Exploring Accounts of the Lifestyles of Colonial Administrators and Their Families in Singapore

Introduction

In 1900, British traveller and sometime political activist Ethel Colquhoun visited Singapore during a tour of the Pacific with her husband, an imperial administrator and explorer. During a stay of several days, she recorded her views on the landscape and society that she observed. One of the most striking and critical passages of her account deals with Singapore’s European residents:

They live in the baleful atmosphere of a hothouse. They are exiles

and prisoners on a cramped little island, from which they cannot

even escape for a short holiday at times, only to go “home”. They

naturally get to regard Singapore as the hub of the universe, and

to feel as if the whole creation centred round their tiny world of

small civil, military and mercantile duties. They can’t exercise

charity to their poorer neighbours – for neither Chinese nor Malays

are exactly subjects for my Lady Bountiful – so that it is not

perhaps wonderful that that much-abused virtue gets rusty in their

intercourse with social equals.1

Throughout the period 1870–1920, during which Singapore was administered as part of the Crown Colony of the Straits Settlements within the British Empire, visitors and residents were keen to record their thoughts on the island’s European community. While some accounts were written by travellers passing through, others recorded the experiences of men and women who had spent longer periods living and working in British Malaya.

Colquhoun’s comments reflect several key themes that appear throughout many contemporary accounts. Discussions of the nature of society are rooted in ideas of separation and isolation, the relationship with Britain as “home”, and interactions between racial and occupational groups. While many accounts follow Colquhoun’s lead and criticise the way of life they observe among the European population, others present a more favourable view, highlighting the perceived benefits of a tropical lifestyle, the strengths of the small European community in Singapore and what they believed were improvements to the outlook and living conditions of Chinese, Malays and Indians as a result of “the presence of English law and…the protection of the British flag”.2 While an individual’s views are to an extent attributable to personal experience, position and perspective, there are wider themes and ideas relating to the ideologies that structured late 19th- and early 20th-century colonial society, which are important to consider when exploring these accounts and the views their authors express.

Source Material

The Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and the National Archives of Singapore hold an array of English-language material recounting the experiences and attitudes of British colonial administrators and their families during time spent in Singapore, and the Straits Settlements and British Malaya more widely. The material held in Singapore institutions takes a variety of forms, from published travellers’ accounts and semiautobiographical prose produced by members of the island’s European community, to original and facsimile copies of letters and diaries. Newspapers and magazines – ranging from broadsheets such as The Straits Times to the satirical Straits Produce – record the activities and concerns of Europeans who lived on the island and their relationship to wider regional and international affairs, while official records including census data, the Civil Service List and the Blue Book further outline the structure and boundaries placed upon the administrative community.3These texts provide a valuable supplement to existing work on the peopling of the British Empire and the creation of settler communities and identities, much of which focuses on British India, and is interested in governors at the top of the imperial hierarchy, or relies upon official documents held in archives in the United Kingdom.

The Colonial Administration in Singapore c. 1870–1920

It is an article of popular belief that Englishmen are born sailors;

probably it would be more true to say that they are born administrators.

– Frank Swettenham, 19074

British colonial administrators and their families were one small yet significant part of the European population that resided Singapore in the 19th and 20th centuries and were frequently the subject of accounts by residents and visitors. The 1881 census indicates 2,769 European men, women and children as residents in Singapore, of whom 862 were described as “British”. By 1910, the number of British inhabitants had increased to 1,870. However, in a total population of over 228,000, this category still represented less than one percent.

Within this category, an even smaller number made up the “administrative class”, those who were employed as civil servants within government departments. The 1881 Straits Settlement Census gives a figure of 84 Europeans and Americans serving in the civil service in Singapore, out of a total population of 139,208.5

While it remained common for those in the upper ranks of the administration to enter from roles elsewhere in the British Empire, the armyor, less commonly, the home administration, a professional colonial civil service ethos and local identity developed within Malaya in the aftermath of the establishment of the Straits Settlements as a Crown Colony in 1867. Young cadets were recruited through an increasingly formalised system of examination. The nature of this appointment system and the general esprit de corps that permeated the colonial civil service meant that many of the men fit a similar profile, having been raised in the British middle class and educated in British public schools and leading universities.6

In 1904, the introduction of a colour bar restricted recruitment to the Malayan Civil Service to those of “pure European descent”, although the number of non-whites who had held positions in the civil service or commissioned roles in the police before that date had always been small.7

While women were not appointed to positions within the colonial administration during this period, the white female presence in Singapore grew slowly both as a result of an increasing number of nurses and teachers sent into the imperial sphere, and an acknowledgement that it was acceptable and indeed desirable for wives to accompany their administrator husbands to the Empire.8 Although they continued to be outnumbered considerably by men, there were 1,620 white women recorded in Singapore in the 1911 census, in contrast to 495 European and American women and girls recorded in 1881.9

Although a small population, the nature of imperial power vested these women with significance and the ability to shape society. While valuable work has been done to highlight the voices of other groups in colonial Singapore who have historically been silenced,10 the archival footprint of the men, women and children whose presence in Singapore was tied to the administration of the imperial state allows their lives to be subject to continued analysis.

Imperial Careering

The concept of “imperial careering” is a useful analytical framework that can be used to explore the time administrators spent in Singapore and how their occupations shaped the way they saw their lives there. It highlights how individuals’ lives and careers were influenced by their movement within and across imperial space, and how these movements formed part of the interwoven networks and stories that invested these spaces and the people who occupied them with specific identities.11

Framing lifestyles with reference to careers is particularly relevant to colonial Singapore due to the belief expressed in contemporary sources that no man should move to the island without a job, both for their own sake and to preserve the prestige of the wider white community.12 For new arrivals, colleagues replaced the networks of friends and family they had left behind in the United Kingdom or elsewhere. The close link between occupation and European presence in Singapore is underscored by the fact that it was rare for administrators to remain in Malaya after their careers had ended, even if they had spent the bulk of their lives there. In 1881, the total number of British residents over the age of 60 in Singapore was no more than 22.13

The Straits Settlements Civil Service List, produced annually from the 1880s, presents the names, educational backgrounds and career paths of every individual who joined the administrative service, from newly recruited cadets to the governor. These texts enabled residents and visitors to gain an understanding of the individuals who made up administrative society and to relate themselves into the hierarchy outlined.14 They can also be used to track the experiences that created individuals’ imperial careers and cross-referenced with other sources, such as newspapers or private correspondence.

Lives Within and Across Imperial Space

Two case studies highlight how the source material can be used to reconstruct the role that Singapore played within an individual’s career and allow us to attempt to reconstruct how this may have impacted the sense of place and the networks in which they were situated.

Frank Kershaw Wilson came to Singapore in 1914 as an administrative cadet. From January 1915 to December 1916, he wrote regularly to his parents in the United Kingdom – copies of these letters are held as microfilm in the collection of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, Singapore.15 Cross-referencing these letters with Kershaw Wilson’s career recorded in the annual Civil Service List creates a picture of his career and the part that Singapore played within this. Over a period of more than 25 years in British Malaya, he was posted to eight different locations, spanning the Straits Settlements and the Federated and Unfederated Malay States with no clear regional “base” to which he returned over the course of his career.

In his letters, Kershaw Wilson appears to view his time and early career in Singapore with a sense of frustration. He expresses eagerness for the day that he is relocated upcountry and given the increased workload and responsibility that he yearns for, and laments the costs associated with maintaining the lifestyle required to participate within Singapore’s particular urban society.16

Mapping his career also highlights that alongside his conception of himself within a broader Malayan imperial space, his career is firmly rooted in relation to Britain as “home”. Though his visits to the United Kingdom were infrequent, they were associated with significant events such as promotions, relocations and even his marriage in the late 1920s, as well as being the site of his eventual retirement. It is possible thus to view his career in Malaya as developing within a specific local context framed by movement and the development of particular skills and knowledge, but also mediated by this continued relationship with and dependence on networks of connection to the United Kingdom.

A comparable example of a life spent within imperial space can be seen in an examination of the career of Walter Cecil Michell, who was recruited as a cadet in the Straits Settlements Civil Service in 1887, after completing his undergraduate degree at the University of Oxford. Michell was based in Malaya until his retirement in 1919. His obituary, published in Singapore newspapers in 1939, provides several interesting elements that can be related to considerations of his life and career.17 As with Kershaw Wilson, Michell was posted to a range of locations within Malaya during his career, spending only a short period in Singapore. Despite this, and the fact that he had retired from the Malayan administration two decades earlier, his death was reported in the Singapore press, suggesting he remained part of the community there in some way, despite a gap across space and time. Indeed, that Michell and his wife were living in the south of France when he died rather than in the British metropole acts as a reminder that not all networks tied an individual back to the country that they had originally come from.

The next generation of the Michell family also continued to operate within multiple networks across space and community. Michell’s daughter Stella, who was born in Singapore in 1902, features in a two-page spread in the 1907–8 edition of The Straits Times Annual, which showcased the offspring of some of Singapore’s European residents under the heading “Children of the Empire”. By the age of eight, Stella had been sent back to Britain for schooling and never again lived in Singapore.18 Despite this, however, her identity remained tied to the place she was born and the imperial project that her family contributed to. Several episodes in her life, including her 1937 marriage in France and subsequent commitment to public service as the wife of a colonel in the British army, were reported in the Singapore press. Stella remained a child of this imperial community despite her family’s residence in Singapore having ceased several decades earlier.19

The mobility associated with an imperial career outlined in the above examples appears at odds with Colquhoun’s view of Europeans in Singapore as existing within “a cramped little island”. However, this is an idea that prevails in several accounts of both residents and visitors. The lethargy often presented as a defining feature of life for white inhabitants is frequently linked to references to the position of these men and women far from their friends and families, struggling against the climate and lacking intellectual pursuits.20 An obsession with the coming and going of the mail is a motif often evoked to demonstrate the dependence upon any interaction with the wider world to infuse the community with vitality.21 A contrast thus appears to exist between the long-term, career-spanning movement and networks, and shorter-term feelings of isolation and stagnation.

Studying the sources highlights the existence of networks within and across imperial space that were more complex than simply ties linking points on the periphery back to the metropole and invested Singapore with a particular regional as well as global identity. An 1898 description of Singapore as the “capital of a little Empire” has implications for how we can understand Singapore within a system that did not require constant links to the metropole for its identity and place in the world.22 While there were significant differences between the institutions and norms that governed life in Malaya’s urban centres and the rural upcountry, the nature of imperial careering as presented earlier ensured that it was unheard of for an administrator to spend the entirety of his life in Malaya within one of these social formations.23 The ways that individuals related to Singapore specifically and as part of a wider British Malayan space were often complex and contradictory, illustrating the idea that there were multiple identities and imagined communities that could be drawn upon at particular times.24

It has already been mentioned that Kershaw Wilson perceived his time in Singapore as a precursor to his career proper in upcountry Malaya, while when reflecting back on his time in Malaya, former planter Robert Bruce Lockhart stated that “to me, Singapore has never been more than an exotic island. I was an FMS man”.25 However, for others, Singapore functioned as an important reference point and mediatory that anchored their lives and careers. Emily Innes, the wife of a colonial administrator who spent time in Malaya during the 1870s and 80s, took joy in the opportunities presented to her to escape the isolation of her life with trips to vibrant, busy Singapore.26 Similarly, three decades later, Margaret Birch escaped from her life in Perak to visit Singapore to shop, visit friends and attend social events such as balls and the races.27 Singapore was often the place where administrators first landed to take up posts elsewhere in British Malaya, greeted by recognisable institutions under the protection of the Union Jack; it may have been a place where men and women were sent to temporarily recuperate or prepare to leave the tropics for health reasons; it was frequently the site of significant life events such as marriages and births; and it was where British administrators and their wives were sent for dealings with senior judicial or administrative powers.28

For those who spent longer periods residing in Singapore, improved communications over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries ensured that at times, the settlement felt more like a British town than an island thousands of miles from London.29 It was possible to receive weekly letters and business papers from home even in the midst of the disruption of the First World War, while advice given in guidebooks aimed at British men and women relocating to tropical parts of the Empire stress that it was possible, and indeed important, to keep up with the latest British fashions and styles.30 Not only letters, but goods and people were constantly sent across the world, connecting Singapore to elsewhere in Malaya, the United Kingdom and beyond. The fact that many of the middle-class travellers, whose accounts are preserved in the collections of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, were able to call on and interact with existing friends, families and social networks upon their arrival in Singapore highlights how the feelings both of isolation and connection to “home” were frequently tested and reinforced by ongoing patterns of movement.31

A Structured and Controlled Social World

The “tiny world” of European society in Singapore created a particular social milieu which was frequently commented upon in the writings of those who observed or participated within it. In his account of an 1899 visit to Singapore, Walter del Mar laid out some of the tensions that existed within such a society:

In small communities of Europeans, settled in the midst of

another race with which there is practically no social intercourse,

the individuals become closely united by ties of friendship and

intimacy as well as by interest and for mutual protection…[they]

assume with little friction the rank in the social scale to which they

are entitled…everybody is “somebody” down to the club inebriate

who is drinking himself to death….32

The club acted as a key institution for socialisation, and the interactions between colonial residents and visitors were structured with reference to sport, amateur dramatics, the custom of calling cards and formal dinners in the homes of administrators and commercial tuan besar. Recreation and leisure time followed specific, prescribed forms and played an important part in both demonstrating the status of white residents through their competitive mindsets and physical prowess, and in building bonds and creating familiar environments in which new arrivals could easily find their place.33 Writing in 1878, William Temple Hornaday described Singapore as “like a big desk, full of drawers and pigeon holes, where everything has its place and you can always be found in it”, encapsulating a sense of both the structured nature of interactions, and the central role that work played in defining these relations.34

The source material also conveys an awareness of how the fluidity and transience of the lives and careers of many members of colonial society impacted the community’s social and intellectual vitality. At various points over the 50-year period from the 1870s to the 1920s, visitors and residents reflected upon the changes they observed in both the physical layout of Singapore, and the social norms and practices that governed society, often nostalgically evoking a friendlier, less formal past and lamenting the loss of particular practices and individuals.35 One Hundred Years of Singapore, published to mark the centenary of Raffles’ landing on the island, regretfully records the demise of cycling and debating societies, and short-lived journals covering topics such as athletics and motor cars.36 The short-lived and transitory nature of many initiatives in Singapore impacted the community memory of Singapore’s European society. When the satirical Straits Produce magazine was revived in 1922 after a 24-year hiatus, the editors stressed that “there are very few in Singapore to-day who remember the Nineties nor are there many sufficiently versed in its past history to understand the topics”

that appeared in earlier issues.37 A similar impression is given by Thomas Keaughran, writing in The Straits Times in 1887. He laments the lack of care paid to the Christian cemetery at Bukit Timah, stating:

Perhaps the mobile nature of our European population may in

some measure account for this, as there are few connecting links

of attachment reposing here to endear them to the spot. Still, the

same apparent disregard seems to pervade the permanently resident

inhabitants, many of whose progenitors here repose; even them

youth…here shun the locality.38

“Singapore Is for the Singaporean: To Him Only It Has Its Attraction.”39

Despite the mobile population, however, some sources demonstrate how, at particular moments and for particular individuals, Singapore and an identity as “British Malayans” or even “Singaporeans” came to possess a significance and relevance not only for the men who worked as administrators, but for their wives and children. Practical and ideological shifts meant that it became increasingly common for men to marry and start families during the time they were employed as administrators in British Malaya, impacting both the nature of the society that existed in Singapore and the relationship between colonial outpost and British metropole.40

The wives of administrators loom large in primary accounts and secondary literature, often framed as the ignorant mem, transplanted to an alien land, struggling with climate and disease, her presence ultimately responsible for the deterioration of relations between white men and the races they governed, and the eventual decline of the British Empire.41 However, to view the lifestyles of colonial wives solely in this way would be to neglect both the active role many women played in shaping their own lives and that of their families, and the ideological role that they played in the construction of the colonial project.

In her work on British India, Mary Procida argues that as members of the official community, colonial wives had a material, psychological and ideological stake in the continued success of the British Empire.42 Seizing upon their “incorporated” status, they were able to draw on their positions within the hierarchy of imperial administration to place a significance upon their lifestyles that did not exist for their counterparts “at home”. Procida’s work highlights the way that the sharp divide between public and private spheres existing in British homes did not translate to the imperial context, with even so-called “private” and traditionally feminine domestic spaces required to serve the demands of empire.43 Wives of governors were required to set an example for wives lower down the hierarchy through their behaviour and hospitality. Even those married to more junior administrators were expected to participate in the management of household tasks and servants to reinforce the authority of the colonising power, and sustain structured habits of socialisation that were intrinsic to the success of their husbands within the hierarchy of the imperial civil service and in turn the British Empire at the broader level.44

Writing to his fiancée Kips in England in 1916, Richard Myrddin Williams, a junior employee of commercial firm Paterson and Simons, outlines the particular significance given to women in maintaining a household and entertaining their husbands’ colleagues, both tasks which held an important role in structuring relations with other races and the development of business relationships. Over a series of letters, he prepares her for the responsibilities associated with these tasks, explaining how, although she might find it overwhelming, running a household was a particularly important role held by women in Singapore.45 Within the administrative sphere, a similar picture is presented by the diaries of Margaret Birch. Birch, who followed her husband to a range of localities within Malaya including Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Borneo, describes her busy life, which required her to take on roles including overseeing the work of prisoners employed as domestic staff, entertaining visitors and dinner guests, and travelling within and beyond Malaya independently of her husband.46

Written testimonies by women demonstrate that within Malaya, for some women at least, it was possible both to actively participate in the networks and processes of their husbands’ imperial careers, and to conceptualise and construct how the process of colonialism was structured and implemented. Dorothy Cator drew on her own experiences of life in Borneo to address an assembled crowd at the Royal Colonial Institute in London in 1909. In her speech, she expressed her opinions on a range of aspects of British colonialism, from commenting on the way that those in Britain perceived of “our Colonies”, to making suggestions relating to the education of colonial administrators.47 Several decades earlier, Emily Innes had spent time living with her husband as he served in the colonial administration of the Malay States. Her The Chersonese with the Gilding Off, published in 1885, provides an example of a woman championing her husband and his career in the face of perceived injustices, criticising both the nature of the system of imperial administration and the life that it forced her and her husband to live.48

Children, too, could be vested with a role within the process of imperialism that gave them and their lives a significance to both Singapore’s European community and the colonial government. As in the case of Stella Michell, the white sons and daughters of British administrators could be celebrated as “children of empire” and their activities were often recorded in the Singapore press long after they and their parents had permanently relocated elsewhere. However, it was a frequently expressed view that it was unsuitable for these children to remain in a tropical climate beyond the age of six or seven.49 The impact that this had on the demographics of Singapore is

illustrated by census data from 1881, which demonstrates that there were more than double the number of two- and three-year-olds as 13- and 14-year-olds among the British population.50 The presence of children in colonial contexts was closely tied to both ideologies of Empire rooted in pseudo-scientific notions of racial superiority and the dangers of hostile climates upon white bodies, and shifts in how childhood was perceived within society in late 19th- and early 20th-century Britain, with an increasing state interest in processes of child rearing.51

In his semi-autobiographical short story Rachel, Hugh Clifford focuses on the impact that the practice of sending children back to Britain at a young age had on both children and adults. The future governor of the Straits Settlements highlights how administrators and their wives were forced to decide between their role as parents responsible for raising the next generation of national and imperial citizens, and their position as imperial servants.52 The decision to send children home to attend British public schools acted to reinforce a particular middle-class ethos, and to frame their fragility with reference to claims for racial authority and hierarchy rooted in nature and biology.53

Children who were educated in Singapore or unable to return to the United Kingdom at the expected time were limited in the positions they could hold within the administrative hierarchy. A 19th-century example of such a scenario is found in Dill Ross’ semi-autobiographical publication Sixty Years: Life and Adventure in the Far East. The author recounts the fate of a son of a penniless skipper. Financial troubles meant that he had to remain in Singapore for school, where the author states he received a poor standard of education “amidst half-castes and native boys”. Upon graduation he sought employment in the government service, but was unable to advance beyond clerk level due to the “odium of being what is called a ‘country’ born”. It was only when he moved to employment in the commercial sector that he was able to flourish, drawing on his specific local knowledge and behaviour to the advantage of his career.54 Decades later, writing under the name Clive Dalton, Frederick Clark explains in his account of his childhood on Pulau Brani that as a result of his family’s prolonged stay on the island due to the First World War, his education was irreversibly disrupted and he was thus unable to attend Sandhurst and pursue the career expected of him.55

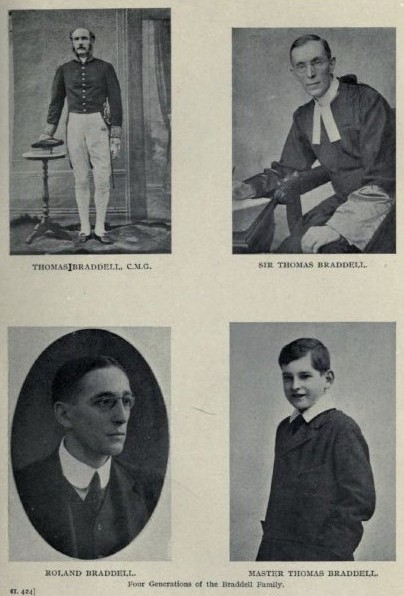

After visiting Singapore in 1879, Andrew Carnegie stated that permanent occupation of the island by Western races is “of course out of the question. An Englishman would cease to be an Englishman in a few, a very few generations”.56 However, in the 1921 centenary publication One Hundred Years of Singapore, the author proudly boasts of the longevity of several Singapore “dynasties”, including familiar names such as Braddell and Maxwell.57 The work lists the achievements of particular individuals in creating a flourishing European colonial society, proudly recounting the long-term associations between generations of these “Empire Families” and the development of Singapore and its institutions, acknowledging the exceptional nature of their commitment to the island and the status that this gave them.58

The year 1882 saw the marriage of Ernest Woodford Birch and Margaret Niven, representing the union of two individuals and families with personal histories rooted in a specifically Malayan context – Birch was a member of the Straits Settlements Civil Service and the son of J. W. W. Birch, the British Resident of Perak assassinated in 1875, while the aforementioned Margaret was the daughter of Lawrence Niven, the proprietor of a nutmeg plantation and later manager of the Botanic Gardens.59 Similarly, a year later, Edward Merewether, a Straits Settlement cadet and son of a member of the Indian Civil Service, married the daughter of Thomas Braddell, Singapore’s first Attorney-General, at St Andrew’s Cathedral in a wedding attended by leading members of European society.60 Despite moving to Malta and Sierra Leone later in life, the activities and affairs of the couple – including visits to the Association of British Malaya in London – continued to be reported in the Singapore press.61

What is clear, however, is that the Singaporean identity claimed by long-term white residents in One Hundred Years of Singapore was ideologically separate and distinct from a wider notion of shared nationhood and

citizenship. Instead, it related to identification with a specific “imagined community” based on occupation, race and nationality and a self-assurance that they would be free to be welcomed back into British society at the end of their careers. By sending children back to Britain for education, they were able to access domestic middle-class identities and undertake professional occupations and maintain the “English” identity that Carnegie feared would be lost. It was by no means certain that the sons of administrators would follow in their fathers’ footsteps and pursue a career in the Malayan administration. Members of the dynasties outlined in One Hundred Years of Singapore were not confined to the administrative sphere or to Singapore, with many pursuing commercial activities or moving elsewhere in the Empire.62

The impression given by the sources is that the particular “Singaporean” society celebrated in the centenary publication was predominantly white, with only a few Chinese or Malays with whom it was deemed acceptable to interact. A visit to the garden of leading Chinese businessman Whampoa Hoo Ah Kay featured on the itinerary of any well-informed visitor to Singapore, while dinner with the Sultan of Johor was not uncommon for travellers passing through Singapore as well as those residing there for longer periods.63 Based on a visit to Singapore in 1905, George Morant stated that “as a rule, the European residents took little or no interest in the manners and customs of the native inhabitants”,64 and those who developed close personal relations with members of other races, particularly Eurasians, saw their position in Singapore suffer.65

Interactions with non-European residents were clearly structured and regulated. Cadets often engaged closely with Malays as teachers, rooted in the belief that a successful administrator needed to acquire a knowledge of the language and culture of the native inhabitants of the country he was to govern, while it was possible to interact with English-educated Chinese as part of the imperial system of divide and rule.66 Despite rhetorical justifications of Empire rooted in references to late Victorian liberalism, a “civilising mission” and a perception of the inherent suitability of the British to rule as a result of their benevolence and justice, philanthropic activities appear to have fallen outside the remit of administrators, being left to missionaries, professionals such as doctors or teachers from outside the administrative hierarchy, or wealthy members of other races.67 A 1917 article in the Malaya Tribune claimed Singapore possessed the poorest standard of education among the British Crown Colonies, attributing it to the fact that:

the European population here is a floating one. Nine out of ten

have not the slightest intention of making this their permanent

home, with the result that there is not very much interest

evinced in a question which is of the greatest importance to the

permanent population.68

While it was therefore possible for those who lived in Singapore to perceive themselves and others as holding a family or individual identity rooted in their particular local context, it is important to remember that when required, administrators were able to draw upon a coexisting set of identities and connections that bound them to Britain and marked them out from the bulk of the island’s population.

Conclusion

Exploring the rich body of evidence documenting the lifestyles of colonial administrators and their families is valuable in reinforcing the idea that colonialism and the British imperial project should best be understood not as an abstract, inevitable force of history, but a collection of actions carried out by individuals and the consequences that these actions had and continue to have upon society.

Colquhoun’s critique highlights some of the key tensions witnessed and experienced by white British, American and European visitors and residents in Singapore, but fails to reflect the variations in experience that appear to have been influenced by a range of factors, the nuances of which are fundamental in any attempt to understand the complexities and contradictions involved in the implementation of the British imperial project. Singapore in the 19th century was complex and diverse, with individuals and communities isolated and connected in multiple ways, possessing identities that could be selectively drawn upon in different contexts. Robert Bickers encapsulates these multiplicities with reference to European communities within the imperial diaspora when he states that “the overseas Briton was a Rhodesian, or a Shanghailander, but she was also a colonial, a ‘citizen of the empire’…set aside from the British mainstream by self-perception and the perception of home Britons”.69

While on the one hand the record of these variations are shaped by individual experiences – such as how long the author of an account spent in Singapore, their position within the administrative hierarchy and their family backgrounds – they should also be framed within a wider ideological context of imperialism and the conflicts implicit in the way that colonial power was implemented. Those interacting with society from a European or American viewpoint were observing norms that had been adapted and reworked to fit an imperial purpose and support an ideology of rule. From the way that women were both invested with important roles as “the mothers of empire” and yet separated from their children as they grew up, to the framing of privileged white men who chose to pursue careers in the Empire as “exiles”, the construction of identities and ideologies within the context of Empire was complex and often contradictory. Highlighting these tensions and multiplicities allows us to better understand how we should situate colonial administrators in Singapore both within their local and regional contexts, as well as within the broader British imperial system.

Further study of the ideas, topics and issues touched upon in this work will be valuable for continuing to develop our understanding of colonial Singapore. Archives are not neutral repositories of information, and it is important to acknowledge that the materials that are available for consultation represent but a small part of the total body of information, reflecting prevailing ideologies and power structures. An analysis of non-English language sources or a focus on those who interacted with white administrators in roles as clerks or even cadets pre-1900 would add an important dimension to understanding how administrators were perceived and the wider social context in which they were situated. Focused individual case studies of careers and lives spent within a specifically Malayan context would be valuable should source material that makes such a detailed analysis possible be found. There is also scope for an analysis which focuses in greater detail on both the divergences and similarities between Singapore and the other localities in British Malaya. Overall, therefore, the collections held by NLB and NAS present a valuable source through which the lifestyles of administrators can be considered, and provide the tools that can be used to go beyond accounts of colonial pioneers and governors to interrogate existing stereotypes and perceptions, and the ideologies and power structures through which they were historically created and upheld.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Dr Donna Brunero for her comments and guidance during the duration of my Fellowship, and the staff at NLB and NAS, particularly Joanna Tan, for their recommendations and help with accessing materials. Thanks also to Hubert for all his advice relating to Singapore and its history. This work would not have been possible without their support.

REFERENCES

Primary Sources - Published Materials

Applin, R. V. K. Across the Seven Seas. London: Chapman & Hall, 1937. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 355.00924 APP-[RFL])

Bastin, John, ed. Travellers’ Singapore: An Anthology. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5705 TRA-[JSB])

Bird, Isabella. The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither. London: John Murray, 1883. 111 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 BIS; microfilm NL 5876)

Brassey, Annie. A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months. 3rd ed. London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1878. (From National Library Online)

Brown, A. Edwin. Indiscreet Memories: 1901 Singapore Through the Eyes of a Colonial Englishman. London: Kelly & Walsh, 1935. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 BRO; microfilm NL16352)

Lockhart, Bruce, R. H. Return to Malaya. New York: Putnam, 1936. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 LOC-[JSB]; microfilm NL18264)

Caddy, Florence. To Siam and Malaya in the Duke of Sutherland’s yacht, “Sans Peur”. London: Hurst and Brackett, 1889. (From National Library Online)

Cameron, John. Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India: Being a Descriptive Account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wellesley and Malacca: Their Peoples, Products, Commerce and Government. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1865. (From National Library Online)

Carnegie, Andrew. Round the World. New York: [s.n.], 1957.

Clifford, Hugh. Hugh Clifford, “Rachel,” Living Age 239 (1903): 468–535.

Colquhoun, Ethel. Two on Their Travels. London: W. Heinemann, 1902. (Call no. RRARE 910.4 COL; microfilm NL25803)

Dalton, Clive. A Child in the Sun. London: Eldon, 1937. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 DAL-[JSB]; microfilm NL18263)

Del Mar, Walter. Around the World Through Japan. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1904. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.41 DEL-[JSB])

Dill Ross, John. The Capital of a Little Empire: Descriptive Study of British Crown Colony in the Far East. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, 1898. (From National Library Online; microfilm NL 5829)

—. Sixty Years: Life and Adventure in the Far East, vol. 1. London: Hutchinson, 1911. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959 ROS; microfilm NL14209)

Farlow, Minnie. Singapore Skits in Prose and Verse. Singapore: Singapore and Straits Print. Off., 1896. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 820 MF; microfilm NL5827)

Gilmour, Andrew. An Eastern Cadet’s Anecdotage. Singapore: University Education Press, 1874. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 920 GIL)

Hornaday, William T. Two Years in the Jungle: The Experience of a Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo With Maps and Illustrations. London: K. Paul, Trench, 1885. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.043 HOR; microfilm NL7981)

Innes, Emily. The Chersonese With the Gilding Off. London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1885. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 915.951043 INN)

Keaughran, T. J. Picturesque and Busy Singapore. Singapore: Lat Pau Press, 1887. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.951 KEA; microfilm no. NL5829)

Kratoska, Paul, ed. Honourable Intentions: Talks on the British Empire in South-East Asia Delivered at the Royal Colonial Institute 1874–1924. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1983. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 HON)

Leigh Hunt, Shirley and Alexander S. Kenny. Tropical Trials: A Handbook for Women in the Tropics. London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1883.

Makepeace, Walter, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell. One Hundred Years of Singapore: Being Some Account of the Capital of the Straits Settlements From Its Foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919. Vol. 1–2. 2016. Reprint. London: John & Murray, 1921. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]

Malayan Civil Service. The Malayan Civil List. Singapore: Printed at the G.P.O., 1939. (From National Library Singapore, RRARE 354.595002 MCL; microfilm NL9784)

Morant, Geo C. Odds and Ends of Foreign Travel. London: Charles and Edward Layton, 1913. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 901.4 MOR)

Norman, Henry. The Peoples and Politics of the Far East: Travels and Studies in the British, French, Spanish and Portuguese Colonies, Siberia, China, Japan, Korea, Siam and Malaya. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1895. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 950 NOR-[KSC]; microfilm NL25995)

Rennie, J. S. M. Musings of J.S.M.R., Mostly Malayan. Singapore: Malaya Pub. House, 1933. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 REN; microfilm NL8447)

Sidney, Richard J. H. In British Malaya To-Day. London: Hutchinson & Co., 1927. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SID-[RFL])

Straits Produce 1, no. 3 (1893)–v. 12, no. 3 (1934). From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51033 SP

Straits Settlements, Blue Book for the Year. Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1881. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB; microfilm NL2896)

—. The Straits Settlements Civil Service List Showing The Civil Establishments, Names and Designations of the Civil Servants of Government. Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1884. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RARE 351.2 STR; microfilm NL5821)

—. The Straits Settlements Civil Service List Showing The Civil Establishments, Names and Designations of the Civil Servants of Government. Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1902. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RARE 351.2 STR; microfilm NL5821)

—. Blue Book for the Year. Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1911. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB; microfilm NL2896)

Swettenham, Frank A. British Malaya: An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya. Rev. ed. London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1948. (From National Library Singapore call no. RSING 959.5 SWE)

The Straits Times, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States Annual. Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1908. (From National Library Singapore, microfilm NL5876)

Newspaper Articles (From NewspaperSG)

Malaya Tribune. “Malayans at Home.” 27 March 1937, 13.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “News in Brief.” 21 March 1939, 3.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly). “The Health of the Governor.” 29 August 1893, 6.

Straits Times. Sylvia, “The Little Things of Life.” 13 July 1906, 8.

—. “Children in Singapore.” 11 June 1914, 10.

—. “Social and Personal.” 25 June 1927, 8.

—. “Sir Ernest Birch: Biographical Sketch of Noted Administrator.” 17 January 1930, 4.

Straits Times Weekly Issue. “Topics of the Day.” 29 January 1883, 4.

—. Keaughran, T. J. “Picturesque and Busy Singapore.” 17 January 1887, 6.

Personal Correspondence and Archival Material

Birch M. “Papers of Sir Ernest Birch (Box 1 of 12): Personal Diaries of Mrs Margaret Birch, 1896–1904, With a Loose Programme of Amateur Theatricals at the Tanglin Club, 1885.” Box 1, private records, 187619–29. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. MSS.Ind.Ocn.s.354; microfilm NAB 0803)

Kempe, Erskine John. John Erskine Kempe, Diaries, vol. 1–10, December 1911 to 1934. MSS.Ind.Ocn.S.94. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1986. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.503 KEM; microfilm copy held in NLB)

Kershaw, Wilson Frank. Frank Kershaw Wilson’s Letters Home, January 1915 – December 1916, While As Administrative Cadet, Singapore. MSS. Ind.Ocn.S.162. Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. Singapore: National Library Board, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5703 WIL; microfilm copy held in NLB)

Williams, Richard Myrddin. Richard Myrddin Williams: Letters to Katherine Paterson, 1913–1918. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5703 WIL)

The National Archives (United Kingdom). Singapore: Investigation of Mrs Acton, Wife of Roger Acton of the Straits Settlements Civil Service, private records, 01/01/1916-31/12/1917. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. FCO 141/16032)

Secondary Material

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 320.54 AND)

Beuttner, Elizabeth. Empire Families: Britons and Late imperial India. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bickers, Robert. Settlers and Expatriates: Britons Over the Seas. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 305.341 SET)

Brownfoot, N. Janice. “Sisters Under the Skin: Imperialism and the Emancipation of Women in Malaya c. 1891–1941,” in Making Imperial Mentalities: Socialisation and British Imperialism, ed. J. Mangan. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990, 46–73.

Burton, M. Antoinette. “The White Woman’s Burden: British Feminists and the Indian Woman, 1865–1915,” Women’s Studies International Forum 13, no. 4 (1990): 295–308.

Butcher, G. John. The British in Malaya 1880–1941: The Social History of a European Community in Colonial South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1979. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 301.4512105951033 BUT)

Callan, Hilary and Shirley Ardener, eds. The Incorporated Wife. London: Croom Helm, 1984.

Davin, Anna. “Imperialism and Motherhood,” History Workshop 5, no. 1 (Spring 1978): 9–65. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

De Vere J. Allen. “Malayan Civil Service 1874–1941: Colonial Bureaucracy/Malayan Elite,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 12, no. 2 (April 1970): 149–78. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Harper, T. N. “Globalism and the Pursuit of Authenticity: The Making of a Diasporic Public Sphere in Singapore,” Sojourn 12, no. 2 (1997): 261–92. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Harper, Tim. “The British ‘Malayans’,” in Settlers and Expatriates: Britons Over the Seas, ed. Robert Bickers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, 233–69. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 305.341 SET)

Hollen Lees, Lynn. “Being British in Malaya 1890–1940.” Journal of British Studies 48, no. 1 (January 2009): 76–101. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Hyam, Ronald. Empire and Sexuality. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990.

Jones, Margaret. “Permanent “Boarders”: The British in Ceylon, 1815–1960.” In Settlers and Expatriates: Britons Over the Seas, ed. Robert Bickers (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 205–32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 305.341 SET)

Lambert, David and Alan Lester, eds. Colonial Lives Across the British Empire: Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.0971241 COL)

Lester, Alan. “Imperial Circuits and Networks: Geographies of the British Empire.” History Compass 4, no. 1 (January 2006): 124–41.

Lowrie, Claire. Masters and Servants: Cultures of Empire in the Tropics. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 325.341095957 LOW)

McDevitt, P. F. May the Best Man Win: Sport, Masculinity and Nationalism in Great Britain and the Empire 1880–1935. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Pomfret, David. Youth and Empire: Trans-Colonial Childhoods in British and French Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.230959 POM)

Procida, Mary. Married to the Empire: Gender, Politics and Imperialism in India 1883–1947 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 954.035 PRO)

Shennan, Margaret. Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya 1880–1960. 2nd ed. Singapore: Monsoon Books, 2015. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.500421 SHE)

Strobel, Margaret. European Women and the Second British Empire. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991.

NOTES

-

Ethel Colquhoun, Two on Their Travels (London: W. Heinemann, 1902), 15. (Call no. RRARE 910.4 COL) ↩

-

Henry Norman, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East: Travels and Studies in the British, French, Spanish and Portuguese Colonies, Siberia, China, Japan, Korea, Siam and Malaya (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1895), 41. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 950 NOR-[KSC]; microfilm NL25995) ↩

-

Alongside the material listed in the bibliography of this paper, further sources relating to this topic can be found online at https://reference.nlb.gov.sg/. ↩

-

Frank Swettenham, British Malaya: An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1948), xv. (From National Library Singapore call no. RSING 959.5 SWE) ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Blue Book for the Year (Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1881), 1–17. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB; microfilm NL2896) ↩

-

For a detailed discussion of the nature of the British colonial civil service, see J. De Vere Allen, “Malayan Civil Service 1874–1941: Colonial Bureaucracy/Malayan Elite,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 12, no. 2 (April 1970): 149–78. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

The names of non-white administrators are recorded in the Straits Settlements Civil Service List. Examples include cadet James Anthonisz, who was born in Ceylon of mixed Dutch descent, and George Galistaun Seth, who had attended university in Calcutta and in 1902 was a cadet in the Colonial Secretary’s Office in Singapore. Straits Settlements, The Straits Settlements Civil Service List Showing The Civil Establishments, Names and Designations of the Civil Servants of Governmentt (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1884), 19 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RARE 351.2 STR; microfilm NL5821); Straits Settlements, The Straits Settlements Civil Service List Showing the Civil Establishment, Names and Designations of the Civil Servants of Government (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1902), 69. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RARE 351.2 STR; microfilm NL5821) ↩

-

Antoinette M. Burton, “The White Woman’s Burden: British Feminists and the Indian Woman, 1865–1915,” Women’s Studies International Forum 13, no. 4 (1990): 299. ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Blue Book for the Year (Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1911), 3 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB; microfilm NL2896); Blue Book for the Year, 1881, 1. ↩

-

For example: Khoo Kay Kim, Elinah Abdullah and Wan Meng Hao, Malays/Muslims in Singapore: Selected Readings in History 1819–1965 (Selangor: Pelanduk Publications, 2006 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8992805957 MAL); Rajesh Rai, Indians in Singapore, 1819–1945: Diaspora in the Colonial Port City (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 909.049141105957 RAI) ↩

-

David Lambert and Alan Lester, “Introduction: Imperial Spaces, Imperial Subjects,” in Colonial Lives Across the British Empire: Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century, ed. David Lambert and Alan Lester (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.0971241 COL) ↩

-

John Cameron, Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India: Being a Descriptive Account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wellesley and Malacca: Their Peoples, Products, Commerce and Government (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1865), 284. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Blue Book for the Year, 1881, 1. ↩

-

Andrew Gilmour, An Eastern Cadet’s Anecdotage (Singapore: University Education Press, 1974), 28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 920 GIL) ↩

-

Frank Kershaw Wilson, Frank Kershaw Wilson’s Letters Home, January 1915 – December 1916, While As Administrative Cadet, Singapore (MSS. Ind.Ocn.S.162). Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. (Singapore: National Library Board, 2009). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5703 WIL; microfilm copy held in NLB). Copyright restrictions placed on the letters by the original donors prevent them from being quoted directly without securing the consent of these donors or their heirs. ↩

-

Frank Kershaw Wilson to Mother, 10 September 1915. ↩

-

“News in Brief,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 March 1939, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Straits Times, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States Annual (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1908), 30 (From National Library Singapore, microfilm NL5876); “Stella Michell,” Devon Mitchells, n.d. ↩

-

“Malayans at Home,” Malaya Tribune, 27 March 1937, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Walter Del Mar, Around the World Through Japan (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1904), 70. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.41 DEL-[JSB]) ↩

-

Isabella Bird, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither (London: John Murray, 1883), 111 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 BIS; microfilm NL 5876); Minnie Farlow, “The Christmas Mail,” in Singapore Skits in Prose and Verse (Singapore: Singapore and Straits Print. Off., 1896), 1–2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 820 MF; microfilm NL5827) ↩

-

John Dill Ross, The Capital of a Little Empire: Descriptive Study of British Crown Colony in the Far East (Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, 1898). (From National Library Online; microfilm NL 5829) ↩

-

Tim Harper, “The British ‘Malayans’,” in Settlers and Expatriates: Britons Over the Seas, ed. Robert Bickers (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 41. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 305.341 SET) ↩

-

For an outline of the idea of an imagined community as a socially constructed group identity see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 2006). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 320.54 AND) ↩

-

Robert Hamilton Bruce Lockhart, Return to Malaya (New York: Putnam, 1936), 149. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 LOC-[JSB]; microfilm NL18264) ↩

-

Emily Innes, The Chersonese With the Gilding Off (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1885), 170. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 915.951043 INN) ↩

-

Bodleian Library, “Papers of Sir Ernest Birch (Box 1 of 12): Personal Diaries of Mrs Margaret Birch, 1896–1904, With a Loose Programme of Amateur Theatricals at the Tanglin Club, 1885,” private records, 187619–29. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. MSS.Ind.Ocn.s.354; microfilm NAB 0803) ↩

-

R. V. K. Applin, Across the Seven Seas (London: Chapman & Hall, 1937), 49 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 355.00924 APP-[RFL]); John Erskine Kempe, John Erskine Kempe, Diaries, vol. 1–10, December 1911 to 1934, vol. 7, MSS.Ind.Ocn.S.94 (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1986). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.503 KEM; microfilm copy held in NLB). Despite spending his career in the Federated Malay States, Kempe was married at St Andrew’s Cathedral in June 1920; D. H. Ridout to Sir Arthur Evans, 31 March 1917; The National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore: Investigation of Mrs Acton, Wife of Roger Acton of the Straits Settlements Civil Service, private records, 01/01/1916-31/12/1917. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. FCO 141/16032) Electronic copy held by the National Archives of Singapore. Part of an investigation into the wife of a colonial administrator brought to Singapore to face questions from the British authorities. https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/private_records/record-details/ee6835c9-662e-11e4-859c-0050568939ad ↩

-

Clive Dalton, A Child in the Sun (London: Eldon, 1937), 97. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 DAL-[JSB]; microfilm NL18263) ↩

-

Shelley Leigh Hunt and Alexander S. Kenny, Tropical Trials: A Handbook for Women in the Tropics. (London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1883), 9. ↩

-

Florence Caddy, To Siam and Malaya in the Duke of Sutherland’s yacht, “Sans Peur” (London: Hurst and Brackett, 1889), 77 (From National Library Online); Annie Brassey, A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months, 3rd ed. (London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1878), 409. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Del Mar, Around the World Through Japan, 71. ↩

-

P. McDevitt, May the Best Man Win: Sport, Masculinity and Nationalism in Great Britain and the Empire 1880–1935 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 2–4; Richard J. H. Sidney, In British Malaya To-Day (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1927), 276. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 SID-[RFL]) ↩

-

William T. Hornaday, Two Years in the Jungle: The Experience of a Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo With Maps and Illustrations (London: K. Paul, Trench, 1885), 294. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.043 HOR; microfilm NL7981) ↩

-

See for example T. J. Keaughran, Picturesque and Busy Singapore (Singapore: Lat Pau Press, 1887), 2–3 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 915.951 KEA; microfilm no. NL5829); Edwin A. Brown, Indiscreet Memories: 1901 Singapore Through the Eyes of a Colonial Englishman (London: Kelly & Walsh, 1935), 6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 BRO; microfilm NL16352); J. S. M. Rennie, Musings of J.S.M.R., Mostly Malayan (Singapore: Malaya Pub. House, 1933), 6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 REN; microfilm NL8447) ↩

-

Roland St. J. “The Merry Past: The Good Old Days,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore: Being Some Account of the Capital of the Straits Settlements From Its Foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, vol. 2. (2016; repri., London: John & Murray, 1921), 509. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS] ↩

-

“Introduction,” Straits Produce 1, no. 3 (1893): 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51033 SP) ↩

-

T. J. Keaughran, “Picturesque and Busy Singapore,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 17 January 1887, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Braddell, “The Merry Past: The Good Old Days,” 465. ↩

-

Ronald Hyam, Empire and Sexuality (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 207; Janice N. Brownfoot, “Sisters Under the Skin: Imperialism and the Emancipation of Women in Malaya c. 1891–1941,” in Making Imperial Mentalities: Socialisation and British Imperialism, ed. J. Mangan (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 46–73. ↩

-

Lockhart, Return to Malaya, 110–11; Margaret Strobel, European Women and the Second British Empire (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), 1. ↩

-

Mary Procida, Married to the Empire: Gender, Politics and Imperialism in India 1883–1947 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 954.035 PRO) ↩

-

Procida, Married to the Empire, 56. ↩

-

“The Health of the Governor,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 29 August 1893, 6; Sylvia, “The Little Things of Life,” Straits Times, 13 July 1906, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

ichard Myrddin Williams to Katherine Paterson, 28 December 1914; Richard Myrddin Williams: Letters to Katherine Paterson, 1913–1918, envelopes 6 and 12, 17 September 1916. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5703 WIL) ↩

-

Birch, “Papers of Sir Ernest Birch (Box 1 of 12): Personal Diaries of Mrs Margaret Birch, 1896–1904, With a Loose Programme of Amateur Theatricals at the Tanglin Club, 1885,” box 1. ↩

-

Dorothy Cator, “Talk Given on 16th March 1909: Some Experiences of Colonial Life,” in Honourable Intentions: Talks on the British Empire in South-East Asia Delivered at the Royal Colonial Institute 1874–1924, ed. Paul H. Kratoska (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1983), 228–95. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 HON) ↩

-

Innes, The Chersonese With the Gilding Off, 242–49. ↩

-

“Children in Singapore,” Straits Times, 11 June 1914, 10 (From NewspaperSG); Alfred Harmsworth Northcliffe, “My Journey Round the World,” in Travellers’ Singapore: An Anthology, ed. John Bastin (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994), 193. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5705 TRA-[JSB]) ↩

-

Blue Book for the Year, 1881, 1. ↩

-

David Pomfret, Youth and Empire: Trans-Colonial Childhoods in British and French Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), 24 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.230959 POM); Anna Davin, “Imperialism and Motherhood,” History Workshop 5, no. 1 (Spring 1978): 12. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Hugh Clifford, “Rachel,” Living Age 239 (1903): 468–535; Davin, “Imperialism and Motherhood,” 10; Norman, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, 38. ↩

-

Pomfret, Youth and Empire, 24. ↩

-

John Dill Ross, Sixty Years: Life and Adventure in the Far East, vol. 1 (London: Hutchinson, 1911), 94–5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959 ROS; microfilm NL14209) ↩

-

Dalton, A Child in the Sun, 274. ↩

-

Andrew Carnegie, Round the World (New York: [s.n.], 1957), 154. ↩

-

Walter Makepeace, “Concerning Known Persons,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 2, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brook and Roland St. Braddell (London: John & Murray, 1921), 423–42. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

For a discussion of the idea of empire families within the context of British India, see Elizabeth Beuttner, Empire Families: Britons and Late imperial India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) ↩

-

“Sir Ernest Birch: Biographical Sketch of Noted Administrator,” Straits Times, 17 January 1930, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Topics of the Day,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 29 January 1883, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Social and Personal,” Straits Times, 25 June 1927, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Makepeace, “Concerning Known Persons,” 441. ↩

-

Bird, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, 113; Brassey, A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”, 414; Hornaday, Two Years in the Jungle, 299. ↩

-

Geo C. Morant, Odds and Ends of Foreign Travel (London: Charles and Edward Layton, 1913), 133. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 901.4 MOR) ↩

-

Dill Ross, Sixty Years: Life and Adventure in the Far East, 115; Myrddin Williams, Richard Myrddin Williams: Letters to Katherine Paterson, 1913–1918, 24 May 1913. ↩

-

Frank Swettenham, “Talk Given on 21st March 1896: British Rule in Malaya,” in Honourable Intentions: Talks on the British Empire in South-East Asia Delivered at the Royal Colonial Institute 1874–1924, ed. Paul H. Kratoska (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1983), 190. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5 HON). For relations between Europeans and leading members of the Chinese community see T. N. Harper, “Globalism and the Pursuit of Authenticity: The Making of a Diasporic Public Sphere in Singapore,” Sojourn 12, no. 2 (1997): 275. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Swettenham, “Talk Given on 21st March 1896: British Rule in Malaya,” 187; Procida, Married to the Empire, 167–68. ↩

-

“Local Education,” Malaya Tribune, 28 August 1917, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Robert Bickers, “Introduction: Britains and Britons over the Seas,” in Settlers and Expatriates: Britons Over the Seas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 8. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 305.341 SET) ↩