The Golden Age of Malay Cinema: 1947–1972

Few people are aware that Singapore was once the hub for Malay filmmaking in Southeast Asia. Nor Afidah Bte Abd Rahman and Michelle Heng recount its fabled history.

Maria Menado as the pontianak in B.N. Rao's 1957 Dendam Pontianak. © Dendam Pontianak. Directed by B. Narayan Rao, produced by Cathay-Keris Films. Singapore, 1957.

Maria Menado as the pontianak in B.N. Rao's 1957 Dendam Pontianak. © Dendam Pontianak. Directed by B. Narayan Rao, produced by Cathay-Keris Films. Singapore, 1957.

Azizah, the alluring customer-turned-love-interest of trishaw-rider Amran (played by screen legend P. Ramlee) visits his run-down hut for the first time in Penarek Becha (1955). When Amran bemoans his humble station in life, she delivers a sagely line in return, “Tuhan tidak akan memberi sahaja kalau manusia tidak berusaha (God won’t just help people unless they make an effort).”1 The audience watches with bated breath as this beauty-with-brains helps her humble beau make a success of his life. Azizah (played by the sweetheart of Malay movies, Sa’adiah) vows to help him attend night school. This turns out to be just the kind of push an honest-but-poor trishaw rider needs to scale the rigid social ladder of the time and seek the blessings of her parents. For cinema audiences, the film’s central theme – the rejection of inequality through the pursuit of education – was a timely reminder of the need for self-reliance:2 Malaya was in the midst of agitating for independence from her British colonial administrators.

Penarek Becha (The Trishaw Puller) was a major box office hit when it was released in 1955 and was a watershed film3 for both its actor-director, P. Ramlee – the multi-hyphenate Renaissance Man of the Malay silver screen – as well as the local film industry. The success of this film paved the way for other Malays to direct films that suited the community’s sensibilities and ignited far-reaching changes in the screen image of the modern Malay and his struggle to come to terms with a rapidly changing world.4

Shaw Brothers vs Cathay-Keris

The winds of change, as far as post-World War II domestic film production was concerned, had already swept through Singapore with the 1947 release of the first post-war Malay film, Seruan Merdeka (The Call For Freedom),5 produced by S.M. Chisty of Malayan Arts Productions, and directed by the influential Calcutta-born auteur, B.S. Rajhans, who was also the director of the first Malay-language film in Singapore, Laila Majnun (1934).6 Starring Salleh Ghani and Siti Tanjung Perak, Seruan Merdeka focused on how young Malay and Chinese Singaporeans came together to resist the Japanese occupiers. It was a rare screen outing as it was unusual to see both Malay and Chinese actors on the screen. Although the film was a commercial failure due to a lack of cinemas, and consequently, limited exposure, Seruan Merdeka7 marked the start of what was to become the 25-year-long golden age of Malay cinema in Singapore.8

Shortly after World War II, Shaw Brothers reopened their film production studios at 8 Jalan Ampas, which had closed during the Japanese Occupation. In a shrewd business move, Shaw Brothers started Malay Film Productions (MFP) Ltd in order to tailor-make movies for the growing number of Malay film-buffs in Singapore and Malaya, which at the time was the most rapidly expanding regional market.9 Adopting the lucrative, vertically-integrated models of Hollywood studios such as MGM and Paramount, Shaw enjoyed an almost unrivalled monopoly of the Malay film industry. Between 1947 and 1952 alone, the prolific MFP produced 37 feature films, the first of which was B.S. Rajhan’s Singapura Di Waktu Malam (1947, Singapore Night).10

While the Shaws’ pre-World War II Malay films featured bangsawan actors and were helmed by Chinese directors including Hou Yao and Wan Hoi Ling, MFP’s stable of experienced Indian directors brought in from the subcontinent ensured a steady flow of Indian-influenced films with ‘overstylised’ acting as well as song and dance sequences.11 Certain cultural barriers, however, proved difficult to overcome as the direct translation of movie plots, dialogues and style carried over from Indian films caused rifts between foreign and homegrown talents at MFP.12

At this point, Rajhans recognised the need to infuse his crew with fresh blood instead of relying solely on the local traditional bangsawan (Malay opera) performers who had crossed over into the world of moving pictures. Whilst on talent-scouting trips in the Malay Peninsular and Singapore, Rajhans spotted the young musician P. Ramlee and quickly hired the charismatic singer-actor. Ramlee made his screen debut in the 1948 film Chinta (Love), playing the supporting role of a swarthy villain opposite screen siren Siput Sarawak.13

P. Ramlee was an actor-singer who starred in many of Shaw's MFP's films. © 120 Malay Movies, Amir Muhammad, published by Matahari Books, 2010.

P. Ramlee was an actor-singer who starred in many of Shaw's MFP's films. © 120 Malay Movies, Amir Muhammad, published by Matahari Books, 2010.

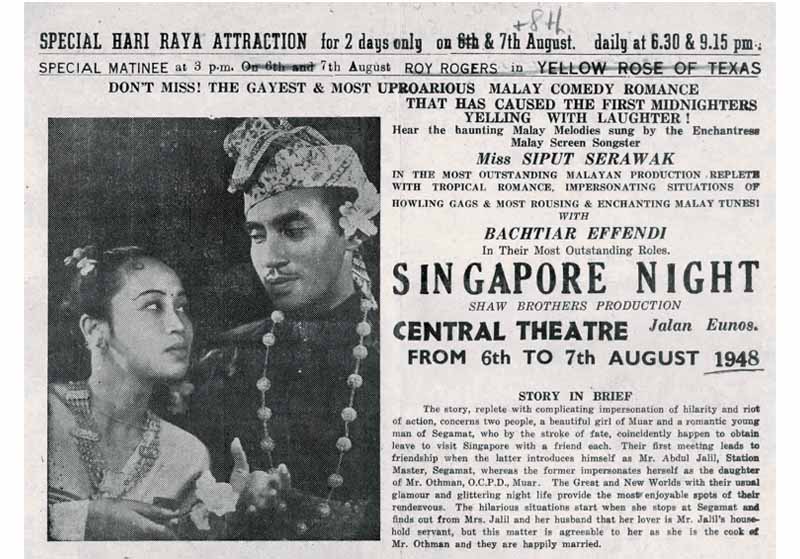

A 1948 flyer advertising Singapura Di Waktu Malam (Singapore Night), one of MFP’s earliest Malay films and starring Siput Sarawak and Bachtiar Effendi. © Singapura Di Waktu Malam. Directed by B.S. Rajhans, produced by Malay Film Productions, 1947. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

A 1948 flyer advertising Singapura Di Waktu Malam (Singapore Night), one of MFP’s earliest Malay films and starring Siput Sarawak and Bachtiar Effendi. © Singapura Di Waktu Malam. Directed by B.S. Rajhans, produced by Malay Film Productions, 1947. Courtesy of Wong Han Min.

Not to be eclipsed was rival Cathay Organisation’s Cathay-Keris Films with its studios at Jalan Keris in the East Coast area. In 1953, Cathay’s chairman Loke Wan Tho teamed up with Keris Film Productions’ managing director Ho Ah Loke to form the Cathay-Keris Studio. Cathay-Keris was to pose a serious challenge to Shaw Brothers MFP’s dominance in the Malay film industry.14

Ho was a maverick producer who cut his teeth in the industry in 1925; not only did he buy a cinema in Ipoh at the age of 25, he also rode his bicycle to small neighbouring towns to screen his reels of films.15 After a former partnership with Rimau Film Productions had run its course, Ho formed his own company, Keris Film, in 1952. Not long after, Cathay’s Loke collaborated with Ho in the production of Buloh Perindu (Magic Flute), believed to be the first Malay-language film shot in colour and released in 1953 under the Cathay-Keris Films banner.16 Due to the paucity of expertise and limited supply of filmmaking talent, Ho was said to have recruited directors of Indian origin from MFP as these auteurs had the requisite years of experience from working with the Shaw Brothers. Among the talented directors were Dato L. Krishnan, B.N. Rao and K.M. Basker.17

A turning point in the Malay film industry occurred in 1957 when a dispute broke out between the film workers union, PERSAMA (Malayan Artists Union) and executives at Shaw Brothers following the dismissal of five Malay film actors and actresses employed by MFP and agitations for wage increases and better employee prospects.18 A strike soon followed. When negotiations remained at an impasse, Cathay-Keris’ Ho allegedly muscled in on the situation by sending rice supplies and encouraging notes to the strikers in order to lure actors, directors and technicians to his studios where better remuneration and equipment beckoned.19

Following the strikes, Cathay-Keris released one of the most notable cult films in the Malay movie industry, Pontianak (1957), starring the radiant kebaya-queen from Indonesia, Maria Menado. The ghoulish tale of a beauty-turned-vampire who could only be killed by a nail driven into her skull was directed by B.N. Rao. The phenomenal success of Pontianak – which spawned the sequel Dendam Pontianak (Pontianak’s Revenge) in the same year and consequently the horror film genre – heralded the arrival of Cathay-Keris as a formidable opponent in the industry.20 Menado, too, rode the crest of her success in the Pontianak films to become Malaya’s first film-star producer with her own company, Maria Menado Productions, rivalling P. Ramlee’s status in the filmmaking sphere.21

Actress-producer Maria Menado (of Pontianak movie fame) in 1960. K.F. Wong collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

Actress-producer Maria Menado (of Pontianak movie fame) in 1960. K.F. Wong collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

A Steady Decline

Following the 1957 strike at Shaw Brothers, tensions among the Malay staff and resentment over labour disputes lingered at MFP. In a few years, most of Shaw Brothers’ Malay-language film production had moved to Kuala Lumpur.22 Its one profitable star, P. Ramlee was given the opportunity to make a film, Seniwati (Female Artiste), in Hong Kong but this deal fell through amid fears that such a venture would lack cultural resonance among the Malays and deal a blow to the local film industry.23 With diminished prospects, Ramlee moved to Kuala Lumpur in 1964, which coincided with a series of events leading to the decrease in Shaw Brothers’ Malay film production efforts in Singapore. By 1967, MFP had closed.24

Meanwhile, Cathay-Keris faced stiff competition from television and the loss of the Indonesian cinema-goers’ market due to the Konfrontasi (Confrontation) crisis between 1963 and 1966 that saw armed incursions and bomb attacks by Indonesian forces in Singapore. Cathay-Keris responded by retrenching 45 studio staff in 1965, and a further 17 staff in 1966.25 By 1972, Cathay-Keris had produced its last film, Satu Titik Di-Garisan (A Drop at the Line), marking the end of Malay film production in Singapore.

After Shaw and Cathay shut down their studios in Singapore and moved their operations to Kuala Lumpur, Singapore lost its status as the hub of the Malay film industry. The emergence of television as an alternative medium was one of the key factors that led to the demise of the homegrown tinsel towns along Jalan Ampas and Tampines.26 While marquee names like P. Ramlee tried to gain a foothold in the Malaysian film industry, film talent in Singapore decided to focus their efforts on the small screen. New made-for-TV Malay movies started trickling into the vacuum as demand for entertainment was picked up by Radio and Television Singapore (RTS), which released popular series such as Awang Temberang27 and Sandiwara.28 The void left by the end of the golden age of Malay cinema was also filled by Indonesian Malay-language films with stars such as Brorey Marantika and Dicky Zulkarnain. 29

Meanwhile, in a quirky departure from the past, independent producers made a string of English-language martial-arts-themed films: Ring of Fury (1973), Bionic Boy (1977), They…Call Her Cleopatra Wong (1978) and Dynamite Johnson (1978).30 The latter trilogy, directed by Filipino auteur, Bobby A. Suarez31 drew inspiration from the kungfu mania following Bruce Lee’s phenomenal success and the blaxploitation genre that had become hugely popular in the US.32 In particular, Cleopatra Wong, starring the 19-year-old Singaporean actress Doris Young (a.k.a Marrie Lee) quickly reached cult status and eventually inspired a young Quentin Tarantino, who later referenced the spirited, fly-kicking Interpol agent heroine who could hold her own amongst the most violent thugs and villains in his Kill Bill movies.33

In all, more than 250 Malay-language films were produced in Singapore over the 25-year reign of the golden age of local film, spawning a line-up of celebrity Malay stars in the process. These films have remained in the hearts of fervent fans who occasionally get to watch re-runs on television specials and during film festival screenings. The golden age of Malay cinema was symbolic for a generation of film audiences who had witnessed the transition from an oral storytelling tradition to a dynamic art form on the silver screen. While the study of Malay-language films remains somewhat overshadowed by other Asian cinematic arts, it is heartening to see the revived interest in these films, which are celebrated regularly at film festivals, tribute exhibitions to film-making talent of that era and, more recently, a permanent gallery at the Malay Heritage Centre in Kampong Glam.34

The authors have jointly curated a book display “ The Golden Age of Malay Cinema”, at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, Level 8, National Library Building. The display ends on 30 May 2015.

AKAN DATANG: THE ART OF THE FILEM POSTER

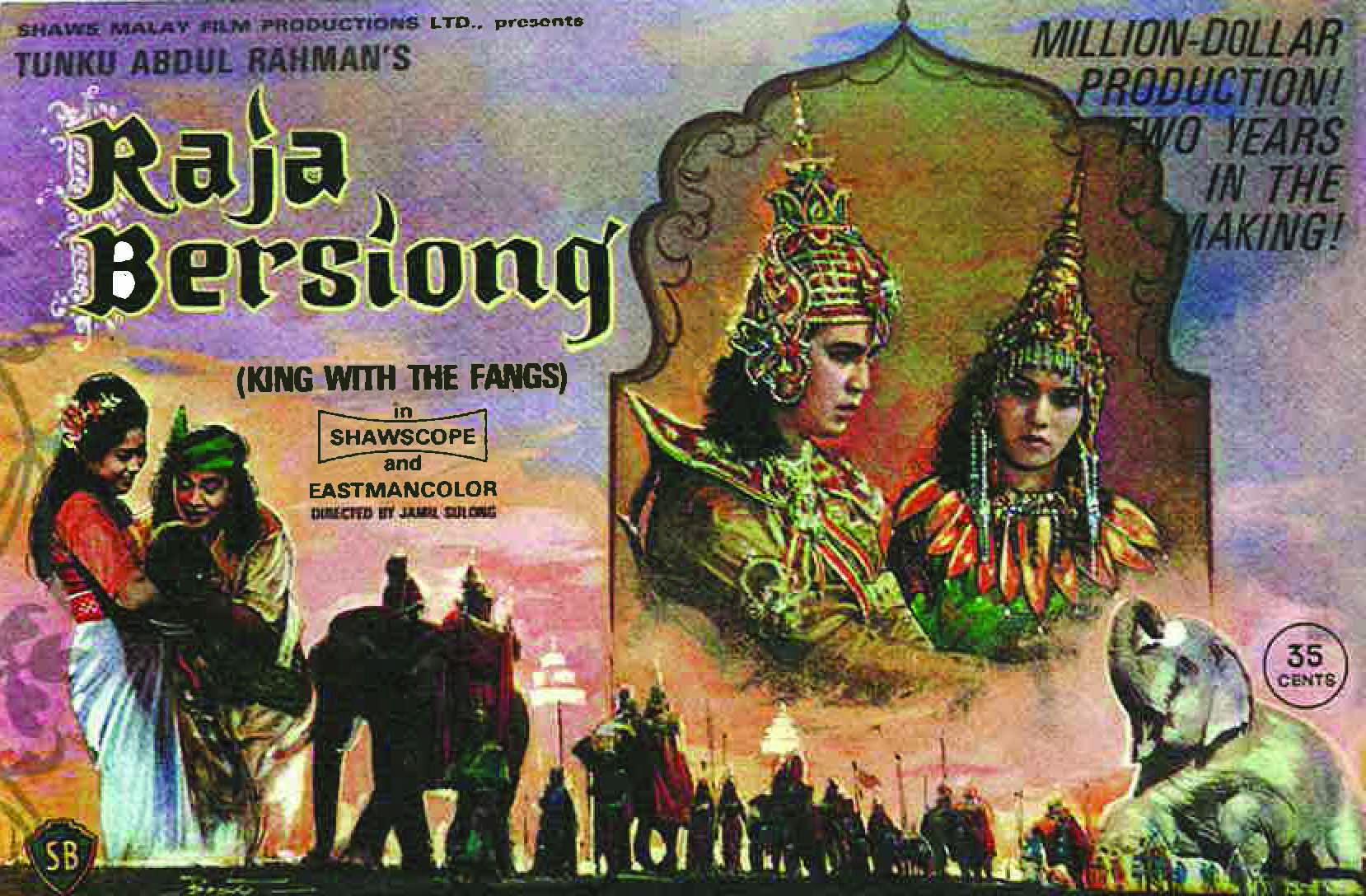

“It’s been decades but I do remember some of the people my father [director Jamil Sulong] used to work with in Jalan Ampas. The one person I remember clearly was A. V. Bapat the art director for most of MFP’s movie[s]. If you manage to get a glimpse of the old Malay film posters – more than likely that it was his handiwork (like the Raja Bersiong poster…) I like the way he painted his posters…Uncle Bapat has long since passed on, … sad that sometimes his contributions to the Malay film industry is overlooked. As far as I know, he did sets, costumes and all art direction when he was at Jalan Ampas.”35

Shaw’s Malay Film Production (MFP) Ltd and Cathay-Keris Films sustained movie-goers’ interest in new releases through film tabloids and movie billboard posters. Movie posters used to be the only way people knew about what was playing at the cinemas36 if they did not buy magazines and newspapers. In the absence of digital technology, poster painters had to draw and colour movie posters from scratch.

The late director Jamil Sulong, who joined the Shaw family in November 1951,37 recalled that Shaw added new studios to accommodate the increasing workload with the success of MFP. One of the rooms of Studio No 9 at Jalan Ampas (in the Balestier area) was where the poster artists worked.38

Shaw’s first art director was bangsawan (Malay opera) backdrop painter, Mohamamad Haniff (Pak Haniff).39 When Pak Haniff died, other local painters replaced him, such as Mustafa Yassin who remained as art director until Shaw’s last days in Singapore in 1967.40 China-born Lim Ying Chang was employed as an artist apprentice by Shaw after the Japanese Occupation. He stayed with Shaw for 10 years and eventually became chief artist.41 Eventually, Shaw brought in Indian expertise, with names such J. S. Anthony and A. V. Bapat appearing as art director in the credit roll at the start of the MFP films.42 Bapat was MFP’s art director from 1957 until the Shaw Studio closed in 1967 and is remembered for his close collaboration with director P. Ramlee. One of Bapat’s last artworks was for Raja Bersiong, a film written by the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman.43

The poster painters normally copied from pictures they were given. Although the work did not stretch their imaginations it was more important that they drew the faces of the stars as accurately as possible. More challenging was enduring the long hours of squatting over the canvasses as they painted. A team of two or three painters would work on a single billboard poster, while a huge one would take four to five days to complete.44

According to Chew Poi Yong, Cathay’s painter in the early 1950s, two key ingredients for a good poster were proportion and colour: “…the first (was) to get the exaggerated dimensions right and the second to produce work that can be seen from afar”. To get the right proportion, painters would first mark out squares on the canvas with white chalk. Once the sketch was made, they would go over the outline with a blue marker. White paint was then painted all over as background and through it the blue outline would appear as smudges. The “fun” would then begin as the painters added the other colours.45

Hand-painted film posters went through a boom from the 1950s until the 1970s with as many as 100 posters commissioned per film. In the past, as many as 10 painters would be mobilised to complete a big billboard requiring 100 pieces of plywood for mounting. As experienced painters retired and new blood could not be attracted to join the profession, dwindling manpower meant that only one painter was assigned to a poster.46 By 1980, Shaw had closed down its art studio that produced its posters47 and by the end of the 1980s, hand-painted posters had given way to their digital rivals.

Hand-painted film posters were the rage from the 1950s to 70s but slowed down by the 80s. Here, Neo Choon Teck, one of Singapore’s last surviving billboard artists, reprises his work for the Singapore Short Film Awards in 2011. Courtesy of SINdie (www.sindie.sg).

Hand-painted film posters were the rage from the 1950s to 70s but slowed down by the 80s. Here, Neo Choon Teck, one of Singapore’s last surviving billboard artists, reprises his work for the Singapore Short Film Awards in 2011. Courtesy of SINdie (www.sindie.sg).

TAYANGAN AKAN DATANG: POSTER LUKISAN TANGAN

“Beberapa dekad telah berlalu tapi saya masih ingat dengan sekumpulan teman ayah yang dahulu bekerja di Jalan Ampas. Seorang yang masih segar di ingatan saya ialah A V Bapat, Pengarah Seni untuk kebanyakkan filem MFP (Malay Film Productions). Kalau anda dapat melihat poster filem Melayu lama (seperti poster Raja Bersiong…),kemungkinan besar ia adalah hasil karya beliau. Saya minat dengan cara beliau melukis poster… Pakcik Bapat telah lama pergi dan ia menyedihkan kadang kala sumbangan beliau kepada industri filem Melayu dilupakan. Setahu saya, beliau bertugas sebagai pereka set, pakaian dan semua kerja artistik semasa di Jalan Ampas.”

Shaw dan Cathay cuba memenuhi citarasa peminat filem Melayu terhadap perkembangan filem dengan mengeluarkan tabloid dan poster filem. Bagi yang tidak melanggan sebarang makalah, poster-poster filem yang dipamerkan di pawagam setempat adalah cara terunggul untuk mengetahui tayangan terkini dan yang dapat ditonton dalam jangkamasa terdekat. Di sebalik poster gah yang terpampang, mungkin ramai tidak dapat meneka yang banyak poster filem dihasilkan oleh pelukis-pelukis yang hanya bersinglet dan seluar pendek, dengan tangan comot berlumuran cat.

“Waktu saya masih kecil, saya sering bermain di studio-studio [Jalan Ampas] ketika ibu-bapa saya sedang sibuk berkerja… Ada tiga buah studio di Jalan Ampas…Studio yang ketiga, di mana ayah saya bertugas (dan juga artis-artis yang melukis canvas untuk billboard filem) telah dirobohkan dan diganti dengan bangunan pejabat…”

Studio No 9 Jalan Ampas adalah bangunan yang banyak melahirkan poster lukisan tangan Malay Film Production (MFP). Sambutan hangat terhadap filem MFP dan kegiatan perfileman yang meningkat mendorong, Shaw untuk menaikkan bangunan-bangunan studio yang baru. Di sebuah bilik di Studio No 9 yang baru inilah tempat pelukis-pelukis poster berkarya. Mereka bekerja di bawah arahan seorang Pengarah Seni (nama glamour untuk pelukis set). Awalnya di Shaw, jawatan ini disandang oleh Mohamamad Haniff (Pak Haniff), seorang pelukis pentas bangsawan. Ia merupakan pencapaian yang membanggakan kerana Shaw pada era ini lebih banyak mengutamakan karyawan-karyawan import dari India, China dan Hong Kong untuk memenuhi jawatan pengarah dan juruteknik filem. Setelah pemergian Pak Haniff, jawatannya di ambil-alih oleh pelukis tempatan Mustafa Yassin yang terus berperan sebagai Art Director sehingga hari-hari akhir Shaw di Singapura. Pelukis kelahiran China, Lim Yin Chang, juga diambil oleh Shaw untuk berkhidmat sebagai pelukis perantis selepas perang Jepun. Beliau menimba pengelaman selama sepuluh tahun dan berjaya menjadi Chief Artist (Ketua Seni) sebelum meninggalkan studio Shaw. Namun Shaw turut menggajikan pelukis dari India untuk pimpinan artistiknya dan nama-nama seperti J S Anthony dan A V Bapat dapat terlihat sebagai Pengarah Seni di dalam credit roll bagi filem-filem MFP. Bapat menjadi sebagai Pengarah Seni MFP dari 1957 sehingga studio itu tutup pada 1967 dan banyak menyimpan kenangan manis ketika dia bergabung dengan pengarah legenda P Ramlee. Salah satu hasil terakhirnya adalah untuk filem Raja Bersiong, karangan mantan Perdana Menteri pertama Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Sebagai pelukis poster, mereka banyak meniru gambar yang tersedia ada. Hal ini tidak memeras kreativiti pelukis, namun melukis wajah-wajah pelakon dengan tepat tetap diutamakan. Yang lebih mencabar ialah mereka terpaksa menahan lenguh dan letih akibat bercangkung berjam-jam untuk menyiapkan poster, sehingga mencetuskan gurauan yang pelukis berperut gendut tidak akan sanggup melakukan perkerjaaan ini. Lazimya dua atau tiga orang diberi sebuah poster untuk disiapkan dan poster ukuran besar memakan masa empat atau lima hari untuk siap.

Dua ciri utama untuk menjayakan poster ialah keseimbangan dan warna. Menurut Chew Poi Yong, seorang pelukis Cathay sejak tahun 50an, ciri pertama penting untuk mencapai penglebaran ukuran yang baik dan ciri kedua penting untuk membolehkan poster dilihat dari jauh. Untuk memudahkan pelukis dalam penglebaran yang seimbang, mereka akan membuat tanda empat persegi dengan kapur putih. Selepas melakar gambar dengan marker biru, mereka mencurahkan cat putih ke atasnya untuk warna latar dan corengan dari lakaran gamabr tadi akan timbul. Maka bermulalah kegiatan mencorak gambar itu dengan warna-warna yang lain.

Permintaan untuk poster begitu rancak dari 50an ke 70an, hingga 100 keping boleh ditempah untuk setiap filem. Namun, pelukis-pelukis yang telah lama berkecimpung mula bersara sementara anak-muda tidak berminat untuk menceburi kraf ini. Kalau dahulu, seramai 10 pelukis dapat digembeling untuk menyiapkan sebuah billboard gah yang memerlukan 100 keping plywood sebagai backing. Dengan masa, tenaga yang sudah berkurangan menjadikan sebuah poster itu terpaksa disiapkan oleh seorang pelukis sahaja. Setelah berakhirnya tahun ‘80an, poster lukisan tangan mula akur dengan kehebatan poster digital. Bermula 1980, Shaw telah menutup studio yang membuat poster filemnya. Pada 2005, hanya seorang pelukis poster, Neo Choon Teck, yang tinggal.

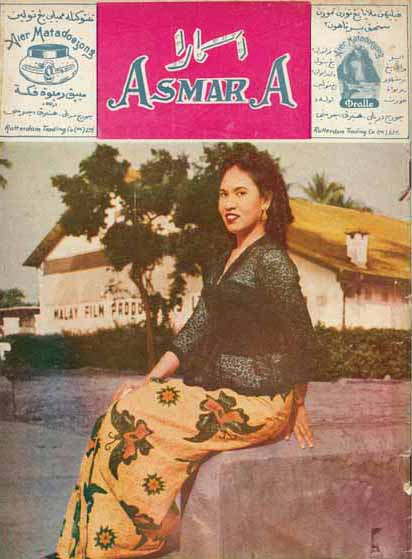

Actress Normadiah on the cover of the now defunct Malay-language entertainment monthly magazine, Asmara. MFP studio at Jalan Ampas stands in the background. © Asmara, Issue 23. Published by S.O.A. Alsagoff for Geliga Publication Bureau (Singapore), 1956.

Actress Normadiah on the cover of the now defunct Malay-language entertainment monthly magazine, Asmara. MFP studio at Jalan Ampas stands in the background. © Asmara, Issue 23. Published by S.O.A. Alsagoff for Geliga Publication Bureau (Singapore), 1956.

Raja Bersiong is a 1968 historical film written by former Malaysian prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman. © Raja Bersiong. Directed by Jamil Sulong, produced by Malay Film Productions, 1968.

Raja Bersiong is a 1968 historical film written by former Malaysian prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman. © Raja Bersiong. Directed by Jamil Sulong, produced by Malay Film Productions, 1968.

NOT LOST IN TRANSLATION

Now, to increase my income, a friend of mine told me that, “Now, you can do some part-time work or subtitling for the film… In the pictures, we had to subtitle in English. He said, “You go to the studio, you write down the whole script yourself, then you write in English, you type it out, number it and then give it to the staff at the studio and they will do the work for you … But the amount of work was so much … after I’d finished my work in the evening at 5 o’clock, I go to the studio and work there until 12 o’clock…” (Bana Nazeem. 1981, November 22. Pioneers of Singapore (oral interview), reel 3, p. 3. Retrieved from the National Archives of Singapore).

After World War II, Shaw and Cathay realised that including subtitles in foreign-language films was a surefire way to attract local audiences to cinemas and ensure extended movie runs. Malay fans, enamoured of Bollywood films, soon formed snaking queues at Taj and Garrick cinemas in Geylang in the 1950s and 60s,48 thanks to the Malay subtitles in Hindi films.49 In fact, a decade before Hindustani megastar Dev Anand kept Malays gripped to their seats with his enigmatic fighting scenes, Chinese-educated masses in Singapore who did not understand English had already been drawn to American and British films because the screenings had included Chinese subtitles.50

Due to increasing demand, a pool of specialists and operators was employed to translate the foreign plots and lines.51 In 1948, it was reported that there was only a handful of such specialists in Singapore and their job was described as “one of the hardest and most exciting tasks in the cinema business”.52 For the 1948 blockbuster Hamlet, Cathay employed a Hong Kong graduate, Lau Shing-yuen, to translate and prepare slides for its Chinese film subtitles53 that were projected onto a small screen beneath the main screen. Getting the Chinese characters printed on the glass slides was a two-step process; first, painting the Chinese words in ink over the little glass slides followed by scratching the Chinese characters onto the glass surface with a metal stylus.

In 1953, a new form of subtitling was introduced. The previous method outlining the plot was not an accurate way of capturing the dialogue of the film.54 To improve this, subtitles were superimposed onto the film itself, enabling nearly 1,000 subtitles to be dubbed for each film. The new method premiered first in Hong Kong before becoming a hit in Singapore.55

Malay films of the 1950s and 60s, particularly P. Ramlee films, appealed to Malaya’s cosmopolitan society because the universal themes they portrayed cut across language and cultural barriers. 56 In order to cater to non-Malay-speaking audiences, English subtitles were provided in Malay movies.57 The then sole translator, writer Zulkifli Haji Muhammad, joined Shaw Brothers’ Jalan Ampas studio in 1960, eventually becoming assistant director, directing Malay films for Shaw.58

A Chinese flyer promoting Anak Pontianak (1958). Directed by Roman Estella, produced by Malay Film Productions Ltd. Singapore/ Hong Kong, 1958

A Chinese flyer promoting Anak Pontianak (1958). Directed by Roman Estella, produced by Malay Film Productions Ltd. Singapore/ Hong Kong, 1958

TERJEMAHAN BERKESAN: SARIKATA DALAM FILEM MELAYU

Selepas perang, Shaw dan Cathay melihat kesan positif dari penggunaan sarikata (sub-titles) yang telah merancakkan lagi sambutan terhadap tayangan filem-filem bahasa asing mereka. Peminat filem dari masyarakat Melayu yang berduyun-duyun ke Taj dan Garrick di Geylang dalam 50an dan 60an terkena demam Bollywood kerana dapat memahami filem hindi menerusi sarikata yang disediakan dalam Bahasa Melayu. Bahkan sedekad sebelum Dev Anand memukau penonton Melayu dengan aksi pertarungannya yang hebat, penonton-penonton Cina di Singapura yang tidak fasih dalam bahasa Inggeris telahpun tertarik untuk menonton filem-filem dari Amerika dan Britain kerana tersedianya sarikata dalam bahasa Cina. Sekumpulan pakar dan operator penterjemah telah digajikan untuk menyiapkan sarikata filem. Pada 1948, dilaporkan hanya segelintir sahaja menjadi tenaga pakar ini dan mereka dikatakan memikul tugas yang paling sukar dan teruja dalam industri perfileman. Untuk filem blockbuster Hamlet yang ditayangkan dalam 1948, Cathay telah melantik seorang siswazah dari Hong Kong, Lau Shing-yuen, untuk menterjemah dan menyiapkan slides dalam bahasa Cina, yang kemudian dipancarkan ke skrin kecil di bawah tayangan gambar. Menyalin huruf Cina ke slides tersebut harus melalui dua tahap: melukis huruf degan Chinese ink dan memahat huruf Cina itu di atas slide kaca dengan stylus logam. Dalam 1953, cara ini telah diperbaharui kerana ianya hanya memuatkan plot filem secara ringkas dan kurang memaparkan jalan cerita dan dialog filem dengan sempurna. Untuk meningkatkan mutu terjemahan, sarikata sekarang dicetak langsung ke dalam filem dan ia dapat menghasilkan hampir 1000 sarikata bagi setiap filem. Cara baru ini dilancarkan di Hong Kong sebelum diperkenalkan di Singapura.

Filem-filem Melayu Shaw dan Cathay terutama karya P Ramlee disambut baik oleh masyarakat majmuk di Malaya kerana tema universalnya yang tidak kenal bahasa atau budaya. Filem klasik Melayu dapat dinikmati oleh peminat filem dari bangsa lain kerana disediakan sarikata dalam Bahasa Inggeris. Salah satu penterjemahnya ialah penulis Zulkifli Haji Muhammad yang mula menjalankan kerja-kerja sarikata di studio Jalan Ampas pada 1960 sebelum dilantik sebagai Penolong Pengarah. Mrs Wee, seorang lagi mantan pekerja Jalan Ampas dan teman kepada bintang legenda P Ramlee, banyak memeras tenaga untuk menyediakan sarikata untuk filem Melayu Shaw. Empat puluh tahun setelah studio Shaw ditutup pada 1967, beliau mengunjungi Jalan Ampas dan bangunan-bangunan renta di kawasan itu mengingatkan beliau kembali kepada hari-hari yang banyak beliau habiskan di salah satu Studio Shaw untuk menyunting dan mencetak sarikata ke dalam filem.

Nor Afidah Bte Abd Rahman is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore and a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She compiled and edited Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012), and more recently, Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2014).

REFERENCES

Amir Muhammad. (2010). 120 Malay movies. Petaling Jaya: Matahari Books. (Call no.: RSEA 791.430899923 AMI)

Fu, P. (Ed.). China forever: The shaw brothers and diasporic cinema. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43095125 CHI)

Harding, J., & Ahmad Sarji. (2002). P. Ramlee: The bright star. Selangor, Malaysia: Pelanduk Publications. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43028092 HAR)

Hassan Abd. Muthalib. (2013). Malaysian cinema in a bottle: A century (and a bit more) of wayang. Selangor, Malaysia: Merpati Jingga. (Call no.: RSEA 791.4309595 HAS)

Jamil Sulong. (1990). Kaca permata: Memoir seorang pengarah. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa and Pustaka. (Call no.: RSING 799.4309595 JAM)

Lim, K.T., & Yiu, T.C. (1991). Cathay: 55 years of cinema. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 LIM)

Millet. R. (2006). Singapore cinema. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL)

Mohd Zamberi A Malek & Aimi Jarr. (2005). Malaysian films: The beginning. Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD)

van de Heide, W. (2002). Malaysian cinema, Asian film: Border crossings and national cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43 VAN)

NOTES

-

Amir Muhammad. (2010). 120 Malay movies (pp. 120–121). Petaling Jaya: Matahari Books. (Call no.: RSEA 791.430899923 AMI) ↩

-

Amir, 2010, pp. 120–121; Harding, J., & Ahmad Sarji. (2002). P. Ramlee: The bright star (pp. 98–99). Selangor, Malaysia: Pelanduk Publications. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43028092 HAR) ↩

-

Hassan Abd. Muthalib. (2013). P. Ramlee: Birth of an enduring legend. In Malaysian cinema in a bottle: A century (and a bit more) of wayang (p. 55). Selangor, Malaysia: Merpati Jingga. (Call no.: RSEA 791.4309595 HAS); Mafoot Simon. (1983, May 31). Tribute to an artiste of varied talents. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hassan, 2013, p. 55; Mafoot Simon. (1997, May 29). No one has come close to him. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Millet. R. (2006). Singapore cinema (p. 28). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL); Malay film of the occupation. (1947, March 10). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Mohd. Zamberi A Malek & Aimi Jarr. (2005). Post-war malay films (pp. 115–120). In Malaysian films: The beginning. Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD) ↩

-

Barnard, T.P. (2008). The shaw brothers’ malay films (p. 156). In P. Fu (Ed.). China forever: The shaw brothers and diasporic cinema. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43095125 CHI); Mohd Zamberi A. Malek & Amir Jarr. (2005). The development of malay films (pp. 74–77). In Malaysian films: The beginning. Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD); Page 7 Advertisements Column 2: Malborough Theatre. (1934, March 24). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zamberi & Amri, 2005, pp. 115–120. ↩

-

Millet, 2006, p. 29; Hassan Abd. Muthalib. (2013). Film arrives in the Nusantara (p. 39). In Malaysian cinema in a bottle: A century (and a bit more) of wayang. Selangor, Malaysia: Merpati Jingga. (Call no.: RSEA 791.4309595 HAS). Directed by B.S. Rajhans, Singapua Di-Waktu Malam’s plot focused on the plight of prostitutes in Singapore and starred as Chempaka (Magnolia, 1947); Pisau Beracun (The poisoned knife, 1948); Chinta (Love, 1948); First post-war malay film shown. (1947, November 16). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Muthalib, 2013, p. 35; Mohd. Zamberi A Malek & Aimi Jarr. (2005). Pre-war malay films (p. 97). In Malaysian films: The beginning. Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD); Millet, 2006, pp. 39–45. ↩

-

Mohd Zamberi A Malek & Aimi Jarr. (2005). Malaysian films: The beginning (pp. 166–170). Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan: National Film Development Corporation Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 MOD) ↩

-

Barnard, 2008, p. 158; Harding & Sarji, 2002, pp. 14–15; Tan, K.H. (1988, December 9). Screen legend lives on. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, K.T., & Yiu, T.C. (1991). Cathay: 55 years of cinema (p. 119). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 LIM); Take one…reference book on Malay movie history. (1997, August 14). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zamberi & Aimi, 2005, p. 154. Directed by B.S. Rajhans, Buloh Perindu gave Shaw Brothers their first taste of real competition. The big budget film was produced in Geva Colour and shot on location in Chuping, Perlis and showcased a line-up of film-stars such as Salleh Ghani, Shariff Medan, M. Amin, Raden Sudior, Bakarudin, Yusof Kelana, Raden Rafeah, Raden Sumiani, Rosni and Norsiah Yem. ↩

-

Barnard, 2008, p. 163; Actors on strike today. (1957, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hassan Abd. Muthalib. (2013). Cathay-Keris – A different kind of Malay films (pp. 72–73). In Malaysian cinema in a bottle: A century (and a bit more) of wayang. Petaling Jaya: Merpati Jingga. (Call no.: RSEA 791.4309595 HAS) ↩

-

Lim & Yiu, 1991, p. 120; Ramani, V. (2005, August 24). Scream queen. Today, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim & Yiu, 1991, p. 139; Film company goes into liquidation. (1967, October 28). The Straits Times, p. 6; Studio jalan ampas di-katakan hendak di-tutup. (1965, May 8). Berita Harian, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim & Yiu, 1991, p. 139; Film studio cutting down staff. (1965, March 30). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Amir Hamzah Shamsuddin. (1977, December 4). Dapatkan filem 2 Melayu rebut kembali zaman gemilangya? Berita Harian, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Anuar Othman. (1987, July 31). Salim Bachik dramatis belum ada gantiny. Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chapter 8: Channel surfing. (2013, December 3). Today, p. 58. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Coltoras. (2012, March 15). Nostalgia tahun 70an: Brorey Marantika. Retrieved from Coltoras website. ↩

-

Cheah, P. (2011). Beginning and starting over – Singapore film until 2002 (p. 13). In Y. Michalik (Ed.), Singapore independent film. Marburg (Germany): Shuren. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 SIN) ↩

-

Travelfish. (n.d.). Malay Heritage Centre: A crash course in all things malay. Retrieved from Travelfish website. ↩

-

Anwardi Jamil. (2007, November 9). Anak wayang. People I remember in MFP. Retrieved from sayaanakwayang.blogspot.com website. ↩

-

The odd job. (2005, August 9). The Straits Times, p. 94. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Jamil Sulong. (1990). Kaca permata: Memoir seorang pengarah (pp. 24–25, 54). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa and Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay RSING 799.4309595 JAM) ↩

-

Van de Heide, W. (2002). Malaysian cinema, Asian film: Border crossings and national cultures (p. 259). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43 VAN) ↩

-

Jamil, 1990, p. 35; Salma Semono. (2003, March 6). Pahit manis pengelola majalah hiburan zaman 60-sanh. Berita Harian, p. 11; Bintang2 filem mangsa2 banjir. (1967, January 20). Berita Harian, p. 2; Lukisan dalam pameran: Bantas keras. (1962, September 29). Berita Harian, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, M.S. (1982, April 14). Those huge cinema posters. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Jamil, 1990, p. 35; Farith Faruqi Sidek. (2013, June 21). Kitab tawarikh. A.V. bapat: Dari Bombay ke Kuala Lumpur, sentuhan sninya merentasi zaman. Retrieved from harithsidek blogspot ↩

-

Magiar Simen. (1967, October 27). Jins tidak terlibat dalam tindakan majikan. Berita Harian, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tang, G. (1980, July 11). Keeping you posted on the latest movie. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 11 Jul 1980, p. 3; Billboard beem ended in 80s. (1993, February 5). The New Paper, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The New Paper, 5 Feb 1993, p. 22. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 11 Jul 1980, p. 3; The Straits Times, 9 Aug 2005, p. 94. ↩

-

Kurang-nya filem2 Hindustan, filem China jadi ganti. (1969, September 5). Berita Harian, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tiga kesah dlm satu gambar. (1959, January 30). Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ferroa, R. (1948, June 1). Putting them wise. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 1 Jun 1948, p. 2; 1,000 workers benefitted. (1962, May 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 1 Jun 1948, p. 2. ↩

-

Hamlet in 3,070 characters. (1948, August 25). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New sub-titling to help Chinese film fans. (1953, April 19). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Apr 1953, p. 3; Filem mini penoh dengan lagu2 yang tetap menghibor. (1961, March 11). Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, K.C. (1989, January 14). Golden movies of P Ramlee. The New Paper, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Halaman 8 iklan ruangan 1. (1964, May 5). Berita Harian, p. 8; Halaman 10 iklan ruangan 1. (1964, April 22). Berita Harian, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bahyah Mahmud. (1965, October 16). Suami Sarimah akan menarek diri dari dunia perfileman. Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩