From Tents to Picture Palaces: Early Singapore Cinema

Few people are aware that Singapore’s cinema history dates back to as early as 1896. Bonny Tan traces its development, from the days of the Magic Lantern projector to the first locally made films.

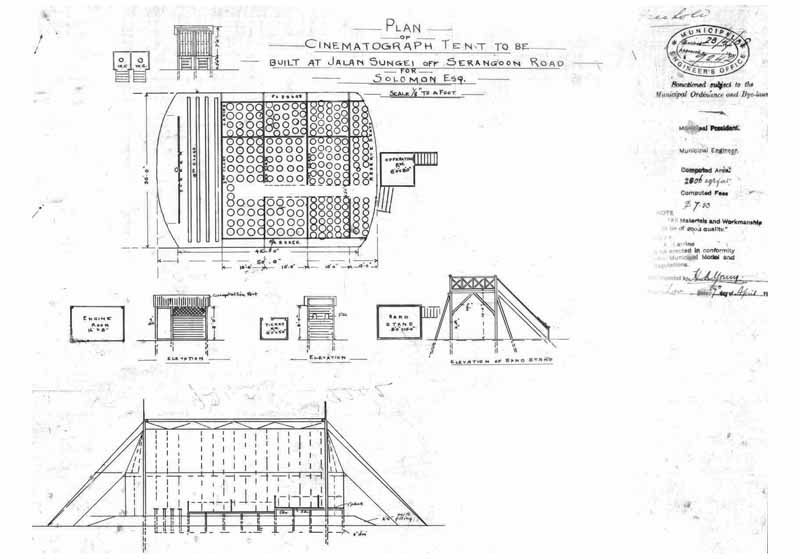

Plan of a cinematograph tent located at Jalan Sungei at Serangoon Road in 1908. Building Control Authority Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Plan of a cinematograph tent located at Jalan Sungei at Serangoon Road in 1908. Building Control Authority Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

“All we can say to Singapore’s pleasure-seekers is that if they do not like a couple of hours to hang heavily on their hands they could not do better than wend their steps to the Company’s tent after dinner and feast their eyes on this unique and novel exhibition.”

Singapore’s first public film screening is often mistakenly attributed to Basrai, a travelling Parsi impresario who is believed to have shown the movie in April 1902 in a tent pitched at the junction of Hill Street and River Valley Road.1 Archival newspaper reports, however, indicate that the April 1902 screening was organised by the American Biograph Company at the foot of Fort Canning along Hill Street.2 But the real story of Singapore’s film history movies predates this first public screening and is much richer than previously thought.

The First Film Experiences

When the cinema age descended on Singapore at the turn of the 19th century, its evening entertainment offerings were already varied. Europeans, dressed to the nines would head off for lavish dinner parties that continued past 9 pm.3 They would then either play a round of cards or proceed to a theatrical performance that stretched late into the night. Locals, on the other hand, would gather in open-air spaces to watch Chinese opera, Javanese wayang kulit (shadow puppetry), or sit in rapt attention to bangsawan, a dance, music and drama performance that drew from the cultural heritage of the Arabs and adapted European tales into the local Malay language.4

The predecessor of modern cinema was the Magic Lantern where images were projected and manipulated, either to tell a story or create an effect on stage. One of the earliest of such shows in Singapore was a phantasmagoria – which projected images of ghosts, spirits and other scary apparitions at the Theatre Royal by a Monsieur George in 1846.5 By the 1880s, Magic Lantern shows were regularly screened as entertainment for military families,6 in local churches for religious edification7 and in schools for education.8

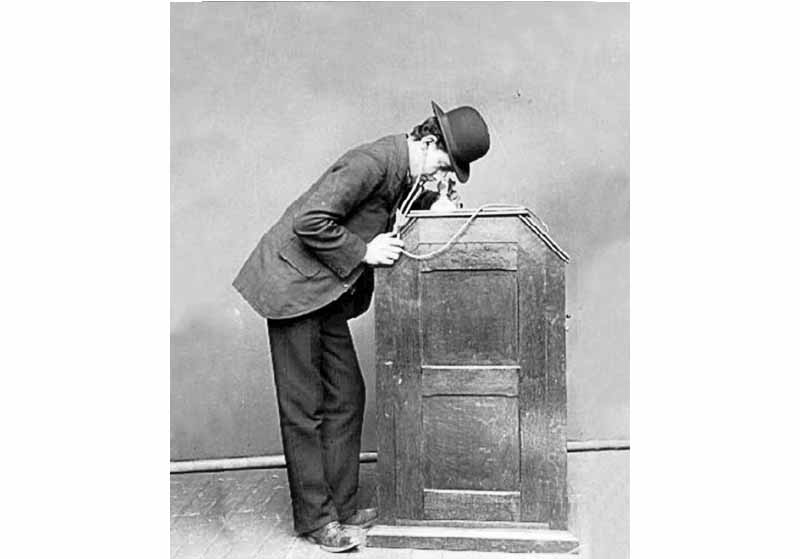

In 1896, the first experience of an animated image using American technology – the Kinetoscope – was brought to Singapore by Dr Harley, an illusionist. The Kinetoscope was a standing box where patrons, one at a time, could watch scenes ranging from dances to cock fights through a peephole viewer at the top of the box. Images were captured on celluloid and quickly run through a series of wheels by an electric motor, aided by an electric lamp shining through it, thus giving the impression of animation. Several Kinetoscope boxes were exhibited for several days in July 1896 at Messrs. Robinson’s music store for a limited number of people.9

Just a year later, in May 1897, the Ripograph, better known as the Giant Cinematograph, was brought from Paris by a man named Arthur Sullivan who boldly advertised that the 10,000-dollar equipment projected “the largest life pictures in the world”10 (it is likely that Sullivan exaggerated the cost and size of images for commercial advantage). This was less than two years after the first public screening of a movie in France by the Lumiere brothers in December 1895.11 The Ripograph was described as “a mechanical arrangement of instantaneous photographs taken at about twenty to forty exposures per second on a fine continuous film and from what could be seen, it gives a very accurate picture of animate existence. The pictures, projected by a magic lantern on to a screen in front of those present, give a natural appearance to the scenes depicted.”12

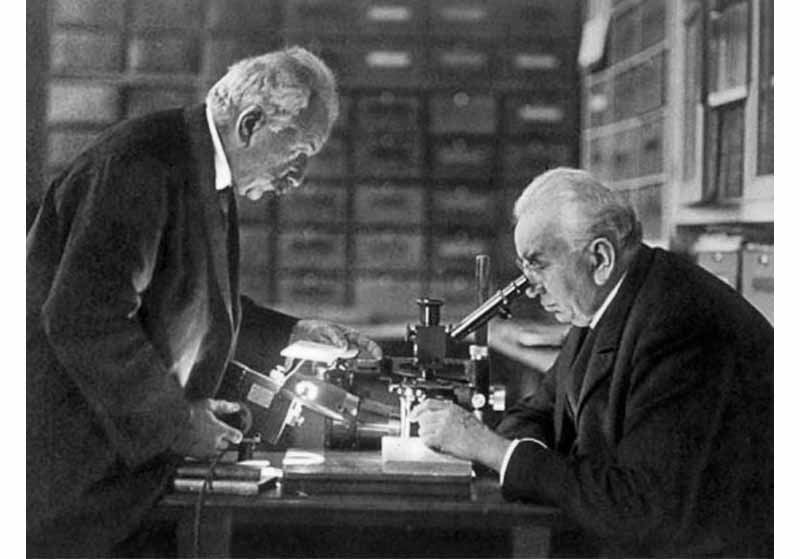

Meanwhile, new cinematographic inventions came fast and furious from the laboratories of Thomas Edison in America and the creative minds of the French, such as the Lumiere Brothers and Leon Bouly. The Cinematograph, the Bioscope, the Biograph, the Vitascope and the Projectoscope were introduced in quick succession – each touted to be better than the former.

A man watching a scene using the Kinetoscope. Via Wikimedia Commons.

A man watching a scene using the Kinetoscope. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The Serpentine Dance, a form of burlesque, was one of the first vignettes screened at the Aldephi Hall in 1897. © The Serpentine Dance. Directed by Louis Lumiere, produced by Lumiere. France, 1897.

The Serpentine Dance, a form of burlesque, was one of the first vignettes screened at the Aldephi Hall in 1897. © The Serpentine Dance. Directed by Louis Lumiere, produced by Lumiere. France, 1897.

Frenchmen August and Louis Lumiere were one of the first filmmakers in history. Via pixgood.com.

Frenchmen August and Louis Lumiere were one of the first filmmakers in history. Via pixgood.com.

These earliest screenings were attractive only because of their novelty factor. In retrospect, the long wait between each vignette, “the incessant flickering, and the large and frequent blotches of white that traversed the screen when …nearing what promised to be the most interesting part of the subject” detracted from the pleasure of the experience. 13 The developing technology was the cause of these discomforts in part, but the tropical weather was also a factor: “(f)licker and vibration visible on the screen were due to the effect of the moisture of the atmosphere causing the films to stick and run at times unevenly…”.14 Short live performances to keep the audience entertained served as fillers during technical glitches, a change in film or other delays. Eventually, as the technology improved, the films began to run more smoothly and were marked by fewer interruptions.

The Business of Early Cinema

The business, set-up and location of film-houses mirrored the trend set by circuses that were already doing their rounds at the time in Singapore and key cities of the Malay Peninsula, the Malay archipelago and beyond.15 Business entrepreneurs who saw the commercial potential of this new technology brought in reels of film with a large repertoire of shows. In Singapore, early cinema managers would pitch makeshift tents in the style of a circus, either on Beach Road or at the foot of Fort Canning Hill. One even billed itself as the “Barnum of Cinematographs”.16

Using tents gave flexibility to these set-ups as extra seats, for example, could easily be brought in from nearby hotels or patrons could stand in between chairs.17 These tents were far from makeshift: Matsuo’s Japanese Cinematograph along Beach Road was commended for its tent decorations as well as its ventilation and lighting.18 Not to be outdone, the tent next to it, the London Chronograph, was described as “fitted with electric lights and fans; the seating accommodation is good, special attention having been paid to the comfort of anticipated patrons.”19

Existing stage halls and music rooms also served as prime locations for screenings. These included the Adelphi Hall, which was part of the Adelphi Hotel at Coleman Street, and the Town Hall at Empress Place (which was later rebuilt as Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall). Some of the earliest movies were screened at these venues. In 1897, daily screenings at the Adelphi Hall included vignettes such as The Charge of Lancers, The Serpentine Dance and Li Hung-Chang in Paris, with admission costing 50 cents for back-row seats and $1 for front seats.20

Some hotels, in fact, modified their structures to allow for the screening of movies, such as the Raffles Hotel, which in June 1908 converted its Billiard Hall to a Music Hall to screen films by Edison Studios, a film production company founded by the inventor Thomas Edison.21 These sophisticated locations charged higher entrance fees and invariably attracted the upper echelons of society. In 1908, the Raffles Hotel immediately raised its ticket price to $2 after the success of their first screening – Ben Hur.22

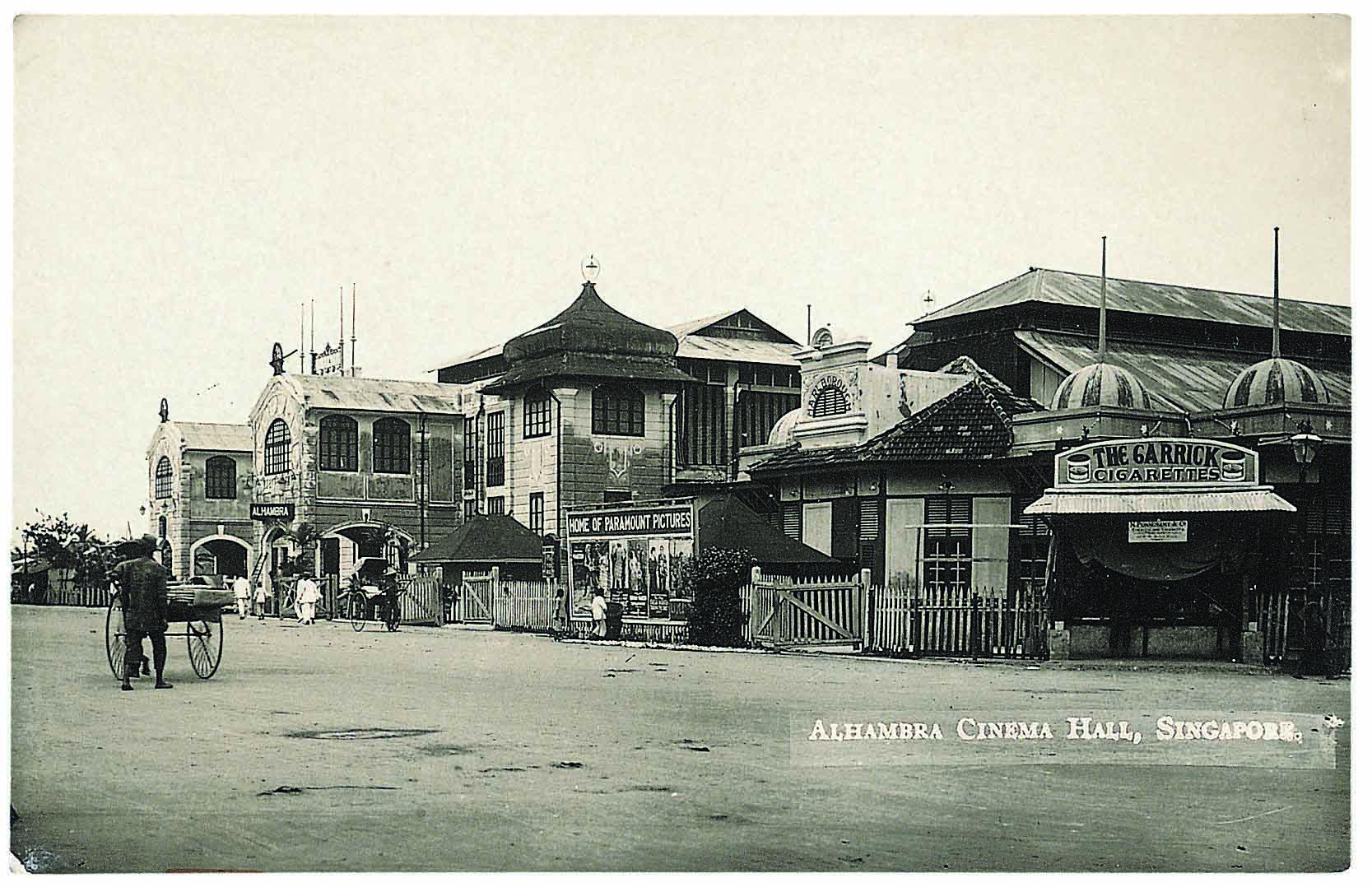

In its earliest years, the business of cinematography was tenuous and the management of these tents and halls frequently changed hands. However, as cinema’s popularity – and financial returns – grew, the tents soon gave way to simple constructed halls and, subsequently, to more elaborately designed “picture palaces”. French entrepreneur Paul Picard, with support from jewellers Levy Hermanos, is often credited for opening the first enclosed cinema in Singapore in 1904, the Paris Cinematograph, which occupied a section rented from the Malay Theatre on Victoria Street.23 Other larger cinema halls soon sprouted, including the Alhambra (1907) and Marlborough (1909) along Beach Road and the Palladium (1914) on Orchard Road.24

The early entertainment empire builder before the advent of Shaw and Cathay was Tan Cheng Kee, the eldest son of pioneer business leader Tan Keong Saik. He not only invested in the key theatres – the Alhambra, the Marlborough and the Palladium Cinema – but also revamped their decor and worked out a sound business strategy.25

Tan engaged artist W.J. Watson to add colour and grandeur to the proscenium of the Alhambra. Painted in opal blue, amethyst, gold orange and crimson, it had “ten flags of the leading nations group round an architectural arch and pediment enclosing the screen. The wreathed bust of Shakespeare (was) in the centre over the word ‘Alhambra’, surrounded by roses.”26

In 1916, the Alhambra was rebuilt and renamed the New Alhambra. Designed by Eurasian architect Johannes Bartholomew (Birch) Westerhout, the New Alhambra accommodated an audience of 1,500 with a variety of seats, including special box seats, each holding comfortable armchairs, and a specially designated box for members of the Malay royalty. Other lavish details included “costly curtains” that draped down the stage doors, a “beautifully tiled floor”, electric lights, large mirrors and a private telephone booth. 27

Tan paid $25,000 for the Palladium (also designed by J.B. Westerhout) a mere four years after it was built.28 This was a steal considering it had cost $60,000 to construct. Tan continued to push the envelope with the development of local cinemas, fitting them in 1930 with equipment for sound so that the first “talkies” could be screened.29

Adelphi Hotel on Coleman Street, as seen in a 1906 postcard. Adelphi Hall, where Singapore’s earliest film screenings were held in 1897, was part of the hotel. Arshak C Galstaun Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Adelphi Hotel on Coleman Street, as seen in a 1906 postcard. Adelphi Hall, where Singapore’s earliest film screenings were held in 1897, was part of the hotel. Arshak C Galstaun Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

A 1930 postcard of the Alhambra cinema along Beach Road. Taken from the book Singapore: 500 Early Postcards, published by Editions Didier Millet (2007). Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.

A 1930 postcard of the Alhambra cinema along Beach Road. Taken from the book Singapore: 500 Early Postcards, published by Editions Didier Millet (2007). Courtesy of Prof Cheah Jin Seng.

Malaya in Early Films

A great variety of shows were screened in Singapore’s early cinemas – from street processions to snippets of life in Malaya. From as early as 1897, short films such as The Jubilee Procession in London which commemorated the British Queen’s reign and the British Empire’s rule, were frequently featured.30 What is less known is that since the earliest screening of film in Singapore, aspects of Malaya and the region have been featured in these seedling productions. M. Talbot, one of the first to film the wonders of “Malay Native life”, screened his production of boys bathing in a river in Batavia and elegant Javanese dancing girls at the Adelphi Hall in 1898.31 This film was subsequently exhibited in Bangkok to rave reviews.32

By this time, local cinemas were regularly screening films showing snippets of life in the region, such as Singapore Harbour, Scenes in Batavia, Malay Dancing and FMS Railway. Harold Mease Lomas was one such cameraman who took extensive “living pictures” of North Borneo in 1903, 1904 and 1908 while working for the Urban Bioscope Company.33 These films of Borneo “must have been secured at great labour and expense, if not danger, and excellently portray conditions among the wilder Malay tribes of that great island”.34

By 1907, film distribution had moved from the hands of itinerant businessmen importing American and European films. Singapore had become a distribution centre of films in the region, with French company Pathé Freres as a key anchor.35 This transformed the ease with which films could be obtained, the scale in which they were shown and the variety of films that could be screened.

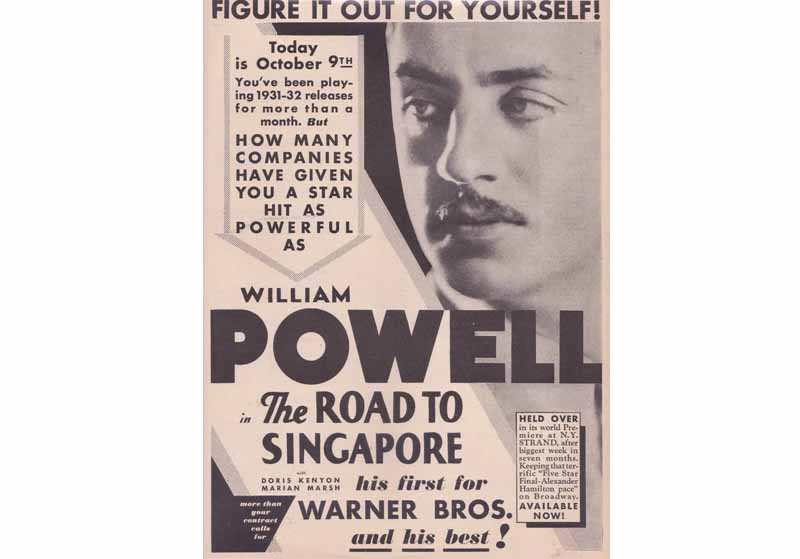

The Road to Singapore (1931) is a romantic drama starring William Powell and Doris Kenyou. © The Road to Singapore. Directed by Alfred E. Green, produced and distributed by Warner Bros. United States, 1931. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

The Road to Singapore (1931) is a romantic drama starring William Powell and Doris Kenyou. © The Road to Singapore. Directed by Alfred E. Green, produced and distributed by Warner Bros. United States, 1931. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

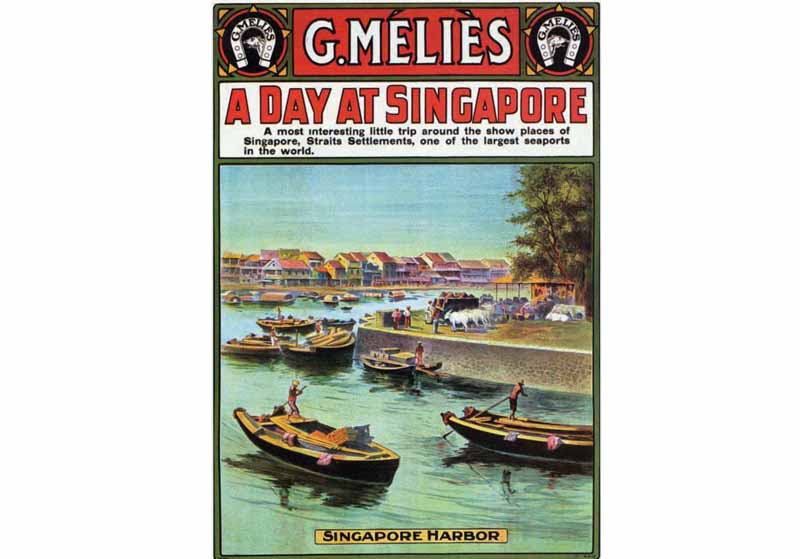

A Day at Singapore featured short snippets of life in Singapore. © A Day at Singapore. Directed by George Méliès, 1913.

A Day at Singapore featured short snippets of life in Singapore. © A Day at Singapore. Directed by George Méliès, 1913.

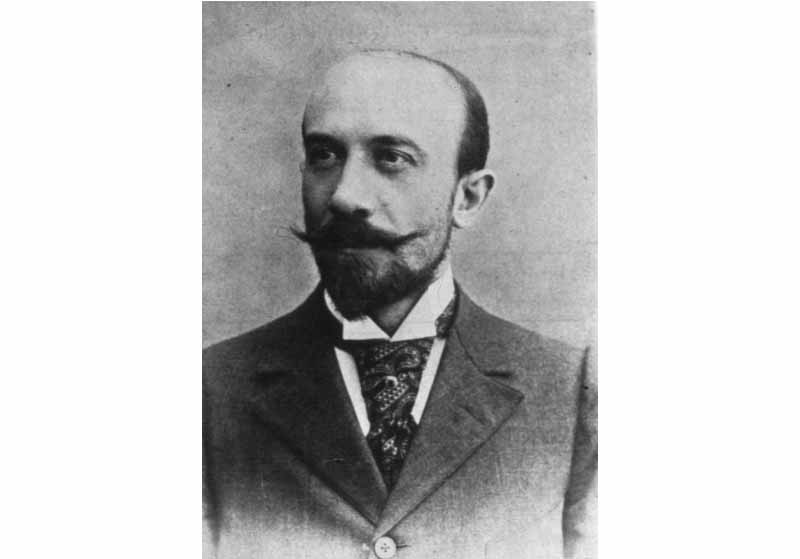

George Méliès (1861–1938) was a French illusionist and filmmaker. Via Wikimedia Commons.

George Méliès (1861–1938) was a French illusionist and filmmaker. Via Wikimedia Commons.

News documentaries became a regular feature in the cinemas when The Animated Gazette, produced by Pathé Freres, was broadcast weekly at the Alhambra in 1910.36 Singapore’s port and seascapes were often filmed, sometimes as standalone featurettes, like the 1910 Pathé film, Singapore, or as short vignettes, such as A Day at Singapore by Georges Méliès, which showcased “a most interesting little trip…to see one of the largest seaports in the world”.37 Méliès was world renowned for his fantastical movies using special effects such as A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904). His film on Singapore was made during his travels through the South Pacific and Asia between 1912 and 1913. It is uncertain if these short films were ever screened in Singapore, though they were certainly shown in other countries.

While narrative films featuring Singapore came out of then-budding Hollywood soon after, they were often only Singaporean in name; these films were not shot on location in Singapore, and worse, rarely featured Asian actors. These include MGM’s Across to Singapore (1928) starring Joan Crawford and Ramon Novarro, Sal of Singapore (1928) produced by Howard Higgin, The Crimson City (1928, also known as La Schiava di Singapore) starring Myrna Loy and Anna May Wong, The Road to Singapore (1931) shot by Alfred E. Green, and between 1923 and 1933, Out of Singapore directed by Charles Hutchinson and Malay Nights (also known as Shadows of Singapore).38

The 1933 film Samarang, styled as a pseudo-documentary (only to allow some nudity), is likely the earliest Hollywood feature film to be shot in Singapore. However, it was the Singapore-made vernacular films Xin Ke ( 新客, The Immigrant, 1927) and Leila Majnun (1934) that made a bigger impact on the local film scene. These productions were produced by Asians, featured an Asian cast and carried authentic storylines. These films made set the scene for the flourishing of the Malayan film industry in the 1950s.

THE FIRST MADE-IN-SINGAPORE FILMS

Samarang

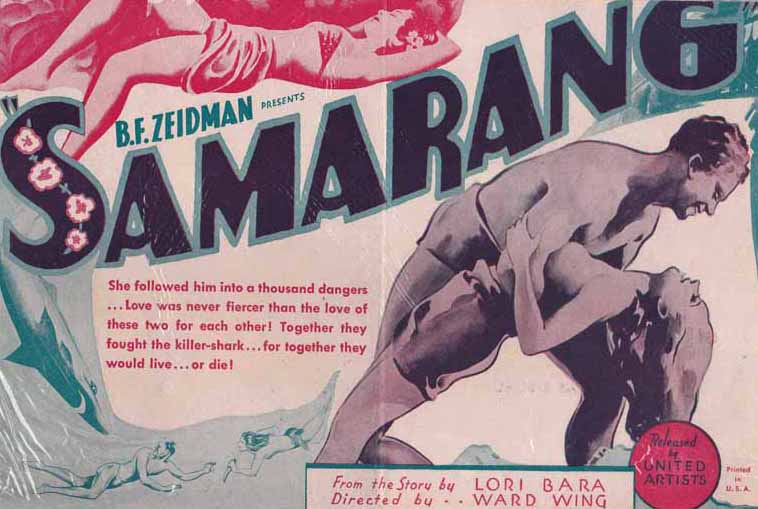

Released in 1933 and shot off the coast of Katong in 1932, Samarang (also known as Semarang, Out of the Sea and Shark Woman) is probably Hollywood’s first production to be filmed entirely in Singapore. Samarang recounts the romance between a pearl fisherman and a local chieftan’s daughter with cannibals, sharks and a python thrown in for good measure. It was produced by United Artists and B.F. Zeidman, directed by Ward Wing and written by Lori Bara.39

Samarang is the first Hollywood film about Singapore where the lead actors were locals, with Capt. A.V. Cockle playing the role of Ahmang, the North Bornean Dayak hero, and Theresa Seth as Sai-Yu, the Chinese beauty. Although both actors lived in Singapore, they were not of Asian descent – Cockle, from Britain, was an Inspector of Police based here and Seth was the daughter of an Armenian businessman who had settled in Singapore.40 The leads were obviously chosen for their telegenic looks: Cockle had the brawny physique of a swimmer and Seth was a beauty pageant contestant. Several locals, many of whom were experienced bangsawan actors, undertook bit parts while much of the kampong scenes featured its own local residents.41

Samarang was screened in the US in 1933 to rave reviews. The film’s popularity might have been due to its novelty but also possibly because Sai-Yu is topless for most of the second half of the film. It was first screened at the Alhambra in September 1933 and later at the Marlborough in 1934, where it was hailed as Singapore’s first talkie42 – although reviewers noted that it was “virtually a silent film except for a synchronized music score and occasional choral singing. The action (was) explained by subtitles, and although there (were) melodramatic episodes, they (were) for the most part set forth with… little skill.”43

Poster of Samarang. © Samarang. Directed by Ward Wing, produced by United Artists and B.F. Zeidman, distributed by United Artists. United States, 1933. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

Poster of Samarang. © Samarang. Directed by Ward Wing, produced by United Artists and B.F. Zeidman, distributed by United Artists. United States, 1933. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

Xin Ke (新客, The New Immigrant)

Produced by Liu Beijin, 新客 (Xin Ke; The New Immigrant, 1927) is believed to be the first Chinese feature film that was completely shot in Singapore and Malaya. Of Fujian origins, Liu (1902–1959) was born in Singapore but grew up in Muar, Johor. Although inspired by the booming Shanghainese movie industry, he felt slighted as an overseas Chinese when he visited China in December 1925.

When Liu returned home three months later, he was inspired to produce Xin Ke, a melodrama about a newly arrived Chinese in Singapore, in part to convey the social struggles and issues facing the immigrant Chinese. Liu also hoped to revive an interest in Chinese culture among the Chinese community in Singapore, while depicting the life of an overseas Chinese to the Chinese in China.

Working from a rented house at 58 Meyer Road that served as a studio, staff dormitory and film processing room, Liu purchased French-made cinematographic equipment and auditioned more than 100 prospective actors for his film.

The scenes were shot at the Botanic Gardens in Singapore and the interiors of 58 Meyer Road, as well as across the causeway in rubber plantations and at the Sultan of Johor’s palace. Production ended in February 1927 and in the following month, the film had its test screening at Victoria Theatre.

By 7pm on the day of the test screening, more than 100 people were already waiting in line for the free tickets that were given out at the entrance of Victoria Theatre and by the time the film started, the 500-seat theatre was full. The black-and-white silent film totalled nine reels and was accompanied by both Chinese and English subtitles.

Xin Ke is unique because many local films produced thereafter were in Malay. It wasn’t until almost two decades later in July 1946 that a major production in Chinese made its appearance in Singapore with the release of Blood and Tears of Overseas Chinese (华侨 血泪) by China Film Studio. Soon after its premier in Singapore, Xin Ke was released in Hong Kong as Tang Shan Lai Ke (唐山來客). Xin Ke was the only film that Liu released, and unfortunately the original reels are no longer extant.

Leila Majnun

Leila Majnun (1934) is the first Malay language feature film produced in Singapore. The film is a tragedy in the vein of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet with elements of the Arabian One Thousand and One Nights. The plot centres on two lovers, Leila and Majnun, whose love is forbidden due to social conventions. Majnun is driven to despair and madness, thus living up to his name Majnun, which means “madness” in Arabic.

In the 1930s, Rai Bahadur Seth Hurdutroy Motilal Chamria of Calcutta began distributing made-in-India films in Singapore. In 1932, his Urdu version of Leila Majnun met with such success in Bombay that he was inspired to produce a Singapore version. Bardar Singh Rajhans, who had already produced two films in India, moved from Calcutta to Singapore to direct the film, which cost $5,000 to produce. After the war, Rajhans continued to shape the local Malay film industry by directing several other significant films.

The role of Leila was played by popular local star Fatima binti Jasman, a singer with HMV Records, while Syed Ali bin Mansoor, a well-known bangsawan stage actor acted as Majnun.

The film’s gala opening was held on March 1934 at the Marlborough. The dialogue was in classical Malay and the film was much praised although there were criticisms over the technical quality of the pictures. In 1962, B. N. Rao, by then an established director, remade this movie as Laila Majnun.

Bonny Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. Her interest in the history of films was sparked after she uncovered little known facets of colonial life in early newspapers of Singapore. She would like to thank Nadi Tofighian for his help in reviewing this article.

REFERENCES

Chearavanont, N., Au, H., & Ou, C.S. (2013). Film stories: Bangkok, Hong Kong, Singapore, Canton, San Francisco. Thailand: H. M. Ou. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Chearavanont, N., Au, H., & Ou, C.S. (2014). Movie stories. Hong Kong: H. M. Ou. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43095125 CHE)

Hang Tuah Arshad. [2004–2007]. Malay movies: Select movie leaflets. Kuala Lumpur: Meoral Publishing House. (Call no.: RSEA 791.4309595 MAL)

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E. & Braddell, R.St.J. (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2; pp. 477–478). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE)

Millet, R. (2006). Singapore cinema. Singapore Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL)

Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An illustrated history, 1819-today. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 305.84105957 PIL)

Tan, S.B. (1997). Bangsawan: A social and stylistic history of popular Malay opera. Penang: The Asian Centre. (Call no.: RSEA 782.1095951 TAN)

Tofighian, N. (2013). Blurring the colonial binary-turn-of-the-century transnational entertainment in Southeast Asia. Stockholm: Acta Universitatis Stockholmeinsis. (Call no.: RART 791.430959 TOF)

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore. Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD)

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y. N. (2013, April–June). The Immigrant: Singapore’s first feature (p. 37). Cinemateque. Singapore: National Museum of Singapore. Retrieved from Usma Ismail Academia website.

Van der Heide, W. (2002). Malaysian cinema, Asian film: Border crossings and national cultures (p. 126). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43 VAN)

Zamberi A. Malek & Aimi Jarr. (2005). Malaysian films: The beginning. Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD)

NOTES

-

Millet, R. (2006). Singapore cinema (p. 16). Singapore Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL); Thirty years of film entertainment. (1932, January 2). The Singapore Free Press, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Busrai is likely a reference to Messrs Busrai Co. a company dealing with unique products such as the Perpetual Pencil and the Dragon Pen. They were also owners of the Royal Bioscope which screened movies at a Beach Road tent at the end of 1902. The screening moved to the Hill Street location only on 10 January 1903. Page 2 Advertisements Column 3:The American Biograph. (1902, April 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2; Page 4 Advertisements Column 1: The American Biograph. (1902, April 23). The Straits Times, p. 4; Page 5 Advertisements Colum 3. (1902, October 17). The Straits Times , p. 5; Untitled. (1903, January 10). The Straits Times , p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E. & Braddell, R.St.J. (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2; pp. 477–478). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE) ↩

-

Tan, S.B. (1997). Bangsawan: A social and stylistic history of popular Malay opera (pp. 26, 35). Penang: The Asian Centre. (Call no.: RSEA 782.1095951 TAN) ↩

-

The Singapore: Saturday, Nov. 28th 1846 (1846, November 28). The Straits Times , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1883, February 5). The Straits Times , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Local and general. (1887, July 13). Straits Times Weekly Issue , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Magic Lantern entertainment. (1895, August 23). The Mid-Day Herald , p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Edison’s kinetoscope. (1896, July 13). The Straits Times , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 2: The Ripograph. (1897, May 20). The Straits Times , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore (p. 2). Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD) ↩

-

The Ripograph. (1897, May 13). The Straits Times , p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

R.A.S. (1914, March 10). The cinematograph of the East. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 1. Retrieved form NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The cinematograph. (1898, February 16). The Singapore Free Press , p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tofighian in his thesis expands on this further. Tofighian, N. (2013). Blurring the colonial binary-turn-of-the-century transnational entertainment in Southeast Asia. Stockholm: Acta Universitatis Stockholmeinsis. (Call no.: RART 791.430959 TOF) ↩

-

Page 3 Advertisements Column 1. (1906, May 21). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. (P.T. Barnum was the American showman and businessman who founded the Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1875.) ↩

-

The grand cinematograph. (1907, September 2). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 3; Royal cinematograph. (1906, September 3). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1906, June 14). The Straits Times, p. 8; The Japanese cinematograph. (1906, June 6). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The London chronograph show. (1906, May 28). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 May 1897, p. 2. ↩

-

Page 8 Advertisements Column 3: Raffles Hotel. (1908, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 8; Untitled. (1908, June 5). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ben Hur at Raffles. (1908, June 8). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An illustrated history, 1819-today (p. 100). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 305.84105957 PIL) ↩

-

Cinema has colourful history in Singapore. (1938, July 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Talkie” invasion. (1929, December 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 11; Talkies in Singapore. (1930, April 19). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1914, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The New Alhambra. (1916, January 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1918, May 1). The Straits Times, p. 8: Modern entertainment. (1913, December 24). The Singapore Free Press, p. 412; The Palladium Theatre. (1913, September 24). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Apr 1930, p. 12. ↩

-

Tofighian, 2013, p. 221. The Projectoscope. (1897, August 19). The Straits Times, p. 2; Page 2 Advertisement Column 2: The Jubilee Procession. (1897, August 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2; Page 1 Advertisements Column 3: The Jubilee Procession. (1897, August 24). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; Page 2 Advertisements Column 3: The Jubilee Procession. (1897, September 6). The Straits Times, p. 2; Page 2 Advertisements Column 3: The Jubilee Procession. (1897, September 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; The Projectorscope. (1897, September 14). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The scenimatograph. (1898, January 20). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 4. (1898, January 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Tofighian, 2013, p. 80. ↩

-

Tofighian, 2013, pp. 212–213; Page 1 Advertisements Column 1. (1903, October 20). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Japanese cinematograph. (1906, November 6). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Latest in cinematography. (1910, July 21). The Straits Times, p. 6 Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Melies, D. (1913, September 4). A day at Singapore. IMDB. Retrieved from IMDD.com website; On cinema. (2009, February 16). bithiam. Retrieved from bthiam.wordpress.com. ↩

-

“Out of the sea” off Singapore. (1932, October 9). The Straits Times, p. 9; The camera men are coming! (1933, June 18). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hu Ping. (2014). Of lost kampongs, fishnet bondage and remnant tombs in an equatorial Hollywood. Sgfilmhunter. Retrieved from sgfilmhunter.wordpress.com. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 9 Oct 1932, p. 9; Samarang/Shark Woman. Sgfilmhunter. Retrieved from sgfilmhunter.wordpress.com. ↩

-

Page 8 Advertisements Column 1: Samarang. (1933, October 1). The Straits Times, p. 8; The Alhambra. (1933, September 30). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9; Page 9 Advertisements Column 2: Alhambra. (1934, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hall, M. (1933, June 29). Samarang. The New York Times. Retrieved from New York Times website. ↩