A Peek into the Lives of the “Lancing Girls” Cabarets, Charity and Cheongsams

By Adeline Foo

Introduction

Who were the so-called “lancing” girls1 of yesteryear? They were the glamorous dance hostesses from the cabarets of the “big three” worlds of entertainment in Singapore’s past – New World, Great World and Happy World – who made a living from “lancing”, a Singlish mispronunciation of “dancing”. This paper examines the way of life of these women in the cabaret industry, with a focus on two of them who founded The Happy School, a Chinese school that provided free education for street kids after World War II . In a bid to regain their pride after having been being looked down on for working in the cabaret, the “lancing girls” are shown here to have contributed generously to charity. Speaking to four research subjects in their 70s and 80s who had once been associated with the cabaret, we trace the beginnings of Singapore’s nightclub dance scene, observe the rise of pop music and the evolution of the cheongsam as a “lancing” dress. The unadulterated accounts of the lives of these people offer a candid look at Singapore’s unique history through the glitz (and sleaze) of the New, Great and Happy Worlds.

Background of the Cabaret World

The New World Amusement Park was the first to open in 1923 at Jalan Besar. Great World Amusement Park at Kim Seng Road opened next in 1931. Happy World, located between Mountbatten and Geylang roads, was the last of the three to open, in 1936. Its name was changed to Gay World in 1964 when cinema operator Eng Wah took over the ownership.2

These parks were similar in their entertainment offerings, which included shopping, film-going and dining. But what really drew the crowds were the dance halls or cabarets. New World was famous for Bunga Tanjong, a cabaret that hosted bands playing Malay tunes and ronggeng (a couple dance likely to have originated from Java, also known as joget). Great World attracted British servicemen and the middle class, with free films, Peking operas as well as wrestling and boxing matches. Happy World was known for its Sarong Kebaya Nights at the Happy Cabaret.3

During the war, all three worlds were converted into gambling farms. After the end of the Japanese Occupation, western music could once again be heard in Singapore. The cabarets resumed happy times, drawing young girls into their dance halls to work and help their families put food on the table. Single men, married men, couples and groups of people seeking after-dinner entertainment all came trooping back. Bands comprised quartets, trios or a hotchpotch of music lovers forming dance bands.

The repertoire of music ranged from Broadway to those by famous composers such as Cole Porter and George Gershwin, to the music of the swing era; anything that would draw in the masses – even local music played by keroncong (an Indonesian musical style) bands – filled the air of dance halls. Some of the more popular big bands included those led by Cecil Wilson, Gerry Soliano, H.H. Tan and Peggy Tan, Sid Gomez and Alfredo (Fred) Libio, who had his “all-star” Filipino Swing Band.4

Working in the Cabaret in the 1940s and 50s

So why were women drawn to work in the cabarets? Were they not afraid that family and friends would frown upon their choice of work? My search to speak to a former cabaret woman proved serendipitous when I encountered a man operating the photocopier at one of the public libraries. He was once a customer of the cabarets, and was still in touch with some former cabaret women. When I told him I was working on a research paper about them, he gave me the contact of Wong Siew Wah. The second woman I met was Wong’s cousin, Ong Swee Neo.

Ong, 75, recalled: “It was 1952. I only studied until Standard 2. I was 12 years old when my mother brought me into the cabaret.” When probed, Ong did not seem ashamed that she was 12 when she was brought into the cabaret. “The money was good. My mother kept all my earnings. All I had to do was sit, chat and dance. I was big-sized. No one could tell my real age. Customers were kind. They never forced me to drink hard liquor. I would only drink Green Spot or Red Lion orange crush”.5

Wong, 69, said, “My adoptive mother, Nancy Ho, worked as a ‘Mummy’ in the cabaret. Her job was to look after the ‘lancing’ girls under her and make sure that the clients did not try any funny business. These girls were also known as taxi dancers or mou luei in Cantonese. What I remembered about them was that they were tough women who had to adapt to hard times”.6

Further research into articles on the cabaret women made me realise that life for the “lancing” girl wasn’t all hunky-dory. An average cabaret girl could expect to earn about $200 a month, although the more popular girls had been known to bring home $1,000 a month. In comparison, a senior clerk working in the government in 1952 earned about $280 a month.7 For just about anyone back then, earnings of $1,000 a month was a lot of money!

Cabaret girls were easily hired and fired. They had to be mindful of cabaret etiquette and cultivate good customer relations. Discipline and patience were vital for survival. Working from 6 pm to past midnight daily at the rate of one dance every three minutes, girls were expected to know their music and dance steps. A quick change in tune meant slipping from the foxtrot or quickstep into the ronggeng or joget. If hired to sit at a table for $13 an hour, the girl was expected to hold her liquor while drinking with four to six customers. Girls professed to be able to throw up in 30-minute intervals, and return to the table to keep on drinking. The worst bit of working in a cabaret was when a jealous wife or girlfriend showed up to create trouble – the toilet was the safest place to seek refuge.

In the first meeting of the Singapore Cabaret Girls’ Association held in 1939 at Great World, 180 members were warmly welcomed – the real test, however, was realising “a potential membership of 500 girls”.8 The early batch of mou luei (meaning dancing girl in Cantonese) hailed from Shanghai and Hong Kong; they too had been members of similar associations. What could a member expect from the Singapore Cabaret Girls’ Association? Strength in numbers and, more importantly, a united voice in fighting for the right to be treated with respect.

Exactly 10 years later, in 1949, membership figures at the Association stood at 600. When I asked Wong what she recalled of her mother, she said, “She was very active. She was always looking out for the girls.” As chairperson of the association, Ho had fought for her girls to receive a tax deduction of $125 a month “to keep up good appearances essential to their profession”.9 The amount represented about 15 percent of their total earnings. This was unusual as the tax relief would have meant an official acceptance of the Association’s recommendation that the girls’ “dresses, shoes, hair setting and cosmetics” were an allowable deduction.

Following this, Ho successfully lobbied for the Association to change their name to Singapore Dance Hostesses’ Association, which was a more accurate reflection of what they did. In addition, she raised money for the purchase and furnishing of a clubhouse at Lorong 10 Geylang, which cost close to $15,000, for use by her dance hostesses.10

When I asked Ong if she missed the glitzy world of cabaret after her fiancé forced her to leave, she said no, adding: “We were poor, I had little education. My mother was also a cabaret girl, [and] it was the only job I could do. Once I left, I never looked back.”

So what was life like for Nancy Ho and Ong Swee Neo after they left the cabaret?

Ho found love and married a man she met at the cabaret; they adopted three children, two girls and a boy. She also converted to Catholicism. Ong married her sweetheart and had five children. Today, she is a grandmother of 11.

An Infamous Cabaret Girl Turned Striptease Dancer

Many people I spoke to about cabaret life wanted to talk about the most famous cabaret striptease dancer of the time, Rose Chan. And although there was grudging respect for Chan’s daring to strip fully, the person commenting would invariably call her an impolite term.

Chan had married at 16 to a much older man. After her marriage failed, she turned to the cabaret for a job at Happy World. She taught herself to dance and was a quick learner. She finished runner-up in the All-Women’s Ballroom Dancing Championships in 1949 and was also runner-up in the Miss Singapore Beauty Contest in 1950.11 Chan’s colourful life attracted a great deal of attention in the 1950s. She was known as the “Queen of Striptease” for her sensational acts, which included a circus stunt known as the “Python Act” where she would wrestle with a python.

In August 2008, Singapore theatre group The Theatre Practice staged I am Queen, a play that told the story of stripper Betty Yong, a character modelled after Chan. A biopic of Chan’s life, titled Chinese Rose, was to have been directed by Eric Khoo..12 Leading actress, Christy Yow, had been cast, but for reasons unannounced, the project was called off by late 2009.

The third person I interviewed was Chan’s boyfriend, Edward Khoo, 85. He had known Chan for five years in the 1950s. He wistfully recalled that Rose was a feisty character. She loved to dance, she loved music, and she never backed down from a challenge. “She was very popular in the cabaret,” he said. “I had heard about her, and I wanted to meet her. I finally got the chance. After I got to know her well, I asked her to be my girlfriend. She agreed and I put her up in a house in 40F Lorong Melayu at Sims Avenue East. But we were never married as my parents objected to our relationship”..13

I spoke with Khoo for almost an hour and his face would light up each time he mentioned the cabaret and his relationship with Chan.

Cabaret Girls and Their Hearts of Gold

Dancing was not all that the cabaret women did. Not many people are aware that they were also involved in charity. In a report dated 27 August 1953 in The Singapore Free Press, an amount of $13,000 had been raised by the Singapore Dance Hostesses’ Association in aid of the Nanyang University building fund..14 The funds were raised through the staging of several charity night performances. Rose Chan was part of the act that raised this huge amount of money. Her generosity earned her the nickname “Charity Queen”. She would donate to charities, including those benefiting children, old folks’ homes, tuberculosis patients and the blind.

But Chan wasn’t the only “Charity Queen” in the cabaret world. There were also two other women who had piqued my interest: the founders of The Happy School that once stood in Geylang, He Yan Na and Xu Qian Hong.

The Happy School

In 1946, local cabaret girls from Happy World in Geylang answered the call from one of their “big sisters”, He Yan Na, to donate money to set up a Chinese-medium school. He, the chairperson of the Happy World Dance Troupe (which later became Happy Opera Society), had been deeply troubled by the large number of idle children roaming the streets of Geylang. These were the unfortunate children who had had their education interrupted by the war.

He roped in her fellow dance hostesses to set up the school. She became the chairperson of the school’s board of governors, and another dancer, Xu Qian Hong, was recruited to be the accounts head. Other girls from the Happy Opera Society became board members.

Determined that the children should receive a free education, He insisted that no school fees would be collected from the families. Whatever books and stationery the children needed would be provided free. The first enrolment in 1946 attracted about 90 students. Operating out of a rented shophouse at Lorong 14, He named the school “Happy Charity School” in an obvious nod to the most popular landmark in Geylang then – the Happy World amusement park..15

The first principal of the school was Wong Guo Liang, a well-known calligrapher. When Wong first met He at the interview for the position, he related how he had been struck by her charisma and generosity. She in turn advised him that as a principal, he had to set a good example and live up to the responsibility of being a role model for his charges and should never visit the Happy World Cabaret. He also related how her impoverished past, which led to her missing out on an education, made her determined to help the children. Education would give the children the means to do something worthy with their lives..16

Giving insight into how He viewed her position as a cabaret dancer, she frankly shared her frustration that “the profession of dancing girls is seen as inferior. If society can abandon its prejudice and be rational, they would understand that they have misunderstood the art of dancing. They are being cruel to cabaret girls due to their ignorance. If dancing is corrupt, then this negative image comes not from the dancers, but the vice that tarnishes the environment. To punish and shame the girls is ridiculous”..17

The co-founder of Happy Charity School, Xu Qian Hong, was a great beauty with a generous heart. An article in the Nanyang Siang Pau dated 10 June 1947 described her as “enchanting” and “energetic” by turns. A Cantonese, Xu became a cabaret girl at 16 to help her father support her younger siblings after the death of her mother. She only had two years of Chinese education at the time. A widely sought-after cabaret girl, Xu earned about $1,000 a month; from out of her own pocket, she would donate about $500 each month to help the school defray its expenses..18

What the two women and their comrades did was admirable in the context of the urgent need to keep children off the streets. An article in The Straits Times dated 23 November 1947 declared that “Singapore Needs More Schools”. The number of children in need of schooling had increased because of the interruption of the Japanese Occupation. There were approximately 90,000 children of school-going age..19 The situation was made worse by the fact that there were not enough teachers, and a shortage of books. During the Japanese Occupation, the Japanese had targeted the Chinese for the most severe and cruel treatment. Anti-Japanese imperialist campaigns led by the Chinese community and Chinese schools in Malaya throughout the occupation had ensured their persecution. Chinese schoolteachers were systematically targeted during the Sook Ching (“ethnic cleansing”) massacre, with many taken away and killed. Chinese books were also not spared. An estimated 200,000 books were destroyed by the Japanese during this period.20

In the face of this dire situation, He and Xu became actively involved in the running of the school from 1946 to 1950. With increasing challenges such as rising costs and the need to recruit more teachers, the school implemented a school fee of between $2.50 and $3.50 per student in January 1950. Following this, the Happy Charity School relinquished its “free” status and renamed itself The Happy School.21

For unknown reasons, the two women left the school after this period. Their whereabouts were untraceable, although a search in the Chinese press revealed a controversial court case that involved Xu, over the purchase of a female child whom she had wanted to adopt.22 In my interview with former cabaret girl Ong Swee Neo, I learnt that there had been a general acceptance back in the day for unmarried cabaret women to adopt young female children to be groomed as cabaret girls. I assumed that these girls would then be expected to take care of their adoptive mothers after their retirement from the cabaret world.

The Happy School operated out of Geylang from 1946 to 1979. It moved once in 1947, from Unit 24 on Lorong 14 to Units 67 and 69 along the same lane, after receiving financial help from George Lee, the owner of Happy World.

In 1946, The Happy School started with 90 students. By 1959, its enrolment had ballooned to about 600 students. Due to insufficient space at its Geylang premises, some lessons had to be conducted out of two rented classrooms at the Mountbatten Community Centre.23

Unfortunately, in the 1960s and 1970s, the school experienced a similar trend seen across all Chinese-medium schools in Singapore. As Singapore’s economy shifted towards industrialisation and English became recognised as the de facto working language, more and more parents decided to send their children to English-stream schools. Dwindling student numbers at Chinese-medium schools islandwide eventually sounded the death knell for The Happy School.

In 1979, the school announced its closure. By that time, The Happy School had amassed $400,000 in savings, which it donated to 10 Chinese schools and grassroots organisations.24 After 33 years, The Happy School closed a chapter in the history of free schools for children in Singapore. Without a doubt, its inception was graced with a touch of glamour (and controversy) by cabaret women. Yet, were it not for the founders He and Xu, many of these destitute children would not have had a primary school education in post-war Singapore.

Further Research into the Lives of Cabaret Girls

Being a cabaret woman back in the day came with some form of social stigma attached. In three letters that I came across, addressed to the Chinese news daily Nanyang Siang Pau in 1937, 1938 and 1976, the writers, all cabaret women, shared candid reflections of their lives. The first letter in 1937 sought to paint an accurate picture of cabaret girls, placing them into two categories. The first comprised girls with mediocre dancing abilities but who were able to engage customers easily because of their looks and feminine wiles. These girls were very popular with older, rich men who were liberal with their wallets. The second category of girls were excellent dancers. Though not very pretty, they prided themselves on doing their jobs professionally, which meant dancing and giving their customers an enjoyable time. These girls usually drew younger men, mostly students.25

The 1938 letter lamented the working conditions of cabaret women: long working hours in close confines with large crowds, and being often “manhandled” by customers. The women would fall sick easily, contracting illnesses such as typhoid fever (characterised by fever, diarrhoea, headaches and intestinal inflammation). When admitted to the hospital, they could only stay in third-class wards, the cheapest form of medical care available, as the dance halls that employed these girls made no provision to help them financially.26

The 1976 letter shared a brutally honest account of cabaret life: beneath all the glitz and attraction of the cabaret, life was tough. To survive, the women had to be extremely wary of their customers. These men could be businessmen or secret society members, and offending the wrong men would mean trouble. To stay popular, girls were expected to be welldressed and to look beautiful. They had to have a demure disposition and be accommodating and caring. Girls had to learn to be subservient to the needs of the customer; it would help if they were eloquent or were adept at socialising. When it came to money or gifts, the writers claimed that very few girls would be able to reject them. Some girls became mistresses (kept women) of their customers. This was something affirmed by Rose Chan’s then-boyfriend, Khoo, during my interview with him. The letter ended with the remark that “the ugly profession of the cabaret girls is an open secret; mai yin (卖淫) [to prostitute oneself for money] is a commonly accepted practice”.27

So if working in the cabaret subjected women to prejudice and numerous “sacrifices”, why did they take on such jobs? To answer this question, let’s take a look at the jobs that were available for women back in the 1940s.

The Lot of Women in the Past

In 1948 when the National Registration Ordinance was passed, the National Registration Office (NRO ) of the colonial government began issuing paper ICs (identity cards) to identify individuals born in Singapore. Women signed up as clerks to help with the registration process. At a rate of $6 a day, they reported for work in the writing section of the NRO Headquarters at Beach Road, filling out particulars of individuals to process their new ICs. In an article published in The Straits Times on 30 October 1948, it was stated that up to 300 women were on the payroll to perform these tasks. Work started at 8am and went on until 5pm, with 15-minute breaks every two hours to provide relief. A large proportion of the 112 female clerks doing this registration job were cabaret girls who needed a day job to supplement their earnings from the cabaret.28 Besides the cabaret girls, there were also European and Eurasian housewives, as well as girls who had just left school. Filling out 160 cards a day, the girls knew that it was only a temporary job that would end once the NRO achieved its target to issue all ICs. What else could women do then?

There were alternative jobs, such as working as barbers. In a Straits Times article dated 23 October 1949, titled “Kindest Cut by Women Barbers”, an estimated one-third of about 2,000 Chinese barbers were young women. But the job of a barber was not easy. An hour’s schedule of service involved hair clipping, shaving, shampooing and ear cleaning. Tending to an average of 50 heads a day, the female barber had to be on her feet for 15 hours daily. They would only get to keep 70 percent of their takings if they lived on their own; if they were boarding with their salon proprietors, they would only get to keep 50 percent, with the balance used to pay for food and material costs.29

The average salary for a female barber was about $100 a month, a pittance compared to working in the cabaret. From 1955 to 1959, other jobs that were available to women included working as seamstresses, sales assistants, tour guides, singers in the dance halls and restaurant waitresses. If a girl was educated, she could consider becoming an office secretary or a private tutor. Objectively, these jobs did not pay as well as that of a cabaret dance girl. So if a woman needed cash urgently, cabaret dancing provided a means to quick and good money.

Most of the cabaret girls probably thought they could take care of themselves. But Khoo and Wong shared that it was easy to be led astray; they knew of cabaret girls who had become pregnant on the job. But because they wanted to keep on dancing, they risked their lives when they chose to undergo abortions. In an abortion, complications could arise, such as getting lacerations in the womb or being left with an incomplete, septic abortion that could lead to severe infection. There were legalised clinics to turn to, such as the “well-known” clinic in Geylang managed by a Dr Harold Chan who was quoted as one that women turned to. But sometimes, these girls turned to cheaper alternatives to terminate their pregnancies, such as unlicensed medical workers or private midwives, which sometimes led to disastrous consequences.

Of course, it is not fair to generalise all cabaret women as “unchaste”, for want of a better word. But the negative perception towards these women was something difficult to shake off, as seen from this former cabaret customer’s experience:

Happy World Cabaret was the most popular one among the

three amusement parks. The cabaret girls would live near their

workplace, so for those working in Happy World, they would live

in Geylang. I would visit the cabaret five, or up to six, times a

week. I was working as an engineer in the late 1930s; I had a car,

so I could drive my friends around. Most of the customers attracted

to Happy World were the Europeans. The band was really good,

a Filipino one.

When the Navy officers from America and Britain were on shore

leave and came to visit the cabarets, fights would break out,

usually over the choice of dance partners. One of the regulations

of the cabaret was that a girl could not refuse a dance. She could

complain if the customer was abusive or difficult, but she couldn’t

say no. These girls were allowed to be booked out when “Mummies”

came into the picture. They controlled these girls, where they lived,

what they ate, et cetera.

When the “Mummies” said the girls could leave the cabaret,

usually near closing time, the girls would be booked out an hour

before they left the cabaret, and this was when prostitution started.

These “Mummies” would take a cut from the booking ($2 out of

$12 an hour, this was the rate after the war). The standard of the

cabaret dropped when [the] more respectable girls left the cabaret

because of this.30

If the cabaret girls were expecting, they would find it hard to continue working, so they would usually choose to terminate the pregnancy. In the 3 November 1962 The Straits Times article “Victim of An Abortionist Takes Secret to the Grave”, it was apparent that there was a veil of secrecy surrounding the subject of abortions, even to the extent of shielding the identities of medical workers who conducted such procedures on the sly. In this case, a 34-year old bar waitress, Gertrude June Pinto, refused to reveal the name of the medical worker who had operated on her. Complications from the botched operation led to tetanus, which eventually took her life. This was not Pinto’s first operation by the same man, and it was revealed that the clandestine operation had been performed in the “staff quarters” of the General Hospital at New Bridge Road.31

Another article in The Straits Times, “Bar Girl Tells of An Abortionist, Then Dies”, dated 21 December 1962, reported that 21-year-old Lim Ai Choo went to a woman who ran a private maternity service in a garment shop at North Bridge Road. Lim paid $100 for the abortion, and was rushed to Kandang Kerbau Maternity Hospital when problems arose. Despite an emergency operation to save her, she died.32

Besides losing their moral compasses, the cabaret girls were also subjected to another harsh reality of the job – losing their appeal to customers as they advanced in age. On 5 October 1972, the New Nation ran a four-part report, headlined “Glamour Only a Façade”, on the lives of cabaret girls, stating that “age is a hard fact of a cabaret girl’s life. The older she gets, the less marketable she is. The old and unsuccessful usually turn to full-time prostitution. Only about 5 percent marry and settle down to security and a home of their own”.33

The Glamour of a “Lancing Girl”

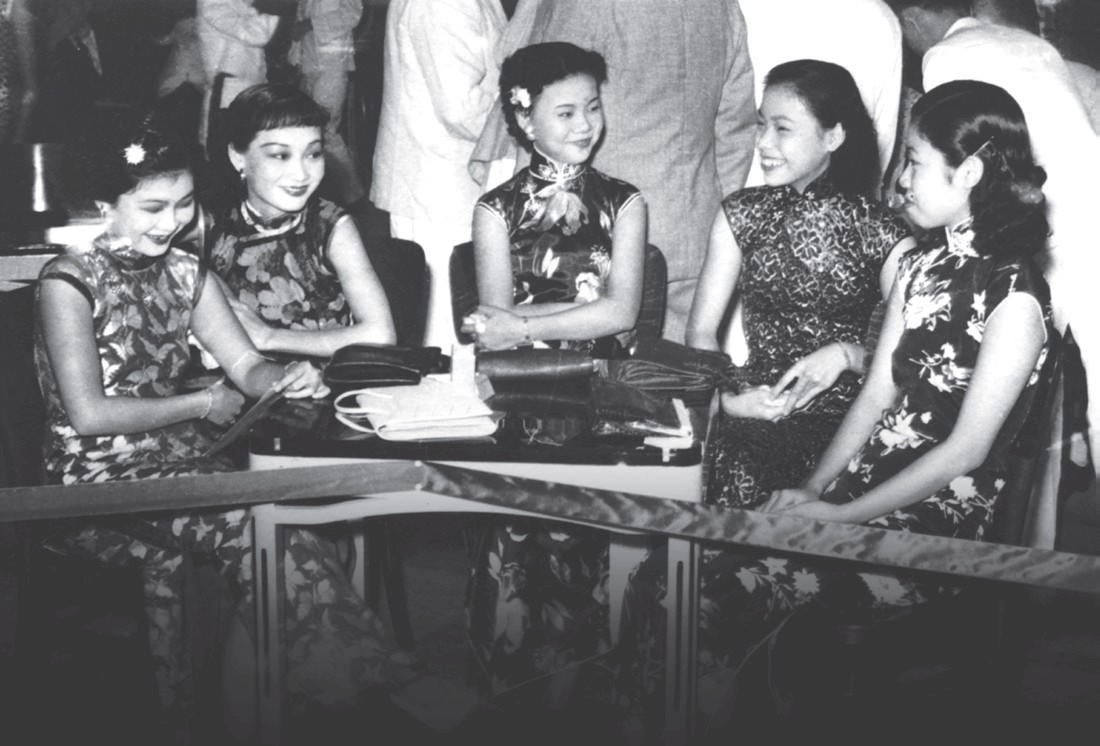

Much has been said about the tough life of a cabaret girl. On a lighter note, let us look at the glitz associated with the cabaret. In particular, I was interested in seeing how cabaret girls dressed from the late 1920s to 1960s. Looking good and being well-groomed for the job meant spending on clothes, hair and cosmetics. Advertisements and pictures from newspapers provide a peek into the fashion of these cabaret girls.

Like most women in Singapore, cabaret girls were probably influenced by fashion trends featured in entertainment magazines. They naturally looked towards Shanghai and Hong Kong for inspiration, as these cities were acknowledged as the leading fashion capitals of the time.

What did Chinese women wear back in the 1920s? The samfoo (or samfu) was the preferred casual attire, comprising a short-sleeved cotton blouse with a Mandarin collar and frog-buttons, with a matching pair of trousers in the same material, which was usually pastel, printed cotton. By the 1930s, women in the upper social classes had turned to the cheongsam, or qipao in Mandarin, as their preferred dress. This trend soon cut across all sectors, with the cheongsam being worn as a symbol of strong feminine expression. After World War II , more women turned to wearing western clothes, but there were those who remained faithful to the traditional cheongsam, preferring its tighter fit. But due to influences from the west, the cheongsam was embellished and accessorised in line with European and American trends.34

For Straits Chinese (Peranakan) women, or nonyas, the sarong kebaya became increasingly reserved only for special occasions, such as weddings. However, older Peranakan women still wore the outfit on a daily basis, throughout the 1950s up until the late 20th century.35

With the influx of Cantonese and Shanghainese tailors who set up shop along Orchard Road, High Street, North Bridge Road, Bras Basah Road and Bukit Timah, women who chose to wear cheongsams were offered top-class workmanship as well as a wide range of fabrics in cheongsam tailoring. There were also smaller tailor shops that catered to women with more modest means.

Johnny Chia, in his 60s, a former singer at the Happy World Cabaret whom I interviewed, recalled the cabaret women he had known and respected: “They were so beautiful in their cheongsams! Many of them were natural beauties with very little makeup. They loved music and they loved dancing. It doesn’t matter what I was singing, whether it was Western, Cantonese or Baba Malay songs, they would know the steps.”

In the 1950s, when Singapore was a regional distribution centre for textiles because of its entrepôt trade and free port status, women were able to buy the trendiest fabrics for their cheongsams, which were also made affordable with the introduction of synthetic textiles. Artificial fabrics were popular because they were easy to wear and maintain. Durable, lightweight and not easily creased, they made cheongsam-wearing hassle-free for the working cabaret girl.36

By the 1960s, there emerged the concept of a “national dress” that appeared on fashion models in advertisements. In Malaysia, women were encouraged to wear the modern sarong kebaya, often together with other models in cheongsam and sari, as an expression of multiracial harmony. Chinese women would wear the cheongsam, and Indian women would wear the sari. Fashionable pairings, such as wearing a sarong and kebaya made of the same batik fabric, emerged around this period and inspired the uniform for Malaysia-Singapore Airlines. Batik was also adapted for swimwear, westernstyle dresses, and of course, the ubiquitous cheongsam.37

Fashion aside, Singapore’s music scene, too, could claim to have been influenced by the cabarets. From the 1920s to the 1940s, music in churches and at the cinemas provided artistic enjoyment, but the venues of Singapore’s mass entertainment facilities, the dance halls, also provided a platform for the growth of music appreciation. The cabarets played a special role in hosting foreign bands set up along the lines of the European big bands. The audiences were able to listen to a properly constituted dance orchestra. Comprising three sections, with saxophones, trumpets and trombones, and rhythm provided by the pianos, drums, guitars and double bass, cabaret dance orchestras were no different from European or American swing bands, which were then all the rage. Popular music from the films of those days was standard fare for the bands and they made up “combos” of various descriptions.

The three entertainment Worlds, with their multifarious attractions, restaurants, jugglers, magicians, wayang and sporting events, were ideal places for family outings. The dance halls, with their soothing sounds of mellifluous saxes, complemented by the steady rhythms of a slow foxtrot or waltz, could have been the scenes of seduction where many men fell in love with dance music and the cabaret girls.38

Bunga Tanjong and the Perempuan Joget

When examining the influences of the cabaret, I came across a play that was inspired by a well-known cabaret in the Malay-speaking world. Originally titled Lantai T. Pinkie, the play was written by A. Samad Said, a Malaysian playwright and author. The Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia Berhad republished the play as a book in 2010, with permission from Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Malaysia, using their translated work published in 2003.

T. Pinkie’s Floor was first performed by Teater Kami from 5 to 6 June 1996 at the World Trade Centre Auditorium, Singapore, as part of the Singapore Arts Festival.

A. Samad Said revealed in an interview that he had written the play based on his memories of the early 1950s and 1960s, when he used to frequent New World. He identified himself as one of the gangsters who kept watch over his “base” around Maude, Syed Alwi, Owen, Kerbau and Hindoo roads, noting that the area was “a busy world unto itself with hotels and the entertainment district, and there were gangsters all over!”39

This is the missing element in descriptions of the cabaret world: one of danger, where secret societies cast their long shadows over the cabaret girls. In the words of A. Samad Said, gang members “struck terror and [were] greatly feared”.

The cabaret referred to in the area was none other than Bunga Tanjong. A gang that was mentioned was the “Gang Jambatan Merah” (Red Bridge Gang), which operated around the Newton area. A. Samad Said worked for this gang and was tasked to collect “protection money” from the joget dancers under his watch. He described this world as one where “there were always fights, between gangs, between the police and the army”. A. Samad Said also added that “if a fight broke out, the police would arrive in their lorry”.40

A. Samad Said described writing T. Pinkie’s Floor as a “document of an era, a decade, a way of life that when it’s no longer there, it becomes important. You take all those stories, they all happened around me, and they become a documentary about an era”.41

The play traces a series of flashbacks unveiled by former accordion player Muhairi Tirus to a young man named Loiran Sindu, who was piecing together the story of a lost world that his mother had shared before she died. This lost world comprised the lives of several perempuan joget(female dancers) of a “dance floor” (hence the title of the play). T. Pinkie was later revealed to be Loiran’s grandmother, told through a sad account of how she had been raped and held captive by a gangster head.

In a wistful sharing of how A. Samad Said arrived at the name of “Pinkie” for the protagonist, he described her as the “most beautiful woman” in the joget world. “Her beauty is represented by her pink baju (blouse). Pinkie epitomises all the desires, the impossibilities, the love and the brawls of men who want her. Men went to the* joget* world to possess her. If they could, they would buy 12 or 20 tickets and they would want to give all of them to Pinkie so that they would be the only one to dance the night away with her. They would want to have sole monopoly over Pinkie and this was the source of all the fights and brawls. Pinkie of New World was an amalgamation of many beautiful women of the joget world.”.42

The “Singaporeanness” of the Cabaret

In 1988, as part of the Singapore Arts Festival, four young men got together for the first time to write, produce, cast and direct Singapore’s first English musical, Beauty World. Writer Michael Chiang, 33, songwriter Dick Lee, 31, choreographer Mohd Najip Ali, 23, and director Ong Keng Sen, 24, would later go on to headline the local creative arts scene for several decades. The cast also featured a stellar line-up of actors, with Claire Wong, Ivan Heng and Jacinta Abisheganaden, who would all become familiar names in Singapore’s playwriting and acting community.

Set in the 1960s, the story is about a small-town Malaysian girl from Batu Pahat, Ivy Chan Poh Choo, who travels to Singapore to uncover the mystery of her parentage. Her only clue to finding her father is a jade locket inscribed with the words “Beauty World”, which leads her to join the seedy cabaret where most of the action unfolds. Within the complex world of caterwauling cabaret girls and lecherous men, Ivy has to keep her head above water and still remain true to her boyfriend, Frankie.

The inspiration for the musical was drawn from the cabaret world of the 1960s, replete with music and lyrics reminiscent of the cha-cha-cha dance era. In the style of Broadway, Beauty World’s tunes were catchy, although some criticised that the songwriter had written 1980s contemporary pop music for a 1960s world.43

When asked why the story was set in a cabaret, Chiang shared that it was “something nostalgic that was also unique to Singapore”. In a commentary made in Private Parts & Other Play Things: A Collection of Popular Singapore Comedies by Michael Chiang, Ong Keng Sen said that “the performance of Michael’s plays are charged with a raw community energy and pride which reverberates in the theatre. His work crosses language and racial boundaries by celebrating our ‘Singaporeanness’ rather than by dividing us”.44

Echoing the sentiments of this statement, I would say how true it is that the cabaret is a celebration of a slice of our unique history; its indelible “Singaporeanness” is affirmed by the attitudes of the people I interviewed for this paper. Every one of them spoke of the past with whimsical longing, and even if their lives had been scarred by pain and struggle, they shared their stories with the quiet pride of having experienced life in the cabaret.

For Wong Siew Wah, Ong Swee Neo, Edward Khoo and Johnny Chia, I have no doubt that if any of them were given a chance to relive their pasts all over again, they would not change a single thing.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdul Samad Said. T. Pinkie’s Floor: A Nostalgic Play. Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia, 2010). (Call no. RSEA 899. 282 ABD)

Abisheganaden, Paul. Notes Across the Years: Anecdotes From a Musical Life. Singapore: Unipress, 2005. (Call no. RSING 780.95957)

Anonymous 2, oral history interview by Daniel Chew, 27 February 1985, MP3 audio, Reels/Discs 1–4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000529)

Interview with Edward Khoo on 30 May 2016.

Interview with Ong Swee Neo on 24 February 2016.

Interview with Wong Siew Wah on 11 February 2016.

Kua, Kia Soong. The Chinese Schools of Malaysia: A Protean Saga. Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: Malaysian Centre for Ethnic Centre, New Era College, 2008, 31, 34. (Call no. RSEA 371.009595 KUA)

Lee, Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen. In the Mood for Cheongsam. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore, 2012, 28. (Call no. RSING 391.00951 LEE-[CUS])

Lee, Peter. Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World, 1500–1950. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2014, 286–87. (Call no. RSING 391.20899510595 LEE-[CUS])

“Musical Practices of Jazz,” in Eugene I. Dairianathan, A Narrative History of Music in Singapore 1819 to the Present (From National Library Online)

Nanyang Siang Pau. “Wunu de xinli xue” 舞女的心理学 [The psychology of dancing girls]. 1 February 1937, 24. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wunu shenghuo ku huan chang re bing” 舞女生活苦患肠热病 [Dancing girl suffers from enteric fever]. 1 July 1938, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wu guo de yi duo qing lian heyanna” 舞国的一朵青春何燕娜 [He Yanna, a green lotus in the dancing country]. 25 January 1947, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Kuai yue xuexiao cishan wu hou xuqianhong fangwen ji” 快乐学校慈善舞后许千红访问记 [Interview with Happy School Charity Dance Queen Xu Qianhong]. 10 June 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wunu xuqianhong goumai nu an panjue beigao qian bao wubai yuan zai yi niannei bude zaifan” 舞女许千红购买女案判决被告签保五百元在一年内不得再犯 [In the case of dancing girl Xu Qianhong purchasing a girl, the defendant was sentenced to a five-hundred-yuan bond and must not commit the crime again within one year]. 14 March 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wunu de shenghuo” 舞女的生活 [Dancer’s life]. 30 November 1976, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

National Library Board. The Three Worlds (大世界、新世界、繁__华世界) : Great, New and Happy, 2012. (From National Library Online)

New Nation. Yeo, Toon Joo et al., “Glamour Only a Façade.” 5 October 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG)

Ong, Christopher. Rose Chan. Singapore Infopedia, published May 2021.

Singapore Free Press. “Pay Talks: Clerks Not Satisfied.” 23 August 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Income Tax Deduction for Glamour.” 20 January 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Club Aids Cabaret Girls.” 27 August 1953, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

Singapore Free Press & Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942). “Cabaret Girls’ Association.” 7 November 1939, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

Straits Times. “Amusements: Happy World.” 17 November 1939, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Singapore Needs More Schools.” 23 November 1947, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Cabaret Girls Help in Registration.” 30 October 1948, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Kindest Cut by Women Barbers.” 23 October 1949, 9. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Hwang, T. F. and Dorothy Thatcher. “Nancy and Judy, Two Women With Courage.” 24 August 1952, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Victim of an Abortionist Takes Secret to the Grave.” 3 November 1962, 11. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Bar Girl Tells of an Abortionist, Then Dies.” 21 December 1962, 13. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Yeo, Robert. “Something To Celebrate a Landmark Musical.” 3 July 1988, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Foo, Adeline. “The ‘Lancing’ Girls From a Glitzy World.” 30 April 2016, 45. (From NewspaperSG)

Ong, K. S. “Introduction.” In Michael Chiang. Private Parts and Other Play Things: A Collection of Popular Singapore Comedies. Singapore: Landmark Books, 1993. (From PublicationSG)

Pan, Xinghua 潘星华, ed., Xiaoshi de hua xiao: Guojia yongyuan de zichan 消失的华校: 国家永远的资产 [Disappeared Chinese schools: a permanent asset to the country]. 新加坡: 华校校友会联合会出版, 2014. (Call no. Chinese RSING 371.82995105957 XSD)

Wang Zhenchun 王振. Gen de xilie 根的系列 [Root series]. 新加坡: 胜友书局, 1988, 153. (From PublicationSG)

NOTES

-

Adeline Foo, “The ‘Lancing’ Girls From a Glitzy World,” Straits Times, 30 April 2016, 45. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board, The Three Worlds (大世界、新世界、繁__华世界) : Great, New and Happy, 2012. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

“Amusements: Happy World,” Straits Times, 17 November 1939, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Musical Practices of Jazz,” in Eugene I. Dairianathan, A Narrative History of Music in Singapore 1819 to the Present (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Interview with Ong Swee Neo on 24 February 2016. ↩

-

Interview with Wong Siew Wah on 11 February 2016. ↩

-

“Pay Talks: Clerks Not Satisfied,” Singapore Free Press, 23 August 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cabaret Girls’ Association,” Singapore Free Press & Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 7 November 1939, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Income Tax Deduction for Glamour,” Singapore Free Press, 20 January 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T. F. Hwang and Dorothy Thatcher, “Nancy and Judy, Two Women With Courage,” Straits Times, 24 August 1952, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Christopher Ong, Rose Chan, Singapore Infopedia, published May 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Edward Khoo on 30 May 2016. ↩

-

“Club Aids Cabaret Girls,” Singapore Free Press, 27 August 1953, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wang Zhenchun 王振春, Gen de xilie 根的系列 [Root series] (新加坡: 胜友书局, 1988), 153. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Wang, Gen de xilie, 153. ↩

-

“Wu guo de yi duo qing lian heyanna” 舞国的一朵青春何燕娜 [He Yanna, a green lotus in the dancing country], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 25 January 1947, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Kuai yue xuexiao cishan wu hou xuqianhong fangwen ji” 快乐学校慈善舞后许千红访问记 [Interview with Happy School Charity Dance Queen Xu Qianhong], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 10 June 1947, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Needs More Schools,” Straits Times, 23 November 1947, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kua Kia Soong, The Chinese Schools of Malaysia: A Protean Saga (Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: Malaysian Centre for Ethnic Centre, New Era College, 2008), 31, 34. (Call no. RSEA 371.009595 KUA) ↩

-

Pan Xinghua 潘星华, ed., Xiaoshi de hua xiao: Guojia yongyuan de zichan 消失的华校: 国家永远的资产 [Disappeared Chinese schools: a permanent asset to the country] (新加坡: 华校校友会联合会出版, 2014), 140–41. (Call no. Chinese RSING 371.82995105957 XSD) ↩

-

“Wunu xuqianhong goumai nu an panjue beigao qian bao wubai yuan zai yi niannei bude zaifan” 舞女许千红购买女案判决被告签保五百元在一年内不得再犯 [In the case of dancing girl Xu Qianhong purchasing a girl, the defendant was sentenced to a five-hundred-yuan bond and must not commit the crime again within one year], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 14 March 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wang, Gen de xilie, 149. ↩

-

Wang, Gen de xilie, 149. ↩

-

“Wunu de xinli xue” 舞女的心理学 [The psychology of dancing girls], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 1 February 1937, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wunu shenghuo ku huan chang re bing” 舞女生活苦患肠热病 [Dancing girl suffers from enteric fever], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 1 July 1938, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wunu de shenghuo” 舞女的生活 [Dancer’s life], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 30 November 1976, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cabaret Girls Help in Registration,” Straits Times, 30 October 1948, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Kindest Cut by Women Barbers,” Straits Times, 23 October 1949, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Anonymous 2, oral history interview by Daniel Chew, 27 February 1985, MP3 audio, Reels/Discs 1–4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000529) ↩

-

“Victim of an Abortionist Takes Secret to the Grave,” Straits Times, 3 November 1962, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bar Girl Tells of an Abortionist, Then Dies,” Straits Times, 21 December 1962, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeo Toon Joo et al., “Glamour Only a Façade,” New Nation, 5 October 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen, In the Mood for Cheongsam (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: National Museum of Singapore, 2012), 28. (Call no. RSING 391.00951 LEE-[CUS]) ↩

-

Peter Lee, Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World, 1500–1950 (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2014), 286–87. (Call no. RSING 391.20899510595 LEE-[CUS]) ↩

-

Lee and Chung, In the Mood for Cheongsam, 53. ↩

-

Lee, Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World, 1500–1950, 285. ↩

-

Paul Abisheganaden, Notes Across the Years: Anecdotes From a Musical Life (Singapore: Unipress, 2005), 9. (Call no. RSING 780.95957 AB) ↩

-

Abdul Samad Said, T. Pinkie’s Floor: A Nostalgic Play (Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia, 2010), 120–21. (Call no. RSEA 899. 282 ABD) ↩

-

Abdul Samad Said, T. Pinkie’s Floor: A Nostalgic Play, 120–22. ↩

-

Abdul Samad Said, T. Pinkie’s Floor: A Nostalgic Play, 123. ↩

-

Abdul Samad Said, T. Pinkie’s Floor: A Nostalgic Play, 124–25. ↩

-

Robert Yeo, “Something To Celebrate a Landmark Musical,” Straits Times, 3 July 1988, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ong K. S., “Introduction,” in Michael Chiang, Private Parts and Other Play Things: A Collection of Popular Singapore Comedies (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1993), 8. (From PublicationSG) ↩