The Revival of Singapore Cinema: 1995–2014

Singapore’s film industry gets a reboot as it enters a new phase of its development. Raphaël Millet explains how this resurgence came about.

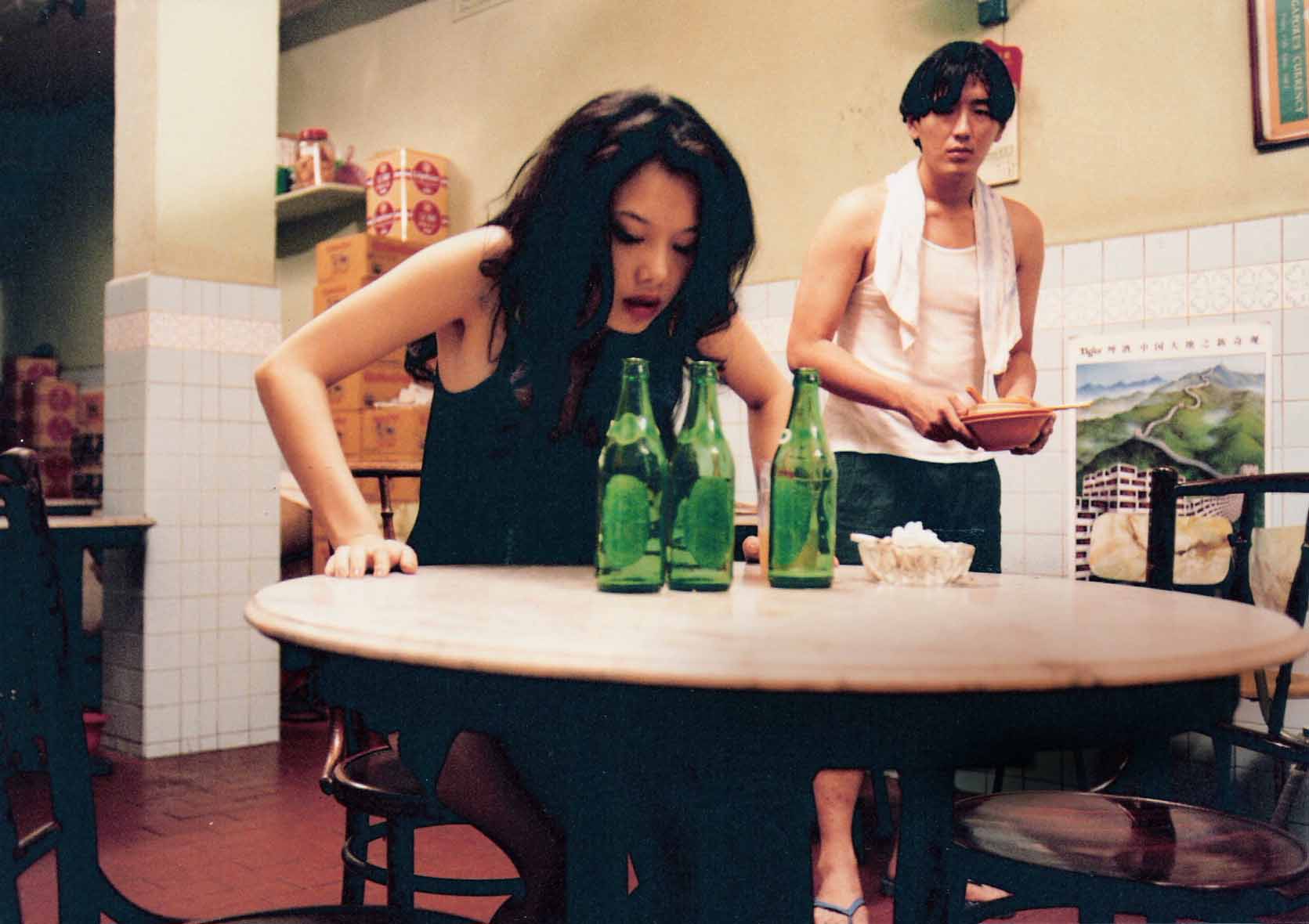

Film still from Eric Khoo's Mee Pok Man, which starred Michelle Goh and Joe Ng. © Mee Pok Man. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Jacqueline Khoo, distributed by Zhao Wei Films. Singapore 1995. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Film still from Eric Khoo's Mee Pok Man, which starred Michelle Goh and Joe Ng. © Mee Pok Man. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Jacqueline Khoo, distributed by Zhao Wei Films. Singapore 1995. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Is 2015 going to be a watershed year for Singaporean cinema? Two highly symbolic events have paved the way for it, and, when taken together, encapsulate the larger picture of Singaporean film history, from its origins at the turn of the 20th century until today.

Firstly, Run Run Shaw, co-founder in 1926 of the oldest Singaporean film empire, passed away in March 2014. His death – at age 106 – brought to full closure the first great cycle of Singaporean film history (largely predating the country’s Independence), and marks the passing of a bygone era of which he had been the last survivor.

Secondly, 2014 saw the return – after three years of inactivity – of the Singapore International Film Festival (SIFF) which, since its inception in 1987, has paved the way for what has been the gradual revival of a local film industry leading to its second historical cycle (coinciding with post-Independent Singapore). The hiatus of the festival between 2011 and 2013 was ominous, as there cannot be a serious film industry without a credible and established film festival. Fortunately, the SIFF, as it was known during its first 24 editions, is now back on track with a new acronym, SGIFF; its 25th outing in 2014 included a line-up of no less than 10 made-in-Singapore feature-length films. This is rather impressive, compared with the first few editions of the festival from 1987 to 1994 when there was very little local content to show as film-making in Singapore had ground to a halt.

The origins of the SIFF date back to 1987. In the absence of active filmmakers and producers, a small group of film buffs led by Geoffrey Malone (an Australian who had settled in Singapore in the early 1980s), with the help of two Singaporeans, Philip Cheah (who handled programming) and Teo Swee Leng (who took charge of administration) laid the foundations of the SIFF in 1987. The festival opened a new window for the expression and appreciation of the art of film, and effectively put in place part of the ecosystem needed for future film directors to emerge.

In its first few years, the SIFF saw itself as a bridge between generations, paying homage to the long-gone filmmakers of the golden age and celebrating Singapore’s film heritage. In doing so, the SIFF helped to nurture new talent in the film industry. An important step was taken in that direction when the festival introduced its very first Silver Screen Awards in 1991. Open to both Singapore and regional works of film, the awards spurred emerging local directors to showcase their productions.

The Rise of Auteur Cinema

The first glimmer of hope for the revival of local cinema appeared that same year when Eric Khoo’s August bagged the award for Best Singapore Short Film at the newly inaugurated awards. Encouraged by the award, Khoo successively directed a few more short films: Carcass (1992), which draws parallels between the life of a businessman and that of a butcher, and was the first local film to be given an R(A) rating; and Pain (1994), which recounts the story of a sado-masochistic young man, and won Khoo the Best Director and Special Achievement Awards at the 1994 edition of the festival. Unfortunately, Pain was banned from public viewing in Singapore because of its graphically violent scenes. These films marked the beginning of the great revival of Singaporean cinema.

It was only in 1995 that another major step was made, led again by Khoo, then 30-years-old, with the premiere of his first feature film, the seminal Mee Pok Man. Symbolically, the release of the film coincided with Singapore’s 30th anniversary of Independence. Khoo was to be a director of many firsts. If, when looking back, a movie were to be recognised as truly marking the revival of Singaporean cinema – the onset of the second historical cycle following that long coma – it would certainly be this movie. Locally produced, directed and acted, Mee Pok Man set in many respects the tone for a number of Singaporean productions that would follow in the next two decades. The film is pioneering because of its bleak social drama theme infused with angst-filled melancholy, but more importantly, it single-handedly revived the Singapore film industry. The feat is all the more amazing when one considers the fact that Mee Pok Man was able to blaze a trail of its own, with none of the baggage connected with the golden age of Singaporean cinema as embodied by the Shaw and Cathay studios of yesteryear. Endowed with all the traits of an indie production, the film is clearly the work of an auteur.

Mee Pok Man was the first Singaporean feature film to be entered for the SIFF’s Silver Screen Awards, and it was subsequently invited to over 30 international film festivals, including the Berlin and Venice festivals. The film effectively placed Singapore back on the map of world cinema.

Two years later, Khoo directed his second feature film, 12 Storeys, a social drama in the vein of Mee Pok Man but with a more intricate structure, unveiling the lives of four different families living in the same 12-storey block of flats (hence the title). Cleverly cross-cutting between the intertwined lives of the occupants, the film sheds a bleak light into the dark corners of a depressive and eventually destructive Singaporean society – not inured from unresolved anxieties despite having been carefully socially engineered by the authorities.

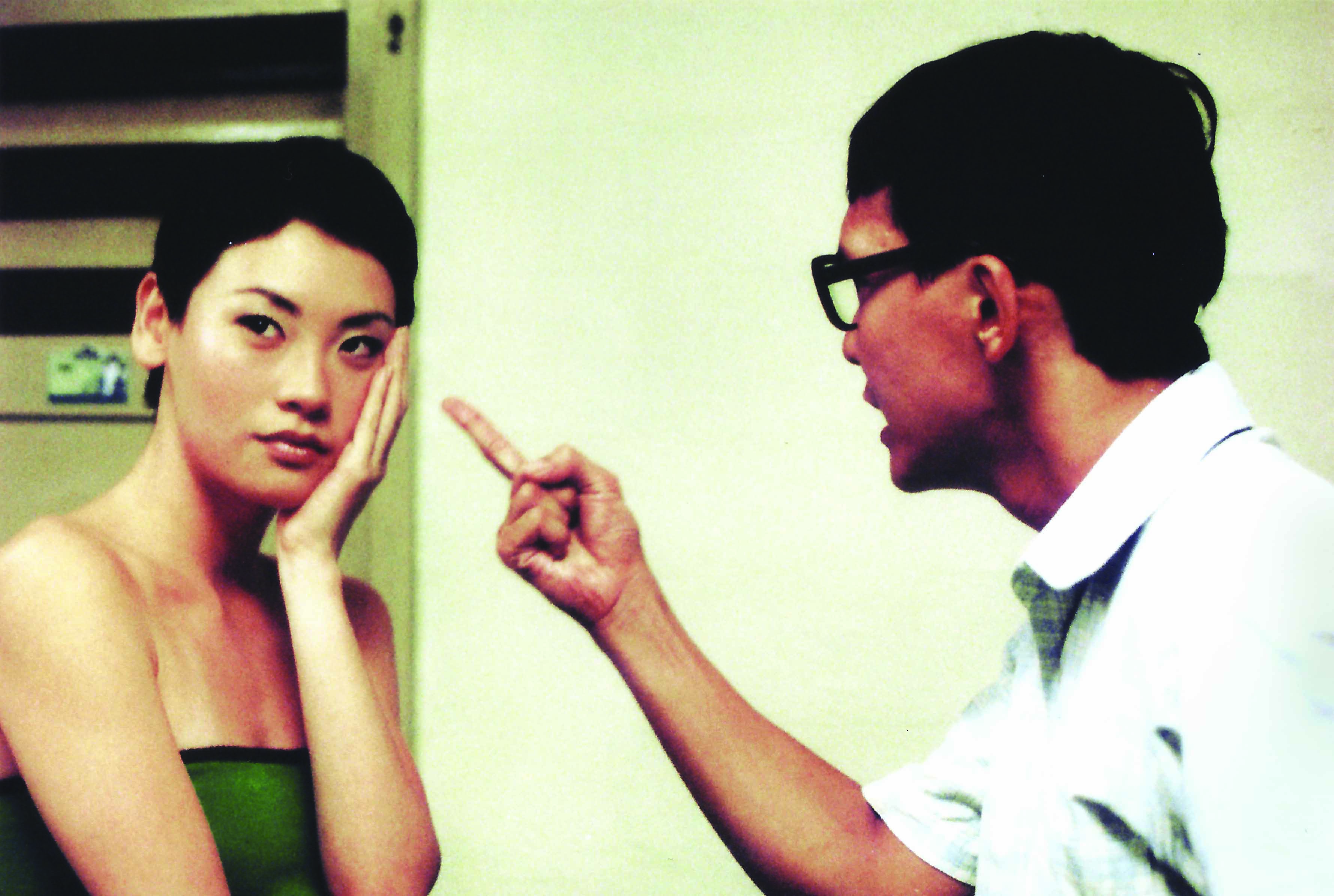

Lum May Yee (left) and Koh Boon Pin (right) in 12 Storeys. © 12 Storeys. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Brian Hong, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore 1997. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Lum May Yee (left) and Koh Boon Pin (right) in 12 Storeys. © 12 Storeys. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Brian Hong, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore 1997. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Always on the lookout for new talent, Eric Khoo offered Jack Neo his debut as a full-fledged cinema actor in 12 Storeys, something that was to have long term consequences on the development of Singaporean cinema (although in a different direction from what Khoo had undertaken). While Neo had already become famous on local TV for his comedic skills, 12 Storeys not only revealed his ability to be a big screen actor, but also showcased his ease for social drama. The film also showed Neo’s ability to underplay a role (something quite rare for him, and quite the opposite of what he would generally do afterwards). Neo’s exceptionally nuanced and intimate portrayal of Ah Gu’s character in the movie certainly remains his best cinematic performance yet. With 12 Storeys, Khoo asserted even further the role to be played by auteur cinema in representing, both locally and internationally, the identity of modern Singapore. Indeed, 12 Storeys was not only the second Singapore-made movie to be entered for the SIFF’s Silver Screen Awards, but also the first Singapore film to be screened at the Cannes Film Festival as part of its Un Certain Regard programme.

During the next few years, Khoo kept himself busy producing other people’s films, such as those of his then protégé Royston Tan, and only returned to direct another movie eight years later. The long-awaited Be With Me (2005) adopted the same artistic and thematic approach seen in 12 Storeys. This skillfully crafted movie spoke volumes about other unspoken sides of Singapore (such as lesbianism), and was produced right in time for the 40th anniversary of the country’s Independence.

Be With Me launched the second decade of the revival of Singaporean cinema, spanning the period 2005 to 2014. By this time Singaporean cinema was alive and kicking, and Khoo proved that he was still a talent to be reckoned with. Be With Me premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight section in the 2005 Cannes Film Festival, another first for Singapore. In the years that followed, Khoo remained a major proponent of Singapore arthouse cinema, with two new opuses in which he managed to renew and refresh his approach to film: My Magic (2008) and Tatsumi (2011).

With My Magic (2008), Khoo unexpectedly focused on the Tamil minority, shooting in Tamil, with a largely Tamil cast. It tells the heartbreaking story of a young boy and his father, a former magician. In spite of its limited acting range, largely due to the fact that the lead character was played by a non-professional actor, and the film appeared “rushed and improvised on all technical fronts” as some international media rightfully remarked, it was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival – once again a first for a Singaporean film. But in the end, My Magic did not win, perhaps precisely because of its acting and technical shortcomings, as well as for its overly sentimental plot.

In 2011, Khoo released what might be seen as a far more daring and refreshing film, Tatsumi, an animated film inspired by the works of renowned Japanese manga artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Set in Japan with full Japanese dialogue, Khoo dramatically departed from what has been hitherto perceived as a “Singaporean movie”, thus raising many interesting issues in terms of what contributes to the identity of a national cinema. With Tatsumi – which featured exquisitely executed animation and was lauded by critics the world over for its beautiful graphics and excellent music score – Khoo proved that good cinema went beyond geographical borders and that Singaporean filmmakers did not have to confine themselves to filming stories set in HDB flats or shopping malls.

Tatsumi deservedly gained international recognition when it premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. Yet, as with Khoo’s previous Cannes’ nominations, it did not win, and this once again tempered his achievements. A further setback was in store: although the film was selected as the Singaporean entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 84th Academy Awards, it did not make it to the final shortlist of nominated movies.

Eric Khoo (centre) during the production of Be With Me. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Eric Khoo (centre) during the production of Be With Me. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Film still of Eric Khoo's Tatsumi, a film inspired by the works of manga artist, Yoshihiro Tatsumi. © Tatsumi. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Tan Fong Cheng, Gary Goh, Phil Mitchell, Freddie Yeo, Eric Khoo and Brian Gothong Tan, distributed by Golden Village Pictures and Happiness. Singapore, 2011. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Film still of Eric Khoo's Tatsumi, a film inspired by the works of manga artist, Yoshihiro Tatsumi. © Tatsumi. Directed by Eric Khoo, produced by Tan Fong Cheng, Gary Goh, Phil Mitchell, Freddie Yeo, Eric Khoo and Brian Gothong Tan, distributed by Golden Village Pictures and Happiness. Singapore, 2011. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

In spite of these minor setbacks, Khoo’s contribution to the revival of Singaporean cinema is not diminished. He set the direction and the standards for an auteur cinema where an independent director’s personal creative vision is paramount, free from the stresses of commercial goals or worries.

Djinn Ong’s career, although very promising, was largely short-lived, with only two feature films to his directorial credit. Return to Pontianak (2001) was Singapore’s first attempt at revisiting the horror film genre left fallow since the early 1970s (some of Ong’s peers, like Kelvin Tong, would explore this genre a few years later). Ong’s second film, Perth (2004) tells the story of Harry Lee, a security supervisor at a shipyard who, after losing his job due to brutal downsizing, is forced to become a driver in order to make a living, with hopes of one day retiring in Australia.

Unfortunately, Ong discontinued his filmmaking work partly due to personal reasons and did not have a chance to take part in the second decade of the Singaporean cinema revival from 2005 to 2014 – a pity, as Perth had a grittiness rarely seen until then in Singapore films, and still stands out precisely for this.

Lim Kay Tong in Perth: The Geylang Massacre. © Perth: The Geylang Massacre. Directed by Djinn Ong, distributed by Tartan Films. Singapore, 2004.

Lim Kay Tong in Perth: The Geylang Massacre. © Perth: The Geylang Massacre. Directed by Djinn Ong, distributed by Tartan Films. Singapore, 2004.

Royston Tan and Kelvin Tong opted for more hybrid careers, oscillating between the desire of being perceived as ambitious arthouse auteurs and the temptation of trying their hand – although not always with great success – at commercial cinema, the other avenue increasingly open to local filmmakers.

Royston Tan, for instance, has moved from the controversial 15 (2003) to the bleak Eric Khoo-inspired 4:30 (2005), before delving into the blatantly commercial and artistically kitsch 881 (2007). While 15 was heavily censored due to its graphic portrayal of teenage gangsterism (the film had to undergo numerous cuts before it was eventually released) 881 was a boisterous musical comedy – interspersed with occasional dramatic moments – and went on to become a box-office hit. In doing so, Tan has gone from one extreme end of the spectrum to the other, blurring the lines of his directional style in the process. The only constant has been his predilection for movie titles with numbers. His last feature film, 12 Lotus (2008) is his most mature work so far, finding the right balance between a good drama and a fun, easy-going film.

Royston Tan's 881 explores the colourful world of getai. © 881. Directed by Royston Tan, produced by Gary Goh, James Toh, Chan Pui Yin, Freddie Yeo, Tan Fong Cheng and Ang Hwee Sim, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2007.

Royston Tan's 881 explores the colourful world of getai. © 881. Directed by Royston Tan, produced by Gary Goh, James Toh, Chan Pui Yin, Freddie Yeo, Tan Fong Cheng and Ang Hwee Sim, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2007.

The Rise of Commercial Cinema

At the exact opposite end of Eric Khoo on the spectrum of Singaporean film genres stands Jack Neo. He is the other notable film director in the last two decades with a body of work even superior in quantity – but perhaps not in quality, although a comparison might not be really valid here – to the work of Khoo.

Jack Neo started off as a multitalented TV entertainer, and then went on to act in film (debuting in Khoo’s 12 Storeys) before becoming a prolific director, often acting in his own movies. All along Neo remained active in television and successfully retained a large popular base, which in turn benefited his ventures into film – at least commercially, if not always artistically. Indeed, Neo quickly became the most profitable (“bankable”, some would say) director in the Singaporean movie industry, almost continuously dominating the local box office for close to 20 consecutive years with his highly popular comedies.

Neo’s first venture into this genre was the 1998 Money No Enough, which he did not direct himself but instead wrote and played the lead of a middle-class Chinese Singaporean who does not speak fluent English nor have high educational qualifications and who faces difficulties at work. With Mark Lee playing the role of a contractor in debt to loan sharks and Henry Thia as a coffeeshop waiter obsessed with girls, Neo managed to intertwine personal stories of men caught in everyday troubles, but in a far less subtle (but far more hilarious) way than Khoo’s nuanced and multilayered melancholic style. The Singaporean audience loved it, and the film was such a runaway success that it became the top-grossing movie ever in the country, a title it kept for about 13 years. Money No Enough shot Jack Neo to immediate cinema stardom and gave the Singapore film industry a gigantic – and much needed – boost.

The hapless misadventures of the comic trio in Money No Enough became one of Neo’s trademarks, soon recycled in 1999 in both Liang Po Po – The Movie (which, again he wrote but did not direct) and That One No Enough (which, finally, he directed). In both films, Neo poked fun at Singaporeans’ idiosyncrasies. Once again, Singaporeans loved it, and both movies were box-office hits, even though they did not break Money No Enough’s record.

Mark Lee (left) and Jack Neo (right) in 1998's Money No Enough. Directed by Tay Yeck Lock, produced by JSP Films, distributed by Shaw Organisation. Singapore, 1998. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

Mark Lee (left) and Jack Neo (right) in 1998's Money No Enough. Directed by Tay Yeck Lock, produced by JSP Films, distributed by Shaw Organisation. Singapore, 1998. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

I Not Stupid starred Joshua Ang (left) and Shawn Lee (right) in 2002. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Mediacorp Raintree Productions, distributed by United International Pictures, Singapore, 2002. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

I Not Stupid starred Joshua Ang (left) and Shawn Lee (right) in 2002. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Mediacorp Raintree Productions, distributed by United International Pictures, Singapore, 2002. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

With That One No Enough, Neo embarked on a directing career that turned him into Singapore’s most prolific filmmaker, directing a total of 18 feature films within 16 years (from 1998 to 2014). Some critics found him a bit too prolific to be consistently good all the time, and it is true that some of his comedies were not as commercially successful – sometimes because they were just not as funny as his previous efforts. The truth is that making people laugh is far more difficult than making people cry – be it when writing a book, staging a play or directing a movie. So far, despite his highs and lows, Neo has done a pretty good job at making Singaporeans laugh at themselves, something much needed for the morale and psychological sanity of a nation not often known for its self-deprecating humour.

Neo has humorously addressed major local issues such as the irresistible drive for money (That One No Enough), its fascination with gambling (The Best Bet), the pressure-cooker education system (I Not Stupid), National Service as a rite of passage (Ah Boys to Men), and others. As a matter of fact, Neo’s strength lies in having his finger right on Singapore’s pulse, knowing what his fellow Singaporeans are currently obsessing over, while at the same time managing to keep it just within a hair’s breadth of the perceived out-of-boundary markers in Singapore society. If you can be sure about one thing about Neo, it is that he knows his OB markers. This is one of the primary reasons for his commercial success at filmmaking.

Yet, Jack Neo’s main shortcomings as a filmmaker are to be found in the all too often poor production value of his movies. Indeed, many are no more than telemovies projected onto the big screen, sometimes unconvincingly (if not badly) acted, sometimes technically lame, as in the case of I Do I Do, The Best Bet, and Lion Men. This is most regrettable as Neo is talented and can do much better when he sets his mind to it, something he has proven with I Not Stupid (2002), and even more so with Homerun (2003).

Although Homerun re-casted some of the children who acted in I Not Stupid, the film departed from Neo’s usual style and displayed, for the first time, true artistic ambition on his part as a director. A remake of Iranian Majid Majidi’s critically acclaimed arthouse movie Children of Heaven (1997), Homerun – transplanted into the Singapore landscape – explored new territory by being the first large-scale period movie to be made locally. But instead of re-staging the major political and social events that shook Singapore in 1965, it placed them in the background of a main plot that focused on a brother and sister from a poor family. Well crafted (with carefully selected locations in neighbouring Malaysia giving the movie an air of authenticity), it was most of all superbly acted by some very promising young actors. Deservedly, one of its leads, 10-year-old Megan Zheng, won the Best New Performer Award at the 40th Golden Horse Film Festival, clinching the first ever Golden Horse Award for Singapore. With this win, Neo had proven that Eric Khoo was not the only one to be counted on when it came to “firsts” in terms of international recognition. This was a major success for Singapore’s revived cinema industry.

Shawn Lee (left) and Megan Zhang (right) in Homerun, a re-make of Majid Majidi's Children of Heaven. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Chan Pui Yin and Titus Ho, distributed by Mediacorp Raintree Pictures. Singapore 2003. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

Shawn Lee (left) and Megan Zhang (right) in Homerun, a re-make of Majid Majidi's Children of Heaven. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Chan Pui Yin and Titus Ho, distributed by Mediacorp Raintree Pictures. Singapore 2003. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

Curiously, following Homerun’s success, Neo went back to his previous low production value films, with The Best Bet (2005), I Do I Do (2006) and Just Follow Law (2007), generally churning them out in time for release at Chinese New Year. But Neo soon entered the second decade of the Singaporean film revival with a new strategy that proved rather fruitful: he started making sequels to his previous successes, while at the same time creating new movies conceived as franchises to reap greater economies of scale.

The first sequel was I Not Stupid Too in 2006, revisiting more or less the same story four years after the first film. Following the same vein, Neo also directed Money No Enough 2, exactly a decade after the original, once again poking fun at his fellow Singaporeans still engaged in an endless pursuit of money. The sequel recipe proved lucrative, with I Not Stupid Too beating its predecessor at the box office, and Money No Enough 2 coming very close to the record gains of his 1998 Money No Enough.

In 2012, Neo finally surpassed himself with Ah Boys to Men, earning more than S$6 million domestically, something absolutely unheard of until then. A year later, in 2013, this record was beaten by Ah Boys to Men 2, which made S$7 million at the local box-office. The Ah Boys to Men franchise, perhaps the first of its sort in the history of Singaporean cinema, dealt with the misadventures of a group of young army recruits doing their National Service, something which has always been a source of great bonding and joshing around among Singaporean men. That same theme had already been brought to screen in the form of a comedy as early as 1996 with Ong Ken Sen’s Army Daze. The film had been a relative success then, but nothing compared to Neo’s box-office tsunami.

Looking back at Jack Neo’s accomplishments over the last 15 years or so, it would appear that he has almost singlehandedly created locally made commercial films that can make a windfall. But the truth is that Neo, alone, has almost entirely occupied that space. Many have tried to copy Neo in the hope of replicating his success, but this has generally been in vain. Jack Neo’s recipe for box-office success is a closely guarded secret.

A film still from Ah Boys to Men. © Ah Boys to Men. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Jack Neo, Lim Teck and Leonard Lao, distributed by Golden Village Pictures & Clover Films. Singapore, 2012. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

A film still from Ah Boys to Men. © Ah Boys to Men. Directed by Jack Neo, produced by Jack Neo, Lim Teck and Leonard Lao, distributed by Golden Village Pictures & Clover Films. Singapore, 2012. Courtesy of J Team Productions.

A New Generation with Potential

In the second decade of the revival, a new generation of filmmakers, some of them owing very little to either Eric Khoo or Jack Neo, has emerged. There are too many of them to name, but four – Ho Tzu Nyen, Boo Junfeng, Anthony Chen and Ken Kwek – stand out, largely because of the distinctive intrinsic qualities of their works.

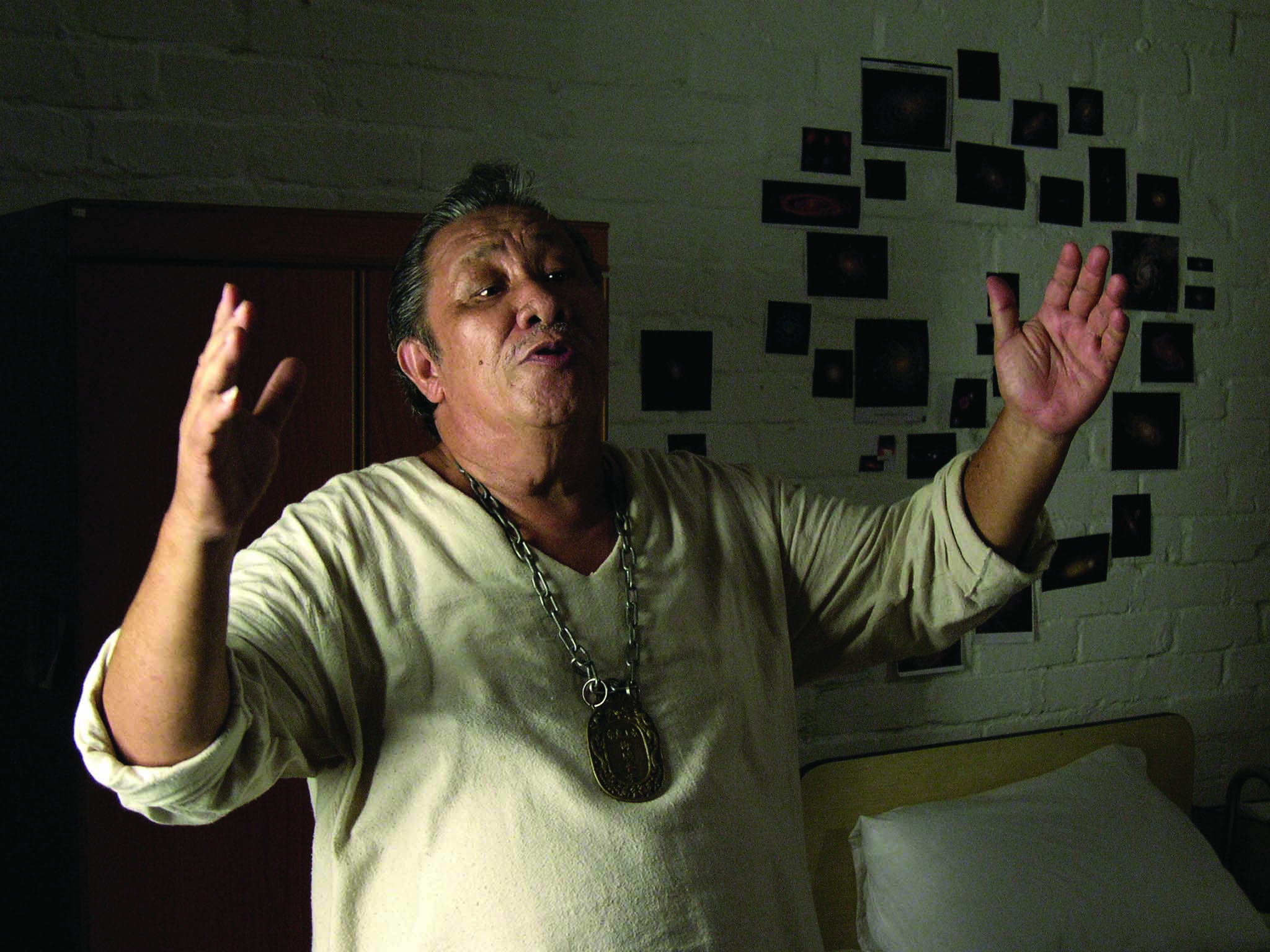

Ho Tzu Nyen is not just a filmmaker. He is one of Singapore’s most versatile multidisciplinary artists, approaching art first and foremost in terms of multimedia. For him, cinema is just one means of expression among the variety of multimedia works he excels in. One of Ho’s seminal breakthrough works was Utama – Every Name in History is I (2003), which consisted of a video and 20 portrait paintings, cleverly playing with the founding narratives of Singapore. He completed his first, and so far only feature film, HERE in 2009. This allegorical film shot in a mock-documentary style is set in a mental institution (the Island Hospital), where a traumatised man is forced to adjust to life in this confined place while undergoing experimental treatment. Beneath the surface, the Island Hospital is an obvious metaphor for Singapore, and the entire film is a grim and rather frightening commentary on the excesses of social engineering. HERE was selected for screening at the 41st Directors’ Fortnight section at Cannes in 2009.

In 2010, another young Singaporean director, Boo Junfeng, completed his first feature film, Sandcastle. Boo is not entirely new to the film scene as he has had a series of notable short films to his credit, such as Katong Fugue (2007), Keluar Baris (2008) and Tanjong Rhu (2009). But his debut feature took him to another level when it became the first Singaporean film to be invited to the prestigious International Critics’ Week at the 2010 Cannes International Film Festival. Sandcastle, produced by Eric Khoo’s company Zhao Wei Films, tells the story of an 18-year-old boy who finds out, through his grandparents, that his father who died of cancer a few years earlier, was once part of a group of political activists in the early years of Singapore’s Independence. This leads the young man on the brink of adulthood to reassess the official history of his country, and to reflect on the lack of idealism in a society driven mainly by pragmatism. Clearly, this is another bold commentary on Singapore’s societal, political and historical journey.

Bobbi Chen and Joshua Tan in Boo Junfeng's 2010 Sandcastle. © Sandcastle. Directed by Boo Junfeng, produced by Fran Borgia & Gary Goh, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2010. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

Bobbi Chen and Joshua Tan in Boo Junfeng's 2010 Sandcastle. © Sandcastle. Directed by Boo Junfeng, produced by Fran Borgia & Gary Goh, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2010. Courtesy of Zhao Wei Films.

The late Chuen Boone Ong in his role as Monsters Man in Ho Tzu Nyen’s 2009 HERE. Directed by Ho Tzu Nyen, produced by Fran Borgia, Michel Cayla and Jason Lai, distributed by Cathay-Keris Films (Singapore). Singapore, 2009. Courtesy of Ho Tzu Nyen.

The late Chuen Boone Ong in his role as Monsters Man in Ho Tzu Nyen’s 2009 HERE. Directed by Ho Tzu Nyen, produced by Fran Borgia, Michel Cayla and Jason Lai, distributed by Cathay-Keris Films (Singapore). Singapore, 2009. Courtesy of Ho Tzu Nyen.

Similarly, Anthony Chen honed his filmmaking skills through a variety of short films that have always displayed great potential, as seen in his first film, G-23 (2004), Ah Ma (2007) and Haze (2008). Chen’s debut feature film Ilo Ilo (2013) chronicled the difficult adjustments a Singaporean family has to make when they hire a Filipino maid – until they have to let her go when the Asian financial crisis in 1997 hits them hard. The movie met with considerable success when it was featured at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes 2013, and went one step further than any other Singaporean film had accomplished so far by winning the coveted Caméra d’Or at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, and four awards at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards the same year: Best Feature Film, Best New Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress.

Interestingly, although Ilo Ilo is the first and so far the only Singaporean win at Cannes, it initially received a conflicted review from a Singaporean film critic disturbed that recognition for the film should come from abroad first. This is altogether not unexpected; winning an international film award prior to being feted in the domestic market is a common phenomenon in the film industry, and the accolades the film has received are definitively something to be proud of. Moreover, Ilo Ilo fared reasonably well at the domestic box-office, proving that even local arthouse movies can sometimes be commercial successes in Singapore.

Finally, in late 2014, a new film director emerged in the person of Ken Kwek, with his debut feature Unlucky Plaza (2014) – the title a provocative metaphor of modern Singapore. Kwek had already been on the radar for his more controversial Sex. Violence. Family Values (2012) that was banned in Singapore. Fortunately, Unlucky Plaza did not suffer the same fate and was chosen to open the reborn SGIFF. The film’s strength lies in the fact that it managed to bring together all the things that make for a good independent arthouse film as well as the characteristics of what are usually perceived to be the hallmarks of a successful commercial movie. Intertwining destinies – the naive entrepreneur, the ubiquitous property agent, the loan shark, etc. – in a manner reminiscent of both Eric Khoo’s and Jack Neo’s styles, Unlucky Plaza portrays Singapore as a city-state devoured by greed in more ways than one. The film cleverly pulls it off by permanently oscillating between an irresistibly funny comedy and a riveting drama on society.

Angeli Bayani and Jieler Koh in Ilo Ilo. © Ilo Ilo. Directed by Anthony Chen, produced by Ang Hwee Sim, Anthony Chen, Wahyuni A Hadi, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2013.

Angeli Bayani and Jieler Koh in Ilo Ilo. © Ilo Ilo. Directed by Anthony Chen, produced by Ang Hwee Sim, Anthony Chen, Wahyuni A Hadi, distributed by Golden Village Pictures. Singapore, 2013.

Adrian Pang in Unlucky Plaza. Directed by Ken Kwek, produced by Ken Kwek, Kat Goh and Leon Tong. Singapore. 2014. © Kaya Toast Pictures.

Adrian Pang in Unlucky Plaza. Directed by Ken Kwek, produced by Ken Kwek, Kat Goh and Leon Tong. Singapore. 2014. © Kaya Toast Pictures.

What the Future Holds

As Singapore prepares to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its Independence in 2015, so too is Eric Khoo; he was born in 1965 and will celebrate his own 50th birthday this year. This conjunction of dates is highly symbolic as Khoo is the person who has almost singlehandedly sparked the revival of Singaporean cinema. Although Khoo remains one of the leading lights of local film, he is not as isolated as he was when he first started his career because several other filmmakers of note have emerged over the years.

If Khoo spearheaded what could be hailed as the first wave of directors from 1995 to 2004 and was immediately followed in this path by Jack Neo, Djinn Ong and Kelvin Tong, among others, one certainly cannot ignore the second wave of younger directors from 2005 to 2014. Filmmakers such as Boo Junfeng, Anthony Chen and, most recently, Ken Kwek, have pushed Singaporean cinema into new directions and brought local film to new levels of domestic and international recognition.

Let us go back to the question that was raised at the start of this essay: Is 2015 set to mark the start of a new decade of greater achievements for Singaporean cinema? The potential is there, and the ecosystem that makes it possible for a film industry to exist and thrive is now largely in place, unlike what it was like 15 or even only 10 years ago. Film studies are more prevalent in Singapore thanks to an efflorescence of film schools. Government support is also accessible for the most part, covering some of the essential steps needed for a film to materialise, from scriptwriting to development, and production to distribution.

Yet, the Singaporean film industry, after lying dormant for so many years, has had to start from ground zero, and is therefore still a fledgling one. The truth is that apart from Jack Neo, Eric Khoo, Royston Tan and Kelvin Tong, very few currently active directors have had the experience of making more than two or three features in their entire careers. Even filmmakers like Glen Goei, who started directing as early as the mid-1990s, found it difficult to go beyond their second feature film. After Forever Fever (1997) and Blue Mansion (2009), there was another long drought in Goei’s work in film until he recently began work on his remake of Pontianak – his homage to Singapore’s golden age of Malay filmmaking from 1947 to 1972. Pontianak is due for release in 2017.

Furthermore, with the exception of some of Neo’s blockbusters, the domestic film market is still not financially sustainable. After years of selections and nominations, Singapore films have only recently started winning international accolades, as in the case of Anthony Chen’s Ilo Ilo. Many challenges still await the local film industry, which, after surviving a near comatose period in the 1980s, is slowly coming back to life. If the stars are all aligned, Singapore cinema might finally be on its way to a true renaissance.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for cinema the world over. He divides his time between France and Singapore, and has published two books about Singaporean cinema, one in French in 2004, the other in English, simply titled Singapore Cinema, in 2006.

REFERENCE

Millet. R. (2006). Singapore cinema. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL)

Tan, K.P. (2008). Cinema and television in Singapore: Resistance in one dimension. Leiden: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 TAN)

Uhde, J., & Udhe, Y.N. (2010). Latent images: Film in Singapore. Singapore: Ridge Books. (Call no.: RSING 384.8095957 UHD)