Early Multi Ethnic Roman Catholic Communities, c 1830s to 1850s

By Dr Marc Sebastian Rerceretnam

INTRODUCTION

In historical studies of Malaysia and Singapore, the British colonial practice of “divide and rule” in its governing of ethnic communities is a prominent feature.1 Race relations – then and now – are often viewed in light of how the British controlled and manipulated Asian communities. The persistence of such concepts and practices2 has implanted the false impression that early Singaporean communities lived in separate spheres and did not interact in any meaningful way.3 Except for certain Peranakan communities that predate British colonialism, there is little evidence in current scholarly research to show that consistent interaction, friendships or such as J. S. Furnivall, utilising the idea of the “plural society”, have claimed that interracial colonies were disadvantaged because society was broken into segregated segments who lived “side by side, yet without mingling”.4

To counter these misconceptions, this paper examines new evidence of early inter-ethnic relations within a new emerging community, starting in the first half of the 19th century. One of the premises of this study is that multiracial interaction was rather extraordinary in the context of the prevailing colonial framework of society and labour, in which British administrators intentionally manufactured social, economic and political differences between communities.5 For example, under colonialism, the British cultivated a political hegemony which strongly implied their social, cultural and political “superiority” and compared this to “inferior” races, thus justifying their role as colonial masters. They often listed hierarchies of races delineating industriousness versus laziness, entrepreneurial abilities and even cultural traits they deemed desirable, along purely racial lines. The contemporary notion of the cultural superiority of the different Chinese ethnic groups, most of whom were deemed more industrious than the “lazy” Malay races, originates from this period.

This preoccupation with “race” and notions of superiority, according to current historical research covering the Malay Archipelago, did not exist prior to British colonialism. Charles Hirschman claims “racial division” simply did not exist before that, while Collin Abraham claims that considerable harmony existed between the different groups and this was only upset with the arrival of the British. Wang Gungwu has stated that multicultural or multiethnic-type society was an integral part of the “local reality” prior to the arrival of the British.6

This paper examines the early growth of the Roman Catholic community in Singapore, which began in earnest in 1833.7 While most other communities at this time were bound by some degree of clan affiliation, ethnic identity or language, the Roman Catholic community was different. From its early days, it was an amalgam of people from different backgrounds. It is possible that divisions did exist, but there were also more opportunities to overcome them than previously recognised. In effect, this community predates modern concepts of multicultural and multiracial Singapore by at least a century.

The data used in this study comes mostly from church records rather than government records, as colonial governments largely ignored the registration of Asian communities. These communities were seen merely as a source of cheap labour,8 therefore not warranting recording in official statistics, except when it impacted governance and control. Consequently, this study draws its data from contemporary accounts, oral interviews, individual entries in church-based birth, marriage and death registers, as well as newspaper reports.

The Establishment of the Roman Catholic Church in Singapore

The population of early colonial Singapore comprised three major racial groupings – Malay, Chinese and Indian – alongside several smaller communities. In the period immediately after 1819, the island was dominated by various Malay communities – mainly fishermen, boatmen and farmers. This included the Bugis, who dominated shipping and trade between Singapore and the Celebes region, importing a variety of spices, coffee and gold dust. By 1821, the population of the island was estimated at 4,727 persons, which included 2,851 Malays, 1,159 Chinese and 29 Europeans.9 The following year, South Indians began arriving. Within a few years, a large number of Chinese immigrants arriving from various parts of China’s Guangdong province saw them become the largest racial group. There were also a number of Peranakan Chinese arriving from around the region who were largely brokers, shopkeepers and general merchants. The newer Chinese arrivals – at this stage mostly “Fokiens” (probably Teochews)10 – were more involved in local industry.11

Christianity arrived in the Malay Archipelago with the Portuguese invasion of Melaka in 1511. However, the religion they brought with them had little long-term effect on local populations in the region. Consequently, it remained within the limited confines of its small community of mixed Malay-Portuguese “Kristang” descendants in Melaka. It took several centuries before a new wave of Christian evangelisation became apparent with the arrival of British interests, and then generally with the arrival of non-Muslim immigrants from the late 1700s. In 1781, with the help of the Sultan of Kedah, French Roman Catholic missionaries set up a station in Kedah, where they oversaw a group of refugee Roman Catholics from Siam.12 Following the British occupation of Penang island in 1786, this parish moved to the new island outpost. By the early 19th century, the Roman Catholic church was the largest Christian denomination in the Malay Archipelago.13

With the establishment of a British trading post on the island of Singapore in February 1819, French priest Reverend Imbert visited in 1822 and reported to the Bishop of Siam that the island had 12 or 13 Roman Catholics who lived “wretched” lives.14 By 1832, French missionaries had formed a permanent base in Singapore with Reverend Jean-Baptiste Boucho (later Bishop) and Padre Anselmo Yegros,15 after they were granted rent-free land by the British colonial government on Bras Basah Road for the purpose of worship. Within a year, the first Roman Catholic chapel was consecrated on 5 May 1833, on the site of the former St Joseph’s Institution (today the Singapore Art Museum). This small chapel measured a modest 18.3 metres by 9 metres.16

Between 1832 and 1839, the congregation grew relatively quickly, picking up speed from 1842, when inroads were made with the conversion of large numbers of China-born Teochew settlers. With steady growth came the need to expand beyond the little chapel, and so by 1841 fundraising for a proper church began. The Church of the Good Shepherd (now Cathedral) building was completed six years later in 1847.17

Growth of New Multiracial Congregations

Church archival records show that the majority of the early lay congregation was made up of Roman Catholic Melakans from the Peranakan Kristang community. This community probably arrived soon after the establishment of the colonial outpost, encouraged by the newly appointed Resident of Singapore, William Farquhar, and attracted by higher wages and good prices.18 Song Ong Siang claimed the church had approximately 300 Asian adherents in 1833, of whom “nine-tenths” were Malay-Portuguese descendants from Melaka.19 Song’s figures are hard to corroborate, but church records from the period do show the Melakan Peranakan Kristang community accounting for more than half of all marriage and baptism ceremonies between 1832 and 1843. This was followed by the Chinese, and to a lesser extent Indians, Eurasians from Penang, India, Bencoolen and Macao, and Europeans. There appear to have been no locally born ethnic Chinese, Indians or Peranakans in this early congregation.20

Making up the second-largest ethnic group in the 1830s congregation were the Teochews, who hailed from Guangdong, China. For some reason, the early conversions of these adherents were not listed in the baptism registers, but there is clear evidence of baptisms taking place as early as September 1833.21 Evangelisation among the Teochew migrants in Singapore began with the church’s inception in 1832.22 The first recorded conversion was in December 1839, in which Rev. John Tschu (1783–1848), a Canton-born priest, converted a wealthy Teochew merchant.23 By 1842, there was a big jump in conversion numbers and this accelerated further from 1844. In 1846, a new Teochew-centred church – St Joseph’s Church – was opened in rural Bukit Timah to cater to the large community of Teochew workers and planters living in the area.24

Intermarriages Within the Early Roman Catholic Church

Despite the British colonialists’ push to divide local communities, there is clear evidence that the Roman Catholic church in the 19th century did not discourage intermarriages and even facilitated unions between its racially diverse congregants. In December 1848, Fr. Jean Marie Beurel, a key figure in the Roman Catholic church in Singapore, noted that men from China came “without women”, and when they came “here they marry”.25 This point was highlighted by Rerceretnam (2012), looking at church records dating back to the latter half of the 19th century, which show that such interracial marriages took place with the assistance of related church facilities such as orphanages. The 2012 study posited, however, that this occurrence was “relatively rare” until the second or third decade of the 20th century.26

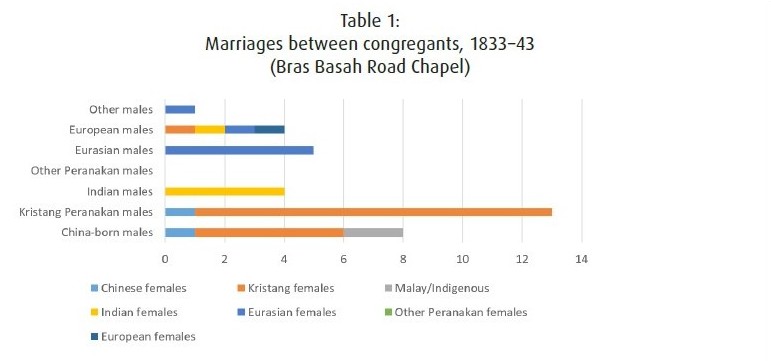

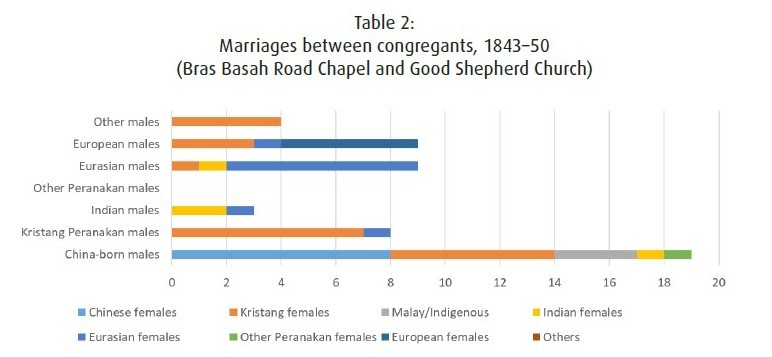

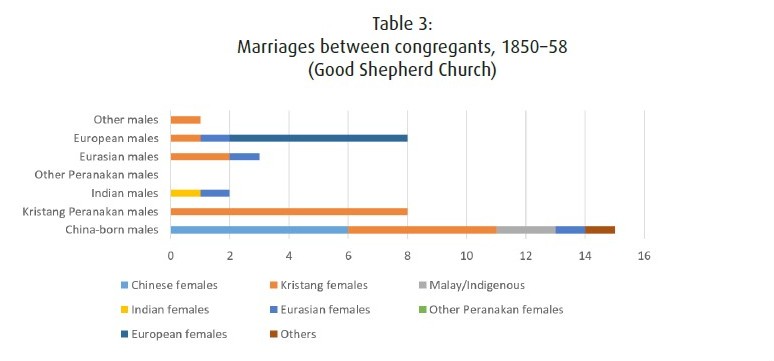

The present study, having been provided access to earlier records, shows unmistakably that intermarriages took place within the racially mixed congregation and were more prevalent than previously believed, most significantly between newly arrived China-born Teochew males and females from the old Peranakan Kristang community.27 The graphs on page 62 address the marital unions from the reference point of the male partner,

largely because colonial society was primarily patriarchal in nature, and choices in marriage were often made from the perspective of the man.

Between 1833 and 1843, eight marriages involving China-born men were celebrated at the Roman Catholic chapel on Bras Basah Road, mostly with women from the Melaka-born Kristang Peranakan community. In addition, two married local women of Orang Asli descent28 and one married an ethnic Chinese woman. Within the Melaka-born Kristang Peranakan community, out of 19 marriages, 12 were between fellow Kristang members, one with a Chinese woman, five with Chinese men, and one with an Italian man. Among the Eurasians, there were five all-Eurasian unions, one intermarriage with a European and another with an unidentified male. There were four all-Indian marriages, and only one intermarriage with a European.

By 1843, the size of the Chinese congregation had grown considerably, possibly approaching or even overtaking the Melaka-born (and now often Singapore-born) Peranakan Kristang community. The number of marriages involving China-born males was more than double that of their Peranakan Kristang counterparts. Of the China-born males, many still married women from the Peranakan Kristang community, but even more formed unions with local-born Chinese women from Singapore, Riau, Lingga and the neighbouring region. In addition, there were a few unions with Malays (possibly orphans), one with a Peranakan woman (possibly Melakan Chinese), and one with an Indian girl from Bengal. Eurasian males began to marry outside their group – one to a Kristang woman and another to an Indian woman. Of the three Indian males married at the church, two married Indian women, and one a Eurasian woman. Unions involving European males seem to have remained relatively diversified.

The year 1853 was a significant one for the Good Shepherd Church. A large part of its original congregation left to join the newly completed St Joseph’s Church (Portuguese Mission)29 situated several hundred metres away on Victoria Street. For the first time, the numerical dominance of the church’s Teochew congregation came to the fore. At this stage, there were slightly more than 340 ethnic Chinese parishioners.30 Even the popular coupling of China-born Teochew males and Melaka-born Peranakan Kristang females seems to have subsided by late 1852. To a limited extent, this gap appears to have been taken up by Chinese women. After 1853, up to six women of Chinese descent married China-born Teochew males. Of these, one was born in Banten (west Java) and three were from China, while the origins of the other two were unspecified. In addition, unions involving China-born males include three women of non-Chinese descent, one from Borneo and two from Penang; there were only five unions with Peranakan Kristang women up to 1858.

From 1858 onwards, approximately two to four marriages were celebrated at the church annually. The number of intermarriages involving Chinese men decreased dramatically. Unions with the Peranakan Kristang community did not take place the way they did in previous decades. It appears that the Kristang community’s move to their new Portuguese Mission-controlled church had put a social wedge between the two groups. Starting in the 1830s, competition between the Portuguese Mission and the French Mission was a sore point for many decades. The Portuguese claimed ecclesiastical control of the region, but the issue was not resolved until 1886.31 It is highly likely that the feuding missions frowned on each other’s “rival” congregations and discouraged mixing on a social basis. Between 1858 and 1868, there was only one intermarriage between a Chinese male and a Peranakan Kristang female.32 The rest of the marriages appear to be with ethnic Chinese women.33

The situation at the rural St Joseph’s Church in Bukit Timah was more dire. Despite its relatively large congregation, only 72 marriages were celebrated between its inception in 1847 and 1880. These marriages appear to involve exclusively Chinese women, with the exception of one, involving an Indian woman from Melaka.34 Many of these Chinese women could have come from the orphanage run by the local Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, which was set up in 1855.35

Overview of Intermarriages, 1833 to 1858

Over the 25-year period between 1833 and 1858, a total of 125 marriages were celebrated under the auspices of the French Mission of the Roman Catholic church in Singapore. Of this number, 42 instances, or 33.6 percent, involved mixed-race couples. This figure is significant, as no other multiracial entity is known to have existed within colonial Singapore at the time.

It also should be noted that in colonial society, especially among the male population, many often knew “no racial or class barrier” when it came to sexual relations.36 It can therefore be assumed that, at a sexual level, many of these men were already familiar with the concept of a multiracial society. In addition, there appear to be very few direct references made by the French clergy to these intermarriages in their correspondence, suggesting that they did not see it as an issue. Whatever their motives were, it is clear they inadvertently facilitated interracial relationships at a formal yet intimate level.37

While the significance of mixed marriages is important in colonial Singapore, the numbers reported are still low, especially when seen in relation to the overall size of the congregation. No official statistics are available of the size of these early congregations, but estimates do exist. In 1833, a year after the establishment of the mission on Bras Basah Road, the congregation was assessed to be around 300.38 By 1851, this had climbed marginally to 340 (150 of whom were located at the Bukit Timah church site).39 Between 1833 and 1843, within the China-born community, there were only eight marriages, meaning that many more did not get the opportunity to marry – a point acknowledged by Beurel in July 1847, when he wrote how marriage among the resident Chinese “rarely happens at least in this island”.40

So, what was so special about these eight China-born men (see Table 1) that enabled them to find wives within the local Peranakan Kristang, Malay and indigenous communities? What did they have to offer the consenting families? According to Margaret Sarkissian (2005), during the British colonial period, the Peranakan Kristang community was divided into two distinct social groups. The upper class, referred to as the “Upper Tens”, tended to have Dutch or British family names (although some had Portuguese names too); they were literate, spoke English as a first language and were employed in white-collar jobs by their British masters. Then there were the poor “Portuguese”, who made up the lower class; they were mostly illiterate, spoke a local creolised form of Portuguese called Kristang and mainly worked as fishermen or fishmongers.41

It is not surprising that many members of the latter subgroup, being poor, would have taken the opportunity to align themselves with potentially promising China-born men, or even well-to-do merchants. The match between these two groups – the China-born Teochew men and the “Portuguese” women – was therefore a well-suited one. Conversely, there were no marriages between women of the Upper Tens and China-born Teochew men. The Upper Tens probably saw these men as socially inferior.

The Peranakan Kristang community were the most established of the various church communities in Singapore. Tracing their origins to 16th-century Melaka, not only were they the largest grouping within the new Singapore church, but like most of their fellow Peranakan community counterparts they benefited from a relatively balanced gender ratio-42 something the China-born Teochew community did not have. For the new immigrants, seeking a spouse meant taking time away from employment and travelling back home; this was an expensive exercise. The only other option was to find an appropriate and willing female partner locally.

But marrying a local woman was made very difficult by the low ratio of women to men, a problem not overcome until the 1930s. In 1823, the ratio of women to men in the Malay Archipelago was 1:8, by 1850 1:12 and in 1860 1:15.43 These numbers were echoed in Singapore, with one Chinese woman to 15 Chinese men in the mid-1860s, improving only slightly in the 1880s to 1:9.44 According to Seah Eu Tong’s 1848 account, among the Chinese, only shopkeepers or the Melaka-born could afford to marry, resulting in only 2,000 Chinese men in Singapore being married.45 These dynamics can be observed at the rural-based St Joseph’s Church (Bukit Timah). Since most of this community comprised poor farmers, they had no financial enticement to offer potential brides. Their opportunities for marriage were far more limited compared with their city-based brethren at the Good Shepherd Church, hence accounting perhaps for the mere 72 marriages held at the parish between 1847 and 1880.46

As a Roman Catholic, the only viable option for marriage was with a fellow Roman Catholic. Marriage under the auspices of the church would not allow marriage with a non-believer.47 Marriage with a Protestant was tolerated and occasionally allowed by the clergy, but only after the Protestant partner signed an oath to allow their partner to continue as a Roman Catholic and to bring up their children as Roman Catholics.48 The options open to the newly arrived China-born men were therefore daunting. In Singapore, seeking a wife in the resident Peranakan Chinese community was not an option, for during this period (1830s to 1860s) there is little to no evidence of a pre-existing Roman Catholic Chinese Peranakan community. Even if they did exist, this community was unlikely to accept lowly China-born sinkeh49 men within their ranks, though of course exceptions could be made if one was already established, regarded as industrious or possessing potential.50 There are occasional references to a very small number of locally born Chinese women in the church.51 However, this, too, was very rare at this stage. Song did observe in his 1923 book that the majority of Singapore Peranakan families only went back three or four generations before descending from a pure Chinese progenitor,52 which ties in with the findings of this study. Significantly, these early intermarriages between China-born men and Peranakan Kristang (both local-born and Melakaborn), Malay and indigenous women are therefore the start of a Singaporespecific Peranakan bloodline.

Marriages among the smaller groups, such as the Eurasians, Indians and Europeans, exhibit different dynamics. More recent Eurasian communities (18th and 19th centuries) that developed in places like Penang were generally the result of informal liaisons between local women and European colonial civil servants, soldiers or traders.53 Early Eurasian marriages (1833–43) appear to indicate a willingness to pair off mainly with fellow Eurasians. However, in the following years, there was a shift towards marriages with local Chinese, Peranakan Kristang and Indians. European marriages had the social and political advantage of being associated with the prestige of the colonial master.54 European marriages with all racial groups were easily accepted by all “subservient” communities; however, it is important to note that such marriages were relatively uncommon in that period. Illicit liaisons were common, and many Europeans preferred to have one or more Asian women at their sexual disposal rather than marry them.55 Indian marriages were negligible in number in comparison with their Chinese and Kristang Peranakan counterparts; large-scale Indian migration was still several decades away, coming only with the opening up of the rubber industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.56

Dynamics Behind Early Intermarriages

This research exists within an on-going academic discussion on the significance of intermarriage. Studies in the Netherlands by Matthijs Kalmijn and Frank van Tubergen found four determinants that supposedly influence a person’s propensity towards intermarriage. Firstly, the children of first-generation migrants, who are more integrated into their host society, are more likely to intermarry. Secondly, it is more common among those who arrive in their new country at a younger age. Thirdly, there is a higher inclination to intermarry among persons with a higher level of education. And finally, intermarriage is more common when there is an uneven group-specific sex ratio.57 Kalmijn and van Tubergen’s list of determinants is mostly borne out in the background of the early Teochew males. Many were young, educated and hence literate (many signed their marriage certificate in legible Chinese script) and lived in a society with a low group-specific sex ratio. However, the assertion that second-generation migrants are more likely to intermarry is contradicted by the Teochew men’s status as first-generation migrants.58

Kalmijn has also asserted that intermarriage attenuates cultural distinctiveness.59 This is arguable. When there are significant cultural differences (such as racial ones), the family is forced, to varying degrees, to address the issue of “identity”. Under normal circumstances, all things being equal, patriarchal societal structures tend to underplay the role of the mother. However, the underlying circumstances in this case are different.

The men were newly arrived foreigners with little to no connection with the region; moreover, as converts to Christianity, they were isolated from their kongsi (clan associations), and on a personal level, unwilling to even identify with it. The women, in contrast, had established Peranakan Kristang or Malay community support on hand. It has been found that in unions featuring such dynamics, the mother’s identity and cultural links would remain strong, even after the arrival of offspring.

For example, this scenario is similar to one described by Sylvia van Kirk, who studied marriage dynamics in unions between Aboriginal females and white male settlers in Canada. Kirk emphasises how early instances of such marriages often followed Aboriginal marital practices.60 However, with the expansion of European settler control over traditional Aboriginal lands, settler authority and customs were pushed much more to the fore.61 In a similar way, over the years, Chinese-Kristang family members would gradually be absorbed into the Teochew or general Chinese Peranakan cultural milieu – one that came to enjoy a strong presence in the region.

CONCLUSION

Intermarriage has a long history in the region. Marriages between foreign traders from the region and local women helped create different Peranakan communities that thrived prior to the arrival of British rule in the Malay Archipelago. Following the setting up of a British trading post in Singapore in 1819, new and larger communities of people were set up under the umbrella of British rule, one of which was the Roman Catholic community. All things being equal, the assumption was that intercultural linking would continue; however, this did not necessarily happen. Communities remained largely separate from each other and this rift widened when the British began introducing race-based policies to highlight their own role as colonial masters. Such policies also implied the superiority of one race over another, which in turn, created ambivalence and animosity between “competing” communities.

This study is an extension of a 2012 research paper that examined intermarriage in the latter half of the 19th century within the Asian communities of the Roman Catholic and Methodist churches in colonial Malaya and Singapore. By widening the exploration to encompass the decades immediately following 1819, it has found clear evidence that intermarriage within Singapore’s Roman Catholic community thrived during this earlier period. It shows how persons of different ethnicities, coming from a myriad of social, political and economic circumstances, were able to find commonalities to justify inter-ethnic unions. This ran contrary to British colonial “divide and rule” policies, which encouraged – and often forced – the different communities to remain separate. Within decades, however, these policies grew in strength and would discourage such intermarriages in the latter half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr Juliana Lim, Dr Yao Souchou and Khoo Ee Hoon. I would also like to extend my thanks to Lee Meiyu, Joanna Tan and Tan Huism (National Library Board, Singapore), Fr. John Paul Tan and Jennifer Joseph (Chancery of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore), Fr. Adrian Danker, Nevina D’Rozario and Andrew Koh (St Joseph’s Institution) for providing invaluable access to documents and for their feedback.

REFERENCES

Books

Abraham, Collin E. R. Divide and Rule: The Roots of Race Relations in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Institute for Social Analysis, 1997. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.9595 ABR)

—. The Naked Order: The Roots of Racial Polarisation in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Pelanduk, 2004. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8009595 ABR)

Alatas Hussein, Syed. The Myth of the Lazy Native. London: Frank Cass, 1977. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.800959 ALA)

Brass, Paul R. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Theory and Comparison. New Delhi: Sage, 1991, 76.

Bryce, James. The Roman and the British Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, 1914.

Buckley, Charles Burton. An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984. 245. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC). (1902 edition)

Cook, John. Sunny Singapore: An Account of the Place and Its People, With a Sketch of the Results of Missionary Work. London: Elliot Stock, 1907. 131. (From National Library Online; call no. RRARE 275.951 COO)

Hyam, Ronald. Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990, 202.

Makepeace, Walter, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J Braddell. One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE–[HIS]) (1921 ed.)

Nagata, Judith. Malaysian Mosaic: Perspectives From a Poly-Ethnic Society. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1979. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.29595 NAG)

Purushotam, Nirmala. “Disciplining Difference: Race in Singapore.” In Southeast Asian Identities: Culture and the Politics of Representation in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, edited by Joel S. Kahn. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 306.0959 SOU)

Rerceretnam, Marc. Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya and Singapore, c. 1870s–c. 1950s. Germany: VDM Verlag, 2011. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 320.569 RER)

Rudolph, Jeurgen. Reconstructing Identities: A Social History of the Babas in Singapore. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1998. (From National Library, call no. RSING 305.80095957 RUD)

Sng, Bobby E. K. In His Good Time: The Story of the Church in Singapore, 1819–1978. Singapore: Graduates’ Christian Fellowship, 1980, 22. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 275.957 SNG)

Stenson, Michael. Class, Race and Colonialism in West Malaysia: The Indian Case. Brisbane: University of Queensland, 1980. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 305.9595 ABR)

Stoler, Ann. “Sexual Affronts and Racial Frontiers: European Identities and the Cultural Politics of Exclusion in Colonial Southeast Asia.” In Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, edited by Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.8 COO)

Wang, Gungwu. “Continuities in Island Southeast Asia.” In Reinventing Malaysia: Reflections on Its Past and Future, edited by Jomo K. S. Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2001. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 303.409595 REI)

Journal articles

Andaya, Barbara Watson. “‘Come Home, Come Home!’”: Chineseness, John Sung and Theatrical Evangelism in 1930s Southeast Asia.” Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany), Occasional Paper Series_,_ no. 23, abstract, 2015.

Barr, Michael D. “Lee Kuan Yew: Race, Culture and Genes.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 29, no. 2 (1999): 145–66. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Carol, Sarah. “Intermarriage Attitudes Among Minority and Majority Groups in Western Europe: The Role of Attachment to the Religious In-Group.” International Migration 51, no. 3 (June 2013): 79. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

D’Cruz, M. J. “Indian Associations and the Coolies,” The Indian (August 1925): 94–5.

Embong, A. R. “Ethnicity and Class: Divides and Dissent in Malaysian Studies.” Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 3 (December 2018): 283–6. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Hirschman, Charles. “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology.” Sociological Forum 1, no. 2 (Spring 1986): 338 (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Holden, Philip. “A Man and an Island: Gender and Nation in Lee Kuan Yew’s “The Singapore Story.” Biography 24, no. 2 (March 2001): 405. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Kalmijn, Matthijs. “Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 396–7. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Kalmijn, Matthijs and Frank van Tubergen. “Ethnic Intermarriage in the Netherlands: Confirmations and Refutations of Accepted Insights.” European Journal of Population 22, no. 4 (2006): 375–7.

Loos, Tamara. “History of Sex and the State in Southeast Asia: Class, Intimacy and Invisibility.” Citizenship Studies 12, no. 1 (2008): 29, 33.

Peacock, James L. “Plural Society in Southeast Asia.” High School Journal 56, no. 1 (October 1972): 1 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Rerceretnam, Marc. “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore: A Case Study of Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Roman Catholic and Methodist Asian Communities.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 43, no. 2 (June 2012): 302–3, 302–23.

Sarkissian, Margaret. “Being Portuguese in Malacca: The Politics of Folk Culture in Malaysia.” Etnografica, 9, no. 1 (May 2005): 152.

Tan, Beng Hui. “Protecting Women: Legislation and Regulation of Women’s Sexuality in Colonial Malaya.” Gender, Technology and Development 7, no. 1 (2003): 28.

Thomas, T. G. “Some of Our Needs.” The Indian (April 1925): 6–7.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. “From “Marrying-In” to “Marrying-Out”: Changing Patterns of Aboriginal/Non-Aboriginal Marriage in Colonial Canada.” Frontiers 23, no. 3 (2002): 2 (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website)

Wright, Nadia. “Farquhar and Raffles: The Untold Story.” BiblioAsia, 14, no. 4 (January–March 2019)

Sound recorded material

Wee, Philip Peng Leng. Oral history interview by P. Wee and M. Wee, 1904–1991, 18 August 1981.

Archival material

“Good Shepherd.” Baptism Registers 1 (1832–1867)

“Good Shepherd.” Liber Matrimonium 2–111 (1833–1857): various.

“St. Joseph’s Church (Bukit Timah).” Liber Matrimonium (1847–1861)

Websites

Eric Guerassimoff, Eric. “The Gangzhu of Johor: Memories of a French Missionary in Malaysia (1859–1870).” Etudes Chinoises, 15, no. 1 (1997): 107.

“History of the Catholic Church in Singapore: The Virtual Exhibition: St. Joseph’s Church.” The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore, n.d.

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. London: John Murray, 1923, 46. (From National Library Online)

Tan, Martino and Jonathan Lim, “Online Brouhaha Over Heng Swee Keat’s Comments Shows More S’poreans Ready for Non-Chinese PM Sooner Than Later.” Mothership, 30 March 2019.

Wong, Pei Ting. “Older Generation of S’poreans Not Ready for Non-Chinese PM: Heng Swee Keat.” Today, 29 March 2019.

Theses and unpublished material

Dertien, Kim. “Irrevocable Ties and Forgotten Ancestry: The Legacy of Colonial Intermarriage for Descendants of Mixed Ancestry.” Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 2008.

Liew C., “Persecution of Chinese Christians in Early Colonial Singapore 1845–1869.” Unpublished historical inquiry report, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore, 2016, 40–1.

McNamara, Anthony. “The Letters of Fr. J. M. Beurel Relating to the Establishment of St. Joseph’s Institution Singapore,” Translated, edited and with a monograph by Rev. Brother Anthony St. Xavier’s Institution, Penang, private records, 1987. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. 152; microfilm NA 1334)

14 Williams, Kenneth M. “The Church in West Malaysia and Singapore: A Study of the Catholic Church in West Malaysia and Singapore Regarding Her Situation as an Indigenous Church.” PhD diss., Catholic University of Leuven, 1976, 93.

NOTES

-

Collin E. R. Abraham, Divide and Rule: The Roots of Race Relations in Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Institute for Social Analysis, 1997), 13 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.9595 ABR); Syed Alatas Hussein, The Myth of the Lazy Native (London: Frank Cass, 1977), 7 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.800959 ALA); Michael D. Barr, “Lee Kuan Yew: Race, Culture and Genes,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 29, no. 2 (1999): 145–66 (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website); Michael Stenson, Class, Race and Colonialism in West Malaysia: The Indian Case (Brisbane: University of Queensland, 1980) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 305.9595 ABR); Marc Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore: A Case Study of Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Roman Catholic and Methodist Asian Communities,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 43, no. 2 (June 2012): 302–3, 307–9; A. R. Embong, “Ethnicity and Class: Divides and Dissent in Malaysian Studies,” Southeast Asian Studies 7, no. 3 (December 2018): 283–6. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Barr, “Lee Kuan Yew: Race, Culture and Genes” 146–8; Philip Holden, “A Man and an Island: Gender and Nation in Lee Kuan Yew’s “The Singapore Story,” Biography 24, no. 2 (March 2001): 405. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Wong Pei Ting, “Older Generation of S’poreans Not Ready for Non-Chinese PM: Heng Swee Keat,” Today, 29 March 2019; Martino Tan and Jonathan Lim, “Online Brouhaha Over Heng Swee Keat’s Comments Shows More S’poreans Ready for Non-Chinese PM Sooner Than Later,” Mothership, 30 March 2019; Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 302. ↩

-

James L. Peacock, “Plural Society in Southeast Asia,” High School Journal 56, no. 1 (October 1972): 1 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Stenson, Class, Race and Colonialism in West Malaysia, 1–2. ↩

-

Abraham, Divide and Rule, viii, 6–7, 13–18, 22; Stenson, Class, Race and Colonialism in West Malaysia, 6–7; Marc Rerceretnam, Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya and Singapore, c. 1870s–c. 1950s (Germany: VDM Verlag, 2011), 30, 94–5, 108–11 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 320.569 RER); Nirmala Purushotam, “Disciplining Difference: Race in Singapore,” in Southeast Asian Identities: Culture and the Politics of Representation in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, ed. Joel S. Kahn (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1998), 55–56. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 306.0959 SOU). Arguments challenging the responsibility of British colonialism for race relations have surfaced with the work of Paul Brass and Francis Robinson, who assert that fundamental differences did exist between various colonised Asian Hindu and Muslim communities in India; see Paul R. Brass, Ethnicity and Nationalism: Theory and Comparison (New Delhi: Sage, 1991), 76. ↩

-

Charles Hirschman, “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology,” Sociological Forum 1, no. 2 (Spring 1986): 338 (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website); Colin Abraham, The Naked Order: The Roots of Racial Polarisation in Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Pelanduk, 2004) (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8009595 ABR); Wang Gungwu, “Continuities in Island Southeast Asia,” in Reinventing Malaysia: Reflections on Its Past and Future, ed. Jomo K. S. (Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2001), 24–5 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 303.409595 REI); However, Nagata noted how individuals had no qualms exploiting others of the same ethnic group, especially if there were marked superordinate-subordinate distinctions. Nagata claimed many did not understand issues relating to class, with many rarely viewing this as a product of social inequality despite the fact such views were already observed within some Asian communities as early as the 1920s and 1930s. Judith Nagata, Malaysian Mosaic: Perspectives From a Poly-Ethnic Society (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1979), 3 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.29595 NAG); Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: John Murray, 1923), 46 (From National Library Online); Rerceretnam, Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire, 20; T. G. Thomas, “Some of Our Needs,” The Indian (April 1925): 6–7; M. J. D’Cruz, “Indian Associations and the Coolies,” The Indian (August 1925): 94–5. ↩

-

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 245. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC). (1902 edition) ↩

-

Tamara Loos, “History of Sex and the State in Southeast Asia: Class, Intimacy and Invisibility,” Citizenship Studies 12, no. 1 (2008): 29, 33. ↩

-

Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 344. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE–[HIS]) (1921 ed.) ↩

-

The literature is not clear about which dialect groups dominated. Makepeace et al. (1921) are quite unclear and the author believes Makepeace et al. may be mixing “Fokiens” up with both Hokkien and Teochew dialect groups (345–6). ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke and Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, 1991, 1921, 28, 344–5, 346–7; According to Lee Poh Ping, there “already existed a Teochew agricultural settlement located in the interior of the island and devoted to growing gambier and pepper” (pre-1819), although this point is not accepted by Jurgen Rudolph (1998), who says there isn’t enough evidence to support the claim. ↩

-

Kenneth M. Williams, “The Church in West Malaysia and Singapore: A Study of the Catholic Church in West Malaysia and Singapore Regarding Her Situation as an Indigenous Church” (PhD diss., Catholic University of Leuven, 1976), 93; Rerceretnam, Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire, 49–50. ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke and Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, 1991, 1921, 235; John Cook, Sunny Singapore: An Account of the Place and Its People, With a Sketch of the Results of Missionary Work (London: Elliot Stock, 1907), 131. (From National Library Online; call no. RRARE 275.951 COO) ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 1984/1902, 242. ↩

-

Spanish Padre Anselmo Yegros was mistakenly sent by the Portuguese Mission in Goa to Singapore to administer the Roman Catholic community. However, his already resident Portuguese counterpart, originally from Macao, refused to recognise this authority, and they parted ways. Padre Yegros appears to have struck up a friendship with the French Mission and worked with them until his departure in early 1833. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 1984/1902, 244–5. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 1984/1902, 248. ↩

-

Nadia Wright, “Farquhar and Raffles: The Untold Story,” BiblioAsia, 14, no. 4 (January–March 2019); Bobby E. K. Sng, In His Good Time: The Story of the Church in Singapore, 1819–1978 (Singapore: Graduates’ Christian Fellowship, 1980), 22 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 275.957 SNG); Makepeace, Brooke and Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, 1991, 1921, 343. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 46. Song quite rightfully points out how Buckley (1902) wrongly observed that most of these adherents were of Chinese descent. ↩

-

“Good Shepherd,” Baptism Registers, vol. 1 (1832–67): various; “Good Shepherd,” Liber Matrimonium, vols. 2–111 (1832–1857): various. ↩

-

Liew C., “Persecution of Chinese Christians in Early Colonial Singapore 1845–1869” (Unpublished historical inquiry report, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore, 2016), 40–1. On 10 September 1833, Fr. Albrand mentions baptising four Chinese men, the youngest of whom is 25 years old. ↩

-

Liew, “Persecution of Chinese Christians in Early Colonial Singapore 1845–1869,” 39–40. ↩

-

Eric Guerassimoff, “The Gangzhu of Johor: Memories of a French Missionary in Malaysia (1859–1870),” Etudes Chinoises 15, no. 1 (1997): 107; “Good Shepherd.” See entry from December 1839. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867, 1984/1902, 251. ↩

-

Letter addressed to the Superior and Directors of the Seminary of the Foreign Missions, dated 7 December 1847. Brother Anthony McNamara, “The Letters of Fr. J. M. Beurel Relating to the Establishment of St. Joseph’s Institution Singapore,” translated, edited and with a monograph by Rev. Brother Anthony St. Xavier’s Institution, Penang, private records, 1987. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. 152; microfilm NA 1334) ↩

-

Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 318–21. ↩

-

“Good Shepherd,” various. See entries April 1833 to July 1843. ↩

-

Philip Wee Peng Leng, oral history interview by P. Wee and M. Wee, 1904–1991, 18 August 1981; “Good Shepherd.” See entry from 6 September 1841. ↩

-

“History of the Catholic Church in Singapore: The Virtual Exhibition: St. Joseph’s Church,” The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore, n.d. ↩

-

Liew, “Persecution of Chinese Christians in Early Colonial Singapore 1845–1869,” 72. ↩

-

Rerceretnam, Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire, 50. ↩

-

“Good Shepherd.” See entry on 31 January 1867. ↩

-

It is difficult to determine where these Chinese women came from. Information in these marriage registers is inconsistent and often scant. ↩

-

“St Joseph’s Church (Bukit Timah) (1847–61),” Liber matrimonium. See entry on October 1870. ↩

-

Current research appears to indicate a large number of reasons why girls were left with the orphanage, from poverty and sickness to abandonment. Unfortunately, access to the CHIJ archival records was denied to the researcher on the basis that many of the girls were originally from “disreputable” backgrounds. ↩

-

Tan Beng Hui, “Protecting Women: Legislation and Regulation of Women’s Sexuality in Colonial Malaya,” Gender, Technology and Development 7, no. 1 (2003): 28; Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 318. ↩

-

Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 323. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 46. ↩

-

Liew, “Persecution of Chinese Christians in Early Colonial Singapore 1845–1869,” 72. ↩

-

McNamara, “The Letters of Fr. J. M. Beurel Relating to the Establishment of St. Joseph’s Institution Singapore,” 5. ↩

-

Margaret Sarkissian, “Being Portuguese in Malacca: The Politics of Folk Culture in Malaysia,” Etnografica, 9, no. 1 (May 2005): 152. ↩

-

Jeurgen Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities: A Social History of the Babas in Singapore (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1998), 98–9. (From National Library, call no. RSING 305.80095957 RUD) ↩

-

Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 318. ↩

-

Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities, 98; Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 32–3. ↩

-

Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities, 96. ↩

-

St Joseph’s Church (Bukit Timah) (1847–61).” See entry from October 1870. ↩

-

Marriages with non-Catholics or even non-Christians did exist and do appear in church records occasionally, especially in relation to the baptism of their common child. However, this was extremely rare. ↩

-

“Good Shepherd.” Examples of this can be found on the following dates, 19 October 1850, 12 July 1854, 25 November 1854, 13 February 1855 and 9 June 1857. ↩

-

The term sinkeh was a derogatory term for newly arrived poor Chinese coolies. ↩

-

Rudolph, Reconstructing Identities, 100, 106. ↩

-

“Good Shepherd.” See entries from 29 July 1850, 10 September 1850, 9 November 1847, 4 November 1846, 14 June 1853, 17 October 1853. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 712. ↩

-

Ann Stoler, “Sexual Affronts and Racial Frontiers: European Identities and the Cultural Politics of Exclusion in Colonial Southeast Asia,” in Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, ed. Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 210, 235. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 909.8 COO) ↩

-

Concepts of racially implied associations with “masculinity” were prevalent at the time. Hence some races were seen as the male “aggressor” while others were labelled as “passive” and feminine. Ronald Hyam, Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 202. ↩

-

Hyam, Empire and Sexuality, 90, 94, 109, 158–9, 213; Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 210. ↩

-

Stenson, Class, Race and Colonialism in West Malaysia, 16; Rerceretnam, Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire, 293. Large-scale Indian migration to the Malay Archipelago only took off from around 1905. ↩

-

Matthijs Kalmijn and Frank van Tubergen, “Ethnic Intermarriage in the Netherlands: Confirmations and Refutations of Accepted Insights,” European Journal of Population 22, no. 4 (2006): 375–7. ↩

-

Kalmijn and Tubergen, “Ethnic Intermarriage in the Netherlands,” 375–7; Rerceretnam, “Intermarriage in Colonial Malaya and Singapore,” 303–4; Kim Dertien, “Irrevocable Ties and Forgotten Ancestry: The Legacy of Colonial Intermarriage for Descendants of Mixed Ancestry” (master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 2008); Sylvia Van Kirk, “From “Marrying-In” to “Marrying-Out”: Changing Patterns of Aboriginal/Non-Aboriginal Marriage in Colonial Canada,” Frontiers 23, no. 3 (2002): 2 (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Matthijs Kalmijn, “Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends,” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 396–7. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Van Kirk, “From “Marrying-In” to “Marrying-Out,” 2. ↩

-

Van Kirk, “From “Marrying-In” to “Marrying-Out,” 3. ↩