.

Early Years

Born on 27 December 1953, Tsao Chieh was presented with a toy piano at the age of three; his playful tinkering of the ivory keys at the time already an expression of his steely determination to become a musician. When he was six, his teacher, Theresa Khoo (丘秀玖), trained him to improvise on the piano. She would write different tunes, one of which Tsao Chieh recalled as a whimsical Malay tune about kachang puteh (white nuts). Growing up in Singapore during the 1960s, Tsao Chieh’s exposure to Western classical music was probably more extensive than his contemporaries.

His father, an engineer with the civil service, was a great fan of classical music and owned a vast collection of gramophone records. The family would play music in the house during breakfast and after work. It was amid this nurturing musical environment that Tsao Chieh’s affinity for music was cultivated. He gradually developed the ability to identify not only the different pieces, but also the performers on the records. After several years of studying the piano, it was discovered that Tsao Chieh had perfect relative pitch and, what was more, could differentiate pitches without using an instrument.

Tsao Chieh was already a proficient pianist by his early teens, acquiring a firm grounding of technical skills and musicianship. At 16, he came under the tutelage of well-known piano teacher and music critic Victor Doggett and achieved his Licentiate of the Royal School of Music (LRSM) in piano performance and Grade 8 qualification in theory. After topping his cohort at National Junior College, Tsao Chieh earned a Singapore Armed Forces Scholarship to study engineering at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology for the next four years.1

It was in Manchester that Tsao Chieh’s musical horizons broadened exponentially. In addition to assiduously attending performances in the English city, such as those by the Hallé Orchestra, he also signed up for orchestration classes conducted by the Music Department and perused numerous scores from the university library. Tsao Chieh also travelled to the English National Opera and Wigmore Hall in London, where he recorded many Radio 3 programmes from the BBC on cassettes and brought them back to Singapore.

Living in another country had widened Tsao Chieh’s cultural knowledge, but he could not be as involved with music as he would have liked during his subsequent three-year bond with the Ministry of Defence. In 1980, the unlikely composer obtained another scholarship to pursue his doctorate in Electrical Engineering at Stanford University. In California, in between his engineering studies, Tsao Chieh took up flute lessons, attended numerous concerts and extra classes in Mathematics and Music Composition. In an interview published by The Straits Times, Tsao Chieh said, “when I realised that with a little more effort I could get a Masters in Music Composition, I went for it.”2 Tsao Chieh’s musical accomplishments are all the more astounding given the fact he was in Stanford studying to be an engineer at that time.

In the five years that followed, the musical prodigy produced six pieces for flute and piano, a piano sonata as well as a larger work for soprano and chamber ensemble. On his own, Tsao Chieh devoted three years acquiring proper harmony and compositional techniques. He revealed that his writing was “very clumsy” when he first started attending classes, but he soon learnt to think outside the box, discovering “the importance of contrapuntal freedom … and the idea of rhythmic freedom” respectively from Leland Smith and Richard Felciano; the latter was then a visiting professor from the University of California, Berkeley. The notion of a “moving bass” was such a significant concept for Tsao Chieh that it would be mentioned over dinner conversations with his wife, Vivien Chen, whom he had met as a fellow student at NJC.

Early Compositions

From 1980 to 1982, Tsao Chieh’s three flute-and-piano pieces, Rondelay, Idyll and Toccata, secured prime positions in his foundational studies. While Rondelay, completed in September 1980, was dedicated to his flute teacher Alexandra Hawley, it was Toccata that received more performances at the university’s Dinkelspiel Auditorium between May 1984 and 1985. From 1982 to 1983, Tsao Chieh began work on an Overture in C for full orchestra, which has yet to be performed at the time of writing.

According to his widow, Tsao Chieh thought that writing in C major would be a good place to begin his first orchestral work. From his sketches, the initial title of the work was A Concert Overture. He drafted a first version on a four-staff short score, completing it in Stanford on 10 July 1982 and signing off after the double bar lines. The short score only had a few indications of where the French horns and percussion would play, while the full orchestration was duly completed eight months later on 8 March 1983.

In terms of stylistic originality, his music only took on a personality of its own in 1983. Borrowing from the French composer Henri Dutilleux, the choice of character pieces in his Movements for Flute, with Piano and String Quartet would be an indication of Tsao Chieh’s aesthetic preference for generic musical forms: the Intermezzo, Scherzetto, Cadenza and Ostinato. Unlike his earlier pieces, these allowed his musical imagination to be constrained within the emotional demands of the character pieces. As a trained engineer, it was natural that music became a less regimental outlet for Tsao Chieh to express himself.

In a similar vein, his Piano Sonata — which he personally performed at the premiere together with Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 109 and Debussy’s Images I at Stanford’s Campbell Recital Hall on 2 May 1983 — could be said as being inventive in its structural formulation and aesthetic direction. Of course, the piano recital would not have been possible without the encouragement of his erstwhile piano teacher Naomi Sparrow, who taught him the finer details of dynamics contrasts and other musical expressivity.

Being industrious, Tsao Chieh composed, in his final year at Stanford, a Caprice for two flutes and piano for another of his flute teachers, Carol Adee, promptly finishing the piece on 3 February 1984. Unlike his other works for flute, the work was the only one to receive a posthumous premiere in Singapore.

His next work was Four Songs from Romantic Poets for soprano and chamber ensemble, which was influenced by the writing style of Samuel Barber and Alban Berg, the latter being one of Tsao Chieh’s favourite composers. Similar to the Piano Sonata written a year earlier, atonal but romantic nuances could be discerned from this set of pieces. Four Songs, which won the first prize in the university’s Paul and Jean Hanna Music Composition Competition, was based on the 19th-century poems of William Blake (The Sick Rose), William Butler yeats (The Unappeasable Host) and Percy Shelley (The Waning Moon and Victoria). It was evident from this period that the perennial issue of musical communication between composer and audiences became one of the founding trajectories in Tsao Chieh’s creation process.

In the campus report of 24 April 1985, Tsao Chieh explained the decisions over the preparation for the performance: “I thought a singer singing in English would be a good thing for the audience to focus on… something for them to recognise… The themes are of night and storm, probably influenced by my great love of horror stories when a child”; as well as over the selection of some of these poems: “‘Victoria’ is about the ghost of a man’s murdered lover coming back to haunt him. I picked it because I wanted a nice, big ending. The poems I chose are actually quite perverse. There’s lots of percussion and rhythmically it’s very tricky. I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever written…”3

When his work subsequently premiered at the end-of-year Music Awards concert in May 1985, soprano Patricia Mikishka and conductor Chris Lanz, thought the piece was both “dramatic” and “contemporaneous”.

Music With a Singapore Spin

From 1984 to 1985, not only did the accomplished polymath work on his engineering PhD dissertation, he also composed and orchestrated his symphonic poem, which was given the grand title Singapore. The idea of composing a series of tone poems based on the history of Singapore had already been churning in his head for over two years after reading Constance Mary Turnbull’s A History of Singapore. It had been compulsory reading for the Ministry of Defence officer and the subject had surfaced in conversations over the dinner table. The engineer in him instinctively decided that each of the five movements of the suite would be based upon a specific period in Singapore’s history. The 40-minute work, Tsao Chieh explained in an interview, charts the chronological progress of Singapore from the pre-colonial era to the Japanese occupation to independent republic. He said, “It’s what I call an abstract work with symphonic unity… a cyclical symphony. Each section evokes a period in the history of Singapore. It will give an atmosphere, for instance, of Singapore before Raffles discovered it.”4

Aligned with his preference for classical forms, the five movements are based on the characteristics of generic symphonic movements with programmatic subtitles. The first movement is a prelude and Fugue, subtitled Temasek, while the second and third movements are a March and Scherzo, subtitled Colonial Days and War respectively. Music for the latter section was inspired by Seventy Days to Singapore by Stanley Falk, a telling of the Japanese invasion from Siam to Singapore. Before the Finale, which contains a quotation of the National Anthem as a proclamation of the new Republic, a Passacaglia is used to depict the cathartic Aftermath of the Japanese occupation.

Upon his return to Singapore, Tsao Chieh offered the composition to the Singapore Symphony Orchestra (SSO), which had premiered the music of Singaporean composers, such as Leong Yoon Pin, Bernard Tan and Phoon Yew Tien. The Singapore Festival of Arts in 1986 was fixed as an occasion for the premiere and the orchestra went about preparing the music; conductor Choo Hoey remarked that more musicians had to be engaged as a result of the composer’s large-scale orchestration. In addition to the usual array of orchestral instruments, Tsao Chieh requested for an alto flute, a bass clarinet, a double bassoon and a very large percussion section of six timpani, four tom-toms, chimes, vibraphone, piano harp and a water-gong. In accounting for his programming of the work, Choo Hoey quipped, “He’s young, up-and-coming and should be heard.”5

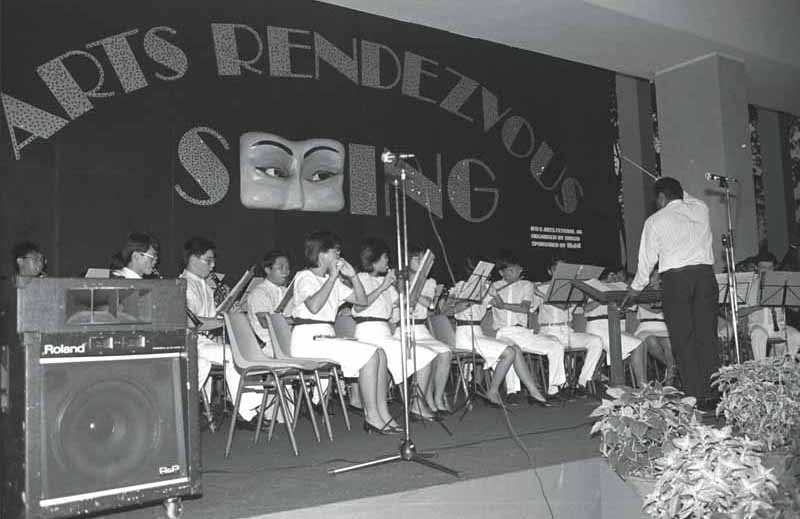

The student orchestra performing at the official opening of the 1986 Singapore Arts Festival at Kent Ridge. Tsao Chieh’s Singapore premiered on this occasion. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The student orchestra performing at the official opening of the 1986 Singapore Arts Festival at Kent Ridge. Tsao Chieh’s Singapore premiered on this occasion. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.When asked by an arts correspondent on his working process, Tsao Chieh mused about the concept of small beginnings, “An idea here. Another spark there. They can occur to me when I am brushing my teeth or going to sleep. Slowly, these fragments accumulate until they cohere to form a picture.”6

For two evenings in June 1986, the work, together with Joseph Haydn’s Cello Concerto and Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, was performed by the SSO at the Victoria Concert Hall. Stravinsky happened to be one of Tsao Chieh’s favourite composers. Responses to the symphonic suite ranged from the slightly disdainful: “a huge first novel, overstuffed with ideas” and “a hodgepodge of various styles” to the laudatory: an “imaginative handling of the orchestra” with “pastoral woodwind lending a tranquil mood over a gentle landscape of strings.”7 The piece was correspondingly broadcast on public radio twice and televised on the now-defunct Channel 12 for the next few months.

Citing Luciano Berio and Pierre Boulez as influences, the masterpiece also aroused interest from both music circles and general public. It provoked discussions on the definition of Singaporean music as well as the art of composition itself. Later, The Straits Times music critic Chang Tou Liang would recall that after listening to the masterpiece, he left the concert hall feeling proud to be a Singaporean.8 In September, Tsao Chieh was selected to represent Singapore as the Outstanding Young Person of the Year in recognition of his contributions to society and his leadership qualities.9

In 1988, Tsao Chieh, now a Lieutenant-Colonel with the Ministry of Defence, was commissioned by the Chief of Artillery, then-Lieutenant-Colonel Low Yee Kah, to compose a military march for the Artillery’s 100th anniversary celebrations.10 The Singapore Artillery Centennial March was performed by the Singapore Infantry Regiment Band on 22 February 1988 at the military parade at Khatib Camp with past and present Artillery soldiers as well as members of the public in attendance.11 The march was re-arranged the following year by Major Tonni Wei for the Singapore Symphony Orchestra’s concert performance under the baton of Lim Yau.

In March that year, a 12-minute piece was commissioned by the Singapore Youth Orchestra (SYO).12 Stasis (see text box), Tsao Chieh revealed, was a combination of two ideas, the “stillness and change” in the rhythms of Thai music and the “minimalist compositions of contemporary composers such as Philip Glass.”13 The composer qualified that although the work comprised only notes from the A major scale, it was still rhythmically complex and was without a constant meter. The work was given its maiden performance under the baton of Vivien Goh, who also programmed a Rossini overture, a Mozart symphony and a Beethoven concerto for the concert at the Victoria Theatre. While the SYO manager Tan Kim Swee felt Stasis was “contemporary” and “modernistic”, the composer preferred to call his work “minimalist”.

This characteristic of being “minimalist” can be readily discerned in Tsao Chieh’s Variations for Chamber Ensemble, which was programmed in the New Music Forum II under the direction of Lim Yau in January 1989. Tsao Chieh mentioned that the structure of the work was derived from that of Big Band Jazz, and includes several unique instrumental effects, such as pitch-bending flute, water gongs and playing inside the piano.14

In late 1990, his work Amidst the sough of winds…, Two Poems by Edwin Thumboo for Narrator and Large Orchestra was performed by the Singapore Symphony Orchestra on two December evenings. Preceding Max Bruch’s First Symphony and Peter Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, Choo Hoey conducted the premiere at the Victoria Concert Hall with the poet as narrator. In 1986, Tsao Chieh had expressed his intention to compose “a piece for narrator and orchestra based on the poetry of some local poets”, but he was unsure which poem would suit his aesthetics.15 Eventually, he found two relevant pieces from the literary anthology The Poetry of Singapore, which was published by the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, and fit the text to his music. He contemplated including a chorus, but was advised against the idea by the visiting British composer Alexander Goehr.

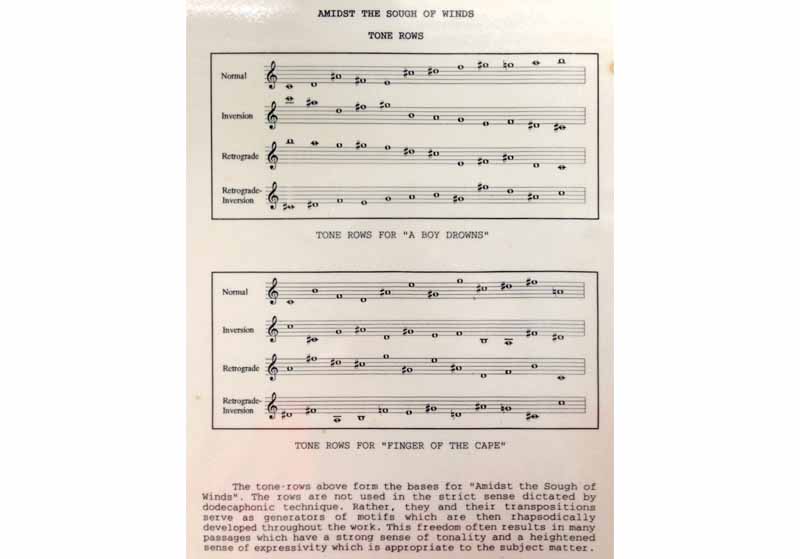

Tone rows for Amidst the Sough of Winds. Courtesy of Vivien Chen.

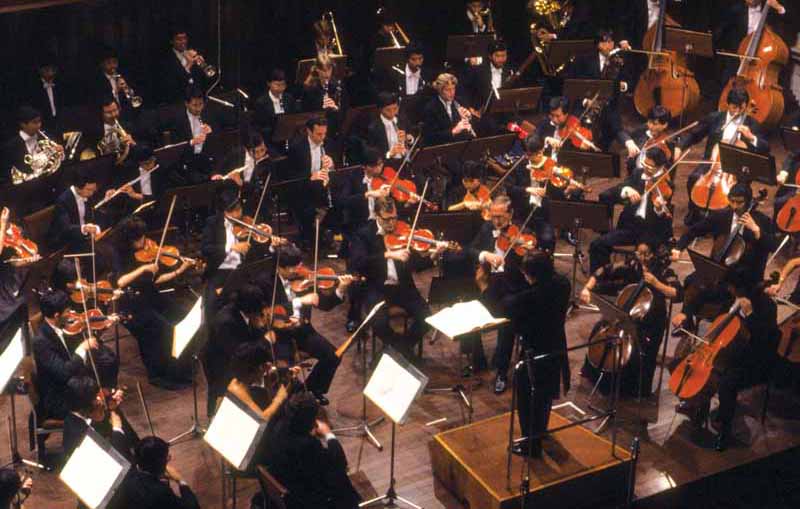

Tone rows for Amidst the Sough of Winds. Courtesy of Vivien Chen. Several of Tsao Chieh’s pieces were performed by Singapore Symphonic Orchestra performing at the Victoria Concert Hall under the baton of Choo Hoey. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Several of Tsao Chieh’s pieces were performed by Singapore Symphonic Orchestra performing at the Victoria Concert Hall under the baton of Choo Hoey. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Computer Music

In 1992, Tsao Chieh was featured in a news report about electronic or computer music. He had gradually progressed from using computers for music typography in 1986 to composing directly at the computer in 1992. He explained that “the hardest part is mastering the software programme, which is very complex. The learning curve is steep. You only become proficient after six, seven months or more.”16 Sceptics would probably say that the task was a walk in the park for someone with an engineer’s mind and a proclivity for learning.

His next work for the Singapore Youth Orchestra was composed directly on the computer, which enabled him to play back the music as synthesised sounds and make necessary changes. The commissioned work, Prelude, Interlude and Fugato, was performed in part under guest conductor Chan Tze Law on 24 July 1992 and only in full two years later under the baton of Lim Yau on 26 March 1994.17 Both Tze Law and Lim Yau agreed that the music was a tad difficult for the youth orchestra, which resulted in longer rehearsal times. The Singapore Symphony Orchestra performed the work on 16 January 1998, two years after Tsao Chieh’s passing.18 Hearing only the final movement of the three-part composition, The Straits Times critic Philip Looi noted that Tsao Chieh’s “rich instrumentation and often dense texture” were kept in good control by Tze Law, and that “the tuneful diatonic passages were played with a broad legato articulation that contrasted well with the strongly articulated 12-tone fugato sections.”19

Tsao Chieh had been experimenting with recorded sounds by uploading them into the computer and manipulating them to create brand new sounds since 1992. He wanted to not only compose computer-generated works, but also to emulate composers who wrote computer programmes. He optimistically believed that “the range of sounds that the computer [could] create [was] only limited by the imagination”, but the pragmatist in him acknowledged that he had to develop “his computer knowledge and technique first.”20 For the time being, however, the avid audiophile thought he might inject some of the computer generated sounds into his “traditional classical compositions.”

Gradually, what came out of the germination process were three test pieces, a rhapsody for synthesised flute and a more substantial composition entitled Sine. Mus. Although all these electronic pieces were believed to be completed by 1995, the actual period of production and completion remain uncertain. In May 1994, the commissioned work Two Little Pieces for Orchestra premiered at the Victoria Concert Hall conducted by Chan Tze Law and played by the Temasek Junior College Orchestra. The two relatively neoclassical pieces in diatonic modes came with the titles Idyll and Dance; according to the composer, he had always wanted to write them since he was a teenager, but lacked the technical know-how.

Tsao Chieh’s Two Little Pieces was performed again the following year by the National University of Singapore Symphony Orchestra at the university’s 90th anniversary celebrations. It was conducted by Lim Soon Lee this time round at the Victoria Concert Hall. In early 1995, Tsao Chieh set the poem Old House at Ang Siang Hill by Singaporean poet and Cultural Medallion winner Arthur Yap to music for soprano and piano.

Sadly, on 27 October 1996, Tsao Chieh passed away from liver cancer just two months shy of his 43rd birthday, leaving behind his wife and two young children. At the time of his death he had left the military and joined Sembawang Corporation as Special Assistant for Technology but all this while he remained active in local arts circles as a member of the National Arts Council (1993) and management committee of the SYO, chairing the music panel for the 1994 Cultural Medallion awards.

Despite his varied body of work, Tsao Chieh had always lamented that composers remained at the mercy of others. He said, “Of all the different artists, it is quite terrible to be a composer, because your dream has to be realised by other people.”

Photograph of Tsao Chieh taken in 1990. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph of Tsao Chieh taken in 1990. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission.

MAKING WATER MUSIC

The Singapore Youth Orchestra brought one of Tsao Chieh’s works Stasis on tour to Perth, Australia, in June 1988. The general manager of the orchestra Tan Kim Swee21 remembered the piece required a water tank, one “big enough to immerse a big gong”. The story was that the first tank that had been acquired was too small for the gong and a second one had to be custom-made for the piece. This must have been so stressful for Tan that he even remembered the precise dimensions of the tank — 50 centimetres in breadth and length and 100 centimetres in height — which was to be filled with water as instructed by the composer. Tan recalled the ensuing frenzy over how the water tank had to be filled exactly to four-fifths of its height using buckets and subsequently emptied the same way before and after each concert. During both the local and Australian performances, the tank was placed at the back of the orchestra but elevated so that it remained visible to the audience. Tan also recalls clearly that the commissioned work required bamboo chimes and glass chimes, both of which had to be custom made.

REVIEWS OF TSAO CHIEH’S MUSIC

Under the baton of Lan Shui, the Singapore Symphonic Orchestra recorded three compact discs of Tsao Chieh’s orchestral works. In his review, Chang Tou Liang considered the composer to be a “modern-day Charles Ives, one who composed in his spare time.” He said:

“The impressionism of Debussy and Ravel, pomp and circumstance of Elgar and Walton, serialism of Schoenberg and the passacaglia-writing style of Shostakovich are all evident, mixed with a healthy dose of melody — Rasa Sayang, Xiao Bai Chuan (Little Sailboat) and one big tune of his own device.”22

In her review on Tsao Chieh’s electronic music, the ethnomusicologist Tan Shzr Ee said that it does “lovely things to your ear.” She elaborated:

“It is a treasure box of weird and delightful sounds either simulating acoustic instruments to eerie effect, or churning out frenetic blubs of nonsensical noises which must surely carry abstracted meanings in their own right…

“Just when you think you have nailed the composer to a pastiche of Debussy or Bartok-styled chromatic harmonies, a tinkly horror-movie soundtrack surges into your hearing, stealing your breath away. Small and sparse jumbles of sound are thrown away here and there against a backdrop of tense calm created by near-silent electronic ‘whooshes’.

“Sometimes, a woman laughs and a man snatches the space for his moment with a scramble of words. Themes which sound transplanted from a drama-mama Chinese opera groove against a dizzying spiral of unremitting notes. It is a trippy and absolutely mesmerising experience.

“But every now and then, a curious refrain of a decaying, owl-like ‘woo’, flattened out in pitch towards its tail, rears up like a leitmotif. It reminds you of the constancy of — work? everyday existence? the inner rhythms of life? — that punctuate this album’s otherwise over-the-top splendour.”23

Jun Zubillaga-Pow is a PhD Candidate in music research at King’s College London. He has performed and curated music events at the Esplanade, the Arts House, Theatreworks and the Substation. With the support of the National Arts Council, Jun is the co-editor of Queer Singapore and Singapore Soundscape.

REFERENCES

11 vie for best of youth title. (1986, September 4). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chang, T.L. (1998, September 18). Too much to ask of Schweizer. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Chang, T.L. (2001, December 7). A symphony with sound of Rasa Sayang? The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Cheah, P. (1986, February 6). Soldier composes a Singapore suite. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspapersSG.

Chua, R. (1986, February 15). Our history in music. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Concert tribute to Singapore composer. (1998, January 15). The Straits Times, p. 79. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Emmanuel, G. (1986, June 16). Romantic touch of Haydn. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Gunners plan big bang for centenary celebrations. (1988, February 9). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

It sure beats chicken-scratch. (1992, June 9). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lim, H.F. (1988, March 19). A young pianist’s Sunday treat and a composer’s static work. The Straits Times, p. 39. Retrieved in NewspaperSG.

Looi, P. (1992, July 22). Music notes. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Looi, P. (1992, July 27). Rich, controlled performance. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Phang, M.Y. (1994, March 23). Music notes. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sasitharan, T. (1989, January 9). Local composers merit patronage. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Sng, S. (Interviewer). (2006, March 28). Oral history interview with Tan Kim Swee (Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002992/34/27, pp. 713–738). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Stanford University. (1985, April 24). Campus report. Retrieved from Stanford University website.

Tan, S.E. (2002, February 1). Electrifying electronica. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Top HSC pupil: Two in the running. (1972, March 6). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Yap, M. (1988, February 23). SAF chief tells of challenges. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Top HSC pupil: Two in the running. (1972, March 6). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cheah, P. (1986, February 6). Soldier composes a Singapore suite. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspapersSG. ↩

-

Stanford University. (1985, April 24). Campus report. Retrieved from Stanford University website. ↩

-

Chua, R. (1986, February 15). Our history in music. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 6 Feb 1986, p. 32. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 6 Feb 1986, p. 32. ↩

-

Emmanuel, G. (1986, June 16). Romantic touch of Haydn. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chang, T.L. (1998, September 18). Too much to ask of Schweizer. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

11 vie for best of youth title. (1986, September 4). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gunners plan big bang for centenary celebrations. (1988, February 9). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yap, M. (1988, February 23). SAF chief tells of challenges. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sng, S. (Interviewer). (2006, March 28). Oral history interview with Tan Kim Swee (Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002992/34/27, pp. 713–738). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lim, H.F. (1988, March 19). A young pianist’s Sunday treat and a composer’s static work. The Straits Times, p. 39. Retrieved in NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sasitharan, T. (1989, January 9). Local composers merit patronage. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 15 Feb 1986, p. 13. ↩

-

It sure beats chicken-scratch. (1992, June 9). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Looi, P. (1992, July 22). Music notes. The Straits Times, p. 5; Phang, M.Y. (1994, March 23). Music notes. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Concert tribute to Singapore composer. (1998, January 15). The Straits Times, p. 79. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Looi, P. (1992, July 27). Rich, controlled performance. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 9 Jun 1992, p. 2. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Tan Kim Swee, 28 Mar 2006. ↩

-

Chang, T.L. (2001, December 7). A symphony with sound of Rasa Sayang? The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, S.E. (2002, February 1). Electrifying electronica. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩