Beneath the Glitz and Glamour: The Untold Story of the “Lancing” Girls

These cabaret girls were better known for their risqué stage shows, but some also donated generously to charity. Adeline Foo uncovers these women with hearts of gold.

Who were the so-called “lancing” girls of yesteryear?1 They were the glamorous dance hostesses from the cabarets of the “Big Three” worlds of entertainment in Singapore – New World, Great World and Happy World (later renamed Gay World) – who made a living from “lancing”, a local mispronunciation of “dancing”.

From the 1920s to 60s, the “Big Three” amusement parks grew in tandem with Singapore’s development, rising from humble wooden shacks and makeshift kiosks to sophisticated playgrounds offering restaurants, cinemas, cabarets, orchestras and carnival rides as well as entertainment such as Malay bangsawan, Chinese opera, boxing matches, circus acts and Western-style vaudeville shows. The parks were a huge part of people’s lives, and offered something for everyone in the family. In its heyday, some 50,000 people could easily throng an amusement park in a single night.2

By the late 1960s, however, as television and other forms of entertainment such as shopping malls, cinemas and bowling alleys became more widespread in Singapore, these amusement parks went out of business. The New World site at Jalan Besar is occupied today by City Square Mall, while the Great World site along Kim Seng Road was redeveloped into the sprawling Great World City shopping mall and residences. The Gay World site in Geylang has been zoned for residential projects and is presently unoccupied.

Dancers by Night, Benefactors by Day

People whom I spoke to about the cabaret life would mention how the “lancing girls” were the main draw for the men. For as little as a dollar for a set of three dance coupons, male customers could take the girl of their choice for a spin on the dance floor. But, invariably, the discussion would turn to the most famous “lancing” girl of all time: Rose Chan, a former beauty queen and striptease dancer who joined Happy World Cabaret in 1942. When asked what was it about Chan that was so memorable, many would say it was her audacity to strip completely on stage, or to shock audiences by wrestling with a live python in her acts.

The most famous “lancing” girl of all time was Rose Chan, a former beauty queen and striptease dancer, who joined the Happy World Cabaret in 1942. She was known for her daring moves on stage that included wrestling with a slithering python. All rights reserved, Rajendra, C. (2013). No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.

Not many people were aware that Chan, like other “lancing” girls of that era, was involved in charity work. Perhaps it was an attempt to salvage some measure of self-respect or to assuage a sense of guilt, or maybe it was borne out of genuine sympathy for the destitute as many of the cabaret girls themselves came from poor or dysfunctional families. A pretty face and a comely figure was all that women like Chan could claim. But with the money they earned in the cabaret, they could make the lives of the downtrodden slightly better.

On 27 August 1953, The Singapore Free Press newspaper reported that the princely sum of $13,000 had been raised by the Singapore Dance Hostesses’ Association in aid of the Nanyang University building fund.3 This feat was achieved through several charity night performances that had been staged at various cabarets. Unbeknown to many, Chan was part of the efforts to help raise this money. She wasn’t just the “Queen of Striptease” who titillated men on stage; she was equally generous in donating to various charities that cared for children, old folks, tuberculosis patients and the blind.

Rose Chan wasn’t the only “charity queen” from the cabaret world. There were two other women from the Happy World cabaret who worked tirelessly to start a free school for children. These women became the founders of the Happy School in Geylang.

A Happy School for Children

In 1946, cabaret girls from Happy World answered the call by one of its “big sisters”, Madam He Yan Na, to donate money to set up a Chinese medium school in Singapore. Madam He, the chairperson of the Happy World Dance Troupe (which later became the Happy Opera Society), was deeply troubled by the large number of idle children roaming the streets of Geylang. These were the unfortunate children who had their education interrupted by World War II.

Madam He roped in her fellow dance hostesses to set up the school. She became the chairperson of the school’s board of governors, while another dancer, Madam Xu Qian Hong, took on the role of accounts head. Other girls from the Happy Opera Society became board members.

Determined that the children should receive a free education, Madam He insisted that no school fees would be collected from the families. Whatever books and stationery the children needed were also given free. The first enrolment in 1946 attracted about 90 students. Operating out of a rented shophouse at Lorong 14, Madam He named the school Happy Charity School, in an obvious nod to the most popular landmark in Geylang then – the Happy World amusement park.4

The first principal of the school was Wong Guo Liang, a well-known calligrapher. When Wong first met Madam He at the interview for the position, he remembered being struck by her charisma and generosity. Despite the irony of her situation, she advised him to set a good example as the principal and live up to the responsibility of being a role model for his charges. More importantly, he should never ever step into the Happy World Cabaret.

Madam He related how her impoverished past and the lost opportunity to be educated made her even more determined to help destitute children. She was unshakable in her view that a good education was the key to a better life.5

In an interview published in the Chinese daily Nanyang Siang Pau, Madam He was painfully aware of how society looked down on women like her: “The profession of dancing girls is seen as inferior. If society can abandon its prejudice and be rational, they would understand that they have misunderstood the art of dancing. They are being cruel to cabaret girls due to their ignorance. If dancing is corrupted, then this negative image comes not from the dancers, but the vice that tarnishes the environment. To punish and shame the girls is ridiculous.”6

The second founder of Happy Charity School, Madam Xu Qian Hong, was a classic Cantonese beauty with a heart of gold. An article in the Nanyang Siang Pau, dated 10 June 1947, described her as “enchanting” and “energetic” by turns. Madam Xu became a cabaret girl at 16, having been forced by circumstances to help her father support her younger siblings after her mother died. She only had two years of Chinese education before she joined the dancing profession. As a widely sought after cabaret girl, Madam Xu earned about $1,000 a month, and from out of her pocket she would donate about half of her salary each month to the school.7

What these two women and their comrades did to keep children off the streets and give them a shot at a better life was truly admirable. The shortage of schools in the post-World War II period was even more critical compared with the situation before the war. An article in The Straits Times on 23 November 1947 declared that “Singapore Needs More Schools”.

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore between 15 February 1942 and 12 September 1945 had displaced education and many other essential services, and by 1947, there were approximately 90,000 children of school-going age.8 There was serious overcrowding at schools, insufficient facilities and a severe shortage of teachers. While the situation in English schools was bad, it was even worse in Chinese medium schools.

During the Occupation, Chinese schoolteachers had been systematically targeted in the Sook Ching massacres,9 and many were taken away and executed by Japanese soldiers. Chinese books were also not spared. It was estimated that some 200,000 books were destroyed by the Japanese during this period.10

In the face of this dire situation, Madam He and Madam Xu became actively involved in the running of Happy Charity School while juggling with their evening jobs at the cabaret. Faced with pressing challenges such as rising operational costs and the need to recruit more teachers. The school decided in January 1950 to impose a monthly school fee of between $2.50 and $3.50 per student. Following this move, the word “Charity” was dropped from the school’s name to reflect its new status, and it was renamed The Happy School.11

The Happy School Runs Its Course

For reasons that are not known, the two women founders subsequently left the school after 1950. The Happy School continued operating out of its Geylang location until 1979. The school relocated once in 1947, from No. 24 in Lorong 14 to Nos. 67 and 69, after it received financial help from George Lee, the owner of Happy World amusement park.

In 1946, The Happy School started with 90 students. By 1959, its enrolment had ballooned to about 600 students. Due to insufficient space at its Geylang premises, lessons were conducted out of two rented classrooms at the Mountbatten Community Centre.12

Unfortunately, in the 1960s and 70s, the school witnessed a similar trend seen across all Chinese medium schools in Singapore. As Singapore’s economy shifted towards industralisation and English became recognised as the de facto working language, more and more parents decided to send their children to English stream schools. Dwindling student numbers at Chinese medium schools islandwide eventually sounded the death knell for the Happy School.

In 1979, Happy School announced its closure. By that time, the school had amassed some $400,000 in savings, which the board donated to 10 Chinese schools and grassroots organisations.13 After 33 years, another chapter was closed in the history of free schools for children in Singapore.

The origins of the Happy Charity School may have been controversial – some parents may have frowned upon a school financed and run by cabaret girls – but the good intentions of these women cannot be denied. If not for Madam He and Madam Xu, many destitute children would not have received their primary school education in post-war Singapore.

Jobs for Women in the 1940s and 50s

In my research, I was curious about alternative employment opportunities available to women between the 1940s and 50s when cabaret work was seen as an attractive job. A quick search in the “Job Advertisements” page of local newspapers in 1948 listed several clerical positions available at the National Registration Office of the colonial government (the work entailed issuing paper identity cards to citizens).

Interestingly, a large number of women were also employed as barbers. A Straits Times article on 23 October 1949 reported that an estimated one-third of some 2,000 Chinese barbers in Singapore at the time were young women. It is likely that many women entered the trade because other jobs were hard to come by. Chinese men preferred to have their hair cut by women barbers because they were known to be careful and attentive.

A one-hour job that included a haircut, shampoo, shave and ear cleaning cost $2. The average salary for women barbers at these Chinese hairdressing saloons was $100 a month. In fact, women had been working as barbers even before the war.14 One lady barber was reported as saying that “men like to be attended by girls because we are more gentle with them. We talk and entertain them while doing our work, and even make them laugh sometimes”.15

The limited jobs for women in the 1950s included seamstresses, sales assistants, tour guides, cabaret singers and restaurant waitresses. Many also took to working privately as domestic servants and washerwomen. If a girl was educated, there were more options available to her, such as an office secretary or a private tutor. But many of these jobs didn’t pay as well as that of a cabaret girl. So if a woman was good looking and money was a motivation, dancing in the cabarets provided a means to quick and easy money. A cabaret girl could earn anything between $200 and $1,000 a month. In comparison, a senior clerk working in the government back in 1952 would only earn $280 a month.16 Clearly, some women chose to work in the cabaret as dancing girls because it paid well and few employment opportunities were open to them.

The Glitz and Glamour of “Lancing” Girls

A photo of five dance hostesses taken inside a cabaret in the 1930s. The women are dressed in figure-hugging cheongsams with daring side slits that showed off their legs. They were an obvious attraction for men with their artfully applied makeup and coiffured hair-dos. Courtesy of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

Looking good and well-groomed was part and parcel of the job of a “lancing” girl. Advertisements and pictures from newspapers published during the heyday of these cabarets provide a peek into the fashion sense of the show girls.

The cabaret girls were probably influenced by fashion trends gleaned from entertainment magazines. Like most women in Singapore, they would naturally look towards Shanghai and Hong Kong for inspiration, as these cities were acknowledged as leading fashion capitals of the time.

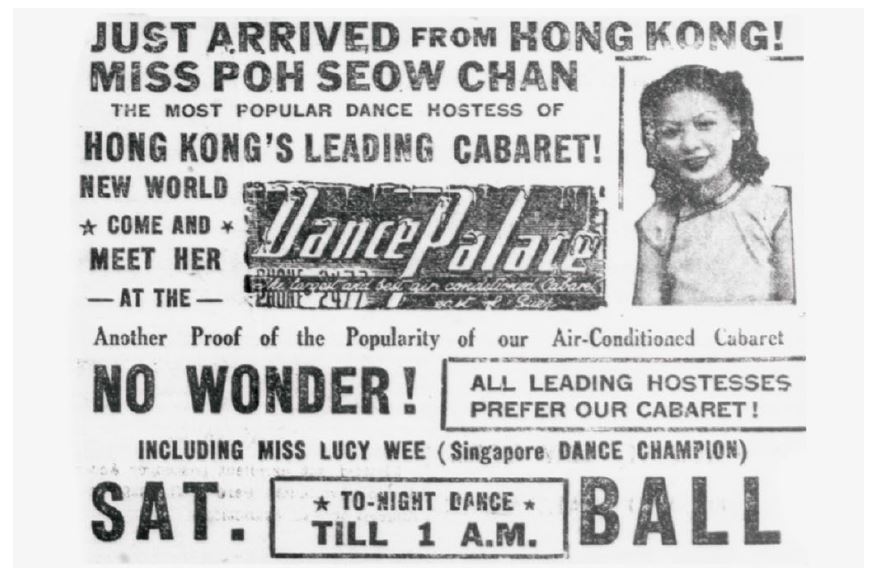

A New World Cabaret advertisement in the 28 September 1940 edition of The Straits Times announcing the arrival of cabaret girl Poh Seow Chan from Hong Kong’s leading cabaret, Dance Palace. The Straits Times, 28 September 1940, p. 2.

A New World Cabaret advertisement in the 28 September 1940 edition of The Straits Times announcing the arrival of cabaret girl Poh Seow Chan from Hong Kong’s leading cabaret, Dance Palace. The Straits Times, 28 September 1940, p. 2.What did Chinese women wear in the 1920s? The samfoo (or samfu) was the preferred casual attire, comprising a cotton short-sleeved blouse with a Mandarin collar and frog-buttons, and a matching pair of trousers in the same material. By the 1930s, however, wealthy Chinese women in the upper social classes had turned to the cheongsam (which means “long dress” in Cantonese), also known as qipao in Mandarin, as their preferred dress.

This adoption of the cheongsam soon cut across all segments of the Chinese population, with the elegant and form-fitting dress worn as a symbol of strong feminine expression. The cabaret girls were no different. In their figure-hugging cheongsam with daring side slits that showed off their legs, they were a sight to behold with their artfully applied makeup and coiffured hair-dos. After World War II, more women turned to wearing Western clothes, but there were those who remained faithful to the traditional cheongsam, and who now wore it with a tighter fit.

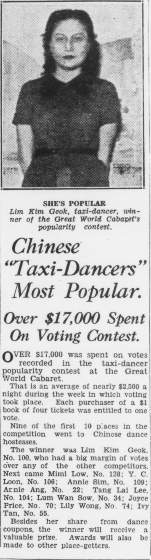

The cabarets at the amusement parks held popularity contests to attract the crowds. A book of four tickets for $1 entitled the purchaser to cast one vote. The cabaret girl who received the most number of votes was declared the winner. Lim Kim Geok (pictured here) was the winner of a popularity contest held at the Great World Cabaret in June 1937. The Straits Times, 10 June 1937, p. 12.

The cabarets at the amusement parks held popularity contests to attract the crowds. A book of four tickets for $1 entitled the purchaser to cast one vote. The cabaret girl who received the most number of votes was declared the winner. Lim Kim Geok (pictured here) was the winner of a popularity contest held at the Great World Cabaret in June 1937. The Straits Times, 10 June 1937, p. 12.Were these attractive women working in the cabaret taken advantage of? Although there was an assumption of a seamier side to the cabaret business, most of the people I interviewed had mostly positive things to say about their experience. A former cabaret woman whom I interviewed, Madam Ong Swee Neo, shared: “I was 12 years old when my mother brought me into the cabaret. All I had to do was sit, chat and dance. I was big sized. No one could tell my real age. Customers were kind. They never forced me to drink hard liquor. I would only drink Green Spot or Red Lion orange crush.”

Madam Ong eventually left the cabaret three years later to get married. I asked her if she missed the glitzy world, she said no: “We were poor, I had little education, my mother was also a cabaret girl. It was a good job that paid well. It was something I would never forget.”17

Johnny Chia, in his 60s, a former singer at the Happy World Cabaret whom I interviewed, recalled the cabaret girls he had known and respected: “They were so beautiful in their cheongsams! Many of them were natural beauties who wore little makeup. They loved music and they loved dancing. It doesn’t matter what I was singing, whether it was Western, Cantonese or Baba Malay songs, they would know the steps.”18

From the late 1960s to 70s, the cabaret, or “nite clubs” that they had evolved into, was still the preferred place of entertainment for the affluent. Thomas Wong, a master tailor and owner of The Prestigious boutique (with shops in Boat Quay and Yishun today) started off as an apprentice at West End Tailors in High Street in 1963 when he was just 16 years old.

His tailoring career in the subsequent years saw him working at various upmarket shops. He recalls clients from Malaysia and Indonesia, which included businessmen as well as members of the political elite, who would come to him to have their suits tailored. For after-dinner entertainment, his customers would frequent two popular haunts, the Flamingo Nite Club at Great World amusement park and the Golden Million Nite Club at Peninsula Hotel. “It was all respectable dancing. Everyone was out to have fun and relaxation. The women were in dresses, and my customers in suit and tie.”19

The Cabaret is Enshrined as a Musical

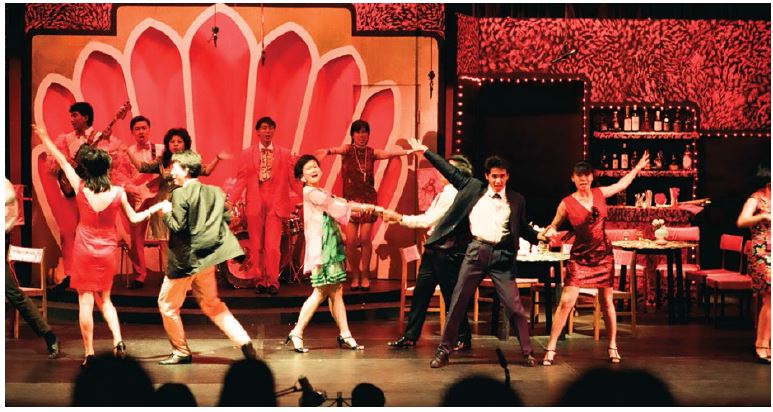

The cabaret isn’t just something only older Singaporeans remember. Younger Singaporeans were given a peek into the scene when Beauty World, Singapore’s first English musical, was staged as part of the Singapore Arts Festival in 1988. Writer Michael Chiang, songwriter Dick Lee, choreographer Mohd Najip Ali and director Ong Keng Sen would continue to headline the local performing arts scene for several decades afterwards. The cast featured actors such as Claire Wong, Ivan Heng and Jacinta Abisheganaden, who would all become familiar names in Singapore’s theatre fraternity.

Set in the 1960s, Beauty World tells the story of a small-town Malaysian girl, Ivy Chan Poh Choo from Batu Pahat, who travels to Singapore to uncover the mystery of her parentage. Her only clue to finding her father is a jade locket inscribed with the words “Beauty World”, which leads her to join the seedy cabaret where most of the action unveils. Within the complex world of scheming cabaret girls and lascivious men, Ivy has to find her feet and still remain true to her boyfriend Frankie.

The cabaret inspiration for the musical was replete with music and lyrics reminiscent of the cha-cha-cha dance era. When asked why he set the story in a cabaret, Michael Chiang explained that the cabaret was “something nostalgic that was also unique to Singapore”. Ong Keng Sen in a commentary published in Private Parts and Other Play Things: A Collection of Popular Singapore Comedies said, “… Michael’s plays are charged with a raw community energy and pride which reverberates in the theatre. His work crosses language and racial boundaries by celebrating our Singaporeanness rather than by dividing us.”20

The cabaret of yesteryear Singapore is indeed a celebration of our unique history and identity. The cabaret was a product of its time, and its indelible “Singaporeanness” was evident from the lives of the women whom I was able to research and interview. All of my interviewees spoke of the past with a certain whimsical longing; even the former cabaret women whose lives had been scarred by pain and struggle had shared their bittersweet stories with quiet pride.

When asked if there was anything in their past they wished they had done differently, all the replies were negative. If these “lancing” girls had a chance to relive their lives all over again, they wouldn’t change a thing. In spite of the underlying exploitation of women’s bodies and the seamier side of cabaret life, theirs were inspiring stories of faith, hope and, as we now know, charity.

WHERE FICTION MIRRORS LIFE (By Michelle Heng)

Singapore’s quest towards modernity in the aftermath of World War II (1942–45) and its nation-building years was underpinned by a quick succession of steel-and-glass skyscrapers and fancy shopping malls. But scratch beneath the surface and a very different side of Singapore emerges − reflected in the lives and loves of several characters from fiction who struggled to make a living in the city’s seamier entertainment spots. A selection of significant works in the National Library’s collection tell an interesting tale of life in a bygone era.

Penned by the late Lim Chor Pee (1936–2006), the plays Mimi Fan (1962) and A White Rose at Midnight (1964) centre on highly-educated male protagonists entangled in relationships with nightclub ladies.21 Set against the backdrop of a modernising Singapore, the plays explore an emerging Singaporean identity during the heady era of socio-political changes in the 1960s.

First staged in 1962 at the Cultural Centre (later renamed Drama Centre), Mimi Fan, in particular, broke new ground as it was uncommon then for non-expatriate-produced plays to be staged in Singapore 22 Lim wanted his play to be as realistic as possible with colloquialisms that Singaporeans could identify with.23 He highlighted the significance of breaking away from the mould of “Western drawing-room drama” in a 1964 article for Tumasek journal, declaring that, “… A national theatre cannot hope to survive if it keeps on staging foreign plays.”24

The eponymous protagonist from Mimi Fan, a free-spirited and independent teenage bar girl, eventually leaves her lover, Chan Fei-Loong, an overseas English-educated Singaporean who has returned home to work, at a time when most women were expected to find value and meaning through their roles as wives and mothers. Another memorable character who existed on the periphery of polite society is Lucy, the Singaporean bar girl who has an affair with the protagonist Kwang Meng in the late pioneer writer Goh Poh Seng’s novel If We Dream Too Long (1972).25

Writer and literary critic Kirpal Singh notes that Singapore’s first post-independence English novel26 was written “around the time Singapore was starting to get − and assert − a sense of itself as a nation” and projected an unnerving anxiety especially as “… Merger with Malaysia had come and gone and left in its wake a stark reality which many were trying to analyse, understand and even project.”27 Amidst this gnawing unease, the struggling protagonist found some degree of solace, albeit shortlived, in the arms of his paramour, Lucy, who earns a living entertaining men at Paradise Bar.

But like the proverbial fallen woman with a heart-of-gold, Lucy chooses to leave Kwang Meng despite a keen affection for him as she fears the judgment of a less-than-forgiving society. In a poignant scene where Lucy rebuffs Kwang Meng’s offer of marriage, she echoes the social mores of a largely conservative society when she exclaims “… I know you men. You will never forget about my past. You say you can, but I know that you can never forget. You will always blame me. Deep, deep inside.”

These seminal works − Lim’s two plays are widely seen as the first conscious attempts to create a Singaporean theatre in English, and Goh’s debut novel was also a first in post-independence Singapore – reflect the plight of working class women who were plying their trade in shady nightspots. Were these women a collective reflection of the “quietly desperate” lives plagued by restless anxiety and uncertainty in a nation that was at the time treading a rocky path to true independence?

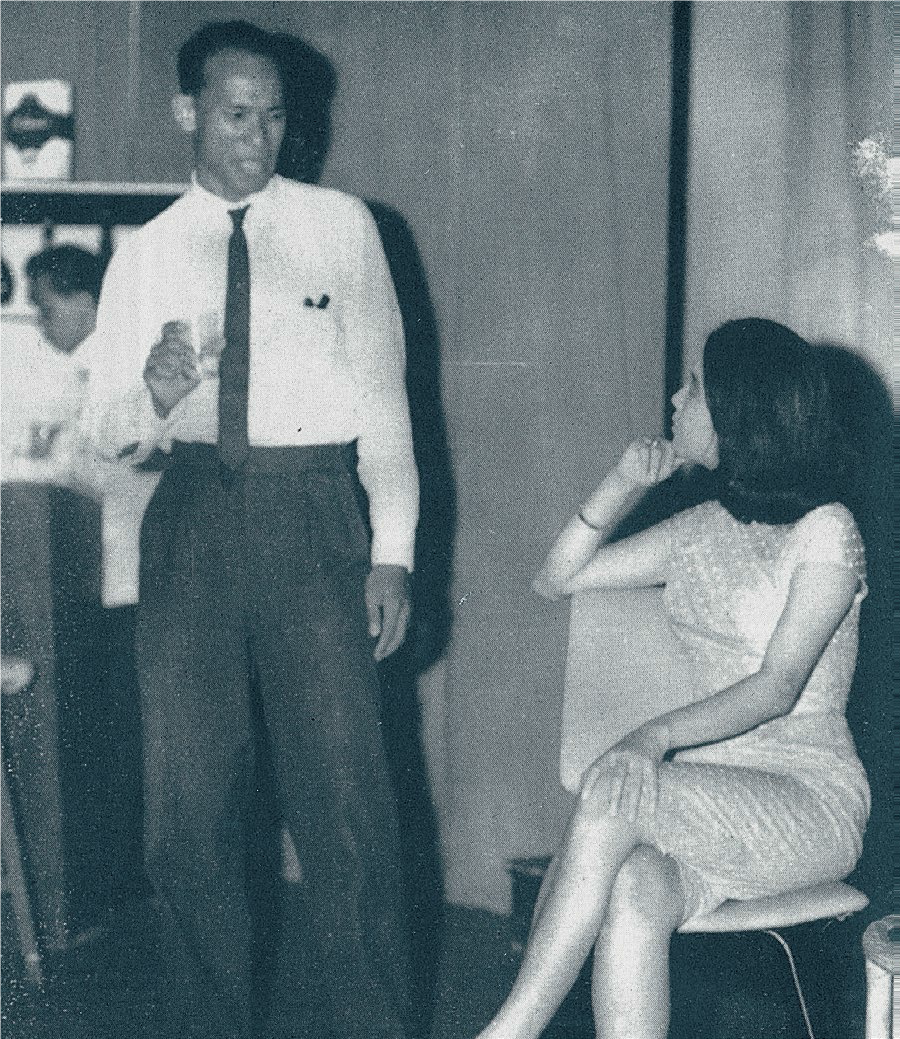

Mimi Fan, a seductive quest for love, escapism and courage, was a trail-blazer in 1960s Singapore at a time when Western “drawing room dramas” took precedence over homegrown productions. Pictured here are Chan Fei-Loong, played by Lim Teong Quee, and Mimi Fan, played by then second year law student Annie Chin. All rights reserved, Lim, C.P. (2012). Mimi Fan. Singapore: Epigram.

Mimi Fan, a seductive quest for love, escapism and courage, was a trail-blazer in 1960s Singapore at a time when Western “drawing room dramas” took precedence over homegrown productions. Pictured here are Chan Fei-Loong, played by Lim Teong Quee, and Mimi Fan, played by then second year law student Annie Chin. All rights reserved, Lim, C.P. (2012). Mimi Fan. Singapore: Epigram.

Adeline Foo was awarded the National Library’s Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship in February 2016. This article is the condensed version of her research paper submitted as part of the fellowship.

Adeline Foo was awarded the National Library’s Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship in February 2016. This article is the condensed version of her research paper submitted as part of the fellowship. Michelle Heng is a Literary Arts Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia and has edited publications including Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Selected Annotated Bibliography (2012) and Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

Michelle Heng is a Literary Arts Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia and has edited publications including Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Selected Annotated Bibliography (2012) and Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).Notes

-

Foo, A. (2016, April 30). The ‘lancing’ girls from a glitzy world. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Pleasure domes of the past.(1987, July 8). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Club aids cabaret girls. (1953, August 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

王振春. (1990).《根的系列之二》(p. 153). 新加坡: 胜友书 局. Call no.: Chinese RCLOS 959.57 WZC. ↩

-

舞国的一朵青春何燕娜. (1947, January 25).《南洋商报》 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

快乐学校慈善舞后许千红访问记. (1947, June 10).《南洋商报》[Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore needs more schools. (1947, November 23). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Following the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Chinese males between 18 and 50 years of age were ordered to report to designated centres for mass screening. Many of these ethnic Chinese were then rounded up and taken to deserted spots to be summarily executed. This came to be known as Operation Sook Ching (the Chinese term means “purge through cleansing”). It is not known exactly how many people died; the official estimates given by the Japanese is 5,000 but the actual number is believed to be 8-10 times higher. ↩

-

Kua, K.S. (2008). The Chinese schools of Malaysia: A protean saga (pp. 31, 34). Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: Malaysian Centre for Ethnic Centre, New Era College. Call no.: RSEA 371.009595 KUA ↩

-

潘星华.(主编). (2014). 《消失的华校:国家永远的资产》(p. 140). 新加坡: 华校校友会联合会出版. Call no.: Chinese RSING 371.82995105957 XSD ↩

-

Kindest cut by women barbers. (1949, October 23). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Women ousting men from barbers’ shops. (1937, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pay talks: Clerks not satisfied. (1952, August 23). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Interview with Ong Swee Neo on 24 February 2016. ↩

-

Interview with Johnny Chia on 19 February 2016. ↩

-

Interview with Thomas Wong on 26 September 2016. ↩

-

Ong, K.S. (1993). Introduction. In M. Chiang. (1994), Private parts and other play things: A collection of popular Singapore comedies (p. 8). Singapore: Landmark Books. Call no.: RSING S822 CHI ↩

-

Lim, C.P. (2012). Mimi Fan. Singapore: Epigram. Call no.: RSING S822 LIM; Lim C.P. (2015). A white rose at midnight. Singapore: Epigram. Call no.: RSING S822 LIM ↩

-

Tan, C. (2014, June 24). Five reasons why the play Mimi Fan is a classic. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Yeo, R. (1982, March 28). Making us speak naturally. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, C.P. (1964, January 1). Is drama non-existent in Singapore? Tumasek, 1, 42–44. Call no.: RCLOS 805 T; The Straits Times, 28 Mar 1982, p. 4. ↩

-

Goh. P.S. (1972). If we dream too long. Singapore: Island Press. Call no.: RSING 828.99 GOH ↩

-

Koh, T.A. (2010). Goh Poh Seng’s If We Dream Too Long: An appreciation. In P.S. Goh. (2010), If we dream too long (p. xii). Singapore: NUS Press. Call no.: RSING S823 GOH ↩

-

Nur Asyiqin Mohamad Salleh. (2016, July 30). In search of the great Singapore novel. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩