My Grandmother’s Story

An unexpected recollection by her grandmother about her experience of the Japanese Occupation sets Yu-Mei Balasingamchow thinking about unspoken memories and the stories that haven’t been told.

Yu-Mei and her grandmother at the former’s one-year-old birthday celebration.

Courtesy of Yu-Mei Balasingamchow.

Yu-Mei and her grandmother at the former’s one-year-old birthday celebration.

Courtesy of Yu-Mei Balasingamchow.My paternal grandmother and I have never really talked. This isn’t due to any personal acrimony; it’s just the usual generation gap, made all the more difficult as neither of us properly speak the language that the other person is most comfortable with. I live in the world of the English language; my grandmother’s native tongue is Teochew, though like many Singaporeans of her generation (she’s in her late 90s), she also speaks a muddle of other local languages: fluent enough Cantonese and Malay to carry on extended conversations, a decent command of Mandarin (thanks to several decades of watching TV shows on Channel 8, I suspect) and a smattering of English.

As a child, I thought of my grandmother as speaking, quite literally, “broken” English. She didn’t speak complete sentences, but sprinkled sporadic words, from the straightforward “eat” to the multisyllabic “university”, into her multilingual patois. On the other hand, I speak practically no Teochew. In my adult years, we got by in halting Mandarin – my grandmother’s interspersed with the occasional Cantonese, Teochew or Malay term, mine embarrassingly repetitive and stilted as I fell back on the same few phrases at the tip of my tongue.

The language barrier means that my grandmother and I have never really talked about anything in depth. She did with her own children – long, rambling conversations in Teochew, Malay or a lilting combination of both, in which she often brought up old wounds and perambulated around old gossip. With her grandchildren, the exchanges were shorter, more fitful and unnatural, unless there was someone at hand to translate.

So while I’ve always known that my grandmother can be voluble, I’ve never asked her much about her life, and I’ve never been on the direct receiving end of a spiel that I could understand.

One day, almost two years ago, as she and I were sitting down to lunch, she gestured at the television, which was showing the daily Channel 8 news bulletin, and said something in Mandarin like, “Did you watch the news? There’s a war going on.”

My grandmother never talked about the news, so it took me a few seconds to register what she had said, and then I didn’t know if the news she referred to had been about the situation in the Ukraine or the Israel-Gaza conflict.

“When there’s a war, all the prices go up. The cost of food goes up,” she went on as she started scooping food onto her plate of rice.

Any discussion of global economics and the cost of living was well beyond the ability of my wobbly Mandarin, so I just murmured assent.

“I’ve lived through two wars, you know. First when the Japanese came. Then when the British came back.”

My ears perked up.

Scratching Beneath the Surface

I’ve been working as an independent researcher and writer in Singapore’s history and heritage fields for a decade now, and in that time I’ve witnessed a surge in interest in local history, as well as activism around heritage issues. A decade ago, I would not have anticipated the passionate defence and caretaking of Bukit Brown Cemetery by the volunteer group All Things Bukit Brown, or the number of local history- or identity-oriented artworks that emerged from Singaporean artists at the last Singapore Biennale, or that the government would budget $42 million for a Singapore Memory Project to collect memories of Singapore.

My personal interest comes from wanting to find out more about Singapore, past and present, which possesses far richer, more complex and unsettling stories than the airbrushed, whitewashed Majulah Singapura version found in school textbooks or mainstream discourse.

I’m interested in stories that no one used to care about, stories that complicate or overturn the orthodox way of thinking about the present – stories that begin with questions that no one has thought of asking before.

For all the documentation projects, government grants, websites, Facebook pages and knick-knacks that have sprung up around “Singapore heritage”, I’m often reminded that the stories that have not yet been told, the layers that have not yet been peeled back, are often staring us in the face.

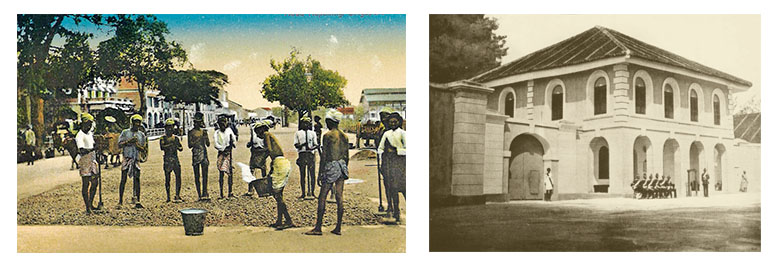

Some years ago, I came across the book Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: A Penal History of Singapore’s Plural Society by Anoma Pieris.1 It examines Indian convict labour in colonial Singapore and how racial politics have been inscribed in our multiethnic society and urban history since its founding. Pieris highlights several colonial landmarks in the civic district that have been canonised as national monuments because of their architecture, an homage to the benevolence of colonial rule. Yet the convicts who built them have gone largely unacknowledged. At Bras Basah Road for instance, where the Singapore Management University now stands, there is no trace or memorial of the prison where the convict labourers were housed.

(Left) A postcard of Indian convicts repairing a road in Singapore. Few people are aware that Indian convict labour was used for the construction of many colonial-era buildings in Singapore. Courtesy of Farish Noor.

(Left) A postcard of Indian convicts repairing a road in Singapore. Few people are aware that Indian convict labour was used for the construction of many colonial-era buildings in Singapore. Courtesy of Farish Noor.Perhaps because I spend so much time in the civic district, Pieris’s observation that we take for granted the historical value of these buildings hit home. I’m reasonably informed about migrant worker issues in Singapore today, but I’ve never stopped to think about the men and women – and there were women labourers, says Pieris – whose hands brought these buildings into such fine form.

Which made me think: what other histories are we missing in plain sight?

Wartime Memories

One historical subject that most Singaporeans have encountered is World War II and the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. My parents were born during the war, so they don’t remember it, but I’ve wondered off and on, as a child and then as an adult, what my grandparents had experienced. It didn’t seem like something I could bring up in casual conversation.

Headlines in the 20 February 1942 and 3 March 1942 editions of The Syonan Times announcing the Japanese invasion of Singapore and Java. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Headlines in the 20 February 1942 and 3 March 1942 editions of The Syonan Times announcing the Japanese invasion of Singapore and Java. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.I’ve heard of school projects where students are dispatched to interview their grandparents, elderly neighbours or other hapless senior citizens about their memories of the war. This has always struck me as a potentially incendiary assignment: what if the older person doesn’t want to recount those memories, and what would a student do if the interviewee became visibly distressed?

I don’t like pushing people to tell stories they’re not ready to tell. Their silences, or refusals to answer, say everything.

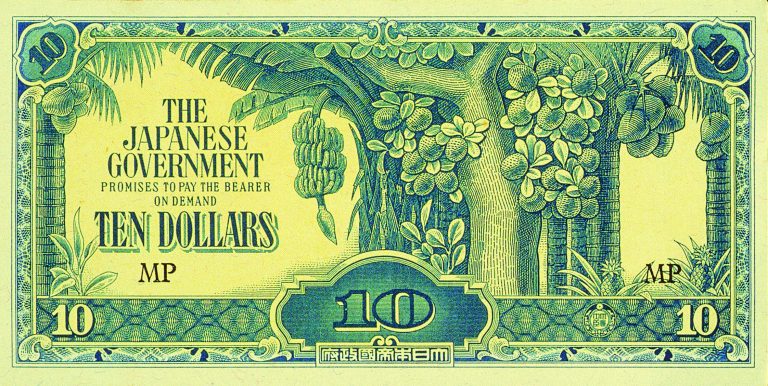

But over that lunch with my grandmother, she needed no urging. A spool of memories seemed to have unravelled of their own will, as clear and taut as if she was telling me about something as mundane as going to the hairdresser. Her story ran backwards, beginning with the return of the British at the end of the war and how they had declared the Japanese “banana” currency worthless, bankrupting entire households overnight. Then she was back at the beginning of the Japanese Occupation, living in northern Singapore with my grandfather and some of her relatives, and they knew that the Japanese were coming.

“I told my aunt to cut her daughter’s hair like a boy and make her wear her older brother’s clothes,” my grandmother said. I’d never heard of any of these people before. “My aunt agreed, so I cut her daughter’s hair for her. That was at about 3 pm. That night, at about 11 pm, there was a sudden banging at the door.”

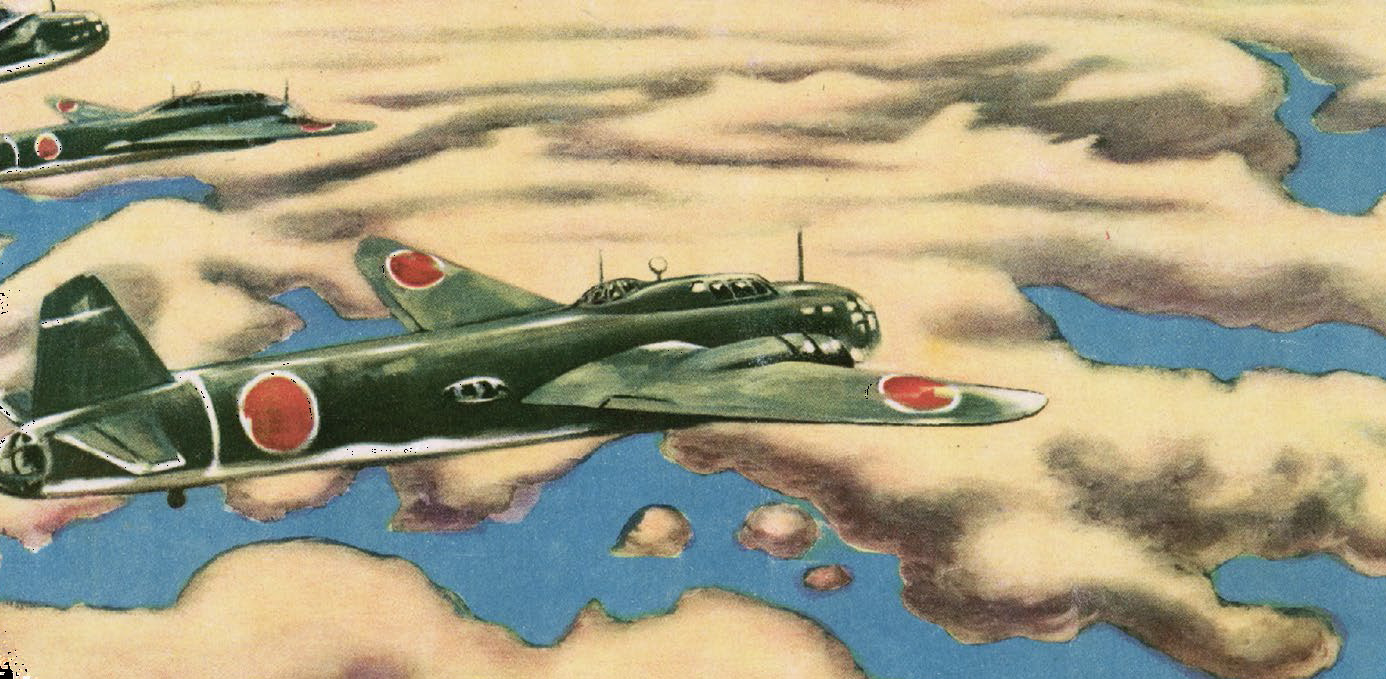

A painting of Japanese naval bombers during World War II. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A painting of Japanese naval bombers during World War II. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.What Has Not Been Remembered

The dominant narrative of World War II in Singapore, as it is for many societies, is of terrible suffering, violence and oppression at the hands of the enemy. In the accounts about Singapore, the dominant tragedy of the narrative is Operation Sook Ching, where Chinese men (though some women and children were swept up as well) had to report to Japanese military screening centres, and thousands were taken away – often arbitrarily, it seemed – to be massacred.

Today, the term Sook Ching often seems synonymous with the Occupation years, and the trauma is writ so large in local history that one might get the impression of a long drawn-out process not unlike the Holocaust, when in fact the Sook Ching episode lasted only 12 days and took place only in the first month of the 3½-year Occupation.

Without diminishing the suffering of the victims of the Sook Ching and their loved ones, it is worth asking: what other histories of the Occupation have been obscured, overshadowed or not spoken? Not that accounts should be set against each other to “compete” in terms of physical violence or psychological trauma, but what else can be added to the spectrum of accounts told, to produce a more multi-faceted narrative of the Japanese Occupation in Singapore?

And how does one even begin to excavate memories that are likely to be traumatic or repressed, whether on an individual or societal level? How do we remember that which we cannot, or will not, remember?

The sociologist Paul Connerton, who studies memory and modernity, has said:

“I think that coerced forgetting was one of the most maligned features of the 20th century. For example, think of Germany after Hitler, or Spain after Franco, or Greece after the colonels, or Argentina after the generals, or Chile after Pinochet: in all these cases, there had been a process of coerced forgetting during the dictatorships.

“And if, on the other hand, you think of some of the distinguished writers [of] the second half of the 20th century – Primo Levi or Alexander Solzhenitsyn or Nadezhda Mandelstam – the interesting thing about them is that they took up their pens in order to combat this process of coerced forgetting. As a result of this, I think that you could say that at the end of the 20th century there was such a thing as an ethics of memory. Memory and remembrance had acquired the quality of an ethical value.” 2

The ethics of memory is not something that we often talk about in Singapore. In the ongoing frenzy to remember, record and archive, we don’t usually pause to ask why we should be doing this – if there is something ethically at risk of being forgotten, denied or erased from existence.

As my grandmother talked about the Japanese showing up in the middle of the night, I didn’t interrupt her with any questions. The news bulletin was still playing on the television, we were still eating our lunch of rice, vegetables and chicken curry.

This is a 10-dollar bill used during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Known as “banana money” because of the motifs of banana trees on the bank notes, the currency became worthless due to runaway inflation coupled with black market practices. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This is a 10-dollar bill used during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Known as “banana money” because of the motifs of banana trees on the bank notes, the currency became worthless due to runaway inflation coupled with black market practices. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.At 11pm that night, she said, there was a loud banging on the door. It was totally dark both outside and inside the house. Three soldiers entered, two Japanese, one Taiwanese, with a torchlight. They were looking for women. My grandmother was holding my uncle, her only child, who was not yet two years old. The soldiers looked over the women in the house, including my grandmother, but the women were all dirty – ang zhang (肮脏), my grandmother said in Mandarin. I don’t know if she meant they were literally covered in dirt or if the term is a euphemism for menstruation or some other taboo. My grandmother said the soldiers glanced at her aunt’s daughter too, but dismissed her as a boy. They left the house after a while, and later she heard that they had raped another woman nearby.

Reading about war atrocities in a textbook often seems distant and unreal, until you realise that those horrible things might have happened to your small, frail grandmother. My grandmother talked and I listened, gingerly, until she reached the end and I could breathe again.

“The next day, my aunt thanked me for saving her daughter, for the idea of cutting her hair and disguising her as a man. I said to her, don’t say like that.” My grandmother went on to other stories, about her, my grandfather and my uncle hiding in a rubber plantation, then walking all the way to Singapore town and finding a place to live. One year later, she gave birth to my father.

Silent Absences

I didn’t mean to make this essay about my grandmother’s story. I set out to write about some of the gaps that persist in Singapore history, and how master narratives can define the way we think about the past or the present – the “lessons” of wartime suffering or the “value” of colonial monuments – to the extent that it becomes almost impossible to see any other experiences and histories that existed in the same space or time. I certainly didn’t attempt to coax any memories out of my grandmother; indeed, when she offered her story, I felt uneasy, as if she had somehow read my mind and discerned what I was going to write about, and was volunteering her own account to go along with it.

I’ve never written about anything that was at once so personal and so distant from my own experience. I have never struggled so deeply, after writing something, about whether to publish it. My grandmother knows I am using her story here – or at least, my father tried to explain it to her as best as he could (we’re not sure if my grandmother understands what the Internet is).

Even so, is it ethical to amplify a story, shared privately, on a public platform? Or does the ethical imperative of memory, as Connerton describes, take precedence?

I think about the woman my grandmother heard had been raped. Whoever she was, whatever became of her, it’s impossible to know now. She is a silent figure on the horizon; we can make her out, though we will never get any closer to her. But we know she is there.

Koeh Sia Yong’s oil painting titled Persecution (1963) showing innocent men dragged to execution grounds by Japanese soldiers. Operation Sook Ching, which took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942 saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. The exercise was aimed at purging Singapore of perceived anti-Japanese elements. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Koeh Sia Yong’s oil painting titled Persecution (1963) showing innocent men dragged to execution grounds by Japanese soldiers. Operation Sook Ching, which took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942 saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. The exercise was aimed at purging Singapore of perceived anti-Japanese elements. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.When we think about the gaps and silences in Singapore history, we typically think of the big political erasures – the experiences of political exiles and detainees, the circumstances of Operation Coldstore or Operation Spectrum. We think of minority groups whose experiences, stories and viewpoints get downplayed or erased.

But there are other kinds of absences. In 2005, the National Archives of Singapore published the scrupulously researched The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 by Lee Geok Boi, which draws on the archives’ oral history records and other collections to provide “a Singaporean and ultimately an Asian view of the Occupation”.3 The index to this book contains three entries for “rape”, consisting of four pages in all, and 30 entries for “Sook Ching”, comprising 45 pages in all.

The dead cannot speak, nor can the mutilated or the traumatised. Their pain still exists, the violence one human did to another resides in their bodies and their minds. I suppose my grandmother, hearing about faraway wars on the news, was thinking about the things that happen to men, and particularly women, in times of war.

Amid the current mania about Singapore history and heritage, and competing claims to historical truth, it is easy to think that people are too obsessed with the past. In a smartphone-powered, social media-fuelled age, it often seems like everything is being “documented” and that everyone is engaged in “documenting”.

But we should also pay attention to the silences – to the people who aren’t speaking, can’t speak or don’t think they have any stories to tell. Not to pester them to tell all, but to be attentive to the silence. Not to interview, but to wait and listen and let them talk, if they ever can.

A longer version of this essay was previously published on Junoesq.com (vol. 1, August 2014). Junoesq is a quarterly online literary journal featuring poetry, fiction and non-fiction by women.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

NOTES

-

Pieris, A. (2009). Hidden hands and divided landscapes: A penal history of Singapore’s plural society. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Call no.: RSING 365.95957 PIE ↩

-

Kastner, J., & Najafi, S. (Summer 2011). Historical amnesias: An interview with Paul Connerton. Cabinet, (42), 8. Retrieved from Cabinet magazine website. ↩

-

Lee, G. B. (2005). The Syonan years: Singapore under Japanese rule 1942–1945. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR] ↩