Land From Sand: Singapore’s Reclamation Story

Thanks to land reclamation, the tiny red dot has broadened its shores substantially. Lim Tin Seng discovers just how much Singapore has grown since colonial times.

Aerial photograph of ongoing reclamation work in Tuas. Photo by Richard W. J. Koh. All rights reserved, Koh, T. (2015). Over Singapore (pp. 108–109). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

Aerial photograph of ongoing reclamation work in Tuas. Photo by Richard W. J. Koh. All rights reserved, Koh, T. (2015). Over Singapore (pp. 108–109). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.Over the past two centuries, Singapore’s land area has expanded by a whopping 25 percent – from 58,150 to 71,910 hectares (or 578 to 719 sq km).1 This gradual increase in land surface is not because of tectonic movements or divine intervention, but rather the miracle of a man-made engineering feat known as land reclamation.

The quest for land is as old as time immemorial; one of the reasons nations go to war is to gain new territory to support a growing population. Land-scarce Singapore, however, has elected to create new land by reclaiming it from the rivers and the seas.

Boat Quay: The First Reclamation Project

Many people think of land reclamation in Singapore as a fairly recent phenomenon, but in actual fact the earliest reclamation project took place in colonial times. When Stamford Raffles landed at the mouth of the Singapore River in January 1819, the lay of the land was vastly different from what we see today. The river was flanked by mangrove swamps and mosquito-infested jungle, and what is now Telok Ayer Street and Beach Road were coastal areas that hugged the sea.

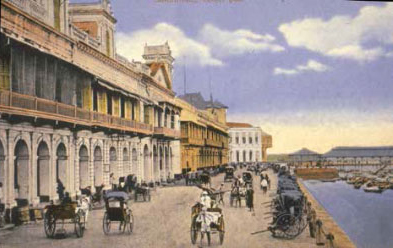

This lithograph (c. 1850) by Lieutenant Edwin Augustus Porcher from the British Royal Navy shows the view as seen from South Boat Quay, where Singapore’s first reclamation took place in 1822. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This lithograph (c. 1850) by Lieutenant Edwin Augustus Porcher from the British Royal Navy shows the view as seen from South Boat Quay, where Singapore’s first reclamation took place in 1822. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.It did not take long for the British to get down to business. Singapore was officially claimed by Raffles as a colony, and just four years later, the island witnessed the first of its many topographic transformations.

The first land reclamation project in Singapore took place in 1822 at the south bank of the Singapore River. Initially, Raffles had eyed the Esplanade-Rochor River beach front, north of Singapore River, as the commercial district. But as the area was unsuitable for shipping activities due to shallow waters and the surf, Raffles altered his town plan accordingly.2

As the south bank occupied a lowlying marsh that was prone to flooding, a hillock near where Battery Road is located today was levelled to provide earth to fill the wetlands. About 300 coolies were hired to carry out the work and an embankment was built along the river’s edge to prevent the water from overflowing into the land. The process took about four months and gave rise to a crescent-shaped area known today as Boat Quay. This, together with what was left of the hillock, became Commercial Square – and eventually, Raffles Place – the heart of the commercial district as mapped out in Raffles’ 1822 town plan of Singapore.3

Collyer Quay: Creating the Waterfront

Boat Quay and Commercial Square grew rapidly. By the late 1860s, the mercantile community had outgrown the site, spilling over to another reclaimed strip of land to the south. Known as Collyer Quay, this stretch – from Johnston’s Pier to the old Telok Ayer Market – was reclaimed between 1859 and 1864.4 This was part of a scheme conceived by the Municipal Engineer, George Chancellor Collyer.

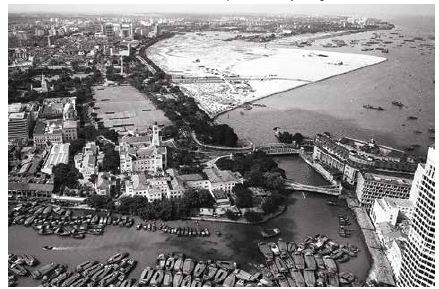

Named after George Chancellor Collyer, then Chief Engineer of the Straits Settlements, Collyer Quay was built on reclaimed land by convict labour and completed in 1864. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Named after George Chancellor Collyer, then Chief Engineer of the Straits Settlements, Collyer Quay was built on reclaimed land by convict labour and completed in 1864. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Collyer wanted to build a seawall to serve as a landing site and a road behind it so that merchants could have their establishments facing the waterfront. This would not only improve the “aspect of Singapore’s waterfront”, but also allow the merchants to keep an eye on the movement of ships carrying their goods. Indeed, some of the first buildings constructed along Collyer Quay were linked at the second storey by a verandah that faced the sea. Peons armed with telescopes would be stationed along the verandah to announce the arrival of their company ships.5

As work on the foundation of the seawall could be carried out only when the tide was at its lowest ebb, an occurrence that took place once every fortnight, the reclamation proceeded at a glacial pace. It took three years for the seawall to be completed and another year to lay the road behind it.6

First Reclamation at Telok Ayer: Redrawing the Coastline

In the late 1800s, Collyer Quay was further expanded when the Telok Ayer Reclamation Scheme was commissioned. Carried out between 1879 and 1897, it altered the shoreline of Telok Ayer by extending it seaward with a 42-acre tract.7 The aim was to create new land so that thoroughfares, including Cecil Street, Robinson Road and Raffles Quay, could be built to link the commercial district and the new port at Tanjong Pagar via Telok Ayer.8 Previously, these two areas were cut off by the hills of Mount Wallich, Mount Palmer and Mount Erskine, making the movement of goods between the port and town cumbersome.9

This reclamation project was a complex one as the Public Works Department (PWD) had to blast out parts of Mount Wallich and Mount Palmer in order to create an opening into Tanjong Pagar. The earth from the excavations was then used as landfill to create Telok Ayer Bay. The work was tedious as the hills were rocky and the sides had to be cut and graded. In addition, the shoreline had to be drained while keeping a section of it accessible so that fishermen could continue their trade. By 1886, the stretch extending into Cecil Street was completed, allowing the colonial government to start leasing the reclaimed land to merchants.10

Second Reclamation at Telok Ayer: An Unexpected Tidal Basin

As merchants moved into the reclaimed lands of Telok Ayer, commercial activities began to expand westward. This led to the development of Tanjong Pagar and the growing importance of New Harbour (renamed Keppel Harbour in 1900) as the main port-of-call in Singapore.11 However, many traders, especially those using smaller vessels such as prows and junks, still preferred to anchor near the Singapore River as it was closer to Commercial Square.

Between 1893 and 1903, the arrival of such vessels mushroomed from 7,062 to 10,974, causing the Singapore River to become congested and polluted. In October 1898, a Commission was appointed to address this problem. The report, issued in June 1899, recommended that a new harbour be built along Raffles Quay, precipitating the second reclamation project at Telok Ayer.12

The plan for the new harbour, unveiled in 1902 and revised in 1904, was drafted by the engineering firm Coode, Son & Matthews, and entailed reclaiming an 88-acre tract with a 5,000-ft long seawall that stretched from Johnston’s Pier to Tanjong Malang where Palmer Road stands today. The initial plans were more ambitious but, in the end, the authorities decided to scale back their plans due to budgetary constraints.13

Work began smoothly at first but in 1910, problems began to surface when dredging operations commenced. When engineers discovered that the seawall was sinking, work was suspended. At the time, 65 out of the 88 acres of land had been reclaimed and 4,120 feet of the seawall erected. However, as the construction of the seawall had been carried out simultaneously on both ends, the engineers were left with an incomplete seawall and a gaping 880-ft space in between.14

To salvage the project, engineers reinforced the foundations of the seawall and allowed it to settle for the next 10 years. Thereafter, the unclaimed area would be converted into a tidal basin for anchoring small vessels with the gap in the seawall serving as an entrance.15 Construction resumed in 1930 and was completed in 1932.16 By then, the cost of the project had ballooned from 2.5 to 15 million Straits dollars.17

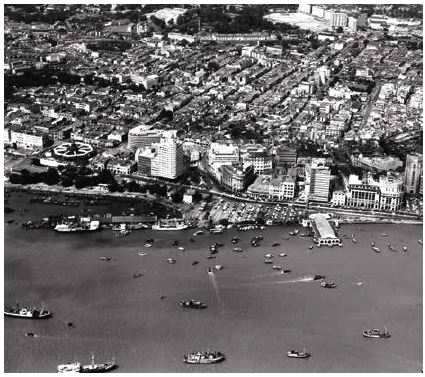

An aerial view of the Central Business District in the 1950s with the octagonal-shaped Telok Ayer Market (Lau Pa Sat) on the left and Clifford Pier jutting out into the sea on the right. In the foreground is Telok Ayer Basin where small vessels once anchored. The tidal basin was eventually reclaimed in the 1970s. © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

An aerial view of the Central Business District in the 1950s with the octagonal-shaped Telok Ayer Market (Lau Pa Sat) on the left and Clifford Pier jutting out into the sea on the right. In the foreground is Telok Ayer Basin where small vessels once anchored. The tidal basin was eventually reclaimed in the 1970s. © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.Kallang Basin and Beach Road

The hefty cost of the Telok Ayer Tidal Basin project did not stop the colonial government from commissioning more reclamations. In August 1931, it unveiled a massive reclamation project at Kallang Basin for the construction of Kallang Airport. Costing 9 million Straits dollars, it involved the reclamation of 339 acres of mangrove swamp dubbed “the worst mosquito-infested land on the island”. Due to the complexity and cost, the PWD was asked to lead the project. And perhaps to prevent the repetition of the Telok Ayer Basin fiasco, the PWD first carried out extensive soil surveys. It also allowed large areas of the basin to dry out completely first before filling it.18

The filling operation started in May 1932 using a workforce of over 400 coolies. When completed in October 1936, the construction of the airport had already started.19 Comprising a terminal building, two hangars, a circular landing field and a slipway for seaplanes, it occupied almost three quarters of the 339 acres of reclaimed land. The remaining land was set aside for the airport’s future expansion. Kallang Airport was declared opened in June 1937 by Governor Shenton Thomas, who declared it the “finest airport in the world”. PWD Director Major R. L. Nunn said that it was an “audacious engineering achievement”.20

Even as Kallang Basin was being reclaimed, the authorities had embarked on another project in June 1932. This would add 47 acres to the Beach Road Reclamation site to create a foreshore that would stretch from Stamford Road to Rochor River. The site, also known as Raffles Reclamation Ground, was created by two earlier reclamations that took place in the 1840s and 1890s. The reclaimed land was used to build Alhambra and Marlborough cinemas, Beach Road police station, and the Singapore Volunteer Corps Headquarters and Drill Hall (the former Beach Road Camp). The open land also regularly hosted football matches and circus shows.21

This latest reclamation plan would turn the Beach Road shoreline into a “new waterfront”, with a bridge built over Stamford Canal to provide a “waterfront drive” from Anderson Bridge to Kallang. To complement this vision, a 6-acre reclamation project was commissioned in 1939 to enlarge the Esplanade along Connaught Drive to create a 600-yard tract linking Anderson Bridge to Stamford Canal.

The Beach Road and Esplanade reclamations were completed at a cost of about 1.2 million Straits dollars. However, the waterfront vision did not materialise until after World War II when Merdeka Bridge (now Nicoll Highway) was built and the Esplanade reclamation site was turned into a park known as Queen Elizabeth Walk (now Esplanade Park).22

The Kallang Basin and Beach Road reclamations would be the last major land reclamation projects in colonial Singapore. It would take another 30 years before any more new land would be reclaimed from the sea. In total, about 300 hectares (3 sq km) were added during the colonial period. While this is not a figure to be sniffed at given the technology available at the time, it would be dwarfed by the island’s post-Independence reclamation activities. Between 1965 and 2015, Singapore would reclaim an astounding 13,800 hectares (138 sq km) of land.23

East Coast: The Great Reclamation

The first major post-Independence reclamation project was the East Coast Reclamation. Dubbed the “Great Reclamation”, it added a 1,525-hectare tract along the southeastern coast of the island.24 The project was undertaken by the Housing and Development Board (HDB), one of three government agencies appointed to carry out land reclamation in Singapore. But first, before any work began, a pilot project was carried out by the HDB in 1963 to reclaim 48 acres in the Bedok area.

Work on the East Coast Reclamation site began officially in 1966 and would continue for a remarkable 30 years over seven phases.25 Phases I and II from Bedok to the tip of Tanjong Rhu took place between 1966 and 1971, resulting in 458 hectares of land as well as a 9-km stretch of sandy beach. Phases III and IV began simultaneously in 1971 at both ends of the newly reclaimed East Coast strip. When work was completed in 1975, Phase III had added 67 hectares of land to the foreshore fronting Tanjong Rhu and Queen Elizabeth Walk, while Phase IV added 486 hectares from Bedok to Tanah Merah Besar.

Phase V involved the reclamation of Telok Ayer Basin. Starting in 1974, it extended the already reclaimed foreshore by 34 hectares and expanded the basin.

On completion of this phase in 1977, the reclamation formed a new site known as Marina Centre and a massive lagoon. This was followed by another two phases in 1979 – Phases VI and VII – which extended the newly reclaimed foreshores of Tanjong Rhu and Telok Ayer Basin to create Marina East and Marina South respectively. Together with Marina Centre, these plots formed a 660-hectare reclaimed site called Marina City and later Marina Bay.26

The total cost of the East Coast project was $613 million. Fill materials were obtained from multiple sources, including Siglap Plain and the hills in Bedok and Tampines,27 where the earth was cut by bucket wheel excavators before being transported by a conveyor belt to a jetty off Bedok. There, the earth was loaded onto barges and transported to fill the area to be reclaimed. The entire operation was carried out around the clock, with headlands constructed at regular intervals off the reclaimed coast to protect the newly formed shoreline.28

The reclaimed lands were used largely for commercial and residential purposes. In the east coast, housing estates such as Marine Parade and Katong sprang up, providing accommodation for an estimated 100,000 residents.29 To link the housing estates as well as the commercial centres in Siglap, Joo Chiat and Bedok to the city, a major arterial road, the East Coast Parkway, was constructed along the newly reclaimed coast. Parallel to the expressway, a linear park was built to provide recreational space for residents. Today, East Coast Park comprises 185 hectares of parkland and a scenic 15-km beach.30

The East Coast district of Singapore with Katong in the foreground. Marine Parade stretches from the flyover to the lagoon near Bedok Jetty. The strip parallel to Marine Parade Road with the highrises is land that has been reclaimed from the sea. Photo by Richard W. J. Koh. All rights reserved, Koh, T. (2015). Over Singapore (pp. 140–141). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

The East Coast district of Singapore with Katong in the foreground. Marine Parade stretches from the flyover to the lagoon near Bedok Jetty. The strip parallel to Marine Parade Road with the highrises is land that has been reclaimed from the sea. Photo by Richard W. J. Koh. All rights reserved, Koh, T. (2015). Over Singapore (pp. 140–141). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.The other end of the reclaimed land around Marina Bay was to provide space in time to come for the expansion of the city centre. Amazingly, the idea of this new downtown core was conceived several decades before the first soaring skyscrapers arose here in the 21st century. Today, the Marina Bay area has become the new downtown with a stunning waterfront setting and a mix of office and commercial developments, a mega hotel and casino resort, high-rise luxury apartments, and gardens and parkland.31

The East Coast Reclamation, which began in 1966, was carried out over seven phases spanning some 30 years. The project culminated in the creation of Marina Bay in the mid-2000s. In the background of this photograph taken in 1976 are the beginnings of the Marina Bay reclamation site taking shape, with the east coast in the far distance. © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

The East Coast Reclamation, which began in 1966, was carried out over seven phases spanning some 30 years. The project culminated in the creation of Marina Bay in the mid-2000s. In the background of this photograph taken in 1976 are the beginnings of the Marina Bay reclamation site taking shape, with the east coast in the far distance. © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.To make this a reality, further reclamation was carried out around the bay between 1990 and 1992 to create an urban waterfront promenade. This 38-hectare project involved filling up Telok Ayer Basin as well as extending Collyer Quay and the shoreline of Marina South facing Marina Bay.32

Other Reclamation Projects by HDB

While the east coast was being reclaimed, the HDB simultaneously carried out reclamation projects elsewhere on the island. In 1963, the reclamation of Kallang Basin began, with some 400 hectares of its swampland filled using earth taken from Toa Payoh. Completed in 1971, the site was used for public housing and industrial development.33

Next, the HDB reclaimed a stretch along Singapore’s west coast between 1976 and 1978 to create 89 hectares of land for the development of Clementi New Town. Along with it, the West Coast Highway was constructed to link Jurong with the eastern part of the island. The fill materials for this project were excavated from Clementi.34

This was followed by several other reclamation projects: the addition of 44 hectares of land along the coast of Pasir Ris between 1979 and 1980, 277 hectares of swampland off Punggol between 1983 and 1986 as well as the reclamation of 685 hectares of foreshore and swampland along the northeast coast from Pasir Ris to Seletar between 1985 and 2001.35

The latter included the reclamation of 155 hectares from the foreshore of Coney Island and Punggol. Fill materials for these projects were either imported or obtained from sites in Woodlands, Tampines, Pasir Ris, Yishun, Seletar and Zhenghua.36 Much of the new land was reserved for public housing and recreational purposes.

Additionally, the HDB embarked on reclamation projects for other government agencies. For instance, between 1990 and 1995, it reclaimed about 30 hectares of land in the north and northwest for the Ministry of Home Affairs to expand the Woodlands Checkpoint and construct the new Tuas Checkpoint respectively. The HDB also carried out reclamation works for the Singapore Tourism Board and Ministry of National Development on Pulau Ubin and the Southern Islands.37

Between 1965 and 2015, the HDB reclaimed 3,869 hectares of land – roughly one third of the total reclaimed land on the island. The rest were overseen by two other government agencies, the Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) and the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore.38

New Lands for Industries: JTC

The reclamation projects undertaken by JTC in the west of the island were mainly for industries. The earliest project took place in 1963 to reclaim 46 hectares of land for the Jurong Industrial Site. This was followed by a string of reclamations in the 1970s that added over 2,000 hectares in Jurong and Tuas. These lands were used for the expansion of the industrial estate as well as for the construction of shipyards to support the marine sector. In the late 80s, the Tuas site was further extended by 650 hectares, and a golf course and a park subsequently added to inject some greenery to an otherwise industrial area.39

JTC’s reclamation works also extended to the islands off the southwestern coast. From the late 1980s, Pulau Bukom and Pulau Busing were enlarged, while Pulau Ayer Merbau, Pulau Seraya and Pulau Sakra were merged with the surrounding islets to provide new land. Most of these reclaimed islands were used for the petrochemical industry.40

As the industry grew, JTC embarked on a reclamation scheme of mega proportions in 1993, merging seven southwestern islands – Pulau Merlimau, Pulau Ayer Chawan, Pulau Ayer Merbau, Pulau Seraya, Pulau Sakra, Pulau Pesek and Pulau Pesek Kecil – into a single entity called Jurong Island. The massive project was carried out in four stages at a cost of $6 billion. When completed in 2003, Jurong Island gave Singapore a substantial 3,000 hectares of new industrial space. Today, Jurong Island is home to more than 100 petroleum, petrochemical and speciality chemical companies.41

New Lands for Infrastructure and Recreation: MPA

The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) – formerly Port of Singapore Authority or PSA – reclaimed land primarily to develop the Port of Singapore and Changi Airport. Its earliest project took place in 1967 when 23 hectares of land were reclaimed to build Singapore’s first container terminal at Keppel Harbour. The Tanjong Pagar Container Terminal opened in 1971 with three container berths.42

Between 1972 and 1979, some 61 acres of foreshore along Pasir Panjang were reclaimed by the PSA. This was part of a larger effort to move lighter cargo operations from Telok Ayer Basin, Rochor River and Kallang River to a new wharf with warehousing and berthing facilities for lighters and coastal vessels.43 A decade later, PSA announced additional reclamation works at Pasir Panjang to construct a new container terminal. The first two phases were carried out from 1993 to 1999.44 In June 2015, reclamation works under the final two phases were launched and are slated for completion by the end of 2017.45

PSA’s reclamation works for Changi Airport began in 1975 when it supervised the reclamation of 745 hectares of land along Changi coast for the construction of the airport.46 The adjoining seabed provided the fill material. In 1990, another massive reclamation was carried out for the expansion of Changi Airport as well as for mixed-use developments in the area.

Since the first reclamation works began in 1822, Singapore’s land area has expanded by almost 25 percent from 58,150 to 71,910 hectares. The areas shaded in pink indicate how much has been reclaimed thus far. The areas in red show possible plans for future reclamation and indicate how much of the island’s original coastline may change by 2030 if these plans come to fruition. Map source: https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/hp331-2014-10/?page_id=7

Since the first reclamation works began in 1822, Singapore’s land area has expanded by almost 25 percent from 58,150 to 71,910 hectares. The areas shaded in pink indicate how much has been reclaimed thus far. The areas in red show possible plans for future reclamation and indicate how much of the island’s original coastline may change by 2030 if these plans come to fruition. Map source: https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/hp331-2014-10/?page_id=7The plans were updated in 1998 – by which time PSA had been renamed MPA – to reclaim over 2,000 hectares of land at Changi East. About 820 hectares were allocated for the development of a fourth terminal and a third runway, while 125 hectares and 639 hectares were reserved for the Changi Naval Base and industries respectively.47 The reclamation was carried over five phases from 1992 to 2004.

Like HDB, the MPA has been helping other government agencies to reclaim islands around Singapore. Using dredged materials from ongoing reclamation projects, which would otherwise be dumped into the sea, public beaches and recreational waterfronts were created at the foreshore of the Southern Islands. On St John’s Island, Lazarus Island, Sisters’ Island and Kusu Island, facilities such as landing jetties, chalets, beach shelters and sanitary facilities were built on the reclaimed land.48 Over in Sentosa, reclaimed land has been used to build hotels and a golf course, and to create new beaches.

MPA also undertook the first reclamation of Pulau Tekong (formerly known as Pulau Tekong Besar). Carried out between 1981 and 1985, it reclaimed 540 hectares of foreshore using fill materials from Changi and imported from neighbouring countries.49 The enlarged island was subsequently used by the Ministry of Defence as a training site for the military.50 In 2000, another reclamation effort to enlarge Pulau Tekong by a further 3,310 hectares was approved. Overseen by the HDB, it involved merging the smaller Pulau Tekong Kechil island with Pulau Tekong.51

The Future

It is certain that land-scarce Singapore will press ahead with reclamation to meet the demands of its growing population in the foreseeable future. In the 2013 Land Use Plan, the Ministry of National Development has noted that there is a need to provide an additional 5,600 hectares of land by 2030. This is to accommodate the expected increase in population, rising from the present 5.7 million to between 6.5 and 6.9 million.

But there are limits to land reclamation – the rising cost of imported sand, the deleterious impact on the ecosystem and the encroachment of shipping lanes and territorial limits, among others. As an aggressive land reclamation programme is not tenable in the long term, Singapore is looking at other ways of maximising its land space; this includes the development of reserve land, intensifying land usage in new developments, and reusing and rezoning old industrial areas and golf courses for more productive purposes.52

LAND RECLAMATION: HOW DOES IT WORK?

The proposed site for reclamation is first investigated to determine seabed conditions, availability of fill materials as well as the shape and alignment of the reclaimed area. Environmental studies are then carried out to assess the impact on water quality, water level, tidal flow, sedimentation and marine life.

Work proper begins with the erection of containment dykes made of sand and rock around the perimeter of the area to be reclaimed. Materials such as cut-hill soil, sand and clay are then transported from other sites to fill the enclosed area. The newly reclaimed land must be allowed to settle naturally over time before any structures can be built. In most cases, however, the process is speeded up with soil improvement methods.53

Reclamation work taking place at Pasir Panjang. With rising costs and restrictions on sand exports placed by neighbouring countries, Singapore has turned to technology to try reduce the amount of sand needed for reclamation work. Photo by Ria Tan. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

Reclamation work taking place at Pasir Panjang. With rising costs and restrictions on sand exports placed by neighbouring countries, Singapore has turned to technology to try reduce the amount of sand needed for reclamation work. Photo by Ria Tan. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

Since the first reclamation project carried out in 1822, fill materials have traditionally comprised soil excavated from inland hills and sand dredged from surrounding seabeds. By the mid-1980s, however, these resources began to run out and Singapore had to import sand from neighbouring countries. This soon became a problem when the cost of foreign sand skyrocketed from less than $20 per sq m in the 1970s to $200 per sq m in the 90s. The situation hit crisis levels when Malaysia and Indonesia banned the export of sand to Singapore in 1997 and 2007 respectively.

Although Singapore had to turn to other countries for sand, it recently developed a more sustainable method that has reduced the amount of sand needed for reclamation works. Called empoldering, it has since been successfully deployed by the HDB for the on-going reclamation of Pulau Tekong.54

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Singapore Land Authority. (2016, May 19). Total land area of Singapore. Retrieved from Data.gov.sg website; Tan, H.T.W., et al. (2010).The natural heritage of Singapore (p. 78). Singapore: Prentice Hall. (Call no.: RSING 508.5957 NAT) ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (pp. 68, 75). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC ↩

-

Buckley, 1984, pp. 75, 82–83, 88–89; Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2016, July 28). Boat Quay. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Collyer of Quay fame. (1933, June 29). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 88. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Buckley, 1984, p. 689. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 29 Jun 1933, p. 88; Buckley, 1984, p. 689; Tyers, R.K. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then and now (pp. 103, 114–115). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TYE) ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 29 Jun 1933, p. 88; Buckley, p. 689. ↩

-

Summary of the week. (1879, August 5). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 1; Teluk Ayer reclamation. (1896, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 2; Teluk Ayer. (1897, June 28). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dale, O.J. (1999). Urban planning in Singapore: Transformation of a city (p. 18). Shah Alam, Malaysia: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216 DAL); Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore River: A social history 1819–2002 (pp. 11–12). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOB) ↩

-

Picturesque and busy Singapore. (1887, February 7). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 7; Harbour and town improvement. (1902, January 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 4 advertisements column 5. (1886, March 5). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Westward ho!. (1891, September 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3; Harbour improvement scheme. (1904, October 22). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Dale, 1999, pp. 18–19 ↩

-

Dobbs, 2003, pp. 10–11; Legislative Council. (1898, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 3; The Singapore River. (1899, June 14). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Harbour. (1902, January 23). The Straits Times, p. 3; The harbour scheme. (1904, June 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 3; Singapore River improvements. (1906, December 13). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Important Singapore port improvement. (1932, September 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 4; Untitled. (1910, August 17). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 6; Telok Ayer scheme. (1921, March 23).* The Straits Times*, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore harbour: Return to an old idea. (1911, December 15). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 23 Mar 1921, p. 11; The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 27 Sep 1932, p. 4. ↩

-

Telok Ayer Basin. (1932, September 24). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 27 Sep 1932, p. 4. ↩

-

Singapore Harbour works. (1919, September 3). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nine million dollar airport opens. (1937, June 13). Sunday Tribune (Singapore), p. 1; New airport is on former swamp site. (1937, June 12). The Straits Times, p. 10; Key position in sea and air communications. (1937, June 14). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore’s civil aerodrome. (1932, June 14). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884– 1942), p. 8; Design and construction of Singapore’s new civil Aerodrome. (1934, November 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 4; The colonial secretary’s review of the year improving soil on estates. (1936, October 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 1 Nov 1934, p. 4; The Straits Times, 12 Jun 1937, p. 10. The Straits Times, 14 Jun 1937, p. 18; Governor opens airport. (1937, June 13). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New waterfront scheme may be postponed. (1940, July 22). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Dorai, F. (2016). South Beach: From sea to sky: The evolution of Beach Road (p. 26). Singapore: South Beach. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOR); Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (p. 32). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV) ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 22 Jul 1940, p. 5; Mrs McNeice opens Queen Elizabeth Walk & Gardens. (1953, May 31). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pui, S.K. (1986). 100 years of foreshore reclamation in Singapore. 20th International Conference on Coastal Engineering, ASCE, Taipei, Republic of China (p. 2631). Retrieved from ACSE Library website; Singapore Land Authority. (2016, May 19). Total land area of Singapore. Retrieved from Data.gov.sg website. ↩

-

The great land reclamation at East Coast. (1983, November 21). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board. (1963–). Annual report 1966 (pp. 10–11). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1972, p. 45; Housing and Development Board, 1977/78, p. 38; Housing and Development Board, 1980/81, p. 41; Goh, H.C., & Heng, C.K. (2016). Shaping Singapore’s cityscape through urban design. In Heng, C.K. (Ed.), 50 years of urban planning in Singapore (p. 228). Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 FIF); Loo, D. (2005, July 22). Marina Bay the new brand name. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1980/81, p. 41; Campbell, W. (1970, June 30). On the waterfront things are moving. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1966, pp. 10–11; Housing and Development Board, 1967, p. 48; Housing and Development Board, 1972, p. 45; Housing and Development Board, 1977/78, p. 38. ↩

-

Campbell, W. (1971, August 8). Where 100,000 will live and play on reclaimed East Coast. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 Nov 1983, p. 7; National Parks Board. (2016, June 28). East Coast Park. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Auger, T. (2015). A river transformed: Singapore River and Marina Bay (pp. 90–91). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 711.4095957 AUG); Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2015). The Marina Bay story. Retrieved from Marina Bay website. ↩

-

Lee, H.S. (1989, October 3). URA to start selling Marina South sites in 1992/1993. The Business Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1963, p. 43; Housing and Development Board, 1966, p. 46; Housing and Development Board, 1966, p. 45. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1977/78, p. 38. ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1979/80, p. 34; Land reclamation off Punggol. (1983, March 5). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1984, October 19). Reclamation at Punggol (Vol. 44, col. 2095). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN); Reclamation project approved. (1984, October 20). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Chia, L.S., et. al. (1988). The Coastal environmental profile of Singapore (p. 43). Manila: International Centre for Living Aquatic Resources. (Call no.: RSING 333.917095957 CHI) ↩

-

Tan, Y.H. (2009, December 20). Punggol renewal. The Straits Times, p. 51. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1997, July 28). Estimates of expenditure for the financial year 1st April, 1997 to 31st March, 1998 (Vol. 67, col 1123). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Housing and Development Board, 1990/91, p. 48; Housing and Development Board, 1994/95, p. 53; Housing and Development Board, 1999/2000, p. 59. ↩

-

Government of Singapore. (2017, February 4). Cumulative area reclaimed for engineering projects. Retrieved from Data.gov.sg; Chia,1988, p. 41. ↩

-

Singapore. Legislative Assembly. Debates: Official report. (1963, June 15). Tan Kia Gan, Minister for National Development (Vol 20, cols 1332–1333). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN); Chia, 1988, p. 43. ↩

-

Jurong Town Corporation. (2002). The making of Jurong Island: The right chemistry (pp. 19, 24, 41, 46, 47). Singapore: Jurong Town Corporation. (Call no.: RSING 711.5524095957 MAK); Jurong Town Corporation. (2003). Happy birthday: Commemorating 35 years of JTC Corporation, 1968–2003 (pp. 19–22). Singapore: Jurong Town Corporation. (Call no.: RSING 338.095957 HAP); Jurong Town Corporation. (2017, January 16). Jurong Island. Retrieved from Jurong Town orporation website. ↩

-

55 acres of land from sea by year’s end. (1967, August 8). The Straits Times, p. 22; Reclamation of East Lagoon Now Completed. (1968, September 6). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Port of Singapore Authority. (2017). Our business: terminals. Retrieved from PSA Singapore website. ↩

-

Land to be reclaimed for warehouses. (1971, July 31). The Straits Times, p. 4; $75m. warehouse project completed. (1972, May 2). New Nation, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tender for Pasir Panjang terminal. (1992, October 30). The Business Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1992, May 29). Reclamation Pasir Panjang) (Vol. 60, col. 36). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Lim, A. (2015, June 24). Pasir Panjang Terminal’s $3.5b expansion kicks off. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Biggest land reclamation contract in S-E Asia. (1976, March 4). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘Yes’ to reclamation at Sentosa and Changi East. (1990, November 10). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

St. John’s Island to become holiday resort. (1976, January 23). The Straits Times, p. 13; Ho, R. (1977, April 27). ‘New’ island for Raffles Lighthouse. New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chia, 1988, p. 44; Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1981, February 20). Pulau Tekong Besar (reclamation) (Vol. 40, cols. 289–290). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (1988, March 28). Reclaimed land at Pulau Tekong Besar (development plans) (Vol. 50, col. 1495). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Parliamentary debates: Official report. (2000, February 22). Reclamation at Pulau Ubin and Pulau Tekong (Vol. 71, col. 1049). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

Ministry of National Development. (2013, January). A high quality living environment for all Singaporeans: Land use plan to support Singapore’s future population, pp. 12–14. Retrieved from Ministry of Development website. ↩

-

Yang, L. (2003). Mechanics of the consolidation of a lumpy soft clay fill (p. 2). [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Retrieved from National University of Singapore website. ↩

-

Yang, 2003, p. 3; Chia, A. (2016, November 16). New reclamation method aims to reduce Singapore’s reliance on sand. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩