East of Suez: The Mystique of Travel

Rudyard Kipling coined the phrase “East of Suez” to describe the exotic lands east of the Suez Canal. Kennie Ting goes back to a time when people were travellers, not tourists.

Steamers passing through the Suez Canal. The 164-km long and 54-metre-wide canal – which opened on 17 November 1869 – linking the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea changed the course of maritime history forever as it paved the way for the advent of long distance leisure travel. Ships heading East from Europe no longer had to traverse the Cape of Good Hope and the western coast of the African continent to get to Arabia. Kennie Ting Collection.

Steamers passing through the Suez Canal. The 164-km long and 54-metre-wide canal – which opened on 17 November 1869 – linking the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea changed the course of maritime history forever as it paved the way for the advent of long distance leisure travel. Ships heading East from Europe no longer had to traverse the Cape of Good Hope and the western coast of the African continent to get to Arabia. Kennie Ting Collection.“Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there aren’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst;

For the temple-bells are callin’, an’ it’s there that I would be —

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking lazy at the sea…”1

– Rudyard Kipling, “Mandalay”

Imagine, if you can, standing at the edge of the passenger platform, on the banks of the Suez Canal. It’s been two weeks since you arrived in Egypt, one month since leaving Southampton. And now here you are in Port Said, waiting to board your next ship for the onward journey to British India, and beyond that, the Far East.

Your bags are packed. They sit innocuously at the rear. Your manservant is counting the pieces, to make sure everything arrived safe and sound from the Hotel de l’Europe in Port Said. He has been at your side for the entire journey, making sure you feel at home away from home, everywhere you go. You glance to your right, at the well-dressed lady who is similarly waiting to board the ship. She appears to be travelling alone too, and her maidservant stands by her, sheltering her from the heat of the tropical sun with a sturdy parasol. Your eyes meet. You lift your hat slightly and nod. She acknowledges it with a slightly hesitant smile. Will you see her again on board the ship, you wonder…

A painting by the French shipping company, Compagnie des Méssageries Maritimes, depicting life on board one of its cruise liners. If one travelled first class, travel by ship was as opulent and luxurious as any hotel establishment could offer. Kennie Ting Collection.

A painting by the French shipping company, Compagnie des Méssageries Maritimes, depicting life on board one of its cruise liners. If one travelled first class, travel by ship was as opulent and luxurious as any hotel establishment could offer. Kennie Ting Collection.The year is 1928. Our gentleman tourist has just embarked on his cruise to the Far East and is at present about to head “East of Suez” – what the European powers called their colonial dominions lying to the east of the Suez Canal. The phrase itself had been made popular by the poem Mandalay, published in 1890 by Rudyard Kipling, the celebrated chronicler of the British Empire and doyen of all things Far Eastern.

Suez Canal and its Impact on Travel

The Suez Canal took nearly 15 years to build, from the time it was envisioned in 1854 by a Franco-Egyptian consortium to its actual completion in 1869, as the project was beset by political and financial disputes, engineering issues and chronic labour shortages. On 17 November 1869, in a lavish ceremony held at Port Said in Egypt, the 164-km-long and 54-metre-wide canal linking the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez was declared open, changing the course of maritime history forever.

For the first time, ships heading East from Europe no longer had to traverse the Cape of Good Hope and the western coast of the African continent just to get to Arabia, less than 2,000 miles south of Greece. Months were shaved off the journey, and this proved pivotal to long distance maritime trade and paved the way for the advent of leisure travel to faraway lands.

Prior to the opening of the Suez Canal, only colonial civil servants or merchants with interest in far-flung foreign dominions would elect to travel to the East. By and large, the leisure traveller was a rare sight: one had to be fairly intrepid – or foolhardy – to take such a long and arduous journey. However, by the 1880s, a small number of leisure travellers, taking advantage of the shortened journey via the Suez, would venture forth where no other in their time had been before – and return to recount their tales.

The first of these adventurous travellers were accommodated as passengers on board mail or cargo steamers, putting up with basic facilities that were meant for much hardier members of the crew. By the turn of the 19th century, however, “pleasure cruises” had become a viable industry. The Great War (1914–18) – later known as World War I – did little to quell demand and, by the early 1920s, the cruise liner industry was at its peak.

For Europeans and Americans in the 1920s, newly affluent and with an insatiable curiosity for seeing a world they had hitherto read about in journals and heard about in news broadcasts, the East presented a thrilling, albeit somewhat fantastical counterpoint to the West, with its social niceties, its modern conveniences and its increasingly hectic pace of life.

Brochures from the major shipping lines of the era, as well as independent tour agencies such as Thomas Cook & Son, Raymond & Whitcomb Company and American Express’ Travel Department, reinforced this impression of the East as an exotic and idyllic haven, often describing the passage East with words and phrases that invoked a return to innocence, or at least to a simpler and more spiritual existence.

Mind-boggling distances and unfamiliar cultures were rendered far more manageable and immediate through detailed descriptions and evocative photographs that brought the locale to life on paper to the would-be traveller. The journey itself was promoted as one of discovery, both of uncharted territory and of the self. By undertaking these passages East, the average upper middle-class European or American could fancy him or herself as following in the illustrious footsteps of great explorers, adventurers and travel writers before them. To aspire was to explore.

When Travel was Leisure

In response to a heightened demand for travel, shipping lines and tour agencies began to offer round-the-world cruises as early as the 1910s. These were trips that circumnavigated the globe, stopping off briefly at a string of major cities. Catering to a select group of wealthy persons of leisure, or famous celebrities and writers, these round-the-world journeys by steamships could take up to a whole year or more, with travellers stopping over for months at a time at major ports, absorbing the sights and experiencing the local histories and cultures at their leisure. Holidays in the pre-jet era, for those who could afford them, were extended, indulgent breaks for rest, recreation and on occasion, recuperation.

Of course, passengers on services out East did not just include vacationers. The bulk of these passengers continued to be businessmen and colonial officials; and significantly after World War I, new immigrants, seeking out a fresh start in the far-flung colonies of the home countries. They, too, would have been attracted to an image of the East as a land of opportunity, where fortunes could be made.

Unlike the historic Grand Tours of continental Europe, which began in the late 1700s and remained a popular rite of passage for wealthy elites in Britain and America well into the 1900s, the intent of undertaking a round-the-world Grand Tour that took one to the East wasn’t so much to better or educate one’s self, but to experience something new and exotic – leisure, rather than self-advancement. There was also an undeniable degree of colonial superiority involved in the Grand Tourists’ gaze, which tended to objectify unfamiliar Eastern cultures and judge them as inferior to the West, rather than attempt to understand them on an equal footing.

Go East, Young Man

The customary stops on Grand Tours of the East depended in large part on the Colonial Empire from which the traveller hailed. Generally, the tour took in a handful of major port cities – Bombay, Colombo, Calcutta, Rangoon, Singapore, Batavia, Saigon, Hanoi, Manila, Hong Kong, Macao, Tientsin, Shanghai and others, before terminating in the treaty port cities of Kobe or Yokohama in Japan. Those with time and money to spare would use these port cities as a base, from which to take excursions to major historic sites and centres of culture – the palaces of Rajasthan, the ruins of Bagan, Angkor, Borobudur and Ayutthaya, and the imperial cities of Peking and Tokyo.

Batavia and Shanghai were popular ports of call for tourists on the Grand Tour of the East. (Left) The Amsterdam Gate in Batavia, which existed from 1744 to the 1950s, formed the entrance to the Castle Square south of Batavia Castle. (Right) This is a view of the historic Bund, the waterfront area in Shanghai that runs alongside the Huangpu River. Both photos are from the Kennie Ting Collection.

Batavia and Shanghai were popular ports of call for tourists on the Grand Tour of the East. (Left) The Amsterdam Gate in Batavia, which existed from 1744 to the 1950s, formed the entrance to the Castle Square south of Batavia Castle. (Right) This is a view of the historic Bund, the waterfront area in Shanghai that runs alongside the Huangpu River. Both photos are from the Kennie Ting Collection.Southeast Asia – or the East Indies, as this part of the world was known then – was an important stopover between India and the Far East, not least because of its geographical location between the two areas. Rather, the East Indies was important because it was here, in this far-flung landscape of peninsulas and archipelagos, that major colonial European powers had carved out significant territories to leave their imprint. Southeast Asia, in other words, was an extension of Europe (and America) itself, and its cities familiar re-creations of the imperial cities back home – London, Paris, Amsterdam – offering respite to the Grand Tourist in between the vast, alien expanses of India and China.

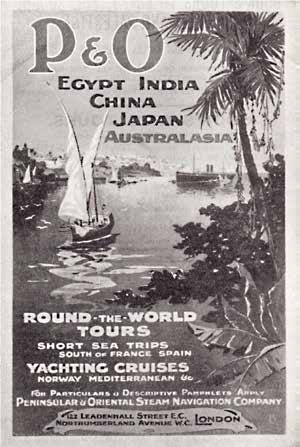

The cruise liner market was dominated by a few major shipping companies, most of which were considered “national” lines, much like the national airline carriers of today. The largest of these companies was the Peninsula & Oriental Steam Navigation Company, better known as P & O, established in 1837 in Southampton, England, to deliver mail on behalf of the British Empire to the Iberian Peninsula, and subsequently to the city of Alexandria. From Egypt, the company expanded its operations out East as far as China and Japan, acquiring and merging with other steamship companies to secure its position as the foremost shipping line in the world by the early 1900s.

In response to an increased demand for travel, shipping lines and tour agencies began to offer round-the- world cruises as early as the 1910s. This is an advertisement from the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company promoting its round-the-world tours and cruises to the exotic Far East. Kennie Ting Collection.

In response to an increased demand for travel, shipping lines and tour agencies began to offer round-the- world cruises as early as the 1910s. This is an advertisement from the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company promoting its round-the-world tours and cruises to the exotic Far East. Kennie Ting Collection.The other colonial powers had P & O equivalents: the French Compagnie des Méssageries Maritimes (literally “maritime packet company”), more commonly known as Méssageries Maritimes, was established in 1851. Headquartered in the Mediterranean port city of Marseille in France, their “paquebots” (as the French called their steamships) were to be seen in all major port cities in the Middle East, and by the 1900s, with Saigon in Vietnam as its second headquarters, also in the Far East.

The Dutch established the Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij (Royal Packet Navigation Company), or KPM, in 1888, in its capital, Amsterdam. With Batavia in the Dutch East Indies as its Eastern headquarters, the KPM brought significant trade and passenger traffic to Java, cementing Batavia’s position as a global entrepôt and a formidable competitor to Singapore in the region.

Modes of transportation on round-the-world tours were not limited to maritime steamships. Tour agencies were committed to making the most of existing sea, river, land and, from the late 1920s onwards, fledgling air travel networks in the region to take the Grand Tourist where he or she wanted to go. But the steamship and cruise liner would remain the most evocative, romantic and visible symbol of long-distance luxury travel for much of the first half of the 20th century.

Life on the High Seas

Life on board the cruise liner, particularly, if one travelled first class, was as opulent and luxurious as any hotel establishment could offer, with shipping lines constantly competing with one another to put out the speediest, smoothest and most luxurious ships in the market. No cost and effort was spared in ensuring that the interiors of these ships afforded a sense of decadence and privilege. In fact, many of the dining halls, lounges and smoking rooms were often theatrical in outlook and design, reinforcing the impression that one was participating in a kind of sweeping epic drama on the high seas.

Everyday life on board the ship typically revolved around food and entertainment. The former was abundant – the gong would sound at appropriate intervals of the day for breakfast, lunch, tea, dinner and supper. Wine and beer would flow freely, and champagne would be popped for first-class passengers. Guests would be dressed to the nines outside of their private staterooms; particularly for dinner, where they would join other guests in the capacious dining rooms, to be treated to multi-course meals and regaled by resident musical ensembles.

In between meals, social activity centred on the common spaces: open-air promenade decks, the lounge halls and the smoking rooms, the latter restricted only to first-class male passengers, who would idle their time away on card games, drinks and conversation, all the while puffing away on a cigar or cigarette.

(Left) Passengers dressed in their best on a cruise liner belonging to the German-owned Norddeutscher Lloyd company in 1912. Cruising was very much a formal affair then, with male passengers dressed in suits, and ladies in neck-to-ankle blouse and skirt ensembles and extravagant large hats. John Koh Collection.

(Left) Passengers dressed in their best on a cruise liner belonging to the German-owned Norddeutscher Lloyd company in 1912. Cruising was very much a formal affair then, with male passengers dressed in suits, and ladies in neck-to-ankle blouse and skirt ensembles and extravagant large hats. John Koh Collection.(Right) Dining Hall of a cruise ship belonging to the American President Lines c.1920s. Life on board the ship typically revolved around food and entertainment. Guests in the grand dining rooms would be treated to multi-course meals to the accompaniment of resident musical ensembles. John Koh Collection.

Between the 1900s and 1920s, social life on board ships became more varied as the ships became larger and social mores grew more relaxed. In the 1910s, male passengers would have been uncomfortably garbed in stiff suits, while ladies would be dressed in stifling corsets, and neck-to-ankle blouse and skirt ensembles with high boots and extravagant large hats. Interaction between the sexes would have been polite, guarded by modesty.

The Great War of 1914−18 swept away these inhibitions. Suddenly, men and women no longer dressed as conservatively, particularly the women, who started wearing the gauzy, flimsy flapper dresses that were all the rage in the 1920s. The Americans introduced larger cruise liners with more amenities − tennis courts, pool tables, even swimming pools on deck.

While social convention still held sway on land, once aboard these ships, no holds were barred. Affairs were commonplace; gossip, scandal and intrigue were the order of the day, and all these theatrics served to make the long journey more bearable and infinitely more memorable.

Life in the Grand Hotels

When the ships docked, Grand Hotels would take centrestage, and each city on the Grand Tour of the East boasted its own grande dame of the hospitality scene. The hotels were glorious, opulent establishments that catered to the fastidious needs of the Grand Tourists, who, having to travel for weeks or months at a time, often recreated their pampered lifestyles on board, complete with dozens of trunks of luggage and their favourite maids or man servants.

Each city on the Grand Tour of the East had its own grande dame of the hospitality scene. The hotels were glorious, opulent establishments that catered to the fastidious needs of the Grand Tourists who, having to travel for weeks or months at a time, often recreated their pampered lifestyles wherever they stayed. Pictured here is the majestic Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, India. Kennie Ting Collection.

Each city on the Grand Tour of the East had its own grande dame of the hospitality scene. The hotels were glorious, opulent establishments that catered to the fastidious needs of the Grand Tourists who, having to travel for weeks or months at a time, often recreated their pampered lifestyles wherever they stayed. Pictured here is the majestic Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, India. Kennie Ting Collection.Boasting “European style” amenities that included full suites with separate living/ dining, sleeping and washing areas, and the latest technologies like electricity and water closets (what flush toilets were called in those days), these establishments were more like homes away from home, rather than the hotels or guest-houses travellers today are more accustomed to. Guests would reside for weeks or months at a time, reading books, writing letters, entertaining guests or trading gossip.

Staying at one of these Grand Hotels became an integral part of the Grand Tour. Quite a few of the hotels became legendary destinations in their own right: the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay; Grand Hotel in Calcutta; Galle Face Hotel in Colombo; Strand Hotel in Rangoon; Raffles Hotel in Singapore; Hotel Des Indes in Batavia; Oriental Hotel in Bangkok; Hotel Continental in Saigon; Peninsula Hotel in Hong Kong; Cathay Hotel in Shanghai; Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, and the like.

All of these Grand Hotels became the centre of the colonial social circles of each city, catering to an almost exclusively European clientele – extremely wealthy Chinese and Southeast Asian nobility were also welcome – until World War II broke out. Every one of these hotels’ guest-lists read like a veritable who’s who of the time. Heads of state, royalty, taipans and business tycoons, socialites, celebrities and entertainers, even notorious gangsters and international criminals, featured in the histories that took place within these rarefied walls.

But it would fall to the writers and poets to immortalise the gilded lives that unfolded in these Far Eastern hotels at the turn of the century: Somerset Maugham, George Orwell, Noel Coward, Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad (to name but a few) in the Anglophone tradition; André Malraux, Pierre Loti and Marguerite Duras in the Francophone tradition; and Louis Couperus, E. du Perron and Robert Nieuwenhuys in the Dutch tradition.

Some of these writers had been born or lived significant parts of their lives in the Far East before returning to the West. Others undertook the Grand Tour of these countries and returned to recount the tale. Somerset Maugham, in particular, would famously establish a presence in many of the region’s legendary hotels, having travelled through almost all of the major Asian cities en route to the Pacific Islands. He would later meticulously document his experiences in numerous travel books, novels and stories, in particular his signature travelogue, The Gentleman in the Parlour: A Record of a Journey from Rangoon to Haiphong (1970).

Notable personalities linked to the Grand Hotels were not limited to guests alone. The remarkable Sarkies Brothers would have their name associated with a good half-dozen legendary hotels in the East, all in Southeast Asian cities. Originating from New Julfa, an Armenian enclave in the Persian city of Isfahan, the Sarkies brothers had each, in their turn, made their way to Southeast Asia, by way of British India.

There were four brothers: Martin, the eldest, was the first to arrive in Malaya, but it was Tigran, the second brother with an entrepreneurial streak, who co-founded with Martin in 1885 the company Sarkies Brothers and established the Eastern & Oriental (E & O) Hotel in Penang that same year. This was followed by the Raffles Hotel in Singapore two years later. Aviet, the third brother, would establish the Strand Hotel in Rangoon in 1901, while the youngest brother, Arshak, would take over the reins of managing the E & O in Penang, becoming the brother who was most indelibly linked to that establishment.

(Left) The Sarkies Brothers from New Julfa, an Armenian enclave in the Persian city of Isfahan, owned luxury hotels in the major Southeast Asian cities. These included the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, the Strand Hotel in Rangoon, and the E & O and Crag hotels in Penang. Staying at one of these Grand Hotels became an integral part of the Grand Tour, with these lodgings serving as homes away from home for the Grand Tourists. Kennie Ting Collection.

(Left) The Sarkies Brothers from New Julfa, an Armenian enclave in the Persian city of Isfahan, owned luxury hotels in the major Southeast Asian cities. These included the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, the Strand Hotel in Rangoon, and the E & O and Crag hotels in Penang. Staying at one of these Grand Hotels became an integral part of the Grand Tour, with these lodgings serving as homes away from home for the Grand Tourists. Kennie Ting Collection.(Right) A view of the Manila Hotel in Manila, the Philippines, from the river. The hotel still stands today and has been refurbished to its former glory. Kennie Ting Collection.

By the early 1900s, the Sarkies Brothers were the leading hoteliers in the East, counting, among their properties, not just the Raffles, the E & O and the Strand, but also the Crag Hotel in Penang, and the Seaview Hotel and the Raffles Tiffin Room in Singapore. A cousin managed the Adelphi Hotel in Singapore – yet another grand hotel establishment. In the meantime, a Javanese branch of the Sarkies family was established, headed by Martin’s son, Lucas Martin Sarkies, who would go on to helm the fabled Oranje Hotel (today’s Hotel Majapahit) in the port city of Soerabaja – Java’s great metropolis.

The Malayan branch of Sarkies Brothers would go bankrupt in 1931, in the thick of the Great Depression and following Arshak’s tragic and untimely death of a heart attack at Penang’s E & O Hotel. Management of all their hotels would pass out of the family’s hands, with the exception of the Oranje, which continued to be managed by Lucas Martin Sarkies and his descendants until the 1960s.

Thankfully, these Grand Hotels established by the Messrs Sarkies and their relatives have miraculously withstood the test of time and continue to receive guests today in the cities of Penang, Yangon, Surabaya and Singapore. Restored to their former splendour, these edifices are a living testament to the glory days of travel to the East of Suez.

Kennie Ting is the Director of the Asian Civilisations Museum and Group Director of Museums at the National Heritage Board. He is the author of the book, The Romance of the Grand Tour: 100 Years of Travel in South East Asia which explores the colonial heritage of Southeast Asian port cities and the history of travel to the East.

Kennie Ting is the Director of the Asian Civilisations Museum and Group Director of Museums at the National Heritage Board. He is the author of the book, The Romance of the Grand Tour: 100 Years of Travel in South East Asia which explores the colonial heritage of Southeast Asian port cities and the history of travel to the East.

REFERENCES

Artmonsky, R., & Cox, S. (2012). P & O: Across the oceans, across the years. UK: Antique Collectors’ Club. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Berneron-Couvenhes, M. (2007). Les Messageries Maritimes – L’essor d’une grande compagnie de navigation française, 1851–1894. Paris: Presses de l’Université Paris-Sorbonne. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Bird, I. L. (1967). The golden chersonese and the way thither. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 BIS)

Conrad, J. (1900). Lord Jim. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg website.

Conrad, J. (1917). The shadow-line: A confession. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg website.

Couperus, L. (1922). The hidden force (De stille kracht). London: J. Cape. (Call no.: RSEA 833.3136 COU)

Coward, N. (2002). Mad dogs and Englishmen. In The Noel Coward songbook [Sound recording]. New York: EMI Classics. (Call no.: 782.14 COW-ART])

Crawfurd, J. (1830). Journal of an embassy from the governor-general of India to the courts of Siam and Cochin-China; exhibiting a view of the actual State of these kingdoms. London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. (Microfilm no.: NL 11335)

Deakes, C., & Stanley, T. (2013). A century of sea travel: Personal accounts from the steamship era. UK: Seaforth Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Du Perron, E. (1984). Country of origin (Het land van herkomst). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 839.3136219 PER)

Duras, M. (1985). The lover (L’Amant). New York: Pantheon Books. (Call no.: RSEA 843.912 DUR)

Fletcher, R. A. (1913). Travelling palaces: Luxury in passenger steamships. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

Greene, G. (1955). The quiet American. New York: Viking Press. (Call no.: RDET 823.912 GRE)

Kipling, R. (1892). Mandalay. In R. Kipling. (1892), Barrack-room ballads, and other verses. London: Methuen Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Liu, G. (2006). Raffles Hotel. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q915.9570613 LIU-[TRA])

Loti, P. (1999). A pilgrimage to Angkor (Un pèlerin d’angkor). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, (Call no.: RSEA 915.9604 LOT-[TRA])

Malraux, A. (1961). The royal way (La voie royale). New York: Random House. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Maugham, W. S. (1953). The casuarina tree: Six stories. London: W. Heinemann. (Call no.: RCLOS 823.91 MAU)

Maugham, W. S. (1930). The gentleman in the parlour: A record of a journey from Rangoon to Haiphong. London: William Heinemann Ltd. (Call no.: RSEA 959 MAU)

Meade, M., Fitchett, J., & Lawrence, A. (1987). Grand Oriental hotels: From Cairo to Tokyo, 1800–1939. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. (Call no.: RSING 647.95401 MEA)

Niewenhuys, R. (1982). Faded portraits. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 839.31364 NIE)

Nieuwenhuys, R. (1999). Mirror of the Indies: A history of Dutch colonial literature (Oost-Indische Spiegel). Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. (Call no.: RDET 839.31099598 NIE)

Orwell, G. (2014). Burmese days. London: Penguin Classics. (Call no.: RSEA 823.912 ORW)

Sarraut, A. (2010). Indochina. Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus. (Call no.: RSEA 959.703 SAR)

Sharp, I. (2008). The E & O Hotel: Pearl of Penang. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSEA 915.95106 SHA-[TRA])

Ting, K. (2015). The romance of the grand tour: 100 years of travel in South East Asia. Singapore: Talisman Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 915.9 TIN-[TRA])

NOTES

-

Kipling, R. (1892). Mandalay. In R. Kipling. (1892), Barrack-room ballads, and other verses. London: Methuen Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩