The Japanese Army’s Covert Operation In Singapore And The Riau Islands In The Early 20th Century

By Yosuke Watanabe

INTRODUCTION

As is well known, Japan started their invasion of Southeast Asia on 8 December 1941, when the Japanese Imperial Army landed at Kota Bharu in British Malaya. However, amongst historians, debate continues regarding when the Japanese state officially adopted a policy of southward military expansion into Southeast Asia. Broadly speaking, their conclusions differ depending on how they define “the South” in reference to Asia.

For one, researchers who understand the term as referring to southern China have argued that the Japanese state adopted a doctrine of southern expansion (南進論; Nanshinron) in the latter half of the 1890s. For evidence, Ito Mikihiko has pointed to the Xiamen Incident in 1900, when a Japanese temple, Higashi Hongan-ji, in Xiamen, China, was destroyed in an arson attack. After the cession of Taiwan in 1895, Japan had begun eyeing the province of Fujian, where Xiamen is located. Recognising the arson attack as an opportunity to expand into southern China, it dispatched a small naval brigade to the Chinese city. However, Britain responded by sending a warship and naval brigade, and Japan agreed to immediately withdraw.1

On the other hand, historians who define “the South” in Asia as encompassing Southeast Asia and the South Pacific islands hold a different view. Hatano Sumio, for instance, argues that southern expansion as a Japanese state policy began in 1914, when Japan first occupied a German colony in the South Pacific as part of a military campaign during the First World War. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that full-scale southern expansion did not commence until the 1930s. 2

However, scholars who understand “the South” in Asia as Southeast Asia have mostly argued that Japan did not officially adopt its policy of southern expansion until 1936. Yano Toru points out that two doctrines formulated on 7 August 1936 were important for the cause of Japanese expansionism in Southeast Asia: the Fundamentals of National Policy (Kokusaku No Kijun) and the Imperial Foreign Policy Doctrine (Teikoku Gaiko Hoshin). The former, in describing Japan’s southward expansion, states that “Japan expects its national and economic advance into the South, especially into Southeast Asia, through gradual and peaceful means”. Similarly, the latter underscores the importance of the South for Japan: “The South Seas…is a strategic area for world trade and the vital region for the Empire’s industry and defence”.3 Both policies are generally understood to be the earliest official Japanese documents to stipulate a policy of expansion into Southeast Asia. 4

On the whole, most historians agree that Japan’s expansionist policy towards Southeast Asia began no earlier than in the 1930s. They also largely maintain that the Japanese navy played a major role in planning the region’s invasion, for two important reasons. First, the navy’s fleets and aircraft needed oil for fuel. As the US–Japan relationship deteriorated, the navy began to consider using military measures to advance into Southeast Asia to secure oil and other natural resources. 5 The second factor was the long-standing rivalry between the Japanese navy and army for limited military funding. Once the army had established the puppet state of Manchukuo in China in 1932, it began demanding more of Japan’s military budget in order to defend the puppet state. At that time, the Japanese navy first proposed its plan to invade Southeast Asia in a bid to keep its budget intact.6

By the end of 1936, as the Washington and London naval treaties approached their expiration, an arms race was expected to begin between Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. To address the impending situation, the Japanese government formulated the Fundamentals of National Policy and the Imperial Foreign Policy Doctrine. It began planning to seize oil fields on Borneo and Sumatra, among other sites, in case oil imports to Japan were blocked. 7 In that sense, Japan’s plan to invade Southeast Asia does indeed seem to have first surfaced in the 1930s.

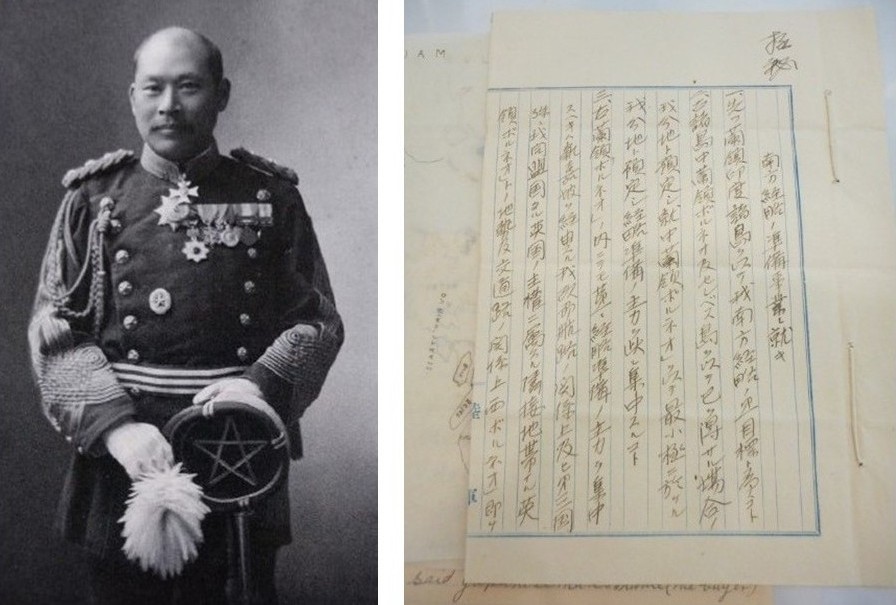

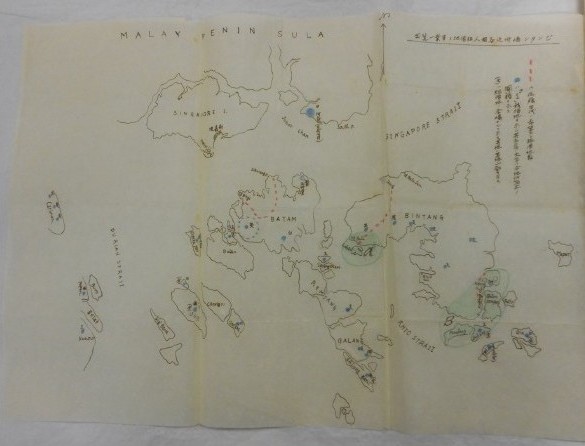

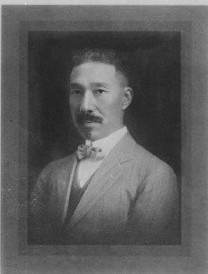

However, several years ago, primary sources that appear to erode this argument were found by Singaporean collector Lim Shao Bin in a shop for used books in Tokyo, Japan. The letters and contracts suggest that long before the 1930s, some staff members of the Japanese army had already devised a plan to invade and colonise Southeast Asia step-by-step. Among those materials, a letter written by Major General Utsunomiya Taro (宇都宮太郎), then chief of the Second Division, Department of the Japanese Army General Staff, titled “On the Preparation for the Nanpo Operation” (南方経略の準備事業に就き) and dated 1 August 1910, is of particular importance. The letter contains Utsunomiya’s master plan to colonise Southeast Asia and even includes concrete directions addressed to Reserve Colonel Koyama Shusaku (小山秋作), Utsunomiya’s former colleague and personal agent, for a secret operation of the Japanese army. According to these documents, Utsunomiya had dispatched Koyama to Singapore to conclude land lease contracts with landowners on the nearby Riau Islands to build military outposts. Nevertheless, the question remains as to how such newly found materials should be interpreted.

(Right) Utsunomiya’s letter, “On the Preparation for the Nanpo Operation”. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore.

Through studying this set of materials, this paper seeks to resolve two dilemmas. First, it examines how and why Utsunomiya’s Nanpo operation was conducted. Because no literature has ever discussed Japan’s plans for invasion made in the 1910s, including the Nanpo operation, revealing the developments of the operation can illuminate that area of study. Second, the paper examines the impact of the Nanpo operation on the conventional assumptions among historians: that Japan’s expansionist policy towards Southeast Asia began in the 1930s at the earliest, and that the Japanese navy played a vital role in establishing that policy. This paper seeks to analyse whether these beliefs should be reconsidered in light of the discovery of the Nanpo operation not as a Japanese naval operation but as Army General Utsunomiya’s secret land-leasing operation, which occurred long before the 1930s. It also traces the origins of the Nanpo operation and presents its developments in chronological order.

Initial Success of the Nanpo Operation

Utsunomiya initiated the covert Nanpo operation following information shared by Tashiro Kyohachi (田代強八) on 26 April 1910 in Tokyo about the possibility of leasing land on the Riau Islands. At the time, Tashiro was serving as financial adviser to Dao Anren (刀安仁) in Ganya (present-day Yingjiang) in Yunnan province, China. When Tashiro visited Utsunomiya in Tokyo, he told Utsunomiya that he had provisionally agreed to lease land on some islands close to Singapore in the Dutch East Indies and hoped that Utsunomiya would complete the land-leasing operation. Responding affirmatively, Utsunomiya said, “This land lease might become an initial step to serve a bigger purpose”. 8

On 12 May, Utsunomiya handed over a set of documents concerning the plan to lease land in the Riau Islands to Army Minister Terauchi Masatake (寺内正毅) and asked him to issue his judgement of the plan at their next meeting. Terauchi responded that he would relay the documents to Minister of Communications Goto Shinpei (後藤新平), and encouraged Utsunomiya to meet Goto. Two days later, Utsunomiya visited Goto and shared his plan. Meanwhile, Terauchi’s secretary, Yoshida, also visited Goto to show him Utsunomiya’s lease documents. In response to Utsunomiya, Yoshida conveyed Terauchi’s opinion that it would be better to remain uninvolved in leasing land on the islands for the time being.

Despite receiving a negative reply from the army minister, Utsunomiya persisted in his vision, believing the operation warranted further research. 9 He wrote a letter dated 25 May 1910, to Lieutenant Matsumoto Gozaemon (松本五左衛門), a military attaché to the Japanese consulate in Singapore, ordering him to conduct research about leasing land on the Riau Islands. 10 In response, on 23 June, Matsumoto issued a report stating that Japan had some opportunities to lease land there, though the terrain was not ideal. 11

Around the same time, Utsunomiya began recruiting another agent for the planned operation – a former colleague, Reserve Colonel Koyama Shusaku. On 18 June, when Koyama was visiting Utsunomiya at home, Utsunomiya expressed the necessity of colonising Southeast Asia.12 Two days later, Koyama visited Utsunomiya’s office and went over several documents on Southeast Asia. Perhaps as a result of such efforts, Koyama responded with great interest when Utsunomiya asked for his help to execute the landleasing operation.13

Shortly after, Utsunomiya wrote a letter to Koyama titled “On the Preparation for the Nanpo Operation” dated 1 August 1910. As previously mentioned, this letter contained Utsunomiya’s master plan to colonise Southeast Asia as well as concrete directions addressed to Koyama. It identifies the Dutch East Indies as the chief target for future Japanese territory, where, the letter claims, the Kapuas and Sambas river valleys in West Kalimantan were considered to be best for leasing land due to their proximity to British Borneo (present-day Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei). Banking on the Anglo-Japanese Alliance (1902–23), Japan hoped that the British would support their expansion into West Kalimantan. Moreover, the lands were thought to be strategically located, along maritime routes between Japan and Europe. To secure these areas, the letter continues,

military outposts near Singapore would be pivotal. As a first step, Utsunomiya suggested two desirable areas in which to lease land: some islands located to the west of Pulau Bintan, and some islands to the south of it.14 Given these contents, the letter reveals that some Japanese army staff had already envisioned expanding Japan’s colonies into Southeast Asia as early as the second decade of the 20th century.

To realise the master plan, Tashiro and Koyama were dispatched to Singapore on 6 August, on the same boat departing Kobe, Japan. They had visited their boss separately four days earlier and at different locations, to bid him goodbye. This suggests that the two agents did not have a close relationship.15 Later, Tashiro ran into conflict with Koyama Matsumoto. Tashiro was unable to conclude any land lease agreements, whereas Koyama succeeded in signing two contracts.16

Although Utsunomiya provided Tashiro with approximately 700 yen (equivalent to roughly 2,177,000 yen in 2015)17 and Koyama with 2,000 yen (equivalent to 6,220,000 yen in 2015) before their departure, it was a continual struggle to raise funds for the operation. To raise the 700 yen for Tashiro, Utsunomiya had had to ask Lieutenant General Fukushima Yasumasa (福島安正) to divert funds from Shinbu Gakko (振武学校), a special school for Chinese students.18 When Matsumoto and Koyama sent a telegraph, dated 25 October 1910, requesting an additional 5,000 yen (equivalent to 15,550,000 yen), Utsunomiya again turned to Fukushima for funding, but was only able to obtain 2,000 yen. He borrowed the remaining 3,000 yen from a company called Meiji Shogyo (明治商業) by furnishing his private estate as security. On 26 October, Utsunomiya visited Minister of Communications Goto to ask whether he could provide him with 3,000 yen. Although Goto did not reply immediately, he ultimately prepared the requested sum from a bank called Dai Jugo Ginko (第十五銀行).19 Utsunomiya faced an uphill task raising funds for the Nanpo operation because it had not secured the approval of Army Minister Terauchi.

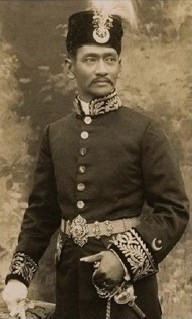

In time, Koyama’s efforts brought about two contracts, both signed on 1 November 1910. One was between Uyeda Ushimatsu (上田丑松), a permanent Japanese resident in the Dutch East Indies who was also Koyama’s deputy, and Ki Hiong Tje (紀芝發), a Chinese landowner of Pulau Ayer Raja (Airraja in the present-day spelling);20 and the other between Uyeda and Abdul Rahman Shah, the sultan of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, who owned the islands (or pulau) of Kila, Momoi and Awi near Pulau Ayer Raja.21

Pulau Ayer Raja, the largest island of the four leased to Uyeda, is situated south of Batam Island. According to the mentioned contract, the island was to be leased for 2,500 Straits dollars, but after owner Ki had received 500 dollars as a down payment,22 he departed for China, never to return to the Riau Islands. As a result, the transfer of Pulau Ayer Raja’s surface rights to Uyeda was not completed.23

As for the three small islands of Kila, Momoi and Awi, the transfer of surface rights was successfully executed after Uyeda paid the sultan 250 dollars.24 On 4 November, Koyama concluded another contract with Uyeda, stipulating that Uyeda would transfer his surface rights on the four islands to Koyama unconditionally once Koyama obtained the permanent residency status in the Dutch East Indies. As a result, Koyama reserved the right to issue decisions regarding the leasing of land and to use all proceeds from the land, and Uyeda promised not to intervene. Koyama was to pay Uyeda 2,750 dollars as a fee to purchase the surface rights to the four islands at Uyeda’s request, and Koyama, in return, would pay Uyeda 1,000 dollars as a reward once he obtained permits to lease land on the four islands.25

In that way, Koyama managed to acquire the right to use pieces of land on Kila, Momoi and Awi, all situated near Singapore. But why did Sultan Abdul Rahman, the owner of the three islands, virtually cede his land to a Japanese individual? The next section examines the political difficulties faced by the sultan at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Sultan’s Need for Japanese Help

Sultan Abdul Rahman was a descendant of the royal family of the Melaka Sultanate, which had been established circa 1400. When the Portuguese conquered the Sultanate’s capital, Melaka, in 1511, the royal family fled to Johor and established a new kingdom, the Johor Sultanate, with territory extending from Johor to the Riau and Lingga Islands. In 1824, Great Britain and the Netherlands agreed to draw a boundary between Singapore and the Riau Islands, with the British sphere of influence to the north and the Dutch to the south. As a result, the Johor Sultanate was split, and the Sultanate on the south was named the “Riau-Lingga Sultanate” or “Riau Sultanate”.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Dutch extended their direct rule throughout the Dutch East Indies, seizing control from the remaining independent local rulers.26 They occupied southwestern Sulawesi in 1905–06, subjugated Bali with military campaigns in 1906 and 1908, and conquered the independent kingdoms in Maluku, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Nusa Tenggara. The Riau-Lingga Sultanate was no exception.27

At the time, frequent clashes between the Riau court and the Dutch administration prompted the Dutch to contemplate assuming direct control over Riau-Lingga. In response, the Riau court began seeking powerful allies, and a particularly viable candidate was Japan, a rising nation that had recently defeated a Western power in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) and belonged to the same Eastern cultural sphere. As early as 1905, the Riau court had dispatched Raja Hitam, a member of the court, to Singapore. According to an anonymous letter to the Dutch colonial government, Raja Hitam’s reason for visiting Singapore had been to negotiate the handing over of Riau-Lingga to Japan in order to solicit Japanese assistance. Sultan Abdul Rahman, on the advice of his ministers, refused to sign a new political agreement with the Dutch, claiming that it would deprive him of any real authority. In the struggle against colonial masters, he wanted Japan on his side for counterbalance.28 With this objective in mind, Sultan Abdul Rahman thus allowed the lease of land on his islands to Uyeda.

Less than four months later, however, in February 1911, the sultan was deposed by the Dutch and exiled to Singapore. In October 1912, the Riau court wrote a letter to the Japanese emperor asking for his personal intervention so that Riau could come under Japanese rule and the sultan restored to his former position. The Japanese government could not, however, countenance such an anti-Dutch petition, given its basic policy of cooperating with Western powers at the time. Although Raja Hitam, a member of the Riau court, was dispatched to Tokyo twice, in 1912 and 1913, there are no records showing that he met with any prominent Japanese politicians or government officials during those visits.29

Opposition to the Nanpo Operation and Utsunomiya’s Response

Among the Japanese politicians and officials who did not support Utsunomiya’s anti-Dutch campaign, was the Japanese Vice Consul in Singapore, Iwaya Jokichi (岩谷譲吉), who squarely opposed the operation to lease land on nearby islands, for several reasons. Although Matsumoto, a military attaché to the Japanese consulate in Singapore, explained that Koyama and Uyeda had no intention of using the lands for military purposes but only for rubber planting, Iwaya was not convinced. He argued that as the leased islands were situated in a strategically vital area – the Melaka Straits – and military men such as Koyama and Matsumoto were involved, suspicions might be raised that the islands would ultimately be used for one military purpose or other.

In parallel, the Dutch were becoming increasingly sensitive to Japanese movements in the Dutch East Indies,30 partly because the ousted Riau court was actively seeking Japanese assistance to be reinstated. The deposed sultan had, on several occasions, met with Japanese representatives privately and even written to the commander of the Japanese squadron in Singapore, whom he had previously met. Given the sultan’s various appeals for Japanese intervention, the Dutch became deeply concerned, and civilians entertained fears of a war between the Netherlands and Japan, to the extent that many Riau Malays fled to Singapore.31 Under such circumstances, the Nanpo operation would have affected the economic activities of the Japanese in the Dutch colony.

Troubled by the possible negative ramifications of the Nanpo operation, Iwaya sent a report on the matter to Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro (小村寿太郎) on 7 January 1911, and in turn, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs made an inquiry with the Army Ministry on 1 February. In response, Army Deputy Minister Ishimoto Shinroku (石本新六) asked Army Deputy Chief of Staff Fukushima Yasumasa in an official letter dated 7 February, whether it was accurate to state that Koyama’s land-leasing operation had received the army staff’s informal consent. Eight days later, when Fukushima replied in the negative, stating that the army staff had “nothing to do with” the operation, his reply was relayed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and on 20 February the case was closed.32 However, because the Nanpo operation had been initiated by Utsunomiya, a chief of the general staff, with financial support from Fukushima and Goto, it is clearly inaccurate to say that the army staff had “nothing to do with” the operation.

On 1 February, the day when the inquiry into the Nanpo operation was opened by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Utsunomiya visited Goto to show him a copy of the letter he had written to Koyama, which was titled “On the Preparation for the Nanpo Operation”. The following day, he visited Goto again, to inform him that he would send Koyama to the minister in a few days. On 3 February, Utsunomiya invited Koyama to his office to announce that he would be transferring his surface rights to the four islands over to Koyama. On 10 February, Utsunomiya drafted a contract to this effect – which he dated 1 February – in order to prove that he had had “nothing to do with” the Nanpo operation.33 As a result, he now possessed documentary evidence and could use the contract to explain his innocence if necessary.

The question remains why army staff members lied to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and concealed the land-leasing operation on the Riau Islands. Of course, Army Minister Terauchi, as mentioned, did not support Utsunomiya’s anti-Dutch operation. For most in the government, Japan’s cooperation with Western powers, including the Netherlands, was perhaps more important than Japanese colonial expansion to small islands in Riau. Utsunomiya had continued executing the Nanpo operation even after Terauchi implied that he was not in agreement. As such, the actors involved in the operation perhaps decided to conceal the truth by insisting that the lease agreements for the land had been concluded for purely economic purposes; by doing so, the general staff involved in the Nanpo operation, including Utsunomiya and Fukushima, could avoid responsibility for such a controversial operation. In that way, the covert land-leasing operation became a truly secret one known only to the army, for it was not an official policy of the Japanese government.

Social Background of the Rise of Japan’s Expansionist Policy in Southeast Asia

In the 1910s, discourse concerning Japanese expansionism in Southeast Asia (南進論) prevailed in Japan. For instance, Takekoshi Yosaburo’s (竹越与三郎) travelogue of Southeast Asia and South China, Lands of the South, or Nangoku-ki (南国記), was a bestseller throughout the decade. In his book, Takekoshi claims that the Japanese emperor should be recognised as a saviour of Asia and Japan itself as the succour of all Asian peoples. Characterising the Netherlands, by contrast, as a tenth-rate power that could do nothing to help the people under its rule, Takekoshi argues that Japan should therefore take the responsibility to free the Malay people from their miserable colonial condition. Furthermore, he advocates not merely Japanese expansion but the full seizure of the Dutch East Indies. As the proponent of such ideas, Takekoshi was singled out by the Dutch administration for close monitoring.34

In Japan, this discourse was embraced. Seeing that Japan had allied with Great Britain in 1902 and defeated Russia in 1905, many Japanese began to regard themselves as members of a first-rate power on the world stage. At the same time, however, they lacked confidence in Japan’s capacity to compete with other powerful countries such as Britain and the United States and yearned for someone who dared to articulate a vision of greatness for Japan and its people. Takekoshi’s aggressive expansionism was received well in that social atmosphere.35

Conclusion

This paper has discussed the three principal reasons for the Nanpo operation. First, the Riau court needed Japanese assistance. As mentioned, since 1905 the court had weathered frequent conflicts with the Dutch when the Dutch Resident in Tanjong Pinang, Bintan Island, attempted to render the court a nominal sultanate. Amid such circumstances, Sultan Abdul Rahman agreed to lease land to a Japanese individual in the hopes of receiving Japanese assistance against the Dutch.

Second, Major General Utsunomiya Taro was an aggressive expansionist, one who believed that Western powers would become Japan’s real enemies in the long run, and perhaps that disposition explains why he conducted the Nanpo operation. Indeed, Utsunomiya’s diary reveals numerous aggressive remarks, including his 25 April 1900 entry, where he criticised the general populace of the army as pacifists and advocates for military development.36 In 1912, Utsunomiya also strongly supported then Army Minister Uehara Yusaku’s (上原勇作) endorsement of the deployment of two divisions of the Japanese army into its colony of Korea.37

Another of Utsunomiya’s beliefs was that an ethnic conflict between the East and West would break out and that Japan should therefore ally with other Asian countries against Western powers. For example, Utsunomiya’s February 1897 report on his survey trip to China and Korea submitted to the chief of the general staff stated that it would be prudent to prepare for such a conflict by allying with China and Korea.38 Similarly, on 25 July 1907, when Utsunomiya received six former Korean ministers and military officers who had been exiled, he shared his ideas with them, including his original Western powers.39 Taken together, such remarks attest to Utsunomiya’s perception that Western powers would be Japan’s future enemies. Perhaps due to such thinking, Utsunomiya persuaded Koyama to conduct the anti-Dutch Nanpo operation, even despite its lack of support from the mainstream of the army and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Third, in the 1910s, as exemplified by Takekoshi’s Lands of the South, a discourse concerning Japanese expansionism toward Southeast Asia dominated in Japan. However, because Japanese people were not confident in competing against the British Empire and the United States, they yearned for someone who would give voice to a rosy vision of Japan in the coming years.40 Takekoshi’s aggressive expansionism was received well in that social milieu, and Utsunomiya and his colleagues, not entirely immune to such ideas, sought to carry out the Nanpo operation.

Ultimately, this paper answers the question of how the Nanpo operation affects the accepted understanding of Japan’s expansionist policy towards Southeast Asia. Because the Nanpo operation was not adopted as the official policy of the Japanese government, its impact on that understanding among historians has not been particularly strong. It nevertheless warrants attention, because the origin of the idea of a Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia can be traced to the operation. Particularly, Utsunomiya’s idea that Japan should civilise other parts of Asia under Japanese leadership in order to counter Western powers can be seen as a prototype of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere propagandised when Japan invaded Southeast Asia in the 1940s.

In sum, Japanese army staff already had a master plan to colonise Southeast Asia as early as the beginning of the 20th century. That revelation suggests that the origin of the doctrine of Japanese militarism and expansionism in Southeast Asia can be traced back to the late Meiji period.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gracie Lee and Joanna Tan of the National Library for their support, and Prof Yamada Akira (Meiji University) for his valuable comments on the manuscript. I would also like to thank Prof Takashima Nobuyoshi (University of the Ryukyus) and Lim Shao Bin (donor of the Lim Shao Bin Collection) for their recommendation and help in my application for the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship. Finally, I would like to thank the Fellowship for the financial support provided.

REFERENCES

Andaya, Watson Barbara. “From Rum to Tokyo: The Search for Anticolonial Allies by the Rulers of Riau, 1899–1914.” Indonesia 24, no. 24 (October 1977): 136, 148, 152. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Asada, Sadao 麻田貞雄_._Ryō taisen-kan no hi kome kankei ― kaigun to seisaku kettei katei 両大戦間の日米関係―海軍と政策決定過程 [Japan-US relations during the interwar period: Navy and policy-making process]. 東京: 東京大学出版会, 1993.

—. From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (Annapolis: Naval Institutional Press, 2006), 207.

Friend, Theodore. Indonesian Destinies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003, 21 (From National Library, call no. RSEA 959.803 FRI)

Kenichi, Goto. 後藤乾一. _Kindainihon to Tōnan’ajia ― nanshin no `shōgeki’ to `isan’_近代日本と東南アジア―南進の「衝撃」と「遺産」[Modern Japan and Southeast Asia: “Impact” and “legacy” of Southern Expansion]. 東京: 岩波書店, 2010.

Hatano, Sumio 波多野澄雄. “Kaisen katei ni okeru rikugun” 開戦過程における陸軍 [Army in the process of opening the war]. In Taiheiyō sensō 太平洋戦争 Pacific War, edited by Chihiro Hosoya et al.]. 東京: 東京大学出版会, 1993.

—. “Nipponkaigun to nanshin seisaku no tenkai,” 日本海軍と南進政策の展開 [Japanese navy and the development of the Southern Expansion Policy]. In Sugiyama Shin’ya· ian· buraun-hen. Senkanki Tōnan’ajia no keizai masatsu ― Nihon no nanshin to Ajia· Ō kome 杉山伸也·イアン·ブラウン編. 戦間期東南アジアの経済摩擦―日本の南進とアジア·欧米 [Economic conflicts in Southeast Asia during the interwar period], edited by Shinya Sugimaya and Ian Brown. 東京: 同文館出版, 1994.

Ikeda, Kiyoshi. 池田清, “1930-nendai no tai ei-kan ― nanshin seisaku o chūshin ni” 1930年代の対英観―南進政策を中心に [Japanese view on the UK in the 1930s: A focus on the Southern Expansion Policy]. Aoyama kokusai seikei ronshū dai 青山国際政経論集 [Aoyama International Journal of Politics and Economics] 18 (1990)

Ito, Mikihiko. 伊藤幹彦, Nihon ajia kankei-shi kenkyū ― Nihon no nanshin-saku o chūshin ni 日本アジア関係史研究―日本の南進策を中心に [Research on the history of Japan–Asia relations: A focus on Japan’s southern expansion policy]. 東京: 星雲社, 2005.

Kira, Yoshie and Miyamoto, Masaaki. “Taishō jidai chūki no utsunomiya tarō ― daiyonshidan-chō· Chōsen-gun shirei-kan· gunji sangi-kan jidai” 大正時代中期の宇都宮太郎―第四師団長·朝鮮軍司令官·軍事参議官時代 [Utsunomiya Taro in the middle of the Taisho Period: Assuming Commander of the 4th Division, Commander of Korean Army and Member of the Supreme War Council]. In Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro]. Vol. 3. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

Kitaoka Shinichi 北岡伸一. Nipponrikugun to tairiku seisaku 1906–1918-nen 日本陸軍と大陸政策 1906–1918年 [Japanese army and its policy toward Asian continent 1906–1918]. 東京: 東京大学出版会, 1978.

Kubota, Binji 久保田文次. “Utsunomiya tarō to Chūgoku kakumei o meguru jinmyaku ― magofumi· kōkō· reigenkō· tairiku rōnin· fādorī” 宇都宮太郎と中国革命をめぐる人脈―孫文·黄興·黎元洪· 大陸浪人·ファードリー [Utsunomiya Taro and his personal network surrounding the Chinese Revolution of 1911: Sun Yat Sen, Huang Xing, Li Yuanhong, ronin in China, and Fardouly]. In Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro]. Vol. 2. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

Mimaki, Seiko. “Seiki tenkanki no tsūshō rikkoku-ron ― Meiji-ki nanshin-ron saikō” 世紀転換期の通商立国論―明治期南進論再考 [Development strategy as a trading nation at the turn of the 20th century: Revisiting southern expansion doctrine during the Meiji Period]. 日本思想史学 [Japanese Thought History] no. 38 (September 2006)

Moriyama Yu 森山優. “‘Nanshin-ron’ to `Hokushin-ron’” “南進論”と “北進論” [“Southern Expansion Doctrine” and “Northern Expansion Doctrine”]. In Ajia Taiheiyōsensō 7: Shihai to bōryoku アジア太平洋戦争7: 支配と暴力 [Asia-Pacific War 7: Domination and Violence]. Edited by Aiko Kurasawa et al. 東京:岩波書店, 2006.

Ohata,Atsushiro 大畑篤四郎. Nihon gaikō seisaku no shiteki tenkai 日本外交政策の史的展開 [Historical development of Japanese foreign policy]. 東京: 成文堂, 1983.

Reid, Anthony. The Indonesian National Revolution 1945–1950. Melbourne: Longman, 1974. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.803 REI)

Saito, Seiji 斎藤聖二. “Meiji-ki no utsunomiya tarō ― chūei bukan· rentai-chō· sanbō honbu dainibuchō” 明治期の宇都宮太郎―駐英武官·連隊長·参謀本部第二部長 [Utsunomiya Taro during the Meiji Period: Military Attaché to the UK Embassy, Regimental Commander, and Chief of the Second Division, Department of the Army General Staff]. In Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 1. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

Sakurai, Yoshiki. “Taishō jidai shoki no utsunomiya tarō ― sanbō honbu dainibuchō·-shi danchō jidai” 大正時代初期の宇都宮太郎―参謀本部第二部長·師団長時代 [Utsunomiya Taro in the beginning of the Taisho Era: Assuming Chief of the Second Division, Department of the Army General Staff and Divisional Commander]. In Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 2. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

Shimizu, Gen 清水元, “Senkanki nihon· keizai-teki `nanshin’ no shisō-teki haikei” 戦間期日本·経済的「南進」の思想的背景 [Japan during the interwar period: Ideological background behind economic “southward policy”]. In Sugiyama Shin’ya· ian· buraun-hen. Senkanki Tōnan’ajia no keizai masatsu ― Nihon no nanshin to Ajia· Ō kome 杉山伸也·イアン·ブラウン編. 戦間期東南アジアの経済摩擦―日本の南進とアジア·欧米 [Economic conflicts in Southeast Asia during the interwar period], edited by Shinya Sugimaya and Ian Brown. 東京: 同文館出版, 1994.

Takekoshi, Yosaburo 竹越与三郎. Nangoku-ki 南国記 [Lands of the South]. 東京: 二酉舎, 1910.

The Netherlands Information Bureau. Ten Years of Japanese Burrowing in the Netherlands East Indies. New York: Netherlands Information Bureau, 1942. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 327.12 NET)

Utsunomiya, Taro. 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 1. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

—. 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro]. Vol. 2. 東京: 岩波書店, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS)

Vickers, Adrian. A History of Modern Indonesia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.803 VIC)

Yamada, Akira. Gunbi kakuchō no kindai-shi 軍備拡張の近代史 [Modern history of military expansion]. 東京: 吉川弘文館, 1997.

Yamamoto, Fumihiro. “The Japanese Road to Singapore: Japanese Perceptions of the Singapore Naval Base, 1921–41.” PhD diss., National University of Singapore, 2009.

—. Nichiei kaisen e no michi ― Igirisu no shingapōru senryaku to Nihon no nanshin-ron no shinjitsu 日英開戦への道―イギリスのシンガポール戦略と日本の南進論の真実 [The road to the opening of the Anglo-Japanese War: Britain’s Singapore strategy and the truth of Japan’s southern expansion doctrine]. 東京: 中央公論新社, 2016.

Yano, Nabo. 矢野暢, `Nanshin’ no keifu 南進」の系譜 [Genealogy of “Southern Expansion”]. 東京: 中央公論社, 1975.

—. “Taishō-ki `nanshin-ron’ no tokushitsu” 大正期「南進論」の特質 [The characteristics of “Southern expansion doctrine” in the Taisho period], 東南アジア研究 [Research on Southeast Asia] 16, no. 1 (1978)

Primary Sources

“Kō gō yakubun (Ueda to jì zhi fa no tochi shoyū ken iten keiyaku)” 甲号訳文 (上田と紀芝發の土地所有権移転契約) [Translation of contract A: contract of land ownership transfer between Uyeda and Ki Hiong Tje], 1 November 1910. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428445J)

“Meiji shi jū san-nen jū ichi tsuki shi-nichi ni Koyama aki-saku to Ueda Ushimatsu no ma de musuba reta keiyaku-sho” 明治四十三年十一月四日に小山秋作と上田丑松の間で結ばれた契約書 [Contract agreed between Koyama Shusaku and Uyeda Ushimatsu on 4 November 1910]. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428444I)

Nanpo keiryaku no junbi sagyō ni jiù ki . Meiji 43 toshi 8 tsuki 1 hi . Katajikena chi utsunomiya tarō kashiko hatsu koyama aki saku jinkei otona 南方経略ノ準備作業ニ就キ.明治43年8月1日.辱知宇都宮太郎畏発小山秋作仁兄大人 [On the preparation for the Nanpo Operation, 1 August 1910. From Utsunomiya Taro to Koyama Shusaku], Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428444I)

“Otsu-gō yakubun (Ueda to sarutan· abudaru· rotchimanshiya no tochi baishū keiyaku)” 乙号訳文 (上田とサルタン·アブダル·ロッチマンシヤの土地買収契約) [Translation of contract B: Contract of land purchase between Uyeda and Raja Abdul Rahman Shah], 1 November 1910. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library. (Accession no. B32428445J)

“Sen kyū hyaku jū ni-nen jū tsuki bō Ni~Tsu ni Ueda Ushimatsu ga tan’npinan· Rio-shū fuzoku-chi riji-kan ni okutta chinjō-sho” 千九百十二年十月某日に上田丑松がタンンピナン·リオ州付属地理事官に送った陳情書 [Petition sent by Uyeda Ushimatsu to the Resident of Tanjong Pinang, Riau State in October 1912]. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428445J)

Zai Shin Yoshimi pō Ryōji Dairi Fuku Ryōji Iwatani Jōkichi Gaimu Daijin Kōshaku Komura Kotobuki Tarō Tono 小山秋作の蘭領印度に於て土地租借に関する件. 機密第一号(明治44年1月7日). 在新嘉坡領事代理副領事岩谷譲吉外務大臣侯爵小村寿太郎殿 [Issue regarding Koyama Shusaku’s land lease in the Dutch East Indies. Secret No. 1 (7 Jan 1911). From Iwaya Jokichi, Vice Consul in Singapore, to Marquis Komura Jutaro, Minister of Foreign Affairs], accessed from Japan Center for Asian Historical Records website. (reference code: C03023033600)

NOTES

-

Mikihiko Ito 伊藤幹彦, Nihon ajia kankei-shi kenkyū ― Nihon no nanshin-saku o chūshin ni 日本アジア関係史研究―日本の南進策を中心に [Research on the history of Japan–Asia relations: A focus on Japan’s southern expansion policy] (東京: 星雲社, 2005), 59–68. ↩

-

Sumio Hatano 波多野澄雄, “Nipponkaigun to nanshin seisaku no tenkai,” 日本海軍と南進政策の展開 [Japanese navy and the development of the Southern Expansion Policy] in Sugiyama Shin’ya· ian· buraun-hen. Senkanki Tōnan’ajia no keizai masatsu ― Nihon no nanshin to Ajia· Ō kome 杉山伸也·イアン·ブラウン編. 戦間期東南アジアの経済摩擦―日本の南進とアジア·欧米 [Economic conflicts in Southeast Asia during the interwar period], ed. Shinya Sugimaya and Ian Brown (東京: 同文館出版, 1994), 142. ↩

-

Nobu Yano 矢野暢, `Nanshin’ no keifu 南進」の系譜 [Genealogy of “Southern Expansion”] (東京: 中央公論社, 1975), 147–48. ↩

-

Kiyoshi Ikeda 池田清, “1930-nendai no tai ei-kan ― nanshin seisaku o chūshin ni” 1930年代の対英観―南進政策を中心に [Japanese view on the UK in the 1930s: A focus on the Southern Expansion Policy], Aoyama kokusai seikei ronshū dai 青山国際政経論集 [Aoyama International Journal of Politics and Economics] 18 (1990): 38. ↩

-

Sadao Asada, From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (Annapolis: Naval Institutional Press, 2006), 207. ↩

-

Fumihiro Yamamoto 山本文史, Nichiei kaisen e no michi ― Igirisu no shingapōru senryaku to Nihon no nanshin-ron no shinjitsu 日英開戦への道―イギリスのシンガポール戦略と日本の南進論の真実 [The road to the opening of the Anglo-Japanese War: Britain’s Singapore strategy and the truth of Japan’s southern expansion doctrine] (東京: 中央公論新社, 2016), 161. ↩

-

Ikeda, “1930-nendai no tai ei-kan ― nanshin seisaku o chūshin ni,” 40. ↩

-

Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 1 (東京: 岩波書店, 2007), 331. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS) ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 336–37. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 340. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 351. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 346–47. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 355. ↩

-

Nanpo keiryaku no junbi sagyō ni jiù ki . Meiji 43 toshi 8 tsuki 1 hi . Katajikena chi utsunomiya tarō kashiko hatsu koyama aki saku jinkei otona 南方経略ノ準備作業ニ就キ.明治43年8月1日.辱知宇都宮太郎畏発小山秋作仁兄大人 [On the preparation for the Nanpo Operation, 1 August 1910. From Utsunomiya Taro to Koyama Shusaku], Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428444I) ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 358–59. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 384. ↩

-

The presented 2015 values were calculated according to the consumer price index in urban areas in 1910 and 2015. Meiji - Heisei nedan-shi 明治~平成値段史 [History of prices from the Meiji to Heisei Period] ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 358–59. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 382–84. ↩

-

“Kō gō yakubun (Ueda to jì zhi fa no tochi shoyū ken iten keiyaku)” 甲号訳文 (上田と紀芝發の土地所有権移転契約) [Translation of contract A: contract of land ownership transfer between Uyeda and Ki Hiong Tje], 1 November 1910. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428445J) ↩

-

“Otsu-gō yakubun (Ueda to sarutan· abudaru· rotchimanshiya no tochi baishū keiyaku)” 乙号訳文 (上田とサルタン·アブダル·ロッチマンシヤの土地買収契約) [Translation of contract B: Contract of land purchase between Uyeda and Raja Abdul Rahman Shah], 1 November 1910. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library. (Accession no. B32428445J) ↩

-

甲号訳文. ↩

-

“Sen kyū hyaku jū ni-nen jū tsuki bō Ni~Tsu ni Ueda Ushimatsu ga tan’npinan· Rio-shū fuzoku-chi riji-kan ni okutta chinjō-sho” 千九百十二年十月某日に上田丑松がタンンピナン·リオ州付属地理事官に送った陳情書 [Petition sent by Uyeda Ushimatsu to the Resident of Tanjong Pinang, Riau State in October 1912]. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428445J) ↩

-

乙号訳文. ↩

-

“Meiji shi jū san-nen jū ichi tsuki shi-nichi ni Koyama aki-saku to Ueda Ushimatsu no ma de musuba reta keiyaku-sho” 明治四十三年十一月四日に小山秋作と上田丑松の間で結ばれた契約書 [Contract agreed between Koyama Shusaku and Uyeda Ushimatsu on 4 November 1910]. Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Singapore. (Accession no. B32428444I) ↩

-

Anthony Reid, The Indonesian National Revolution 1945–1950 (Melbourne: Longman, 1974), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.803 REI) ↩

-

Theodore Friend, Indonesian Destinies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 21 (From National Library, call no. RSEA 959.803 FRI); Adrian Vickers, A History of Modern Indonesia (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.803 VIC) ↩

-

Barbara W. Andaya, “From Rum to Tokyo: The Search for Anticolonial Allies by the Rulers of Riau, 1899–1914,” Indonesia 24, no. 24 (October 1977): 136, 148, 152. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Andaya, “From Rum to Tokyo,” 136, 148, 152–54. ↩

-

Koyama aki saku no ran ryō indo ni yú te tochi soshaku ni kansuru kudan . Kimitsu dai ichi gō ( Meiji 44 Toshi 1 Tsuki 7 Hi ) . Zai Shin Yoshimi pō Ryōji Dairi Fuku Ryōji Iwatani Jōkichi Gaimu Daijin Kōshaku Komura Kotobuki Tarō Tono 小山秋作の蘭領印度に於て土地租借に関する件. 機密第一号(明治44年1月7日). 在新嘉坡領事代理副領事岩谷譲吉外務大臣侯爵小村寿太郎殿 [Issue regarding Koyama Shusaku’s land lease in the Dutch East Indies. Secret No. 1 (7 Jan 1911). From Iwaya Jokichi, Vice Consul in Singapore, to Marquis Komura Jutaro, Minister of Foreign Affairs], accessed from Japan Center for Asian Historical Records website. (reference code: C03023033600). ↩

-

Andaya, “From Rum to Tokyo,” 148–49. ↩

-

Andaya, “From Rum to Tokyo,” 148–49. ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 412–14. ↩

-

Anda , “From Rum to Tokyo,” 146–47. ↩

-

Gen Shimizu 清水元, _Senkanki nihon· keizai-teki `nanshin’ no shisō-teki haikei_戦間期日本·経済的「南進」の思想的背景 [Japan during the interwar period: Ideological background behind economic “southward policy”] in Sugiyama Shin’ya· ian· buraun-hen. Senkanki Tōnan’ajia no keizai masatsu ― Nihon no nanshin to Ajia· Ō kome 杉山伸也·イアン·ブラウン編. 戦間期東南アジアの経済摩擦―日本の南進とアジア·欧米 [Economic conflicts in Southeast Asia during the interwar period], ed. Shinya Sugimaya and Ian Brown (東京: 同文館出版, 1994), 19–20. ↩

-

Shimizu, Senkanki nihon· keizai-teki `nanshin’ no shisō-teki haikei, 75. ↩

-

Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 2. (東京: 岩波書店, 2007), 147. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS) ↩

-

Seiji Saito 斎藤聖二, “Meiji-ki no utsunomiya tarō ― chūei bukan· rentai-chō· sanbō honbu dainibuchō” 明治期の宇都宮太郎―駐英武官·連隊長·参謀本部第二部長 [Utsunomiya Taro during the Meiji Period: Military Attaché to the UK Embassy, Regimental Commander, and Chief of the Second Division, Department of the Army General Staff] in Taro Utsunomiya 宇都宮太郎, Nipponrikugun to Ajia seisaku: Rikugun taishō utsunomiya tarō nikki 日本陸軍とアジア政策:陸軍大将宇都宮太郎日記 [Japanese army and Asia policy: Diary of Army General Utsunomiya Taro], vol. 1. (東京: 岩波書店, 2007), 45. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 952.03092 UTS) ↩

-

Utsunomiya, Nipponrikugun to ajia seisaku, vol. 1, 129–30. ↩

-

Shimizu, 19–20. ↩