The Tiger Within

These fanged beasts are by turns both captivating as they are terrifying. Patricia Bjaaland Welch explores the tiger motif in the art and literature of Asia.

Hongli spearing a tiger. One of the many paintings of Prince Bao Hongli who ascended the throne in 1736 as the Qianlong Emperor (1735–96). Artist unknown; ink and colour on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hongli spearing a tiger. One of the many paintings of Prince Bao Hongli who ascended the throne in 1736 as the Qianlong Emperor (1735–96). Artist unknown; ink and colour on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.“Tyger, Tyger, burning bright, In the forests of the night”1

– William Blake

One of the reasons we draw is to capture and share an experience, or express our feelings – whether scratched into a cave’s rocky wall or artfully painted with oil or watercolour. One of the reasons we look at art is because we want to be entertained, to see something captivating or exciting. It is for good reason that the tiger has become one of the most written about and depicted animals in literature and art. Enter the tiger as portrayed in Asia.

China

We know the ancient Chinese found tigers as terrifying and captivating as we do today. Among the earliest depictions of tigers are white jade carvings dating back at least 4,000 years. By the 9th century BCE, we find tiger figurines cast in bronze, usually depicted crouching, their tails either hanging limply or curled up along their backs. These are brutish animals with “large heads and incised, almond-shaped eyes, bared rows of sharp teeth, inward-spiraling ears, oversized paws and claws” 2 and thick tails. Some figurines are etched with deep grooves on their bodies to represent the tiger’s stripes. The similarities in the depiction of these animals in western China to objects found in the Altai Mountains of south Russia suggest an early exchange of art between China and her non-Chinese neighbours.

Western Zhou Dynasty (c.1050–771 BC) bronze tiger with deep grooves etched on its

body to simulate stripes. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Western Zhou Dynasty (c.1050–771 BC) bronze tiger with deep grooves etched on its

body to simulate stripes. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.These early bronze and jade carvings of tigers were once buried with the dead as they were believed to offer protection in the afterlife. According to one source, “one of the oldest pieces of evidence for the protective nature of tigers was the discovery of two large figures formed out of seashells, one a dragon and the other a tiger, on each side of a corpse in a grave at Puyang in Henan province”. 3

Neolithic scenes of adrenalin-charged tiger hunts are captured in the rock art at Daxifengkou in the Helan Mountains of Ningxia 4 in China, the clear predecessors of the lean, athletic beasts of the later Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) caught lunging through the air, tails akimbo, their long, extended tongues emerging from open jaws. The Chinese consider the tiger to be the “king of wild beasts” as the markings on the animal’s forehead resemble the Chinese character 王, which means “king”.

A 10 x 10 cm block-printed Chinese paper

charm, one of a bundle. Printer and artist unknown. The four characters read “White Tiger, Divine Lord”. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.

A 10 x 10 cm block-printed Chinese paper

charm, one of a bundle. Printer and artist unknown. The four characters read “White Tiger, Divine Lord”. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.The image of a head-in-the-air, prancing white tiger is one of the four directional animals (representing west and the seven constellations found there) of ancient China, together with a black tortoise entwined with a snake (north), a red bird (south) and a green dragon (east). These used to be painted on the interior walls of tombs and the sides of coffins to protect the dead from unknown evils as well as to ensure that the deceased remained properly oriented even in the afterlife.

Each animal was also associated with an element – for example the red bird represents fire, while the white tiger symbolises metal, which equates with power. During the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC), metals such as iron weapons that were buried in a king’s grave were said to “metamorphose into a white tiger – king of all animals and lord of the mountains – three days after his burial, and to remain crouching on the grave to protect the king’s spirit and dispose of demons.” 5

China’s military preserved and enhanced the image of the fierce tiger as did the artisans who depicted them on the breastplates of warriors and war deities as a sign of military prowess and bravery. Bounding tigers, just like those seen in the Han Dynasty, were de rigeur decoration on the interior walls of military headquarters as can be seen in popular comic book versions of classical historical novels, such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义). When Chinese ceramists were looking for inspiration for new designs to decorate their art works in the 17th century, they often turned to woodblock prints that depicted scenes from China’s classics, such as The Water Margin or Outlaws of the Marsh (水浒传). One such tableau illustrates the story of Wu Song (one of the 108 “Heroes of Mount Liang”) who defeated a tiger (武松打虎) with his bare hands when he ignored the advice of the local people and ventured into a dangerous forest on his own. The tree branch that broke when Wu Song attempted to use it as a club to fend off the tiger lies at his feet, making the scene instantly recognisable.

Tigers were the ultimate symbol of raw, untamed power in China, but then something happened. Sometime around the first century AD, lions were introduced from Central Asia. Their appearance coincided with the introduction of Buddhism into China, and tigers lost their esteemed position to the new cat in town – which became the powerful protector of the Buddha and the new religion. Lions now guarded palaces and temples, while tigers were relegated as protectors of the common people.

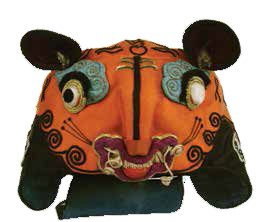

But still powerful, tiger images now appeared on scraps of paper as talismans; mugwort leaves that resembled tiger paws were used to ward off the plague; ceramic pillows decorated with, or made in the shape of tigers became an aid against sleepless nights and nightmares; and young children were dressed in clothes adorned with orange and black stripes and donned caps or shoes decorated with tiger ears so that evil spirits would mistake them as fierce tiger cubs and leave them unharmed. 6

A young boy’s protective cap to fool evil spirits into thinking he’s a tiger cub. The cap is made of orange silk embroidered in heavy black thread with appliqued paws, eyes, mouth and tongue. Whiskers are curled wood shavings. On the back protective neck flap are embroidered the symbols of the Eight Immortals in Chinese mythology. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.

A young boy’s protective cap to fool evil spirits into thinking he’s a tiger cub. The cap is made of orange silk embroidered in heavy black thread with appliqued paws, eyes, mouth and tongue. Whiskers are curled wood shavings. On the back protective neck flap are embroidered the symbols of the Eight Immortals in Chinese mythology. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.When the “Five Poisonous Creatures” (centipedes, lizards, scorpions, toads and snakes) threaten, it was the tiger who was thought to protect one from harm. Embroidered insignia depicting the “Five Poisonous Creatures” and the tiger would be worn by members of the imperial court on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, the date associated with the summer solstice. Superstitious Chinese considered this to be the most dangerous day of the year when the yin force of nature returned, bringing with it darkness and cold. This was also the day when the emperor would perform annual sacrifices and prayers at the Altar of Earth, just as he would perform them on the winter solstice at the Temple of Heaven when the days were longest and coldest, and the yang forces of light and warmth needed entreatment to return.

The use of specific animal images on embroidered squares of cloth sewn onto the front and back of official uniforms to indicate rank within the Chinese military had existed in China for many years before becoming institutionalised during the Ming Dynasty in the late 14th century – the tiger sharing second place with panthers and behind the all-supreme lion. No longer the stalker, tigers were now seen sitting, often with one paw raised in a pose reminiscent of Central Asian felines, alert and curious but not leaping or hunting – their strength apparently dormant until summoned by the emperor. Both the Yongzheng (1723–35) and Qianlong (1735–96) Qing emperors commissioned paintings of themselves hunting tigers.

Tigers and Buddhist Monks

Buddhists regarded tigers as useful metaphors, and not just in the Jātaka tales that document the former lives of the Buddha. One of the most popular of these tales is the Mahasattva Jātaka, which relates how a young man (who would later be reincarnated as the Buddha) sacrifices himself so that a starving tiger mother and her cubs can eat.

More tiger paintings appear in the famous Dunhuang (or Mogao) caves along the fabled Silk Route, including a tiger energetically chasing a devilish-looking figure up a hill (Cave #159) and a frieze in Cave #428 depicting two sleek tigers with oversized comic-book claws. Unlike Indian drawings of tigers which often have elongated triangular faces, these tigers have small, ovoid, monkey-shaped faces with tiny button-like ears.

According to the scholar Helenor Feltham, “images of monks and tigers have a long history in Asian art and culture… [and] can be divided into representations of pilgrim/missionary monks, images celebrating harmony with nature and mastery of primal emotions, and transformative storytellers.” 7 The bestknown image of a wandering monk with a tiger is probably that found by Paul Pelliot – the famous French sinologist – in Dunhuang Cave #17 that dates to the Five Dynasties (907–960)/Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) period, and today kept in the Musée Guimet in Paris. The vividly striped tiger – with fangs exposed and ears turned back alongside its strangely small and flat head – lopes alongside the monk, intent on its march.

One of a pair of tigers on the ceiling of Mogao Cave #428 in Dunhuang, China. Photo by Wu Jian, Dunhuang Academy. All rights reserved, Whitfield, R. et. al. (2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

One of a pair of tigers on the ceiling of Mogao Cave #428 in Dunhuang, China. Photo by Wu Jian, Dunhuang Academy. All rights reserved, Whitfield, R. et. al. (2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.More than one Buddhist arahat – protectors of the Buddhist teachings or dharma – such as Bhadra (in Chinese, Baduoluo), reputed to have been a cousin of the Buddha), or Zen master, were known to have kept tigers as pets. Feng Gan, the 9th-century Chan (Zen) Buddhist monk who introduced the two monks Shi De and Han Shan (later immortalised in decorative art as the Héhé Brothers holding a box and a lotus to represent spiritual peace), was said to own a pet tiger.

One of the most famous paintings of a monk with a tiger, and which also provides a key to understanding the metaphor of the tiger in Zen art, is the artist Shi Ko’s masterful ink work of the Zen master Feng Gan sleeping on his tiger, a depiction that skillfully contrasts the smooth lines of the sleeping monk with the staccato-like brush strokes of the tiger’s fur.

One of the best known Zen stories is that of the Zen monk who encounters a very hungry and aggressive tiger while out for a walk. He tries to flee but the tiger races after him. Eventually, the monk finds himself on the edge of a steep cliff that drops into a rocky ravine. He has no choice other than inch himself over the edge, clinging onto a vine, to avoid becoming the tiger’s meal. But just as he is beginning to hope that he is safe, he notices two small mice, one black and one white, gnawing on the vine. He turns his head, and there, within reach is a beautiful, perfect red strawberry. Holding onto the vine with one hand, he reaches for the strawberry with the other. As he bit into it, he was heard to exclaim, “How sweet this beautiful strawberry is.” And in that moment, he thought life was bliss. The moral of this tale is about seizing happiness no matter what the circumstances are.

The tamed tiger is a popular motif in the Buddhist art of China and Japan, whether it is depicted sitting by the side of an arahat, or accompanying him on his travels, or while alone in quiet contemplation. Ceramic masters in Arita, in the hills of the southern Japanese island of Kyushu, continue to produce exquisite porcelain models of the tamed tiger in the traditional form.

India

– William Blake

In India, on the other hand, a land where tigers once roamed freely and every village feared these dreaded stalkers, the image of the kittenish tiger is nowhere to be seen. Here, “the strongest animals, elephants, form the base of the pyramid of life. The earth is represented by jungle, full of lions and tigers.” 8 This frieze frequently appears on many of the oldest Hindu temples in India, including the caves of Ajanta, Ellora and Elephanta in Maharashatra state.

The famous Tiger Head Cave (Bagh Gumpha), Cave #12 in the Jain cave complex of Udayagiri in Bhubaneswar, India. The opening of the cave is shaped like a tiger’s open mouth. Courtesy of Ruth Gerson.

The famous Tiger Head Cave (Bagh Gumpha), Cave #12 in the Jain cave complex of Udayagiri in Bhubaneswar, India. The opening of the cave is shaped like a tiger’s open mouth. Courtesy of Ruth Gerson.At the 13th-century site of Konarak, dedicated to the Sun god (Surya), on India’s Bay of Bengal, India’s two great religions – Hinduism and Buddhism – are respectively depicted as lions and tigers, each attempting to subdue the other.Contests featuring these mighty beasts were said to have been staged several times throughout history, beginning from the days of the Roman Colisseum, with varying outcomes.

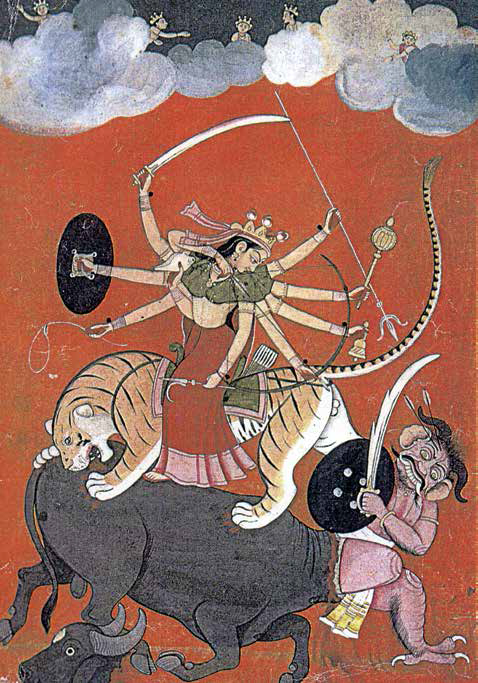

Perhaps this is why there is so much confusion over the goddess Durga when she appears in her most powerful form as Mahisasura Mardini or “killer of the Demon Mahisasura” (who is usually represented as a buffalo). 9 Durga is the supreme divine power, and her mount (either the tiger or the lion) is perfectly matched – the determined hunter and slayer. Occasionally, Durga and her mount are portrayed as such – she with arms flying, holding her arsenal of weapons, and with the tiger (or lion) racing, its mouth open and tail in the air.

The Hindu goddess Durga fighting the buffalo demon Mahisasura. She holds the divine weapons (trident, spear, conch, etc.) given to her by the gods to empower her to slay the demon. Artist unknown; early 18th century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Hindu goddess Durga fighting the buffalo demon Mahisasura. She holds the divine weapons (trident, spear, conch, etc.) given to her by the gods to empower her to slay the demon. Artist unknown; early 18th century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.More typically, however, we find Durga and her mount in a more restful pose – Durga seated in a position of “royal ease”, the tiger (or lion) in profile or facing front, but with all four paws firmly on the ground. It’s the quiet moment after evil is conquered, when both, calm and proud, are content and ready to receive the gratitude of their devotees.

Durga’s consort, Shiva, also wears or sits upon a tiger skin that he has stripped from a tiger sent to kill him. While living as an ascetic and wandering naked through the jungle, he so aroused the local maidens that their jealous husbands conjured up a ferocious tiger to attack him. Shiva’s victory over the tiger represents his power as the ruler and lord of all living things; the tiger’s skin becomes a prayer mat for the ascetic. He has killed not only the tiger, but also all desires. This is why tiger skins are associated with both ascetics and deities in their destroyer personas.

Most Indian art that depicts tigers is religious in nature, with some famous exceptions. The founder of the Mughal Empire, Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad, is more commonly known as Babur (or Babar, Baber or Babür), which literally means “tiger” in Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Urdu. Scenes of birds and animals, including tigers, naturally abound in Mughal art. But probably the most famous (and kitschy) Indian depiction of a tiger is the 18th-century mechanical life-size toy tiger attacking a European soldier (see Tipu’s Toy Tiger).

Tipu Sultan, the owner of the famous mechanical toy tiger, was the ruler of Mysore, India from 1782 to 1799. Such mechanical toys were very popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but none perhaps so gruesome as Tipu’s tiger. Turn the handle of a musical organ hidden inside the wooden beast, and the dying soldier being mauled at the throat wails and flails his arm up and down.The toy was specially constructed for Tipu, it is said, to symbolise his abject hatred for British colonial rule in India. Tipu was fascinated by tigers and had many artefacts decorated with motifs of tigers, including an assortment of weapons, uniforms worn by his soldiers and even his throne. When he died fighting the British, his possessions were seized as loot by the victorious English soldiers. The mechanical tiger was first sent to the East India Company’s India House in London, but was later moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum where it remains today as a curious attraction.

Tipu’s Tiger was created for Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore, South India (1782–99), c.1793. The mechanical toy is made of wood, metal and ivory, and incorporates a musical organ. Artist unknown. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Tipu’s Tiger was created for Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore, South India (1782–99), c.1793. The mechanical toy is made of wood, metal and ivory, and incorporates a musical organ. Artist unknown. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.Tigers were much feared in the villages of India. Collections of thrilling stories revolving around man-eaters were usually heavily illustrated, as were later reminiscences of such famous hunters of man-eating tigers and leopards, such as those penned by Jim Corbett (1875–1955), who authored several works describing his kills. Many a young 20th-century reader developed a life-long reading habit from the tales found in Corbett’s Man-Eaters of Kumaon (1944), or from staying up late at night to read Rudyard Kipling’s story of the young Mowgli who kills the man-eating tiger known as Shere Khan (known to today’s young people through the distorted Disney movie version).

“Brains versus brawn” is the moral behind many Asian legends and fables, usually about a tiger who is pitted against smaller and weaker animals such as a mouse deer or a jackal who inevitably wins the battle with its cleverness. Most of these stories are variations of an old Indian folk tale about a vicious tiger caught in a trap, and who is later released by a foolish but kind-hearted Brahman. The hapless Brahman is then seized upon by the tiger who threatens to devour the man unless he can find a creature who thinks he should not be eaten. Eventually, it takes a clever jackal to outwit the tiger and shut him back into his cage. Many of the illustrations accompanying such stories have become classic artworks, although their creators are often anonymous.

“No, this is how I got into the cage. Let me show you”, says the exasperated tiger. Illustration accompanying the story, “The Tiger, Brahman and the Jackal” from Fairy Tales of India by Joseph Jacobs. Illustrations by John Dickson Batten, 1892. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

“No, this is how I got into the cage. Let me show you”, says the exasperated tiger. Illustration accompanying the story, “The Tiger, Brahman and the Jackal” from Fairy Tales of India by Joseph Jacobs. Illustrations by John Dickson Batten, 1892. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Tibet

Tibet shares many tiger images with India, although most ignominiously as flayed tiger skins tied around the waists or loins of wrathful demons in paintings and sculptures. Tigers that have managed to escape such fates are used as the powerful vehicles of wrathful demons. In their subdued state, tigers in Tibetan culture represent the triumph of the mind over anger into wisdom and insight.

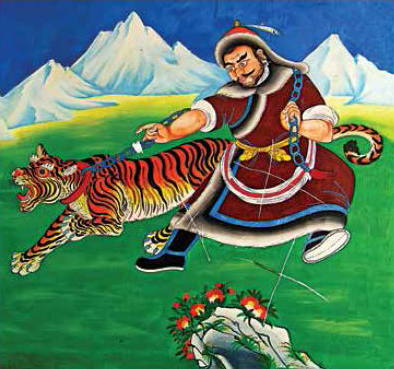

In Southwest China along the border with Tibet and also in Tibet itself, one often encounters brightly coloured murals on monastery walls – awash in primary colours – of a Mongolian lama (identifiable by his hat) leading a tame tiger on a chain across a valley or down a mountain range. The lama is said to represent Avalokitesvara (the embodiment of perfect compassion), the chain represents Vajrapani (protector of the historical Buddha), while the vividly striped tiger is Manjusri, who symbolises wisdom.

Detail of a mural depicting a Mongolian lama leading a tamed tiger on a chain, seen on the wall of a small Buddhist monastery near Zhongdian in Yunnan, China. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.

Detail of a mural depicting a Mongolian lama leading a tamed tiger on a chain, seen on the wall of a small Buddhist monastery near Zhongdian in Yunnan, China. Courtesy of Patricia Bjaaland Welch.According to Robert Beer, “this emblem also has a sectarian symbolism, with the lama leading the tiger representing the supremacy of the ‘yellow-hats’ of the Gelugpa School of Buddhism over their ‘tamed’ rivals, the ‘red-hats’ of the old schools of Tibetan Buddhism”. 10

Thailand

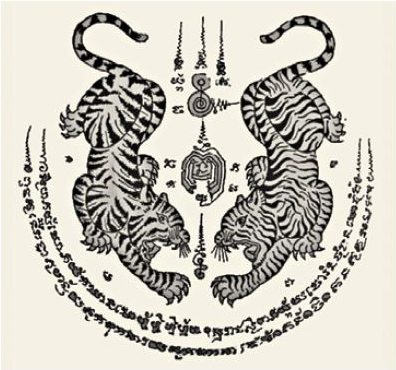

There is a saying in Thailand, “The mosquito is more dangerous than the tiger”, but that doesn’t stop the Thais from invoking the spiritual and physical power of tigers in their daily lives and art. Tattoos depicting tigers, single or in pairs, are considered as powerful and protective talismans in Thailand and especially popular among muay thai boxers. These are tigers with outstretched claws, leaping or stalking, jaws open with bared fangs, who not only endow their owners with enhanced strength but also drive away evil spirits when applied properly by specially trained monks. A carved tiger’s tooth is a coveted amulet among Thais, said to protect its owner and bring good fortune.

Tigers are among Thailand’s most popular talismanic tattoo designs. Courtesy of http://designs-tattoo.com

Tigers are among Thailand’s most popular talismanic tattoo designs. Courtesy of http://designs-tattoo.comStatues of standing tigers (usually carved from wood or made from plaster) are often found on the grounds of Thailand’s Buddhist temples where they serve as symbolic spiritual protectors, but there is a darker side to Thailand’s “tiger temples”. Until very recently, some of these temples bred and raised tigers to sell their parts and skins, and accepted fees from tourists to enter their cages and be photographed with them.

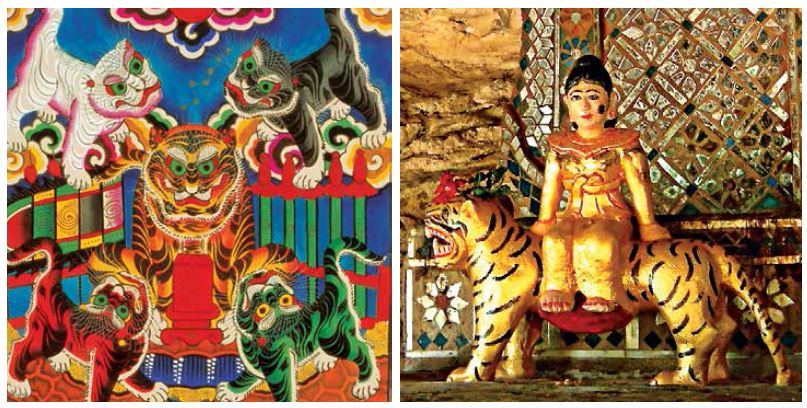

Myanmar and Vietnam

Thailand and Myanmar (Burma) share a common belief in assigning each day of the week its own icon. In Thailand, this takes the form of different depictions of the Buddha, but in Myanmar, the differentiation is made by assigning an animal from the Burmese zodiac to each day (with two animals for Wednesday, the birthday of Buddha). A tiger represents Monday, and contrary to China, the direction east.

Most tiger figurines in Myanmar are carved from wood or made from plaster moulds, and somehow manage to look both ferocious and friendly at the same time. The gaping mouths show sharp fangs and teeth, yet the lips seem to curl back to form a smile. Traditional Burmese lore recommends that tiger’s claws be placed around an infant’s neck as protection against infantile ills, and tiger’s milk as natural immunisation against infections. 11

Because tigers are believed to embody Monday’s personality traits, they are moody and cunning enough to serve as decorative mounts for figurines and sculptures of nat spirits in Burmese folk religion. On the other hand, the overly confident tiger is often duped by clever little rabbits, who are almost always the heroes of Burmese animal folktales.

(Left) A Vietnamese woodblock print depicting the five tigers that represent the Daoist cosmological symbol of the “five points of the compass” or the five elements – earth, wind, fire, water and metal, 2001. The artist is Le Dinh Ngien, one of the last printmakers of the Hang Trung style. Courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum, National Heritage Board.

(Left) A Vietnamese woodblock print depicting the five tigers that represent the Daoist cosmological symbol of the “five points of the compass” or the five elements – earth, wind, fire, water and metal, 2001. The artist is Le Dinh Ngien, one of the last printmakers of the Hang Trung style. Courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum, National Heritage Board.Vietnam, strongly influenced by Chinese culture, adopted the model of the five directions, but instead of using four different animals and a central motif, substituted these with five coloured tigers – the traditional orange and black striped tiger in the centre, surrounded by white, black, red and green tigers. While the tiger in the centre crouches, the surrounding four stand on four feet, tails erect.

Singapore

While tigers do not figure prominently in the art and literature of Singapore, they have certainly left their pawprint on its folklore and culture. One of the first encounters took place in in 1835 when the Government Superintendent of Public Works, George D. Coleman, and his team of Indian labourers were supposedly attacked by a tiger while conducting a survey in the outskirts of the town. The event was later captured – complete with the tiger springing midair as Coleman jerks backwards and the labourers scatter in all directions – in an iconic painting now on display at the National Gallery Singapore. Visitors seem drawn to it and invariably step in closer to study the scene.

This print depicts G. D. Coleman, Government Superintendent of Public Works, and a group of Indian labourers being attacked by a tiger while conducting a survey in the outskirts of the town in 1835. Fortunately, the tiger crashed into Coleman’s surveying equipment and ran away, leaving everyone unscathed. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This print depicts G. D. Coleman, Government Superintendent of Public Works, and a group of Indian labourers being attacked by a tiger while conducting a survey in the outskirts of the town in 1835. Fortunately, the tiger crashed into Coleman’s surveying equipment and ran away, leaving everyone unscathed. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Early settlers in Singapore were terrified of the many tigers that once inhabited the island. Tiger attacks became so commonplace in Singapore by the middle of the 19th century that a bounty was given out by the government for every tiger killed. The tiger that was shot under the billiard room of the Raffles Hotel in August 1902 was apparently a circus beast that escaped from captivity and accidentally made its way to the iconic hotel. 12 Reputedly, the last wild tiger on the island that roamed the Choa Chu Kang area was killed in October 1930.13

Members of the Straits hunting party with the tiger they had shot at Choa Chu Kang village in October 1930. From left: Tan Tian Quee, Ong Kim Hong (the shooter) and Low Peng Hoe. Tan Tuan Khoon Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Members of the Straits hunting party with the tiger they had shot at Choa Chu Kang village in October 1930. From left: Tan Tian Quee, Ong Kim Hong (the shooter) and Low Peng Hoe. Tan Tuan Khoon Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.It was the drawing of a prowling tiger on a 1920s Straits Settlements 50-dollar note that helped influence the Burmese Chinese entrepreneur Aw Boon Haw to relocate his family’s medicinal ointment business, trademarked Tiger Balm, from Burma to the port city of Singapore. Boon Haw, “the gentle tiger”, together with his younger brother Boon Par, “the gentle leopard”, had inherited their father’s business upon his death in 1908.

The first Tiger Balm factory in Singapore was located on Neil Road and as the business grew – undoubtedly helped by the Chinese belief in the power and medicinal efficacy of tigers – Tiger Balm became a household name. When Boon Haw built a mansion on one of the highest hills in Pasir Panjang for Boon Par in 1937, it included a large garden called Haw Par Villa (or Tiger Balm Gardens) that was open to the public. Over time, an educational theme park was added with tableaux representing traditional Chinese mythologies and folk tales.

The brothers have long since passed on, but Tiger Balm and Haw Par Villa remain. Taken over by the Singapore Tourism Board in 1988, the park was one of Singapore’s most iconic landmarks for many years. Today, Haw Par Villa has its own Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) stop on the Circle Line.

Singaporeans today are more used to tigers as brand icons than lurking threats. Take, for example, Tiger Beer. Who doesn’t recognise the bright blue design with a circle enclosing a black-and-orange striped tiger? The brand is virtually sold around the world but it began life as Singapore’s first locally brewed beer in 1932. Originally marketed as a “tropical lager” targeting young men, today it has repositioned itself, claiming to be “an iconic embodiment of the Asian city on the verge of a breakthrough.” 14 So what is it about the allure of tigers that so captivates us in Asia? It could be that the tiger represents those elements of our human makeup that define us all – sometimes the beast, sometimes the hunter, but at other times hunted and tamed, and occasionally even the gullible chump.

Patricia Bjaaland Welch is a retired university lecturer in symbology and Asian art history. Originally from the US, she has been a permanent resident in Singapore since 1995, and is a frequent contributor to publications on Asia. Her most recent book is Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Imagery (Tuttle, 2007).

Patricia Bjaaland Welch is a retired university lecturer in symbology and Asian art history. Originally from the US, she has been a permanent resident in Singapore since 1995, and is a frequent contributor to publications on Asia. Her most recent book is Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Imagery (Tuttle, 2007).Notes

-

Opening lines of the poem “The Tyger” by the English poet William Blake. ↩

-

So, J. F. , & Bunker, E. C. (1995). Traders and raiders on China’s northern frontier (p. 116). Washington D. C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Call no.: RART 745.0931 SO ↩

-

Yang, X., & Yang, Y. (2000). Chinese folk art (pp.19–20). Beijing, China: New World Press. Call no.: RART 709.51 YAN ↩

-

Bradshaw Foundation. (2011). The rock art of Inner Mongolia & Ningxia. Retrieved from Bradshaw Foundation website. ↩

-

Feltham, H. (2012, October). Encounter with a tiger traveling west. Sino-Platonic Papers, 231, 14. Retrieved from Sino-Platonic website. ↩

-

Even the fearsome dvarapala, a door or gate guardian of temples, apparently wore tiger hats as evidenced by a figure in Grotto #3 at the Maijishan Grottoes in Gansu province. ↩

-

Feltham, Oct 2012, p. 5. ↩

-

Bothwell, J. (1961). The animal world of India (p. 177).NY: Franklin Watts. Not available in NLB holdings. ↩

-

Henry Cousens notes “in old Hindu ornament… the more rare an animal, the less true is its delineation…no doubt due to the rarer animals being less available as models, and less often seen, if seen at all…The lion, for instance, is far less true to life than the homely, domesticated elephant or bull, and often it is difficult to tell whether a certain form is intended for that animal or a tiger.” Tigers of course, are indigenous to India and would have been a much more familiar sight. See Cousens, H. (1903– 4). The makara in Hindu ornament. Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, pp. 227–8. ↩

-

Beer, R. (2003).The handbook of Tibetan Buddhist symbols (p. 65). Boston: Shambhala. Call no.:704.94609515 BEE-[ART] ↩

-

Khin, M. C (1984). A wonderland of Burmese legends (p. 120). Bangkok: Tamarind Press, 1984, Call no.:R 392.09591 KHI ↩

-

A tiger in town. (1902, August 13). The Straits Times,p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A tiger visits Singapore. (1930, November 8). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 38. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tiger Beer. (2006). Retrieved from Tiger Beer website. ↩