A Moving Journey: Film, Archiving and Curatorship

As the Asian Film Archive celebrates its 10th anniversary, Karen Chan takes a look back at the genesis of the organisation, the work it does and its plans for the future.

In 2005, I was introduced to a soft-spoken but tenacious young man who had singlehandedly established the Asian Film Archive (AFA) in Singapore. What drew me to Tan Bee Thiam’s project was his vision: to set up a Pan-Asian institution that aspired to provide a repository for all Asian films – many of which had yet to be archived in their own countries. Partly curious as to how this not-for-profit, independent organisation would survive, and partly enthused by the prospect of contributing towards the maintenance, preservation, restoration and curation of archival films, I set aside my practical and less than adventurous nature and took the plunge – joining the AFA as an archivist in 2006, assuming the role of acting director in 2010 and subsequently taking over the reins as executive director in 2014. As the AFA celebrates its 10th anniversary this year, I take a look back on a journey that has been both challenging and exhilarating by turns.

From a professional viewpoint, getting the fledgling AFA organised and functioning took a staggering amount of work. Today, Southeast Asian countries have their own national archives while a few host an audiovisual archive department as a unit within the larger entity, such as in the case of the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) and Arkib Negara Malaysia (National Archives of Malaysia). However, organisational film archiving in Southeast Asia was in its infancy as recently as 10 years ago when only Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam and Thailand had their own dedicated film archives. This was the state of the film archiving landscape in the region when the AFA first began. Over the years, Cambodia and the Philippines have established their own film archives.

Film Archives in Southeast Asia

The first film archive to be set up in Southeast Asia was the Sinematek Indonesia (Indonesian Cinematheque), established in 1975 under the late Misbach Yusa Biran (a 1997 South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archive Association Lifetime Achievement Awardee and 2010 Fellow recipient). But in spite of his pioneering archiving work, by 2010, the Sinematek was, in Misbach’s words, “at its sunset”.1

On the other side of the Southeast Asian divide, the Vietnam Film Institute (VFI), one of the region’s older film archives formed in 1979, was tasked to archive Vietnam’s cinematic and audiovisual heritage as well as function as its distribution and research arm. The VFI has been much more successful in its endeavours and through its links with INA (Institut National de L’audiovisuel, France), is planning to start a digitised library in Hanoi.2

The Film Archive (Public Organisation) Thailand began as the Thai Film Archives in 1984 under Dome Sukavong. For years it remained a neglected unit within the Department of Fine Arts before becoming a public organisation in 2009. The archive has survived to celebrate its 30th anniversary in a new building with better facilities. 3

Laos’ film industry was sidelined by its long period of civil war. The National Film Archive and Video Center (Lao Cinema Department), established in 1991, was charged with preserving the country’s audiovisual heritage. With UNESCO’s assistance, the department has successfully developed a database of the country’s film archives. 4

Cambodia came into the archiving scene in 2006 with the opening of the Bophana Center, founded by the acclaimed Cambodian film director, Rithy Panh. Offering free access to its collection of film, television, photography and sound archives, researchers and local film enthusiasts finally had access to a resource for Cambodian audiovisual materials.5 Unfortunately, the archive’s limited annual budget makes it a constant challenge for the staff to expand its services.

The archiving situation in the Philippines is a complex one given that the film preservation function is encapsulated within the archiving of audiovisual materials. Instead of a centralised body overseeing the archival of films, the work was split between three government institutions – the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP), the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the University of the Philippines Film Institute. It was only in 2011 that the FDCP formed a National Film Archive of the Philippines.6 Critics have long disparaged the government’s inaction in the area of film archiving, likening it to “a blind man in the creative industry”.7 Digna H. Santiago, a film marketing professor from the De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde in Manila noted that the government “does not have the foresight of preserving films because they view the industry as one that only provides temporary entertainment.”8

Given the challenging film archiving scenarios in these various countries, it was clear that an Asia-wide organisation such as the AFA would be relevant and necessary. Within the first year of the AFA’s Reel Emergency Project’s open call for the deposit of films for preservation, hundreds of films and related materials such as photographs and publicity kits from Singapore and countries from all over Asia were submitted.

AFA’s Ethos and Practices

When the AFA first started, its two-man team grappled with the ethos and practices that would drive the archive, besides spending countless hours building up the collection. Janna Jones’ observations about a moving image archive succinctly captures the complexity of the organisational practices involved in film archiving: there is a certain “dialectic of creation and destruction, control and chaos… logic and ingenuity, order and disruption” that define the “discovery, interpretation, re-presentation, and accessing”9 of the visual experience of cinema, she says.

An archive is a space managed by rational and disciplined logic but yet decisions made in those early years were based on both intuition and logic, by marrying the personal with the professional. The AFA’s survival depended on how it would manage the balancing act of creating a sustainable archive that could serve its stakeholders effectively while at the same time bringing together accessible and meaningful programmes for its users.

Developing a set of acquisition, selection and preservation policies was imperative. These policies were drafted using reference points from the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) Code of Ethics; Ray Edmondson’s Audiovisual Archiving: Philosophy and Principles (Paris, UNESCO, 2004); and The UNESCO Recommendation on the Preservation of Moving Images (1985). It would be beyond the scope of this article to delve into a discussion on the principles and philosophies of film archiving. However, I will articulate some of the main points underlying the AFA’s preservation policies.

While its name dictates Asia as its collection ambit, the AFA has focused its preservation efforts in the last nine years on the geographical region of Southeast Asia. As mentioned earlier, until recently, Southeast Asia had very few dedicated film archives with the means and budgets to archive the numerous films produced in the region. Nevertheless, concentrating on Southeast Asia did not limit the films that the AFA acquired for its collection – it currently archives titles from wider Asia, such as China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India and Iran.

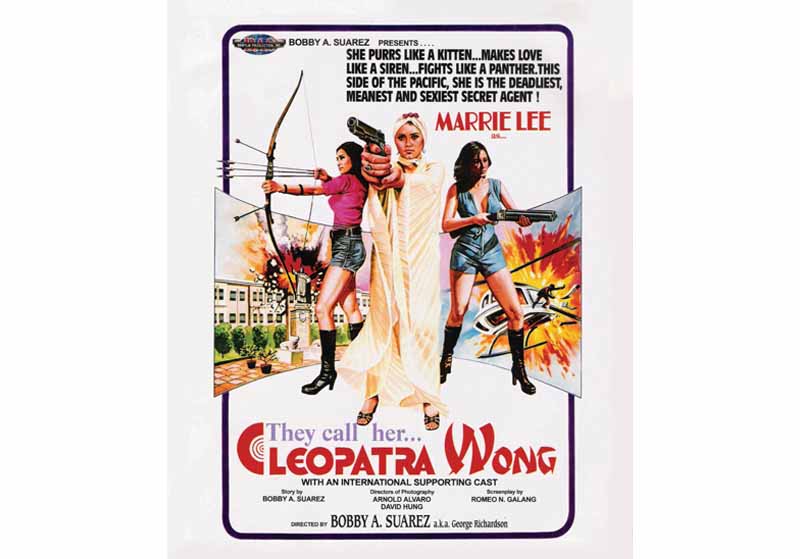

They Call Her... Cleopatra Wong was released in 1978, and starred Marrie Lee as an Interpol agent. This poster is part of the AFA's holdings. © Cleopatra Wong International Pte Ltd.

They Call Her... Cleopatra Wong was released in 1978, and starred Marrie Lee as an Interpol agent. This poster is part of the AFA's holdings. © Cleopatra Wong International Pte Ltd.

Although archives are generally associated with the antiquated, the AFA’s collection is relatively young by archival standards, with 70 percent of its films dating back to an average of 25 years. The main reason is because the AFA makes a conscious effort to acquire the works of living filmmakers. The selection criteria are determined by a list of priorities, taking into account the condition of the films’ formats and the “Asian-ness” and significance of the films on the cultural landscapes of both its country of origin and internationally. In addition, films that are independently produced and are not preserved in the home country of the filmmaker or by any other archive, receive particular attention. These guidelines are detailed on the AFA’s website and the mechanics of how films can be submitted for assessment and preservation are elaborated in the website’s Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) section.10

With the advent of the digital age, archivists are scrambling to care for their analogue systems, digitising and migrating analogue materials while keeping up with technological advances in order to preserve new digital material. Apart from the practical concerns of know-how and time, there is the very real issue of funding to support on-going digital preservation. The estimated cost (in 2007) of preserving film archival master material per title annually was US$1,059 while the digital preservation of the same material was estimated at US$12,514.11 Factor in inflation and the growing numbers of digital films produced every year, and the figure becomes mind-boggling.

The exponentially burgeoning budgets required for digital preservation bring to fore several important issues – acquisition, access and advocacy. Archives can no longer make do with an ad hoc policy to “acquire everything, just in case”. The AFA has in place a carefully articulated selection policy that is tied to access issues. An archivist has to look backwards and forwards in time, acquiring filmic material and assessing if someone in the future may find the material significant and useful.12 The AFA will likely not acquire a film if the filmmaker stipulates that it is not meant for public access, unless the reasons for the restricted access are acceptable – for example, a film cannot be released until after its film festival premiere or a film cannot be viewed due to the deteriorating condition of the sole surviving film copy until an access copy has been made.

As Sam Kula, former director of the National Film, Television and Sound division of the National Archives of Canada, has stated so articulately, “In archives, the only thing that really matters is the quality of the collections; all the rest is housekeeping.”13

The Importance of Archiving

To raise the funds needed to run a film archive, modern archivists must advocate for their cause while ensuring that potential donors understand why the archive’s work is important, and its impact on heritage and artistic preservation. Regardless of the worthiness of the film archive’s intentions, the public will not support preservation without seeing its results. Archivists need to make their work visible in order to raise the public’s awareness of what exactly archives do. Only then can archives elicit continued support and generate new revenues.14 Over the years, the AFA has done its best to connect with the public and its stakeholders by promoting and showcasing its programmes in order to garner support and goodwill. This was particularly important during those early years when the AFA was an independent not-for-profit organisation and depended solely on public funding.

Aside from the variety of talks, workshops and film screenings for educators, students, the film community and the general public, the AFA has organised different events to create awareness on film preservation. The Save Our Film campaign in 2010 was a collaboration with final-year students from Nanyang Technological University’s Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information. It was aimed at raising awareness among youths aged 15 to 35 on Singapore’s rich local film heritage and the importance of keeping it alive for future generations. The campaign featured a series of nationwide guerrilla-style publicity efforts such as mock DVDs and posters at supporting stores and cinemas that promoted early Singapore titles with a twist; video projections on walls and ceilings at public spaces; and a roving showcase featuring recordings from local film community personalities.15 Another more recent effort in 2014 to raise the profile of AFA’s preservation efforts was its successful inscription of 91 Cathay-Keris Malay Classics into the UNESCO Memory of the World Asia-Pacific Register.16

Nonetheless, advocating film preservation is an uphill task, especially when there are so many equally worthy public causes competing for funds. In an effort to take on a more proactive curatorial role and shed the passivity that archives are usually associated with, film archives all over the world are using technology to restore older titles in their collection and make these films more accessible to the public.17 Through such restoration projects, the archive is able to more effectively advocate for its work through the films it chooses to restore and the strategic activities it can organise in connection with the restored films. However, film restoration is a highly expensive investment; the restoration of a single film could cost upwards of S$100,000, depending on its condition. Although the AFA has embarked on the restoration of a number of important films and has accompanying programmes lined up, its other functions, specifically, preservation and access, remain a priority. After all, without preservation, there would be no films to restore: the restoration process is only a means to achieve the larger and overarching goal of film preservation.

Part of AFA’s advocacy efforts is to create greater awareness of its work in the region, and what better way to do that than by spreading the word through the regional archiving community. A year after the AFA’s formation, it applied for membership to the South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA). This is an association of organisations and individuals involved in the development of audiovisual archiving in Southeast Asia, Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), and the Pacific Islands (Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia). Currently over 38 countries are members of SEAPAVAA.

Shortly after, in 2007, the AFA became the first Singapore-based organisation to become an affiliate of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Being a member of these associations has helped AFA to develop relationships between archivists and the wider film communities, allowing for an exchange of information, experiences and networking opportunities. Annual conferences have provided further avenues for the AFA to share its work as well as learn from the many professionals who attend these conferences.

The AFA has come a long way from when it started 10 years ago by the visionary Tan Bee Thiam. Having built a reputation and gained traction with the regional film community, AFA’s mission statement – “To Save, Explore, and Share the Art of Asian Cinema” – will continue to guide its future work and direction. The editors of Film Curatorship: Archives, Museums and the Digital Marketplace succinctly define film curatorship as “the art of interpreting the aesthetics, history, and technology of cinema through the selective collection, preservation, and documentation of films and their exhibition in archival presentations.”18 On this occasion of the AFA’s 10th anniversary, this quote eloquently encapsulates what the words “Save, Explore and Share” in AFA’s mission statement hopes to achieve.

THE GENESIS OF THE ASIAN FILM ARCHIVE

The Asian Film Archive (AFA) was the brainchild of Tan Bee Thiam, its founder and former executive director. After graduating from the National University of Singapore (NUS) in 2004, Tan embarked on a two-month backpacking trip that took him to New Delhi, India. Unbeknownst to him at the time, this visit would sow the seeds for the beginnings of the first Singapore-based film archive. Tan had always been a film enthusiast; as a student he served as the president of the NUS film society, nuSTUDIOS, and was himself an emerging filmmaker. In New Delhi, Tan attended the Osian’s-Cinefan: 6th Festival of Asian Cinema, where he was exposed to key filmmakers from around Asia.

These figures, including members from NETPAC (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema), like Singapore’s Phillip Cheah and India’s Aruna Vasudev, would later inspire and influence his thoughts. NETPAC’s mission is to promote lesser known Asian films. “The organisation impressed me,” recalls Tan. “A lot of media attention is given to the glamour of the Cannes, Venice and Berlin film festivals. But there are very hardworking Asian filmmakers who create works for their own people. I felt that their work, at least those I’d seen, were important and groundbreaking.”

Tan had the good fortune of acting as translator for the post-screening Q&A sessions of the acclaimed Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming Liang. In their conversations, Tsai provoked Tan into thinking about archiving and its importance. “(Tsai) had problems with distribution, problems with keeping track of his own film prints,” recounts Tan. “Even for a very established filmmaker like Tsai Ming Liang, his works were rarely seen outside of film festivals.” This led to conversations with other Asian filmmakers such as award-winning Malaysian director U-Wei Haji Saari, who revealed that he stored the film prints of his acclaimed films himself, acknowledging that in a tropical environment, they would run the risk of being damaged.

Tan quickly recognised the challenges these Asian independent filmmakers faced. Not only did they have trouble raising money to produce their films, these works did not always receive the traction they deserved, denying audiences the opportunity to view them. Many films might not even survive the passage of time; in 2004, few Asian countries had their own national film archive, and those that existed did not function effectively. Without proper preservation facilities, it was clear to Tan that significant elements of Asian heritage and culture would be lost forever.

The Basis

In the course of his research, Tan drew inspiration from the great work of the British Film Institute (BFI), Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive and Asian film archives in Taiwan, Thailand and Hong Kong. International and regional film institutions such as the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) and the South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA) offered further insight into the different models he could pursue.

Upon his return from India, Tan was pleasantly surprised to discover that there had already been suggestions to establish a Singapore film archive. He spent the next few months networking, meeting filmmakers and heads of institutions as well as film researchers, laying the foundations and framework the archive would be built upon.

Tan envisioned that the archive would be situated in the context of a university, to be enjoyed not just for entertainment but as a form of art and for serious study, providing resources for research and academia. He also wanted to situate Singapore cinema in the wider context of Asian cinema – a film archive that would be Asian in its scope and focus.

Tan turned to his alma mater, NUS, and approached Chew Kheng Chuan, founding director of NUS’ Development Office and chairman of The Substation (Singapore), who supported Tan’s vision. He offered Tan not only his wealth of experience, but also office space within the NUS Development Office – the AFA’s first home.

The Birth

Tan approached his NUS schoolmate, filmmaker Kirsten Tan, with whom he had made films with when they were in nuSTUDIOS. Kirsten gave Tan her full support and joined him as a co-founder. He also approached Kenneth Paul Tan, an NUS political science professor at the time, and Kenneth Chan, an assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) humanities school. Jacqueline Tan, a lecturer for the Film, Sound & Video (FSV) course at Ngee Ann Polytechnic, and Straits Times journalist and film critic Ong Sor Fern rounded out the team, forming the first governing board of the AFA.

The team was met with scepticism in their search for archival space and funding. People were hesitant to collaborate with the AFA as it was unproven in an endeavour that other established institutions had attempted but failed. This changed when Tan emailed a Christmas greeting to NAS’ then director, Pitt Kuan Wah, in December 2004. This email proved to be a game changer.

Pitt and NAS’ then deputy director of the Audiovisual Archives Unit, Irene Lim, were extremely supportive of the idea of the AFA. It was a project that was aligned with NAS’ own heritage preservation mission. Things quickly fell into place: a referendum of understanding was drafted and NAS became an archiving partner. This partnership was essential because AFA finally had access to proper archival storage facilities and could function as a film archive.

In January 2005, the AFA decided to establish itself as an independent non-profit public company with limited guarantee. The AFA made a call for contributions and more than 200 film titles were collected within the first half of 2005. The AFA steadily garnered support from local and regional filmmakers and received positive press coverage. In March 2005, a working committee was formed to prepare for an Asian film symposium as well as to produce Singapore’s first DVD anthology of Singaporean short films – the Asian Film Archive Collection: Singapore Shorts Vol. 1.

The AFA has since grown from strength to strength, expanding its collection, engaging and educating the public and preserving Asia’s film heritage for future generations.

Thong Kay Wee is the Outreach Officer of the Asian Film Archive (AFA). One part publicist and one part curator, he is responsible for devising strategies to propagate the archive’s mission and film collection. In his free time, he considers himself an independent moving image artist.

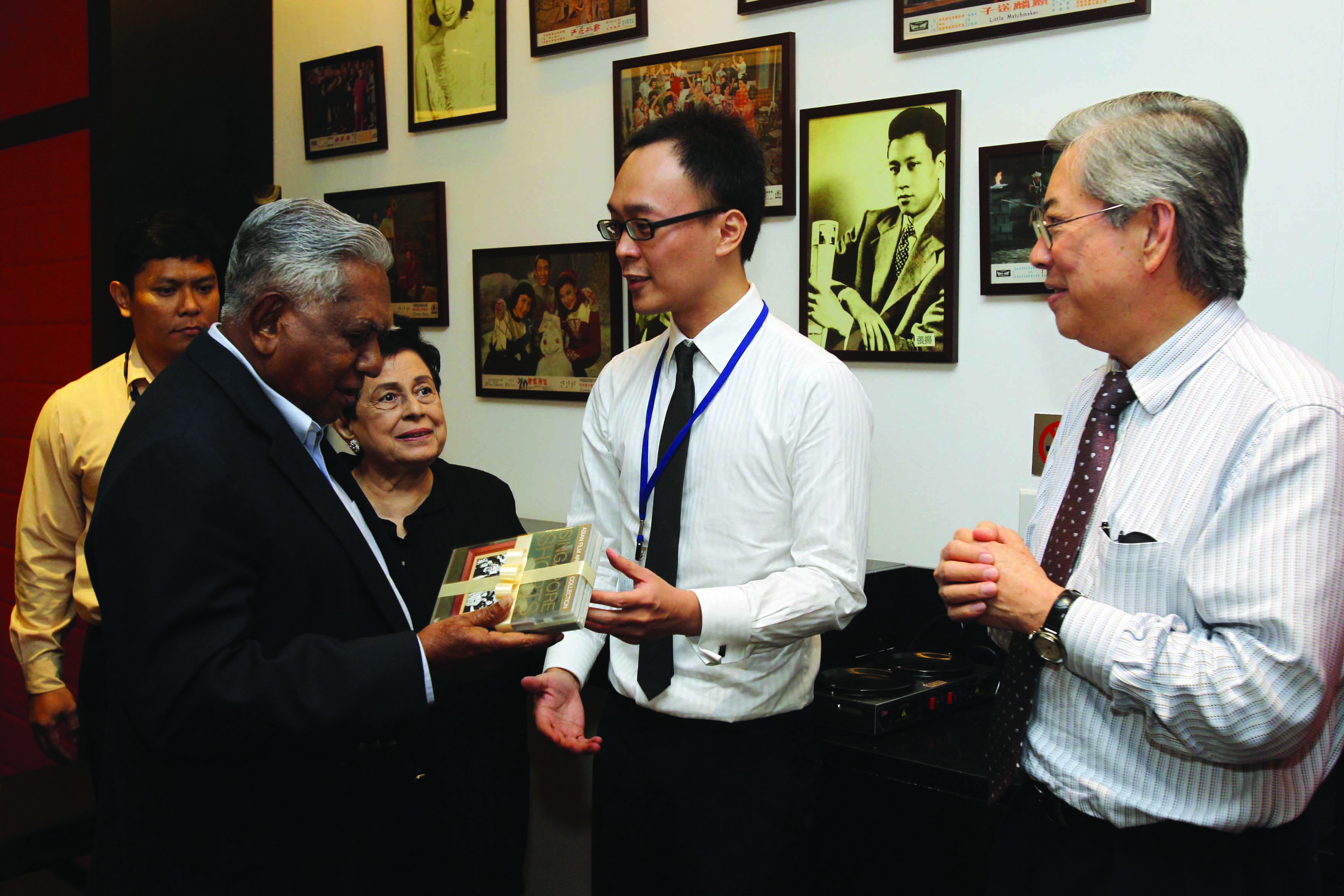

Tan Bee Thiam (right) presenting a token of appreciation to former president S.R. Nathan (left) in 2010. Courtesy of the AFA.

Tan Bee Thiam (right) presenting a token of appreciation to former president S.R. Nathan (left) in 2010. Courtesy of the AFA.

ABOUT THE AFA

The Asian Film Archive (AFA) is a charity that preserves Asia’s rich film heritage in a permanent collection focusing on culturally important works by independent Asian filmmakers. It promotes a wider critical appreciation of Asia’s cinematic works through organised community programmes, including screenings and talks.

AFA’s holdings include films of award-winning Filipino filmmakers such as Lino Brocka, Mike de Leon, Lav Diaz, and Malaysian filmmakers Amir Muhammad, U-Wei Haji Saari and Tan Chui Mui, among others. The Archive is also home to a collection of Cathay-Keris Malay Classics from the 1950s to 1970s that are part of the UNESCO Memory of The World Asia-Pacific Register, a list of endangered library and archive holdings.

The AFA’s collection is available for public reference at the library@ esplanade and through the AFA Channel on viddsee.com, an online portal that showcases the best of short films from Southeast Asia.

The AFA became a subsidiary of the National Library Board in January 2014.

10th anniversary logo of the Asian Film Archive.

10th anniversary logo of the Asian Film Archive.

THE 19TH SEAPAVAA CONFERENCE

Hosted by the AFA and supported by the National Library Board, Singapore, the 19th South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA) Conference and General Assembly will take place from 22 to 28 April 2015. The week-long event at the National Library Building will feature a two-day symposium with concurrent sessions, institutional visits, Restoration Asia II (an event focusing on the restoration of films in Asia or about Asia), workshops, and an excursion. A total of 48 papers will be presented during the conference on topics such as archival advocacy, archival repatriation, professional development, repurposing of archives, technical, organisational and professional sustainability, and archives at risk. For more information, visit www. seapavaaconference.com. The theme for the 2015 SEAPAVAA conference is Advocate. Connect. Engage. This theme resonates closely with the thrust of AFA’s programmes and the three objectives contained in its mission statement – “To Save, Explore, and Share the Art of Asian Cinema”.

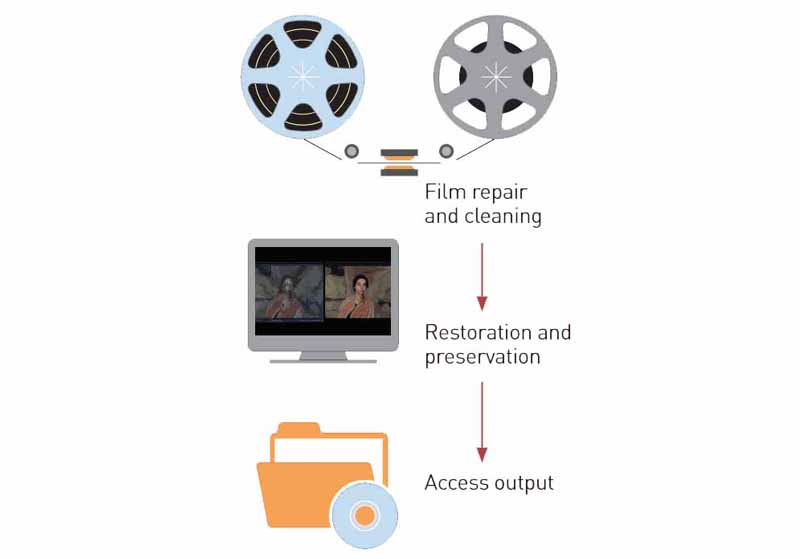

DIGITAL FILM RESTORATION

Digital film restoration is a highly specialised and laborious process. It involves the complex use of technological software and equipment that are designed to ingest huge amounts of data. The simplified workflow diagram below gives an idea of the three main parts of digital film restoration – repair and cleaning; restoration and preservation; and access output.

Karen Chan is Executive Director of the Asian Film Archive (AFA). Besides overseeing the growth, preservation and curation of the AFA’s collection, she teaches film literacy and preservation courses to educators, students and filmmakers. Karen also serves on the Executive Council of the South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archive Association.

REFERENCES

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Science and Technology Council. (2007). Digital dilemma: Strategic issues in archiving and accessing digital motion picture materials. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Asian Film Archive & National Archives of Singapore. (2005). AFA signs first MOU with the National Archives of Singapore. Retrieved from Asianfilm archive website.

Cherchi Usai, P. (2001). The death of cinema: History, cultural memory and the digital dark age. London: British Film Institue. (Call no.: 778.58 CHE).

Cherchi Usai, P. et al. (Eds.). (2008). Film curatorship: Archives, museums and the marketplace (p. 170). Österreichisches Filmmuseum: lSYNEMA–Gesellschaft für Film und Medien. (Call no.: 025.1773 FIL).

Edmonson, R. (2004). Audiovisual archiving: Philosophy and principle. Paris: Unesco. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Jones, J. (2012). The past is a moving picture: Preserving the twentieth century on film (p.9). Florida: University Press of Florida. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Kula, S. (2002). Appraising moving images: Assessing the archival and monetary value of film and video records. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. (Call no.: R 025.1773 KUL).

Kwok, Y. (2005, January 21). Archive alive. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lim, B.C. (2013, Spring). Archival fragility: Philippine cinema and the challenge of sustainable preservation. Newsletter, 67, 18–21.

Personal communication with Tan, B.T., 23 December 2014.

Tan, J. (2005, January 25). Film buffs to the rescue. Today, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Quote from South East Asia-Pacific Audiovisual Archives Association citation of Misbach Yusabiran as one of its founding fellows on its website. Seepavaa. (2010). SEAPAVAA honors contribution by leading archivists: Inaugural Fellows Circle. News Archive. Retrieved from Seapavaa website. ↩

-

This is the vendor’s template of VFI’s digitised library software platform 2014; UCLA Film & Television Archive. (2014). Vietnam Film Institute. Retrieved from UCLA Film & Television Archive website. ↩

-

The reels keep turning. (2014, September 5). Bangkok Post. ↩

-

Segay, J. (2007, February 26). Current audiovisual and cinema situation in Laos. Retrieved from ASEF CULTURE360 website. ↩

-

Panh, R, (2006). Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center. Retrieved from Bophana.org website. ↩

-

Nocon, C. R. (2011, October 27). Finally, a national film archive. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from INQUIRER.net website. ↩

-

Del Mundo, C.A. (2009). Dreaming of a national audio-visual archive (p. 4). Manila: Society of Film Archivists (SOFIA). (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Santiago, D.H. (2010). Interviewed for Saving face: Issues in film preservation and archiving. Santiago, M. ↩

-

Jones, J. (2012). The past is a moving picture: Preserving the twentieth century on film (p. 9). Florida: University Press of Florida. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

AFA’s collection guidelines and FAW section can be found on the AFA website. ↩

-

Jones, 2012, p. 126. ↩

-

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Science and Technology Council. (2007). Digital dilemma: Strategic issues in archiving and accessing digital motion picture materials (p. 2). Beverly Hills, Calif.: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Jones, 2012, p. 126. ↩

-

Kula, S. (2002). Appraising moving images: Assessing the archival and monetary value of film and video records. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. (Call no.: R 025.1773 KUL). ↩

-

Details on the campaign can be seen on the Asian film archive website. ↩

-

Publicity coverage in The Straits Times on the UNESCO inscription; Information about the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme can be found at Unesco mowcap org website. ↩

-

Cherchi Usai, P. et al. (Eds.). (2008). Film curatorship: Archives, museums and the marketplace (p. 170). Österreichisches Filmmuseum: ISYNEMA–Gesellschaft für Film und Medien. (Call no.: 025.1773 FIL). ↩

-

Cherchi Usai, 2008, p. 231. ↩