Mem, Don’t Mess with the Cook

European families in colonial Singapore had a retinue of servants – cook, chauffeur, nanny, gardener and houseboy – but this did not guarantee a life of ease, as Janice Loo tells us.

Malay Police Constable no. 623 was on duty at Anson Road on the afternoon of 21 February 1907 when a European lady with a bloodied nose appeared, dragging a Chinaman firmly by his queue. Mrs Muddit had been attacked by her Hainanese cook, Lim Ah Kwi, and she was not about to let him get away.

The next morning, Ah Kwi was brought before the magistrate and charged with using criminal force on his employer. The furious Mrs Muddit alleged that the cook had defied her orders and wanted to do as he pleased with the dinner menu (how dare he!). Indignant at being rebuked, Ah Kwi brandished a knife at his mistress before striking her on the face with a piece of wood.1

Mrs Muddit was far from alone in her troubles for the management of domestic servants was an everyday ordeal for the European wife, or memsahib2 (often truncated as mem), in Singapore and Malaya.

Arrival of the Mems

European women began arriving in larger numbers from 1910 onwards as improvements in living conditions made the prospect of travel and residence in Malaya less daunting. While a fraction of the European female population comprised single women who were engaged in teaching, missionary or medical work, the majority were wives of men in government service and those engaged in private enterprise.3

As homemakers and mothers, mems were crucial to the re-creation of domestic and social life in colonial settings. These women were regarded as a civilising influence on a community that, in the words of E. M. M., writing in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, “consisted almost entirely of men, whose ideas of household management and the running of their homes were in most cases nil”.4 Seen from a larger perspective, the domestic role of European women in the colonies carried a political significance: by upholding the standards of Western domesticity, mems maintained the collective identity and prestige of the ruling elite, thereby reinforcing the divide between the subject races and their colonial masters.5

The availability of domestic help meant that the mem did not so much keep house as oversee its upkeep.6 European families engaged a minimum of three and often more than six servants, comprising a houseboy (“Boy”), a water-carrier (tukang air), a cook (“Cookie”), a syce or chauffeur, a gardener (kebun), a washerman (dhoby) and a nanny (amah) to look after the children.7 These positions were typically held by men, with the exception of the amah.

It was not unusual for European households to have more than a dozen servants: a houseboy (“Boy”), a syce or chauffeur, a gardener (kebun), a washerman (dhoby) and a nanny (amah). Most of these positions were held by men, except the amah. Photo by G. R. Lambert & Co. Fotoalbum Singapur (1890). All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

It was not unusual for European households to have more than a dozen servants: a houseboy (“Boy”), a syce or chauffeur, a gardener (kebun), a washerman (dhoby) and a nanny (amah). Most of these positions were held by men, except the amah. Photo by G. R. Lambert & Co. Fotoalbum Singapur (1890). All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Chinese male immigrants from Hainan dominated the domestic services, forming some 90 percent of servants in European households.8 Nevertheless, there existed a degree of occupational specialisation along racial lines as a British resident in the 1930s notes: “Cookie and Boy are usually Chinese. The Kaboon [sic] is almost invariably a Tamil… the Sais [sic], or chauffeur… is usually a Malay.”9

In the absence of plumbing, gas stoves, electricity and other modern amenities, housework was a primitive and strenuous affair made even more irksome in the sweltering heat. The presence of servants in the home was absolutely essential to the well-being and status of the European community, as one mem pointed out, “doing all the cooking [and by association other chores] involves not only a loss of prestige but loss of looks and health in the long run”.10

(Left) Portrait of a Chinese amah and a European child, early 1900s. Many European children were brought up by their amahs, or nannies, with whom they often shared a lasting bond. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

(Left) Portrait of a Chinese amah and a European child, early 1900s. Many European children were brought up by their amahs, or nannies, with whom they often shared a lasting bond. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Such views created the impression that all mems were idle, having “nothing to do all day except to seek amusement”11 or at best, “only one duty, to have an interview with Cookie once a day”. Yet the management of servants was viewed as a formidable task in itself, judging by the slew of complaints, tips, comments and advice from white women (and men) on the subject. Among the servants, the cook represented the biggest challenge to the mem’s authority – he occupies “the head of the hierarchy… presides in the kitchen, does the marketing, keeps order amongst the servants, and occasionally consults his mistress, the Mem, on matters of policy. He is the household tyrant…”.12

Beware the Servant

“Chinese are excellent domestic servants. They are sober, industrious, methodical, and attentive to their duties”,13 writes J. D. Vaughan in The Manners and Customs of the Chinese in the Straits Settlements (1879). Although the Hainanese were “in every way the men best adapted for domestic service”,14 grievances against their alleged insolence, dishonesty, and the incompetence of cooks and houseboys were regularly aired in the press and other literature.

The hiring process was fraught with uncertainty as employers lacked the means to verify the character and employment history of prospective servants. Written testimonies were often unreliable, as the following account published in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 3 May 1901 illustrates:

“A few days back, a so-called cook offered me his services and on my asking for his testimonials he produced two letters, signed by well known names of former residents, long since dead. One was dated 1883, the second one, 1891… I also asked how long ago he had left his second master; the answer was ‘A few months back’. And each successive lie was uttered with that superb aplomb which is such a distinguishing feature of the latter day Hylam servant. Nor did he show the least chagrin when I quietly tore up before him the two so-called testimonials and gave him the pieces. ‘Better luck next time’, is all he thought about it and, no doubt, he is by now provided with new testimonials, quite as genuine as the old ones.”15

Given the widespread practice of using borrowed, rented or stolen letters of recommendation, employers often had no practical alternative but to take a servant on trial in order to determine his ability. This brought the danger of “introducing into a household an incorrigible thief, who speedily levies toll on his new employer’s possessions and then ‘silently fades away’”. In such a situation, it was virtually impossible to track down the errant servant for householders rarely knew the real names of their cook and houseboy.16 A more insidious nuisance was cheating employers through overcharging, where the cook would regularly add on a few cents to each item in his daily marketing and pocket the difference – “one of those long standing customs of the country it is no longer any good fighting against”.17

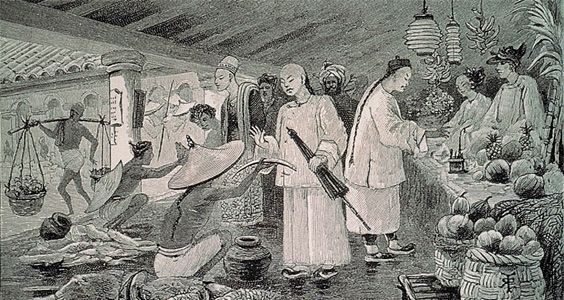

An engraving of a “Town Market” in Singapore. Cooks in colonial households were invariably Chinese males, and going to the market to buy fresh produce was part of their early morning chores. All rights reserved, Liu, G. (1999). A Pictorial History 1819–2000. Singapore: National Heritage Board and Editions Didier Millet.

An engraving of a “Town Market” in Singapore. Cooks in colonial households were invariably Chinese males, and going to the market to buy fresh produce was part of their early morning chores. All rights reserved, Liu, G. (1999). A Pictorial History 1819–2000. Singapore: National Heritage Board and Editions Didier Millet.The crux of the problem, as the European community saw it, lay in the absence of regulation that would enforce discipline and standards as well as check the influence of the Hainanese kongsi, the guild and secret society that controlled the recruitment of servants. Servants were said to have no qualms warning their employers that the kongsi they belonged to would stop others from working for them. “And this is no idle threat”, wrote H. B. Roper in a letter to The Straits Times, “for how many of us have not been obliged to do without servants for days, and were candidly told by those whom we at last managed to secure that they were in mortal fear of being beaten by members of the Kongsees”. In banding together and forming a kongsi, the servants – in a reversal of roles – “have completely succeeded in becoming the masters and dictators of those whom they are supposed to serve”.18

To the European community, the sense that they were at the mercy of a crime syndicate operated by domestic servants is encapsulated in the following letter to the press on 1 May 1901:

“… practically the whole bulk of the male domestic servants in Singapore are Hailams, and that these very men therefore presumably constitute the rank and file of this Secret Society, all who are familiar with the troubles caused by servants – the steady mysterious leakage of jewellery, cash, cutlery, under-linen, and minor domestic articles – the difficulty of getting new servants, under the open institution of a boycott – the constant assumption of false names and the use of borrowed or forged characters – must be well aware that the house-holder is, necessarily, for want of protection, the passive victim of organised Hailam exploitation.”19

Protection for Hapless Employers

The many cases of theft and violence committed by servants fuelled public anxiety such that in July 1886, some 200 European residents, among them the “heads of the leading mercantile firms, leading professional men, and proprietors of all the large hotels and boarding houses, and the Secretaries of the different important Clubs”,20 petitioned the Governor of the Straits Settlements Frederick A. Weld to introduce registration of domestic servants. The appeal was heard and a bill that provided for the appointment of Registrars and a system of registration was drawn up and passed on 30 December 1886.21

Under the Domestic Servants Registration Ordinance, any person employed or seeking employment as a servant may apply – although it was not mandatory– to the Registrar with his name, age, nationality, details of previous employments, together with a $1 fee. Once these requirements were satisfied, the Registrar would record the information in the Register of Servants and issue the applicant an official pocket-register containing his particulars. Householders were encouraged to hire only registered servants and update the servants’ pocket-registers upon commencement or termination of service, and notify the Registrar within three days. Anyone found guilty of supplying false information or impersonation was liable to imprisonment for a period not exceeding three years, or a fine of up to 10 Straits dollars, or both.22

The ordinance came into force on 1 January 1888 and was repealed on 26 October that very year due to fierce resistance from the Hainanese kongsi.23 As a result of the strike mounted by the kongsi, numerous European households “found themselves servantless, and had to break up, and migrate to hotels”.24 The registration proved such a farce that one observer wryly commented that the Registrar “set idle in his office, drawing caricatures on his blotting paper daily and drawing his pay monthly”.25 Employers attributed the failure of the ordinance to its voluntary nature and continued to press for compulsory registration.

In an ironic twist, a letter published in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser from a reader “Ang Mo Kongsi” on 19 April 1905 gave the European community a start. The writer claimed that a police raid on a Hainanese kongsi had unearthed records of all the Europeans in Singapore containing information such as the wages they paid, the amount of work required, whether they beat the servant, what time they returned home at night, if they locked up their possessions and so on – “a sort of complete ‘Registration of Europeans!’”26

In 1912, The Straits Times polled 600 European employers and found near unanimous support for the compulsory registration of servants. While a bill providing for such a measure was passed in 1913, it was never put into operation.27

Mem-in-charge

Most European men were relieved to hand over the management of the household and its trifling frustrations to their wives. For servants long accustomed to lax supervision under a male employer, the arrival of a new mistress, especially one who took to her domestic duties with a certain zealousness, spelled trouble. The mem’s struggle to establish authority was likened to a military campaign, for “however capable she might have been in her house at home, [she] had a stiff battle to fight before she could gather the reins of her new household’s government into her own hands”.28

Housekeeping in Malaya was a whole new ball game. From the outset, it was clear that a rudimentary knowledge of the Malay language was indispensable when communicating with the servants. Until the mem had familiarised herself with the basics of the language as well as housekeeping conditions, one solution was to employ – through recommendations from friends – experienced servants who had previously worked for European families. Although their wages were higher, they were said to be “well worth [the] extra expense, in order to enable the young mistress to feel her feet without loss of dignity”.29

Phrasebooks such as Maye Wood’s Malay for Mems came in handy. Published in 1927 and reprinted well into the 1950s, the book aimed “to place before newcomers, especially women, the most ordinary and necessary words and phrases required in household management”. Written in the imperative, the book features the “most useful” and “most generally required” vocabulary and expressions drawn from the author’s personal experience, such as: “You must follow the mem”, “Go at once”, “I want the car”, “Call the cook”, “Polish the floor well”, and “Wait until master comes”. Peppered with helpful hints to facilitate communication between mistress and servant, Wood notes that “Chinese servants speak Malay very badly, owing to their inability to pronounce certain letters”. For example, they pronounce “R” as “L” such that “roti” (bread) becomes “loti”, and they have difficulty with words beginning with “D” or “S” so that “dapur” (kitchen) becomes “lapur” and “stew” is “setu”. The reader is also apprised of the social norms and power relations attached to language, for example, “Tabeh”, a general greeting that means “Good-day” and “How do you do?”, was “not used by Europeans unless a Native has said [it] first”.30

Bad Cooking, Dirty Food

Aside from their alleged criminal tendencies, another bugbear was the “filthy, and disgusting methods”31 of Chinese servants and the resultant risks to the health of their employers. The common advice was “never to enter or look into a kitchen where food is being prepared by a Chinaman if you would preserve your peace of mind and enjoy your meals”.32 One family discovered that the unappetising odour and taste of the food served by their cook were “due to everything being fried in pig-oil, a horrible black oil beloved of all Chinese servants but which made one shudder only to look at!”33

Another dreaded aspect was the prevalence of venereal diseases among Chinese male servants, giving rise to fears of contagion from consuming food prepared by them. The fear found voice in the following letter from “A Householder” to The Straits Times on 4 August 1891:

“It is no exaggeration to estimate the number of diseased cooks and boys at one in every three, suffering from the effects of their own conduct… and by no means scrupulous and careful, when engaged in cooking and handling the food of delicate ladies and European gentlemen… Let Europeans stop to realise the dangerously unprotected manner in which they are living, and there is little doubt that a strongly indignant appeal will rouse public attention and end in safeguarding the interests of the few white men, who are compelled to live in a tropical climate exposed to many many dangers, not the least of which centres in the servants on whom they must depend for food.”34

MRS KINSEY TO THE RESCUE

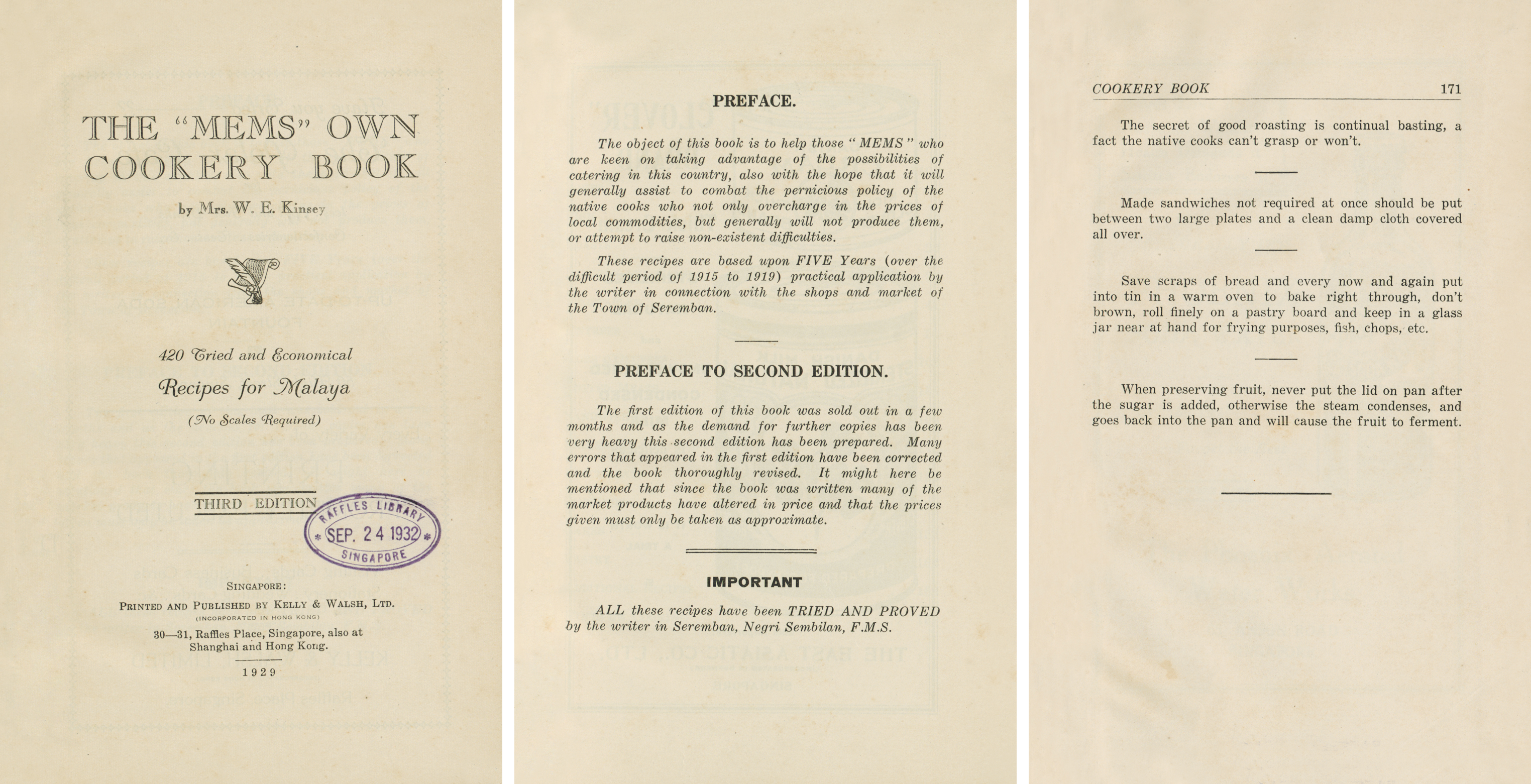

More than a means of self-instruction, the cookbook was used as a manual to train the servants and was instrumental to the mem’s efficient management of the household. This was why The “Mems” Own Cookery Book by Mrs W. E. Kinsey was regarded as a godsend when it was published in 1920. It consisted of “420 tried and economical recipes” with additional information on the market prices of ingredients, the total cost of each dish and the number of servings, thereby helping the mistress to “combat the pernicious policy of the native cooks who not only overcharge for local commodities, but generally will not produce them, or attempt to raise non-existent difficulties”.35

Title page and extracts from The “Mems“ Own Cookery Book. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

Title page and extracts from The “Mems“ Own Cookery Book. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

A review of the book in The Straits Times declared: “With this guide at her elbow… [the new mem] can either prepare herself or instruct ‘cookie’ in a host of dishes which should do a great deal to remove the charge of monotony which is sometimes levelled at food in Malaya”.36

Another popular resource was The Y.W.C.A. International cookery Book of Malaya, which was updated and republished nine times over three decades since it made its debut in 1932. Aside from recipes, the book provides guidance on meal planning, tips on buying local ingredients and other preparatory steps before the actual cooking. Assessing the second edition from the standpoint of an older mem who has long grappled with the question of diet in Malaya, Mrs K. Savage Bailey writes in The Straits Times on 1 August 1935 on the book’s usefulness. She praises, in particular, the section on local market produce with the names for each item given in both Malay and English:

“The young housewife in this country always finds her greatest difficulty is making her cook understand what she wants him to buy in the local market, and as the cook knows that the unfortunate Mem is badly handicapped by lack of knowledge as well as language, he puts on an even [more] stupid air than nature gave him, and goes off to market to buy just what he wants to, and his own price! This article on vegetables will put a stop to that sort of thing, for each vegetable is carefully named, so that there can be no excuse that cookie ‘did not understand Mem’s Malay’.”37

In time to come, it was hoped that the mem, having acquired the necessary knowledge, would find it a breeze to direct the running of the household “with the calm assurance of one who really knows what she is talking about”.38

The mem’s civilising mission included the training of servants in modern concepts of hygiene and nutrition. Grouses about the monotony of the European diet in Malaya and the dearth of cookery skills among Chinese cooks provided further justification for mem’s intervention. One mem laments in an article – expressing condescension of the Chinese cook while bemoaning the white woman’s burden:

“Why do we, in these civilised days, tolerate the way a Chinese cook serves any kind of bird?… If left to his own devices the average Chinese cook will serve up the same kind of meals day in day out for all time. In a bachelor mess where the occupants cannot spare the time to deal with cookie this is unavoidable, but where there is a woman in the house it is little short of a disgrace… It is up to the women in Malaya to break down these awful “customs of the country”. If we only take the trouble to try and teach cookie something of Western ideas and Western methods we shall not find him too unintelligent… But we must have patience and be willing to teach him, often showing him the same thing over and over again.”39

The mem was encouraged to acquire cooking and housekeeping skills so that she could instruct the cook using practical demonstrations instead of trying to explain her wishes in halting Malay. On top of cooking and Malay language classes at the local Young Women’s Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.), it was also useful for the mem to set aside a small room for use as a private kitchen, where she “would be free to make experiments without the embarrassment of servants being present to witness any failures”. The beginner is advised to proceed methodically and to persevere as she must first “accustom herself to the working of the stove, and, with the aid of a good cookery book, gradually work through a whole menu, while trying one item only at a time”.40

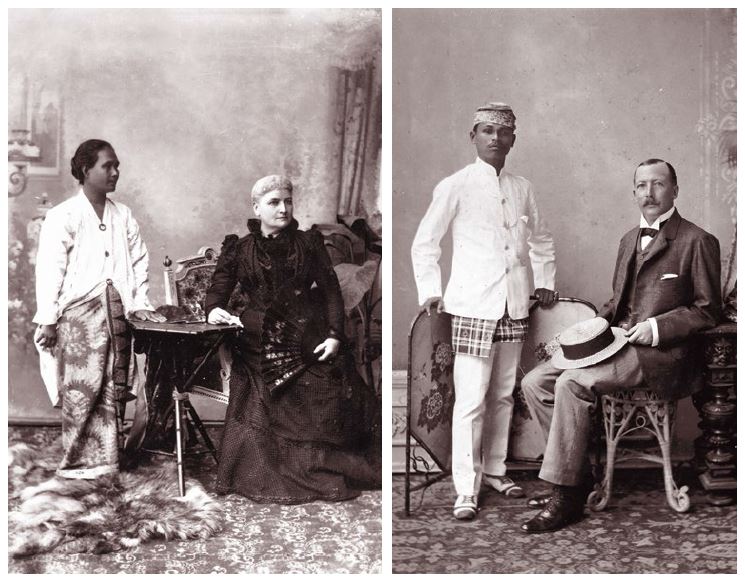

Portraits of Europeans and their servants in Singapore at the turn of the 20th century. The class divide between local people and their colonial masters is readily apparent in these two images, with the servants, albeit well groomed and attired, standing beside their seated European employers. Servants were often included in such commissioned photographs as they were an indication of wealth and status. It was not uncommon for well-to-do Europeans to send such studio photographs to family and relatives back home. Photos courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Portraits of Europeans and their servants in Singapore at the turn of the 20th century. The class divide between local people and their colonial masters is readily apparent in these two images, with the servants, albeit well groomed and attired, standing beside their seated European employers. Servants were often included in such commissioned photographs as they were an indication of wealth and status. It was not uncommon for well-to-do Europeans to send such studio photographs to family and relatives back home. Photos courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Closing One Eye

Cookbooks like The “Mems” Own Cookery Book and The Y.W.C.A. International Cookery Book of Malaya (see text box above) and other well-meaning domestic advice espoused the ideal of a well-run home that mems could aspire to. In reality, according to one “Sylvia” in a Straits Times article dated 13 July 1906, servants heldthe upper-hand for they “too often regard their services as indispensable, and as for knowledge there is little indeed that they do not know with regard to the exact state of the Tuan’s finance, the Mem’s losses, or gains, at Bridge, and the hundred and one small things which go to form the sum total of a household’s existence in the Far East”.41

A European family taking a carriage ride, circa 1890s. Their male servant is controlling the reins of the horse. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A European family taking a carriage ride, circa 1890s. Their male servant is controlling the reins of the horse. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Persistent difficulties with servants often threw doubts on the abilities of European women to carry out their role. While some attributed the problem to lazy wives who neglected to coach and supervise their domestic staff closely, others were of the view that it was precisely mem’s petty habit of nitpicking and meddling that was the source of all troubles.42 On the difference in managerial styles between the sexes, a male observer commented:

“Men usually have the sense not to bother as long as they get what they want whereas women must, on top of that, get it in their own way. I suspect that a good deal of the “unbelievable stupidity” that women always “have to put up with” from perfectly good servants, is simply “put on” to get even with the mistress for treatment received that was lacking in appreciation of service rendered.”43

Even when the Hainanese servants were being roundly condemned, there were those who spoke up on their behalf, asserting that the Hainanese “respond well to kindly and sympathetic treatment”, which implied that employers ought to reflect on how they behaved towards their servants.44

Picking up on the story of Mrs Muddit and Ah Kwi at the start of this article, the latter, in his defence, alleged that Mrs Muddit had asked him to do the impossible – make a pudding without eggs.45 His attempt to reason with her was met with abuse and he was fired on the spot. When Ah Kwi requested for his wages, mem threatened to go to the police. She then seized the cook by his queue and thrashed him with a piece of firewood. While one may have been mortified at what happened to Mrs Muddit at the outset, it is clear that she was also at fault.46

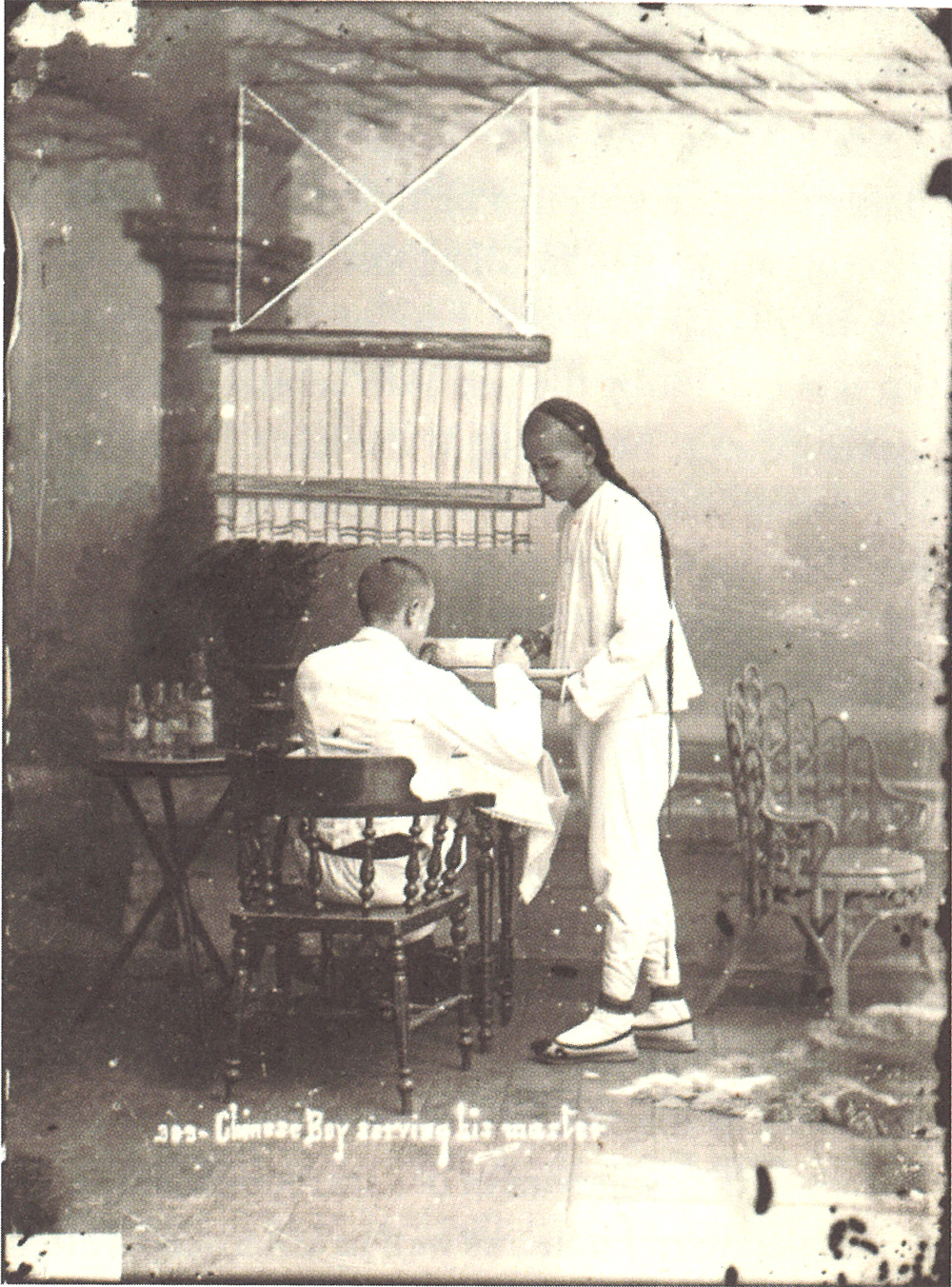

A Chinese houseboy serves his European master who is sitting under a punkah (a large screenlike fan hung from the ceiling and operated by a servant or by machinery). Photo by G. R. Lambert & Co., 1890. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A Chinese houseboy serves his European master who is sitting under a punkah (a large screenlike fan hung from the ceiling and operated by a servant or by machinery). Photo by G. R. Lambert & Co., 1890. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.All in all, successful household management was not so much about bending servants to the mem’s will but rather to administer with a light and even hand. The mistress should pick her battles with care, as Margaret Wilson sagely advises in Malaya: Land of Enchantment (1930):

“The Chinese have their own methods of work and follow a fixed routine they have evolved. It is pretty hopeless to try to instil other methods into their minds – and as to nagging – they simply won’t stand it. I have heard instances where the whole staff has walked out for this reason, and there would be the greatest difficulty in replacing them. The word would speedily go round, and it is a well-known fact that the “East has ears. Therefore, so long as the work is done reasonably well, the wise Mem leaves them alone – only pulling them up occasionally, if the necessity arises.”47

The mem is also urged to respect the off-duty hours for “nothing so disgruntles a servant as to be called in the middle of a nap… to do something that could just as well wait until later”.48 Susan Clinton, the writer at The Straits Times who recommended this principle declared that “an ordered household with a minimum of friction and discontent had been the result”.49

With regard to organising the housework, a roster system may seem sound on paper but in practice could be more trouble than it was worth, given the supervision needed to ensure that servants followed the schedule. “The better plan, and the one which causes the mistress the least grief”, recommended one writer, “is for her to give… a rough outline of what she wants done and let the servants arrange it among themselves”.50

Above all, the mistress should strive to cultivate forbearance and see humour in the exasperating situations that could arise, as deftly captured in Wilson’s words:

“In his daily marketing the cook probably makes a bit for himself on the transaction – that is an understood thing. But, so long as the “bit” is not too blatant, the wise Mem shrugs her shoulders and says “Tid’ Apa” [Tidak apa] What a marvelous phrase! It sums up the whole philosophy of the East. It means “No matter,” and not until a person has reached that stage of being above the petty annoyances incidental to dealing with an alien race, will she settle down to enjoy life in Malaya. It is not always easy but it pays in the long run. When you find the Amah carefully washing your tooth brush in the soapy water in which you have washed your face… the only thing to do is to put your tooth brush beyond her reach. And when you find that your treasured navy-blue shoes have been cleaned with black polish you can only murmur “Tid’ Apa”, and rejoice in the possession of a perfectly good pair of black shoes which, you tell yourself, will go with anything….”51

Losing one’s temper was to risk being the subject of ridicule and gossip. Unlike their employers, the servants in Malaya “don’t rush into print with their tales of woe but give vent to their feelings in the coffee-shop and if they are good mimics, their mistress’s little peculiarities and dramatic rages, furnish hilarious amusement for the audience”.52 In light of this, perhaps the apparent indifference of some mems towards household management was not so much about “laziness” but a pragmatic response to the prevailing circumstances.

A (Not So) Trivial Matter

The aforementioned “Sylvia”, who in The Straits Times article of 13 July 1906 had said that servants often held the upperhand, summed up the master-servant relationship thus:

“The servant question would, at present, seem to be one of the most wearisome little things in Singapore. Go where you will, and when you will, the subject is ever and always being discussed. From a man’s point of view it is a little question, out of all proportion to the amount of time and anxiety wasted upon it. And yet is it so insignificant after all? Are not whole households, in Singapore, more or less dependent on their servants for their comforts?”53

The management of the household and domestic servants may seem a trivial matter next to the masculine enterprise of building the British Empire. Yet one cannot completely divorce the two: by having the mems supervise the servants and the households, the husbands were free to concentrate on their work. In this sense, the efficient organisation of the home had a profound and far-reaching impact on the lives of the European comunity in Singapore and Malaya.

Despite the presence of servants, the setting up and running of a home in the colony was not a walk in the park for European women. The smooth administration of the household called for tact, finesse and most of all, the ability to appear cool and in control even in the most infuriating of situations.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Pudding without eggs. (1907, February 22). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Literally translated as “Madame Boss”, the term is of Anglo-Indian origin and was commonly used by servants and non-whites to address married or upper-class European women during colonial times. “Mem” is likely a corruption of “Madam” while “Sahib” was the term of respect used to address European men in colonial India. ↩

-

Butcher, J.G. (1979). The British in Malaya 1880–1941: The social history of a European community in colonial South-East Asia (pp. 23–24, 134–135, 142). (Call no.: RSING 301.4512105951033 BUT) ↩

-

The housewives of Malaya. (1933, April 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brownfoot, J.N. (1984). Memsahibs in colonial Malaya: A study of European wives in a British colony and protectorate 1900–1940 (pp. 189–190). In H. Callan & S. Ardener, S. (Eds.). The incorporated wife. London: Croon Helm. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Brownfoot, 1984, p. 196; George, R.M. (1994, Winter). Homes in the empire, empires in the home. Cultural Critique, 26, 95-127, p. 108. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Butcher, 1979, p. 142; Malayan Information Agency. (1932). British Malaya: General description of the country and life therein (pp. 28–29). London: The Agency. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.9 MAL). According to Ashley Gibson, all except the gardener were named as “essential units of the staff required by a European family”, costing some 170 Straits dollars a month. See Gibson, A. (1928). The Malay Peninsula and Archipelago (p. 120). London: J. M. Dent. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.9 GIB) ↩

-

According to comments by the Superintendents of the censuses of the Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States and Other Malay States for the years 1921 and 1931. See Nathan, J.E. (1922). The census of British Malaya (p. 83). London: Waterlow. (Call no.: RRARE 312.09595 MAL; Microfilm no.: NL7366); Vlieland, C.A. (1932). A report on the 1931 census and on certain problems of vital statistics (p. 81). London: Crown Agents for the Colonies. (Call no.: RRARE 304.6095951 FED; Microfilm no.: NL3005) ↩

-

MacCallum Scott, J.H. (1939). Eastern journey (p. 15). London: Travel Book Club. (Call no.: RCLOS 959 MAC) ↩

-

“European women, the cookie and the kitchen.” (1940, May 9). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lockhart, R. (1936). Return to Malaya (p. 110). New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 LOC) ↩

-

MacCallum Scott, 1939, p. 14. ↩

-

Vaughan, J.D. (1879). The manners and customs of the Chinese in the Straits Settlements (p. 20.). Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Hylam v. European. (1891, September 1). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1901, May 3). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The servant problem. (1926, April 24). The Malayan Saturday Post, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Cookie.” (1929, October 26). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Roper, H.B. (1891, September 1). Our Hylam servants. Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wednesday, May 1, 1901. (1901, May 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Settlements. Legislative Council. Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements for 1886 (1886, November 23). Papers laid before the Legislative Council by Command of His Excellency the Governor. Registration of Domestic Servants. (No. 44, p. C655). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Microfilm nos.: NL1107, NL1112) ↩

-

Straits Settlements. Straits Settlements Government Gazette. (1887, January 7). The Domestic Servants Ordinance 1886 (Ord. XXIII of 1886, pp. 11–14). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGSS; Microfilm no.: NL1016) ↩

-

Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 7 Jan 1887, Ord. XXIII of 1886, pp. 11–14. ↩

-

Song, O.S. (1923). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (pp. 238–239, 482). London: John Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Registration of domestic servants. (1912, July 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tuesday, July 23, 1912. (1912, July 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The servant problem. (1905, April 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Song, 1923, p. 482; Servants’ registration. (1914, March 19). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 Apr 1933, p. 1. ↩

-

The world of women. (1935, September 19). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wood, M. (1929). Malay for mems (pp. 5, 7, 10, 12, 14, 21). Singapore: Kelly and Walsh. (Call no.: RRARE 499.18 WOO; Microfilm no.: NL9824) ↩

-

Registration of servants. (1911, July 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 5.Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Times Weekly Issue, 1 Sep 1891, p. 9. ↩

-

Housekeeping in Malaya. (1926, July 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Our domestic servants. (1891, August 4). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kinsey, W.E. (1929). The “mems” own cookery book (p. 3). Singapore: Kelly and Walsh. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 KIN; Microfilm no.: NL9852) ↩

-

The literary page – New books reviewed. (1930, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Savage-Bailey, K. (1935, August 1). An old resident on Malayan cookery. The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Sep 1935, p. 18. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 26 Oct 1929, p. 15. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Sep 1935, p. 18. ↩

-

The little things of life. (1906, July 13). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lowrie, C. (2015). White mistresses and Chinese ‘houseboys’: Domestic politics in Singapore and Darwin from the 1910s to the 1930s (p. 222.). In V. K. Haskins & C. Lowrie. (Eds.). Colonization and domestic service: Historical and contemporary perspectives. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. (Call no.: RSEA 331.76164091712 COL) ↩

-

The value of the ‘boy’ depends upon the master. (1934, April 29). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Hylam servant. (1926, January 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 22 Feb 1907, p. 7. ↩

-

Brownfoot, 1984, pp. 196–197. ↩

-

Wilson, M.C. (1930). Malaya: Land of enchantment (pp. 78–79.). Amersham: Mascot Press. (Call no.: RRARE 915.95 WILL; Microfiche no.: NL0007/027–028) ↩

-

Servants have only one pair of hands. (1940, August 8). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Clinton, S. (1939, October 5). Is your household organized? Suggestions for who does what and when. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 8 Aug 1940, p. 1. ↩

-

The Straits Times, p. 1. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Jul 1906, p. 8. ↩