Gedung Kuning: Memories of a Malay Childhood

Gedung Kuning, or the “Yellow Mansion”, was once the home of Tengku Mahmud, a Malay prince. Hidayah Amin shares anecdotes from her childhood years growing up in the house.

Haji Yusoff posing proudly with his classic Austin Six at the entrance of Gedung Kuning in 1939. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

Haji Yusoff posing proudly with his classic Austin Six at the entrance of Gedung Kuning in 1939. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.Gedung Kuning1, at No. 73 Sultan Gate, with its regal yellow walls and stone eagles perched on the main gate, was the mansion that was originally built for a bendahara or prime minister. When I was growing up in the house, I never once thought of my family as being privileged or different in any way. When the government acquired my childhood home in 1999, it began to dawn on me that having been born in Gedung Kuning and raised in Haji Yusoff’s family, I was part of an important heritage.

Haji Yusoff bin Haji Mohamed Noor was my moyang, or maternal great-grandfather, and the patriarch of Gedung Kuning, having bought the mansion in 1912. As he had passed on before I was born, I never had the opportunity to meet the man with his sharp nose, white moustache and gentle eyes that seemed to gaze directly into mine every time I passed by his portrait in the living room.

A 1930s painted portrait of the author’s maternal great-grandfather, Haji Yusoff bin Haji Mohamed Noor, wearing a songkok, a traditional cap made of velvet worn by Malay men, and a Western-style jacket. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

A 1930s painted portrait of the author’s maternal great-grandfather, Haji Yusoff bin Haji Mohamed Noor, wearing a songkok, a traditional cap made of velvet worn by Malay men, and a Western-style jacket. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.Haji Yusoff was a man who loved his family only second to God. He was a respected merchant who later became a pillar of the Malay community in early Singapore. Gedung Kuning is as regal as its name and owner – a testament to Haji Yusoff’s legacy – and I am proud to share his legacy with you. Here are two extracts from my book, Gedung Kuning: Memories of a Malay Childhood.

No. 73 Sultan Gate

Rumahku, syurgaku, my house, my paradise. To many of us, the home is definitely where the heart is and Gedung Kuning, at No. 73 Sultan Gate, Kampong Glam, was such a home to four generations of the Haji Yusoff family. Built in the mid-19th century, Gedung Kuning was once the home of a prince – Tengku Mahmud – grandson of Sultan Hussein of Johor with whom Sir Stamford Raffles of the East India Company negotiated a treaty to establish a trading post on Singapore island back in 1819, thus setting in motion events that would lead to the creation of modern-day Singapore.

Gedung Kuning was, and remains, a grand and stately affair, symmetrical in plan with classical detailing in the Anglo- Regency style of architecture that the British brought with them from India. Apart from the Istana next door, there is no other building like it in Kampong Glam. Rumour has it that the Istana and Gedung Kuning were designed by George Coleman, Singapore’s first and, for many years, its finest architect, famous for the palatial mansions he designed for rich merchants and government officials in the early days of the settlement. Although this has never been substantiated, the two buildings certainly show evidence of his influence.

It was Tengku Mahmud who painted the house yellow – the colour of royalty in traditional Malay society – which is how it came by its name, Gedung Kuning (literally “Yellow Mansion”). But family fortunes change and Tengku Mahmud’s father, Sultan Ali, mortgaged the house to an Indian moneylender to pay his debts. This was around the end of the 19th century and it is here that my story properly begins.

As a boy growing up in his father’s house in the vicinity of today’s Kandahar Street, Haji Yusoff would have passed by Gedung Kuning every day, no doubt looking up in awe at the majestic mansion. Later, in adult life, when he learned that Gedung Kuning was mortgaged to an Indian moneylender, he must have been disappointed at how easily the Malay royal family “gave” away a significant piece of their history to people regarded locally as “foreigners”.

An industrious young man on the way up in life with dreams, Haji Yusoff strongly felt that Gedung Kuning should return to the Malay community. At the same time, he needed to provide a home for his second wife and her children, and so he decided he would spend his entire savings to purchase Gedung Kuning. My grandmother, Nenek, who was Haji Yusoff’s eldest daughter, said he paid about $37,000 in cash, a huge amount in those days, to R.M.P.C Mootiah Chitty in 1912.

Haji Yusoff’s family posing in front of Gedung Kuning for a family gathering in 1958. Hajah Aisah (Haji Yusoff’s second wife and Hidayah Amin’s great-grandmother) is seated 6th from the right. On her right is Nenek, Hidayah’s grandmother, while her mother Emak is seated 4th from the right. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

Haji Yusoff’s family posing in front of Gedung Kuning for a family gathering in 1958. Hajah Aisah (Haji Yusoff’s second wife and Hidayah Amin’s great-grandmother) is seated 6th from the right. On her right is Nenek, Hidayah’s grandmother, while her mother Emak is seated 4th from the right. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.Unfortunately, some years later, needing to raise capital for his business, Haji Yusoff was obliged to sell the house to a Chinese family. This was in 1919. Subsequently, Gedung Kuning was sold to another Chinese family. According to rumours, neither Chinese family took to living at Gedung Kuning. In fact, one occupant is said to have turned insane while another committed suicide. When the father of one of the Chinese owners passed away while staying in Gedung Kuning, a medium was hired to “cleanse” the house of its misfortune, but this was not enough to dispel the idea that the house was “unlucky” and it was put back on the market again.

Thus it was that Haji Yusoff, who had always regretted his decision selling Gedung Kuning, suddenly found himself in a position to buy it back six years later. The Chinese owner, however, refused to sell the house to Haji Yusoff whom he chided as a poor Malay man. Being the astute businessman that he was, Haji Yusoff engaged a middleman named Haji Umar “Broker” to negotiate the purchase of the house on his behalf. Haji Umar convinced the Chinese owner that a wealthy “Sultan of Trengganu” was interested in acquiring Gedung Kuning and a deal was struck.

However, when the time came for the supposed “Sultan of Trengganu” to sign the legal papers for the sale of the property, it was Haji Yusoff who turned up instead. Though horrified, the Chinese owner could not back out of the deal, especially when Haji Yusoff offered to seal the transaction immediately in hard cash. It is not known how much Haji Yusoff paid this time around, but it was definitely worth the price since the jubilant Haji Yusoff had retrieved his lost paradise.

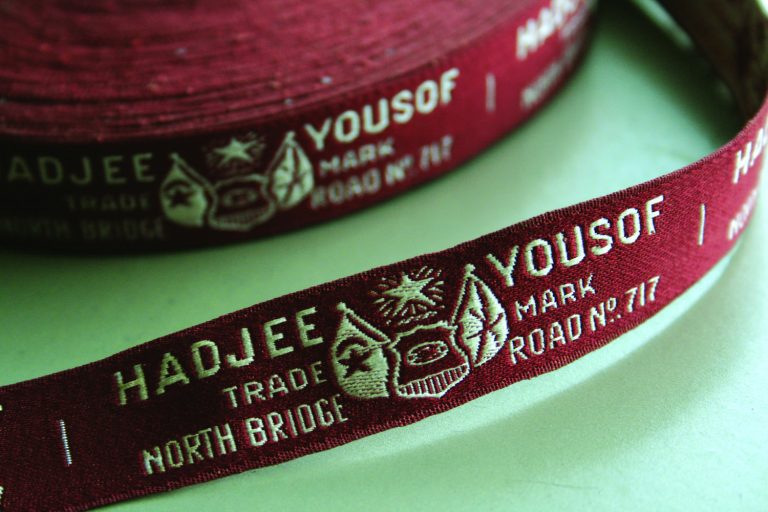

Haji Yusoff’s tali pinggang trademark design comprised a belt buckle flanked by two flags with a shining star above the buckle. The trademark was sewn onto the tali pinggang – a belt with a small money pouch worn by men over their sarong or pants – that he sold in Kampong Glam. The belts were also exported to other countries in the region. Photo by Yeo Wee Han. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

Haji Yusoff’s tali pinggang trademark design comprised a belt buckle flanked by two flags with a shining star above the buckle. The trademark was sewn onto the tali pinggang – a belt with a small money pouch worn by men over their sarong or pants – that he sold in Kampong Glam. The belts were also exported to other countries in the region. Photo by Yeo Wee Han. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.His paradise regained, Haji Yusoff was to live happily at Gedung Kuning for almost 30 years before a stroke in 1948 left him bedridden; he passed away two years later at the age of 95. Though no one could remember what his funeral was like, I presume that many people must have attended the funeral rites to pay respect to one of the pillars of the Malay community – I can imagine how the residents of Kampong Glam mourned the loss of their finest kampong son.

Though I never knew Haji Yusoff personally, through hearing so much about him as a child – he was still very much a part of Gedung Kuning when I was growing up there, in spirit, if not in body – he has always been there as a kind of inspiration and “guiding” presence in my life. The story of Gedung Kuning is as much the story of Haji Yusoff as it is the building itself. Gedung Kuning bore witness to Haji Yusoff’s increasing prosperity, his growing family, and the birth of my aunts and uncles. As home to all of his second wife’s children and their children in turn, at one point in time six household units could be found all living together beneath the one roof. Gedung Kuning was to remain in the family for almost a hundred years and life there was akin to a century of history in the making. Sadly, nearly 50 years after the death of Haji Yusoff, the Gedung Kuning family once again found itself grieving the loss of their paradise when the house was acquired under the Land Acquisition Act and Haji Yusoff’s long legacy came to an end.

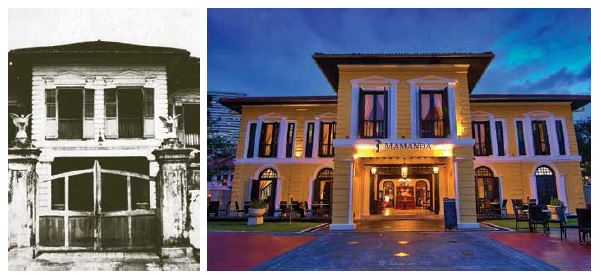

(Left) A photo taken on 2 June 1955 showing the facade of Gedung Kuning at No. 73 Sultan Gate. The rear of the house faces Kandahar Street. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

(Left) A photo taken on 2 June 1955 showing the facade of Gedung Kuning at No. 73 Sultan Gate. The rear of the house faces Kandahar Street. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.(Right) Gedung Kuning was acquired under the Land Acquisition Act in 1999, and underwent restoration until 2003. Currently housed within the building is the Mamanda restaurant that serves Malay cuisine. Photo by Erwin Soo, 27 October 2012. Courtesy of Flickr.

Today, although the outer walls of Gedung Kuning are still painted yellow (albeit a darker shade than in the past), I sense that the vibrancy this place once exuded has been lost, its vitality diminished. No longer home to a family that once filled its immense space with great warmth, joy and laughter, Gedung Kuning, personified, misses its former occupants who so epitomised the heart and soul of old Kampong Glam in days gone by.

Puasa and Hari Raya

One of the major festive celebrations at Gedung Kuning was Hari Raya Puasa (Eid ul-Fitri), which marks the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. I remember how as children, we were taught to fast when we were as young as six or seven years old. We began by fasting for just one hour each day, slowly increasing the duration as we grew older. By the time we reached puberty, we could fast from sunrise to sunset, forgoing food and drink for about 12 hours daily. Fasting was such a big deal for us kids. Fasting made us feel grown-up.

Wak Lah [my uncle, Abdullah] used to tell me how Haji Yusoff emphasised the importance of fasting and prayers to his grandchildren. The strict Haji Yusoff, who attended the Sultan Mosque daily, sometimes splashed water on his grandchildren to wake them up for morning prayers.

Since the girls of Gedung Kuning were more obedient, they were never given the “water treatment”. Sometimes, Haji Yusoff used his walking stick to tap the legs of the sleeping boys to wake them up. He had a strict ruling during Ramadan; the grandchildren who did not fast could not sit at the dining table with the rest of the family. Forgoing a seat at the long table full of delicious food and dessert was indeed a tragedy. So every child at Gedung Kuning attempted to fast, even if it was for only 30 minutes a day.

I particularly disliked waking up before dawn for the sahur, the early morning meal, eaten just before fasting begins for the day. Emak [my mother] and Nenek [my grandmother] would gently shake my lethargic body but I would always mumble, “five more minutes…” They would finally give up and go downstairs to eat. I would only run down about 20 minutes before sunrise to eat whatever food was left. I remember telling them that I preferred to eat before going to bed and not having to wake up so early in the morning. But of course, as I grew older, I realised the reasons for the sahur meal and changed my eating patterns during Ramadan accordingly.

Ramadan was not complete without the daily trips to the Sultan Mosque to collect bubur masjid (mosque porridge). Almost all the mosques in Singapore prepared the porridge which they gave out freely to the public. I remember queuing with Wak Lah, bringing two plastic containers for the helper at the mosque to fill up with delicious porridge. The bubur was so popular that if you did not queue up early, you might not be able to get it. The simple porridge of rice, little morsels of meat and nuts, was so tasty that sometimes non-Muslims would also stand in queue. In the queue were people from all walks of life. Some of them looked rather poor and the bubur was probably their only meal for the day. I remember when I was preparing food at a homeless shelter in Washington D.C., I thought of bubur masjid. How good it would be if we could serve bubur masjid during other months as well!

Our next destination after collecting bubur at the Sultan Mosque was Bussorah Street, the street leading up to the front of the mosque. The street was lined with shophouses facing each other, in front of which were makeshift tents, sheltering long tables. On these tables was laid out a mouth-watering display of a variety of Malay dishes and desserts to entice passers-by.

Residents of Kampong Glam as well as those from other parts of Singapore made their way each year to the annual Ramadan Bazaar to soak up the festive atmosphere as well as to sample the delicious food. Datuk, my grandfather, would give me some money to spend at the bazaar. It was difficult to choose which food to buy with a small budget so I usually opted for my favourite food, otak-otak, a kind of fish paste mixed with spices such as lemongrass and turmeric, soused in coconut milk and then wrapped in a banana leaf that had been softened by steaming. To drink, I would have air katira. Ahh… who could forget air katira? Made from milk, biji selasih (basil seeds), dates and cincau (grass jelly), it was light green and, for me, could rival any soft drink!

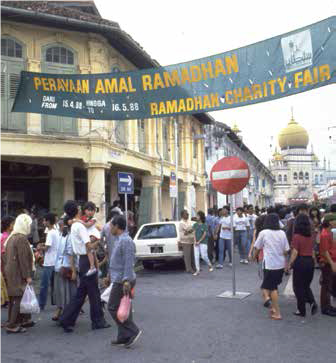

The Ramadan Charity Fair along Jalan Sultan and Bussorah Street in 1988. Sultan Mosque is in the background. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Ramadan Charity Fair along Jalan Sultan and Bussorah Street in 1988. Sultan Mosque is in the background. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.I also remember how my brother Hadi and I were often asked to take some food to other members of the family living at Gedung Kuning, about an hour before we broke our fast. These food exchanges happened more frequently during Ramadan, a time for reflection and sharing. It could be a vegetable or meat dish, or a plate of kuih-muih (cakes), or whatever food that Nenek and Emak cooked. Although we never expected reciprocity, the receiving party would invariably return our plate with food that had been prepared or bought. So you can imagine how much food we ate when we broke fast at around seven in the evening!

About 10 minutes before Maghrib prayers (the evening prayer following sunset), Hadi and I would run up the wooden staircase and look out the window at the end of the landing. From the open windows, we could see the minaret of the Sultan Mosque. We would wait in anticipation as we stared at the little crescent and star at the top of the minaret. During Ramadan, the crescent and star would light up when the muezzin called out the azan (prayer call). Hadi and I would be overjoyed and shout “Dah bang!” (It’s prayer time!). We would then rush downstairs, much to Emak’s unhappiness. “Nanti gelundung!” (You’ll fall headlong) she would say.

Hidayah Amin celebrating her first birthday at Gedung Kuning in 1973. In the photo are four generations of Haji Yusoff’s family. From the left: Hidayah’s grandmother, her great-grandmother and her father. The boy is a cousin of Hidayah’s mother, while the girl is a guest. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

Hidayah Amin celebrating her first birthday at Gedung Kuning in 1973. In the photo are four generations of Haji Yusoff’s family. From the left: Hidayah’s grandmother, her great-grandmother and her father. The boy is a cousin of Hidayah’s mother, while the girl is a guest. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.How we loved Ramadan, especially when it was time for iftar, the evening meal which brings to an end the daily fast. Although we were encouraged to break our fast with something sweet like a kurma (date), Hadi and I would look at the most enticing dish and eat that first. Most of the family members would try to make it home for buka puasa (breaking the fast); no matter how busy one is, one should try to spend dinner time with the family during Ramadan. Ramadan indirectly encourages family togetherness and the spirit of good deeds and kindness. Emak’s cousins at Gedung Kuning would sometimes invite their friends to the iftar meal. I recall how Abah [my father] once brought home a poor stranger and asked him to have a meal with us.

I also remember Datuk leaving the table after eating his dates and drinking his coffee. He would head to the Sultan Mosque for Maghrib prayers, sometimes together with the other male members of the family living at Gedung Kuning. The rest of us would finish eating before praying, but we would leave some food for others like Datuk, who resumed eating after prayers. At times, the women of Gedung Kuning joined the men in the special prayers called terawih, which are held in mosques every night of Ramadan.

During Ramadan, the Gedung Kuning household would be abuzz with activities particularly when the festival of Eid, which brings the fasting season to a close, was nearing. Everyone would lend a hand to give the house an especially thorough cleaning (though there were helpers for the daily cleaning). Nenek was tasked to sew curtains for the whole house.

Each household would tidy up their own living areas, and make cakes and dishes for the upcoming celebrations. They would also buy or sew new baju kurung (Malay traditional costume) for themselves and their children. Everyone would be busy. I recall how Emak painstakingly “pinched” the pineapple tart dough with a cookie pincher to make the patterns, instead of using the cookie cutter. Such a labour of love! Homemade cookies definitely taste better than the store-bought ones which dominate the dessert scene nowadays.

Emak and Nenek would spend the day before Eid cooking, among other dishes, the family favourite, sambal goreng pengantin, a spicy dish of meat and prawns. Nenek mentioned that Haji Yusoff used to keep turkeys on the grounds of Gedung Kuning. He would ask his cook to slaughter the turkeys during festive occasions so that everyone could savour the delicious meat.

No Hari Raya celebrations would be complete without ketupat – boiled rice which has been wrapped in a woven palm leaf pouch – and lontong (rice cakes). Wak Lah would buy them at the famous Pasar Geylang market and he would hang a bunch of ketupat over a long wooden pole laid horizontally between two chairs. When asked, he said it was to prevent them from becoming basi or stale. Everyone was in high spirits and the festive mood was enhanced by traditional Hari Raya songs blaring from the radio which evoked a sense of nostalgia for times past.

I remember waking up on the morning of Eid and hearing the takbir – the chanting proclaiming the greatness of God – coming distantly from the Sultan Mosque. Even when I was celebrating Eid overseas, the takbir never failed to bring tears to my eyes. I liked watching the throng of Malay males making their way past our house to the Sultan mosque (most females in Singapore preferred to stay at home to prepare the Eid meal). They would be clad in their finest baju Melayu, a long-sleeved shirt with a standing collar sewn in a style called cekak musang, with matching trousers and over the top, a length of cloth called the kain samping, woven from silk and gold thread, which was worn like a short sarong. A sea of blues, reds, greens and other bright colours dominated the streets of Kampong Glam. After Eid prayers, the same myriad of colours would embrace each other, asking forgiveness for past transgressions in a spirit of friendship and brotherhood.

Haji Yusoff’s grandchildren celebrating Hari Raya at Gedung Kuning in 1948. Hidayah’s mother is the one standing, pouring the drinks. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.

Haji Yusoff’s grandchildren celebrating Hari Raya at Gedung Kuning in 1948. Hidayah’s mother is the one standing, pouring the drinks. Courtesy of Hidayah Amin.I recollect how neighbours from Kampong Glam would visit Gedung Kuning at Hari Raya. Once, a group of young men from Bussorah Street visited us. They were surprised to see me as I rarely hung outside the house. One teased me and said that if he knew Haji Jofrie had such a manis (sweet) granddaughter, he would have proposed to me! Such banter was a reflection of the good neighbourly spirit the people of Gedung Kuning had with the others.

Everyone would feast on the Hari Raya cookies and Nenek’s famous agar-agar kering (crystallised jelly), and help themselves to plates of the kepala meja – the main dish at the table – while quenching their thirst with Fraser & Neave orange crush. Warm smiles and laughter would break out amidst the lively conversations as one caught up with the happenings of another.

Children were the happiest during Hari Raya Puasa, especially those who had successfully completed a month of fasting. Proud parents would inform relatives of their feat, while the children beamed with pride at having accomplished one of the five pillars of Islam. I remember when I was spending Ramadan in Morocco, I met children dressed in their most lavish traditional clothes – the girls wore make-up and had their hair nicely coiffured – paraded around the village with drums beating to announce their accomplishment of one month of fasting.

But back in Gedung Kuning, children were celebrated in another way. True to the spirit of giving, Haji Yusoff would give five dollars (a big sum in those days) to each grandchild. In the 1930s, 10 cents could buy four sticks of satay from the satay man who carried his portable stove and cooked sur place. Wak Lah said that one cent could buy up to four different items of food, and that for two cents, he could have a cup of tea, pisang goreng (banana fritters) and a bowl of bubur kacang (green bean soup). Although five dollars could not buy that many things now, I agreed with Wak Lah when he said that it was not the duit raya (Hari Raya money) that mattered most, but the spirit of family togetherness experienced during Ramadan and Hari Raya. And how I missed that family togetherness when I was studying far away from home.

Gedung Kuning: Memories of a Malay Childhood is published by Singapore Heritage Society and Helang Books. The book retails for $24.90 (before GST) and is available at major bookshops. The book is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries. (Call nos.: RSING 305.8992805957 HID and SING 305.8992805957 HID)

Hidayah Amin is an award-winning author who has written several books and academic articles, and presented at international conferences. She has also produced more than 70 documentaries, audio resources and short films. Hidayah blogs at https://hida-amin.blogspot.sg/

Hidayah Amin is an award-winning author who has written several books and academic articles, and presented at international conferences. She has also produced more than 70 documentaries, audio resources and short films. Hidayah blogs at https://hida-amin.blogspot.sg/

NOTES

-

Gedung Kuning, along with the adjacent Istana Kampung Gelam in the Kampong Glam area, was restored and opened as the Malay Heritage Centre in 2004. The Istana, or Palace building, houses a a museum devoted to the history, heritage and culture of Malays in Singapore, while Gedung Kuning has been turned into a restaurant called Mamanda, which serves Malay cuisine. ↩