Money-making Bodies: Prostitution in Colonial Southeast Asia

The oldest profession in the world took on a different complexion in Southeast Asia when the European colonial powers arrived. Farish Noor puts the pieces together.

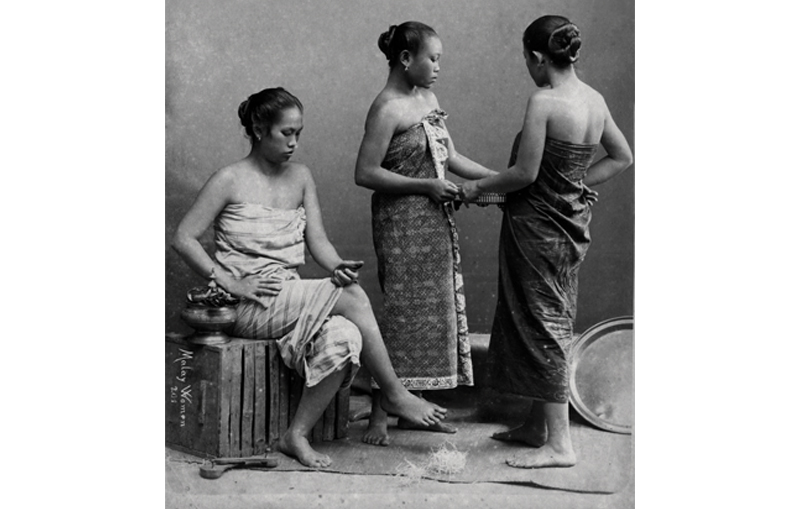

Three Malay women having their picture taken by G. R. Lambert & Company. Gustave Richard Lambert was a native of Dresden, Germany, who set up a photo studio in Singapore in 1867. His vast collection of prints depicting people and scenery provide a comprehensive photographic documentation of early Singapore. Image reproduced from Fotoalbum Singapur (1890). Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B18975148J).

Three Malay women having their picture taken by G. R. Lambert & Company. Gustave Richard Lambert was a native of Dresden, Germany, who set up a photo studio in Singapore in 1867. His vast collection of prints depicting people and scenery provide a comprehensive photographic documentation of early Singapore. Image reproduced from Fotoalbum Singapur (1890). Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B18975148J).

Southeast Asia has become an emblem of all that is exotic and colourful, and this is particularly true of the manner in which the region has been depicted in popular fiction and films for the longest time. This holds true for Singapore as well, which has been featured time and again in pulp fiction and popular films where the city is invariably presented as a steamy den of ne’er-do-wells and steamier bathhouses.

That these tropes recur time and again in literature and films has something to do with the residual memory of what Singapore – like many other cosmopolitan Southeast Asian commercial centres that developed in the 19th century – once was, and how it was regarded more than a hundred years ago. Today, Singapore is one of the world’s foremost commercial hubs, and is placed alongside other major cities as a favoured business destination for globe-trotting expatriates and entrepreneurs. Little did the founder of modern Singapore Stamford Raffles realise this when he stepped ashore the island on 28 January 1819. At Raffles’ behest, Singapore was acquired by the British East India Company and turned into a major entrepot centre for international trade. The rest, as they say, is history.

In Search of Profit and Markets

But another aspect of Singapore’s past that has been forgotten is how international trade was conducted in the 19th century, and the character of militarised commercial entities such as the British East India Company and its Dutch counterpart, the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India Company) that have no equivalent today. These were commercial entities that were given the power to acquire territory in the name of their respective countries, and to project military power across the globe in the search for profit and markets. In the course of doing so, these militarised commercial behemoths permanently altered the socio-economic landscape of the territories that came under their dominion, and in many ways laid down the foundations for what would later become the postcolonial nation-states of Asia that we know today.

Singapore was one of several cosmopolitan commercial centres that emerged during the colonial era, along with Georgetown (Penang) and Malacca in Malaya; Batavia (Jakarta), Medan and Surabaya in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia); and Manila in the Philippines. These commercial-administrative centres were somewhat unique in the way they performed several functions at the same time: Singapore, Georgetown and Batavia were bustling ports and administrative centres as well as military bases, and developed rapidly as a result of mass migration that was brought about by the advances in communications technology and logistics.

Unidentified upper-class 19th-century Eurasian family in Singapore. In the colonised Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), India, Philippines, Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang and Malacca) and elsewhere, European men took on Asian wives, giving rise to a distinct race of Eurasians who enjoyed a privileged place in society. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Unidentified upper-class 19th-century Eurasian family in Singapore. In the colonised Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), India, Philippines, Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang and Malacca) and elsewhere, European men took on Asian wives, giving rise to a distinct race of Eurasians who enjoyed a privileged place in society. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

It would be erroneous to think of these places as being completely dominated by Europeans, for in reality most of these colonial centres relied on Asian migrant labour at almost every level of the hierarchy: in the mines and fields, in the ranks of the local militias and guard units, and in the byzantine hive of colonial administration. David Joel Steinberg and others (1985) have noted that Batavia – which was the centre of Dutch colonial power across the entire East Indies – had at most a few thousand Europeans serving in its elite administrative corps, while much of the work of governance and commerce was handled by multitudinous Asians, both locals and migrants.

Here, it is crucial for us to remember one other fact that seems to have passed unnoticed: that racialised colonial-capitalism in the 19th century was almost entirely a male-dominated affair, and most of the bureaucrats, functionaries and soldiers who worked with and under the colonial companies were men. And it is also true that many of the Asian immigrants who were shipped to Southeast Asia from India and China were men as well. The net result of this male-biased mass migration to colonies like Singapore was the emergence of a distinctly male-dominated homosocial environment.

The fact that the colonial service, the colonial companies, the colonial security forces and the local economy were staffed mostly by men created one of the most awkward situations that the colonial system had to face: how to maintain some semblance of social order and cohesion in what appeared to be a lopsided society in domains where there were more men than women.

In India, the British East India Company had addressed the problem by allowing members of the Anglo-Indian colonial service and armed forces to take local brides, (or in some cases engage in illicit liaisons) giving rise to what would later become the Anglo-Indian Eurasian class whose descendants can be found in India until today. The Dutch in the East Indies had also allowed Dutchmen to marry women from Java, Sumatra and other parts of the archipelago, giving rise to the Indo class of Eurasians who were of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, similar to their Mestizo counterparts in Spanish-ruled Philippines. In most of these societies, such Eurasians were viewed by the local population with equal measures of awe and disdain as they were accorded privileges that other Asians did not enjoy because of their partly European lineage.

Singapore was governed in quite a different manner, and after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, Singapore, Malacca and Penang came under British rule and would later be integrated as the Straits Settlements in 1826. (Singapore was made the capital of the Straits Settlements in 1832, and remained so until the Settlements became a Crown Colony in 1867.)

In Singapore and Penang, a new kind of social experiment was due to take place as large numbers of male Asian immigrants from China and India were brought to the colonies and eventually settled in neatly compartmentalised ethnic-based enclaves that until today are referred to as “Chinatown” and “Little India” in these cities. Emerging as they did during the era of racialised colonial-capitalism where a racial hierarchy between whites and Asians was clearly, and painfully, visible, the other problem that had to be dealt with was how to placate the natural sexual urges and inclinations of so many men – Europeans and Asians alike – in a rapidly growing colony where women were relatively scant in number. The answer was simple: legalised prostitution.

Race, Gender and the Commodification of Women

James Warren (1990) has noted that among the areas that remain woefully under-researched in the domain of Southeast Asian Studies, the lives of ordinary, poor working-class Asian women ranks high on the list of forgotten histories. Though work has been done in terms of recording the history of male Asian labourers and migrants, the lives of Asian women migrants have gone largely unnoticed, not least for the reason that a significant number of the women who resided in the lowest strata of colonial society were also engaged in work that was deemed controversial or at least problematic until today.

Yet it cannot be denied that racialised colonial-capitalism, as a male-dominated enterprise, was dependent on women who served the colonial economy and society in other ways, including as sex workers in what was then regarded as a necessary evil – in the same way that the sale of opium was one of the ways through which European companies managed to break into the local Asian markets and expand their commercial activities across the region.

Singapore was no exception to the rule, and though few may realise it today, during the 19th century, Singapore’s reputation as a vibrant commercial centre was matched only by its reputation as a fleshpot that appealed to the libidos of both Western and Asian men. While male migrant workers and entrepreneurs were deemed necessary for the economic development of the colony, procuring Asian women and bringing them to the colony to serve as sex workers was matter-of-factly regarded as something normal and acceptable by the standards of the day. The trade in opium and sex was part and parcel of international commerce in the 19th century, and it was upon these practices that the fortunes of many people were later built. Singapore, like Georgetown, Batavia, Surabaya and other cosmopolitan commercial centres in Southeast Asia, was rife with prostitutes and brothels where both sex and opium were freely available in return for cash.

Yet, even in the case of the legalised sex trade then, racial hierarchies and distinctions were kept intact; and this fact also explains how and why the “red light” areas of Singapore were racially segregated, as Warren notes in detail:

“Each of the districts with hundreds of brothels lining streets cheek by jowl had their local clients. During the first part of the [20th] century Europeans – diplomats, officials and planters – favoured the discreet Japanese women of Malay and Malabar streets. Foreign tourists, soldiers, and, especially Japanese sailors also sought their sexual favours by visiting the unregistered haunts of Malay and Eurasian women scattered in the side lanes and alleys of the city. Rickshawmen made regular journeys to the brothels in Chin Hin Street, Fraser Street, Sago Street, Smith Street, Tan Quee Lan Street and Upper Hokien Street.”

Malay Street in the 1910s. The Japanese set up two brothels on Malay Street around 1877. Japanese prostitutes called karayuki-san were favoured by European diplomats and officials. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Malay Street in the 1910s. The Japanese set up two brothels on Malay Street around 1877. Japanese prostitutes called karayuki-san were favoured by European diplomats and officials. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Yan Zhen, a Cantonese teahouse, used to be located at the corner of Trengganu and Smith streets. Smith Street was also a haunt for prostitutes in the early part of the 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Yan Zhen, a Cantonese teahouse, used to be located at the corner of Trengganu and Smith streets. Smith Street was also a haunt for prostitutes in the early part of the 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The hapless women who worked in these brothels – both registered and unregistered – came from all over the archipelago and beyond: many of them were Malays, Sumatrans, Javanese, Chinese and Japanese. And their clients were likewise varied, coming from all the European nations as well as the various Asian communities that resided in the colony. But although illicit sexual unions took place, racial barriers remained: European men were less likely to frequent the brothels where Asian men went to, for fear of disease and pestilence leaping across the racial-ethnic divide.

Though our history books are wont to skip over the lurid details of the past, it cannot be denied that prostitution was an essential part of the colonial enterprise and that it was, in fact, regarded even by some enlightened souls as something both necessary and mundane. Appreciating this fact requires us to remember other aspects of the past which may seem alien to us now, such as the fact that up to the end of the 19th century, the notion that children are human beings endowed with the same rights as adults was likewise regarded as a foreign concept – proof of which could be found in the coal mines of Europe, where children laboured away for hours on end with no regard for their education or welfare, and whose situation invoked scant public protest.

Chinese women chatting along a street in Singapore’s Chinatown area, c. 1938. Allen Goh Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chinese women chatting along a street in Singapore’s Chinatown area, c. 1938. Allen Goh Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In colonies such as Singapore, the issue then was not the rights of the women themselves, but of how to legalise and manage prostitution to keep it within the ambit of the law and the needs of Empire: colonial officials were less concerned about the rights of the women themselves, and more concerned with preventing diseases from migrating from Asian men to European men, with the women regarded as the vectors for the spread of diseases. To that end, Lenore Manderson (1990) has shown how prostitution was seen more as an issue of public health rather than public morality, and how the goal then was of management and control rather than the eradication of prostitution itself. The public sanitation and healthcare programmes that were introduced then were partly the result of this constant fear that certain “Asiatic diseases” would cross the racial threshold and infect the Europeans residing in the colonies.

Among the few groups that were concerned about the plight of the prostitutes were the missionary movements and charity organisations – of various religious persuasions – that sought to rescue these women from their plight and to redeem their moral character. But while such well-meaning organisations sought to rescue the women themselves – some of whom were young girls – few of them were opposed to the colonial enterprise itself, which they nonetheless regarded in a positive light as the harbinger of progress and development to the lesser-developed parts of the world.

The net result of these varied factors working together was the multiple silencing of the voices of Asian women in the colonies of Asia: summarily regarded as “moral unfortunates” or “sullied women”, these unfortunate women were forever cast in the role of the perennial victim (or seductive harlot, in some cases) in need of salvation yet without sufficient moral or intellectual agency of their own. Compounding matters was the fact that most of these prostitutes came from poor families and thus did not have the means to define and shape their own lives, and instead had their identities configured and prescribed for them by the people who wielded control.

Centuries later, the lingering memory of the flesh-dens of Singapore and the other colonies of Southeast Asia would be regurgitated yet again and again, in popular fiction and entertainment, as if the life of a sex worker was the stuff of family entertainment, made all the sweeter by a bland song and dance routine. When the era of legalised prostitution finally came to an end – many brothels in Singapore were cleaned up and closed down in 1927 – it was not the result of an upsurge of human sympathy for the women themselves or a sense of moral righteousness, but rather the result of technological developments that changed the praxis of modern colonialism.

Gentrification and the New Morality of Empire

In the same way that prostitution was one of the negative by-products of racialised colonial-capitalism, the demise of prostitution too was the result of external variable factors that were not necessarily related to each other.

By the turn of the 20th century, much of the world was connected thanks to the communications architecture that had been laid down during the colonial era. The opening of the Suez Canal connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea meant that travel between Europe and Asia was made easier, faster and safer. The days when European seafarers had to cope with the threat of privateers and corsairs were long since over; the seas were now swept clean of pirates thanks to the introduction of the Western gunboat. The transition from the age of sail to the age of steam, and later to fuel-powered vessels, meant that the time taken to travel by sea was shorter, while the volume of cargo and passengers increased considerably with the creation of larger iron-clad vessels. In time, the age of exploration gave way to the age of mass travel and tourism.

By the turn of the 20th century, travel had become much easier and faster, and as the number of European women in the colonies increased, Western men found it less expedient to seek out the company of Asian women. Image reproduced from Liu, G. (1999). Singapore: A Pictorial History 1819–2000. Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]).

By the turn of the 20th century, travel had become much easier and faster, and as the number of European women in the colonies increased, Western men found it less expedient to seek out the company of Asian women. Image reproduced from Liu, G. (1999). Singapore: A Pictorial History 1819–2000. Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]).

In Southeast Asia, these advances in communications had a most profound impact on the composition and appearance of the colonies; one of the most visible changes that took place by the early 20th century was the arrival of more and more European women who had come from Britain, France, Holland and Spain to join their husbands who were working in the East.

As the number of European women in the colonies increased, the colonies themselves became progressively domesticated and gentrified. Prior to the age of mass travel, there were relatively few Western women in the colonial settlements, and those who came were often forced to do so as trailing wives or because of desperate circumstances; few European women made a conscious decision to move to the colonies. Furthermore, a significant number of the women who settled in the East were from the lower classes, and were often relegated to the less respectable levels of colonial society.

But as more and more Western women came to Asia – as a result of faster and safer travel that allowed entire families to be relocated – the number of European men seeking Asian brides declined accordingly. As a result, the character of the hybrid colonies of Southeast Asia began to change and the Dutch, British, French and Spanish colonial functionaries ceased their practice of adopting local customs and dress – in the Dutch East Indies for instance it was common for Dutch colonial officials to wear batik sarong at home, and eat local food cooked by their Indonesian wives.

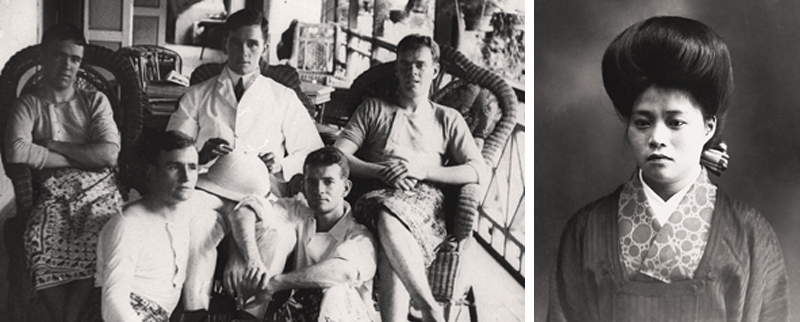

(Left) European bachelors in Singapore took to wearing the sarong at home; some also took on Asian wives or engaged the services of prostitutes, c. 1909. Edward William Newell Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. (Right) Portrait of a Japanese prostitute taken by G. R. Lambert & Company in 1890. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

(Left) European bachelors in Singapore took to wearing the sarong at home; some also took on Asian wives or engaged the services of prostitutes, c. 1909. Edward William Newell Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. (Right) Portrait of a Japanese prostitute taken by G. R. Lambert & Company in 1890. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

In places like Singapore, Georgetown, Batavia, Surabaya and Manila, these societal movements affected other changes as well, leading to the creation of distinct enclaves where Europeans would live among themselves, cut off from the other native Asian communities around them. If having a Eurasian family and Eurasian children was regarded as the norm among the white male colonial functionaries in the 18th century, by the 20th century “going native” was no longer the thing to do. This unfortunately also had serious implications for the thousands of Eurasians in the colonies whose social status was now diminished as a result of the new gentrified social order that was being created around them. No longer were Eurasians seen as a privileged strata of colonial society.

Invariably, the brothels that once dotted the urban landscape of places like Singapore were among the first to be cleaned up. Part and parcel of the gentrification process in the colonies was the sustained effort to erase the traces of vice and inequity that were once stark reminders of the reality of everyday life in the homosocial order of racialised colonialism. Shaped by their new Victorian morals and sensibility, the new European settlers who arrived in Singapore, Georgetown, Batavia and Surabaya were less inclined to mix with the locals and more disposed towards asserting the superiority of their nation, culture and values. What was once deemed exotic and tempting – the oft-repeated metaphor of Asia as the land of pleasure and excess – became regarded as morally repugnant and physically contaminating.

The Need to Remember

Prostitution has been described as the oldest profession in the world, and it has to be stated that colonialism did not invent it or introduce it to Southeast Asia. Long before the arrival of the Western colonial powers and the creation of the colonies that would later evolve to become the nation-states of present-day Southeast Asia, prostitution was already commonplace in the region. But the 19th century witnessed the evolution of a form of racialised colonial-capitalism that introduced distinctions of race and ethnicity that were divisive as they were compartmentalising, and in the course of doing so categorised entire communities, casting them as human capital to be used and appropriated according to the needs of colonialism.

In the course of that process, women were also commodified and their bodies instrumentalised: the Asian women who were brought to the colonies were subsequently used by European and Asian men alike, as this was one of the ways that the machinery of colonialism was kept running over time. Today, controversies linger about the use of “comfort women” in Japanese-occupied territories during World War II, but it has to be remembered that long before the war, women were already being used, albeit in perhaps less coercive ways, by the various colonial regimes across Asia and Africa. Yet comparatively little research has gone into documenting the experiences and histories of such women, lending the mistaken impression that the colonial enterprise of prostitution was as sanitised and prim as colonial propaganda would have us believe.

The eventual demise of prostitution – to be replaced by other systems of social control and domestication – was likewise the result of the development that took place in the colonies themselves, and yet again the ordinary women whose economic function was to service the mechanism of colonialism would later be put to other forms of productive work: as labourers, servants, miners, and in other menial jobs. Yet theirs is a history that deserves to be recorded and documented in detail, for without that our knowledge of Southeast Asia’s past would remain a one-sided story told mainly from the perspective of men.

Most of the women implicated in the trade were of humble origins, and although a few have left behind letters or diaries that can be studied in detail, there is a pressing need to seek sources of information that would shed more light into the grim realities that these women put up with during their lifetimes. For though these women have been largely forgotten and ignored in the official histories of many postcolonial states, theirs is a story of migration, settlement, exploitation and labour that is in every way as compelling and important as the history of male labourers and immigrants, and they too ought to be recognised as being among – the less fortunate – builders of the modern states of Asia today.

Dr Farish A. Noor is Associate Professor and Head of the Doctoral Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He has written widely on subjects related to Southeast Asian history and society, and his latest work is about the colonial construction of the idea of Southeast Asia in 19th-century colonial-capitalist discourse.

REFERENCES

Manderson, L. (1990). Race, colonial mentality and public health in early twentieth century Malaya. In P.J. Rimmer & L.M. Allen (Eds.), The underside of Malaysian history: Pullers, prostitutes, plantation workers. Singapore: Singapore University Press for Malaysia Society of the Asian Studies Association. (Call no.: RSING 305.56209595 UND)

Steinberg, D.J., et al. (Eds.). (1985) In search of Southeast Asia: A modern history. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (Call no.: RSING 959 IN)

Warren, J.F. (1990). Prostitution in Singapore society and the karayuki-san. In P.J. Rimmer & L.M. Allen (Eds.), The underside of Malaysian history: Pullers, prostitutes, plantation workers. Singapore: Singapore University Press for Malaysia Society of the Asian Studies Association. (Call no.: RSING 305.56209595 UND)