One Small Voice: The Monodrama in Singapore Theatre

Emily of Emerald Hill is one of Singapore’s most iconic single-person plays. Corrie Tan tells you more about the history of the monodrama on the Singapore stage.

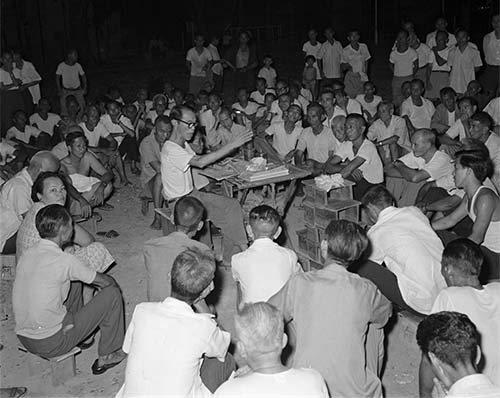

A Chinese street storyteller (circa 1950) regales his enraptured audience with stories from Chinese classics, legends and folktales. From the Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚慰收集). All rights reserved, Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board Singapore 2007.

A Chinese street storyteller (circa 1950) regales his enraptured audience with stories from Chinese classics, legends and folktales. From the Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚慰收集). All rights reserved, Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board Singapore 2007.An unnamed man stepped onto a bare stage in 1985. He was dressed in a plain white shirt and black pants, the colours of mourning – but also the Singaporean workingman’s uniform. Anonymous, blending in, like everyone else. His attire echoed the type of clothing that itinerant Chinese storytellers wore during the colonial period and into the 1960s as they regaled audiences with tales of martial arts and straying deities.1

But this man was not a storyteller, even though he did tell a story that would go on to captivate Singaporean theatre audiences and leave such a mark on local theatre history that the play has become, perhaps, one of the country’s most cited productions today. It was Kuo Pao Kun’s cutting allegory The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, where a frustrated, man-in-the-street narrator grapples with a bizarre bureaucracy and society’s traps of conformity at his grandfather’s funeral because the deceased’s coffin is, as the title puts it, just too big for the hole.

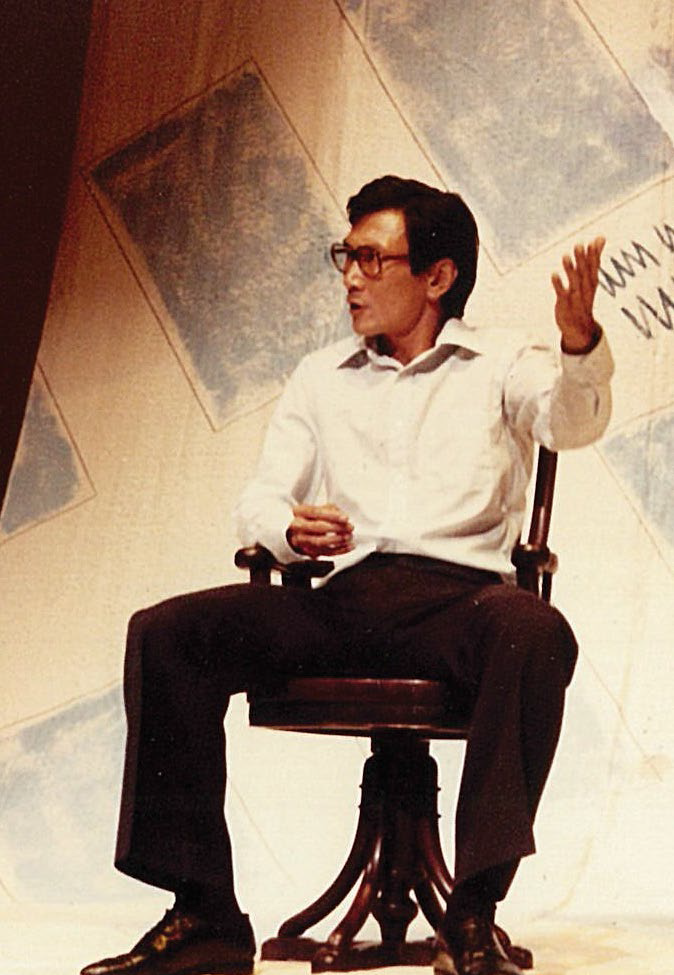

Actors Lim Kay Tong and Zou Wenxue were the original leads, with Lim performing in English and Zou in Mandarin. The late Kuo, a charismatic dramatist and director who shaped much of Singapore’s early contemporary theatre, used rehearsal methods that, to Lim, were quite bewildering. The veteran actor discussed these preparations in a 2014 interview with The Straits Times:

“For me, that was panic stations. I had never done a long monologue. In drama school, we had to prepare monologues based on a Shakespearean character. Nothing like this, which was 30 to 35 minutes long. And he [Kuo] spent at least a couple of weeks just talking to me. I was worried. Because I thought, when is he going to get down to it?”

Lim Kay Tong performs in the 1985 English Production of Kuo Pao Kun’s The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, where a frustrated, man-in the-street narrator grapples with a bizarre bureaucracy and society’s traps of conformity at his grandfather’s funeral. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.

Lim Kay Tong performs in the 1985 English Production of Kuo Pao Kun’s The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, where a frustrated, man-in the-street narrator grapples with a bizarre bureaucracy and society’s traps of conformity at his grandfather’s funeral. Courtesy of The Theatre Practice Ltd.One of the few directions Lim recalls Kuo giving him was to stand up at certain points in the play:

“He seemed to focus on whenever the script came back to the coffin. Those were the moments of focus. The rest of the time he just said, ‘Tell the story’. That was all.”2

The simplicity of Kuo’s direction proved powerful. To stand, to sit, to gesture, to speak meaning into a small, empty space – one might call to mind what British theatre director and luminary Peter Brook wrote in his seminal 1968 text, The Empty Space:

“I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across an empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.”3

But one might also look at Singapore’s street storytellers of the 1950s and 60s, the likes of Lee Dai Sor and Ong Toh who popularised what was known as jiang gu (讲古; “telling old stories” in Chinese), and who understood not just the simplicity or the individuality of the theatre, but the possibilities of communality. Theatre is, after all, also a communal experience, where a single character’s journey is magnified through the sympathies and empathies of the audience.

The storytelling tradition is still strong in Singapore today, with various groups and festivals dedicated to the art of telling a story, but it is hard not to see the connections between these traditional forms of storytelling and its theatrical cousin, the monodrama,4 which has been a key dramatic form in the development of contemporary theatre in Singapore. The monodrama replicates the spirit of that environment, with its stripped-down set and props, and asserts the magic of performance: as one person can play a multitude of characters, so too can one small country contain legions of stories.

The Beginning of the Monodrama

Immediately preceding the seminal Coffin was Stella Kon’s 1984 classic, Emily of Emerald Hill. Kon had written the play in 1981 but could find no one to direct or perform it after submitting it for the 1983 Singapore National Playwriting Competition. She said in an interview with the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore in 2002:

“When it won the award, we couldn’t get any Singapore director to produce it because, well, this one-woman-play format, it was very unseen in Singapore. You know that I didn’t invent the form, I’d seen one-person plays abroad, but it wasn’t known here. So the local directors, they asked how can one person maintain the attention of the audience for that length of time.”5

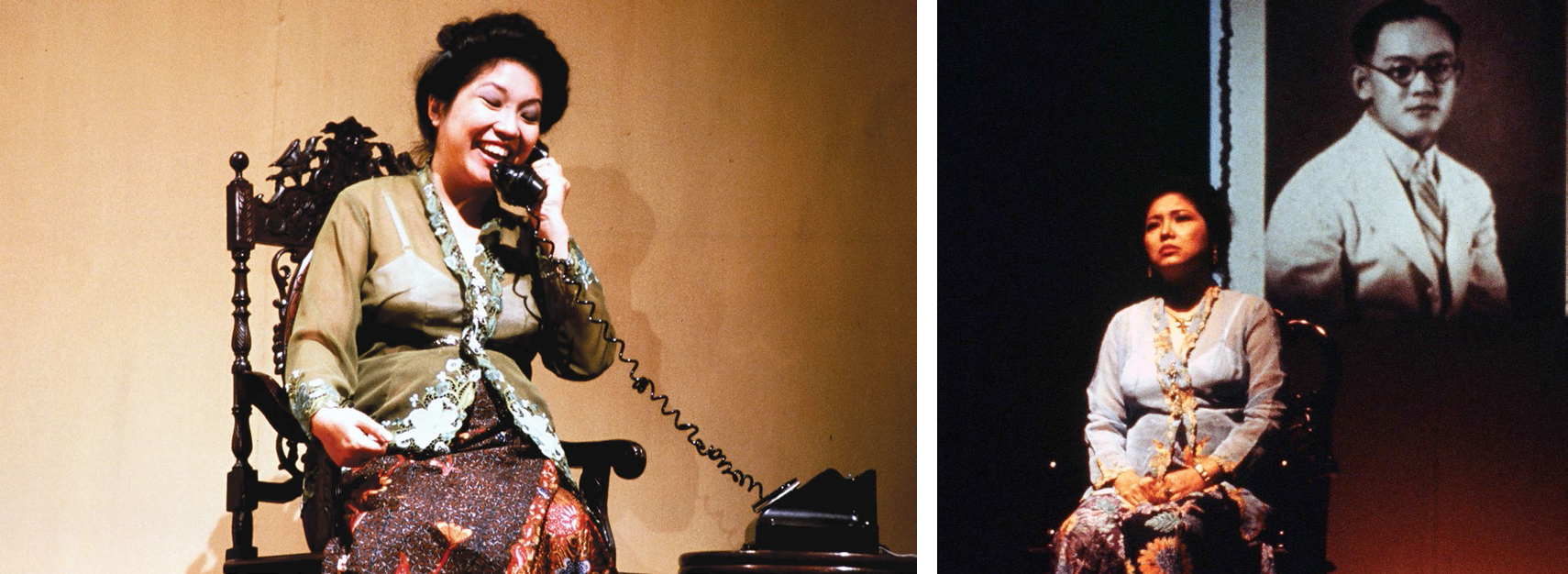

It was not until Malaysian director Chin San Sooi and playwright-actress Leow Puay Tin took the plunge in 1984 – staging the monodrama in remote Seremban – that Emily emerged into the spotlight. The monodrama was produced in Singapore a year later, starring stage actress Margaret Chan and directed by university lecturer Max Le Blond.

Stella Kon’s Emily of Emerald Hill (1984) is one of Singapore’s most iconic single-person plays. The monodrama was first produced in Singapore in 1985, starring stage actress Margaret Chan and directed by university lecturer Max Le Blond. Courtesy of Dr Margaret Chan.

Stella Kon’s Emily of Emerald Hill (1984) is one of Singapore’s most iconic single-person plays. The monodrama was first produced in Singapore in 1985, starring stage actress Margaret Chan and directed by university lecturer Max Le Blond. Courtesy of Dr Margaret Chan.The success of Emily in terms of its one-woman format and warm audience reception marked a high point of a fertile period in Singaporean theatre in the 1980s;6 the Ministry of Community Development, which organised the 1985 Drama Festival, wanted to repeat Emily’s success by publicising the National Playwriting Competition, which Kon had won in 1983 with Emily. A deputy director at the ministry was reported as saying: “Emily proves that there is a Singaporean audience appreciative of Singaporean works.”7 The play was also invited to the UK’s Commonwealth Arts Festival and the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, both in 1986.

But until that point, the monologue and monodrama had made few ripples in Singaporean theatre. Chinese-language theatre in Singapore in the early 1900s comprised mostly ensemble productions with a strong moralistic or didactic streak. A 1914 Chinese-language production of The Heroine (巾帼须眉), for instance, had strong feminist leanings, “depicting the importance of women’s education and social orality”. It featured the female principal of a girls’ school who goes through great familial ordeals but eventually saves the day. In 1918, a trilogy of plays staged in Singapore as part of a fundraiser to aid victims of floods in Guangdong, China, dealt with various hot-button issues of the day, including one that critiqued arranged marriages, another that spelled the downfall of the rich and heartless, and one where a promiscuous man ends up bankrupt and in disrepute.8

The monologue in Singapore’s English language theatre was, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, often presented as part of a revue line-up or an evening of light entertainment, always by expatriate groups or individuals passing through the region. They were usually staged at the Victoria Theatre, formerly known as the Town Hall, as early as 1892, when a W. M. Freear, who was “spoken of very flatteringly in all places where he has shown his entertaining talent”, presented his “monologue entertainment” titled Frivolity – something more of a standup comedy bit from a stage entertainer than a monodrama.9 A subsequent review in The Straits Times affirmed his skill, that “From the commencement to the finish, Mr. Freear ably succeeded in keeping his audience in excellent humour evidenced by the continual round [sic] of laughter”.10 Subsequent “monologue artistes” included Harry Quinningborough, part of a line-up by the London Musical Comedy Company in 1911;11 Harry Russon from the Humphrey Bishop Company in 1916;12 and Percy Baverstock with a “heartily encored” Tale of a Dog from the Leyland Hodgson Revue Company in 1920.13

Monologues continued to be staged throughout the 1930s, prior to World War II, but gradually drifted out of popularity until the 1970s, when English actor Brian Barnes performed two one-man plays at the Regional English Language Centre in 1972 that also demanded audience participation. Violet Oon, writing for the New Nation newspaper, described it as “a new form of theatre” for the Singaporean audience – “one couldn’t quite tell when Barnes was playing himself, the actor on stage or the actor acting the actor.”14

The Individual versus Society

The reputation of the monodrama in Singapore was cemented only by the dramatic peaks of The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole and Emily of Emerald Hill, staged almost back to back in Singapore in 1985. One represented the frustrations of an everyman tired of Singapore’s bureaucratic system, and the other, the universal story of motherhood and what it meant to be a woman in a man’s world.

It was part of a tide of theatre that decisively sought to distinguish itself as Singaporean or Malayan theatre, a break from the colonial tradition, including the amateur theatre societies often set up by expatriates that featured imported work from other English-speaking countries or from China. Other playwrights and writers working to establish an indigenous identity in the arts included Goh Poh Seng, Lim Chor Pee and Robert Yeo, who were experimenting with the flavour of the Singaporean play – the lexicon, the language, and the country’s social and political preoccupations from the 1960s to the 1980s. In 1960, the former Nanyang University’s Drama Research Society presented three plays by Singaporean and Malayan playwrights in response to Singapore’s self-governance in 1959.15 There was a desire for work that resonated with a local audience – a locality and culture that set itself apart from the region as Singapore took steps towards nationhood.

Perhaps another reason why the monodrama occupies such prime estate in Singapore’s theatre history is because of the David and Goliath imagery it evokes – of one person facing an oppressive, chaotic world and trying to make sense of it, or standing up against what they believe is wrong and should be righted.

Prominent theatre group The Necessary Stage was one of the companies that was founded during the burgeoning growth of indigenous theatre in the late 1980s, and one of their earliest productions was the monodrama Lanterns Never Go Out (1989) by the company’s founder and artistic director, Alvin Tan, and resident playwright, Haresh Sharma. Their inspiration was actress Loh Kah Wei, with whom they did extensive interviews, and who eventually starred in the play.

In his 2004 essay analysing The Necessary Stage’s aesthetic strategies in the late 1980s, writer Tan Chong Kee notes:

“The artists observed their immediate surroundings and asked how an individual could stand up to normative social strictures. In Lanterns Never Go Out (1989), the central character, Kah Wei, is torn between submitting to social expectations that is moulding her life into a fixed progression from school, university, work, marriage, babies to grandchildren; and her own desire for something else, symbolised by a goldfish-shaped lantern. Even while Kah Wei struggles to resist hypocritical and conformist social norms, she is carried along by its current. Her struggle is between doing what she wants and doing what others want of her.”16

This struggle between what is desired and what is expected found the perfect conduit in the monodrama – one could draw a line from the acerbic elderly Peranakan bibik (auntie) of Emily of Emerald Hill to the beleaguered Kah Wei in Lanterns and to the recent monodrama, Best of (2013), written for The Necessary Stage’s 25th anniversary, where a confiding, charming young Malay-Muslim woman wants a divorce from her husband but cannot get one. Kon and Sharma’s three monodramas all cast their eye on strong women hemmed in by society’s dictates. For Alvin Tan, the form of delivery was key. In his preface to Best of, published in 2014, Tan wrote that they “had wanted a monologue where the virtuosity of the performer is not measured by the number of characters she is able to perform with aplomb, but rather to maintain a direct conversation flow, engaging the audience with an aggregate of minute vignettes and quick exchanges between characters”.17

Best Of, which was performed by award-winning actress Siti Khalijah Zainal, bore thematic similarities to provocative Tamil writer Elangovan’s fiery Talaq (1998), a 90-minute one-woman play mired in a censorship tug-of-war between the artistes involved and the Public Entertainment Licensing Unit (PELU) that made headlines over the course of several weeks in 2000. The show’s second run in Malay and English was ultimately not granted a performance licence, as noted in an Asiaweek article:

Best Of (2013), written by Haresh Sharma and performed by award-winning actress Siti Khalijah Zainal, is about a confident, charming young Malay-Muslim woman who wants a divorce from her husband but cannot get one. Photo by Alan Lim. Courtesy of The Necessary Stage.

Best Of (2013), written by Haresh Sharma and performed by award-winning actress Siti Khalijah Zainal, is about a confident, charming young Malay-Muslim woman who wants a divorce from her husband but cannot get one. Photo by Alan Lim. Courtesy of The Necessary Stage.“Talaq is really the story of [actress Nargis] Banu’s broken marriage – and that of 11 other Indian Muslim women like herself. Talaq, which loosely translates as “divorce”, gives voice to the abuse and misery they have endured in silence. Though there have been just three shows so far [all to packed houses], the Tamil-language drama has enraged sectors of the Indian Muslim community in Singapore.”18

Actress Nargis Banu, who played the lead, became the target of hate mail and death threats as the controversy broke, as did Elangovan. Many objected to what they felt was the inaccurate and unfavourable depiction of Islamic law as it applies to marriage. The play was first staged in Tamil in December 1998 and then in February the following year with the go-ahead from both PELU and the National Arts Council. While Talaq “provoked strong protests from Muslim Indians, with religious groups calling for it to be banned”, it was also “lauded by press reviews for its raw power and intensity, even reducing many in the audience to tears”.19

Once again, the monodrama format heightened both Banu’s aloneness – but also her courage. Here was a woman who refused to be silenced despite knowing the enormity and difficulty of telling her story, that “violence and rape, already sensitive subjects, would be even more controversial in the context of a Muslim marriage”.20 But both Banu and Elangovan were heartened by the women who approached them, in private, to express their support for the play.

Several other Singaporean monodramas have had strong feminist themes that put leading ladies and the challenges of womanhood in the spotlight. There is Haresh Sharma’s Rosnah (1995), which looks at a young Malay-Muslim woman from Singapore who travels to London to study, where she encounters culture shock and values that are discordant with her own upbringing; and Zizi Azah’s How Did the Cat Get So Fat (2006), in which a nine-year- old girl goes on a fantastical journey where she meets Singaporeans from all walks of life and deals with race relations, political rhetoric and class issues.

Theatre practitioner Li Xie’s one-woman Mandarin play, The VaginaLogue (阴道独白), an examination of the symbol of the vagina and its place in society – in the spirit of Eve Ensler’s groundbreaking The Vagina Monologues (1996) – was also staged in 2000 to critical acclaim. Former theatre critic Clarissa Oon wrote in The Straits Times that the “wonderfully layered” show had “a real identification with all those nameless women, and occasionally, a conceptual distance for you to mull on the issues… It was that rare thing: a journey into the private reaches of the self, without a shred of indulgence”.21

Making the Private, Public; the Personal, Universal

By making what is private public, a well-crafted monodrama can move beyond the confessional – the “indulgence” that Oon implies – and into the realm of the universal. The personal story becomes a shared one, with the actor or actress speaking on behalf of the marginalised and the voiceless, or confronting issues that have been swept under the rug and giving them a public airing, garnering a much wider resonance.

Writer-director Oliver Chong based his critically-acclaimed monodrama, Roots (2012), on a story highly specific to his own family. After a cryptic conversation with his grandmother about a branch of his family tree, Chong decides to return to his ancestral hometown in China to trace what seems to be a family secret. Blending humour, pathos and a virtuosic array of characters, Chong’s one-man act struck a chord with its audience – an audience of Singaporeans largely descended from immigrants who arrived here several generations ago.

Oliver Chong in Roots (2012), a monodrama that he also wrote and directed. Blending humour, pathos and a virtuosic array of characters, Chong’s one-man act struck a chord with its audience – an audience of Singaporeans largely descended from immigrants who arrived here several generations ago. Photo by Tuckys Photography. Courtesy of The Finger Players.

Oliver Chong in Roots (2012), a monodrama that he also wrote and directed. Blending humour, pathos and a virtuosic array of characters, Chong’s one-man act struck a chord with its audience – an audience of Singaporeans largely descended from immigrants who arrived here several generations ago. Photo by Tuckys Photography. Courtesy of The Finger Players.As Chong goes in search of his roots, a netizen from Hong Kong writes to him in traditional Chinese script, oozing condescension: “My surname is also Chong. But my ‘Chong’ is different from yours. Yours has been castrated. So why bother to find any roots? You don’t have roots any more.”22

There is a strong echo of the words of Kuo Pao Kun in his play Descendants of the Eunuch Admiral (1995), not specified as a monodrama but completely written in prose, without any demarcations of various characters or different voices. At first glance, Descendants looks at the life of Admiral Cheng Ho (郑和; Zheng He), who was sent by the Ming emperor to explore the world in the 15th century. There are scenes detailing the strange and great wonders he sees, the painful act of losing his manhood as a eunuch in his majesty’s court, and his great loneliness as he traverses the oceans. But the lyrical piece is also a meditation on rootlessness, displacement and being a “cultural orphan”. Kuo had lamented that Singaporeans were cultural orphans, the “children” of the castrated Cheng Ho, separated from our cultural homelands, yet unable to identify with them as our cultural homes – and cursed to wander and search at the margins.

This anxiety over ancestry is perhaps a symptom of larger issues of memory and remembrance that weigh heavily on the Singaporean conscience. While Roots is the story of one man unravelling his family’s past, it also reflects a larger narrative – that of an immigrant nation, whose ancestors left their families to forge new ones, as this author pointed out in a Straits Times article:

“The power of Chong’s intimate, compelling Roots lies both in that anxiety over ancestry, but also the ability to lay it to rest – to embrace it as part of our history and soldier through it to find an identity of our own.”23

These preoccupations also come to light in playwright Huzir Sulaiman’s Occupation (2002), a monodrama revolving around his own grandmother, Mrs Mohamed Siraj, and her real-life experiences growing up in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation. The monodrama, first performed by Claire Wong in 2002 and Jo Kukathas in 2012, was a popular and critical success. As Mrs Siraj responds to questions and prompts from an oral history collector, the audience becomes aware of a larger tapestry at work, as writer and editor Kathy Rowland states in the preface to Huzir’s collection of plays:

“The conceit of the oral history collector archiving Mrs Siraj’s wartime memories gives motion to the action, allowing the narrative to move between past and present in a fluid way. Indeed, this confluence of past and present is essential, for the play looks at how contemporary needs shape the way the past is remembered.”24

Jo Kukathas performs in the 2012 production of Huzir Sulaiman’s Occupation (2002). The monodrama revolves around Huzir’s grandmother, Mrs Mohamed Siraj, and her real-life experiences growing up in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation. Photo by Tan Ngiap Heng. Courtesy of Checkpoint Theatre.

Jo Kukathas performs in the 2012 production of Huzir Sulaiman’s Occupation (2002). The monodrama revolves around Huzir’s grandmother, Mrs Mohamed Siraj, and her real-life experiences growing up in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation. Photo by Tan Ngiap Heng. Courtesy of Checkpoint Theatre.One woman’s recollection then becomes one country’s meditation on memory. It reframes the narrative of World War II and how the generations since then have been conditioned to reflect on that period of time. The questions that Sarah, the oral history collector, poses to Mrs Siraj, are likewise recontextualised:

Mrs Siraj: (…) It all came down to food, and who had food to share, and so we shared our things until the room was bare and mocking, still a secret, empty now, the hoard dispersed to hordes of worse-off folk[s] than us, the store exhausted twelve months in. But for that year we gave to poor and rich of every sort.

Sarah (voice over): You probably saved their lives.

Mrs Siraj: I doubt we saved their lives. We didn’t think dramatically like that. It was just the thing to do – to help and not to bat an eyelid doing so. Before the war we’d done the same, and when the war came, we stayed as we’d begun.25

Both Chong’s character in Roots and the character of Mrs Siraj in Occupation, anchored in real-life and performed in rich detail on stage, were conduits through which audience members could reach back through time and make sense of the histories that had come before, or witness a shift in perspective at something taken deeply for granted.

The Monodrama in Singapore Today

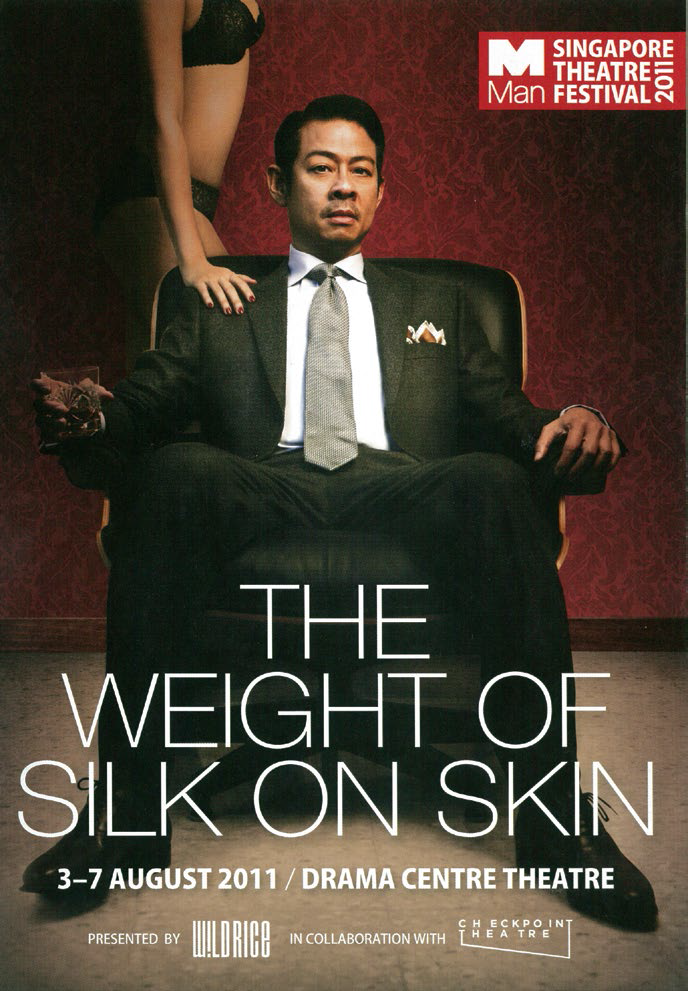

The 2010s have witnessed a flourishing of the monodrama, with well-received works such as Huzir’s The Weight of Silk on Skin (2011), where a well-heeled and erudite Singaporean man looks back at the loves and loves lost in his life; Chong Tze Chien’s To Whom it May Concern (2011), a fast-paced monodrama about Internet scams featuring an unreliable narrator; and young playwright Irfan Kasban’s 94:05 (2012), where a man on the cusp of an invasive surgery re-evaluates his role as father and husband.

Programme booklet of Huzir Sulaiman’s The Weight of Silk on Skin (2011), about a well-heeled and erudite Singaporean man, played by Ivan Heng, who looks back at the loves and loves lost in his life. Courtesy of Checkpoint Theatre.

Programme booklet of Huzir Sulaiman’s The Weight of Silk on Skin (2011), about a well-heeled and erudite Singaporean man, played by Ivan Heng, who looks back at the loves and loves lost in his life. Courtesy of Checkpoint Theatre.There have also been more recent group productions of short monologues such as The Theatre Practice’s Upstream (2015) and Teater Ekamatra’s Projek Suitcase (2015), featuring many young and upcoming practitioners. These intimate evenings of solo work also paid particular attention to the spaces they were performed in – Stamford Arts Centre and the Malay Heritage Centre respectively. Upstream, for one, was a farewell to The Theatre Practice’s long-time premises as the centre undergoes refurbishment and rebranding as a traditional arts space. The monologues presented were often laden with yearning and tinged with regret. Often, there was very little movement – one performer presented his half-hour work standing completely still. Another sat on a bench, his back to the audience for almost the entire performance.

Many of these recent monodramas were not inspired by their source material alone, but were buoyed also by a nostalgia for simpler storytelling times – a pre- Internet, pre-smartphone era. Director Alvin Tan wrote in his preface to Best Of (2013) that they wanted the audience to focus their full attention on the storyteller without the help – or perhaps the distraction – of sound, multimedia or technology:

“With our contemporary environment bombarded with high tech presences and our senses often preoccupied with the iPad, iPhone, Facebook and Twitter, we have lost much human interactive abilities. […] Can we ever listen deeply to another human being in person? Best of brings us back to storytelling basics. Just the storyteller and a chair.”26

For Roots (2012), creator Chong said in an interview with The Straits Times that he, too, wanted to bring the show back to the “roots” of theatre:

“I think we are forgetting what theatre can be. Because it all started with rituals and street performances, where they had nothing – just maybe a table and two chairs, and they could tell the whole play. I thought that was the beauty of theatre.”27

By going “back to basics”, theatremakers invite greater scrutiny of not just the quality of the solo performance – an ability to engage an audience, alone, and for an extended period of time – but also their narrators and central characters. Often, these protagonists, from Talaq to The Weight of Silk on Skin, are flawed and bruised. Each carries with them a compelling emotional nakedness, inviting the audience to help shoulder part of the burden they cannot bear.

This direct address, a hallmark of most monodramas, draws out the magnetic vulnerability of the single person on stage – regardless of whether the performer channels 12 characters or just one. And this, in turn, evokes a sense of communal empathy. A monodrama is nothing without its audience; it is only with the audience present, to listen, to seek to understand, that these characters – who in turn reflect the audience – can come to terms with their struggles and find some sort of inner peace.

Corrie Tan was the theatre correspondent and critic for The Straits Times, where she wrote on the performing arts and cultural policy. She also co-organised and sat on the judging panel of the annual M1-The Straits Times Life Theatre Awards. Her work has been published in journals such as Drama Box’s Draft, The Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, POSKOD and Ceriph.

Corrie Tan was the theatre correspondent and critic for The Straits Times, where she wrote on the performing arts and cultural policy. She also co-organised and sat on the judging panel of the annual M1-The Straits Times Life Theatre Awards. Her work has been published in journals such as Drama Box’s Draft, The Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, POSKOD and Ceriph.

NOTES

-

National Library Board. (2014, July 29). Chinese street storytellers written by Tan, Fiona. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Tan, C. (2014, September 30). Veiled digs at society and red tape. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brook, P. (2008). The empty space (p. 11). London: Penguin Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The monologue is a long speech by a single actor in a play or film, or as part of a theatrical or broadcast programme; the monodrama is an entire dramatic piece acted by a single performer. ↩

-

Lord, R. (2002, July) Konfrontation and konversion: Stella Kon gets her groove back. Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, 1(4). Retrieved from Quarterly Literary Review Singapore website. ↩

-

Tan, C. (2014, August 26). Turning the tide with Emily. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singaporean plays sought by ministry. (1985, September 19). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

柯思仁 [Quah, S.R]. (2013). 戏聚百年: 新加坡华 文戏剧 1913–2013 [Scenes: A hundred years of Singapore Chinese language theatre 1913–2013] (p. 13). Singapore: Drama Box & National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 792.095957 QSR) ↩

-

Untitled. (1892, December 5). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Freear’s Frivolity. (1892, December 14). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p, 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1911, December 12). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Humphrey Bishop Co. (1916, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Leyland Hodgson Company. (1920, June 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oon, V. (1972, September 29). Audience gets into the act as well. New Nation, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, C.K. (2004). Aesthetic strategies in the plays of The Necessary Stage. In C.K. Tan & T. Ng. (Eds), Ask not: The Necessary Stage in Singapore theatre (p. 72). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 792.095957 ASK) ↩

-

Tan, A. (2014). Foreword to Best of by Haresh Sharma. Singapore: The Necessary Stage. ↩

-

Hamilton, A. (2000). The rights of marriage. Asiaweek. Retrieved from Asiaweek website. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (2000, October 18). NAC ‘threatened’ to withhold play licence: Group. The Straits Times, p. 45. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hamilton, 2000. ↩

-

Oon, C. (2000, April 7). Sinister path to the power of the self. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chong, O. (2014). Roots: Reviews, script, essay, stills (p. 23). Singapore: The Finger Players. (Call no.: RSING 791.53095957 CHO) ↩

-

Tan, C. (2014, October 18). Heartfelt search for origins. The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from Newspaper. ↩

-

Rowland, K. (Ed.). (2013). Huzir Sulaiman: Collected plays, 1998–2012 (p. 31). Singapore: Checkpoint Theatre. (Call no.: RSEA 822 SUL) ↩

-

Huzir Sulaiman. (2013). Occupation. In K. Rowland. (Ed.), Huzir Sulaiman: Collected plays, 1998–2012 (p. 272). Singapore: Checkpoint Theatre. (Call no.: RSEA 822 SUL) ↩

-

Tan, A. (2014). Best of Haresh Sharma. Singapore: The Necessary Stage. (Call no.: RSING S822 SHA) ↩

-

Tan, C. (2012, November 21). Winding road to find roots. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩