In Remembrance of Reading

Our memories of reading are inextricably linked to the joy we derive from reading books and the places where we read them. Loh Chin Ee explains why.

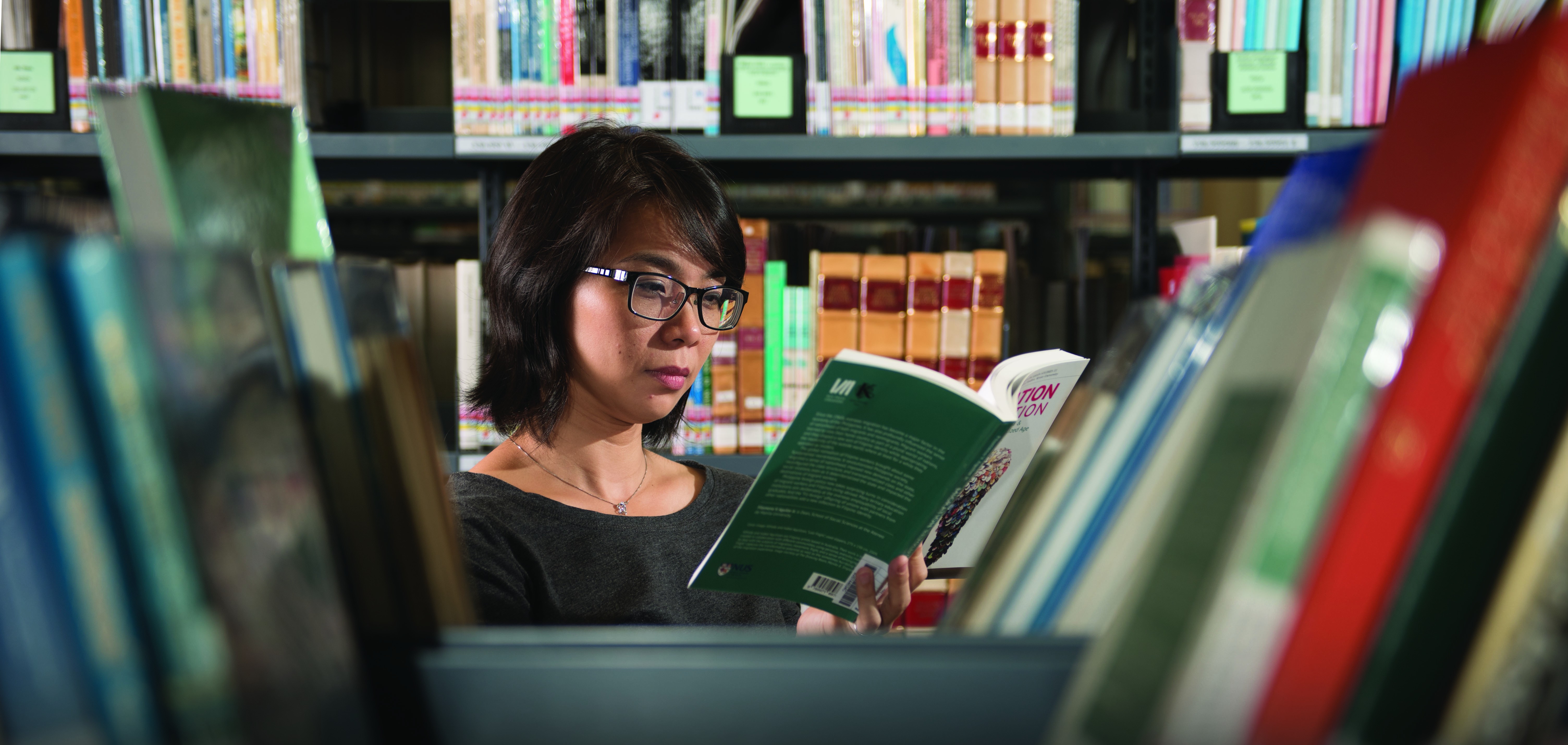

Dr Loh Chin Ee, shot on location at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at level 11 of the National Library Building. She read voraciously as a child and continues to do so as an adult. Dr Loh is an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Education, and specialises in reading and school libraries.

Dr Loh Chin Ee, shot on location at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at level 11 of the National Library Building. She read voraciously as a child and continues to do so as an adult. Dr Loh is an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Education, and specialises in reading and school libraries. My first concrete memory of reading is of me sitting on the floor of my school library, completely immersed in the pages of the book my head was buried in. I can’t recall the title of the book, but I remember my single-minded absorption in the story, and the mild irritation felt when the bell rang to signal the end of recess.

The library at Marymount Convent School was on the first floor, wedged midway between my classroom on the second floor and the canteen in the basement. It seemed like a huge space full of books to a 9-year-old but looking back now, it was probably about the size of three large classrooms. It was here where I borrowed books by Enid Blyton and read about the adventures of Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys. Some of my favourite books tucked away on the shelves included Black Beauty by Anna Sewell, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series and L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Years later, another memory etched in my mind is that of fighting sleep in order to read the mammoth A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth in 24 hours – one of the many books I hungrily devoured when I had plenty of time on my hands after the A-level exams.

In Janice A. Radway’s classic ethnographic study, Reading the Romance,1 she examines the reading habits of a group of housewives in small-town America. For these women bound to the home, reading romantic fiction served as a form of escapism and pleasure from their mundane lives revolving around the house and children. They saw it as a form of education (transporting them into exotic – and sometimes erotic worlds – that they would have little chance of experiencing); therapy (providing respite from housework and boredom); and community (allowing them to converse with other like-minded readers). While not everyone enjoys reading romance novels, Radway’s study illustrates how reading can serve multiple purposes of education, edification and entertainment. That reading can provide endless hours of entertainment or transform one’s worldviews likely accounts for the significance that people attach to their memories of reading and of books.

Remembering Books

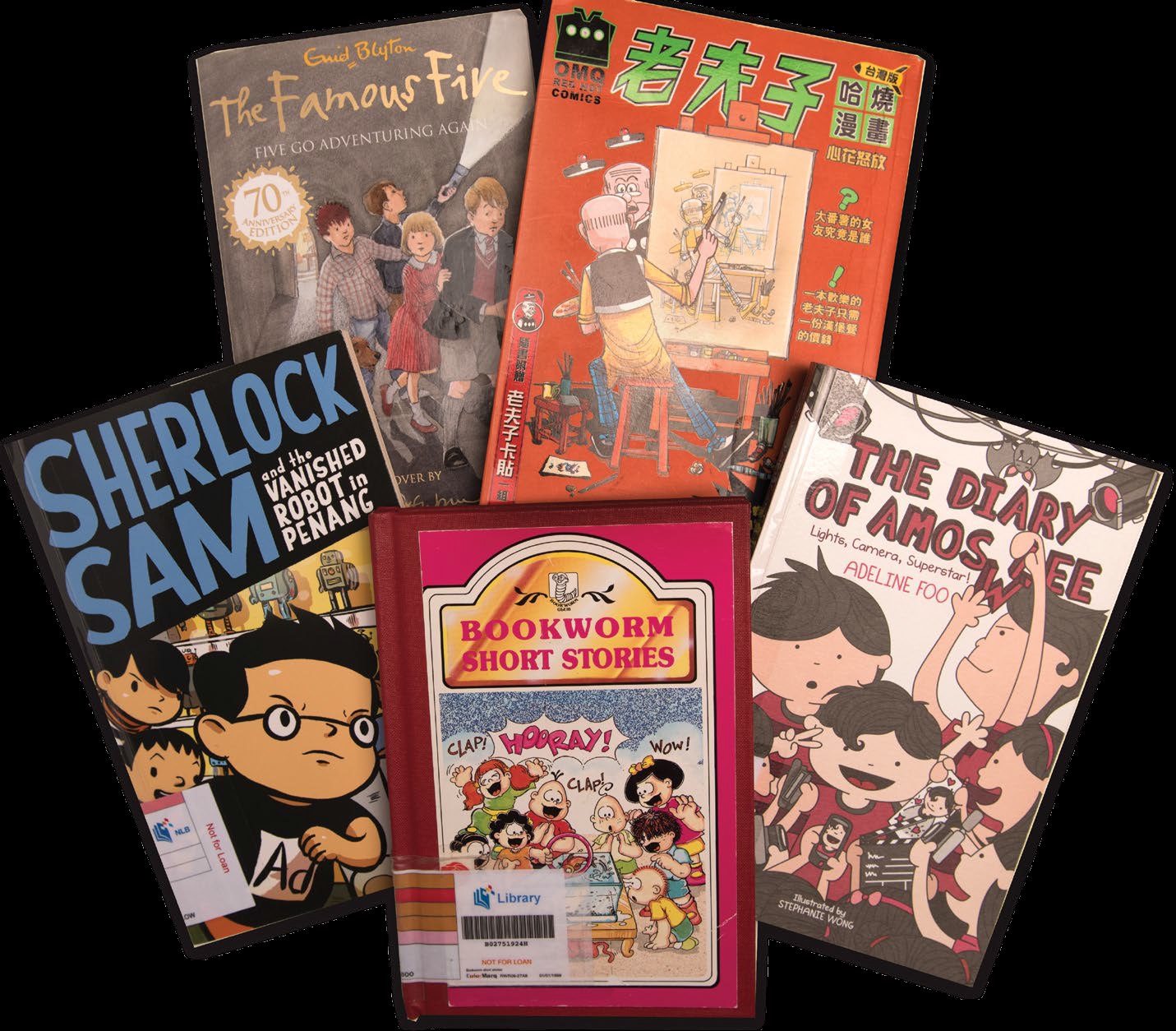

Trawling through the Singapore Memory Project,2 I discover echoes of my own memories in the memories of others. People shared their memories of reading The Adventures of Mooty3 and being hooked on the Bookworm Club series4 both published in Singapore. The latter series was a regular publication in the 1980s and 90s, featuring the adventures of Sam Seng, Simone, Porky, Mimi and Edison in locations that were distinctly Singaporean. The Bookworm Club was innovative in its ability to generate a sense of excitement about reading through school assembly talks and membership subscriptions. I was an avowed Bookworm fan, and at primary four or five, made the pilgrimage with some friends to its office on Selegie Road to buy backdated issues. Students today have greater access to children’s and young adult’s literature by local authors. Some recent Singapore bestsellers include The Diary of Amos Lee by Adeline Foo and the Sherlock Sam series by the husband-and-wife team Adan Jimenez and Felicia Low-Jimenez – both published by Epigram Books.

This selection of books from The Famous Five to Lao Fu Zi and the Bookworm Club series to the more contemporary Sherlock Sam and The Diary of Amos Lee represent popular reading tastes from the different decades.

This selection of books from The Famous Five to Lao Fu Zi and the Bookworm Club series to the more contemporary Sherlock Sam and The Diary of Amos Lee represent popular reading tastes from the different decades.Each generation has its own memory of particular genres and particular books. Singaporeans in their late-20s and early- 30s would have been spellbound by Harry Potter books; the long lines snaking outside Borders bookshop in the early to mid- 2000s is a sight many still remember. While I was not one of those who stood in line, I had friends who followed the series (first the book, then the movies) rabidly. Enid Blyton still remains a consistent favourite among primary school children, although parents might be surprised to find their children reading revised – read politically correct – versions of The Famous Five, with the language updated for modern audiences.5

Students from the 1970s to 90s would be familiar with the comic series Lao Fu Zi (老夫子), or Old Master Q in English – created by Alfonso Wong in 1962. Students found the stories so engrossing that even those with a shaky grasp of Chinese, such as me, read the simple comics for their illustrations and humour. T. C. Lai recalls that he “grew up in the 70s reading Lao Fu Zi all the time, whether it was at clinics, barber shops or bookshops in South Bridge Road”. He enjoyed the “scenes… of Lao Fu Zi (and his sidekicks) dealing with gangsters dressed in bell-bottom pants and garish print shirts”.6 Actor Edmund Chen, now in his 50s, recalls that wuxia (武俠), or swordfighting novels, were his reading staples during his Catholic High School days (see profile below). But for Wan Zhong Hao, in his mid-20s, a generation later at the same school, manga comics were the rage, along with Tin Tin and Asterix and Obelix comics. These books allowed readers to immerse themselves in the parallel story worlds, and enabled them to follow their favourite characters through their adventures, dilemmas, and sometimes, even growth.

Reading Places

Libraries and bookshops rank highly in Singaporeans’ memories of places of reading. While each generation remembers different libraries and bookshops, these places remain constant in the memories of the diverse generations. The collective memory of the National Library at Stamford Road generated unprecedented civic activism between 1999 and 2000 when many Singaporeans protested over its proposed demolition to make way for the Singapore Management University and a tunnel to redirect traffic.7 Even though the quest for “progress” prevailed and the red-bricked building was eventually torn down in 2005, people of a certain generation still remember it fondly. It would seem that the old National Library, more than any other institution in Singapore, symbolised the nation’s love for reading.

Opened in 1960, the original National Library at Stamford Road was for many years a source of entertainment and education for many Singaporeans. People visited the library to borrow and read books, and parents could safely leave their children in the children’s section while they browsed in the adult section, all on the ground floor. The library became the haunt of students from the various schools in the Civic District – students from Raffles Institution, Raffles Girls’ School, Victoria School, Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus and St Joseph’s Institution hung out at the library to socialise and to study. Reflecting on his time spent in the National Library as a teenager and later, as an adult, poet and essayist Boey Kim Cheng writes that the library is a “storehouse, not only because each book it contains is a work of memory, but more vitally because it contains the memory loci for readers whose lives have been changed by it”.8

Places are repositories of both individual and collective memories; the sounds, the smells, the feelings evoked by the old National Library are part of our recollections of what the building represented. The iconic but austere building – typical of the functional post-war Modernist architecture of the period – with its concrete steps leading up to the balustrade and main entrance, the slightly musty smell of books, the tattered library card that promised a treasure trove of books (four to be exact) that could be borrowed are some memories that Singaporeans over the age of 30 share. For the younger generation, their memories of reading are associated with the modern glass-and-steel building on Victoria Street or with the new and shiny public libraries found all over Singapore.

Bookshops are also often associated with reading. In the 1960s and early 70s, parents with their school-going children in tow would head to independent bookshops along Bras Basah Road – bearing names like Sultana and Modern – before the start of the new school year to buy freshly minted textbooks. The mother of all bookshops was MPH, established in 1815 in Malacca and later moving to Singapore in 1890. MPH has gone through several name changes, from Methodist Publishing House to Malaya Publishing House, then Malaysia Publishing House. Entering the scene much later was Times the Bookshop in 1978, Kinokuniya in 1983, and of course Borders in 1997, which has since exited the retail scene.

In a less wealthy Singapore, secondhand bookshops also thrived as hubs of pleasure for avid readers. Secondhand books could be bought for a fraction of the original price, read and then returned in exchange for another book at a reduced price. In secondary school, when I was permitted to roam about by myself after school hours, I would visit Sunny Bookshop in Far East Plaza or patronise a small secondhand bookshop in Ang Mo Kio Central Market and Food Centre, usually on my way to the Ang Mo Kio Public Library. The iconic Sunny Bookshop closed in August 2014. Bank analyst Lynn Teo, reflecting on the imminent closure of Sunny rued its loss, writing: “I feel like another piece of my ‘growing up’ is gone… I remember taking hours to decide which romance novels I wanted to rent and counting if I had enough money to take out more than one book at a time. I… definitely miss it.”9

The Edwardian-style Methodist Publishing House building at the junction of Stamford Road and Armenian Street opened in 1904. It was subsequently renamed Malaya Publishing House and then Malaysia Publishing House. MPH bookshop has since moved out of this location, but for nearly a century this was the grand dame of the bookshop scene in Singapore. (The Singapore Management University currently leases the building.) This 1984 image is from the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

The Edwardian-style Methodist Publishing House building at the junction of Stamford Road and Armenian Street opened in 1904. It was subsequently renamed Malaya Publishing House and then Malaysia Publishing House. MPH bookshop has since moved out of this location, but for nearly a century this was the grand dame of the bookshop scene in Singapore. (The Singapore Management University currently leases the building.) This 1984 image is from the Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.For Chinese books, readers would go to Chinese bookshops in Golden Mile Complex and the various independent bookshops in Bras Basah Complex. Yam Chiang Yee recalls visiting these shops as a young child, where “some of the poor would sit on the floors of the bookshop to read. Back then, the bookshop owners were… very understanding and didn’t chase them away”.10 The now ubiquitous Popular began as a Chinese bookshop in 1936 on North Bridge Road, and moved to Bras Basah Complex when it opened in 1980. The presence of so few independent bookshops today represents an erosion of the reading culture in Singapore.

Reading as Social Practice

While reading is often perceived as a solitary activity, there is in fact much social interaction that takes place around reading and readers. In a speech made at the 10th anniversary celebration of KidsRead, a National Library Board (NLB) programme where volunteers read to children of low-income families, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong shared how his mother, the late Madam Kwa Geok Choo, used to read to him as a child.11 A favourite book was The Story About Ping, about a duckling living with his family on a boat on the Yangtze River. Reading, as this case illustrates, becomes pleasurable parent-child bonding time over stories. It is also a form of apprenticeship, where parents teach (often without trying) their children how to read and to engage in reading for pleasure.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s mother, the late Madam Kwa Geok Choo, used to read this book to him as a child, about a duckling living with his family on a boat on the Yangtze River. All rights reserved, Flack, M., & Wiese, K. (2014).The Story About Ping. New York, USA: Grosset & Dunlap.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s mother, the late Madam Kwa Geok Choo, used to read this book to him as a child, about a duckling living with his family on a boat on the Yangtze River. All rights reserved, Flack, M., & Wiese, K. (2014).The Story About Ping. New York, USA: Grosset & Dunlap.When Borders was launched, it tried to create a community of readers. It brought a different concept of the bookshop experience to Singaporeans, encouraging browsing and reading within its premises with books that were not shrink-wrapped and providing sofas and arm chairs for this express purpose – although many chose to sit (or sprawl) on the carpeted floors to read. Borders was ahead of its time in Singapore, organising various activities such as book launches and book discussions and workshops to engage the community in reading.12 The presence of Borders resulted in the transformation of the bookshop landscape with MPH and Times revamping their store layouts and Japanese book retailer Kinokuniya expanding its business in Singapore with a capacious outlet at Ngee Ann City in 1999. Although Borders closed in 2011, in part due to poor sales as well as the declining fortunes of its parent company in Australia, it helped significantly in repositioning the entertainment value of reading in Singapore.

Book clubs are another example of how reading can be very much a social activity. Read! Singapore, launched in 2005, is a nationwide initiative by the NLB. Featuring a multilingual annual book list, author sessions and book clubs, the initiative aims to generate excitement about reading. The annual Singapore Writers Festival, first organised in 1986, is another example of an initiative that aims to encourage reading and conversations around books.13 Independent bookshops such as Caogen (草根书室) and Books Actually continue to thrive, partly because they value their community of readers and create opportunities, whether through book launches or café spaces, for the community to meet. Readers want to see themselves as part of a wider social network and have conversations around books they have read. These conversations can add another layer to the experience of reading.14

The idea of having conversations around what one’s friends and contemporaries are reading is not new. In the 1950s and right until the 70s,15 the Malay community in Singapore participated in “group reading of the newspapers”, passing the papers from “one hand to another or father to son”. It was common for individuals to congregate in village spaces, and later coffeeshops, to discuss social issues relating to what they had read. This culture of newspaper reading and coffeeshop talk among older generations of Singaporeans has survived and even spread to other communities – my father, for instance, now retired, takes a daily walk to the nearby coffeeshop to have his morning coffee and read his Chinese newspaper.

The post-war communal reading habits of older Singaporeans thrive to this day. It is not uncommon to see retirees sitting in coffeeshops or the void decks of HDB flats reading their newspapers in the morning.

The post-war communal reading habits of older Singaporeans thrive to this day. It is not uncommon to see retirees sitting in coffeeshops or the void decks of HDB flats reading their newspapers in the morning.While how we buy and read books today has changed with the presence of online book retailers such as Amazon and Book Depository and e-readers like Kindle and iBooks, reading remains very much alive in the 21st century. The Internet is abuzz with online reading communities that provide opportunities for people to discuss, share and recommend their latest reads. Digital books are downloaded instantaneously on e-readers, especially convenient when travelling. Yet, the printed book remains a popular option,16 informal books clubs continue to thrive and book-related media events continue unabated. Technology, therefore, supports and encourages the reading of the printed book, and libraries and bookshops are reinventing themselves as places not just to access books, but also to engage in social activities around books. Our memories of reading are closely intertwined with the relationships and conversations that are built around books and the places that allow us to indulge in reading.

Edmund Chen is a multi-talented artiste who is well-known in Singapore as an actor, director and producer. Much less publicised is the fact that he is also a gifted storyteller and illustrator who has designed a series of stamps for SingPost (the otter and panda series), set a Guinness World Record for “The Longest Drawing by an Individual” (at an impressive 601 metres), and published several Chinese-language children’s books.

Edmund, who is equally comfortable in both English and Chinese, credits his affinity for the Chinese language to his time at Catholic High School, where he studied Chinese as a first language. He remembers reading wuxia, or swordfighting novels, for entertainment in secondary school. His favourite novels include The Legend of the Condor Heroes (神鵰俠侶) and The Duke of Mount Deer (鹿鼎记), both by Jin Yong (金庸), and a series of seven wuxia novels centred around the character Lu Xiaofeng (陆小凤) by the Taiwanese novelist Xiong Yaohua (熊耀华) under the pen name Gu Long (古龙).

Wuxia novels flourished in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in the 1950s and the earliest wuxia were distributed via newspapers. In the 1970s and 80s, it was a popular genre among teenagers and adults in Singapore, partly for its treatment of serious themes such as chivalry, historicism and nationalism. Well-known filmic explorations of the wuxia genre include Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (卧虎藏龙) and the Once Upon a Time in China series starring Hong Kong actor Jet Li as folk hero Huang Feihong (黄飞鸿) and directed by Tsui Hark.

As an actor, Edmund read to “understand the different roles” he had to play. Reading reminds him not to be so narrowminded, to see things from new perspectives and to understand others. More recently, he initiated an SG50 project, Ah Cai Kopi (阿财 搅咖啡), where he produced and co-hosted a multilingual talk-show on web television that featured some of Singapore’s top personalities and professionals. Part of his preparations included reading about the history of the media industry and the personalities he interviewed.

As a father, the first book Edmund read to his daughter was a book that he wrote called Xiao Qing’s Story (小青的故事), about a proud bird of paradise that learnt not to judge other animals by their appearances. Set in Malaysia, this book was one of a series of four books about endangered animals (the others being the whale, rhinoceros and proboscis monkey). Through these books, Edmund wanted to create awareness of endangered species and encourage children to protect such animals. Edmund feels that reading should be both enjoyable and educational, and writing stories is a way for him to impart strong moral values to young readers.

Ever the sentimental person, Edmund has two rented storerooms where he stores some of his most treasured books. His collection includes some of his old comics, wuxia novels and the books he used to read to his children.

Myra’s enthusiasm for reading is contagious. As the co-founder of Gathering Books (gatheringbooks.org), a website celebrating books, an organiser of the Asian Festival of Children’s Content, and the enthusiastic leader of three book clubs in Singapore, much of Myra’s waking hours are spent reading and promoting books. All this is in addition to her busy day job as Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Education, where she specialises in the study of gifted children.

An avid reader since young, reading is “like breathing” for Myra, an absolute necessity. She shares that reading has enriched her life, heightened her senses and made her more grateful to be alive. For Myra, the most wonderful part about reading is that the experience of reading is available free (from the library), or at a reasonable price (at a bookshop). Over and above the pleasure it provides her, Myra believes that reading gives one a sense of clarity and meaning, and allows us to reflect on the kind of lives that we should lead.

Reading groups are a social phenomena where individuals gather, whether online or physically, to talk about books. Gathering Books started out as a book club in 2007, and Myra was inspired to set up the website in 2010 when she moved to Singapore from the Philippines, as a resource for teachers and parents (and bibliophiles) looking for book titles they wish to share with their students or children. The site is regularly updated by Myra and her collaborators and contains catchy banners such as “Sunday Book Hunting Expeditions”, “It’s Monday, What are you reading?”, “Nonfiction Wednesday,” “Saturday Reads” and “Poetry Friday”.

Currently, Myra is involved in three book clubs in Singapore that meet on a regular basis. Inspired by her daughter, the first club (Gathering Readers) was started in 2012 for tweens from 10 to 15 years old – the age range is adjusted as her daughter gets older – and is held at the Jurong West Public Library. The second book club (Saturday Night Out for Book Geeks) comprises a motley ssortment of published (and aspiring) local and foreign authors, illustrators, librarians, art critics, comic geek enthusiasts and educators. The newest reading group (Gathering Readers at NIE) is made up of fellow colleagues from different departments at the National Institute of Education. This is what Myra calls her “book tribe”, a community of readers who share her love for reading.

When I asked Myra about how she finds time to do all that she does, she quotes sagely from the poet Rumi: “When you do things from your soul you feel a river moving in you, a joy.” She is one of those fortunate individuals where the dividing line between passion and work has become blurred – in a good way.

The family that reads together: Mum Adeline Lee, dad Eng Kiat and their brood of three avid readers, Christabel, aged 12 (left), Isabel, aged 14 (right) and the youngest, eight-year-old Estherbel, in the middle. Photographed on location at the Central Public Library, National Library Building.

The family that reads together: Mum Adeline Lee, dad Eng Kiat and their brood of three avid readers, Christabel, aged 12 (left), Isabel, aged 14 (right) and the youngest, eight-year-old Estherbel, in the middle. Photographed on location at the Central Public Library, National Library Building.

The Lees are the ultimate poster family for intergenerational reading. In an interview at the Clementi Public Library, they talk about the role of reading in their lives. Mum, Adeline, began the journey with the girls when she decided to use a Christian homeschooling kit called the “American Classical Education” to supplement her children’s education. Using the booklist provided, she bought her children books and read to them – and with them – from an early age. She believes that it’s important to push the children’s reading “to proficiency level” after which they can be left to read and pursue knowledge on their own.

Reading habits differ in the Lee family. Eldest daughter Isabel, aged 14, shares her mother’s love for classics, historical fiction and award-winning books. Isabel’s favourite author is Gerald Durrell “who writes about animals”. Second daughter Christabel, aged 12, shares her father Eng Kiat’s love for comics, science fiction and fantasy, and is currently reading the Warrior Cat series by Erin Hunter. Adeline and Isabel cannot understand Eng Kiat’s and Christabel’s fascination with The Hobbit and Star Wars series of books.

Eight-year-old Estherbel, the youngest, prefers watching television but enjoys listening to audio-books; her favourite series at the moment being Sophie’s Adventures by Dick King-Smith and illustrated by David Parkins. Isabel and Christabel have read so widely that they were able to represent Singapore in the Kids’ Lit Quiz, an annual literature competition for students aged 10 to 13, in 2013 and 2014 respectively.

When probed further about their love for reading, it became clear that the family’s habit of book collecting and library trawling was passed down from Adeline’s parents. Adeline remembers growing up with shelves full of Reader’s Digest at home, which she and her brother Gary would read voraciously. This was in addition to the books they would borrow when their mother dropped them off at the Queenstown Public Library. These days, Adeline has stopped buying books for her children due to the lack of space at home. In any case, “the public libraries have everything” and visiting the library allows each child the freedom to select her own preferred books.

The family’s dedication to reading is evident in their daily lives. During meal times, the girls are allowed to read at the table, and it is not unusual to find family members ensconced in their own rooms reading whenever they are free. The Lees frequently share and swop ideas on books: Christabel remembers Isabel recommending that she read Regarding the Fountain by Kate Klise and Holes by Lousi Sacher when she was in primary 4. Isabel is presently reading books by Jane Austen, a recommendation by her uncle Gary, currently a literature professor based in the US. As the children live in the same household as their maternal grandparents, they have access to the vast collection of materials that three generations of readers have amassed.

When it comes to reading, Adeline and her brother Gary firmly agree that “if you cut out all the electronic devices and allow the kids to be bored, the kids will naturally turn to reading for entertainment”. At the magical point where forced reading becomes voluntary reading, children discover the freedom to entertain and to gain knowledge for themselves.

NOTES

-

Radway, J. A. (1991). Reading the romance. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The Singapore Memory Project is a whole-of-nation movement that aims to capture and document precious moments and personal memories related to Singapore. See www.singaporememory.sg portal ↩

-

Liew, H. (2015, October 7). Simple joys of my childhood [Web log post]. Retrieved from irememberSG website. ↩

-

Goh, M. (n.d.). Bookworm Club membership [Web log post]. Retrieved from irememberSG website. ↩

-

Flood, A. (2010, July 23, 2010). Enid Blyton Famous Five get 21st-century makeover. The Guardian. Retrieved from The Guardian website. ↩

-

Teo, J. (2011, November 17). Old Master Q (老夫子) [Web log post]. Retrieved from The Elusive Sleuth website. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2014, June 21). What future for our past? The Straits Times. Retrieved from AsiaOne website. ↩

-

Boey, K.C. (2014). The library of memory. Biblioasia, 10 (1), pp. 3–7. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Sunny Bookshop to close down in August 2014. (2014, August 4). Yahoo News. Retrieved from Yahoo! News website. ↩

-

Yam, C. (2013, December 20). 百胜楼. Retrieved from Singapore Memory Project website. ↩

-

Yong, C. (2014, October 4). PM Lee reads story book to children, extends reading programme for less privileged. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014, January 28). Borders (Singapore) written by Goh, Kenneth. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Singapore Writers Festival. (2015). Singapore Writers Festival: Island of Dreams. Retrieved from Singapore Writers Festival website. ↩

-

Fuller, D., & Sedo, D.R. (2013) Reading beyond the book: The social practices of contemporary literary culture. NY: Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Ainon Kuntom. (1973). Malay newspapers, 1876 to 1973: A historical survey of the literature (p. 48). (Call no.: RSING q079.5951 AIN) ↩

-

Darton, R. (2011, April 17). 5 myths about the information age. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from The Chronicle of Higher Education website. ↩