Gaston Mèliès and His Lost Films of Singapore

Gaston Méliès may be the first filmmaker to have directed fiction films in Singapore. Unfortunately, none have survived the ravages of time. Raphaël Millet tells you why.

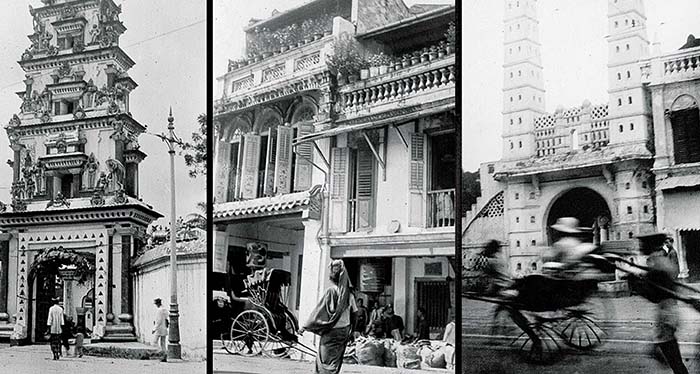

As none of the four films that Gaston Méliès shot in Singapore in January 1913 have survived, photographs such as these taken by members of Méliès’ entourage when they were here at the time likely indicate scenes that may have been captured in the film A Day at Singapore. Pictured here from left to right are Sri Mariamman Temple on South Bridge Road, a shophouse in Chinatown and Masjid Jamae (Chulia Mosque), an Indian-Muslim mosque on South Bridge Road. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

As none of the four films that Gaston Méliès shot in Singapore in January 1913 have survived, photographs such as these taken by members of Méliès’ entourage when they were here at the time likely indicate scenes that may have been captured in the film A Day at Singapore. Pictured here from left to right are Sri Mariamman Temple on South Bridge Road, a shophouse in Chinatown and Masjid Jamae (Chulia Mosque), an Indian-Muslim mosque on South Bridge Road. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.Between 1912 and 1913, while the renowned French filmmaker Georges Méliès was still filming imaginary trips to faraway places in his studio in Montreuil, near Paris, his US-based brother, Gaston Méliès, undertook a 10-month-long trip around Asia Pacific to places such as Polynesia, New Zealand, Australia, Java, Singapore, Cambodia and Japan. During this cinematic adventure, the older and less famous Méliès brother churned out no less than 64 fiction and non-fiction films.

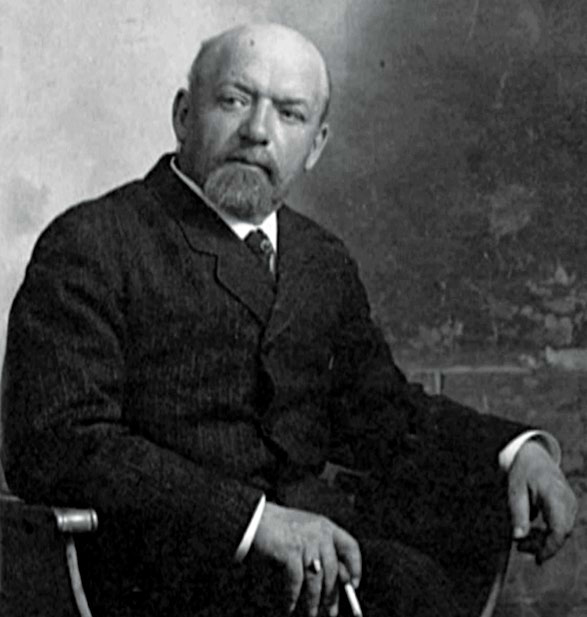

Portrait of Gaston Méliès. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

Portrait of Gaston Méliès. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.Made in Singapore

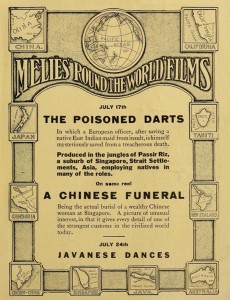

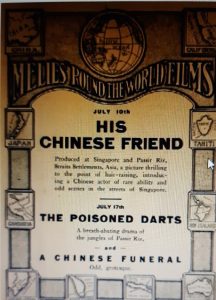

Four of these were filmed in Singapore in January 1913 – which were among the first foreign films shot on location here – and subsequently released in cinemas in the US between 10 July and 4 September 1913. Two of them, The Poisoned Darts and A Chinese Funeral were screened together, “on the same reel” – to use the filmmaking jargon of the period (during the silent film era, the “split reel” comprised two short films of different subjects spliced together into a single reel). This seems to indicate that both films were relatively short; each must have been approximately 150 metres in terms of reel length, and about 5 to 7 minutes in duration. The other two films, His Chinese Friend and A Day at Singapore1 were released separately, which might indicate they were slightly longer productions, what would have been called “one-reelers” (films contained within a standard motion picture reel of film).

Unfortunately, none of the films that Méliès produced in Singapore have survived the passage of time. This is the fate that all silent films of the era share. According to the Film Foundation in the US, an estimated 80 percent of films made before 19292 have been lost through improper storage or fire. As nitrocellulose, the chemical base used for these films is highly flammable, nitrate films have the potential to self-ignite when stored over long periods. It was not unusual for fires to suddenly break out at cinemas when such films being screened in the projection booths would overheat and combust – with patrons running out of the cinemas in panic.

Putting the Pieces Together

In the absence of the physical works, one can only try to piece together what may have taken place during Méliès’ brief but highly creative sojourn in Singapore – one that saw him shoot four films in quick succession. The findings can never be conclusive given the absence of material evidence, but to disregard these early works is tantamount to ignoring a precious part of Singaporean film heritage.

Some details of Méliès’ stay in Singapore can be traced to what remains of the letters he wrote to his son Paul in the US,3 photographs taken during the trip (including those likely taken by his wife Hortense who accompanied him),4 as well as the letters and a photo journal of his cinematographer Hugh McClung.5

Arriving from Batavia on the steamship S.S. Montoro after having toured Java, Méliès disembarked at Singapore on 10 January 1913. Interestingly, he may not have planned to stay long in Singapore, as the weather was reported to have been bad (it had been storming heavily during the last few days of his stay in Java, and the forecast called for rain in Singapore too).6

This was the vessel, the S.S. Montoro, that brought Gaston Méliès and members of his Star Film Company from Batavia, in Java, to Singapore, on 10 January 1913.

This was the vessel, the S.S. Montoro, that brought Gaston Méliès and members of his Star Film Company from Batavia, in Java, to Singapore, on 10 January 1913.McClung, in a letter dated 6 January 1913 sent from Batavia to his sister, wrote of his experience in Singapore: “Just a few lines as we leave tomorrow for Singapore on account of rain, here. And as it is also in Singapore, we will only remain there a day and go on to Bangkok – through Siam and Indo China.”7 But once settled in Singapore, Méliès found it to be “one of the most interesting cities” and rich with filming opportunities. Plans were swiftly changed, and Méliès and his Star Film Company would stay for three full weeks before leaving in early February for his next destination, Cambodia.8

Méliès has been called a “picturemaker”. He was more of a producer than a director, and also a bit of both at the same time, in short, a man who fronted everything himself. This was a time where only the name of the studio mattered: people spoke of “a Gaumont film”, “an Essanay movie”, or “a Vitagraph picture”, the great film studios of the time. Directors, and even less so actors, were rarely credited for their efforts. During both his years in the US and his voyage around Asia Pacific, his productions were known simply as “Méliès movies” – which may have led some to think that they were the works of his better known filmmaker sibling, Georges Méliès.

Gaston Méliès travelled with what the press called “a complete cinematograph outfit”. He was initially accompanied by a director by the name of Bertram Bracken, whom he quickly got rid of as soon as they reached New Zealand. This left Méliès as the de facto director, with the support of George Scott, his “operator for educational pictures” and Hugh McClung, his “dramatic operator”.9

In some of the surviving photographs taken during his trip to Australia and Cambodia, Méliès can be seen seated on a chair, right next to the camera being operated by Scott or McClung, clearly giving them instructions on what to do; Méliès certainly looks like he was playing the part of a film director. This is corroborated by the fact that McClung was only officially promoted to director in April 1913 after the troupe arrived in Japan, where another counterpart, Elgin Lessley, joined them from the US to take over the position of “operator”.10

Part of the travelling posse that arrived in Singapore also comprised a screenwriter by the name of Edmund Mitchell, a Scottish novelist and journalist who had been writing for the daily newspaper The Age in Melbourne, before moving to California where he started penning film scripts for Méliès.11

Although the Singapore press in 1913 seems to have ignored Méliès, they were suitably impressed with Mitchell, who had quite a reputation: “An interesting visitor to Singapore[…] is Mr Edmund Mitchell, who is here in connection with an American Company of cinematograph actors who are engaged in representing eastern plays and legends in their natural settings. Mr. Mitchell has had a long career of travel, having spent many years in India, Australia and America, and he has written a number of interesting books and given lectures in many parts of the world.”12 Known for his stories with “strong plots and vivid local color” and for being “thoroughly familiar with the islands in the South Sea and with Australasia”,13 Mitchell was very likely involved in the screenwriting of the two fiction films – The Poisoned Darts and His Chinese Friend.

Méliès’ entourage also included a few American actors, such as Fanny Midgley14 from Ohio, who began her acting career in Méliès’ Immortal Alamo – shot in Texas in 1911. Did she act in one of Méliès’ made in- Singapore films? There is no evidence to indicate this, as none of the four film synopses contained any major female roles. Besides, the long journey had taken a toll on Midgley; only the comforts of the Adelphi Hotel, where the crew of the Star Film Company stayed, would provide her with some much-deserved respite before she would be ready to face the scorching heat and suffocating humidity of Indochina (their next destination).15 The Adelphi on Coleman Street – torn down in 1973 – was one of the classic hotels of early Singapore, along with the Raffles Hotel and Hotel del’Europe.

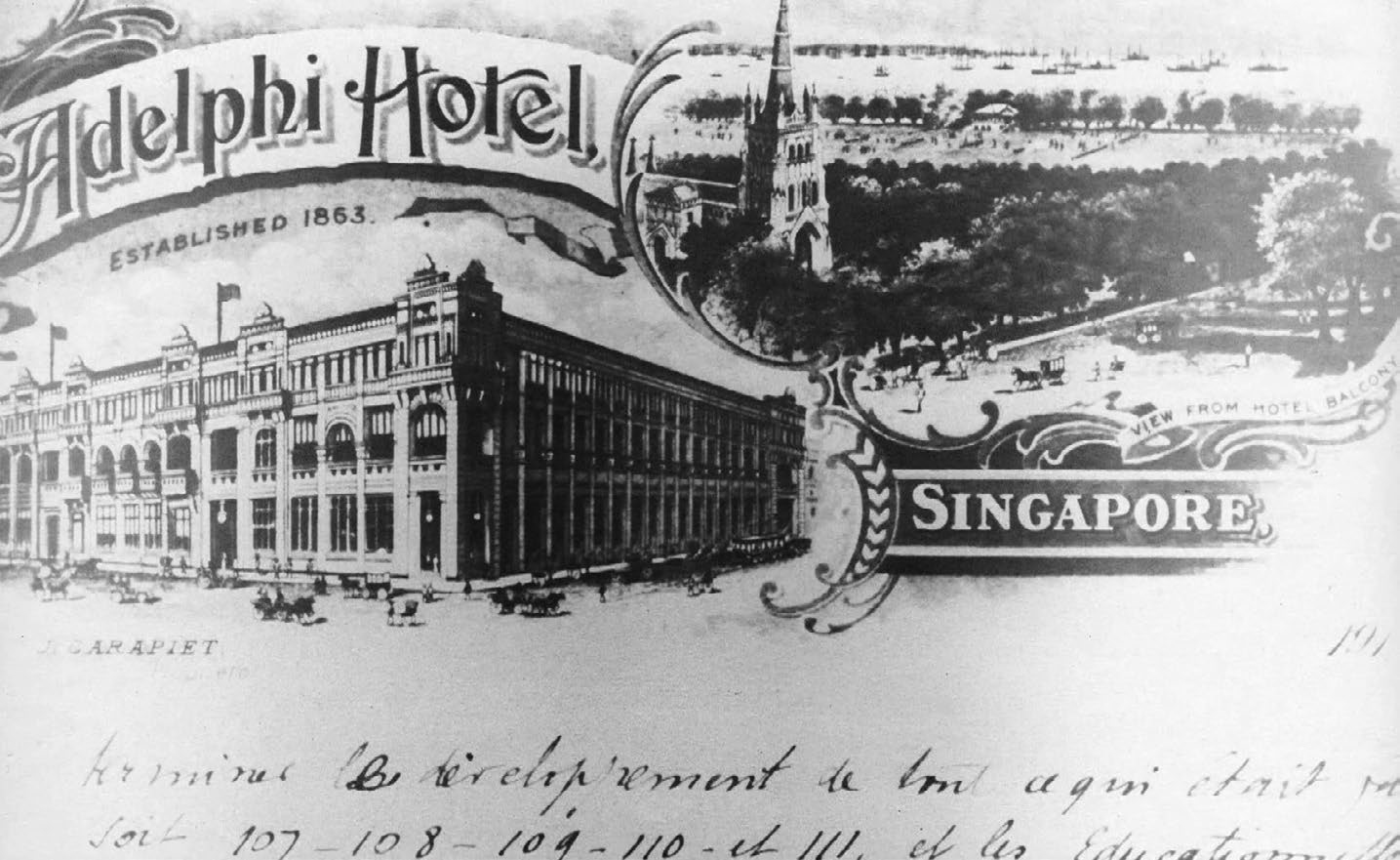

Gaston Méliès and his entourage stayed at the Adelphi Hotel on Coleman Street during their time here in Singapore. This Adelphi Hotel postcard written by Méliès in French is dated 6 February 1913 and was mailed from Cambodia (where Méliès had travelled to after Singapore). The card, addressed to his son Paul in the US, describes Méliès’ stay in Singapore. It also contains instructions on what Paul should do with the films when the reels arrive in the US. All three photos courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

Gaston Méliès and his entourage stayed at the Adelphi Hotel on Coleman Street during their time here in Singapore. This Adelphi Hotel postcard written by Méliès in French is dated 6 February 1913 and was mailed from Cambodia (where Méliès had travelled to after Singapore). The card, addressed to his son Paul in the US, describes Méliès’ stay in Singapore. It also contains instructions on what Paul should do with the films when the reels arrive in the US. All three photos courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.Also on the same trip were Ray Gallagher, a Californian actor who usually played the role of the archetypal villain, and Kansas-born Leo Pierson, who was known for acting as the “juvenile”.16 Both had acted before in some of Méliès’ American productions, and as there were a few Western male parts in The Poisoned Darts and His Chinese Friend, it is reasonable to assume that they took on lead roles in these two films. Indeed, a review of the film His Chinese Friend reports that there are “three leading players, two of them white”.17

Film poster of Gaston Méliès’ The Poisoned Darts and A Chinese Funeral. Both the fiction film and documentary, respectively, were part of the same reel and screened together in the US on 17 July 1913. These were short films, approximately 5 to 7 minutes each in duration. All rights reserved, Moving Picture World, 19 July 1913, Vol. 17, No. 3, p. 379.

Film poster of Gaston Méliès’ The Poisoned Darts and A Chinese Funeral. Both the fiction film and documentary, respectively, were part of the same reel and screened together in the US on 17 July 1913. These were short films, approximately 5 to 7 minutes each in duration. All rights reserved, Moving Picture World, 19 July 1913, Vol. 17, No. 3, p. 379.Movies Before Méliès

Méliès and his team were certainly not the first foreigners to film Singapore. Joseph Rosenthal had done short documentaries on the island for the UK-based Warwick Trading Company as early as 1900.18 So did H. M. Lomas for the Charles Urban Trading Company in 1904, and the French film company Pathé Frères in 1910.19 As for the Vitagraph company, it released its first Singaporean film around the same time as Méliès’, in the summer of 1913.20 However, all of these were strictly non-fiction films, meant to educate and entertain at the same time.

Similarly, two of Méliès four films were documentaries: A Day at Singapore and A Chinese Funeral. Both must have been filmed by George Scott, his “operator for educational pictures”. Whether these were shot under the direction of Méliès is not clear. Having arrived in Singapore a few days ahead of Méliès (who had stayed behind in Surabaya with the rest of his crew to film Java and its “monuments of bygone splendor”21), Scott would have had time on his own to film at least some of the scenes in A Day at Singapore.

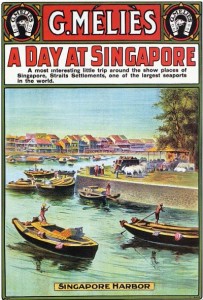

A Day at Singapore, a short documentary film shot in Singapore in January 1913, by Frenchman Gaston Méliès has sometimes been incorrectly attributed to his younger brother Georges as they share names that begin with the letter “G”. In reality, the more famous filmmaker Georges Méliès (who worked at his studio in a Parisian suburb) had never set foot in Singapore. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

A Day at Singapore, a short documentary film shot in Singapore in January 1913, by Frenchman Gaston Méliès has sometimes been incorrectly attributed to his younger brother Georges as they share names that begin with the letter “G”. In reality, the more famous filmmaker Georges Méliès (who worked at his studio in a Parisian suburb) had never set foot in Singapore. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.The film was advertised as “a most interesting trip around the show places of Singapore, Straits Settlements, one of the largest seaports in the world”.22 Since there is no surviving reel, it is impossible to offer a direct assessment of the work. The only reference is a review published in September 1913 that said “perhaps too many feet were given to these scenes in Singapore, on account of the dark photography. […] The offering includes street and water scenes with some buildings. It has good educational value”.23

As for A Chinese Funeral, it was apparently an “actual burial of a wealthy Chinese woman”, advertised as “one of the oddest sights that can be beheld by the traveler in the Far East. The procession is led by a gong band creating terrific noises to scare away the evil spirits. Giant grotesque figures are employed for the same purpose. All the friends of the deceased parade to the grave where, while the casket is being lowered and covered with cement, they partake of a meal furnished by the deceased’s relatives. It is the Chinese custom to feast and be happy as a fitting culmination to the long days of prayer and vigil”.24 The documentary was reviewed as a “remarkably instructive picture. […] It is very well photographed and there is an astonishing amount of matter on it. A very good offering”.25

Another photo taken by a member of the Gaston Méliès’ Star Film Company. Likely shot in Chinatown and depicting an elaborate Chinese funeral procession, a similar scene could have appeared in the documentary A Chinese Funeral.

Another photo taken by a member of the Gaston Méliès’ Star Film Company. Likely shot in Chinatown and depicting an elaborate Chinese funeral procession, a similar scene could have appeared in the documentary A Chinese Funeral.The First Singapore-Shot Fiction Films

But what distinguishes Méliès and makes him a true pioneer is that he produced what are possibly the first two made-in-Singapore fiction films. Even more outstanding is that he hired local people (unfortunately referred to as “natives”) to act in his films, not just as extras in the background, but as real actors. This was unusual for the time as the practice was to use poorly made-up Caucasian actors to play non-Western parts of Africans, Indians and Asians.

Right from the start, Méliès was intent on having locals act in his films, declaring to the press: “Our actors will take the leading roles and will be aided by the natives of the country through which we are passing.”26 As soon as Méliès reached Polynesia, he hired some Tahitians. Finding them as good or even better than some of his Western actors,he quickly decided to give them lead parts in his films. It worked out so well that he did the same in New Zealand with the Maoris, in Australia with the Aborigines, and in Java with the Javanese, moving away from the racist practice of hiring a white person to act as a black-face or yellow-face – using make-up to look African or Oriental.27 Yet, hiring local “players” (as they were called back then) was not just an ethical choice or an idealistic move on the part of Méliès: it was probably a hard-nosed business decision aimed at keeping his costs low while, at the same time, increasing the marketability of his own productions and giving him an edge over his competitors.

With this mindset, Méliès immediately set out to work with locals when he arrived in Singapore on 10 January 1913. When The Poisoned Darts was released six months later on 17 July 1913, the advertisement in the Moving Picture World magazine dated 19 July proudly proclaimed that it was “produced in the jungles of Passir Riz [Pasir Ris], a suburb of Singapore, Strait Settlements, Asia, employing natives in many of the roles.”28 The actors were most likely inhabitants of Malay villages in the Pasir Ris area, as the only surviving footage of this film on the facing page seems to corroborate. The film was reviewed as being “fresh and of great interest, because it has been made truly convincing”, wrote the commentator adding that: “The photography of the jungle and its people is clear and often beautiful.”29

Similarly, Méliès obviously found a local actor to play Wing, the lead Chinese part in His Chinese Friend. An advertisement published in the 12 July 1913 issue of Moving Picture World hailed the film as “a picture thrilling to the point of hair-raising, introducing a Chinese actor of rare ability and old scenes in the streets of Singapore”.30 Another review in the 26 July 1913 edition of Moving Picture World stated that “it is a good picture” for “it has a Chinese player who is cheery-faced and who acts very creditably”.31 Unfortunately we know nothing more about this Chinese actor, much less his name.

Film poster of His Chinese Friend, The Poisoned Darts and A Chinese Funeral. Both His Chinese Friend and A Day at Singapore were longer standalone films that were released separately. The fiction film The Poisoned Darts and the documentary A Chinese Funeral were shorter films that were part of the same reel and screened together. All rights reserved, Moving Picture World, 12 July 1913, Vol 17, No. 2, p. 271.

Film poster of His Chinese Friend, The Poisoned Darts and A Chinese Funeral. Both His Chinese Friend and A Day at Singapore were longer standalone films that were released separately. The fiction film The Poisoned Darts and the documentary A Chinese Funeral were shorter films that were part of the same reel and screened together. All rights reserved, Moving Picture World, 12 July 1913, Vol 17, No. 2, p. 271.Méliès’ own approach to film raises many questions of identity, otherness and representation, giving us a better understanding of his place in early cinema and in Singapore’s film history. At the time of writing, there is no surviving print of Méliès’ made-in-Singapore films. These are what film historians and archivists call “lost films”, the same fate that befell most of the other works he filmed during his cinematic journey across Asia-Pacific in 1913. Out of the 64 films that Méliès shot during his eventful trip, only five survived, some of which are literally in fragments today. And out of four films made in Singapore, none exist. But lost films are not always lost forever, as a print can surface, sometimes in the most unexpected of places. There is hope yet for what might seem like an obscure French filmmaker who was also one of the pioneers of Singapore’s film history.

MÉLIÉS’ FICTION MELODRAMAS

The Poisoned Darts 32

A shipwrecked crew, comprising an officer and several men, find themselves on a remote island in the East Indies. After consuming the scant stores saved from the ship, they venture inland into the forest. One of the crew, having seized a native girl one evening, is upset when the officer releases the girl and sends her on her way. Unhappy by this turn of events, the men lay hold of the officer the next morning and bind him to a tree. They resolve to kill him, and lots are drawn to determine who shall commit the heinous deed. One man is chosen, and is in the act of raising the officer’s pistol to shoot him when a poisoned dart from the direction of the jungle ends the would-be perpetrator’s life. The officer’s bonds are at the same time severed by a knife, and a dusky silhouette quickly disappears into the bushes behind the tree, unseen by the captive officer.

Wondering how he became untied, but thankful to be free, the officer follows his his men and once more takes command. The survivors struggle through the forest, but one by one, as they try and man-handle the officer, the attackers fall victims to poisoned darts mysteriously shot from the jungle. At last the officer is alone, and, utterly wearied, falls asleep under a tree. On awakening he finds fruits, cakes and water by his side. Then he realises that because he saved the girl, the unseen natives have been paying the good deed back. Eventually the natives appear, invite him to their village, and nurse him through a fever. News is brought of a passing ship, and the castaway is carried to the beach by his newfound native friends, and eventually rescued by the passing vessel.

This still from Gaston Méliès’ fiction film The Poisoned Darts, published in the 19 July 1913 edition of Moving Picture World – one of the earliest periodicals on the motion film industry – is the only known scene taken from the film that was shot on location in Singapore. Filmed at “Passir Riz” (Pasir Ris), the non-Caucasian actors in the scene are likely Malay “natives” living in the kampongs in the area. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

This still from Gaston Méliès’ fiction film The Poisoned Darts, published in the 19 July 1913 edition of Moving Picture World – one of the earliest periodicals on the motion film industry – is the only known scene taken from the film that was shot on location in Singapore. Filmed at “Passir Riz” (Pasir Ris), the non-Caucasian actors in the scene are likely Malay “natives” living in the kampongs in the area. Courtesy of “Gaston Méliès and his Wandering Star Film Company” © Nocturnes Productions, 2015.

His Chinese Friend 33

Playing on the streets of Singapore with Wing, his little Chinese friend, three-year- old Charlie Foster, an American lad, is suddenly kidnapped. It does not take long for Wing to grasp the severity of the situation; he promptly informs the police and saves his playmate’s life.

Fast forward 25 years and the two are still firm friends. Foster, now married, is a speculator of rubber. However, as a result of a slump in the stock market, financial ruin stares him in the face. Once more Wing comes to the rescue of his friend, using his savings and raising money on his personal credit to tide Foster over until another boom in rubber makes him wealthy.Some 10 years pass and Wing is a high official, but secretly a leader in the Chinese revolution. The authorities become aware of his double dealing and issue a warrant offering a reward for his arrest. Foster learns of this and quickly hurries in his car to Wing’s palatial home, and spirits him away to his office. But they are followed and Wing is fired at. He drops to the ground, apparently lifeless.

News spreads that Wing is dead and a great funeral is held. But Wing is very much alive, and Foster, in a bid to save his loyal friend’s life, nails him shut into a box marked for shipment to Europe. Once the box is hoisted onto the steamer, it is prised open and Wing emerges. The two friends part, swearing eternal devotion to each other.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

NOTES

-

In Vol. 2 Issue 01 (April 2015) of BiblioAsia, in the article Tan, B. (2015, April-June). From Tents to Picture Palaces: Early Singapore Cinema, 11 (2). BiblioAsia. Retrieved from BiblioaAsia website, A Day at Singapore was incorrectly attributed to Georges Méliès when it should be Gaston Méliès. The article cites the online film source IMDb, which mentions Georges Méliès in the film credits. Promotional posters of the film that contain the words G. Méliès is a likely reason why this confusion may have arisen. Georges Méliès rarely filmed outside the confines of his studio in the Parisian suburbs and there is no record of him ever travelling to Singapore. ↩

-

The Film Foundation. (2016). Preservation. Retrieved from The Film Foundation website. ↩

-

Méliès, G. (1988). Le Voyage autour du monde de la G. Méliès Manufacturing Company (juillet 1912 – mai 1913) (143pp). Paris: Association les Amis de Georges Méliès. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Private collections of Jacques Malthête, great-nephew of Gaston Méliès, and David Pfluger, collector of all things related to Georges and Gaston Méliès. ↩

-

Unpublished letters and photo diary. Private collection of David Pfluger. ↩

-

Méliès, 1988, pp. 83–87. ↩

-

Unpublished. Private collection of David Pfluger. ↩

-

Méliès, 1988, pp. 83–87. ↩

-

Tired of cowboys. (1912, August 20). Marlborough Express, XLVI (197), 2. Retrieved from Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand website. ↩

-

Elgin Lessley’s portrait as part of “Who’s Who in Long Pants”. (1927, January 22). Moving Picture World, p. 265. ↩

-

Marlborough Express, 20 Aug 1912, p. 2. ↩

-

Personal pars. (1913, January 14). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Judson, H.C. (1912, August 24). Méliès Globe Trotters reach Tahiti islands. Moving Picture World, 13 (8), 774. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Marlborough Express, 20 Aug 1912, p. 2. ↩

-

Méliès, 1988, pp. 83–87. ↩

-

Marlborough Express, 20 Aug 1912, p. 2. ↩

-

His Chinese Friend. (1913, July 26). Moving Picture World, 17 (4), 428. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Circular Panorama of Singapore and Landing Stage,Coolie Boys Diving for Coins and Panorama of Singapore Sea Front (pp. 311, 317). (1997). In Barnes J, The beginnings of the cinema in England, 1894–1901 (Vol.5, 1900). Indiana: University of Exeter Press. ↩

-

These include A Coco-nut Tree Plantation in Singapore (Reference #1910PDOC 00149) and Singapore (Reference #1910-2), available in the Gaumont Pathé Archives. ↩

-

Quaint Singapore. (1913, August 23). Moving Picture World, 17 (8), 868. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

The Méliès trip around the world. (1912, November 23). Motography, 8 (11), 398. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Advertisement: A Day at Singapore. (1913, September 6). Moving Picture World, 17 (10), 1127. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

A Day at Singapore. (1913, September 4). Moving Picture World, 17 (12), 1283. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Méliès: A Chinese Funeral. (1913, July 12). Moving Picture World, 17 (2), 234. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Comments on the films: A Chinese Funeral. (1913, August 2). Moving Picture World, 17 (5), 535. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Marlborough Express, 20 Aug 1912, p. 2. ↩

-

Méliès, 1988, pp. 21–80. ↩

-

Advertisement: Méliès “Round the World” films. (1913, July 19). Moving Picture World, 17 (3), 379. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Comments on the films: The Poisoned Darts. (1913, July 17). Moving Picture World, 17 (5), 535. ↩

-

Advertisement: Méliès “Round the World” films. (1913, July 12). Moving Picture World, 17 (2), 271. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Comments on the films: His Chinese Friend. (1913, July 26). Moving Picture World, 17 (4), 428. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Méliès: The Poisoned Darts. (1913, July 12). Moving Picture World, 17 (2), 234. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Méliès: His Chinese Friend. (1913, July 5). Moving Picture World, 17 (1), 78. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩