Culture on Celluloid: Alternative Films in Singapore

Intellectual and art house films have a long history in Singapore but the issues the genre faces have changed little over the years. Gracie Lee charts the challenges of alternative cinema in our city.

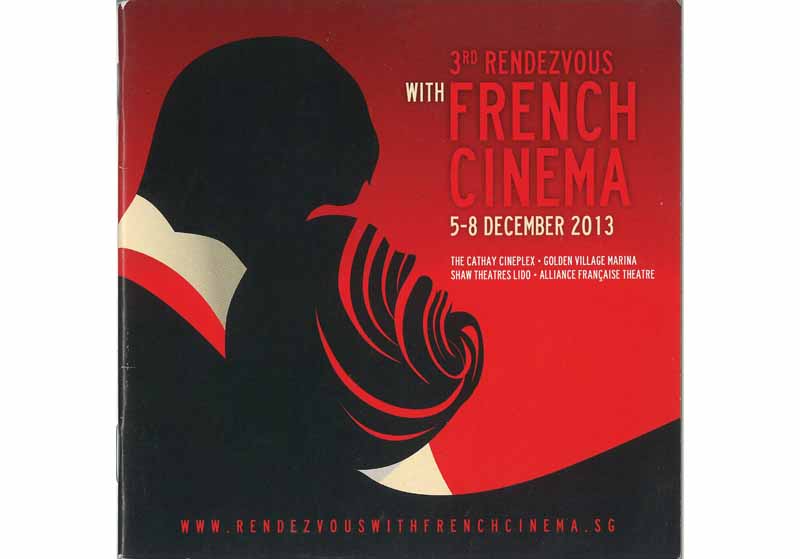

Publicity poster for the third French film festival – Rendezvous with French Cinema – in 2013. Collection of National Library, Singapore.

Publicity poster for the third French film festival – Rendezvous with French Cinema – in 2013. Collection of National Library, Singapore.

The beginnings of the art house cinema originated in France during the early 1920s in response to the growing commercialisation of films by Hollywood. After World War I, pioneering French film companies such as Gaumont and Pathé, which once dominated the European motion picture industry, began losing out to big budget Hollywood productions. In response, French producers began experimenting with new approaches to filmmaking, paving the way for the emergence of the French avant-garde film.

At the same time, an intellectual film culture took root in France, giving rise to the publication of film reviews in journals and newspapers, the establishment of specialist theatres and the proliferation of film societies called cine-clubs which held regular screenings of non-mainstream films such as art films, political films and retrospectives. Forums were also held for filmmakers and enthusiasts to meet and discuss the art of cinema. The cine-clubs were very successful and began to spread throughout Europe. In Britain, the London Film Society was established in 1925.

The Dominance of Hollywood

The allure of the cinematograph for mass entertainment was phenomenal, extending its global reach to Singapore. Movie-watching was such a popular past time in this British colony that it prompted a reader of the Malaya Tribune to declare the 1930s as the “Cinema Age”. 1 In 1929, a Straits Times editorial reported that “almost every small town in Malaya possesses its cinema”,2 and as early as 1917, an Eastern Kinematograph Association had been formed to protect the interests of exhibitors here. 3

By the 1930s, Hollywood had firmly entrenched its foothold in Singapore. Pre-war figures estimate that 70 percent of films shown in Singapore were American, 16 percent British and 13 percent Chinese, with the remaining from India, Java and Egypt. The stranglehold of American films was reinforced by the presence of major Hollywood distribution offices in Singapore, many of which were located along Orchard Road, including First-National (1926; later Warner Bros-First National), Fox Film (1927), United Artists (1928), Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (1929, reorganised as Paramount in 1931) and Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer (1933).

A Difficult Singapore Audience

In 1933, long-time Singapore resident Roland Braddell wrote that the Singaporean audience was an “extraordinarily difficult” one. “They either like a picture or they don’t; direction, technique, lighting, photography, and the finer points of acting mean nothing. The Asiatic taste makes or mars a picture, and the results are startling. Thus four gold medal pictures, Cimarron, Smilin’ Through, Strange Interlude, and Grand Hotel were failures, while that magnificent picture Farewell to Arms flopped so hard that you could hear it in China…On the other hand, Pleasure Cruise, an ordinary programme picture, made plenty. Comedy, music, and love interest are what the Asiatics appear to like, and anything historical leaves them cold… the greatest financial successes in Singapore so far have been Love Parade, Sunnyside Up, Tarzan, East of Borneo, and Samarang…” 4

One Straits Times headline quipped, Malayan movie-goers “prefer Tarzan to serious films”.5 The article went on to elaborate that audiences enjoyed action films, cowboy, Tarzan and serial features but films with lots of dialogue or psychological stories were not popular.

Cynics would say that little has changed today as far as the maturity of Singapore film audiences is concerned – the commercial and mainstream still rule over the art house.

Calls for a Film Society

Despite the grim picture, the influence of film societies and film appreciation in Europe was beginning to make its mark in Singapore. In 1933, The Straits Times carried a public notice that “proposed to form an Amateur Film Society in Singapore”6 though it is not known if any readers responded to the call. In 1936, another reader advocated the setting up of a film society, adding that “it is the only thing which will save (Singapore) from complete aesthetic stagnation”.7 This would give Singaporeans a chance to view European and Russian films that commercial exhibitors did not import, and which did not come under the heavy-handed cuts by the Official Censor.

The following year, The Straits Times published a scathing forum letter about the sorry state of film culture in Singapore. “Singapore wants to see intelligent films”, the writer opined, adding that “it is time the farce of denying Singapore cinemagoers intelligent films ceased. Censorship – which presents abnormal difficulties in Singapore – has robbed filmgoers here of seeing such fine films…because they were ‘unsuitable for Malayan audiences’. A Film Society is the only way out for those who regard films as an art, who want to see more than the commercial productions of Hollywood and Elstree [Britain’s equivalent of Hollywood].”8

The letter found popular support: One reader responded, “We are so surfeited with American films, that the ‘differentness’ of a good European picture is a refreshing experience. In a cosmopolitan city like Singapore, one would imagine that there would be a public for such as a film society.” Another said, “The plea…is a reminder of Singapore’s cultural anaemia”.9

While Singapore mulled over setting up a film society, Kuala Lumpur went ahead and formed the Malayan Film Society on 6 October 1947. The 120-member society was headed by Jack Evans, the newly appointed Film Censor for Malaya. Two of its objectives were “to afford members opportunities of seeing and discussing Indian, Chinese, and English films which might not normally be seen in public cinemas” and “to promote interest in the production of Malayan films.”10 In practice though, the society’s line-up comprised mainly European productions. Examples of films screened include The World is Rich (1947), a black-and-white British documentary on world food scarcity after World War II; The Magic Bow (1946), a British musical on the life of Italian composer Paganini; and acclaimed French film noir Quai des Orfevres (1947). By 1953, however, the society was no longer in existence. The vacuum was filled by the thriving Selangor Film Society, which had over 900 members at one point.

The Singapore Film Society

The official history of the Singapore Film Society (SFS) dates its beginnings to the expatriate community in 1958. However, newspaper sources point to a precursor of the film society in 1948 through the initiative of some like-minded locals. This earlier film society, also called the Singapore Film Society – presided by Tan Thoon Lip (Singapore’s first Asian registrar of the Supreme Court) with Lim Choo Sye as secretary – started with 50 members of different races and backgrounds, which later increased to 100. It aimed to “enable its members to see more specialised, historic, educational and artistic films than is possible in the ordinary cinema”,11 and to “(instil) a better appreciation of films in the large Singapore film-going public”.12 Modelled after film societies in Britain, SFS’ members paid a subscription of $20 to see 24 films a year.

The SFS’ first screening was held at Cathay Cinema and opened with three films: The World is Rich, a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) award winner and an Academy Award nominee for Best Documentary; The Centre; and Cyrus. Thereafter, the society held most of its screenings, comprising a repertoire of features, shorts, documentaries and cartoons, at the Victoria Theatre and the British Council Hall at Stamford Road. Its members were privy to films such as Girl of My Dreams (1944), a German wartime romance; Alexander Nevsky (1938); Walt Disney’s Bambi (1942); and Nasib (1949), a locally produced Malay film by the Shaw Brothers.

To enhance the appreciation of the films, the SFS organised talks to tie in with the films. For instance, at the screening of English Criminal Justice, the chief justice of Singapore, Sir Charles Murray-Aynsley spoke about the film and English law, while R.E. Holttum, Professor of Botany at the University of Malaya, was invited to speak at the screening of Story of Plant Life.

By 1950, however, the SFS was in dire financial difficulties. The high cost of hiring films, heavy entertainment tax, limited screening facilities, and difficulties in procuring films were crippling the society. Moreover, the society had to rely on the services of local distributors because it was not allowed to import films directly. As part of its cost-cutting measures, the society screened 16 mm films at members’ homes. Despite these valiant efforts, news about the society’s activities ceased around 1950, and it was clear that by 1953 the society was no longer functioning.

On 15 October 1954, however, efforts to revive a film society were mounted and a committee comprising mainly expatriates was formed with Eric Mottram as president. Mottram, who was a lecturer at the University of Malaya and later a key figure in Britain’s poetry revival of the 1960s, had a long association with film societies in Britain. The society began functioning again with 185 members to aid the “promotion and appreciation of good films among its members with membership open to people of all races”.13

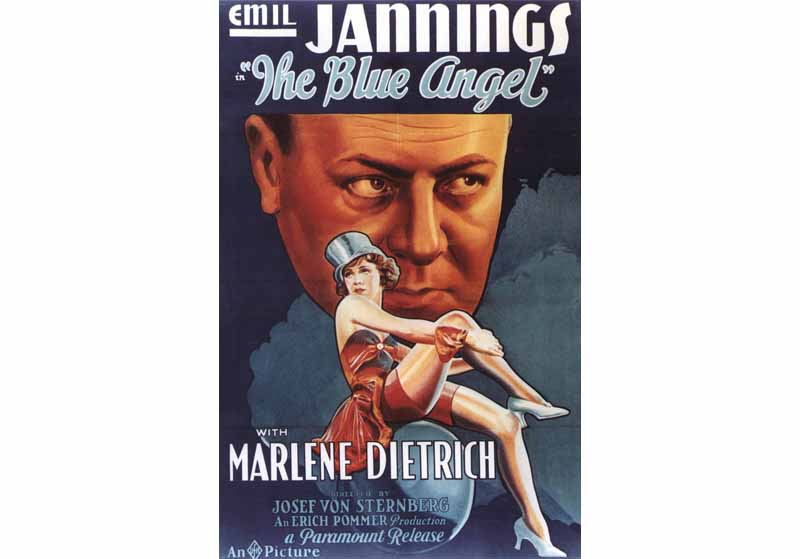

For its first presentation, The Blue Angel (1930) was screened at the British Council Hall. The movie, which propelled actress Marlene Dietrich into international stardom, traces the descent of a sanctimonious professor after he becomes entranced by Lola Lola, the headline act at a local cabaret called “The Blue Angel”. The tragicomedy is regarded as the first major German sound film and a fine showcase of German expressionism. SFS’ premiere screening played to a packed audience in Singapore. A hundred people had to be turned away at the door and a repeat screening was arranged.

The Blue Angel is one of the earliest art house films to be screened in Singapore. © The Blue Angel. Directed by Josef von Sternberg, produced by Erich Pommer, distributed by UFA Paramount Pictures, Weimar Republic, 1930.

The Blue Angel is one of the earliest art house films to be screened in Singapore. © The Blue Angel. Directed by Josef von Sternberg, produced by Erich Pommer, distributed by UFA Paramount Pictures, Weimar Republic, 1930.

Since its revival, the SFS has been pivotal in forging an alternative film culture in Singapore through its presentations of artistic and experimental films of merit. From the 1960s to 1980s, the society struggled to be in the black, faced with increased costs while trying to grow its membership base. Nonetheless, the society maintained its policy of creative and daring programming, leveraging on partnerships with foreign cultural institutions and commercial exhibitors to deliver a different cinematic experience for audiences. In 1984, the SFS and the Kelab Seni Filem Malaysia (Malaysia Film Society) became affiliates, allowing members from both sides to enjoy reciprocal benefits.

Today, the SFS holds over 200 screenings a year and 75 percent of its members are locals. It established its permanent home at GV Marina in 1996. In 2015, the society moved to GV Suntec when the Marina cineplex closed down. The society has been a strong proponent for film classification over censorship, which the government adopted in 1991. Through its consultancy services, the SFS also helps organisations to manage and promote their film events.

Foreign Cultural Institutions

Singapore’s alternative film culture also owes the early years of its development to the work of foreign cultural institutions such as the French Alliance Française (AF) and German Goethe-Institut. In its fledging years, the SFS would borrow films from foreign embassies and cultural institutions to keep costs down. These foreign institutions, which were keen to promote their country, would also stage film events and festivals as a form of cultural diplomacy and engage Singaporeans through their national cinema. Some of the earliest and longest-running film programmes were established by the AF and the Goethe-Institut.

When the Singapore branch of the AF opened on 13 April 1949, it marked its launch with a screening of La Symphonie Pastorale (1946), which won the Grand Prix award at the 1946 Cannes Film Festival. The film, based on a novella by Andre Gide, is a discomfiting tale of spiritual blindness, forbidden love and morality. Since its first screening, the AF has been tireless in its efforts to promote French cinema, maintaining a close connection with the local film industry since 1960s and putting together film festivals since the 1970s. Today, Dr Shaw Vee Meng, the chairman of Shaw Organisation, sits on the board of the AF as president. The AF continues to organise thematic film series and mini-festivals, as well as regular screenings at its 236-seat in-house theatre through its Ciné Club and Ciné Kids programmes.

Another noteworthy cultural body that has done much to advance film culture in Singapore is the Goethe-Institut, founded in Singapore in 1978. That same year, the institute organised a film festival based on German literature, opening with Faust, which was inspired by celebrated German writer Goethe’s play of the same name. The cultural centre also began free weekly screenings of German classics and films from the German New Cinema movement at the RELC Auditorium in the 1970s.

From 1980 to 1994, the Goethe-Institut screened its films at its 220-seat cinema at the Singapore Shopping Centre; this was a time when there were few screenings of non-mainstream movies in the city. The Goethe-Institut later held screenings at rented premises in Finlayson Green, and later at its own auditorium at Penang Road, with a line-up that included features, documentaries, video-art, experimental and animated films. In 2014, the Goethe-Institut moved to a conserved shophouse at Neil Road; due to limited space at its premises, film screenings are now organised at multiplexes or cultural organisations such as the National Museum of Singapore.

Special mention should also be made of the British Council, which staged one of the longest-running film showcases, the British Film Festival (from 1984 to 2004), in Singapore. The European Economic Community (today the European Union) also showcased Continental films from Britain, France, Germany, Netherlands, Denmark and Ireland to audiences in Singapore as early as 1977. These film festivals were well-attended.14

Today, film festivals are almost de rigueur channels of promotion for foreign embassies. A Business Times article in 2003 reported that 10 to 12 film festivals are organised each year with robust ticket sales of up to 95 percent.15 Some of the foreign festivals that regularly appear on the film festival calendar include the French, Italian, German, Japanese, European Union, Chinese and Korean film festivals. Country-themed festivals on Arab, Australian, Israeli, Latin American, New Zealand, Russian, Scandinavian and Southeast Asian cinema have also been organised by foreign cultural agencies, the SFS or the Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF).

Publicity poster of the 8th German Film Festival held in 2004. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Publicity poster of the 8th German Film Festival held in 2004. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

The Singapore International Film Festival

The Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF, formerly SIFF), which just celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2014, is also an important contributor to the alternative film scene since its launch in 1987. Its founder Geoffrey Malone, a Singapore-based Australian architect, saw similarities between the languishing Singapore film industry and its dismal Australian counterpart until the latter’s renaissance in the mid-1970s. Having been a part of the Australian New Wave, and a regular attendee of the Sydney Film Festival, he was inspired to start a film festival in Singapore. Modelled after the Mill Valley Film Festival in San Francisco that Malone visited in 1986, the SGIFF was formed to spur local film production and to develop an audience for non-mainstream films.

The festival’s first outing had a decidedly Western (and slightly commercial) bent due to the choice of its opening film The Name of the Rose (1986), a historical mystery starring Sean Connery and Christian Slater, and closing film The Mission (1986), which was headlined by Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons. However, by its second instalment, the SGIFF had begun to define and establish its niche in Asian cinema, having featured the works of the Chinese Fifth-Generation directors and a retrospective on the iconic Malay actor P. Ramlee.

In its successive editions, the festival built its reputation as a platform for the promotion of Singapore-made films through the screening of Singapore shorts, features, documentaries and iconic films from the Singapore studio era (1947–1972); as well as a launch pad for aspiring local filmmakers through its introduction of the Silver Screen Awards that recognises the Best Asian Feature and the Best Singapore Short Film. The SGIFF “stood at the cradle of Singapore’s film revival…It stimulated the country’s short and feature production, discovered its seminal filmmakers, and highlighted its neglected film history.”16

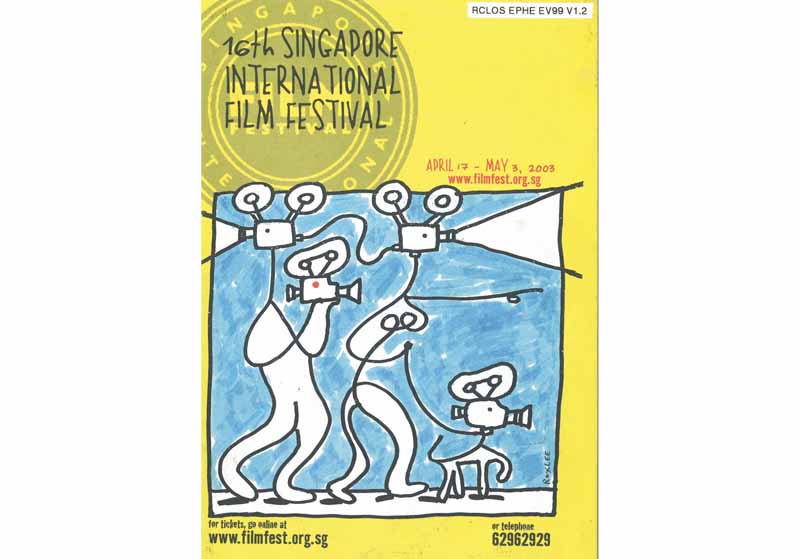

Publicity poster of the 16th Singapore International Film Festival in 2003. The SIFF was launched in 1987. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Publicity poster of the 16th Singapore International Film Festival in 2003. The SIFF was launched in 1987. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Art House Cinemas

With the groundwork laid by the SFS since the 1950s, foreign cultural institutions from the 1970s and the SGIFF in the 1980s, the market appeared ripe for the entry of commercial exhibitors in the 1990s. This decade saw the opening of several art house cinemas in quick succession: Cathay’s Picturehouse (November 1990), Overseas Movie’s Golden Studio (February 1991), Shaw’s Jade Classics (April 1991) and Lido Classics (June 1993).

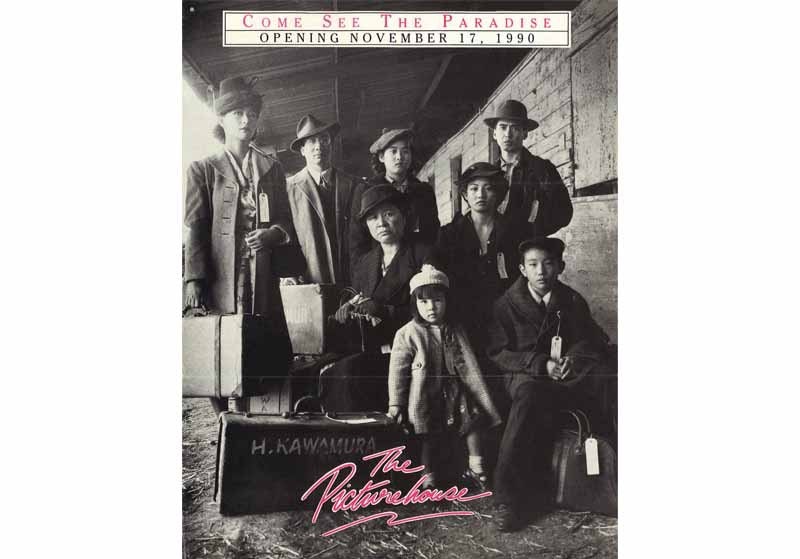

When Cathay Organisation opened Picturehouse, it had already assessed that audience tastes had changed and filmgoers were becoming more selective – in short Singapore was ready for an upmarket speciality cinema (Picturehouse was known for its draconian etiquette on dressing and food consumption that was implemented to enhance the art film viewing experience). The theatre screened critically acclaimed and independent films such as Come See The Paradise (1990), The Wedding Banquet (1993), Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995) and Underground (1995), which straddled between art and entertainment.

Come See the Paradise was the opening film for Picturehouse when it was launched in 1990. © Come See the Paradise. Directed by Alan Parker, produced by Robert F. Colesberry & Nellie Nugiel, distributed by 20th Century Fox. United States, 1990. Collection of National Library, Singapore.

Come See the Paradise was the opening film for Picturehouse when it was launched in 1990. © Come See the Paradise. Directed by Alan Parker, produced by Robert F. Colesberry & Nellie Nugiel, distributed by 20th Century Fox. United States, 1990. Collection of National Library, Singapore.

However, the cinema found that it could not survive on art films alone as local audiences were not quite ready for more alternative fare. The company began introducing mainstream films, such as Army Daze (1996), The Crow (1994) and Striptease (1996), alongside its less commercial offerings. In 2000, Picturehouse closed after a 10-year run when Cathay Building underwent a revamp. The cinema returned in 2006 with a smaller hall of 82 seats which allowed Cathay to experiment with more esoteric programming without the pressure of filling seats. In the same year, Golden Village introduced the speciality Cinema Europa at its newly opened multiplex at Vivocity.

Today, the outlook for permanent art house venues appears bleak. At present, only Picturehouse and Sinema Old School (Singapore’s first and only independent cinema that operated at Mount Sophia from 2007 to 2012) exist as brands as the industry contends with piracy and competes against online streaming, DVD releases and a host of mini film festivals.

Nonetheless, in January 2015 a new independent cinema, The Projector, opened at the old Golden Theatre at Golden Mile Tower. Its management, Pocket Projects, which specialises in adaptive re-use of historic spaces, has partnered FARM, a cross disciplinary design practice, to retain the original retro charm found in the venue’s steel frame seats, signage and floor lettering. Luna Films, a film consultancy company, has also been invited on board to curate and bring in alternative films.

Other Initiatives

Art and cultural centres with screening rooms have also contributed to the development of film appreciation in Singapore through the film series, festivals, talks, workshops, symposiums and filmmaking projects they organise. Some of the more well-known programmes include Moving Images by The Substation (1997), Screening Room by the Arts House (2004) and Cinematheque by the National Museum of Singapore (2006). Broadly, The Substation’s curatorial focus is on video art, experimental films, Singapore shorts, documentaries and regional works; the Screening Room showcases films from Singapore and Asia as well as cult favourites; while the National Museum’s emphasis is on Singapore shorts and retrospectives, and World Cinema.

To support the commercial and not-for-profit exhibition of alternative films, small independent film distributors such as Festive Films (2002), Lighthouse Pictures (2003) and Objectifs Film (2006) have emerged in recent years, as well as indie film websites such as Sinema and SINdie to challenge and whet the appetites of avid cinephiles in Singapore.

THE FIRST ART HOUSE CINEMA

Though Picturehouse is commonly thought to be the first commercial art house cinema in Singapore, Premier Cinema at Orchard Towers was an even earlier entrant to the scene. When it opened on 29 November 1978, the S$3-million mini-cinema had the smallest hall in town with 477 seats. Its highbacked seats, posh blue interior, and erudite programming soon made it a popular venue with the “arty film crowd”.17

In its early years, Premier Cinema was known for its release of quality films such as Australian director Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and works by Tsui Hark and Ann Hui, the auteurs of the Hong Kong New Wave Cinema. It was also a favoured venue for film festivals such as the ASEAN, Indian, French and German film festivals. At its peak, one of its films, The Hurricane (1979), remained in the box office for three months. However, it was a case of “too arty, too soon” as “most Singaporeans at that time hardly knew what art pictures were”.18 To remain financially viable, the cinema turned to screening B-grade flicks such as Gold Raiders (1982) and Hongkong slapsticks like Aces Go Places II (1983). Other conditions, such as restrictions on ticket prices, a 35 percent entertainment tax, poor economy and the boom of videos, took its toll on the cinema. Premier Cinema shut its doors in 1983, and was converted into a live-show theatre.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the ephemera collection, and developing and providing content and reference services relating to Singapore.

REFERENCES

Aitken, I. (2001). European film theory and cinema: A critical introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Braddell, R. (1982). The lights of Singapore. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BRA)

Burns, J. (2013). Cinema and society in the British empire, 1895–1940. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. (Call no.: RSING 302.234309171241 BUR)

Chua, A.L. (2012, December). Singapore’s ‘cinema-age’ of the 1930s: Hollywood and the shaping of Singapore modernity. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 13 (4), 592–604. (Call no.: R 306.095 IACS)

Drazen, C. (2011). The faber book of French cinema. London: Faber and Faber. (Call no.: 791.430944 DRA)

Duggal, U. (2014, December 13). New indie cinema The projector woos hipsters with original, retro seats and specially curated indie films. Retrieved from mothership.sg

Khun, A., & Westwell, G. (2012). A dictionary of film studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 791.4303 KUH)

Parkinson, C.N. (1951). Report of the committee on film censorship 1951. Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RCLOS 791.43 SIN; Microfilm no.: NL9938)

Sinema. (n.d.). SINdie. Retrieved from sinema.sg website.

Stevenson, R. (1974, September). Cinemas and censorship in colonial Malaya. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 5 (2), 209–224. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Tan, K.C.S. (1988). Cinema management in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Film Society. (Call no.: RSING 791.43068 TAN)

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore. Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD)

Notes

-

Chua, A.L. (2012, December). Singapore’s ‘cinema-age’ of the 1930s: Hollywood and the shaping of Singapore modernity. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 13 (4), 592–604, p. 592. ↩

-

The film in education. (1929, May 2). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Eastern kinematographs. (1917, March 13). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Braddell, R. (1982). The lights of Singapore (pp. 120–123). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BRA) ↩

-

They prefer Tarzan to serious films. (1948, July 13). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Public notices. (1933, August 28). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Film society for Singapore. (1936, December 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore wants to see intelligent films. (1937, May 23). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Intelligent films. (1937, May 30). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Film society for Malaya. (1947, October 6). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Blow at cultural desert charges. (1948, July 18). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Langdon, R. (1950, March 25). ‘Super’ films not Superman. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yuen, F. (1954, October 31). Is film society open to public? The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Saw, P.L. (1978, November 6). Film festival proves locals do care. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nayar, P., & Cheah, U. (2003, July 11). Beyond Hollywood. The Business Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore (p. 221). Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD) ↩

-

Leong, W.K. (1983, February 18). Premier cinema to become live show theatre. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Foo, J. (1990, November 18). Too arty, too soon. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩