Ties that Bind: The Story of Two Brother Poets

An American Studies scholar unravels a decades-old mystery surrounding a bone fragment and uncovers a brotherly bond from beyond the grave. Michelle Heng has the story.

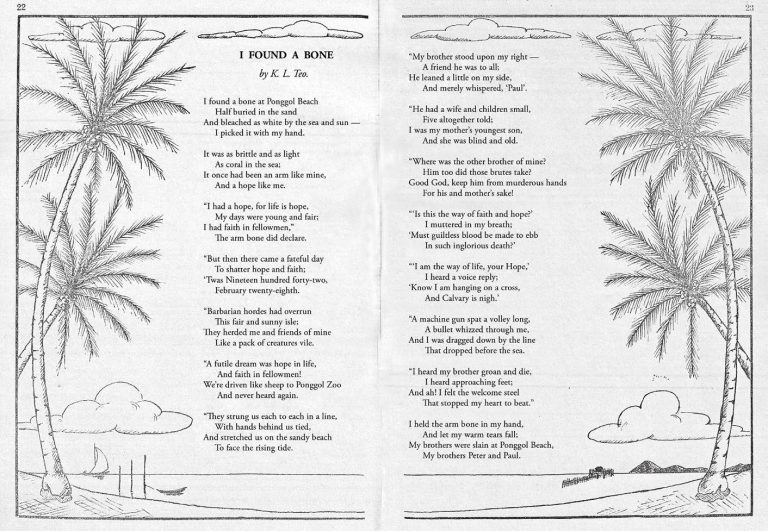

And let my warm tears fall;

My brothers were slain at Ponggol Beach,

My brothers Peter and Paul.”

Excerpt from “I Found A Bone”

by Teo Kah Leng

When American Studies scholar, Dr Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, embarked on the proverbial journey of a thousand miles to find out all she could about the elusive poet behind F.M.S.R.1 – widely acknowledged as one of the first notable works of English poetry by a Singaporean writer – little did she suspect that her research would unravel the mystery of not just one but two long-forgotten poets.

Ultimately, this would set in motion a chain of events that would turn the dregs of a family’s painful war-torn past into a serendipitous “reunion” of two talented brother-poets2 and the publication of two unique collections of poetic works.

The Search Begins

Dr Ogihara-Schuck, a Japanese national who teaches American Studies and Japanese at Technische Universität Dortmund in Germany where she resides with her German husband, first chanced upon F.M.S.R.3 when she answered a call in December 2012 for academic papers by the late Professor Tatsushi Narita, a specialist on the works of the Anglo-American modernist poet T.S. Eliot.4

On perusing F.M.S.R. at the British Library, she was intrigued how this 10-part poetic narrative about a train journey from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur on the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR) took inspiration from T.S. Eliot’s seminal work, The Waste Land,5 using it as a literary vehicle to call for the advancement of Malayan modernism.6

Her initial idea to turn to Japan for her research was shelved upon discovering that much ground on the Japanese reception of T.S. Eliot had already been covered.7 So she turned to the literary works of her “second home”, Singapore – where she had spent her teenage years from 1988 to 1994 when her father, a former Panasonic employee, was based there.

Her interest in republishing F.M.S.R. and making it available to the public grew. However, the endeavour was fraught with problems from the very start as F.M.S.R. was an “orphan work”, and republishing it would not be possible unless its copyright status could be verified. No biographical information about the author, Francis P. Ng, could be found and the premises of the book’s London publisher had been bombed during World War II.

On probing further, Ogihara-Schuck unexpectedly discovered that “Francis P. Ng” was actually a pseudonym8 and that the poet’s real name was Paul Teo Poh Leng, a primary school teacher who was born in Singapore in 1912. She found this vital piece of information in “The Song of the Night Express”, the seventh section of F.M.S.R. that had been published separately as a poem in the Spring 1937 issue of the British literary journal, Life and Letters To-day.9

This breakthrough discovery of the poet’s real identity enabled Ogihara-Schuck to gather further information about the author while working at her desk in Germany. Tapping the National Library Board’s online resource, NewspaperSG, she found quite a few newspaper articles with his name.

Help also came from several other sources. Tim Yap Fuan, the Associate University Librarian at the National University of Singapore, tracked down Teo Poh Leng’s essays that had appeared in the Raffles College Union Magazine (Teo was a student of the college between 1931 and 1933); and the University of Chicago’s archives shared with her a letter that Teo had sent to an American poetry magazine in 1931. But no further details of Teo could be traced following the publication of his last essay in the Raffles College Union Magazine in 1941.

Undaunted, Ogihara-Schuck flew to Singapore in the summer of 2014 to do further research. The full details of her astonishing discovery are documented in the article “On the Trail of Francis P. Ng: Author of F.M.S.R.” in Vol. 10 Issue 4 (Jan–Mar 2015) of BiblioAsia, the quarterly journal published by the National Library, Singapore.10

What happened subsequently is the stuff of detective fiction novels. Journalist Akshita Nanda picked up on the BiblioAsia article, contacted Ogihara-Schuck and followed up with a report on the Japanese academic’s search for a pioneering Singaporean poet who had disappeared during World War II. The article, published in The Straits Times on 22 February 201511 would ultimately lead to a series of startling discoveries and, eventually, a touching family reunion.

The Brother-Poets

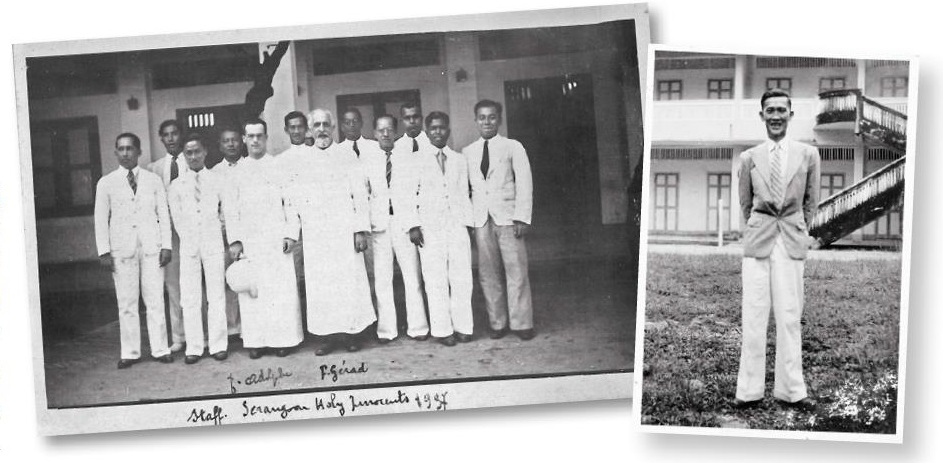

The Straits Times’ article headlined “Do you know Teo Poh Leng?” jogged the memory of a reader by the name of Samuel Chia. He contacted the reporter to tell her about his childhood recollection of a poem titled “I Found A Bone”, penned by a poet named Teo Kah Leng, then a teacher at the Holy Innocents’ English School. Chia had correctly guessed that Poh Leng was Kah Leng’s brother due to the similarity of their names. He further suspected that Poh Leng was one of the two brothers, “Peter and Paul” mentioned in the final line of “I Found A Bone”, who had died during the Japanese Occupation.

Peter was the Christian name of Teo Kee Leng, the elder brother, while Poh Leng (whose Christian name was Paul) was the youngest sibling. Kah Leng himself had escaped the same fate because he was not at home when his brothers were hauled away by the Japanese soldiers.

Chia, a former pupil at St Gabriel’s School, which was then a sister-school of the Holy Innocents’ English School, was too young to read the entire poem but he recalled being drawn to “I Found A Bone” because it was accompanied by an attractive illustration of a tranquil landscape with coconut trees framing a beach. The poem, with the drawing, was published in the 1955 issue of the Holy Innocents’ English School Annual.12

Chia had asked his sister to read the poem for him – its memorable themes of loss and despair in a war-ravaged Singapore touched him deeply – and etched in his mind both the poem and its poet for the next few decades.

The haunting poem about a man who found his brother’s arm bone fragment at Punggol beach was one of the few clues linking Teo Kah Leng and Teo Poh Leng as brothers. Sadly, it also confirmed the latter’s death during the Sook Ching massacre at the onset of the Japanese Occupation – Punggol beach was one of the sites where Chinese men had been slain by Japanese soldiers.13

This was something that Ogihara- Schuck had earlier surmised; all traces of Teo Poh Leng seemed to have vanished after the fall of Singapore in 1942. As an English-speaking teacher, Teo Poh Leng was most likely a target of the Sook Ching, which saw many thousands of Chinese males being executed for their perceived anti-Japanese stance.14

When Ogihara-Schuck was told about the provenance of the poem “I Found A Bone” and the possible connection between the two Teos, she knew she was on the brink of making a new discovery. She was already aware that Teo Poh Leng’s Christian first name was Paul, and had deduced that “the Chinese names Poh Leng and Kah Leng sounded like a pair of siblings’ names”.15 “I Found A Bone” contained another clue to the hitherto missing piece of the puzzle: the poem included the fateful date, 28 February 1942, when Teo Poh Leng was taken away by the Japanese.

Meanwhile another person was similarly piqued by The Straits Times’ article. This was Anne Teo, the daughter of Teo Kah Leng. Her father had died in 2001 at the age of 92. Who was this Japanese researcher trying to track down her uncle? She contacted Ogihara-Schuck and provided confirmation that Teo Poh Leng was indeed her uncle and that he had fallen victim to the Sook Ching massacre. As Anne had been born after her uncle’s death, she could only recall hearing about Uncle Poh Leng from her father and relatives. Although unaware of his work as a poet, she somehow instinctively knew that “Francis P. Ng” was her uncle when she read F.M.S.R.

Aside from being privy to the fact that “Francis” was Poh Leng’s Christian middle name and “Ng” was his mother’s surname, the imagery of the Serangoon area portrayed in F.M.S.R. sounded familiar to Anne as she had grown up in that district.

Finding Francis is Published

On learning of Ogihara-Schuck’s plans to republish F.M.S.R, Anne Teo proposed a collaboration with her on the project. She also provided the much needed confirmation that her uncle had been dead for more than 70 years, which meant that copyright for the book had expired and now resided in the public domain.

Another person who played a significant role in this journey was the Singaporean poet and literary activist, Alvin Pang, who had been aware of F.M.S.R. more than a decade before Ogihara-Schuck began researching it. After being introduced to the original 1937 edition of F.M.S.R. – one of five extant copies available in the world – by former librarian Yenping Yeo of the National Library, Singapore, in the early 2000s, Pang approached several Singapore institutions in the hope of creating awareness of this long-forgotten poem.

Thus, when Ogihara-Schuck fortuitously turned to Pang for advice on the republishing of F.M.S.R., he introduced her to Fong Hoe Fang, the founder of Ethos Books. Fong too was similarly enthused by the discovery of this lost poet “who was published on the same platform with writers like Robert Frost and W.B. Yeats”, and under his guidance, Finding Francis: A Poetic Adventure, was published in October 2015.16

Finding Francis is indeed an apt title for this volume of Teo Poh Leng’s works, reflecting the painstaking two-and-a half-year mission that began in February 2013 and saw Ogihara-Schuck crossing the globe from Germany to London and to Singapore in her bid to unravel a thread in Singapore’s literary history. What is even more fascinating is that an obscure early 20th-century Singaporean poet could have captured and engaged the imagination of a foreigner such as Ogihara-Schuck – an American Studies scholar of Japanese descent who lives in Germany. Her only link to Singapore was the six years she spent as a teenager in Singapore.

For Ogihara-Schuck, the most serendipitous part of her project was the discovery of another pioneer Singaporean poet –Teo Kah Leng – and the unpublished manuscript of some 50 poems that his daughter Anne had inherited upon his death in 2001. A year after publishing Finding Francis, Ogihara-Schuck and Anne launched Teo Kah Leng’s poetry collection, I Found A Bone and Other Poems in August 2016, with Ethos Books and the aid of a grant from the National Arts Council.

The Redemptive Power of Poetry

For Anne Teo, the discovery of her late uncle and his published poems was proof that her father and his brother were bound by their mutual love for verse.17 Juxtaposing her father’s poems with that of her uncle’s, she suggests that their brotherly bonds rose above the tragedy of war and the Japanese Occupation through the redemptive power of forgiveness, as seen in the poem “I Found A Bone”.18

There are enough Christian motifs in the poem to suggest this idea. It starts and ends with Teo Kah Leng’s voice but switches to the persona of his younger sibling, Teo Poh Leng, in stanzas 12 and 13 as he recounts his tragic death at Punggol beach: “I am the way of life, your Hope… / Know I am hanging on a cross / And Calvary is nigh.”

Although Teo Kah Leng lost his two beloved siblings in the war and was suddenly thrust with the financial and moral responsibility of looking after his extended families, Anne says that her father was able to “help Uncle Poh Leng remain a poet even after his death” by literally immortalising him in “I Found A Bone”.

Indeed, some of Teo Poh Leng’s poetry seemed to uncannily portend future tragic war events even before he fell victim. “Uncle Poh Leng seemed to have believed in the importance of forgiveness,” she adds.19 Anne highlights Poh Leng’s poem “Time Is Past” as an ode to forgiving past transgressions and moving on: “Time its neck no more holds me in case. / Time is past: / I move upon an earthless plane, / At last!”

Reflecting on the grim events that had cast a pall over her father’s youth and the remainder of his life following the Japanese surrender, Anne says that even though her father’s “yoke was heavily laden with misery, despair, and sorrow… he chose to exercise his right to be ‘free’ by forgiving the perpetrators”. She draws attention to her father’s poem “The Cicada”, in which he penned these lines: “The past is gone. Let it be dead! / Call not to life its phantoms dread / With fearful shrieks and tearful cries.”20

For Ogihara-Schuck, her quest to uncover the life of Teo Poh Leng magnified the “feel” of his powerful verses. In an email, she revealed how she was emotionally affected by the untimely end of Teo Poh Leng, whose promising career as a poet, along with whatever hopes and dreams he had, was shattered by the Sook Ching. “It was really painful to read articles about Raffles College students (including Poh Leng) graduating from college and looking forward to their future while not knowing what was going to happen to them some years later.”21

Ogihara-Schuck was wistful when she came across a list of Sook Ching victims containing their names, ages and addresses. The knowledge that so many in Singapore had suffered at the hands of the Japanese must have been an uncomfortable memory.

She reveals: “I could recognise some of the addresses, so I ‘felt’ the reality of the experience. It was the same feeling I had when I saw the list of Jewish victims of the Holocaust at the school where my husband teaches. As part of a school project, the students had researched on former Jewish pupils at their school who had been sent to concentration camps.”22

In a fitting denouement of the transcendental power of the brother-poets’ works, Anne writes in the concluding essay of Finding Francis that “through their poems, the brother-poets sought to unshackle themselves from a dreaded past through forgiveness, to foster hope in their lives. As Dad wrote in “I Found A Bone”, taking on the voice of his brother, ‘life is hope’”.23

The personal lives of the two brotherpoets and the Christian concept of forgiveness and redemption articulated in Kah Leng’s “I Found A Bone” – despite its tragic ending – is an expression of that hope.

Michelle Heng is a Literary Arts Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She has curated a tribute showcase, "Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition" in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo, Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

Michelle Heng is a Literary Arts Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She has curated a tribute showcase, "Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition" in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo, Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

Notes

-

F.M.S.R. was published in 1937 by the London publisher, Arthur H. Stockwell. See Toh, H. M (2007). Introduction to Singapore poetry on Ars Interpres. Retrieved from Ars Interpres website; Pang, A., & Shankar, R. (Eds.). (2015). Editors’ introduction. In Union:15 years of drunken boat, 50 years of writing from Singapore (pp. 12–13). Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 UNI ↩

-

Teo, A. (2015). Conclusion (p. 55). In E. Ogihara-Schuck & A. Teo. (Eds.), Finding Francis: A poetic adventure. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 NG ↩

-

Ng, F.P. (1937). F.M.S.R.: A poem. London: Arthur H. Stockwell. Call no.: RCLOS 821.9 PNG-[FRL] ↩

-

Tatsushi Narita was looking for participants in his panel discussion titled “T.S. Eliot: East and West” but passed away before the conference convened. Although she had never met Narita in person, Ogihara-Schuck attributes the start of her research on F.M.S.R. to his last research effort before his death. Ogihara-Schuck’s paper was presented at the International Association of American Studies (IASA) conference in Poland in 2013. ↩

-

Holden, P. (2009). Introduction: Literature in English in Singapore before 1965 (p. 10). In A. Poon, P. Holden & S. G-L. Lim. (Eds.), Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press; National Arts Council Singapore. Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E. (2015). Introduction (pp. 8–32). In E. Ogihara-Schuck & A. Teo. (Eds.), Finding Francis: A poetic adventure. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 NG ↩

-

Personal email communication with Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, 2016. ↩

-

Only much later did Ogihara-Schuck discover the origins of the pseudonym Francis P. Ng – a combination of Teo Poh Leng’s first and middle Christian names, Paul Francis, but in reverse order, and his maternal family name, Ng. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1937). The song of the night express. Life and Letters To-day, 16 (7), 44. Not available in NLB holdings. ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E. (2015, Jan-Mar). On the trail of Francis P. Ng: Author of F.M.S.R. BiblioAsia, 10 (4), 38–45. Call no.: RSING 027.495957 SNBBA-[LIB] ↩

-

Nanda, A. (2015, February 22). Do you know Teo Poh Leng? The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E. (2016). Editors’ introduction (pp. 6–8). In K.L. Teo, I found a bone and other poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 TEO ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E., & Teo, A. (Eds.). (2015). Acknowledgements (pp. 4–5). In F. Ng & K.L. Teo, Finding Francis: A poetic adventure. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 NG; Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan years: Singapore under Japanese rule 1942–1945 (pp. 113–115). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram Pte Ltd. Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]; “Chinese massacre” Japs hanged at Changi. (1947, June 26). Malaya Tribune, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, S., et al. (2009). Syonan Years, 1942-1945: Living beneath the rising sun (p. 14). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. Call no.: RSING 940.530745957 TAN-[WAR]; Akashi, Y. (1970, September). Japanese policy towards the Malayan Chinese, 1941–1945. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1(2), 61–89, p. 67. Call no.: RSING 959.005 JSA ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E. (2016). Editors’ introduction (pp. 6–8). In K.L. Teo, I found a bone and other poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 TEO ↩

-

Nanda, A. (2015, October 12). Work of lost Malayan poet Teo Poh Leng republished after 78 years thanks to ST article. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Teo, A. (2015). Conclusion (p. 55). In E. Ogihara-Schuck & A. Teo. (Eds.), Finding Francis: A poetic adventure. Singapore: Ethos Books. Call no.: RSING S821 NG ↩

-

Personal email communication with Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, 2016. ↩

-

Personal email communication with Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, 2016. ↩