Writing from the Periphery: Dorothy Cator in British North Borneo

Janice Loo explains how the travel writings by women such as Dorothy Cator reveal the complex relationships between colonisers and the colonised.

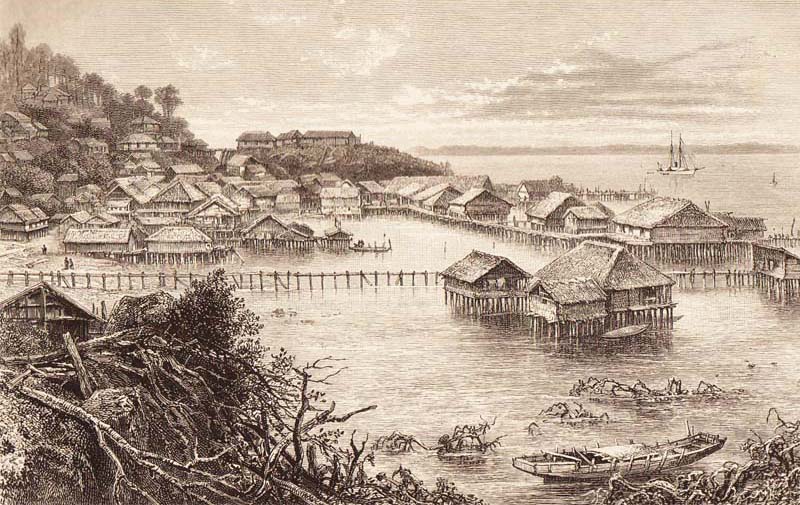

Sandakan, formerly known as Elopura (1889). Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.

Sandakan, formerly known as Elopura (1889). Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.The journey was slow as the vessel steered carefully through treacherous waters riddled with corals and submerged islands. Gradually, the bay, “one of the finest harbours in the world”,1 came into view; its entrance guarded by “fine red sandstone cliffs backed with forest-clad hills rising to a height of about 800 feet.”2 Douglas and Dorothy Cator had at last reached Sandakan, the capital of British North Borneo (present-day Sabah, Malaysia), where the newly wedded couple were to be based for more than two years between 1893 and 1896.3

Formerly known as Elopura, or “Beautiful City”, Sandakan was a modest settlement perched on the edge of the British Empire adjacent to the Dutch East Indies. Singapore, the nearest centre of commerce and point of telegraphic communication with Europe, was literally 1,000 miles away.4 From this remote outpost, the pair made excursions off the coast to Taganak as well as deeper inland to the Gomanton Caves and Penungah, the furthest government station. Cator accompanied her husband, a magistrate in the British North Borneo Government, when official duties took him into the interior. It was from their encounters and interactions with indigenous communities in the famous “head-hunting country”5 that the title of her travelogue was derived.

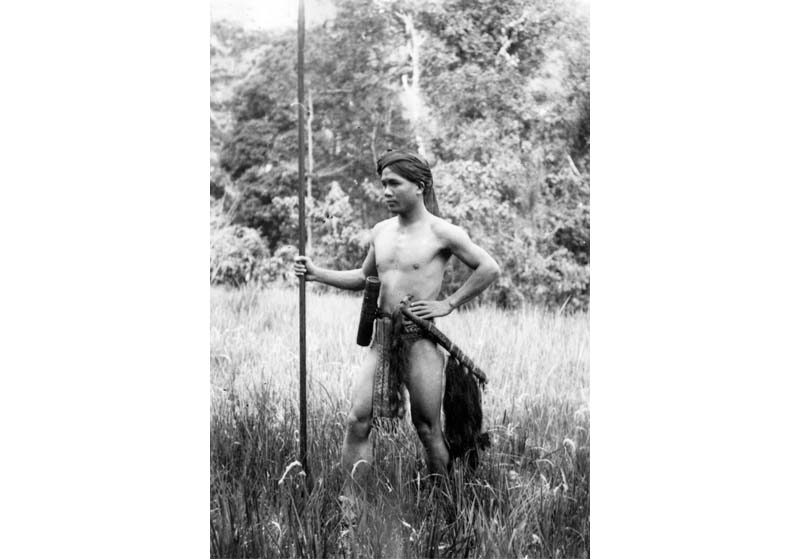

At a glance, Everyday Life Among the Head-hunters and Other Experiences East to West (1905) offered the standard fare in colonialist representations of the tropics. Descriptions of landscapes, flora and fauna, commercial products (sago, sugarcane, edible birds’ nests, tobacco, timber) and local cultures (Chinese, Malays, Sulus, Dayaks, Dusuns, Bajows, Muruts) blended with anecdotes, impressions and musings to form a lively narrative made even more compelling by the author’s indefatigable wit.

Although Cator identified with British imperialism, her account of North Borneo questioned the dominant discourses on gender and race that structured colonial society. While suggesting rhetorical alternatives, Cator’s writings did not amount to counter-hegemonic resistance against the status quo but rather contained “moments of outbreak [and] discursive freedoms […] when imperial and patriarchal conventions, though seldom disappearing, lose their hermeneutic force.”6

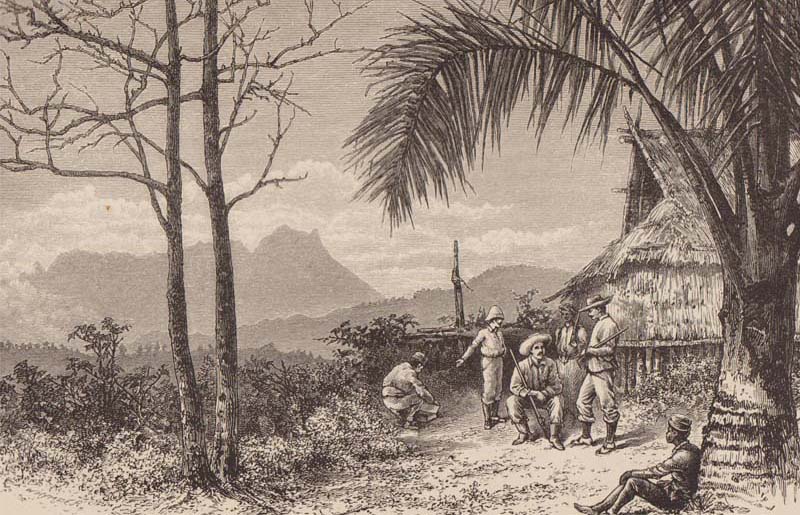

This illustration of head-hunting Dayaks was featured in the Illustrated London News in October 1887. Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.

This illustration of head-hunting Dayaks was featured in the Illustrated London News in October 1887. Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.Writing Power

Imperial dominance, in terms of cultural hegemony, was enacted in colonial travel writing, where the coloniser – epitomised by the “figure of the settler-colonial white man”7 – possessed and exercised “the capacity to build and sustain some truths about land and people, and to denigrate and marginalise them.”8 Women, however, faced difficulties in adopting the same authoritative and imperialist narrative voice because of their interstitial position as the “inferior sex within the superior race,”9 betwixt power and the lack thereof.10

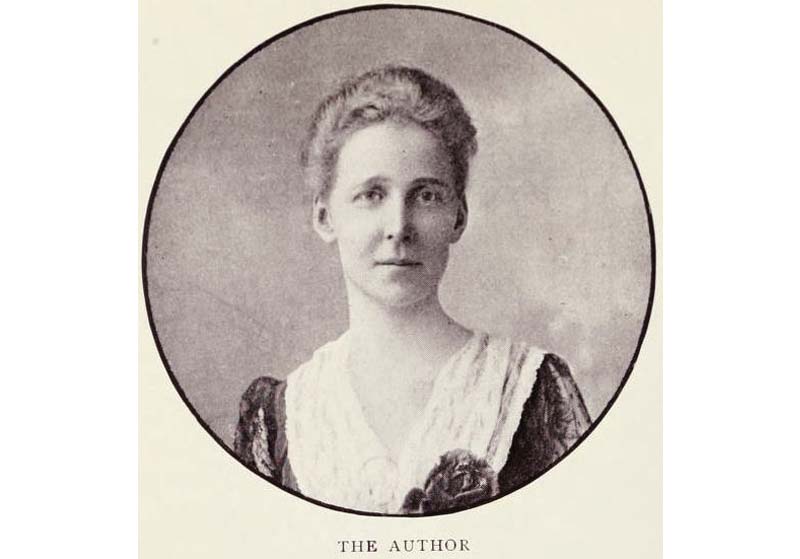

This can explain for the vacillations between self-assuredness and diffidence in Cator’s attitude towards her writing, as seen in the “Introduction” of her book:

“As I have travelled where no other white woman has ever been, and lived among practically unknown tribes both in Borneo and Africa, I have often been asked to write a book; but till now I have wisely refused, as I have no idea how it ought to be done. I have a hazy notion that I ought to know all about prehistoric and glacial periods, whereas they convey nothing to my mind; and the subject of composed and decomposed porphyrite rocks and metamorphic states is unintelligible gibberish to me: so if this ever appears in print, please don’t expect too much”.11

Cator’s claim to narrative authority, based on self-identification as a white woman with original, first-hand knowledge of unexplored territories and undiscovered cultures, was undermined by her own confessed ignorance of how to systematically document what she knew. Cator acknowledged the epistemological superiority of science (incidentally a male domain), yet her tongue-in-cheek disparagement of its language as “unintelligible gibberish” seemed to indicate otherwise. Notwithstanding her self-deprecation, her ability to quote obscure geological terms could be seen as a subtle act of showing off while maintaining a cloak of modesty. Cator’s negotiation of her feminine subjectivity at the intersection of gender and race in the colonial context produced some degree of ambivalence, self-contradiction and inconsistence in her writing.

The writer, Dorothy Cator. Everyday Life Among the Head-Hunters (1905).

The writer, Dorothy Cator. Everyday Life Among the Head-Hunters (1905).Women for Empire

Female identification with imperialism typically echoed and endorsed masculine imperial rhetoric, which was rooted in white superiority and its “civilising” impulse. By invoking Eurocentric reasoning and Orientalist tropes (the “savage” native, the “enterprising” Chinese) recurrently deployed in the hegemonic (masculine) rhetoric of imperial domination, Cator took on the position of British (male) colonialism in an act of appropriation that signified both subversion and submission.12

Cator portrayed the different ethnic communities in North Borneo within the overarching paradigm of a “Pax Britannica”, emphasising the unprecedented peace and security afforded by firm but benevolent British governance. She described the Chinese as “a most industrious, law-abiding people if only they are governed properly [emphasis added]”13; the Dayaks “make splendid soldiers and best of friends, as they are faithful and trustworthy […] Held in with an iron hand [emphasis added] they are very valuable [otherwise] they are worse than wild beasts”14; the Bajows, “a dark-skinned, wild sea-gipsy race roving from place to place – pirates until the English arrived [emphasis added], and the terror of the whole coast, but now living peaceable, quiet lives”15; likewise, the Dusuns “have settled down wonderfully quietly under British rule, and [gave] very little trouble.”16 Recounting petty disputes that her husband helped resolve, Cator remarked that “the people’s unquestioning confidence in the justice of an Englishman is very touching,”17 thus vindicating her conviction in the integrity and fairness of British rule.

Cator further underscored the superiority of British imperialism by representing the conduct of other European powers in diametric contrast as inhumane and unjust. She denounced the Spanish as “very bad colonists, cruel masters, who hate and are hated by the natives over whom they rule”18; the Dutch as being “inclined to look upon [the natives] as not merely a lower race than themselves, but lower than their animals” and they were responsible for the “most brutal cases of cruelty on the estates which [her husband] Douglas and the other magistrates had to inquire into.”19 This affirmed the conventional rationalisation for British intervention in terms of a moral obligation to rescue and extend protection to populations “outside the pale of civilisation.”20

Interestingly, Cator referenced narratives of feminine dominance in the domestic sphere, specifically the absolute superiority of the mistress to her servant, to justify colonial rule:

“Black races [referring to the natives] were, of course, never meant to be in the same position as white ones, any more than a kitchenmaid of a house, however excellent she may be, is made to be the equal of her mistress. They were meant to serve, not to rule; and it is entirely our faults when they fail in positions of authority in which we have placed them, for which and to which they were neither qualified nor born, but they wouldn’t have been given legs unless they were meant to stand on them [emphasis added].”21

Cator assumed the paternalist (or rather, maternalist) and patronising stance of the well-meaning colonial parent who claimed full responsibility for the failings of her native charges; this implied that it was native incompetence that necessitated colonial supervision. However, there appears to be an abrupt twist in the last sentence; the idiom “standing on your two feet” suggests that the native had the capacity to be independent and self-reliant. On that note, Cator’s endorsement of British imperialism and its ideological underpinnings nevertheless does not preclude other ruminations and self-reflexive critique that potentially disrupt the hegemonic discourse.

A Murut hunter. Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.

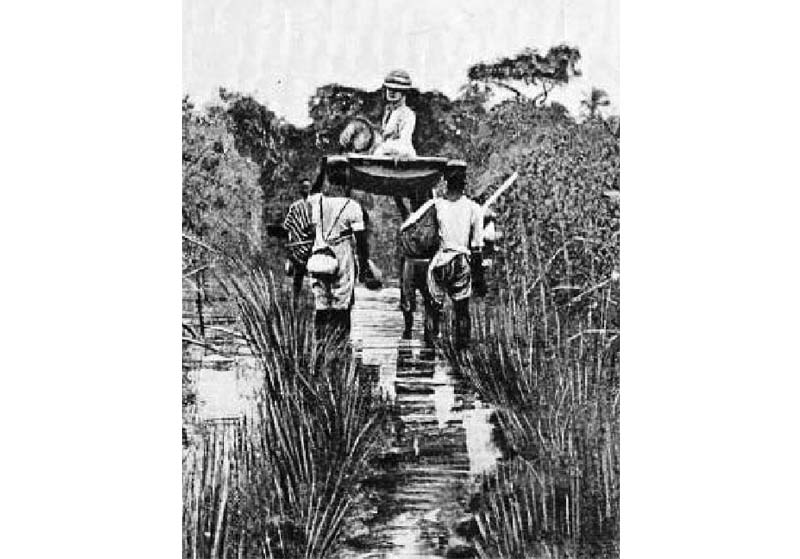

A Murut hunter. Courtesy of the Sabah Museum. The writer crossing a swamp in British North Borneo. Everyday Life Among the Head-Hunters (1905).

The writer crossing a swamp in British North Borneo. Everyday Life Among the Head-Hunters (1905).Talking Back

Empire conjured a romantic image of bold and industrious “pioneer men taming wild terrains into productivity and profitability”22 that stressed ideal white masculinity as “physical, responsible, productive and hardworking.”23 Women were excluded from this vision; Cator likened colonial society in Sandakan to “all other European communities in the Far East, where it is an understood thing that only the men should work and the ladies sleep and amuse themselves.”24 The fairer sex was presumed to make no active contribution to the imperial endeavour.

In response to the opinion of one governor that North Borneo was “no place for ladies,”25 Cator had begged to differ, explaining that “every lady by her mere presence ought to help to keep up the standard of a place.”26 By recreating British domestic and social life on the imperial frontier, women (specifically, wives) were regarded as bearers of white civilisation who kept their men from “going native”27, thereby preserving colonial respectability and prestige.28 Cator not only defended the role of women (albeit in a way that reinforced patriarchal discourses of femininity) but went further by countering that “it was certainly no place for boys.”29 “Boy” connoted male immaturity, inexperience and the proclivity for trouble and mischief – qualities that were inimical to empire-making. “We had among us the riff-raff of the world,” Cator complained, “and boys sent out without any religion or reverence for anything above themselves…”30

While Cator was not against imperialism, she was intensely critical of the haphazard and careless manner in which colonial rule was imposed:

It is a great pity that men and even boys, totally ignorant of native life and customs, are sent to rule, or rather to experiment on them, for it is nothing else but learning by blunder after blunder – a bitter experience to the native, if not to them – the things which belong to the peace of the country they have been sent to govern. Cases of this kind are constant, and might so easily be avoided. No one at home would dream of turning into their schoolrooms governesses who had not only never seen children, but had had no training in the art of teaching; and yet that is what we are doing constantly in out-of-the-way parts of the world, [emphasis added] because at the moment there is no one with any experience to send. Inexperience does such incalculable harm that one can’t help feeling how far better it would be to leave the natives alone till the necessary experience has been gained, even if it should risk an intertribal war [emphasis added].”31

Here, Cator drew an analogy using a different figure of feminine authority, the English governess, to the effect of exposing the severe shortcomings in colonial governance that could conceivably cast doubts on the idea of British superiority. Yet, imperial rhetoric remained intact as Cator continued to believe in the necessity of British intervention – it was a matter of having qualified administrators. Moreover, it was assumed that North Borneo would revert to a state of violence and anarchy in the absence of its white civilisers.

On the other hand, there were instances in which imperial rhetoric was exposed as sheer hypocrisy. The constructed differences that separated coloniser from colonised and legitimised the supremacy of the former over the latter was questioned when it came to the indigenous practice of head-hunting as Cator exclaimed:

“I don’t want to stand up for head-hunting, it isn’t nice! We civilised nations call it murder, and it is murder. But who are we to throw stones? [Emphasis added] Aren’t the means we take to satisfy our unquenchable thirst for gain, murder? […] And in our murder are any good qualities necessary? None! But fighting brings out the noblest parts of a savage, and in their home-life love and content reign; but civilised murder means misery and discontent, and homes turned into hell. If we took a being from some other planet and made him look at the two pictures, Barbarism and Civilisation, side by side – Paganism and Christianity – I don’t think his verdict as to who wanted the most teaching would be the same as ours.”32

Despite occupying a marginal position in the masculine space of the British Empire, the voices of women writing in colonial contexts, as exemplified by Cator, could be just as imperialising. However, this did not necessarily mean there was no leeway for deviating within permissible bounds, and sometimes, even for questions, reflections and provocations that chipped at the monolith of imperial rhetoric.

View of Mount Kinabalu (background) from the Tempasuk River (1889). Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.

View of Mount Kinabalu (background) from the Tempasuk River (1889). Courtesy of the Sabah Museum.

Janice Loo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She was the author of “A Quiet Revolution: Women and Work in Industrialising Singapore”, published in BiblioAsia Vol. 10, Iss. 2.

REFERENCES

Brownfoot, J.N. (1984). Memsahibs in colonial Malaya: A study of European wives in a British colony and protectorate 1900–1940 (pp. 189–210). In H. Callan & S. Ardener (Eds.), The incorporated wife. London: Croom Helm. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Cator, D. (1905). Everyday life among the head-hunters and other experiences east to west. London: Longmans, Green and Co. (Call no.: RCLOS 991.11 CAT)

Chakrabathy, D. (2000). Provincialising Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference (p. 5). Princeton: Princeton University Press. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Doran, C. (1998, June). Golden marvels and gilded monsters: two women’s accounts of colonial Malaya. Asian Studies Review, 22 (2), 175–192. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website.

Han, M.L. (2003, October). From travelogues to guidebooks: Imagining colonial Singapore, 1819–1940. Sojourn: Journal of Social issues in Southeast Asia, 18 (2), 257–278. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Levine, P. (Ed.). (2004). Gender and empire. New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: R 305.309171241 GEN)

Mills, S. (1991). Discourses of difference: An analysis of women’s travel writing and colonialism. London: Routledge. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Morgan, S. (1996). Place matters: Gendered geography in Victorian women’s travel books about Southeast Asia. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. (Call no.: RSING 820.9355 MOR)

Strobel, M. (1991). European women and the second British empire. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

The Singapore and Straits directory for 1894, containing also directories of Sarawak, Labuan, Siam, Johor and the Protected Native States of the Malay Peninsula and an appendix. (1890–1895). (1894). Singapore; The Singapore & Straits Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 382.09595 STR; Microfilm no.: NL1180)

NOTES

-

Cator, D. (1905). Everyday life among the head-hunters and other experiences east to west (p. 14). London: Longmans, Green and Co. (Call no.: RCLOS 991.11 CAT) ↩

-

Background information on the Cators was sorely lacking in Everyday life among the head-hunters as the author generally omitted names of persons, dates and other biographical details. The following profile of Douglas Cator in North Borneo was gleaned from the 1890 to 1895 editions of The Singapore and Straits Directory. Douglas Cator began his stint in the British North Borneo Government in 1889/90 as a 3rd Class Magistrate at Province Alcock. By 1891, he had transferred to Sandakan, becoming a cadet in the East Coast District and a 3rd Class Magistrate at the Police Court & Court of Requests, Sandakan. He was appointed Acting Assistant Government Secretary in 1892. The next year he returned home to fetch Dorothy. The pair married in London and immediately left for North Borneo. By 1894, Douglas was Secretary to the Governor and promoted to 2nd Class Magistrate. He continued to be Secretary in 1895 but relinquished his position as Magistrate. Dorothy Cator was listed in the “Ladies’ Directory” of British North Borneo for the years 1894 and 1895. The Cators ceased to be listed in the Directory from 1896 onwards. ↩

-

The Singapore and Straits directory for 1894, containing also directories of Sarawak, Labuan, Siam, Johor and the Protected Native States of the Malay Peninsula and an appendix (pp. 270, 272). (1894). Singapore; The Singapore & Straits Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 382.09595 STR; Microfilm no.: NL1180) ↩

-

Morgan, S. (1996). Place matters: Gendered geography in Victorian women’s travel books about Southeast Asia (p. 13). New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. (Call no.: RSING 820.9355 MOR) ↩

-

Chakrabathy, D. (2000). Provincialising Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference (p. 5). Princeton: Princeton University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings), quoted in Levin, P. (2004). Introduction: Why gender and empire? (p. 6). In P. Levine, (Ed.), Gender and empire. New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: R 305.309171241 GEN) ↩

-

Han, M.L. (2003, October). From travelogues to guidebooks: Imagining colonial Singapore, 1819–1940. Sojourn: Journal of Social issues in Southeast Asia, 18 (2), 257–278, p. 259. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Strobel, M. (1991). European women and the second British empire (p. xi). Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Doran, C. (1998, June). Golden marvels and gilded monsters: two women’s accounts of colonial Malaya. Asian Studies Review, 22 (2), 175–192, p. 176. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website. ↩

-

Meaning to adopt local ways, for example, in dress, language, mannerisms, diet and so on. ↩

-

Brownfoot, J.N. (1984). Memsahibs in colonial Malaya: A study of European wives in a British colony and protectorate 1900–1940 (pp. 189–190). In H. Callan & S. Ardener (Eds.), The incorporated wife. London: Croom Helm. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩