Bahau: A Utopia That Went Awry

The resettlement of Eurasian and Chinese Catholics in the jungles of Malaysia during World War II has been largely forgotten. Fiona Hodgkins chronicles its painful history.

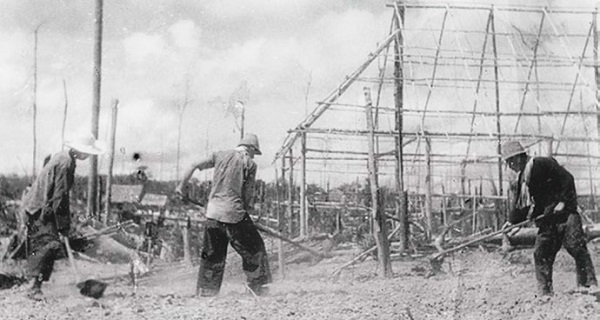

Bahau settlers at work on their land (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.

Bahau settlers at work on their land (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.The story of Bahau has long been a footnote in the larger story of World War II in Singapore, preserved mainly as an anecdotal record among families who have had the misfortune of being part of this experiment.

When I first started looking for information on Bahau in 2008, the only publicly available records in Singapore were found at the Memories at Old Ford Factory1 and the World War II galleries of the Eurasian Association2 in Ceylon Road. Unfortunately, as the association is seldom visited by non-Eurasian visitors, its Bahau exhibition – which opened in 2006 – documents the memory of a place for people who are already familiar with the story.

It’s probably true to say that many readers of this publication, however much they know about the story of World War II in Singapore, will likely not have heard of Bahau…

Where is Bahau?

Bahau3 is a town in the state of Negeri Sembilan in Malaysia. Today it is a somewhat nondescript semi-industrial town surrounded by plantations, and is not particularly known to most Malaysians. Indeed, since publicity surrounding the publication of my book4 about the settlement of Bahau emerged in 2014, various people have come forward to speak to me at public events – interested not so much in the historical angle of my research, but in the fact that the tiny, obscure town they came from was actually interesting enough to be talked about.

In the 1940s, Bahau did not have the industry that it thrives on today, but was known simply as a small town along the Gemas train line travelling north-east through the Malay Peninsula. Founded in a slightly elevated position and surrounded by jungle, it was this off-the-beaten-track location that was chosen as a resettlement area for a wartime civilian population from Singapore. Bahau, which was set up in 1943 by the Japanese army in Singapore, with the express approval of the local Catholic Church, was home to around 3,000 mainly Singaporean Catholics for nearly two years.

Although the settlement was located about five miles from the town centre of Bahau, it is still commonly referred to as Bahau. Many residents of Bahau town are blissfully unaware of the existence of this wartime camp at their doorstep and what took place there.

My Interest in Bahau

So what led me in 2008 to find out more about this forgotten settlement in Malaysia?

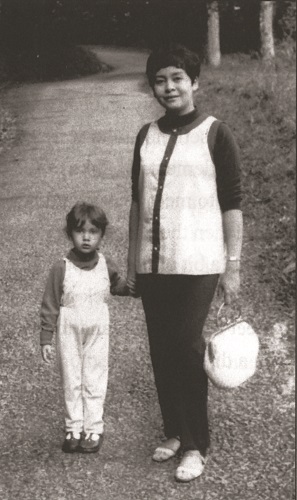

I was born in Japan in 1966 to a British father and Eurasian5 mother (originally from Malacca in Malaysia), and brought up as an expatriate child in Japan, Europe, Singapore and Malaysia – places where my father’s work took him. It was only when my mother, Mary Alethea de Souza, died in England in 2004 that I sought to find out about my heritage, both for my own sake and that of my children, as I did not want them to grow up not knowing the background of their maternal grandmother. When I returned to Singapore in 2008, I wanted to revisit old memories from when I had lived here as a child in the 1970s and 80s, to satisfy my thirst for the past and, more importantly, to find out more about my family history.

The author, Fiona Hodgkins, was born in Japan in 1966. Her father is British and mother Eurasian. This is a photo of Fiona and her mother taken in Japan, circa 1970. Courtesy of Fiona Hodgkins.

The author, Fiona Hodgkins, was born in Japan in 1966. Her father is British and mother Eurasian. This is a photo of Fiona and her mother taken in Japan, circa 1970. Courtesy of Fiona Hodgkins.Having visited all the usual historical sights in Singapore, I finally made the trek to the Eurasian Association at Ceylon Road. This was where I learnt more about Bahau. Until then, my only knowledge of Bahau was through the childhood stories my mum told of the time when she and her family lived in the jungle and when wooden huts used to collapse whenever elephants needed to scratch their backs against the bristly walls of these makeshift dwellings. I thought it was a quaint fairy tale: never did I imagine that it was a real story.

A chance meeting at the Eurasian Association with the education officer there led to an introduction to the people who had set up its war galleries. My hunger to find out about my own roots aligned with their quest for more information about Bahau, and that is how my research project was born.

Historically, the Eurasian community in Singapore has never exceeded more than five percent of its total population. The community has always been a close-knit one with many shared experiences and plenty of inter-marriages within the group.

So, the story of Bahau is also the story of the Eurasian community in Singapore; there is not a single Eurasian family from living memory who either did not live in Bahau or had friends or relatives or forebears who did. As the story of Bahau was passed down informally from one generation to the next, it became preserved within the community and never gained wider coverage. Approaching the narrative from the outside as such, it soon dawned on me that the Bahau story was much bigger than this, and that it actually had resonance for anyone who is Singaporean.

Wartime Singapore

The hardships and deprivation caused by the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45) has already been widely documented. What I wish to focus on specifically are its effects on the Catholic community in Singapore.

Before the war, there were a number of Catholic religious orders here, including the De La Salle (or Christian) brothers and the Holy Infant Jesus nuns, whose primary task was to set up schools. After Singapore fell to the Japanese in 1942, these missionary teachers were forced to teach within the confines of the rules and regulations set by the Japanese curriculum. The fact that many of the brothers and nuns were Europeans – usually Irish brothers and French sisters – made them figures of suspicion among the Japanese authorities.

This, coupled with the general hardships of the Occupation years – including chronic food shortages, lack of healthcare and indiscriminate rounding up of people for questioning – made the idea of an alternative life outside of Singapore appealing to the Catholic community here. Their saviour was a Japanese official by the name of Mamoru Shinozaki,6 who sought to protect various communities in Singapore who were most at risk from the Kempeitai (Japanese secret police). He had earlier helped the Chinese by setting up a settlement in Endau,7 in nearby Johor, and now turned his attention to the Eurasian community.

Shinozaki gained an ally in the Catholic Bishop of Singapore, Adrien Devals,8 who championed the idea of a self-sufficient settlement outside of Singapore to protect Catholics, both lay and religious, from suppression by the Japanese. Bishop Devals and Shinozaki managed to convince the Japanese authorities that if large numbers of people were moved out of Singapore, there would be fewer mouths to feed and much less pressure on the local infrastructure. Additionally, whatever surplus crops the people in this overseas settlement produced, could be sent back to Singapore.

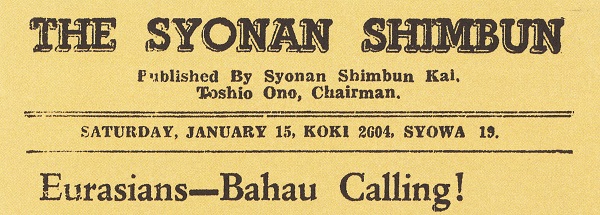

An announcement in the 15 January 1944 edition of The Syonan Shimbun exhorting the Eurasian community to apply for the Bahau settlement scheme, which “all Eurasians who are fit and strong enough to go on the land should avail themselves of enthusiastically”. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An announcement in the 15 January 1944 edition of The Syonan Shimbun exhorting the Eurasian community to apply for the Bahau settlement scheme, which “all Eurasians who are fit and strong enough to go on the land should avail themselves of enthusiastically”. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Now, while the majority of Eurasians in Singapore were Catholic, there were small numbers of Chinese Catholics too, especially among the Peranakan community – which is likely why their role in Bahau has been largely overlooked by many. In fact, over 1,000 Chinese Catholics, nearly as many as Eurasians, settled in Bahau. The Chinese Catholics came mainly from the parish of Holy Innocents in the Serangoon area, Church of Saints Peter and Paul on Queen Street, and St Theresa’s Church on Kampong Bahru Road. Many Catholic Chinese were eager to move to Bahau as the memories of the horrific Sook Ching massacres were still fresh in their minds.9

In addition to these Catholics, a small group of Protestant European families and neutrals from countries like Switzerland, Denmark, Romania and Russia chose to go to Bahau too, thinking that they would be safer there under the care of the Catholic Church than left to the mercy of the Japanese authorities in Singapore.

Life in Bahau

It was in late December 1943 that the first settlers from Singapore – including Bishop Devals – left for Bahau with whatever belongings they could carry: meeting first at the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd on Queen Street, then travelling by overnight train to Gemas; followed by a local train to Bahau town and finally walking the last five miles to the site chosen as the settlement.

Stretching over an area of some 40 square miles, the land chosen for the settlement had previously been cleared and rejected by the Japanese for use as an airfield and then by the Chinese who chose to settle in Endau instead. Both groups had allegedly rejected the site because of fears of contracting malaria. The fact that the Catholics accepted the offer to resettle in Bahau reflected the sheer desperation of their situation at the time.

Given its inauspicious start, it’s not surprising that the site did not turn out to be the bucolic paradise that the Catholics had been promised. This was made worse by the fact that what had originally started out as an “optional” resettlement programme seemed more like forced internment once the people arrived there. The Japanese name for the camp, Fuji-Go, which means “beautiful village”, was ironic given the fact that an estimated 500 settlers died over an 18-month period between 1944 and 1945.

The first settlers, mainly young, single men, lived communally in four sheds constructed by the authorities. They were first assigned to clear the land still overgrown with primary jungle, build a rudimentary road from the train station to the camp and set up basic infrastructure before the families started to arrive. Each family was allocated 3 acres of land to grow crops and build their own home using whatever they could find from the jungle – basically split timber and palm fronds – although some of the more fortunate families could afford to pay local contractors to build sturdier structures.

The first settlers to Bahau – mainly young, single men – had to clear the land, build a rudimentary road from the train station to the camp and set up basic infrastructure before the families started to arrive (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.

The first settlers to Bahau – mainly young, single men – had to clear the land, build a rudimentary road from the train station to the camp and set up basic infrastructure before the families started to arrive (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.Then began the difficult task of survival. Those who toiled hard in their allocated land parcels never went hungry with bountiful harvests of vegetables such as tapioca, kangkong (water convolvulus) and bangkwang (Chinese turnip). But although they might not have gone hungry, their diets certainly lacked essential nutrients; some resorted to eating jungle animals (such as snails and iguanas) or killing goats, which had been kept as family pets, for protein. The harsh living conditions and poor diets made the settlers vulnerable to malaria and a host of tropical ailments and diseases. Not surprisingly, the death toll was high.

The morning roll call was a daily ritual at Bahau camp [Japanese propaganda photo]. Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.

The morning roll call was a daily ritual at Bahau camp [Japanese propaganda photo]. Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.Still, some settlers remember happy days, a testimony of the human ability to see the positive in the face of adversity. Gwen Lange née Perry, who was then a teenager, recalls enjoying greater freedom than she would have been permitted in Singapore, including being allowed to attend monthly parties held in a neighbour’s house in the settlement. People would walk 45 minutes in pitch dark to get to the house, where some would bring musical instruments to play and homemade rice whisky would be shared in an atmosphere of conviviality.

However, in spite of a measure of freedom within the settlement itself, there was no escaping from Bahau; the inhabitants were hemmed in by the surrounding dense jungle and the only road access was guarded round the clock by sentries. Only those with exit permits for special reasons were allowed temporary release.

While the true conditions of the settlement were hidden to the outside world by the Japanese authorities who made regular visits and censored information that went out, the settlers managed to come up with ingenious ways to keep their loved ones in Singapore informed about what Bahau was really like, and warn them from electing to resettle there. For example, one settler had arranged with his loved ones to write the letters in ink if the situation at Bahau was favourable and in pencil if it was not. Another used the phrase “singing the prisoners’ love song” in the letter to mean everything was well at the camp, but if the letter said people were “not singing the prisoners’ love song”, then things were not looking good.

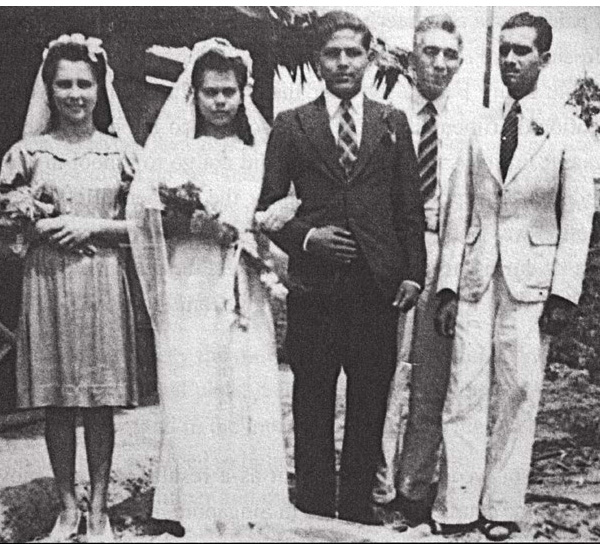

But it was not all gloom and doom in Bahau. Budding romances that had begun in Singapore blossomed in the settlement and resulted in marriages. There were also some who were fortunate to meet their future spouses at the settlement.

Wedding photo of Luke de Souza and Flo Chopard. [From the left]: Gwen Perry, Flo Chopard, Luke de Souza, Bill Hutchinson and an unknown person. In spite of the difficult circumstances in Bahau, several weddings were celebrated there. Courtesy of the family of Luke and Flo de Souza.

Wedding photo of Luke de Souza and Flo Chopard. [From the left]: Gwen Perry, Flo Chopard, Luke de Souza, Bill Hutchinson and an unknown person. In spite of the difficult circumstances in Bahau, several weddings were celebrated there. Courtesy of the family of Luke and Flo de Souza.The Legacy of Bahau

Bahau was finally liberated on 3 September 1945, a few weeks after the official end of the war in Southeast Asia, when a team from Force 13610 followed up on leads about the possible existence of a civilian camp in the jungles of Bahau. For the settlers, this was a heaven-sent escape from the brief period when communist guerrillas in Malaya replaced the departing Japanese garrison in Bahau. Many remember the short communist takeover as the most frightening part of their stay in the settlement. Following the arrival of Force 136, it took another six weeks to organise the repatriation of the settlers. It was only in mid-October 1945 that the last of the settlers were evacuated.

The Japanese Occupation in Singapore left an indelible mark on everyone who survived the period: many lived in constant fear, lost loved ones, and had to make do with much less than before the war. The Bahau experiment that went horribly wrong was very much a variation of this theme.

My extended family members in Bahau were some of the lucky ones. In one house was my mother who lived with her parents, three sisters and an uncle. They were later joined by her maternal grandparents and three cousins. In a second house nearby lived my mother’s paternal grandparents, two uncles and an aunt and their spouses. Of this large group, only one of my great grandmothers, who already had a pre-existing condition (of course exacerbated by the ravages of jungle life), died there. We are fortunate in that we know where she is buried: in the cemetery in Seremban. Many families, whose loved ones may have initially been buried in the Bahau settlement, do not know where their remains rest now.

My grandfather Herman de Souza (Jnr), despite having had a good relationship with Shinozaki, felt so strongly about the Japanese that he refused to visit their country when my parents lived there from 1965 to 1972 because of my father’s job. Thankfully, my grandmother, who lost a sister and brother-in-law in the war and having suffered terribly in Bahau, was able to put family above her animosity towards the Japanese; she visited Japan on a number of occasions, including for my birth.

Many people who lived in Bahau have tried to put the experience behind them, or indeed to bury the memory altogether by not talking about it to their children at all. As a result, the story has become largely forgotten over the years; only those who were impacted by the experience recall the unspoken pain.

I feel very privileged to have met so many survivors and have had access to so many previously unpublished documents, making it possible for me to unearth the story of Bahau and record it for others.

THE BISHOP WHO LED BY EXAMPLE

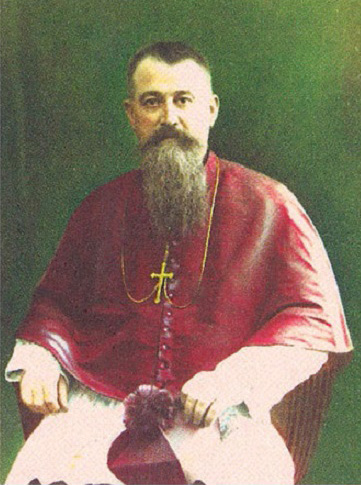

Bishop Adrien Devals was a French priest who became the leader of the Catholics in Singapore from the late 1930s. He led the first group of settlers to Bahau and tragically died there. All rights reserved, Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An Illustrated History (1819–Today). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

Bishop Adrien Devals was a French priest who became the leader of the Catholics in Singapore from the late 1930s. He led the first group of settlers to Bahau and tragically died there. All rights reserved, Pilon, M., & Weiler, D. (2011). The French in Singapore: An Illustrated History (1819–Today). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

Bishop Adrien Devals, who led the first group of settlers in Bahau and tragically died there, should be more widely credited for his leadership there under adverse circumstances. Although Bahau failed as an experiment, it does not detract from Devals’ altruistic reasons for approving the resettlement plan.

Born in 1882 in Quins, France, Devals entered the seminary of the Société des Missions étrangères de Paris (MEP) in 1900 and was ordained a priest six years later. He arrived in Penang in September 1906 where he was initially the assistant at the Church of the Assumption, and later its parish priest. In 1934, he was appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Malacca, which included Singapore, and served in that role until his death in 1945.

When Mamoru Shinozaki offered Bahau to the Catholics as a settlement, Devals saw it as a way to protect both his flock and the religious communities for whom he was responsible. Although he was already 60 years old, Devals led by example and moved to Bahau too, among the first convoy of settlers who left Singapore in December 1943. The priests, brothers and nuns, including the bishop, lived in the same conditions as everyone else in Bahau.

Devals was in charge of the day-to-day running of the settlement and took charge from the start, assigning roles to the settlers, such as setting up anti-malarial teams and liaising with the Japanese authorities. He did not accord himself special privileges, sleeping in the same communal lodgings with the others and eating the same food. A few months later, as people began to move into the houses they had built, so too did the Bishop. He lived in a spartan hut that afforded him a bit of peace and quiet time for prayer and contemplation.

In the early days in Bahau, Devals relied heavily on the religious brothers for leadership and organisation as well as a core of lay people whom he knew and trusted. But as time went on and conditions in the settlement did not improve, Devals struggled to provide effective governance in the face of growing dissent from members of the laity. Still, he maintained his position in his belief of the motto “Non mea voluntas sed Tua” – Latin for “Not my will but Yours”, from the gospel of St Luke.

Unfortunately, Devals’ health was failing – the physical hardships of Bahau, including malaria, took their toll. To make matters worse, he suffered from diabetes, and a bad scratch on his right foot sustained from farming eventually became infected and turned gangrenous, requiring the amputation of his leg. Sadly, the operation was not enough to save Devals and he died in a hospital in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, on 17 January 1945, having spent just over a year in Bahau.

Devals’ body was taken to Singapore where “a requiem mass was held at the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, attended by all the top ranking Japanese officers… almost a state funeral” performed with dignity and respect from Singaporeans and Japanese.11 Shinozaki described him as a “noble and fearless man” and said that at the funeral he “kissed the corner of the coffin” because he had “always held him in respect as a God-fearing man”.12

MAMORU SHINOZAKI: THE JAPANESE SCHINDLER

Mamoru Shinozaki was instrumental in saving many lives in Singapore immediately after the surrender of the British on 15 February 1942. All rights reserved, Shinozaki, M. (2011). Syonan, My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions.

Mamoru Shinozaki was instrumental in saving many lives in Singapore immediately after the surrender of the British on 15 February 1942. All rights reserved, Shinozaki, M. (2011). Syonan, My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions.

Mamoru Shinozaki, often described as the “Japanese Schindler”, was instrumental in saving many lives in Singapore immediately after the surrender of the British on 15 February 1942.

Shinozaki worked with the Catholic Bishop in Singapore, Adrien Devals, to gather a number of Catholics from the so-called “clean-up operation” assembly points and take them to a church where they were subsequently released.13 He also issued between 20,000 and 30,000 “protection cards” to people. This was a card with a stamp saying “Special Foreign Affairs Officer of Defence Headquarters”; each card stating that the bearer of the pass was a “good” citizen and requesting Japanese soldiers to “please look after him and protect him”. According to Shinozaki, these cards were issued to “everyone asking for them” and he “gave hundreds to community leaders to distribute”. He made no attempt to find out whether the cards “went to communists or anti-Japanese elements or bad hats.”14 He was just intent on saving lives.

Shinozaki helped set up the settlement of Endau, in nearby Johor state, for the Chinese, then three months later, Bahau for Catholics. He visited both settlements regularly and many settlers in Bahau have fond memories of him. However, in spite of the good Shinozaki did and the high regard in which he was held by many, he was also viewed with a degree of suspicion by some. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the British arrested him and charged him with espionage together with other Japanese officials (he had been similarly charged with espionage by the British before the war; see Note 6).

Shinozaki was held briefly at the British Field Security Force headquarters at Balmoral Road in Singapore until some Bahau residents, along with other civilians, petitioned the British and secured his release. Shinozaki subsequently worked for the British army as an interpreter and served as a key witness, providing evidence for the war crimes trials held in Singapore against the Japanese soldiers involved in Operation Sook Ching.

My grandfather, Herman de Souza (Jnr), who worked with Shinozaki in the Education Department during the Occupation and later in Bahau, recalled what Shinozaki said to him in 1942: “I was in the diplomatic service of the Japanese, I was trained in Germany, and I had great ambitions. I was going to rise in the consulate world. But when the British interned me in this place, I had time to think, and I have now only one ambition. … My ambition now is to do good to people. Doesn’t matter who they are.”15

After the war, a letter published in The Straits Times on 19 August 1946 made the case for allowing Shinozaki to stay in Singapore. The writer of the letter was my great-uncle, P. F. (Pat) de Souza, a lawyer who personally knew Shinozaki through his practice in Singapore before the war, and later during his internment in Bahau. He closed his letter by saying: “I do feel that Shinozaki’s public spiritedness and achievements – at a time when we who were there were subjected to all kinds of degradations – characterise him as a great humanitarian and a great gentleman.”16

Fiona Hodgkins (right), a history graduate whose professional life has revolved around history and education, spent 14 years in Singapore. Her research into Bahau arose from a personal quest and a passion for social history. From Syonan to Fuji-Go (2014), which chronicles her research, is her first book. Fiona is pictured here with Gwen Perry, a survivor of the Bahau settlement.

Fiona Hodgkins (right), a history graduate whose professional life has revolved around history and education, spent 14 years in Singapore. Her research into Bahau arose from a personal quest and a passion for social history. From Syonan to Fuji-Go (2014), which chronicles her research, is her first book. Fiona is pictured here with Gwen Perry, a survivor of the Bahau settlement.

REFERENCES

Books

Hodgkins, F. (2014). From Syonan to Fuji-Go: The story of the Catholic settlement in Bahau in WWII Malaya. Singapore: Select Publishing. Call no.: RSING 307.212095957 HOD

La Brooy, M. (1987). Where is thy victory? [S.l. : s.n.,]. Call no.: RSING 940.5481 LAB-[WAR]

O’Donovan, P. (2008). Jungles are never neutral: Wartime in Bahau: An extraordinary story of exile and survival: The diaries of Brother O’Donovan fsc. Ipoh, Malaysia: Media Masters Publishing. Call no.: RSING 940.5308827178 ODO-[WAR] [previously published as: Under the Hinomaru, Ipoh: The La Salle Brothers, 1978]

Oehlers, J. (2011). That’s how it goes: The way of the 90-year life journey of a Singapore Eurasian. Singapore: Select Pub. Call no.: RSING 617.6092 OEH

Shinozaki, M. (1975). Syonan, my story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Singapore: Asia Pacific Press. Call no.: RCLOS 940.548252 SHI

Van Cuylenburg, J. B. (1982). Singapore: Through sunshine and shadow. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. Call no.: RSING 959.57 VAN-[HIS]

Wijeysingha. E., & Nicolas, R. (2006). Going forth…: The Catholic Church in Singapore 1819–2004. Singapore: Nicholas Chia. Call no.: RSING 282.5957 WIJ-[SRN]

Newspapers

The Straits Times

The Syonan Shimbun

The Syonan Times

Unpublished sources

Heine, Major K.R.R. Royal Engineers. (1945). “Operation Galvanic Slate”. From the private papers of G. Tack. Imperial War Museum, London.

Meissonnier, P, (1947). Memories of Bahau: December 1943– October 1945. [Translated by René Nicholas. Originally published as Un évêque missionnaire, chef du STO en Malaise Missionnaires d’Asie, no 29-30-31].

Oral history interviews (available at the National Archives of Singapore) Bogaars, George Edwin (1983) (Accession nos.: 000032, 000379)

De Souza (Jnr), Herman Marie (1985) (Accession no.: 000592)

Marcus, Philip Carlyle (1982) (Accession no.: 000183)

Woodford, Esme (2007) (Accession no.: 003267)

For a full list of references behind the research, see Hodgkins, F. (2014). From Syonan to Fuji-Go: The story of the Catholic settlement in Bahau in WWII Malaya. Singapore: Select Publishing. Call no.: RSING 307.212095957 HOD

NOTES

-

Museum commemorating the site of the British surrender of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. Located on Upper Bukit Timah Road, it is currently closed for renovations and will open in the first quarter of 2017. ↩

-

Established in Singapore in 1919, the Eurasian Association is one of the earliest community associations set up to look after the interests of Eurasians. ↩

-

Bahau is the principal town of the Jempol district. The name Bahau is believed to have derived from a Chinese phrase, 馬口, literally translated as “Horse’s mouth”. ↩

-

Hodgkins, F. (2014). From Syonan to Fuji-Go: The story of the Catholic settlement in Bahau in WWII Malaya. Singapore: Select Publishing. Call no.: RSING 307.212095957 HOD ↩

-

The term Eurasian refers to a person of mixed European-Asian ancestry. Historically, it refers to anyone who descended from the first European-Asian unions in the region between the 16th and 18th centuries. Most Eurasians in Singapore trace the European part of their ancestry to the Portuguese, Dutch or British. ↩

-

Mamoru Shinozaki had been in Singapore before the war as a press attaché at the Japanese Consulate. Interned by the British for espionage, he was subsequently released by the Japanese when Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. He was then appointed as a senior Japanese official initially with a remit for education and later welfare (see text box above). ↩

-

A small town in Malaysia located on the northern tip of east Johor and the southern tip of Pahang, whose name became synonymous with the Chinese settlement set up in September 1943. ↩

-

Bishop Adrien Devals was a French priest who became the leader of the Catholics in Singapore from the late 1930s (see text box above). ↩

-

Following the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Chinese males between 18 and 50 years of age were ordered to report to designated centres for mass screening. Many of these ethnic Chinese were then rounded up and taken to deserted spots to be summarily executed. This came to be known as Operation Sook Ching (the Chinese term means “purge through cleansing”). It is not known exactly how many people died; the official estimates given by the Japanese is 5,000 but the actual number is believed to be much higher. ↩

-

Force 136 operated in Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia during World War II and was the general cover name for a branch of the British World War II organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). ↩

-

Wijeysingha E., & Nicolas, R. (2006). Going forth…: The Catholic Church in Singapore (p. 140). Singapore. Nicholas Chia. Call no.: RSING 282.5957 WIJ ↩

-

Shinozaki, M. (2011). Syonan, my story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (p. 136). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. Call no.: RSING 959.57023 SHI-[HIS] ↩

-

Tan, B. L. (Interviewer). (1985, August 17). Oral history interview with Herman Marie de Souza. [Transcript of MP3 Recording No. 000592/06/03, p. 28]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

De Souza, P. F. (1946, August 19). Spy and humanitarian. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩