A History of Singapore Horror

Singaporeans have always had a morbid fascination with the supernatural. Ng Yi-Sheng examines the culture of horror in our oral folklore, books and films.

An illustration of Hantu Puteri (Ghost Princess) by A. F. Anthony. All rights reserved, McHugh, J. N. (1959). Hantu Hantu: An Account of Ghost Belief in Modern Malaya (2nd edition) (p.45). Singapore: Published by Donald Moore for Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.3 MAC).

An illustration of Hantu Puteri (Ghost Princess) by A. F. Anthony. All rights reserved, McHugh, J. N. (1959). Hantu Hantu: An Account of Ghost Belief in Modern Malaya (2nd edition) (p.45). Singapore: Published by Donald Moore for Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.3 MAC).In 2016, I was asked to speak at a Singapore Writers Festival panel discussion titled “SG HORROR: Who’s Afraid of the Dark”. This surprised me, since I had never identified myself as a horror writer. Nor had my two co-panellists, Audrey Chin and Jon Gresham. The very purpose of the event was, apparently, to ponder “why there are so few horror writers in Singapore”.

Frankly, this infuriated me. The panel’s premise was absurd: not only does Singapore have a plethora of horror writers; we also have a rich and layered culture of horror that has been interpreted by a diverse range of storytellers over the centuries. I cobbled together a hastily researched lecture on the subject. Additionally, I invited a real-life horror writer to join the discussion: Raymus Chang, author of the short story collection Shadows from Here: Tales of Terror (2016).

That lecture forms the basis of this essay: an exploration of Singapore’s horror heritage over the ages. Certain gaps remain: I’ve been unable to gather much data on the history of horror in radio and non-English literature for instance. Nevertheless, it is possible to sketch a timeline that helps us understand the roots of Singaporean horror, how it has evolved, and where it is headed in the future.

Folk Horror (1810s–1940s)

The very beginnings of modern Singaporean history are tinged with horror. In 1819, shortly after Singapore was established as a British trading post, Stamford Raffles called for an expedition to climb Fort Canning Hill, then called Bukit Larangan, which means “The Forbidden Hill” in Malay. When the Temenggong’s men warned him that “none of us have the courage to go up that hill because there are many ghosts on it. Every day one can hear on it sounds as of hundreds of men. Sometimes one hears the sound of heavy drums and of people shouting”, Raffles was reported to have scoffed, saying, “I should like to see your ghosts”.1

Other settlers who soon arrived on the island brought their supernatural traditions with them: tales of yau gwee (hungry ghosts in Hokkien) from China, hantu (ghost in Malay) from the Malay Archipelago, mohini (vengeful female spirits) from the Indian subcontinent, and jinn (spirits) from the Arab world. These immigrant beliefs soon took root in the local landscape. For instance, in 1843, it was reported that the Chinese living in the Tanglin area especially feared tiger attacks as they believed victims would become the ghostly slaves of these animals.2 In 1856, it was rumoured that St Andrew’s Cathedral had been overrun by evil spirits. Gossipmongers claimed that these vicious spirits could only be pacified with sacrifices of human heads, and that the British were ordering Indian convicts to harvest them from hapless passers-by.3

Colonialism brought with it a wave of British ethnographers, with Singapore featuring as a popular port-of-call in their surveys of the greater Malay world. Descriptions of hantu and bomoh (Malay shamans) abound in their writings, such as John Turnbull Thomson’s Glimpses into Life in Malayan Lands (1864), Frank Swettenham’s Malay Sketches (1895) and Walter Skeat’s Malay Magic (1900). These works provide valuable insights into the early folk beliefs of the Malay community.

An anchak or sacrificial tray used by the Malay medicine man (or bomoh) for occult practices. The tray has a fringe around it called “centipedes’ feet”. The ketupat and lepat (rice receptacles made of plaited palm fronds) are hung from the “suspenders” attached to the tray. All rights reserved, Skeat, W. W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (p. 414). London: Macmillan and Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession nos.: B02930611K; B29267256F).

An anchak or sacrificial tray used by the Malay medicine man (or bomoh) for occult practices. The tray has a fringe around it called “centipedes’ feet”. The ketupat and lepat (rice receptacles made of plaited palm fronds) are hung from the “suspenders” attached to the tray. All rights reserved, Skeat, W. W. (1900). Malay Magic: Being an Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula (p. 414). London: Macmillan and Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession nos.: B02930611K; B29267256F).By the early 20th century, it was evident that horror was becoming the stuff of mass entertainment. In 1923, when New World amusement park opened in Jalan Besar, it featured a highly popular ghost train ride through a darkened enclosure filled with ghoulish images. Great World park in Kim Seng Road would follow suit in 1929 with a similar ride. Though both have since been demolished, old photographs suggest that the train rides featured images of ghosts and demons inspired by Chinese folklore.4

Thankfully, one splendid artefact of early Chinese horror still survives in Pasir Panjang: the Ten Courts of Hell in Haw Par Villa, built in 1937 and originally known as Tiger Balm Gardens. Visitors today can still wander among garishly painted dioramas of naked souls being tortured by demons in the afterlife.

Diorama featuring hapless souls being tortured in the afterlife at Haw Par Villa’s Ten Courts of Hell. Photo by David Shamma, 22 March 2014. Courtesy of Flickr.

Diorama featuring hapless souls being tortured in the afterlife at Haw Par Villa’s Ten Courts of Hell. Photo by David Shamma, 22 March 2014. Courtesy of Flickr.Malayan Horror (1950s–1970s)

At midnight on 27 April 1957, Cathay-Keris Productions premiered a film that would forever be etched into the Singaporean psyche. Titled Pontianak, it told the story of the eponymous pontianak, the infamous long-haired female vampire from Malay mythology. Traditionally, this creature is said to be the vengeful spirit of a woman who had died during childbirth. However, the film took liberties with the source material, reimagining its heroine Chomel as an innocent wife who becomes a homicidal monster due to a powerful curse.

Pontianak was a massive success, screening in major cinemas for almost two months − an unusually long period for homegrown films of the era. Although Pontianak is remembered as a Malay film in the popular imagination, it was in fact a multiethnic collaboration directed by B.N. Rao, written by Abdul Razak and produced by Ho Ah Loke. The film was initially released in both Malay and Mandarin, and later dubbed into Cantonese and English for overseas audiences. As a result, the pontianak tale is fondly remembered by people of all races in Malaysia and Singapore.

The film marked the birth of Malay horror as a film genre. To capitalise on the film’s success, Rao directed three sequels in quick succession: Dendam Pontianak (Revenge of the Pontianak) in 1957; Sumpah Pontianak (Curse of the Pontianak) in 1958; and Pontianak Gua Musang (The Vampire of the Civet Cat Cave) in 1964. Cathay-Keris’ main rival, Shaw Brothers, responded with its own trilogy, directed by Ramon Estella from the Philippines: Anak Pontianak (Son of the Pontianak) in 1958; Pontianak Kembali (The Pontianak Returns) in 1963; and Pusaka Pontianak (The Pontianak Legacy) in 1965.

Maria Menado as the pontianak, a female vampire from Malay mythology, in B.N. Rao’s 1957 Dendam Pontianak. © Dendam Pontianak. Directed by B. Narayan Rao and produced by Cathay-Keris Films, 1957.

Maria Menado as the pontianak, a female vampire from Malay mythology, in B.N. Rao’s 1957 Dendam Pontianak. © Dendam Pontianak. Directed by B. Narayan Rao and produced by Cathay-Keris Films, 1957.Other ghoulish monsters from Malay folklore also made their way to the silver screen. K.M. Basker’s Hantu Jerangkung (1957) dealt with a female “skeleton ghost”. L. Krishan’s Orang Minyak, Serangan Orang Minyak and Sumpah Orang Minyak (all released in 1958) featured a supernatural “oily man” who sexually assaults women – memorably played by a young P. Ramlee in Sumpah Orang Minyak. There was even a horror-themed comedy film: Mat Sentol’s Mat Toyol (1969), featuring a toyol, a child-sized spirit used by a Malay shaman as a servant.

Interestingly, this deluge of horror began in 1957, the same year the Federation of Malaya Independence Act took effect. “Were people really so anxious about self-governance, or saw it as a kind of existential horror, that they suddenly thought of ghosts and demons?” asks Malaysian filmmaker Amir Muhammad. “I doubt if they were that morbid. I think the horror genre is a sign of confidence, because it’s a bold step to take stories that had existed only orally and then use technology to bring them to life. It’s an assertion of narrative (and cultural) independence.”5

Amir is in fact mistaken in his assertion that Malay ghost stories existed only in oral form before Pontianak was produced. A brief flowering of horror fiction had taken place from 1952 to 1956, thanks to two men who would later become key politicians. These men were the future President of Singapore, Yusof bin Ishak, and the future Cabinet Minister, Othman Wok, then employed as a journalist at the Malay newspaper Utusan Melayu. “Malays just love stories like these and Yusof Ishak asked me to write one every week for the Sunday edition called Utusan Zaman,” Othman later recalled. “Sure enough, the circulation almost tripled.”6

These tales, later published in English under the title Malayan Horror, display a remarkably contemporary view of the supernatural as characters from modern times are confronted not only by Malay spectres but also by those from other cultures. In “The Anklets”, a mortuary doctor sees the disembodied feet of a murdered Indian woman; in “Visitor from the Coffin”, a photographer snaps photographs of the ghost of a Chinese grocer; and in “The Guardian”, an archaeologist’s assistant is hunted down by a Dayak mummy.7

The Malayan horror craze may have influenced the English literary horror scene as well. J. N. McHugh’s study of Malay spirits, Hantu Hantu: An Account of Ghost Belief in Modern Malaya (1959), is essentially an ethnographic work, yet its illustrations and accessible style have made it a cult favourite among nonacademic readers in Singapore. Likewise, there is Malay supernatural imagery aplenty in Gregory Nalpon’s work (regardless that he was an Indian Catholic), in short stories such as “The Spirit of the Moon” and “The Mango Tree”, written between the 1950s and 70s, and later published in his posthumous collection The Wayang at Eight Milestone. Critics have suggested that such works may be regarded as “examples of an early postcolonial Singapore gothic”.8

Sadly, following Singapore’s expulsion from Malaysia in 1965, local culture underwent a radical change. Singapore lost its position as the hub of the Malay film industry, and Shaw and Cathay-Keris moved their operations to Kuala Lumpur. With the lingua franca of Singapore shifting from Malay to English, Singapore was no longer the centre of Malay cultural production. The age of Malayan horror had come to an end.

Singaporean Horror (1980s–early 2000s)

Today, Catherine Lim is widely known as the author of social-realist short stories and feminist novels. Yet I believe she has another, more obscure role in our literary history as the Mother of Singaporean Horror. In her early writings, Lim documents the influence of the Chinese spiritual world on the psyche of modern Singaporeans. This helped to lay the groundwork for the rebirth of our horror culture, and its transformation from a specifically Malay milieu to a multiethnic one.

Lim first referenced the uncanny in her short story collection Or Else the Lightning God and Other Stories (1980) with subtle mentions of hauntings in “Unseeing”, “The Bondmaid” and “Or Else the Lightning God”. She followed this with They Do Return… But Gently Lead Them Back (1983), possibly Singapore’s first English-language collection of horror stories. These tales range from ethnographic descriptions of traditional lore to more contemporary yarns. For instance, “A Boy Named Ah Mooi” explains how sons may be protected from demons by disguising them as girls, while “Lee Geok Chan” describes how a dead student mysteriously returns to complete her A-Level exams.

Did Lim’s books directly lead to a boom in local horror? It is hard to say as later horror writers do not cite her as an influence. Nevertheless, by the late 1980s, countless volumes of ghost stories were flying off the presses, including Nicky Moey’s Sing a Song of Suspense (1988), Goh Sin Tub’s Ghosts of Singapore (1990), Lim Thean Soo’s Eleven Bizarre Tales (1990), Z. Y. Moo’s The Weird Diary of Walter Woo (1990), K. K. Seet’s Death Rites (1990), Lee Kok Liang’s Death is a Ceremony and Other Short Stories (1992), Rahmad bin Badri’s Ghostly Tales from Singapore (1993) and V. Mohan’s Spooky Tales from Singapore (1994). There was even a horror comic series: Souls (1989−1995), edited by K. Ramesh and Ramesh Kula.

Undoubtedly, the biggest name of the era was Russell Lee. In 1989, he released The Almost Complete Collection of True Singapore Ghost Stories, a compilation of 50 supposedly real-life accounts of paranormal encounters gathered from ordinary Singaporeans. It was a major hit, selling an unprecedented 30,000 copies in just over two months.9 Lee cashed in on his success by transforming the standalone book into a series. Today, True Singapore Ghost Stories (1989–present) comprises 25 volumes, with the author aiming to reach Book 50 within his lifetime.10

Damien Sin has published four volumes of his Classic Singapore Horror Stories while Russell Lee’s True Singapore Ghost Stories is already into its 25th volume. Both series are huge hits with horror fans in Singapore. All rights reserved, Angsana Books.

Damien Sin has published four volumes of his Classic Singapore Horror Stories while Russell Lee’s True Singapore Ghost Stories is already into its 25th volume. Both series are huge hits with horror fans in Singapore. All rights reserved, Angsana Books.True Singapore Ghost Stories may be pulp literature, but it is also thoroughly representative of Singapore’s diversity. Its spirits hail from a range of cultural backgrounds: readers are transported from a tale of a pontianak in a banana tree to one of demon possession in a church.11

Occasionally, hauntings even cross ethnic lines, such as when a Chinese boy is cursed by a Javanese bracelet.12 From Book 4 onwards, these accounts are interspersed with chapters titled “Russell Lee Investigates”, expounding on the afterlife in world religions, beliefs about vampires, cults, UFO sightings and other topics – arguably a form of transcultural education. Interestingly, Lee himself is an enigmatic and racially ambiguous figure: to protect his anonymity, he has routinely appeared at events in a black mask and gloves, obscuring even the colour of his skin.

Another prolific author is Pugalenthii, aka Pugalenthi Sr, founder of the publishing company VJ Times. While editing the horror anthology Black Powers (1991), he decided to write a few stories himself. This marked the beginning of a formidable literary career: he now has dozens of titles to his name, including Evil Eyes (1992), Rakasa (1995), and the Nightmares series (1996−2003), a collection of ghost stories exploring various haunted locales in Singapore, including schools, hospitals, army camps and offices. According to the author, this last series was so popular it was used in Malaysia as an English teaching resource.13

The most skilled Singaporean horror writer of the period, however, is probably the late Damien Sin. The four volumes of his Classic Singapore Horror Stories series (1992–2003) belong to the genre of horror, but display a firm command of plot and character as well as a deft hand in describing Singapore’s sordid underbelly. What stays with the reader, however, is the bloodcurdling viscerality of his tales, such as “Sealed with a Kiss”, in which the ghost of a sex worker literally rips out the heart of her pimp with her tongue.

An illustration from the story “Suffer the Children” in Damien Sin’s Classic Singapore Horror Stories (Book 1) . All rights reserved, Sin, D. (1992). Classic Singapore Horror Stories (p. 74). Singapore: Flame of the Forest. (Call no.: RSING S823 SIN)

An illustration from the story “Suffer the Children” in Damien Sin’s Classic Singapore Horror Stories (Book 1) . All rights reserved, Sin, D. (1992). Classic Singapore Horror Stories (p. 74). Singapore: Flame of the Forest. (Call no.: RSING S823 SIN)Amidst these spooky tales, the genre of crime horror also flourished. In 1981, Singapore was stunned by news reports revealing that a spirit medium named Adrian Lim and his two wives had murdered two children in a bizarre act of human sacrifice. This atrocity provoked writers to create a number of popular nonfiction works about local crime, such as N.G. Kutty’s Adrian Lim’s Beastly Killings (1989), Alan John’s Unholy Trinity (1989) and Sumiko Tan’s True Crime (1990).

These texts are important because they are linked to the rebirth of Singapore’s horror cinema, which had been dormant since the 1960s. It would take almost 25 years before the first Singaporean full-length horror movie in English would be released locally. This was Arthur Smith’s Medium Rare (1991), inspired by the Adrian Lim murders. Six years later, another cinematic version of the infamous murders appeared: Hugo Ng’s God or Dog (1997). Around the same time, Eric Khoo’s violent drama Mee Pok Man (1995) featured a script written by horror author Damien Sin: a very loose retelling of his short story “One Last Cold Kiss”.

Supernatural horror found its way back into cinema soon after. Fittingly, the first work in this new wave of films was a tribute to the classic Malay horror movie: Djinn Ong’s Return to Pontianak (2001), in which a team of trekkers encounters a pontianak in an abandoned village. Kelvin Tong chose to explore Chinese horror in The Maid (女佣; 2006), depicting the ordeals of a Filipina domestic worker during the Hungry Ghost Festival. Even horror comedy made a comeback, with works like Tong’s Men in White (鬼啊!鬼 啊!; 2007), and Jack Neo and Boris Boo’s Where Got Ghost? (吓到笑; 2009).

Television likewise embraced horror elements in its programming, even as Mediacorp’s early shows were inspired more by foreign horror traditions than our own. For instance, Channel 8 created Immortal Love (不老传说; 1997), a soap opera about 19th-century Singaporeans being transformed into jiangshi or Chinese vampires − creatures made famous by Hong Kong films rather than local folklore. At the same time, Channel 5 produced Shiver (1997), an anthology series patterned after the Western classic The Twilight Zone, featuring bizarre plots about time travel and werewolves.

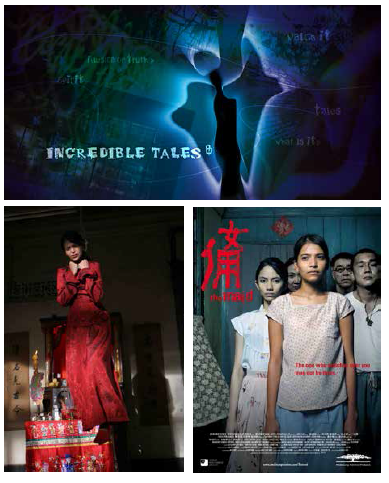

Homegrown horror would eventually take over the small screen too with Channel 5’s Incredible Tales (2005–2013), an anthology series based on local horror narratives. Mediacorp would also commission Esan Sivalingam’s TV movie Pulau Hantu (2008), which tackled ghost stories in army camps.

(Above) Incredible Tales, an anthology series based on local horror narratives, was screened on Mediacorp’s Channel 5 from 2005 to 2013. Courtesy of Mediacorp.

(Above) Incredible Tales, an anthology series based on local horror narratives, was screened on Mediacorp’s Channel 5 from 2005 to 2013. Courtesy of Mediacorp.(Top) Film still and movie poster from Kelvin Tong’s The Maid (女佣; 2006). The film is about a newly arrived Filipino domestic worker in Singapore who encounters supernatural forces during the Chinese seventh lunar month. Courtesy of Mediacorp.

Interestingly, Mediacorp writers of the 1990s had unwittingly foreseen a future trend in our horror scene. Singaporeans had a longing to be haunted, not only by their own ghosts, but also by the spectres of foreign lands.

Cosmopolitan Horror (2000s–present)

In 2009, a new best-selling Singaporean horror series hit the shelves, marketed specifically at children. The Mr Midnight series (2009–present) is the work of James Lee, the pen name of Jim Aitchison – author of the raunchy Sarong Party Girl comic books (1994–96) as well as the lyrics of the National Day songs, “One People, One Nation, One Singapore” (1990) and “The Singapore Story” (1998).

Surprisingly, the 109 volumes of Mr Midnight display few hallmarks of local horror. The protagonists may be Singaporean children, but their paranormal foes are the stuff of Hollywood: Egyptian mummies, killer clowns, murderous robots, haunted pumpkins, monstrous Santa Clauses and the like.

One could claim this is due to Aitchison’s Australian origins. Yet the truth is, a number of recent Singaporean storytellers too have embraced Hollywood horror in their creations. S.M. De Silva’s Blood on the Moon (2010) describes a young Singaporean’s voyage to a city full of vampires and werewolves. Nicholas Yong’s Land of the Meat Munchers (2013) and Ryan Loh’s Dead Singapura (2016) envision our city in the midst of a zombie apocalypse. Angie Child’s The Regenerator (2015) deals with alien invaders in the future – the 23rd century no less.

Among filmmakers, even Kelvin Tong, once so obsessed with Chinese ghosts, has now turned his sights to the West. His latest movie, The Faith of Anna Waters (2016), deals with an American family in Singapore confronting a Christian-style demonic suicide cult. A more complicated set of cultural issues surrounds Gilbert Chan’s 23:59 (2011) and Ghost Child (鬼仔; 2013). These two films draw on the classic local tropes of army camp ghost stories and toyol hauntings respectively. Yet both films feature all-Chinese casts − an offensive act of erasure given the original ethnic roots of these tales.

So, are we in danger of losing our horror heritage? Probably not. There are still plenty of publications featuring local spooks, including Andrew Lim’s Tales from the Kopitiam series (2008–09), Verena Tay’s Spectre (2012) and the Spooked in Singapore series (2014–15), ostensibly written by “the team of exorcists from Ghostbuster Singapore”.

The most ambitious of these books is probably Sandi Tan’s The Black Isle (2012). The novel retells the story of Singapore through the eyes of the spirit medium Cassandra, who exerts her dark influence on the island throughout its history, from the time of British colonialism and the Japanese Occupation to the Communist Emergency, Konfrontasi and Independence.

Otto Fong’s Bitter Suites (2013) is noteworthy for both its originality and its gore: it features a curse on social media, condemning its victims to suffer the tortures of Chinese hell as depicted in Haw Par Villa. Younger readers may prefer Zed Yeo’s Half Ghost (2016), about a half-human, half-vampire boy named Nail who battles a pontianak in the underworld.

Also of interest is Nuraliah Norasid’s The Gatekeeper (2017), winner of the Epigram Books Fiction Prize. The author cunningly combines the Medusa Greek mythology with Malay legends, yielding the tale of Ria, a serpent-haired girl who communes with jungle spirits.

Ultimately, we may be able to sustain a horror culture that balances foreign and local monsters. To fathom this, one need only consider the phenomenon of Universal Studios Singapore’s Halloween Horror Nights, an annual festival of horror held since 2011. As might be expected of an American-owned entity, the event features actors playing creepy characters straight out of Hollywood: vampires, aliens, witches, serial killers and clowns. Interspersed with these are a few scares inspired by non-American cultures: Chinese fox fairies, Japan’s Suicide Forest and the Mexican Day of the Dead.

Universal Studios Singapore’s Halloween Horror Nights is an annual festival of horror held since 2011. The event features actors playing creepy characters straight out of Hollywood: vampires, aliens, witches, serial killers and clowns. Interspersed with these are a few scares inspired by non-American cultures, such as Chinese fox fairies, Japan’s Suicide Forest and the Mexican Day of the Dead. Courtesy of Dejiki.com.

Universal Studios Singapore’s Halloween Horror Nights is an annual festival of horror held since 2011. The event features actors playing creepy characters straight out of Hollywood: vampires, aliens, witches, serial killers and clowns. Interspersed with these are a few scares inspired by non-American cultures, such as Chinese fox fairies, Japan’s Suicide Forest and the Mexican Day of the Dead. Courtesy of Dejiki.com.However, amidst these imported ghouls are refreshingly local elements. Visitors witness zombie outbreaks in HDB blocks and hawker centres; they walk into recreations of Chinese funerals, Malay graveyards, World War II hospitals, army camps and MRT tracks; and they encounter familiar phantoms from our multiethnic culture – the hungry ghost, the toyol and the pontianak.

Perhaps the last word on our horror heritage should go to Alfian Sa’at. As an author who once scorned works like True Singapore Ghost Stories, he now confesses a new-found respect for these writings as a form of national literature; the oral folklores of multiple races meshing as one, teaching us superstitions and taboos from each other’s cultures and traditions.

“One does not need to be Malay to know what a Pontianak is. One does not have to believe in any religion to entertain the possibility of demonic possession. One does not have to be a Taoist to know that it is somewhat taboo to mess around with Hungry Ghost offerings… [T]his circulation and borrowing of beliefs was hardly self-conscious, and a demonstration of a kind of grassroots interculturalism… If multiculturalism is about respecting other people’s beliefs, interculturalism goes further, to the point of adopting these beliefs. Even if this was about hedging bets against the spiritual world… Hantulah Singapura…”14

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and journalist. His books include his debut poetry collection last boy, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008, the bestselling SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the movie novelisation Eating Air and the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience. He tweets and Instagrams at @yishkabob.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and journalist. His books include his debut poetry collection last boy, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008, the bestselling SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the movie novelisation Eating Air and the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience. He tweets and Instagrams at @yishkabob.

NOTES

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir. (2009). The Hikayat Abdullah (A. H. Hill, Trans.) (p. 146). Kuala Lumpur: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5 ABD). [Note: Abdullah claims that Colonel William Farquhar organised the expedition; later historians establish that it was almost certainly Raffles. See Hahn, E. (1968). Raffles of Singapore (pp. 463–464). London: Oxford University Press Kula Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.570210924 RAF)] ↩

-

Tigers. (1843, October 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (pp. 575–576). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUS) ↩

-

Singapore Press Holdings. (1953, February 19). Round-up of the three amusement parks – New World, Happy World, Great World: This ‘monster’ is one of the thrills of the Ghost Ride in the amusement park [Photograph]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Amir Muhammad. (2010). 120 Malay movies (p. 14). Petaling Jaya: Matahari Books. (Call no.: RSEA 791.430899923 AMI) ↩

-

Chandy, G. (2000, April 23). Once an MP, now he’s a ‘JC’. The New Paper, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Othman Wok. (1991). Malayan horror: Macabre tales of Singapore and Malaysia in the 50’s. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING S899.2305 OTH) ↩

-

Whitehead, A. (2013). Introduction to The Wayang at Eight Milestone: Stories & essays by Gregory Nalpon (p. xvii). Singapore: Epigram Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

A runaway bestseller. (1989, December 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sukmawati Umar. (2015, October 9). Inspiring chills at Halloween Horror Nights. The New Paper. Retrieved from The New Paper website. ↩

-

Lee, R. (1992). The almost complete collection of true Singapore ghost stories (Book 2) (pp. 20–23). Singapore: Flame of the Forest. (Call no.: RSING LEE) ↩

-

Lee, R. (1994). The almost complete collection of true Singapore ghost stories (Book 3) (pp. 19–22). Singapore: Angsana Books. (Call no.: RSING LEE) ↩

-

Interview with Pugalenthii, 25 March 2017. ↩

-

Alfian Sa’at. (2017, January 19). Some thoughts which I shared at last night’s forum on Singapore literature (paraphrased and expanded). Retrieved from Facebook. ↩