Searching For The “Real” Singapore In Hollywood Feature Films

By Chua Ai Lin

Introduction

In January 1936, an article in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser remarked that with so many American filmmakers arriving on local shores, “Singapore is becoming the equatorial Hollywood”.1 Two months later, an editorial in the same newspaper entitled “The Film Invasion” described the “invasion of film people from Hollywood” including “such famous names as Frank Buck, Ward Wing, Tay Garnett, James A. Fitzpatrick, and Percy Marmont, to say nothing of Charlie Chaplin”.2 It should be no surprise that the American film industry had such a strong impression of Singapore, which, as a major port in the British Empire, had gained a reputation for being the “Charing Cross of the East” and “Clapham Junction of the East” since the 1880s.3

With motion pictures at the turn of the century showing scenes of a modern, Asian port city inhabited by an exotic mix of cultures, Singapore entered Hollywood’s imaginative vocabulary of exotic locations. The earliest footages would have been newsreels, documentaries and travelogues. Twenty-four such films from 1900 to 1919 and nine from 1920 to 1928 have been identified, most notably works by leading international newsreel production company, Pathé, as well as four 1913 films by Gaston Méliès, brother of renowned French filmmaker Georges Méliès, which were screened in American cinemas that year.4

This paper looks at Singapore in the Hollywood imagination and how this was expressed in non-travelogue feature films from the late 1920s to 1940, and in particular how “real” the Singapore depicted in these films was. These productions ranged from ones where Singapore was a vague setting in the exotic East, with no actual footage of Singapore, to films that attempted varying degrees of realism through location shoots, local actors and extras, or depictions of Malayan life. One protagonist emerges from this history of Hollywood in Singapore – director Clyde Ernest Elliot, who had come to Singapore repeatedly, releasing first a short travelogue as part of the Post Travel Series in 1918, and then three feature films – Bring ’Em Back Alive (1932), Devil Tiger (1934) and Booloo (1938) – each time attempting to depict Malaya more realistically within the expectations and limitations of the Hollywood studio system.

Fictional Singapore

While reportage and travel films featuring Singapore were made from the turn of the century, it was only from 1928 that fiction films set in Singapore began to be produced. The period from 1928 to 1933 saw several of these: Across to Singapore (1928), Sal of Singapore (1928), The Crimson City (1928; Italian title: La schiava di Singapore), The Letter (1928), The Road to Singapore (1931), Rich and Strange (1931), Out of Singapore (1932), Malay Nights (also titled as: Shadows of Singapore, 1932), Singapore Sue (1932) and West of Singapore (1933).5 None of these films were shot near the tropics and only one, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rich and Strange, included authentic scenes of Singapore – albeit only from stock footage.6

Several of these were adaptations from other mediums. Across to Singapore was based on the 1919 novel All the Brothers Were Valiant by Ben Ames Williams, while works by Australian author Dale Collins inspired two film adaptations – Sal of Singapore (based on the novel The Sentimentalists) and Rich and Strange (based on a book of the same name).7 The Road to Singapore was adapted from a 1929 British stage play, Heatwave, by Mills & Boon writer Denise Robins and playwright Roland Pertwee, while The Letter had a more respectable literary pedigree as the dramatisation of a Somerset Maugham short story of the same title.8

Of these works, those by Dale Collins and Somerset Maugham were based on personal observations by the authors. Both made numerous trips around the world to gather ideas for their writings and both passed through Singapore in the early 1920s.9 Each chose settings and storylines that echoed their own experiences. The Sentimentalists was set on a long sea journey that paralleled Collins’ journey round the world in a yacht owned by American millionaire A.Y. Gowen, reporting on their travels for The Herald (of Melbourne, Australia).10 Rather than focus on the liminal experience in between ports of call, Maugham spent months at a time in specific regions so as to understand those societies in greater depth.11 The Letter was based on the sensational real-life murder of William Steward, a mine manager, by Mrs Ethel Proudlock, a Eurasian woman married to an English headmaster of the prestigious Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur.12

In contrast, Across to Singapore and The Road to Singapore were based on a fictional setting, whereby Singapore was used in symbolic terms to evoke certain characteristics of an exotic seaport. All the Brothers Were Valiant, the novel that Across to Singapore was based on, was originally set in the Gilbert Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Like The Road to Singapore, the story was primarily set on a ship in the Pacific, with Singapore appearing only briefly as a port of call.13 Nevertheless, these romanticised renderings presented an image of Singapore generally similar to that unveiled by films based on first-hand research. All the off-location films shot between 1928 and 1933 fell into one of two categories: the seafaring tale (Across to Singapore, Sal of Singapore, Out of Singapore and Singapore Sue), or the sultry and often illicit love affair set in colonial society (The Letter, Rich and Strange, Malay Nights and West of Singapore).

The Road to Singapore combined both these elements. Singapore acted as a literary shorthand for a port in the exotic tropics, where passions ran as hot as the climate. These stories were an extension of a long-standing trope. Scientific thinking in the 19th century blamed the tropical climate for all manner of physical and behavioural ills, giving rise to the literary stereotype of flirtatious girls and adulterous wives in the British Raj. Gossip newspapers such as The Civil and Military Gazette and the stories of Rudyard Kipling popularised the dramatic potential of such tales, which were reproduced in a new setting and medium within these early movies set in Singapore.14

Jungle Documentaries

The first on-location foreign film made in Singapore emerged from a very different source of inspiration and was neither set at sea nor about a passionate romance. Building on the established practice of newsreel filming, Bring ’Em Back Alive was a documentary feature based on the adventures of Frank Howard Buck, a Texan wildlife collector who had established his base in Singapore since World War I. The book of the same title by Buck, already known as a major animal supplier to zoos in America, became a bestseller in the US when it was released in 1930.15 Backed by Van Beuren Studios, produced by Buck and director Clyde Elliot, and distributed by RKO Pictures, the strong reception of the book paved the way for its cinematic success. Box office takings hit a million dollars within eight months of its release and the film was one of RKO ’s most profitable releases in 1932.16 Following its release, Buck travelled to London and the US , giving speeches to coincide with screenings.17

Ostensibly a documentary, Bring ’Em Back Alive was heavily criticised by audiences in the know, with American naturalist Harry McGuire caustically calling Buck’s film a “hocus pocus” work of “nature faking” and The Straits Times’ correspondent going “hot under the collar” at the string of inaccuracies in the film.18 Buck bore the brunt of the bad press but pointed the finger of blame at Elliott instead. Elliott had readily admitted in public that scenes of a tiger being shot dead and a python fighting a crocodile had been staged for the camera.19 Buck said, “To my mind he has been very silly and rather ridiculous. All pictures are made to entertain people and if a fellow stands up and deliberately spoils the illusion he is biting the hand that feeds him…. I don’t mean we want to fool people – as a matter of fact the picture was made under more natural circumstances than any other of its kind.”20

Such controversies were nothing new in the context of the times. Java expert Huber S. Banner commented, “The trouble is, though, that after seeing one of these jungle films that are all the rage nowadays – Frank Buck’s epic of the Malayan forests, Bring ’Em Back Alive’, for instance – nobody will believe that one doesn’t go about in constant peril.”21 Bring ’Em Back Alive’ was quite likely one of the more realistic films of the genre, as Buck asserted, going by the detailed description in “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger- Python Battle”, an article from the American periodical Modern Mechanix and Inventions. When interviewed, Buck and the main cameraman, Nick Cavaliere, explained how they capitalised on normal patterns of animal behaviour around a watering hole by steering a tiger into a forced encounter with a python.22

Yet there were many different levels of artifice involved in making Bring ’Em Back Alive; the realism of animal behaviour was only one aspect. The other was the locations where these scenes were shot. Viewers were led to believe that they were watching action from the heart of the Malayan jungle when, in fact, the close-up scenes were shot at Jurong Road just a few miles away from downtown Singapore.23 By providing a tropical location for filming, Singapore was an essential component in creating the illusion of realism that caught the attention of international audiences. Buck’s emphasis on a successful “illusion” and that “all pictures are made to entertain” made it clear that this form of filmmaking was of a different spirit from the newsreels and documentary films of an earlier era, which news agencies had continued to shoot.

The criticisms of Bring ’Em Back Alive did not hold the Texan adventurer back from international fame and Buck churned out a constant succession of books and films in a similar vein: Wild Cargo (book, 1932; film, 1934), Fang and Claw (book and film, 1935), On Jungle Trails (book, 1936), Jungle Menace (a 15-part film serial, 1937), Animals Are Like That (book, 1939), Jungle Cavalcade (film compilation of footage from his first three films, 1941), All in a Lifetime (autobiography, 1941), Jacaré (film, 1942), Tiger Fangs (film, 1943) and Jungle Animals (book, 1945).24

Buck’s success was due partly to his larger-than-life persona but also to the prolific stream of works that kept him in the spotlight. A strategic interfacing of his stories in different forms exposed his works to different audiences and reinforced their impact. For example, in 1930, the book Bring ’Em Back Alive became an international bestseller – appealing to audiences in both Buck’s own America, as well as to the British public, who were intrigued by the Malayan aspect of the empire. Two years later, the stories from Bring ’Em Back Alive were brought to life via moving pictures and the following year, in 1933, Buck set up a wild animal camp at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago, which was visited by two million visitors in the two years of its existence. In 1939, Buck brought the same camp exhibit, with thousands of wild animals, to the New York World’s Fair.25

In this respect, Buck’s work made a far greater impact than that of his contemporary, Ernest B. Schoedsack, a director of travelogues on Persia and Siam who had travelled to Sumatra to make the orang-utan film, Rango (1931). Despite the fact that Elliot had noted that Rango was more authentic than Bring ’Em Back Alive, and that it was regarded by cinema historian Derek Bouse as possibly the “first fully-realised wildlife film, in the modern sense”, it failed to achieve box office success.26 Bring ’Em Back Alive brought fame not only to Buck, but also thrust Malaya into the consciousness of international audiences, with many cinemas even displaying maps. “At last, many people realised that Singapore is not in South Africa or China, or anywhere but where it is,” declared Elliott.27

Ethnographic Fiction Films

Inspired by the success of Bring ’Em Back Alive and the cinematic potential of Malaya, Elliott was back in Singapore by November 1932, with a Hollywood crew and a cast led by rising star Marion Burns, to film Man- Eater, “the first talkie made entirely in the jungle” for Fox Film Corporation (released in 1934 as Devil Tiger). While Bring ’Em Back Alive was “a purely animal story”, Man-Eater moved one step further from documentary films with its dramatised storyline.28 However, Man-Eater was not the first American feature drama to go on location in Malaya. Barely a month earlier, an American crew under the direction of Ward Wing and funded by the independent B.F. Zeidman Productions, with a script by the director’s wife Lori Bara, had started filming Samarang, a “simple native romance”, set in a pearl-diving community in Singapore.29 These movies were part of a trend of “natural dramas” beginning in the late 1920s, which were scripted, fictional films shot in exotic locations with a cast of local actors.30 Elliott’s progression from animal behaviour to human drama was mirrored by the career of Ernest Schoedsack, whose biography and documentary film Rango provided inspiration for the iconic movie King Kong, which was written by Schoedsack’s long-time collaborator and friend, Merian Cooper.31

Moving away from a jungle setting, Samarang was shot on location along the coasts and offshore islands near Singapore.32 The cast were all local amateurs. Playing the female lead, “Sai-Yu, beautiful daughter of the tribal chieftain” was Therese Seth, an amateur dancer of Armenian ancestry who was talent-spotted by the film’s producers when she performed at the Capitol Follies.33 The male protagonist, a pearl diver named Ahmang, was played by an Englishman, Captain Albert Victor Cockle, who was Chief Inspector of Police as well as an amateur actor.34 His “exceptionally fine physique” earned him the “reputation of being the ‘new Tarzan’” and direct comparisons with Tarzan star Johnny Weissmuller.35 The director, Ward Wing, went to great lengths to make the movie convincing. Screen tests were held and several bangsawan actors auditioned.36 To play the “natives” he took the trouble of engaging extras from the Sakai tribe, who were “reputed to be cannibals”, in spite of the difficulties involved:

Only one man could be found who could speak the Sakai language,

but he was Chinese and knew no English, so a Malay who spoke

Chinese was found, but he, in turn, could not speak English,

so Wing had to tell an English-speaking Malay what he wanted.

The Malay would tell the Malay speaking Chinese, who would

tell the Chinaman, who would tell the Sakai!

This lengthy procedure had its difficulties for, by the time so many

people had translated Wing’s directions, they were sometimes

entirely different.37

Even Captain Cockle had to assist the director in translating instructions into Malay, and additional Tamil interpreters were also hired for Indian supporting cast members.38 No effort was spared in maximising the dramatic potential of the natural surroundings as well. The underwater scenes of a real-life fight between a tiger shark and octopus, shot by cinematographer Stacy Woodward, were considered of important documentary value and caught the attention of American “biological experts” such as Dr Hazel Branch of Wichita University.39 A New York Times review of the film expressed that it “is a picture distinguished by the obvious authenticity of many of its scenes. The flashes of the divers are shrewdly pictured – first by the men plunging into the sea and later by revealing them below, picking up shells. It is, of course, a fiction story, to which a certain realism is lent by the portrayals by the natives”.40

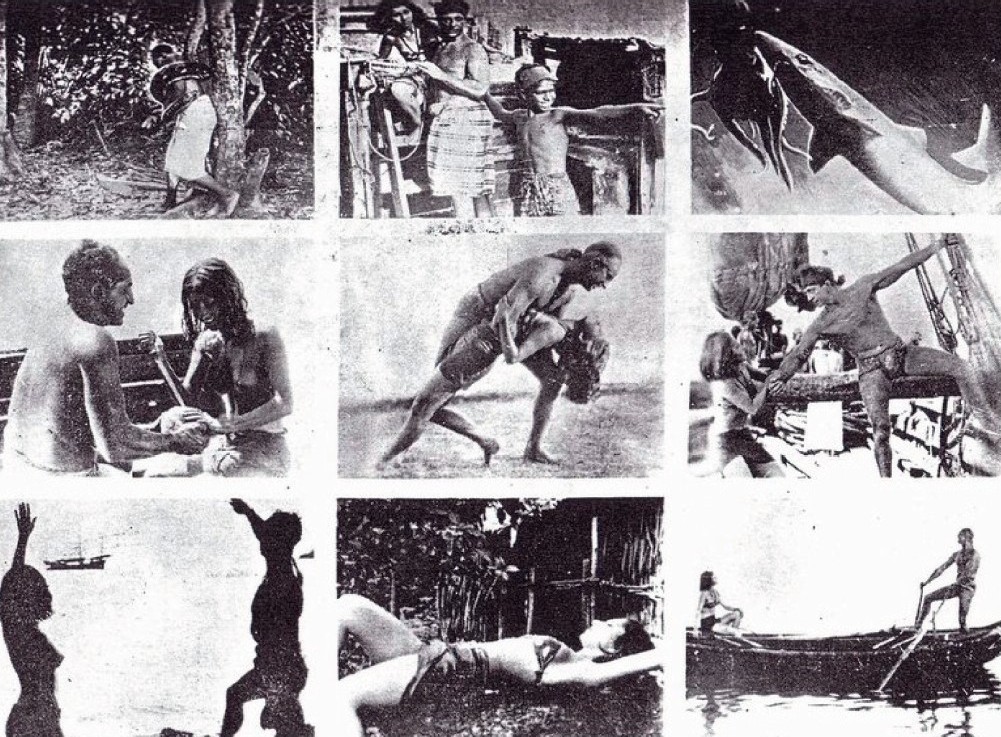

Th e ethnographic tone of parts of the fi lm, particularly the introductory section filmed in a malay kampong (village), provided a veneer of respectability for the unabashedly risqué scenes featuring Cockle and seth. Th ey were clothed in the skimpiest of loincloths and a bikini top, and fl irted suggestively with each other. seth also appeared topless for most of the 58 minutes of the fi lm (Fig. 1).41 The film inspired a mini-revolution of public exposure of the human body in america. For its opening in new york, the samarang Club was inaugurated, “which provided that all its members should wear bathing shorts and not the complete costume”.42 at Californian seaside resorts, men flouted local laws and went swimming with bare chests causing “large batches of swimmers [to] have found themselves before the local magistrate”. As members of clubs were exempt from such laws, many joined the Samarang Club.43

Passing for a quasi-documentary on natives of the South Seas, Samarang could depict the nude female body in a way that mainstream films set in western society could not. The Pacific Islands and Bali, in particular, were popular locations for similar “nature dramas” that capitalised on the sexual potential of native scenes in exotic locations. F.W. Murnau’s sexually-charged Tabu (1931), filmed in Bora Bora with amateur actors and a local cast, was the most successful of these; but there were others, such as Balinese Love (1931), Goona Goona (1932, also known as Kriss), Isle of Paradise (1932), Virgins of Bali(Land of Love and Romance) (1932), Wajan (1933) and Legong: Dance of the Virgins (1935).44

In the words of film studies scholar Peter Bloom, this “was an auspicious genre of documentary filmmaking because it supported the fantasy and mythology that accompanied the first wave of the far-flung mass international tourist trade”.45 The term “goona-goona” became Hollywood industry slang for shots of bare-breasted non-white women.46 On-location filming and the use of a local amateur cast, even if the action was fictional rather than ethnographic documentation, was likely to have been the key to sneaking salacious content past conservative forces in Hollywood and the American public under the veneer of realism. Following Tabu’s positive reception, it was remade by RKO as a studio film called Bird of Paradise (1932), directed by Oscar-winning director King Vidor with a professional cast. But the topless shots and nude swimming scene were found objectionable under the strict moral standards of the Hays Production Code, curtailing the film’s circulation and resulting in – despite the reputation of Vidor and renowned producer David O. Selznick – a loss of US $250,000 at the box office.47

As a silent film by an independent production company, Samarang was quite different in scale from Devil Tiger. The latter was funded by a major studio, featured a well-known Hollywood cast and, most importantly, was the first talkie entirely produced in Malaya and Singapore.48 Elliott arrived in Singapore with eight tonnes of equipment, a cameraman, sound engineers, “three rising stars in Hollywood” – Marion Burns, Kane Richmond and Harry Woods – as well as a New York Times reporter. After his fallout with Buck, Elliott turned to a local Eurasian zoological collector, Herbert de Souza, for professional advice on the animal scenes.49

Devil Tiger was tame in comparison to the challenges Samarang had faced working with a native cast and public attention arising from its daring nudity. Locals – many were Caucasian residents in Singapore – were cast as extras in genteel hotel party scenes.50 Mishaps that occurred during production were kept under wraps for fear of bad publicity, but after the movie’s release, it was revealed that cameraman Jack Dunn had been “mauled by a black panther” and “Kane Richmond had two ribs fractured by a constricting python”.51 While American film reviewers described Devil Tiger as “thrilling”, “realistic” and “informative”, and one of Fox Films’ best films of 1934, local audiences found it forgettable and were nonplussed by the exaggerated portrayal of the Malayan jungle.52

Perceptions of realism and authenticity, and the value attached to these qualities, were at odds with the film’s shooting location and its target market on the other side of the globe.

Other filmmakers also expressed a desire for the kind of approach used in Devil Tiger. In March 1936, the well-known travelogue producer James A. Fitzpatrick was in Singapore to collect scenes and background for two films. In an interview he said that he hoped to return to make a feature film: “It will have a plot drawn from the life of this unique city of the East. My stars I will bring with me. There will be no superimposing of plot or players against a pre-photographed Singapore background.” He also criticised the “over-coloured imaginations of ‘hokum’ writers who spend a few days here, then go back to the States and write of the gin-sling and champagne imbibing ‘beachcombers’ and such characters dear to the penny novelettes”.53

Realistic Fiction Over Dramatised Realism

Devil Tiger, however, failed to make its mark at the box office. That honour went to The Jungle Princess (1936), a Paramount Pictures film written and directed by William Thiele, which became the most successful film set in Malaya since Bring ’Em Back Alive.54 The film launched the career of Dorothy Lamour, who became known for her sarong costumes in many films, an image created by her role as a native girl in The Jungle Princess. Although filmed in Hawaii, this was the first talkie film to use actual Malay dialogue. The story reflected a multi-ethnic Malayan society by including a Chinese servant alongside the Malay villagers and European hunters.55 Ray Milland acted as a British explorer rescued in the jungle by a native girl (Dorothy Lamour) who had grown up in the jungle with only a pet tiger and pet chimpanzee for company. Tightly directed and combining drama, comedy, romance and jungle action with captivating singing from Lamour, the film played to full houses in Singapore and, unlike all the other previous Malayan films, received the Singapore critics’ thumbs up.56 The Jungle Princess even inspired a remake entitled Terang Boelan (1937), which was the first Indonesian film in Malay, scripted by Indonesian journalist Saeroen, with cinematography by David Wong, an Indonesian-Chinese.57

Just months after the well-received release of The Jungle Princess, Paramount Pictures set out to go one step further with a similar Malayan jungle romance-adventure filmed on location in the tropics. The director of Booloo was Elliott, who had established his Malayan credentials with Bring ’Em Back Alive and Devil Tiger.58 With 10 tonnes of “the most up-to-date, portable, light and sound equipment”, Elliott had even better resources to work with on Booloo compared to his previous Malayan films.59 The story behind Booloo expresses most clearly the tension between realism and staged fiction. Although Elliott had been criticised for taking creative licence in both Bring ’Em Back Alive and Devil Tiger, he struggled against the commercial impositions by Paramount Studios in Hollywood to preserve authenticity in Booloo.

Like Samarang, Booloo intended to feature local amateur actors from Malaya cast alongside Paramount actor Colin Tapely.60 After an exhaustive search where “girls from practically every class of Singapore society from Tanglin to Chinatown [were] given film tests”, a Javanese dancer named Ratna Asmara, from the Dardenalla travelling performance troupe, was cast in the lead role of a Malay girl. Playing her Malay lover was Singaporean-Eurasian Fred Pullen.61 Supporting roles were assigned to locals Elliott was familiar with from Devil Tiger – the wildlife collector Herbert de Souza, Ah Ho (a Chinese male) and Ah Lee (a young boy of not more than 10 years old), who had played a minor role; as well as Europeans based in Singapore, such as professional actor Carl Lawson, and two army officers.62

With the casting of Ratna Asmara, it would seem that Booloo did what both Samarang and The Jungle Princess could not – a Malay protagonist played by a local actress speaking in her natural vernacular. However, this was perhaps simply too real for American audiences and, to Elliott’s dismay, most of his location shoots with the Malayan cast were left on the cutting room floor.63 Paramount decided to reshoot most of the film in Hollywood and Ratna Asmara was replaced by Mamo Clark, famed for Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), where she had starred alongside Clark Gable.64

If Dorothy Lamour had been convincing enough as a native Malay girl, then casting a genuine native girl was less important than Clark’s celebrity status. While The Jungle Princess was enhanced with a dose of realistic elements, Booloo’s attempt at realism seemed to have crossed a line. It never achieved the success of The Jungle Princess, instead receiving scathing reviews that panned the “silly story” and the “jungle and Hollywood sequences [which had] been spliced together so crudely”.65 Not even the Caucasianlooking Pullen, acting as a Malay boy, passed muster, and only one of his scenes was retained. Pullen was “extremely disappointed” and wrote to the producers to complain.66 Booloo was the last of the pre-war, location feature films that received an international commercial release.

Two other efforts around this time deserve mention, as well as to provide a contrast with Elliot’s attempt at realism in Booloo. Tay Garnett, a freelance director for leading studios Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer, Columbia and Twentieth Century, arrived to much fanfare in February 1936, taking the unusual step of spending two weeks in Singapore to capture authentic footage of “[the] Singapore harbour and shipping, of streets and buildings, Chinatown, cabarets and night-life, Malay kampongs, jungles, rubber plantations, fauna and other features of Malaya”.

The footage was to be used back in Hollywood as a backdrop for the cast to act in front of “so that they [would] have a genuine Malayan background instead of a fake one”.67 Garnett wanted to avoid the pitfalls of other motion pictures, which “did not always depict Eastern scenes and atmosphere faithfully”, particularly by showing “advanced Asiatic races as barbarians”. He planned for two films to be made with his location footage: Trade Winds, which was released in 1938, and Singapore Bound, which was ultimately never made. The former was a detective romantic comedy starring Joan Bennett and Fredric March, which was, in addition to Singapore, also set in Japan, Shanghai, Colombo and Bombay.68 Bob Hope’s classic Road to Singapore (1940) revived the trope of seafaring stories set on a ship headed for the exotic tropical port, with no attempt or need for any sense of Malayan realism.69

The Real Singapore

Parallel to an analysis of the interplay of realism and romanticisation in cinematic history would be a consideration of the degree of fact and fantasy in portrayals of Singapore itself. All the Hollywood films shot on location were set in the tropical jungle, and locations in Singapore were chosen to depict the habitat of wild animals in Bring ’Em Back Alive, or a Malay village in Samarang. Whether accused of zoological “fakery” or showing a genuine Malay kampong in Bedok, both films were successful at the Singapore box office.70 The local setting and familiar faces seen on the big screen for the first time were enough to attract Singapore viewers, out of curiosity, if nothing else. The urban cinemagoers of Singapore who admired all things modern suddenly had rural, traditional life presented to them in a new light. This orientalist, cinematic glamorisation of Malay rural life presented an interesting juxtaposition against a recent movement to develop the kampong as a political symbol. The idea of the kampong, or small and generally rural settlement, had been closely associated with the way of life typical of the Malay community, and early Malay ethnic nationalists saw the kampong as a powerful representation of the Malay race.

Inspired by Kampong Bahru, the “Malay Agricultural Settlement”, which was built in 1899 as a model Malay settlement in Kuala Lumpur, the Singapore Malay Union petitioned the governor of the Straits Settlements in 1926 through their president, Mohamed Eunos Abdullah, who was Singapore’s leading Malay journalist and the community’s representative on the Straits Settlements Legislative Council. The association called for the purchase of land in Singapore where “Malays could build their own houses, plant a few fruit trees and live among their own people in the manner in which they were accustomed”.71 Like the obfuscation of reality in Hollywood films, this idealisation of the Malay kampong obscured the suburban location in Geylang of Kampong Melayu, as the completed settlement came to be called, as well as the residents’ occupations in the urban service industry rather than agriculture.72

Aside from the genre conventions of ethnographic and wildlife films, Singapore also played into other stereotypes, as with the early seafaring and illicit romance-themed films, which lacked authentic location footage. A range of strategies was employed in the representation of Singapore as a bustling Asian urban centre, which attracted critical responses within Singapore. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rich and Strange included only brief street scenes of downtown Singapore, most likely taken from stock footage.73 In 1936, Garnett filmed Singapore scenes to be used as rear projections for actors in a Hollywood studio, while Booloo reached further for authenticity in hiring over 200 extras – Malays, Chinese and Indian men, women and children, including “Chinese coolies and ricksha boys” to film train scenes at the railway station.74

By March 1936, Singapore audiences had seen enough Hollywood versions of Singapore to elicit a scathing critique in an editorial by The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on the “romanticising of our tropic city” that led film producers to desire making “films which would capture of that legendary lure of the East and magic of the tropics and all the other ingredients that go to make up the exotic novel” or reinforce the stereotype of “Singapore as a tropical playground for its amorous and loose-moralled inhabitants”. While reserving judgement on films still in production, for which backdrop footage had recently been filmed in Singapore (an obvious reference to Garnett, who had departed Singapore just two weeks before the writing of the editorial), the writer expressed that the “previous experience of the methods of Hollywood leads us to fear that it will be a far different Singapore from that which all of us know”. The writer listed realistic elements that did not fit the Hollywood imagination: “The fact that Singapore is a leading port of the world… is unlikely to be brought out, nor the rubber and produce godowns, dull-looking indeed but full of interest and romance, not the obvious poverty and diseases of ‘cheery Chinatown’, nor the essentially hardworking and thrifty Chinese, but only his ‘sinister’ brother, nor the harmless booths at the amusement parks, but an opium den”.75

A year and a half later, when Booloo was finally screened in Singapore, its concerted attempt at a realistic portrayal of Singapore urban life also came under fire. A letter to The Straits Times asked why the film was “trying to show the world that the Asiatic population of this city consists of nothing but hawkers, satai-men, poultry-farmers, ice-water sellers, pig rearers, and half-naked Chinese coolies”.76 The author, calling himself “No Hokum Here”, demanded to know if the authorities would “allow this sort of thing to be shown to the rest of the world”. It would seem that the author was defending the prestige of the island and, more specifically, the educated, middle-class and elite section of the Asian population. Singaporean audiences were astute enough to spot “fakery” as well as orientalist stereotypes in western films.

Conclusion

That Singapore was on Hollywood’s mental map of the world was clear, but whether that impression was much like the real Singapore was questioned by Singapore residents and critical cinemagoers. Over the period, there was a move towards more authentic representations, albeit sometimes in superficial ways such as using on-location footage as a filming backdrop in Hollywood studios. In particular, director Clyde Elliot managed to complete filming three location feature films between 1931 and 1938, each time attempting a deeper, more realistic depiction of Malayan society. But realism was not the most important factor when it came to the commercial considerations of Hollywood studios. Attempts to depict Asian society more accurately failed to make it to the big screen and misrepresentations of Singapore as a seedy maritime port-of-call or where life-threatening jungle encounters were a regular occurrence continued.

For audiences in Singapore, the release of these films were received with far less enthusiasm than the excitement of witnessing American cast and crew working on location during the films’ production. In contrast to their disdain for demeaning clichés shown in the films, when Singapore residents witnessed the constant stream of visitors from Hollywood, the global centre of modern popular culture, it gave them a strong sense of Singapore’s place in the modern world and their own identity as residents of this global port city.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Across to Singapore. Written by Ben Anne Williams and Ted Shane and directed by Nigh William. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928. 1:25, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0018618.

Albelli, A. “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger-Python Battle.” November 1932, accessed Modern Mechanix website.

Bloom J. Peter and Katherine J. Hagedorn. Film and Music Liner Notes for DVD Release of Legong: Dance of the Virgins (1935). (2003)

Bouse, Derek. Wildlife Films. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, 120. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 778.53859 BOU)

Braddell, Roland St. John. The Lights of Singapore. 3rd ed. London: Methuen, 1935, 122. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 BRA)

Buccione, R. “The Road to Singapore.” (blog), Macguffinmovies, 30 January 2012. Accessed 30 May 2013, http://macguffinmovies.wordpress.com/2012/01/30/the-road-to-singapore/

Buck, Frank and Ferrin L. Fraser. All in a Lifetime. New York: R. M. McBride & Company, 1941.

Sal of Singapore. Written by Dale Collins and Eliotte J. Clawson and directed by Howard Higgin. Pathe Exchange, 1928, 1:10. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0019348

Collins, Dale. The Sentimentalists. London: Heinemann, 1927.

East of Shanghai. Written by Dale Collins and Howard Higgin. British International Pictures, 1931. 1:23. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0023395.

Deacon, Desley. “Films As Foreign Offices: Transnationalism at Paramount in the Twenties and Early Thirties.” In Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective, ed. Ann Curthoys and Marilyn Lake. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2005.

Dirks, T. Dirks, History of Sex in Cinema: The Greatest and Most Influential Sexual Films and Scenes (Illustrated). (1930–1931). Accessed 11 June 2013, American Movie Classics. http://www.filmsite.org/sexinfilms4.html.

Booloo. Written and directed by Clyde E. Elliot. Paramount Pictures, 1938. 1:01. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029935.

Fatimah Tobing Rony. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 305.8 RON-[LYF])

Frost, Mark Ravinder and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow. Singapore: A Biography. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS])

Geiger, J. “Ernest B Schoedsack.” In The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, edited by Ian Aitken. New York: Routledge, 2013.

The Jungle Princess directed by Wilhelm Thiele and written by Cyril Hume and Gerald Geraghty. Paramount Pictures, 1936, 1:25. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0027830.

Samantha Gleisten. Chicago’s 1933–34 World’s Fair: A Century of Progress in Vintage Postcards (Illinois: Arcadia Publishing, 2002).

Hall, Mordaunt. “Dramatic Adventures of a Pearl Diver Featured in a Film at the Rivoli.” New York Times, 29 June 1933.

Road to Singapore. Directed by Victor Schertzinger and written by Don Hartman and Frank Butler. Paramount Pictures, 1940. 1:25. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032993.

Heider, G. Karl. Ethnographic Film. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Hyam, Ronald. Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990.

Jewell, B. Richard. “RKO Film Grosses, 1929–1951: The C. J. Tevlin Ledger.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 14, no. 1 (1994): 37–49.

Kahn, S. Joel. Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay World. Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Singapore University Press and NIAS Press, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 307.76209595 KAH)

Lai, Chee Keong. “The Native in Her Place: Hollywood Depictions of Singapore From 1940–1980.” Unpublished paper, 2001.

Landazuri, Margarita. “The Road to Singapore.” 1931. Accessed 30 May 2013, Turner Classic Movies.

The Letter. Written by W. Somerset Maugham and directed by Jean De Limur. Warner Bros, 1929. 1:05. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0020092.

Millet, Raphael. Singapore Cinema. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q791.43095957 MIL)

—. “Gaston Méliès and His Lost Films of Singapore.” BiblioAsia 12, no. 1. (April–June 2016)

Robins, Denise. Stranger Than Fiction: An Autobiography. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1965.

The Road to Singapore. Written by Denis Robins and Roland Pertwee and directed by Alfred E. Green. Paramount Pictures, 1931, 1:09. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0022321

Roff, R. William, The Origins of Malay Nationalism. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 320.54 ROF)

Solomon, Aubrey. The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A History and Filmography Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2011.

Tan, Fiona. “Four Accounts of a Shooting” (blog), Malaya Black and White, 10 April 2013. http://malayablackandwhite.wordpress.com/2013/04/10/four-accountsof- a-shooting/.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942). “The Film Invasion.” 20 March 1936, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

Toh, Hun Ping. Singapore Film Locations Archives. Accessed 21 July 2016. https://www.pic-hub.org/en/post/singapore-film-locations-archive.

—. Trade Winds. 1938. Accessed 10 May 2016. https://sgfilmlocations.com/2014/08/08/trade-winds-1938.

—. “Singapore Is the MacGuffin: Location Scouting in “Rich and Strange.” Sgfilmlocations. 18 January 2013. https://sgfilmhunter.wordpress.com/2013/01/18/rich-and-strange/.

Une Cinephile “Road to Singapore.” (blog), 26 January 2012. Accessed 30 May 2013. http://unecinephile.blogspot.com/2012/01/road-to-singapore-1931.html.

Van der Heide, William. Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 791.43 VAN)

Vieira, A. Mark. Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 1999.

Who’s Who in Malaya 1939: A Biographical Record of Prominent Members of Malaya’s Community in Official, Professional and Commercial Circles. Singapore: Fishers Ltd., 1939. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 9595 WHO-[RFL])

Williams, Ben Ames. All the Brothers Were Valiant. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1919.

Wing, Ward. Shark Woman, a.k.a. Samarang. Alpha Home Entertainment. 2012; repr., 1933.

Wolfe, Charles. “The Poetics and Politics of Nonfiction: Documentary Film.” In Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939, edited by Tino Balio. History of the American Cinema 5. New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1996. (From National Library Singapore, call no. 791.430973 HIS)

Wright, H. Nadia. Respected Citizens: The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia. Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.891992 WRI)

NOTES

-

“Singapore May Become Hollywood of East,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 9 January 1936, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Film Invasion,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 20 March 1936, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2009), 135. (From National Library Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]) ↩

-

Raphael Millet, Singapore Cinema (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006), 19 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q791.43095957 MIL); Raphael Millet, “Gaston Méliès and His Lost Films of Singapore,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 1 (April–June 2016); Toh Hun Ping, Singapore Film Locations Archives, accessed 21 July 2016, https://www.pic-hub.org/en/post/singapore-film-locations-archive. ↩

-

Millet, Singapore Cinema, 143–44; Lai Chee Keong, “The Native in Her Place: Hollywood Depictions of Singapore From 1940–1980,” unpublished paper, 2001. Prints of these films are not easily available, with some existing only as non-circulating archival copies. The only print of Sal of Singapore, which is held in the UCLA library, is currently undergoing preservation and is inaccessible to researchers, while the sole known copy of The Crimson City was rediscovered in 2010 in the archives of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina. See Larry Rohter, “Footage Restored to Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’,” New York Times, 4 May 2010, accessed 21 May 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/05/movies/05metropolis.html. ↩

-

Toh Hun Ping, “Singapore Is the MacGuffin,” Sgfilmlocations, 18 January 2013, https://sgfilmhunter.wordpress.com/2013/01/18/rich-and-strange/. ↩

-

Across to Singapore, written by Ben Anne Williams and Ted Shane and directed by Nigh William (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928), 1:25, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0018618; Sal of Singapore, written by Dale Collins and directed by Howard Higgin (Pathe Exchange, 1928), 1:10, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0019348; East of Shanghai, written by Dale Collins and Howard Higgin (British International Pictures, 1931), 1:23, http:// www.imdb.com/title/tt0023395. (Rich and Strange was the original release title in the UK, the film was renamed for the US market) ↩

-

The Road to Singapore, written by Denis Robins and Roland Pertwee and directed by Alfred E. Green (Paramount Pictures, 1931), 1:09, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0022321; Denise Robins, Stranger Than Fiction: An Autobiography (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1965); The Letter, written by W. Somerset Maugham and directed by Jean De Limur (Warner Bros, 1929), 1:05, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0020092. ↩

-

Somerset Maugham’s visits to Singapore took place in 1921 and 1925, and Dale Collins’ sojourns in 1922 and 1926, see “Social and Personal,” Straits Times, 4 August 1921, 6; “Cruise of the Speejacks,” Straits Times, 20 June 1922, 7; “Mr. Somerset Maugham,” Straits Times, 9 November 1925, 9; “Social and Personal,” Straits Times, 27 January 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Round the World in a Yacht,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 20 June 1922, 7 (From NewspaperSG); Dale Collins, The Sentimentalists (London: Heinemann, 1927) ↩

-

“Mr. Somerset Maugham”; “The Plays and Public,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 10 November 1925, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Fiona Tan, “Four Accounts of a Shooting” (blog), Malaya Black and White, 10 April 2013, http://malayablackandwhite.wordpress.com/2013/04/10/four-accountsof- a-shooting/; “An Occasional Note,” Straits Times, 13 October 1926, 8 (From NewspaperSG); London: Public Record Office, “Public Prosecutor vs Ethel Mabel Proudlock,” 7 June 2011 (Criminal Case No. 22/11, C.O. 273/274), accessed 23 May 2013, MalayaBlack and white Files, http://malayablackandwhite.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/co273-374-proudlock-evidence.pdf. ↩

-

Ben Ames Williams, All the Brothers Were Valiant (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1919), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25885/25885-h/25885-h.htm; R. Buccicone, “The Road to Singapore,” (blog), Macguffinmovies, 30 January 2012, accessed 30 May 2013, http://macguffinmovies.wordpress.com/2012/01/30/the-road-to-singapore/; Margarita Landazuri, “The Road to Singapore,” 1931, accessed 30 May 2013, Turner Classic Movies; Une Cinephile “Road to Singapore,” (blog), 26 January 2012, accessed 30 May 2013, http://unecinephile.blogspot.com/2012/01/road-to-singapore-1931.html. ↩

-

Ronald Hyam, Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 179–80. ↩

-

“Slump in the Tiger Trade,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 21 September 1932, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“$1,000,000 Picture Maker in Singapore,” Straits Times, 5 April 1933, 12 (From NewspaperSG); Charles Wolfe, “The Poetics and Politics of Nonfiction: Documentary Film,” in Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939, ed. Tino Balio History of the American Cinema 5 (New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1996), 380. (From National Library Singapore, call no. 791.430973 HIS) ↩

-

“Slump in the Tiger Trade”; “Bring ‘Em Back Alive,” Straits Times, 17 November 1932, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

McGuire was writing in the magazine, Outdoor Life, as reported in “Bring ‘Em Back Alive”; See also “Another Critic of Mr. Frank Buck,” Straits Times, 9 April 1933, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pictures and How They Are Made,” Straits Times, 8 December 1932, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“When Jungle Gangsters Meet,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 3 October 1932, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A. Albelli, “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger-Python Battle,” November 1932, accessed Modern Mechanix website. ↩

-

In a press interview, Buck admitted the close-up scenes were filmed at Jurong Road, Singapore; see “$1,000,000 Picture Maker in Singapore.” He was also reported to have had animal camps off Orchard Road, on the fringes of the downtown zone, and in the residential suburb of Katong; see Frank Buck and Ferrin L. Fraser, All in a Lifetime (New York: R. M. McBride & Company, 1941), 108. ↩

-

Wild Cargo, directed by Armand Denis and written by Frank Buck and Courtney Ryley Cooper (Amedee J. Van Beuren, 1934), 1:36, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0025991; Fang and Claw, directed by Frank Buck and written by Frank Buck and Ferrin Fraser (Amedee J. Van Beuren, 1935), 1:13, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0026337; Jungle Menace, directed by Harry L. Fraser and George Melford and written by George M. Merrick, Sherman L. Lowe and Harry O, Hoyt ( Robert Mintz (executive) and Louis Weiss, 1937), 5:08, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029071; Jungle Cavalcade, directed by William C. Ament, Armand Denis and Clyde E. Elliott and written by Edward Anthony, Frank Buck and Courtney Ryley Cooper (Walton C. Ament, 1941), 1:16, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0033775; Jacare directed by Charles E. Ford and written by Thomas Lennon (Jules Levey, 1942), 1:05, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0034908; Tiger Fangs, directed by Sam Newfield and written by Arthur St. Claire (Producers Releasing Corporation, 1943), 59m, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0036439. ↩

-

Van Dart, Frank Buck’s Jungleland, 1939, accessed 8 January 2018, http://www.1939nyworldsfair.com/worlds_fair/wf_tour/zone-7/jungle_land.htm; Samantha Gleisten, “Frank Buck’s Jungle Camp on the Midway Broadwalk,” in Chicago’s 1933–34 World’s Fair: A Century of Progress in Vintage Postcards (Illinois: Arcadia Publishing, 2002), 121; “Big Game Hunting and “Wild Animal” Spectacles in the Wolfsonian Museum Collection,” accessed 8 January 2018, Wolfsonian-FIU Library, https://wolfsonianfiulibrary.wordpress.com/2015/07/31/big-game-hunting-and-wild-animal-spectacles-in-the-wolfsonian-museumcollection. ↩

-

Derek Bouse, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 120. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 778.53859 BOU); “A Real Jungle Film,” Singapore Daily News, 5 December 1932, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Out of the Sea” off Singapore,” Straits Times, 9 October 1932, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Desley Deacon, “Films As Foreign Offices: Transnationalism at Paramount in the Twenties and Early Thirties,” in Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective, ed. Ann Curthoys and Marilyn Lake (Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2005), 145; Karl G. Heider, Ethnographic Film (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), 25–26. ↩

-

Heider, Ethnographic Film, 25; J. Geiger, “Ernest B Schoedsack,” in The Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, ed. Ian Aitken (New York: Routledge, 2013) ↩

-

Samarang: Highlights of the film. (1933, September 29). Alhambra Magazine. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Nadia H. Wright, Respected Citizens: The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia (Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing, 2003), 293. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.891992 WRI) ↩

-

“Samarang: Highlights of the Film,” Alhambra Magazine, 29 September 1933; Who’s Who in Malaya 1939: A Biographical Record of Prominent Members of Malaya’s Community in Official, Professional and Commercial Circles (Singapore: Fishers Ltd., 1939) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 9595 WHO-[RFL]); “Thrills by Edgar Wallace,” Straits Times, 3 October 1932, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Samarang: Highlights of the Film.” ↩

-

“Trial of Malay Film Talent,” Singapore Daily News, 10 October 1932, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Telling the World,” Alhambra Magazine, 29 September 1933. ↩

-

“Pearl and Shark Story Filmed Here,” Malaya Tribune, 1 December 1932, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mortal Combat of Tiger Shark and Octopus in “Samarang” Is Remarkable Camera Record,” Alhambra Magazine, 20 September 1933. ↩

-

Mordaunt Hall, “Dramatic Adventures of a Pearl Diver Featured in a Film at the Rivoli,” New York Times, 29 June 1933. ↩

-

Ward Wing, Shark Woman, a.k.a. Samarang. Alpha Home Entertainment (2012; repr., 1933) ↩

-

Wing, Shark Woman. ↩

-

“Shocked by Bathers,” Straits Times, 18 March 1934, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T. Dirks, History of Sex in Cinema: The Greatest and Most Influential Sexual Films and Scenes (Illustrated), accessed 11 June 2013, American Movie Classics, http://www.filmsite.org/sexinfilms4.html. ↩

-

Peter J. Bloom and Katherine J. Hagedorn, Film and Music Liner Notes for DVD Release of Legong: Dance of the Virgins (1935). (2003) ↩

-

Fatimah Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 148. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 305.8 RON-[LYF]) ↩

-

Mark A. Vieira, Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood (New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 1999), 63; Richard B. Jewell, “RKO Film Grosses, 1929–1951: The C. J. Tevlin Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 14, no. 1 (1994): 39. ↩

-

“Page 7 Advertisements Column 3: ‘Devil Tiger’,” Straits Times, 11 May 1934, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Man-Eater’,” Straits Times, 17 November 1932, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Malayan Saturday Post, 25 March 1933, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Deep Mystery of ‘Man-Eater’,” Straits Times, 21 May 1933, 9; “Notes of the Day: “Devil” Insects,” Straits Times, 23 May 1934, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Devil Tiger’,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 11 May 1934, 2 (From NewspaperSG); Aubrey Solomon, The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A History and Filmography (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2011), 190. ↩

-

“New Film of Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 20 March 1936, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Jungle Princess directed by Wilhelm Thiele and written by Cyril Hume and Gerald Geraghty (Paramount Pictures, 1936), 1:25, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0027830. ↩

-

William Van der Heide, Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Cultures (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002), 128 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 791.43 VAN). The Jungle Princess is also commercially available on DVD. ↩

-

“‘Jungle Princess’ With a Lisp,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 1 April 1937, 2; “Page 7 Advertisements Column 1: ‘The Jungle Princess’,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 2 April 1937, 7; “Page 7 Advertisements Column 2: ‘The Jungle Princess’,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884– 1942), 8 July 1937, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Van der Heide, Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film, 128. ↩

-

Booloo written and directed by Clyde E. Elliot (Paramount Pictures, 1938), 1:01, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029935. ↩

-

“Real Malayan Jungle for Screen,” Straits Times, 18 July 1937, 5; “Ten Tons of Film Kit for Jungle Picture,” Straits Times, 17 August 1937, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 5 August 1937, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Movie Cameras Click in Jungle,” Straits Times, 21 November 1937, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dorothy Lamour Type Sought,” Straits Times, 5 August 1937, 12; “‘Booloo’ Girl Not Found Yet,” Straits Times, 19 September 1937, 5; Crux Australis, “Notes of the Day: Coy Officers,” Straits Times, 20 November 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Where Are “Booloo” Shots of Javanese Girl?” Straits Times, 11 September 1938, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T. F. Brady, “Hollywood’s Story Marts Dry Up,” New York Times, 24 May 1942, x3. ↩

-

“Fred Pullen Protests to Hollywood,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 10 September 1938, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hollywood Celebrities Arrive in Luxury,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 29 February 1936, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Toh Hun Ping, Trade Winds, 1938, accessed 10 May 2016, https://sgfilmlocations.com/2014/08/08/trade-winds-1938. ↩

-

Road to Singapore directed by Victor Schertzinger and written by Don Hartman and Frank Butler (Paramount Pictures, 1940), 1:25, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032993. ↩

-

Roland St. John Braddell, The Lights of Singapore (London: Methuen, 1935), 122. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 BRA) ↩

-

William R. Roff, The Origins of Malay Nationalism (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994), 193. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 320.54 ROF) ↩

-

For a fuller discussion of the Kampong Melayu project, see Joel S. Kahn, Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay World (Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Singapore University Press and NIAS Press, 2006), 4–28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 307.76209595 KAH) ↩

-

Toh, “Singapore Is the MacGuffin.” ↩