A Nation of Islands

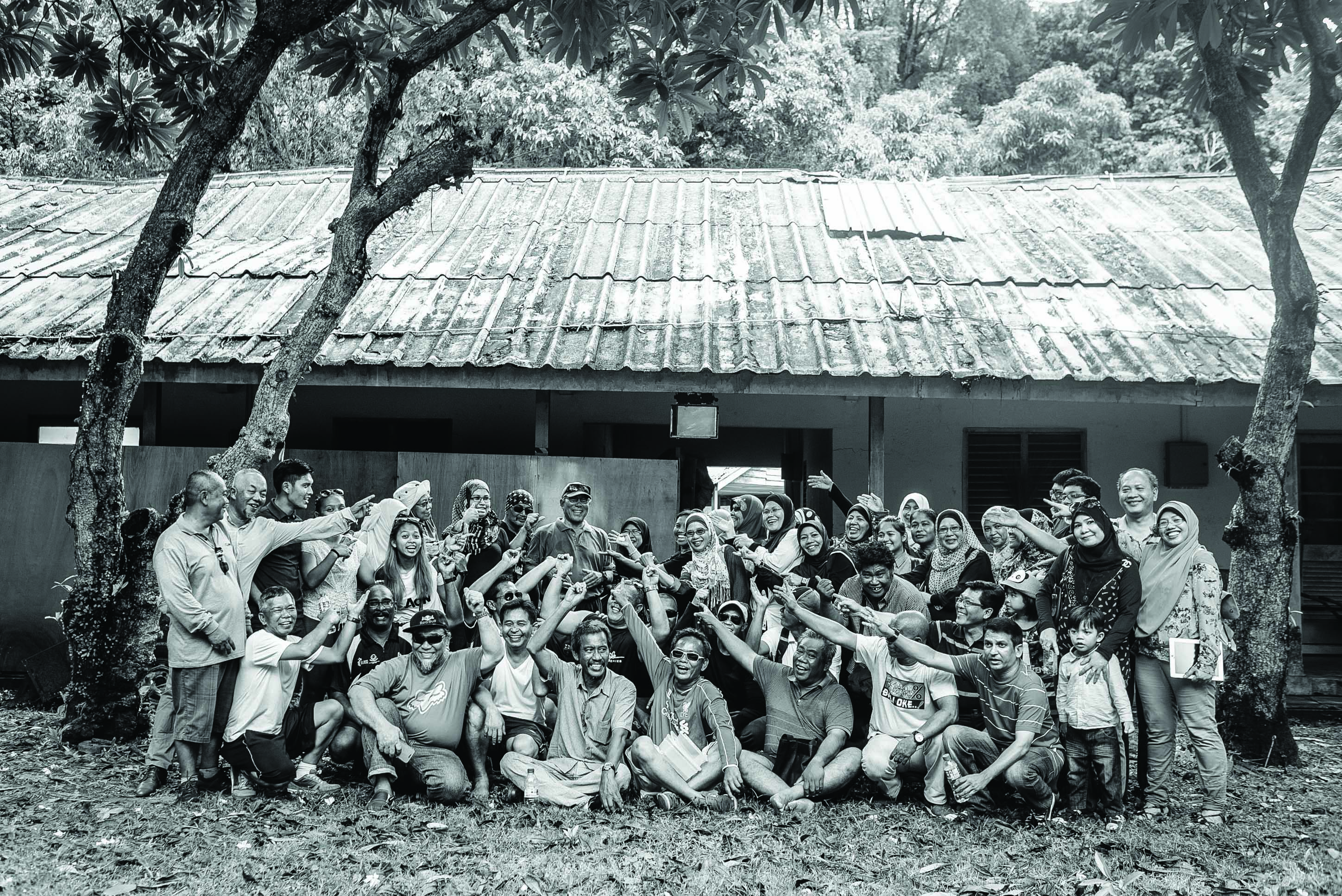

Students from the St John's Island English School take a group photograph with their teacher Mr Choo Huay Kim at the same place where they had their flag-raising ceremony every morning in the early 1970s. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Students from the St John's Island English School take a group photograph with their teacher Mr Choo Huay Kim at the same place where they had their flag-raising ceremony every morning in the early 1970s. Photo by Edwin Koo.

The caretaker of Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong) Temple on Kusu Island – just a 20-minute boat ride from Singapore – stands astride the short flight of stairs leading to the temple’s inner prayer sanctum, his eyes fixed on the jetty in the near distance.

It is the start of the ninth month of the Chinese lunar calendar, and thousands of devotees will travel to the island temple seeking blessings from Tua Pek Kong (God of Prosperity) and Guan Yin (Goddess of Mercy).

At the temple, caretaker Seet Seng Huat pauses and nods his head in the direction of a small group of men huddled at the furnace in the temple courtyard. The trio, in long sleeves and biker masks – with only their eyes visible – to protect themselves from the heat and smoke, offer to burn joss paper for devotees in return for a small donation.

Thick smoke billows out steadily from the narrow chimney of the furnace. The requests come thick and fast. As the two men take turns to collect joss paper and throw them into the furnace, the third man – probably the oldest – sits down.

“He comes here every season,” Seng Huat says, “and stays for a long time each time he visits.” He adds, “I think you should speak to him.”

“It has been over 60 years since I first started work here,” 91-year-old Mustari Dimu, a former resident of Lazarus Island, says in Malay. And every year since then, Mustari has returned to Kusu for a full month – maintaining his long family tradition and deep friendship with Seet Hock Seng, Seng Huat’s late father, the temple’s former caretaker.

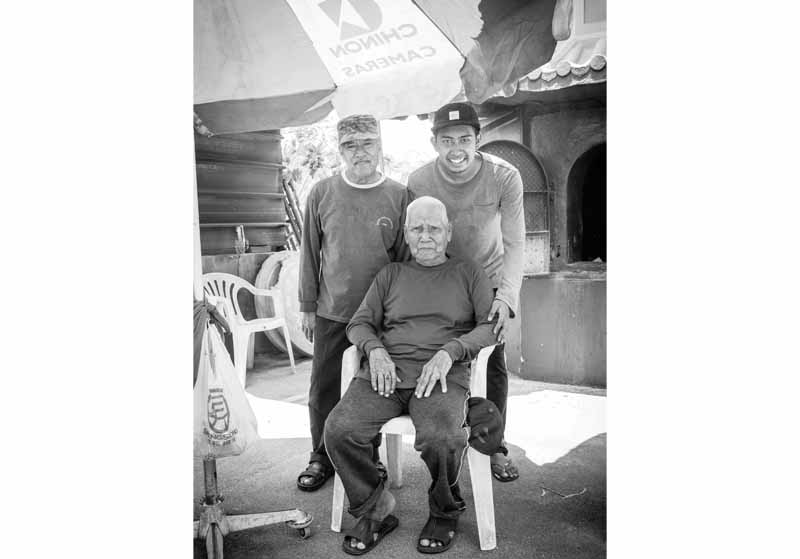

Seet Seng Huat is the current caretaker of the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Gong) Temple of Kusu Island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Seet Seng Huat is the current caretaker of the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Gong) Temple of Kusu Island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Mustari Dimu (centre), 92, with his son Sardon Mustari (left), 65, and Hazwari Abdul Wahid, 23, at the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong) Temple on Kusu Island. Photographed near the temple furnace, they help to burn joss paper during the peak season. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Mustari Dimu (centre), 92, with his son Sardon Mustari (left), 65, and Hazwari Abdul Wahid, 23, at the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong) Temple on Kusu Island. Photographed near the temple furnace, they help to burn joss paper during the peak season. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Such stories are not uncommon in “Island Nation”, a documentary project that recounts the stories of Singaporeans who once lived on the southern islands of Singapore, especially Sisters’ Island, Sentosa and Kusu Island.

Although most people think of Singapore as one large Island, it actually comprises a number small islands and islets – more than 60 at one point in time. As Singapore developed over the years, massive reclamation works swallowed up many of these islands and created new ones in the process. A number of these offshore islands, which were inhabited by people, were zoned for specific purposes and their residents relocated to mainland Singapore.

Using photographic stills, videography and archival footage, “Island Nation” is a documentary project that highlights the unique stories of these former islanders and weaves them into the broader Singaporean narrative of nationhood.

Living Histories

These islands represent an important part of Singapore’s heritage. According to Marcus Ng, researcher and co-curator of the exhibition “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands”,1 these islands represent the southernmost maritime boundary of the nation both physically and politically. “It is space where you are vulnerable because you are surrounded by elements you can’t control,” he says. “You are reminded that you live on an island.”

For Mustari, his involvement started as a young boy when his father, along with his uncles, worked sporadically for Hock Seng’s father at the temple. A young Mustari would often accompany his father on his trips to the temple. When Mustari’s uncles passed away, he decided to keep the tradition.

These days Mustari waits for a call in early September from Seng Huat. He then packs his clothes, and prepares food items such as tea, sugar and biscuits for the month-long stay. In fact, there is even a special locker reserved for him at the temple.

Mustari’s story reveals a deep attachment to the islands, “Dah biasa lah,” he says in Malay, meaning “used to it” referring to the islander’s lifestyle.

And he is not alone. Choo Huay Kim, 68, taught at St John’s Island English School from 1966 to 1976 – one of the few schools that existed on the Southern Islands. Choo was also an islander – he was born (in 1946) and raised on Pulau Sekijang Bendera, before it became known as St John’s Island.

“It was a well-known school, and some call it the Raffles Institution of the Southern Islands,” he quips, adding that the primary school only had 100 to 120 students. Posted back to the island to teach, he was also the school’s football coach and remembers how the team of 11 boys would squeeze into his modest Volkswagen to attend matches on the mainland.

“I felt for the boys because I was an island boy myself,” he says. Choo adds that they never had the things that children on the mainland enjoyed, such as proper facilities for competitive sports.

The bond that the students shared with their teacher as well as their fondness for the old way of life on these islands was evident when some 70 former islanders recently returned to visit their old school on St John’s Island, now used as living quarters for foreign workers.

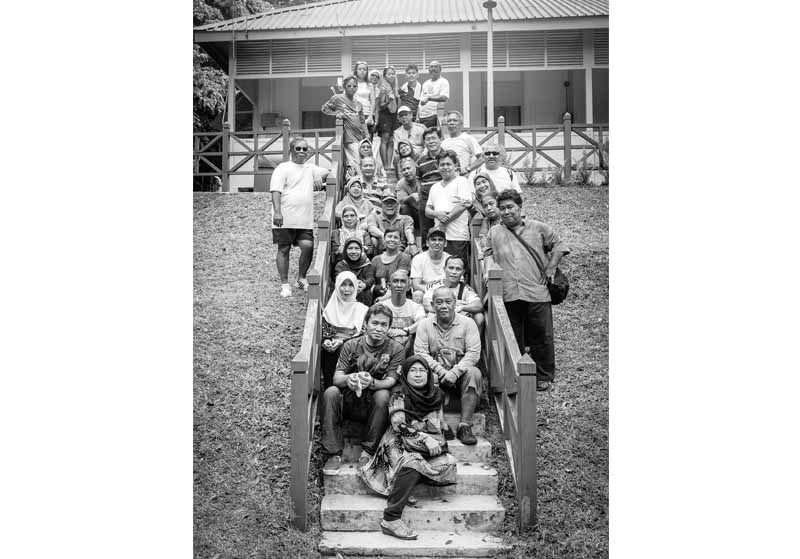

The St John's Island English School football team stand in front of the building where they once studied. This team went on to win the 1972 National Schools football tournament, led by their coach and teacher Choo Huay Kim (standing, far right). Photo by Edwin Koo.

The St John's Island English School football team stand in front of the building where they once studied. This team went on to win the 1972 National Schools football tournament, led by their coach and teacher Choo Huay Kim (standing, far right). Photo by Edwin Koo.

Island Living

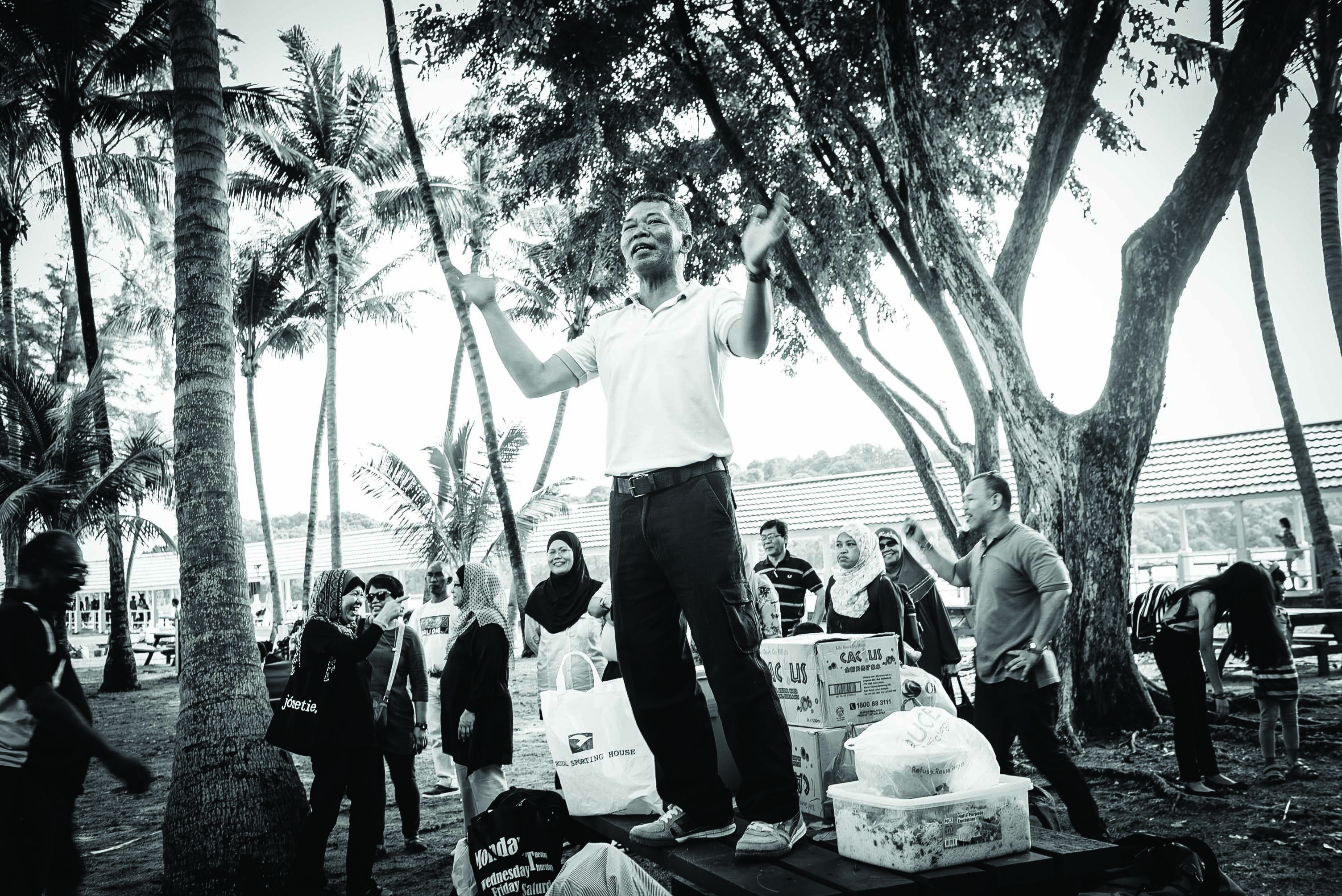

For many, the excursion to the islands of St John’s, Lazarus and Seringat on 9 November 2014 was like a taking a step back into time. The gotong-royong (community) spirit was truly alive that day as the former islanders prepared food that everyone could share. Funnily enough, despite the lack of coordination, no two dishes were the same!

A walking tour of the Islands became a chance for these folks to make new memories – posing for pictures with their former neighbours and taking photos with their smart phones of landmarks where they had lived or played – all the while reminiscing about old times.

Those who remembered pointed out landmarks that are now gone, such as a well, now covered up, that used to exist along the newly paved road on Lazarus Island. The football “boys” recalled their training sessions on St John’s, running along the beach and up the island’s solitary hill.

In the course of working on this project, we realised how interconnected the lives of the former islanders’ were and how important these islands still are to them today. Documenting their lives and what they remember of the islands is one way of capturing a slice of life that no longer exists in Singapore.

Hashim Daswan, 53, briefs his fellow former islanders during their visit to the southern islands on 9 November 2014. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Hashim Daswan, 53, briefs his fellow former islanders during their visit to the southern islands on 9 November 2014. Photo by Edwin Koo.

More than 70 former islanders and their family members returned to the islands of Sekijang Bendera (St John) and Sekijang Pelepah (Lazarus) for a walk down memory lane on Sunday, 9 November 2014. This photograph was taken outside a home that is now used as a chalet for the public. Photo by Edwin Koo.

More than 70 former islanders and their family members returned to the islands of Sekijang Bendera (St John) and Sekijang Pelepah (Lazarus) for a walk down memory lane on Sunday, 9 November 2014. This photograph was taken outside a home that is now used as a chalet for the public. Photo by Edwin Koo.

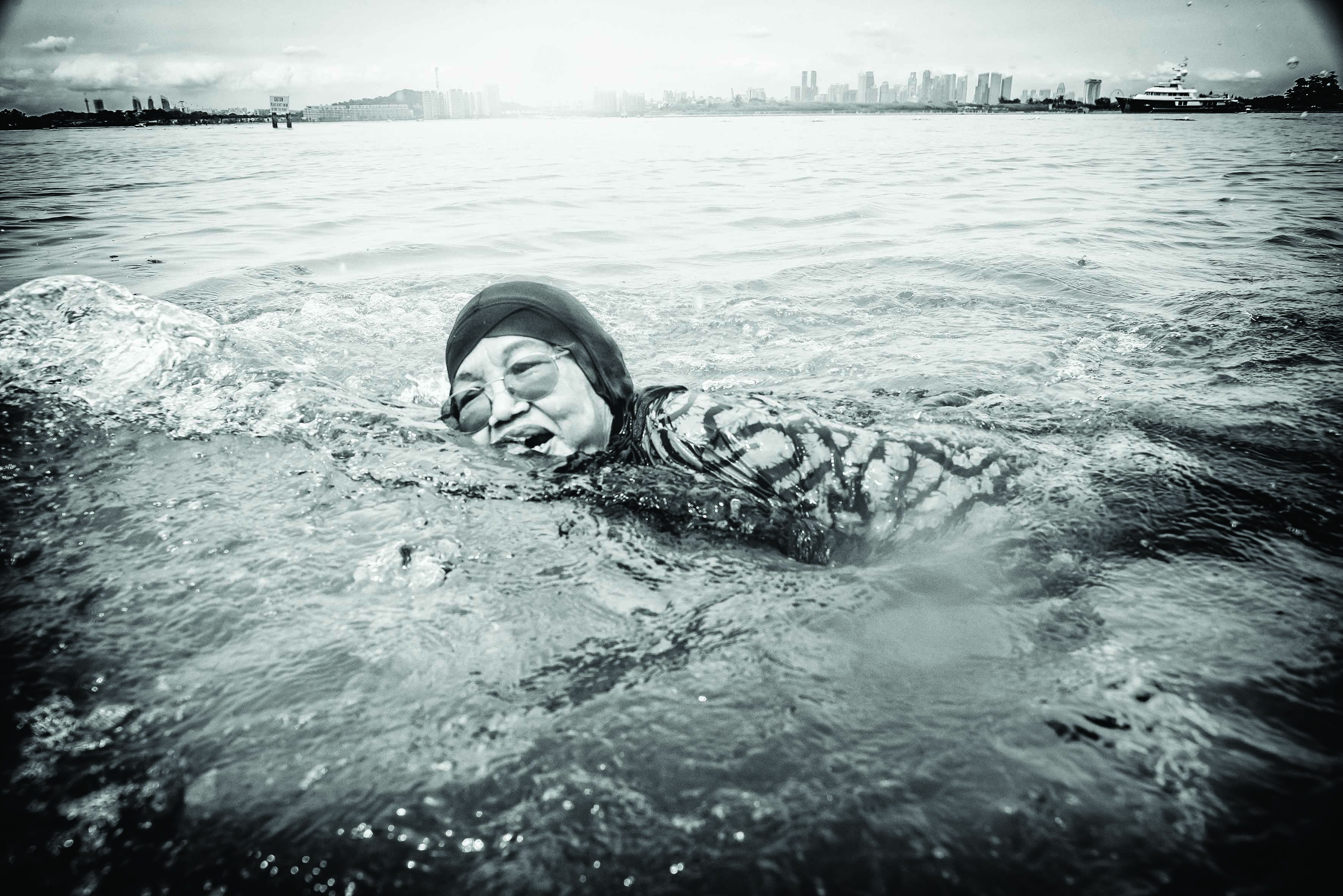

Mdm Bedah bte Din, 76, swims joyfully in the waters off St John Island, once known as Pulau Sekijang Bendera during the recent reunion of former islanders of that cluster. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Mdm Bedah bte Din, 76, swims joyfully in the waters off St John Island, once known as Pulau Sekijang Bendera during the recent reunion of former islanders of that cluster. Photo by Edwin Koo.

On St John's Island, Mohamed Sulih Bin Supian – born and bred on the island – and his wife Fuziyah use the space in front of their home to cook rice dumplings known as ketupat in preparation for Hari Raya Aidilfitri. He has special permission to live on the island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

On St John's Island, Mohamed Sulih Bin Supian – born and bred on the island – and his wife Fuziyah use the space in front of their home to cook rice dumplings known as ketupat in preparation for Hari Raya Aidilfitri. He has special permission to live on the island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Mohamed Sulih Bin Supian uses an electric bike to get around the island. Here he and his wife make their way to the St John's Island jetty to visit their children in time for Hari Raya Aidilfitri celebrations. Photo by Edwin Koo.

Mohamed Sulih Bin Supian uses an electric bike to get around the island. Here he and his wife make their way to the St John's Island jetty to visit their children in time for Hari Raya Aidilfitri celebrations. Photo by Edwin Koo.

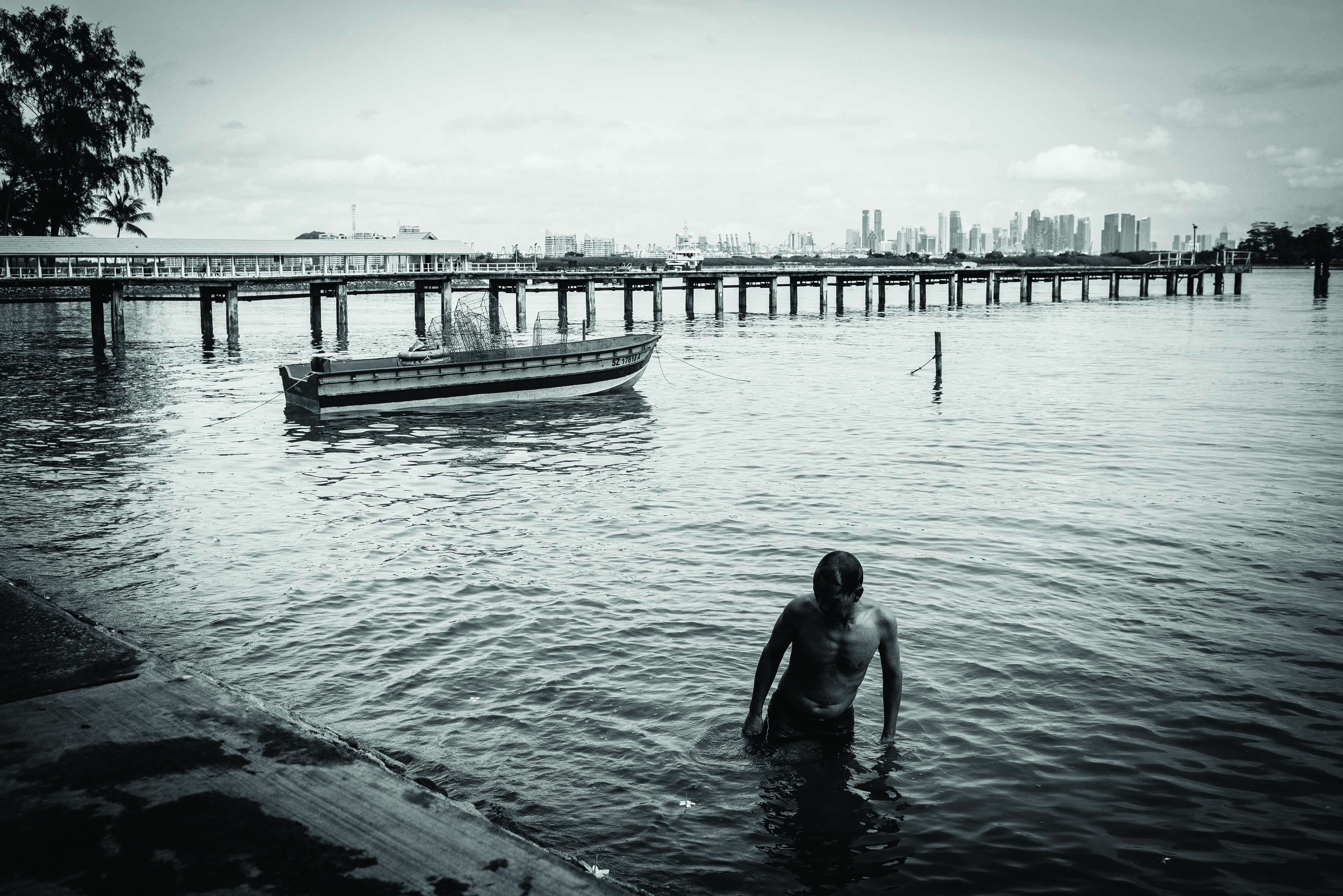

A man returning from his fishing trip on St John's Island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

A man returning from his fishing trip on St John's Island. Photo by Edwin Koo.

This project was supported by the Singapore Memory Project's (SMP) irememberSG Fund that aims to encourage organisations and individuals to develop content and initiatives that will collect, interpret, contextualise and showcase Singapore memories. The fund has currently stopped accepting applications. For more information, go to: http://www.iremember.sg/indexphp/fund-intro/

Zakaria Zaina is an associate photographer for Captured, a creative agency based in Singapore that specialises in delivering visual-centric narratives.

NOTES

-

The exhibition “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” was held at the National Museum of Singapore from June to August 2014. ↩