From Britannia to the NCO Club

The much-loved NCO Club on Beach Road was a favourite downtown

R & R spot for off-duty soldiers. Francis Dorai charts its history.

Beach Road is a fine example of a street that meshes the new with the old. Along this reclaimed stretch of land is a fascinating mix of low- and high-rise buildings from different eras, influenced by ethnic, Victorian, Art Deco and early Modernist and post-Modernist architectural styles.

Dominating the far end of Beach Road, just opposite Raffles Hotel, are the glass-encased twin towers of South Beach. What is unusual about South Beach is the cluster of low-rise pre-1950s structures that have been preserved by the developer and tastefully integrated within the complex of futuristic towers.

Most of these early Modernist structures are closely connected with the Singapore Volunteer Corps (SVC) – the precursor of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) – whose history dates back to 1854.1 All of the heritage buildings are pre-World War II, save for the NAAFI Britannia Club at the corner of Beach Road and Bras Basah Road that opened in 1952.2 Renamed the SAF NCO (Singapore Armed Forces Non-Commissioned Officers Club in 1974, this is where generations of soldiers in Singapore would unwind and enjoy their rest and recreation hours until the curtain came down on its history some 26 years later.3

The NAAFI Britannia Club

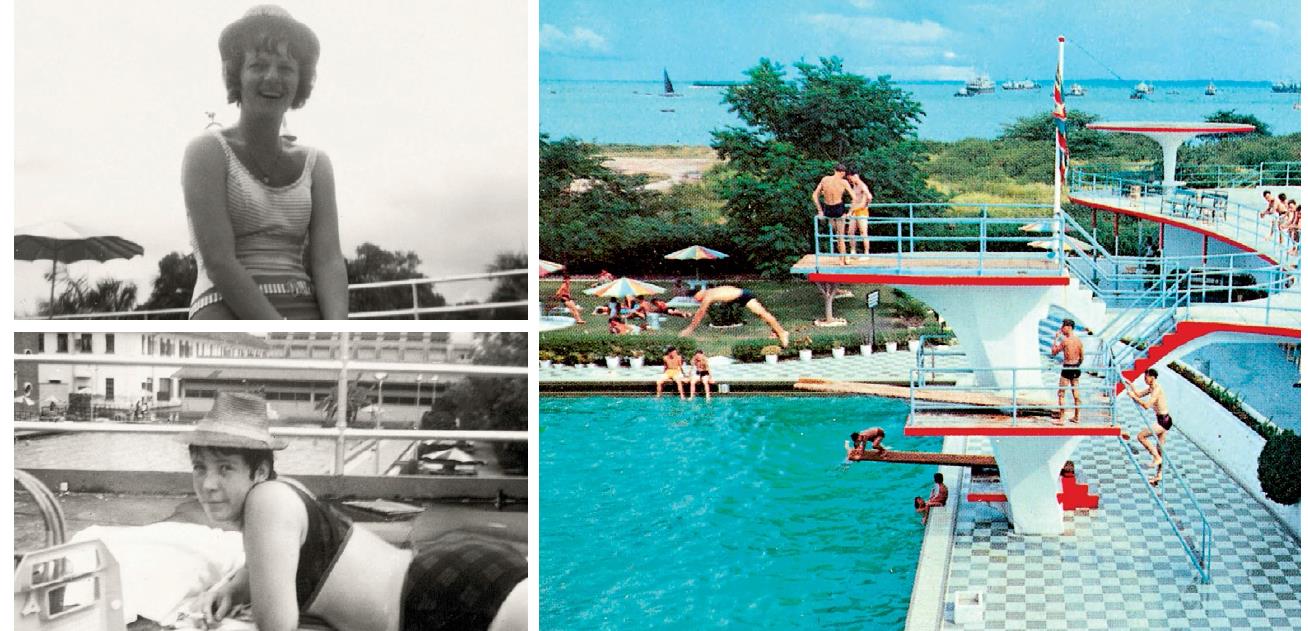

In some ways, Beach Road Camp and the legacy of the SVC have been overshadowed by the NAAFI Britannia Club next door: the siren call of beer, swimming and billiards, among the club’s other comforts, being louder than the call to take up arms. For the British armed forces personnel who served in Singapore in the 1950s and 60s, the Britannia Club was where some of their fondest memories of Singapore were forged.

The club was declared open on 17 December 1952 by Malcolm MacDonald, the British Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia. “The Far East’s most luxurious club for the British fighting forces of land, sea and air” was what the Singapore Free Press reported on its opening day. The clubhouse took 14 months and $1.275 million to build – which was no small change at the time.4 Members of the SVC benefited too as they were allowed access to the club.

The building was funded by the British Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI), which at its peak operated recreational clubs, food and beverage outlets, shops and supermarkets wherever British servicemen and their families were stationed.

The old NAAFI Shackle Club, likely located where the War Memorial Park stands today, had clearly outgrown itself by this time, and a more sophisticated recreational club was needed for the thousands of British servicemen and their families living in Singapore, as well as for visiting Allied forces who called in from time to time.5 With the SVC headquarters next door, the elegant Raffles Hotel opposite and a prime downtown spot facing the shimmering sea beyond, deciding on the location of the new club must have been an easy one.

In fact, Nuffield Swimming Pool – named after the British philanthropist and founder of Morris Motors Company, Lord Nuffield – had been completed a year before the clubhouse was ready and became the focal point of the building. It was one of Singapore’s first Olympic-sized pools, at 50 m long and 20 m wide. The pool was lined with green-and-white mosaic tiles and was framed by a grass verge lined with multicoloured umbrellas. A children’s paddling pool and fountain were located at one end, but most striking of all was the set of three diving boards, perched 3-, 9- and 15-ft above the surface of the glistening pool.6

The three-storey clubhouse created quite a stir when it first opened. Designed by the Hong Kong-based British architectural firm Palmer & Turner, the post-war Modernist structure with its rust-coloured tiled façade and pitched green roof was a bold counterpoint to the Victorian-style Raffles Hotel opposite.

The fittings inside the clubhouse were luxurious and it was clear that no expense had been spared: timber parquet strips, mosaic and terrazzo for the flooring, wall skirtings embellished with Italian marble, concealed overhead lighting and plush furniture. The club’s facilities were equally top-notch: on the ground floor was the air-conditioned pub and main restaurant with a dance floor of polished teak.

In addition, there was an al fresco cafeteria, and a hairdresser and sports shop. Upstairs was an open-air terrace hugging the entire length of the building and providing “a splendid grandstand view of the swimmers and the pool”. Arranged around the terrace were the lounge bar, billiards room, table-tennis room and a music room with a piano. The third floor was reserved for offices and meeting rooms.7

A 1960s aerial view of Beach Road (left) with Raffles Hotel (extreme left), Nicoll Highway (right) and Marina Bay (extreme right). The Britannia Club with its Nuffield Swimming Pool stands on the right side of Beach Road. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A 1960s aerial view of Beach Road (left) with Raffles Hotel (extreme left), Nicoll Highway (right) and Marina Bay (extreme right). The Britannia Club with its Nuffield Swimming Pool stands on the right side of Beach Road. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Party on Britannia

The British Empire may have been on the decline after World War II with its colonies, including Singapore, agitating for independence, but life for the British forces at the Britannia Club was one endless social whirl. Its activity and social calendar published in The Singapore Free Press was jam-packed with events like tombola nights, variety shows, drama and cabaret performances, ballroom and quickstep dance classes, billiards and beer drinking contests.

One of the highlights announced soon after its opening was a “bathing beauty contest for Miss Britannia 1953” in which “servicewomen and servicemen wives… parade round the swimming pool in their smartest swimsuits”.8 The club’s annual Christmas and New Year’s Eve balls were naturally highlights of the calendar with tickets sold out weeks in advance.

Britannia Club holds a special place in the hearts of many former British servicemen and women. Carol Traynor, who served in the Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) in Singapore from June 1966 to April 1967, together with her friend Jenny Nelson, recalls her time at the club: “We used to frequent the Britannia Club after our shifts at Tanglin Camp, taking along a wicker basket packed with food, suntan lotion and books together with a little battery-operated record player. How lovely those days were! We would sunbathe on the terrace above the pool with the blue sea in the distance and music blaring from our portable record player. Coming from blustery and cold England, we loved Singapore’s balmy tropical weather. It was like being on a permanent holiday.”9

The offspring of British servicemen recall blissful times spent at the club. Most of these servicemen and their families lived in rural Changi, Serangoon Gardens and Sembawang because of their proximity to British bases. Driving to the Britannia Club downtown was a weekend treat for the children. John Harper, whose father served as Warrant Officer at the RAF Changi and Tengah bases from 1957–59, remembers the monthly excursions to the club: “The first stop would invariably be the magnificent swimming pool. Dad would head off to the bar to meet other servicemen while mum would keep an eye on my two brothers and I as we swam in the pool – making sure that when we leapt off the highest diving board, which at 15 ft seemed as tall as the Eiffel Tower at the time, we would resurface from the water!”10

BE MY PIN-UP GIRL

Suddenly for a few weeks in March 1956, Wrens, Wracs and Wrafs – acronyms for British servicewomen in the army, navy and air force – at the Britannia Club started primping and preening themselves. The reason: NAAFI in Britain had launched a worldwide “Beauty in Uniform” competition, and the winner could find herself the pin-up girl for homesick British servicemen all over the world. Soldiers were encouraged to send photos of servicewomen in uniform to the NAAFI office in Britain.

The Straits Times reported, rather tongue-in-cheek on 20 February 1956, that “British troops at the Britannia Club Singapore approved enthusiastically when told of the competition… Said Private James Love of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers: ‘First-class idea. I haven’t been here long, but I’ve already met a couple of lasses who could give any film star a run for her money. I am going right out to buy myself a camera!’”11

Exit Britannia

In the late 1960s, Britain’s economy entered a difficult phase and its defence budget was scaled back. On 18 July 1967, the Labour government announced plans to withdraw its troops in Singapore by 1975 – only to revoke this six months later and bring the date forward to 1971. The news was met with much handwringing in Singapore. The sudden pullout by the British meant a severely weakened Singapore, which was still heavily dependent on Britain for propping up both its economy and its defence.12

Singapore’s first batch of national servicemen was still in training in 1967, and the British military bases had been powering the local economy – the cost of maintaining the Singapore Naval Base alone was 70 million pounds a year. In addition, thousands of Singaporeans, including domestic maids and shopkeepers, depended on the British forces for their livelihoods.13 The newly independent Singapore had a raft of issues to grapple with – high unemployment, inadequate housing and pitiably low cash reserves – and this announcement could not have come at a worse time.

But the process had started and there was no turning back. As a compromise, the British agreed to extend the deadline for withdrawal from March to December 1971. Singapore had inherited Britain’s rule of law and the infrastructure it set up, but it was the sudden British withdrawal of support that forced the newly independent country to come into its own. Without Britain to fall back on, the Singapore government had to adopt a series of tough economic measures to put the country on track.

Enter the NCO Club

The Britannia Club closed on 30 April 1971; the pool was drained and the doors and windows shuttered. The poolside picnics, the rambunctious parties and the laughter vanished, and a lone jaga (watchman) was hired to guard the desolate premises. Its closure marked the end of the colour and gaiety that British military life had brought to Singapore.14

A year later, the government negotiated with NAAFI to buy out the Britannia Club and the 63,000 sq ft of prime real estate it sat on. The idea at the time was to convert the premises for public use, but with defence being a priority, a decision was made to turn it into a recreation centre for non-commissioned officers (NCOs) of the Singapore Armed Forces and their families.15

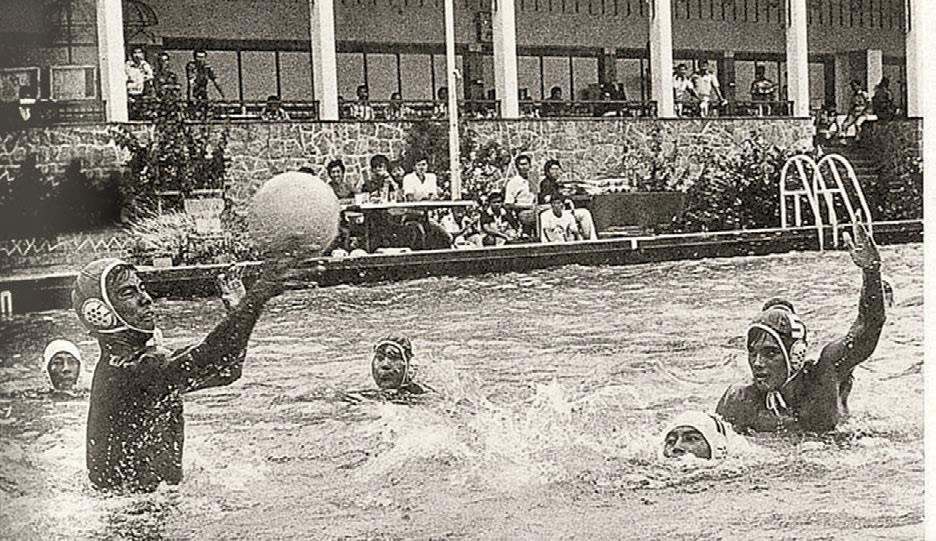

The NCOs were a sporty bunch, representing the club in water polo matches, swimming competitions, soccer, badminton and hockey tournaments, and marathons. Courtesy of MINDEF.

The NCOs were a sporty bunch, representing the club in water polo matches, swimming competitions, soccer, badminton and hockey tournaments, and marathons. Courtesy of MINDEF.The government spent $236,000 sprucing up the premises, and on 17 March 1974, the newly refurbished NCO Club was officially opened by Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee. A fancy club in the middle of downtown with an Olympic-sized pool, food and beverage outlets, and recreational facilities was much welcomed by soldiers working in military units scattered in the rural outskirts of Singapore.16

Lim Phai Som, the first president of the club from December 1973 to April 1974, had only five months to get the club ready before the big opening day. After being left derelict for nearly three years, the club was in shambles when renovations began in October 1973. But Lim and his team managed to restore the shine back to the club before it opened.

Truth be told, the facilities of the NCO Club were quite spartan on opening day. Compared to what the British forces had enjoyed at the Britannia Club, the Singapore soldiers were only served by a handful of hawker stalls – selling local fare such as chicken rice, wonton noodles and rojak – a Snack Bar, the Barrel Lounge, Billiards Room, Reading Room and, of course, that magnificent swimming pool. But still, it was a place to call their own – and the downtown location was undeniably superb.

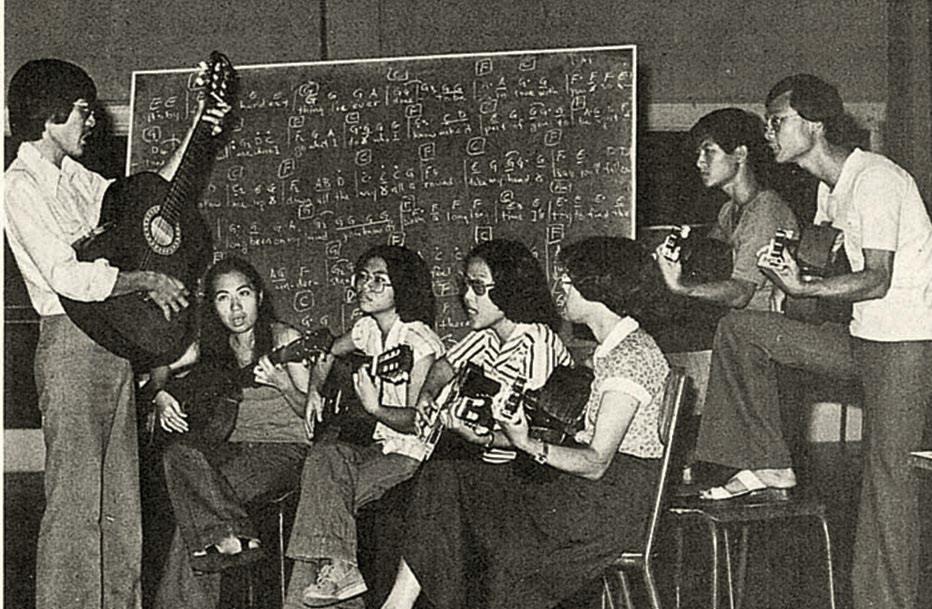

In the 1980s and 90s, the NCO Club organised events such as tombola nights, barbecue nights, Christmas and New Year parties, social dance lessons, music and swimming classes as well as cultural performances for members. Courtesy of MINDEF.

In the 1980s and 90s, the NCO Club organised events such as tombola nights, barbecue nights, Christmas and New Year parties, social dance lessons, music and swimming classes as well as cultural performances for members. Courtesy of MINDEF.Something for Every NCO

It cost the NCOs little to join the club: regulars paid $1 a month in membership dues and their national service counterparts paid 50 cents or $1 depending on their rank.

Ex-national serviceman Aloysius Lim, who stepped into the freshly minted club in April 1974 recalls: “I went like ‘Wow!’. The facilities were first rate and you couldn’t beat the downtown location. Even the senior officers were envious that such a posh facility was given to us lowly NCOs. It was the perfect place to meet up with my army buddies on the weekends. We would have a couple of cheap beers at the Barrel Lounge, walk over to the nearby Satay Club at the Esplanade for dinner and then watch a late-night movie at the old Capitol Theatre in Stamford Road. Everything was within walking distance.”17

Membership numbers, both men and women, grew steadily over the years. By the time the club celebrated its fourth anniversary in March 1978, it already had 25,282 members.

A wide range of activities and courses was organised for NCOs and their families and at heavily subsidised rates. In 1978 for instance, according to the in-house magazine The NCO, the following were offered to members: a 10-session copper tooling course for $15; 12 social dancing classes by “Mr Sunny Low of Poh San Studios fame” for $15; fashion design over 12 sessions by “the talented Mrs Raja from the Adult Education Board”; a 12-session music course for children by “Mrs Koh Teck Lee of the Yamaha Music School”; and eight classes on magic tricks for $10.

More and more enrichment courses were held over the years. By the 1980s, there was everything from sewing and skin care to language classes – Mandarin, Japanese, French – and courses on how to use a computer and basic car maintenance.

Events like tombola nights, barbecue nights, excursions, picnics and cruises throughout the year were well patronised, and Christmas and New Year parties were always a highlight in the calendar. In December 1991 for instance, the New Year’s Eve “Dance Night” only cost $25 per couple – for drinks, entertainment, a lucky draw and door gifts.

Every club anniversary in March would be celebrated with a huge Family Carnival. In the 1980s, quite a few of these took place at the Mitsukoshi Garden in Jurong or Big Splash in the east coast, both sprawling outdoor water theme parks where NCOs and their families would gather for a day of revelry and feasting.

The NCOs were a sporty bunch – representing the club in swimming competitions, soccer, badminton and hockey tournaments, and marathons (or road relays as they were known then) – in addition to being artistically adept. The club’s Indian and Chinese dance troupes had an active calendar of performances. The club members were also a generous lot, organising dinners and outings for senior citizens and disabled children living in homes.18

Over the years, 15 the NCO Club was renovated and upgraded several times. The Barrel Lounge was moved to a different location with a live band providing entertainment; the al fresco hawker stall area by the poolside was converted into a gym; the Cosy Corner started featuring Karaoke Nights in addition to its regular Dance Nights; an air-conditioned cafeteria serving local and Western food was added; a jackpot machine room (called “fruit machines” in a throwback to Singapore’s colonial past) and a video games arcade supplemented the Billiards Room; and a basketball court and multi-purpose hall, the latter for tombola nights and performances, were built.19

But the most ambitious addition to the NCO Club was the value-for-money SAFE Superstore (see text box below) where army, airforce and military personnel could buy groceries and household appliances at bargain prices.

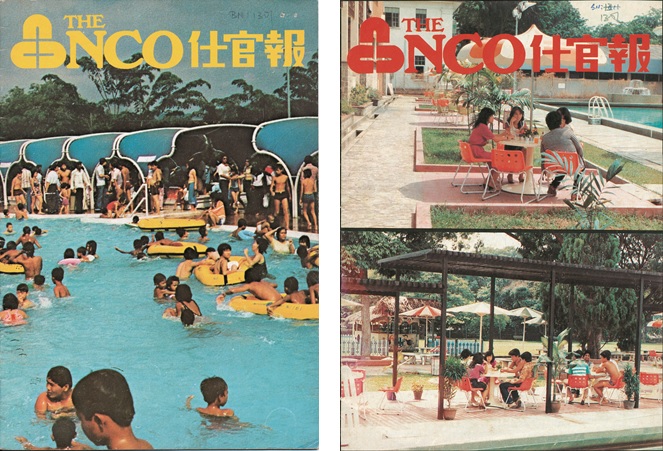

The NCO magazine. Left: May 1980, Vol. 5, No. 1.

Right: Nov 1981, Vol. 6, No. 2. Courtesy of MINDEF.

The NCO magazine. Left: May 1980, Vol. 5, No. 1.

Right: Nov 1981, Vol. 6, No. 2. Courtesy of MINDEF.The End of an Era

Due to restructuring, the term NCO was dropped from the SAF lexicon and changed to Warrant Officers and Specialists on 1 July 1992. Thereafter, the NCO Club was renamed the SAF Warrant Officers and Specialists (WOSE) Club on 22 March 1994, but its functions remained largely the same.20

However, with Beach Road Camp earmarked for redevelopment in the mid- 1990s, it became clear that the occupants of the NCO Club and Beach Road Camp would eventually relocate elsewhere.21

In 2000, the last battalion at Beach Road Camp moved out and a year later, in October 2001, the SAF WOSE Club relocated to a new clubhouse at Boon Lay Way with a new identity. The clubhouse was officially opened on 8 February 2002 by Tony Tan, who was the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence at the time. Its new identity, THE CHEVRONS, signifies the V-shaped stripes worn by all Warrant Officers and Specialists.22

SAFE SUPERMARKET FOR SUPER SAVINGS

In early 1973, Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee mooted the idea of setting up a special shop where SAF personnel and their families could purchase discounted goods such as groceries and electrical items.

The concept was inspired by the so-called PX (or Post Exchange) stores in American military bases, where both active and retired military personnel could buy food and basic household items at marked-down prices. The idea could not have been more welcome in 1973 as Singapore had been battling with runaway inflation triggered by the global oil crisis.

A non-profit business arm of the military was set up called SAF Enterprises, or in short, SAFE. The intention was for these no-frills SAFE stores to pass on the savings accrued from rentfree premises and bulk purchases to military personnel and their families.23

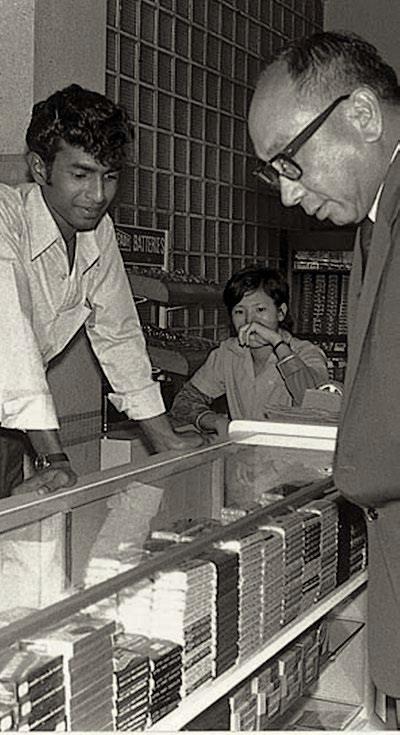

The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) established SAFE supermarkets at the Dempsey Road Camp and NCO Club, selling food and basic household items at discounted prices to military servicemen and their families. The biggest draw was the duty-free beer, which sold at less than half the retail price. Courtesy of MINDEF.

The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) established SAFE supermarkets at the Dempsey Road Camp and NCO Club, selling food and basic household items at discounted prices to military servicemen and their families. The biggest draw was the duty-free beer, which sold at less than half the retail price. Courtesy of MINDEF.

Within months of the announcement, two SAFE supermarkets opened, one at Dempsey Road Camp and the other at the NCO Club. Apart from air-conditioning, the supermarkets had none of the luxuries one would find in an Orchard Road store. SAFE did give the downtown stores a run for their money though – selling groceries, basic furniture like PVC sofas and dining chairs as well as small electrical items like hairdryers and fans at significantly discounted prices.24

Soldiers and their families descended on the supermarkets in droves on the weekends. Snaking queues also formed for the duty-free beer, which sold at less than half the retail price. In the 1970s and 80s, the NCO Club became synonymous with cheap beer.25

Richard Chung, who was a national service guardsman in 1980, recalls having to show his SAF 11-B (the military identity card) before making his purchase: “We bought beer even if we didn’t drink beer. It was that cheap. Some rascals would buy the beer, sell it off to friends and relatives at a higher price and pocket the difference. Of course it was illegal, but who was to know?”26 The SAFE people must have figured this out, which was why each soldier was only allowed to buy one carton a month.

In July 1974, as the oil crisis worsened, the Dempsey Road outlet was opened to all civil servants, but without access to the cheap beer. Over the years, the grocery sales were eclipsed by sales of electrical goods. In the late 1970s, Setron and Grundig television sets, Hotpoint and Acma refrigerators, Singer sewing machines, Akai and Telefunken hi-fi stereo sets – brands that have vanished over the years – were all the rage, and getting these items for that new HDB flat was a much-cherished dream.27

To make the electrical products affordable, SAFE introduced a low-interest credit scheme for public sector employees and military personnel. They only had to agree to pay a small initial downpayment and the balance in 12, 18 or 24 instalments, and they could cart home a brand new 24-inch Grundig colour television set from Germany.

In 1977, the SAFE supermarket in Dempsey closed, and the outlet at the NCO Club was rebranded as SAFE Centre, stopping its sales of groceries altogether to focus on electrical goods and furniture.

In the early 1980s, SAFE closed its NCO Club store and opened a SAFE Centre in Chin Swee Road. The company would eventually be sold and renamed SAFE Superstore in 1989, expanding perhaps too quickly over the years before it went out of business in 2003.28

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee visits the SAF Enterprises (SAFE) supermarket at the NCO Club during its official opening on 20 December 1973. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee visits the SAF Enterprises (SAFE) supermarket at the NCO Club during its official opening on 20 December 1973. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This is an abridged version of the chapter “1854–2001: History of Beach Road Camp and NCO Club” from the book South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road by Francis Dorai and published by Editions Didier Millet for South Beach Consortium in 2012. The South Beach development, designed by the British architecture firm Foster + Partners, was launched in December 2015 and comprises a luxury hotel, offices, apartments and retail space.

Francis Dorai has worked for over two decades in publishing, both as writer and editor in a broad range of media, including The Straits Times, Insight Guides, Berlitz Publishing, Pearson Professional, Financial Times Business and Editions Didier Millet. He is the author of several books, including South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road.

Francis Dorai has worked for over two decades in publishing, both as writer and editor in a broad range of media, including The Straits Times, Insight Guides, Berlitz Publishing, Pearson Professional, Financial Times Business and Editions Didier Millet. He is the author of several books, including South Beach: From Sea to Sky: The Evolution of Beach Road.

Notes

-

The history of the SVC was featured in the article “Beach Road Camp and the Singapore Volunteer Corps”, which appeared in Vol 12, Issue 2 (July–October 2016) of BiblioAsia magazine. ↩

-

Yue, R. (1952, December 17). Million dollar club house to open today. The Singapore Free Press, p. 1; Yue, R. (1952, December 17). It’s one of the nicest clubs in the East. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Britannia Club for public use. (1973, April 28). New Nation, p. 6; HDB to give reservists preference. (1974, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press , 17 Dec 1952, p. 1; The Singapore Free Press, 17 Dec 1962, p. 2. ↩

-

Shackle Club opened. (1947, July 3). The Straits Times, p. 7; New centre for troops: Work starts on new Forces club. (1951, July 10). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nuffield pool may be ready in June. (1951, April 6). The Straits Times, p. 4; ‘A boon’ to the forces. (1951, December 20). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press , 17 Dec 1962, p. 2. ↩

-

Beauty show for the troops. (1953, May 16). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Interview with Carol Traynor. ↩

-

Interview with John Harper. ↩

-

Forces look for a pin-up girl. (1956, February 20). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Commons defence debate: The decision to pull out is final. (1967, July 29). The Straits Times, p. 6; All out by 1971. (1968, January 17). The Straits Times, p. 1; Campbell, W. (1971, October 30). Pull-out. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Naval Base – big town with a civilian future. (1968, July 8). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Future of closed down Britannia Club being discussed. (1971, October 29). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chin, U.W., & Yeo, J. (Eds.). (2015). The Chevrons celebrates: Our journey, our vision. Singapore, p. 9. Retrieved from The Chevrons website. ↩

-

HDB to give reservists preference. (1974, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Interview with Aloysius Lim. ↩

-

Chin & Yeo, 2015, pp. 12, 14. ↩

-

Chin & Yeo, 2015, pp. 11, 13. ↩

-

Chin & Yeo, 2015, p. 15; The SAF Warrant Officers and Specialists Club. (2002). The Chevrons: Forging closer ties (p. 7). Singapore: Author, Call no.: RSING 355.346095957 CHE ↩

-

Yap, E., (1996, April 14). Not quite the Golden Mile but there’s hope. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chin & Yeo, 2015, pp. 18, 20; DPM Tan stresses need to maintain harmony. (2002, February 9). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cheang, C. (1973, December 21). Joint effort food firm to curb inflation…The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Super-mart opens its doors to govt staff. (1974, July 29). The Straits Times, p. 13; From humble army stores to award-winner. (1996, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 27 Apr 1996, p. 2. ↩

-

Interview with Richard Chung. ↩

-

Civilians make full use of SAFE. (1974, July 31). New Nation, p. 2; The Straits Times, 27 Apr 1996, p. 2. ↩

-

The Straits Times , 27 Apr 1996, p. 2. ↩