Singapore TV: From Local to Global

Lau Joon-Nie charts the rise of Singaporean television from the first test transmissions to the advent of foreign competition posed by the arrival of cable.

“Tonight might well mark the start of a social and cultural revolution in our lives,” said then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, the first person to appear on national TV when he launched Television Singapura at the Victoria Memorial Hall on 15 February 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

“Tonight might well mark the start of a social and cultural revolution in our lives,” said then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, the first person to appear on national TV when he launched Television Singapura at the Victoria Memorial Hall on 15 February 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Mention Growing Up to any 30-something Singapore TV fan and watch his or her face light up with a wistful look of nostalgia. Singapore’s longest-running English language drama series – which debuted in 1996 and ended its run in 20011 – ran for six seasons, detailing the ups and downs of the fictional Tay family who lived through the 1960s to the 80s. Viewers lapped up the meticulously recreated scenes of yesteryear with its retro outfits and hairstyles, and carefully curated furniture, cash registers, telephones, radio and TV sets, and other such miscellany of the period.

By coincidence, the Tay family grew up in an era when television first made its foray into Singapore. 15 February 1963 was a momentous day for TV in Singapore when the government started a pilot service, following a feasibility study in the 1950s2 and a series of test transmissions before the official launch. “Tonight might well mark the start of a social and cultural revolution in our lives,” said then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, the first person to appear on national TV when he launched Television Singapura at the Victoria Memorial Hall.

Growing Up was Singapore’s longest-running English drama series and lasted six seasons from 1996 to 2001. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.

Growing Up was Singapore’s longest-running English drama series and lasted six seasons from 1996 to 2001. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.Outside, thousands had gathered in anticipation to watch the first black-and-white TV images come to life on a few dozen TV sets placed around Empress Place for the occasion. The first programme aired at exactly 6.05 pm was a 15-minute documentary, TV Looks at Singapore, introducing the concept of television and its impact on the lives of Singaporeans. This was followed by two cartoon clips, news in English, a comedy skit and a variety show titled Rampaian Malaysia (“Malaysian Mixture”). Transmission ended at 7.40pm.3

At the time of the launch in 1963, just 8 percent of households owned a TV set.4 For those without one, 50 public viewing points were set up across the island, at places such as community centres. Within six months, the Channel 5 broadcasts in English and Malay increased from a weekly one-hour programme to five hours a day on weekdays and 10 hours a day over the weekend. Channel 8 was launched in November that same year with programmes in Mandarin and Tamil. By 1965, all programming was handled by Radio and Television Singapore (RTS), under the Department of Broadcasting of the Ministry of Culture.

Colour Comes to Singapore

Singaporeans were ecstatic to be among the first in Southeast Asia to enjoy colour broadcasts in mid-1974, snapping up home colour TV sets during the first 10 weeks of its launch. Not all programming was available in colour though. Newscasts only went full colour during phase two of the roll-out in November that year. Colour TV sets soon replaced black-and-white ones at the community centres, the five-year roll-out costing S$8 million.

By the mid-1970s, entertainment accounted for about 74 percent of the content broadcast across RTS’ combined programme schedules, with drama forming the bulk, followed by variety shows. Most content – about 60 percent – was imported, mainly from North America. Older viewers will fondly recall popular detective shows such as Hawaii Five-O, Toma and Mannix. Soon enough, the influx of imported programmes, particularly crime dramas, was blamed for the rise in violence and delinquency among Singapore’s youth.

The authorities drew this spurious conclusion based on figures from agencies such as the Prisons Department and Reformative Training Centre. This led to the scheduling of several violence-free days of programming. Mondays, Tuesdays and Fridays saw dramas such as The Six Million Dollar Man, I Love Lucy and The Waltons taking up prime time slots. Unbeknownst to Singaporeans, they were watching fewer American police and detective shows than their counterparts in Southeast Asia, even as US shows remained the most affordable to buy. Television Singapore had a US$1.2 million a year acquisition budget in the mid-70s to buy content from overseas.5

For the remaining 40 percent of content that was produced locally, the Chinese Variety Show and Malay Pesta Pop proved to be hits. There were also Singaporean family magazine shows featuring everything from personality profiles to flower arrangement demonstrations. Without the pressing bottomline concerns that plague corporate broadcasters today, officials had the luxury of ignoring the game-and-quiz show format, preferring to maintain a low commercial profile instead.

When it came to factual content, RTS had a central production arm for civics and international affairs programmes. It produced radio and TV current affairs programmes such as talks, interviews, discussions and documentaries that were aired during prime time.

Then Minister for Culture Jek Yeun Thong tours the colour television studios at Radio and Television Singapore in 1974. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Then Minister for Culture Jek Yeun Thong tours the colour television studios at Radio and Television Singapore in 1974. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Greater Autonomy

However, bigger changes were afoot. On 1 February 1980, RTS was restructured into a statutory board called the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (SBC). This would free RTS from governmental administrative and budgetary constraints that hampered it from upgrading its production facilities and skills pool. With its newfound flexibility in hiring and procurement, SBC increased its staff strength from 1,335 to 1,648 and spent S$8.6 million on new infrastructure and technology in its first year, including a new radio transmission tower at Bukit Batok and electronic news gathering equipment.6

Then Acting Minister for Culture Ong Teng Cheong said in a newspaper interview that the idea of a semi-government radio and TV station was first mentioned in 1966, “but because of manpower resources and other more urgent requirements in other sectors of the country, it dragged on for so long”. While SBC was formed to liberate the old RTS from the bureaucratic shackles that had long impeded its development, the new entity would continue playing an important role in nation-building and communicating government policies and objectives. Ong was appointed chairman of SBC, with the government categorically stating that it would “retain control over the policy of the corporation in the public interest” to ensure that air time for minorities would not be reduced.7 There was some loosening of control, however, when changes were made to reduce the amount of public service broadcasting and messaging SBC would have to carry. These programming changes enabled more advertisements to be sold, raising revenue rapidly and laying the groundwork for subsequent privatisation.

The changes also paved the way for more local programmes. In 1984, SBC launched a third free-to-air channel, SBC 12, to meet the need for more Malay and Tamil programming, children’s content, and foster an appreciation for arts and culture. Much of the children’s and minority programming was produced by SBC. In 1994, the Media Development Authority (MDA) began awarding rants to production houses to increase the number of hours of locally made public service broadcasting and grow the media industry.8 Funding came from the mandatory radio and TV licence fee paid by every household and vehicle owner. When this fee was abolished in 2011, the government maintained its commitment to funding such content, and this has in fact increased since.9

Turning Point

By the early 1990s, moves were underway to prepare the broadcast industry for the inevitable influx of foreign competition. While the government would not budge on allowing residential households to own TV satellite dishes,10 it did, however, permit SBC to launch the country’s first pay TV channel, NewsVision. This was done through the creation of Singapore Cable Vision (SCV), a 65:35 percent tie-up with Temasek Holdings-owned Singapore International Media and SBC in 1991.11

NewsVision began transmission on 2 April 1992, providing 24-hour news mainly from CNN, with some newscasts from Independent Television News and SBC’s 9 pm bulletin. This broke SBC’s local monopoly over TV news and for the first time, the public had access to foreign news broadcasts on local TV. Two other subscription channels, MovieVision and VarietyVision, were launched on 1 June 1992. All three channels were transmitted on the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) band, which was not ideal given that 80 percent of the population lived in high-rise buildings, affecting signal reception.12 Viewers also did not warm up to the high monthly subscription costs.

The launch of these early pay TV channels proved unnecessary when in the same year, the government announced the nationwide cable TV roll-out as part of a wider plan to wire Singapore for the Information Age. SCV won the bid to build the hybrid-fibre coaxial network and in a nod to its massive cabling effort, it was granted the right to be the exclusive provider of pay TV services until June 2002.13 In June 1995, SCV launched its cable TV pilot in 10 public housing blocks in Tampines, offering subscribers an unprecedented broadcast buffet of over 25 channels. Non-subscribers could receive their regular free-to-air channels by simply plugging their TV sets into the cable points in their homes and not be at the mercy of the weather for clear TV reception. Today, this is how we watch free-to-air content now that all local channels are fully digital.

Local Drama and Sitcoms Take Off

In the year before SCV launched its cable TV pilot project, a major restructuring of the local broadcast industry took place. In 1994, SBC was corporatised to form Singapore International Media (SIM), theparent company of Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS), Singapore Television 12 (STV12) and Radio Corporation of Singapore (RCS). These newly created corporate structures gave the respective entities greater autonomy and flexibility in making strategic business decisions. Both Channel 5 and Channel 8 started 24-hour transmission in 1995, and STV12 was revamped that year into two channels: Prime 12 for Malay and Tamil programming, and Premiere 12 for arts, documentaries and children’s programmes. Singapore now had four TV channels. Local production flourished during this time. Between 1994 and 1995, local output increased by 60 percent, with the Mandarin Channel 8 producing an average of 600 hours of sitcoms, dramas and variety shows each year, thus making TCS one of the most prolific stations in the world.14

Chinese drama production in Singapore began in earnest in 1983 with the setting up of SBC’s Chinese Drama Division, resulting in hundreds of serials since. What is officially regarded as the first locally produced Mandarin drama, the 50-minute long The Seletar Robbery, was actually filmed a year earlier.15 When the 1979 Broadcasting Act limited the amount of foreign programming allowed on TV, SBC was spurred to nurture its own team of actors, directors and scriptwriters. Specialists from Hong Kong and Taiwan were recruited to work and train the local staff. The Chinese Drama Division’s first major success was The Awakening (雾锁南洋) in 1984, a highly popular series about the toils and troubles of Singapore’s early Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. Indeed, local dramas became such a staple that by 1987, they were telecast five nights a week on Channel 8.16 SBC also developed an overseas market for its dramas, selling them to broadcasters and home video distributors regionally. This has become so successful that, today, thousands of hours of content are sold to partners in Australia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, in the process increasing the profile and popularity of our home-grown stars.17

SBC’s Chinese Drama Division’s first major success was The Awakening (雾锁南洋) in 1984, a highly popular series about the toils and troubles of Singapore’s early Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.

SBC’s Chinese Drama Division’s first major success was The Awakening (雾锁南洋) in 1984, a highly popular series about the toils and troubles of Singapore’s early Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.English-language dramas in Singapore had a rockier start. The English Drama Division was set up in the early 1990s and produced its first series, Masters of the Sea (1994) with the help of Joanne Brough, a former executive producer of the hit American soap operas Dallas and Falcon Crest, and a team of foreign writers.18 However, local viewers were unable to relate to the tumultuous tale of a wealthy Chinese shipping family and decried it for its lack of authenticity and local actors who spoke with fake British and American accents.

Eventually, producers struck the right chord with viewers with Under One Roof (1994), about “Singapore’s funniest family” living in a public housing estate in the middle-class suburb of Bishan. Under One Roof ran for nine years and remains one of TCS’ greatest commercial successes, garnering multiple wins at the Asian Television Awards over its seasons.19

Under One Roof, about “Singapore’s funniest family” living in a public housing estate in the middle-class suburb of Bishan, ran for nine years and remains one of TCS’ greatest commercial successes, garnering multiple wins at the Asian Television Awards over its seasons. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.

Under One Roof, about “Singapore’s funniest family” living in a public housing estate in the middle-class suburb of Bishan, ran for nine years and remains one of TCS’ greatest commercial successes, garnering multiple wins at the Asian Television Awards over its seasons. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.In 1996, TCS struck gold again with Growing Up, which “was praised for its convincing performances, high-quality scriptwriting and credible depiction of Singapore in the formative post-separation years”.20 Buoyed by its success, the English Drama Division went on to tackle modern-day themes, churning out a series of shows around corporate and “dot.com” lifestyles such as Three Rooms (1997), VR Man (1998) and Spin (1999). These, however, gave way to local sitcoms as audiences sought relief from the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. Phua Chu Kang (1997) rode on this wave, cheering up audiences with its delightfully subversive storylines that appeared to go against the grain of governmental exhortations, e.g. to speak good English, have (more) children, and work hard.21 Audiences embraced the loveable Singlish-speaking contractor, Phua Chu Kang – “the best in Singapore, JB and some say Batam” – and his dysfunctional family members for 10 years, making the show Singapore’s longest-running English-language sitcom.

Audiences embraced the loveable Singlish-speaking contractor, Phua Chu Kang – “the best in Singapore, JB and some say Batam” – and his dysfunctional family members for 10 years, making the show Singapore’s longest-running English-language sitcom. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.

Audiences embraced the loveable Singlish-speaking contractor, Phua Chu Kang – “the best in Singapore, JB and some say Batam” – and his dysfunctional family members for 10 years, making the show Singapore’s longest-running English-language sitcom. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.Making News

With Singapore-made dramas already making forays into other parts of Asia, it was only a matter a time before a dedicated news channel would be set up. In March 1999, the English-language Channel NewsAsia (CNA) was launched, initially for a Singapore-only audience. Its international feed began in September 2000. Then Minister for Information and the Arts George Yeo hailed the launch at a time of economic crisis as a “bold move”. He said that CNA would “help meet a growing demand for news in real-time presented from an Asian viewpoint” and that it would “supplement other international news channels and help make Singapore a business centre and a media hub”.22 Today, CNA, which broadcasts primarily out of Singapore, has correspondents in over a dozen Asian cities and major Western capitals and is watched in over 25 territories across the world.23

In June 1999, TCS’ parent holding company, Singapore International Media, underwent a name change to Media Corporation of Singapore (MCS) or Mediacorp Singapore. This paved the way for a subsequent restructuring of Mediacorp just three weeks later. Seven strategic business units were formed for TV channel management with TCS (running Channels 5, 8 and taking on sports programmes from STV12), public service broadcasting (STV12), radio (Mediacorp Radio), TV film production and distribution (Mediacorp Studios and Raintree Pictures), news and current affairs (Mediacorp News), print (Mediacorp Press) and Multimedia (Mediacorp Interactive). In 2001, TCS was renamed Mediacorp TV and STV12 took on the name Mediacorp TV12.24

Media Wars

These name changes were far from just cosmetic; they were to prepare Mediacorp’s business units for the onslaught of competition to come. Then Minister for Information and the Arts Lee Yock Suan (who succeeded George Yeo as minister in 1999) hinted at the possibility in Parliament in March 2000 and by June, announced a measured Singapore-style approach to media liberalisation. Lee said the loosening up would be done gradually, through the introduction of “controlled competition”.25

What this meant was that Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) would be issued broadcast licences for radio and TV, while Mediacorp would be allowed to operate a newspaper. The announcement sparked off a frenzy within both local media giants. Almost overnight, in a bid to outdo each other, staff members were poached, new newsrooms were built, haggling over content licensing deals began and advertising rates were drastically slashed. The fallout was brutal. By the end of four years, the two companies had racked up losses totalling over S$200 million. By September 2004, they declared a truce, and in fact, a merger. Mediacorp CEO, Ernest Wong, summed it up by saying: “We are married.” The government denied it had directed the companies to do so, saying the commercial entities were answerable to their shareholders.26

It was not all doom and gloom however. The four years of controlled competition spurred both companies to think more strategically and produce better content. Mediacorp pre-emptively locked SPH out from bidding for popular Hollywood shows by aggressively securing the rights for eight of the 10 top American series for its TV station SPH MediaWorks – the remaining two, Sex and the City and Will and Grace would not have been allowed on air due to censorship regulations.27 MediaWorks created the hit sitcom, Ah Girl (2001–03), and produced excellent nightly newscasts containing in-depth analyses of local developments and polished TV graphics. Unfortunately for SPH, these innovations and the many Chinese and Chinese-dubbed dramas it acquired were not sufficient to persuade more viewers to switch the channel in its favour.

In the early 2000s, Mediacorp found a new cash cow when it bought the rights and adapted Western TV game shows such as Who Wants to be a Millionaire, The Weakest Link and The Wheel of Fortune Singapore, for local audiences. These proved so popular that Channel 5 increased the proportion of hours of game shows it aired from 8 to 20 percent over four months in 2002.28

Going Global

In a new development, Mediacorp started selling its own home-grown programme formats to other broadcasters to adapt. In 2013, it closed a deal with the Thai Public Broadcasting Service to license Mediacorp’s The Arena debate show for young people in the Thai market. The broadcaster is also finding growth in lucrative markets abroad, such as Vietnam, where it sold nearly 1,500 hours of Mandarin content to distributor, Goldia One Vision; THVL 1 and THVL 2 channels and Today TV. In the same year, Vasantham channel’s most popular police drama series, Vettai, was acquired by Malaysian terrestrial channel, ntv7. Other major buyers of Mediacorp productions include broadcasters in Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Philippines and Taiwan. Such deals are an important source of revenue for the home-grown broadcaster to expand in an increasingly fragmented and globalised market.29

The Little Nyonya topped ratings on Malaysia’s ntv7 and Astro’s AEC cable channel, even surpassing viewership for popular Hong Kong dramas in Malaysia. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.

The Little Nyonya topped ratings on Malaysia’s ntv7 and Astro’s AEC cable channel, even surpassing viewership for popular Hong Kong dramas in Malaysia. Courtesy of Mediacorp Pte Ltd.Singapore has also become home to a host of foreign broadcasters, including AXN, BBC, CNBC Asia, Discovery Asia, HBO Asia, MTV Asia, Nickelodeon and Walt Disney Television, in no small part due to the efforts of MDA. The state broadcasting regulator and promoter has gone beyond encouraging media companies to provide services for hire to providing funding and promoting Singapore-made content.30

In recent years, many foreign broadcasters have set up regional sales and distribution offices in Singapore. In some cases, they also commission content to be made by local production houses. For example, Singapore-based Infinite Studios worked with HBO Asia, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and Great Western Entertainment to co-produce HBO Asia’s first original series, Serangoon Road (2013), a 10-episode detective series set in 1960s Singapore. HBO Asia has since inked a partnership with MDA to grow and develop drama production in the local media industry.

Several times a year, MDA leads delegations of local media companies to major industry marketplaces such as Cannes and Hong Kong to promote the sale and distribution of Singapore-made content. It also provides grant schemes to support local production houses, from pitch and production to promotion of their content.31 These efforts have helped homegrown media producers and directors win international awards and have their works seen in over 70 countries around the world, putting Singapore on the world map for original English-language TV and animation content from Asia.

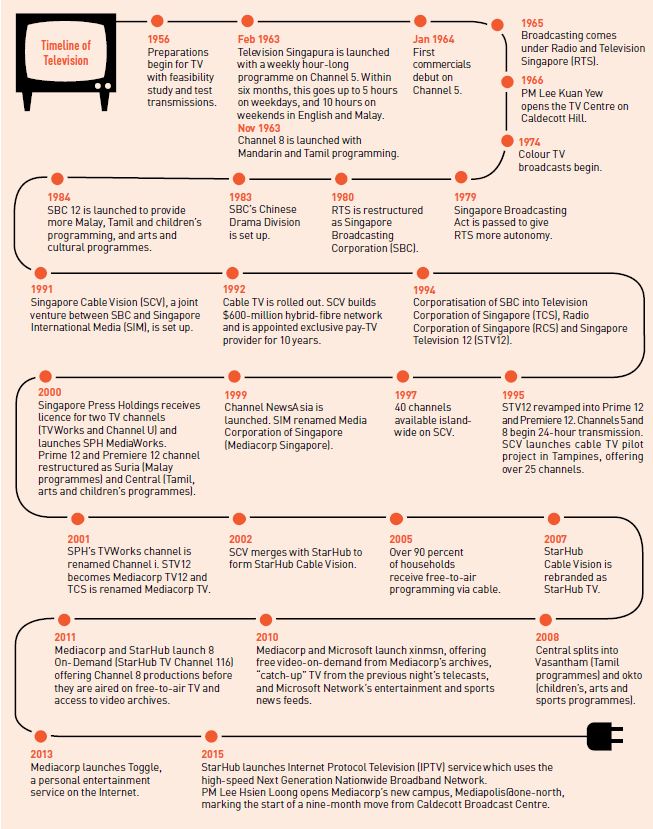

Timeline of Television

A lawyer by training, Lau Joon-Nie spent 15 years in broadcast television as a reporter, interactive producer, current affairs producer and editor at Mediacorp’s Channel News Asia and its predecessors SBC News and TCS News. She now heads Newsplex Asia, a convergent training newsroom and media lab at the Nanyang Technological University.

A lawyer by training, Lau Joon-Nie spent 15 years in broadcast television as a reporter, interactive producer, current affairs producer and editor at Mediacorp’s Channel News Asia and its predecessors SBC News and TCS News. She now heads Newsplex Asia, a convergent training newsroom and media lab at the Nanyang Technological University.

NOTES

-

All six seasons of Growing Up are available for viewing on Mediacorp’s online Toggle platform. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014, December 23). Singapore’s first television station. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Programme for TV pilot service. (1963, February 14). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Koh, T., et al. (Eds). (2006). Singapore: The encyclopedia (p. 554). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57003 SIN) ↩

-

Lent, J.A. (Ed.). (1978). Broadcasting in Asia and the Pacific: A continental survey of radio and television (p. 161). Philadelphia: Temple University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 384.5095 BRO) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2015, March). Singapore Broadcasting Corporation is established. Retrieved from HistorySG. ↩

-

Mahbubani, G. (1980, March 26). High hopes and old problems for the new station. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1979, December 11). Third Reading of the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation Bill (Vol. 39, col. 535). Singapore: [s.n]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Ramesh, S. (2012, March 2). Public Service Broadcast Review panel’s ideas to improve programmes. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩

-

Channel NewsAsia. (2012, July 9). MDA gave S$470m in support of public service broadcasting over past 5 years. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website; Ministry of Communications and Information. (2014, November 20). Public Service Broadcast (PSB) programmes. Retrieved from Ministry of Communications and Information website. Government funding for PSB programmes rose 35 percent from S$470 million (FY2007–11) to S$630 million (FY2012–16). This supports over 4,000 hours of programmes each year, about half of which are produced locally and the rest (e.g. educational, arts and cultural programmes) acquired from abroad.] ↩

-

Generally, only foreign embassies, financial institutions, hotels and selected educational institutions are allowed to install satellite dishes or subscribe to satellite TV operators. See Satellite dishes OK for hotels, some schools. (2003, June 21). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (1992). First subscription television channel written by Nureza Ahmad. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Ang, P.H. (2007). Singapore media (p. 17). [Unpublished manuscript]. Retrieved from Nanyang Technological University wesbite. ↩

-

Keshishoglou, J., & Aquilia, P. (2005). Electronic broadcast media in Singapore and the region (p. 82). Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre: Nanyang Technological University; Australia: Thomson Learning. (Call no.: RSING q384.0959 KES) ↩

-

Ang, 2007, p. 17. ↩

-

Chan, B. (2013, May 30). 50 years of TV. The Straits Times, pp. 6–7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2015). Activities/News. Retrieved from Mediacorp website. ↩

-

Tan, K.P. (2008). Cinema and television in Singapore: Resistance in one dimension (p. 126). Leiden; Boston: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 791.43095957 TAN) ↩

-

Ministry of Information and the Arts. (1999. March 1). Speech by George Yeo, Minister for Information and the Arts and 2nd Minister For Trade & Industry, at the launch of Channel NewsAsia on 1st March, 1999 at 9.00am [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Channel NewsAsia. (n.d.). About us: Our coverage. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩

-

Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2011). Mediacorp interactive history. Retrieved from Mediacorp website. ↩

-

Chua, L.H. (2000, March 11). Media restructuring: The million-$ question. The Straits Times, p. 79; Chua, M.H. (2000, June 6). SPH offered broadcast licences, Mediacorp a print licence. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chia, S.-A. (2004, October 20). No going back on opening up media market. The Straits Times, p. 7; Chua, M.H. (2004, September 19). Media marriage: Happily ever after? The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore Press Holdings. (2004, September 17). Mediacorp and Singapore Press Holdings merge their TV and free newspaper operations [Press release]. Retrieved from SPH website. ↩

-

Osborne, M. (2001, May 21–27). Mediacorp fights for dominance in TV arena. Variety, Special Report, p. 41. Retrieved from ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Lim, T. (2004). Let the contests begin! ‘Singapore slings’ into action: Singapore in the global television format business (p. 114). In A. Moran & M. Keane. (Eds.), Television across Asia. London and New York: Routledge Curzon. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2013, March 20). Mediacorp sold The Arena programme format to Thai PBS; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2013, July 15). Mediacorp’s content sales in Vietnam hit an all-time high; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2013, May 15). Vettai acquired by Malaysian channel ntv7; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2009, September 10). A Mediacorp time-belt on the Philippines’ TV5 – A total of 520 hours of content to be scheduled in the first year!; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2012, October 18). Mediacorp sold more than 100 hours of content to TVB & 8TV; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2012, November 22). Mediacorp’s international channel 8i turns one on Indovision!; Mediacorp Pte Ltd. (2013, January 3). Mediacorp sold 61 hours of variety programmes to Asia Travel TV in Taiwan! All press releases retrieved from Mediacorp website. ↩

-

Media Development Authority. (2014). Broadcast & public service broadcast. Retrieved from MDA website. ↩

-

Media Development Authority. (2015, December 2). HBO Asia works with the Media Development Authority of Singapore to develop local drama production capabilities [Press release]; Media Development Authority. (2014, October 9). Fact Sheet – Singapore makes strong showing at MIPCOM with line-up of over 530 hours of Asian and original TV and animation content [Press release]; Media Development Authority. (2014). Grants & schemes. Retrieved from MDA website. ↩