Sci-Fi in Singapore: 1970s to 1990s

The sci-fi frenzy took off in Singapore in 1978 when Star Wars was screened at cinemas here. Nadia Arianna Bte Ramli looks at sci-fi works produced between 1970s and 1990s.

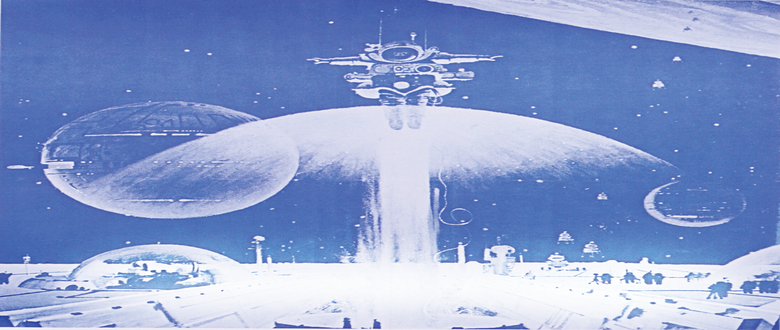

Part of the publicity poster for the 1979 Science Fiction Short Story Competition organised by the Rotary Club of Jurong, Singapore Science Centre and Society of Singapore Writers. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Part of the publicity poster for the 1979 Science Fiction Short Story Competition organised by the Rotary Club of Jurong, Singapore Science Centre and Society of Singapore Writers. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The popularity of contemporary science fiction publications, such as LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction (2013–), The Ayam Curtain (2012) and The Steampowered Globe (2012),1 point towards a sizable and growing base of readers who are fans of this genre of literature.

LONTAR, which published its eighth issue in April 2017, is a biannual literary journal featuring science fiction as well as fantasy, alternative histories and tales of the supernatural. The Ayam Curtain is similarly an anthology of speculative fiction envisioning what Singapore could be or might have been, while The Steampowered Globe by the Happy Smiley Writers Group is a collection of seven “steampunk” stories, a relatively new subgenre of science fiction that focuses on technology, specifically the industrial steam-powered machinery of the 19th century.

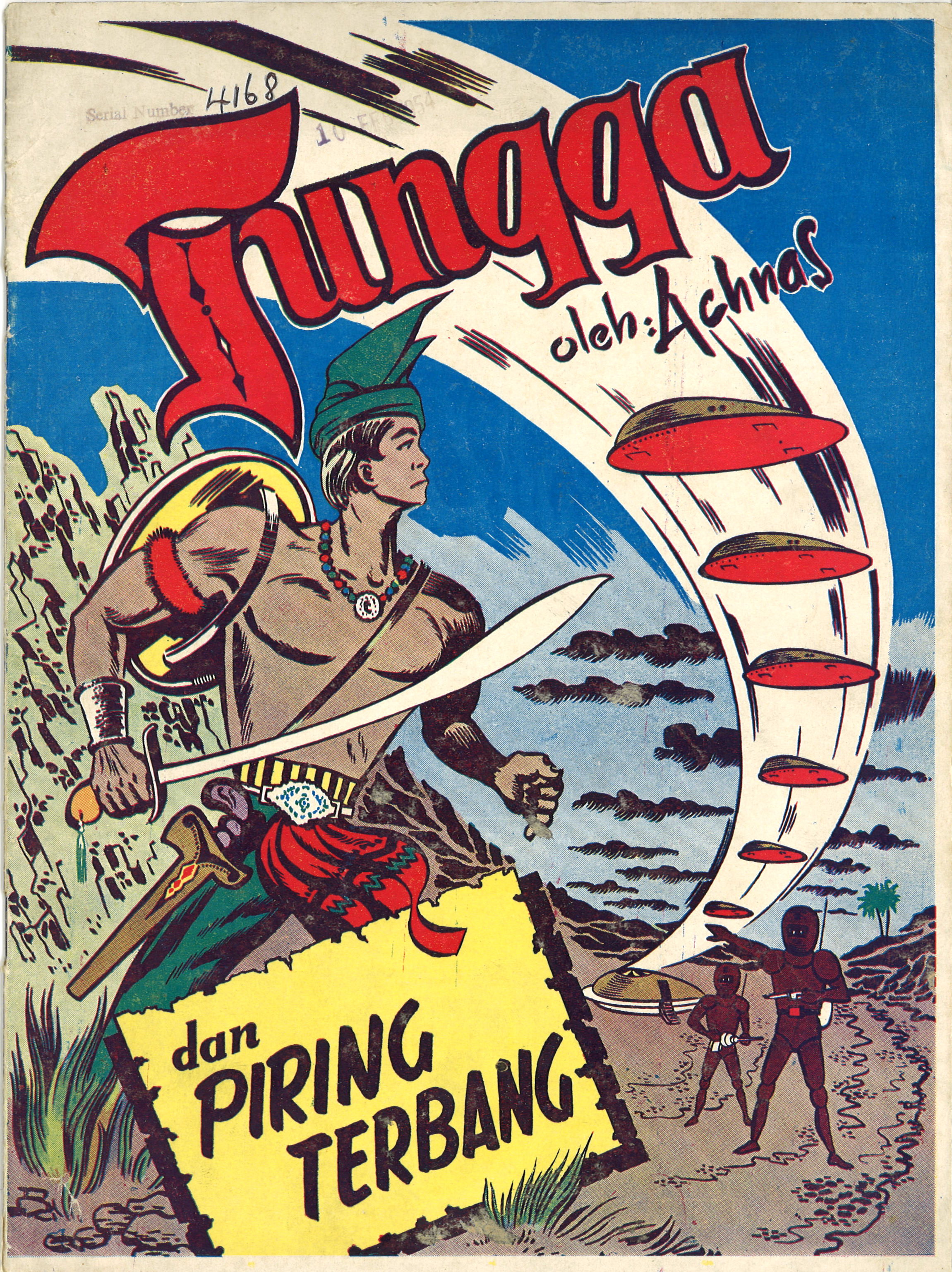

But when exactly did science fiction take off in Singapore? The genre is certainly no stranger to the Malayan literary scene; one of the earliest sci-fi publications on record dates back to 1953, when a Malay comic series released a sci-fi issue titled Tungga dan Piring Terbang (Tungga and the Flying Saucer). Published by the Malayan Indonesian Book and Magazine Store (MIBS) in Singapore, it was created by Indonesian comic artist Naz Achnas.2

Published in 1953, Tungga dan Piring Terbang (Tungga and the Flying Saucer) is one of the earliest sc-fi publications on record in Singapore. The Malay comic series was created by Indonesian comic artist Naz Achnas. All Rights Reserved, Naz Achnas. (1953). Tungga dan Piring Terbang, Singapore: MIBS. Available via PublicationSG.

Published in 1953, Tungga dan Piring Terbang (Tungga and the Flying Saucer) is one of the earliest sc-fi publications on record in Singapore. The Malay comic series was created by Indonesian comic artist Naz Achnas. All Rights Reserved, Naz Achnas. (1953). Tungga dan Piring Terbang, Singapore: MIBS. Available via PublicationSG.Other local sci-fi comics followed in subsequent decades, such as The Valiant Pluto-Man (1982), The Amazing Adventures of Captain V (1988) and The Sunday Times comics: “The Huntsman”(1992) and “Speedsword and the Doomsday Pearl” (1991).3

Sci-fi Takes Off

Sci-fi picked up pace from the late 1970s onwards when Hollywood films such as George Lucas’s Star Wars and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind made their way to Singapore cinemas in 1978.4 In turn, sales of sci-fi titles based on these blockbuster films and hit television series, such as Space 1999 and the cult favourite Star Trek, enjoyed a sharp spike in sales at local bookshops. In 1978, MPH Bookstores reported that sales of its other sci-fi titles – including books by noted authors of the genre such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke – shot up by at least 50 percent that year.5

Science fiction in Singapore picked up pace from the late 1970s when Hollywood films such as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, made their way to local cinemas in 1978. The Straits Times, 15 January 1978, p 12.

Science fiction in Singapore picked up pace from the late 1970s when Hollywood films such as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, made their way to local cinemas in 1978. The Straits Times, 15 January 1978, p 12.This growing readership continued well into the 1980s, with Times bookshop at Centrepoint quadrupling its shelf space for sci-fi and fantasy titles between 1984 and 1988. Sci-fi maintained its presence in Singapore with the release of two sequels to Star Wars in 1980 and 1983 respectively and other box-office successes like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Blade Runner (1982) and Star Trek IV (1986). In 1988, MPH reported that “more than 20,000 books based on the three Star Wars movies” were sold in the past 10 years, making these books its “all-time science fiction bestsellers”.6

With sci-fi becoming a major part of the Singaporean literary diet, the Singapore Science Centre organised an English-language sci-fi short story competition in 1979. It hoped to develop “the writing skills of Singaporeans and at the same time promote the idea of science as part of culture”.7 The competition was co-organised with the Society of Singapore Writers and the Rotary Club of Jurong, and attracted 108 entries.8 During the prize presentation ceremony, then Minister of State for Education Tony Tan said that “science fiction is concerned with the future society and its problems, and can be regarded as a ‘history of the future’”.9

The Singapore Youth Science Fortnight, first organised in 1978, also sought to encourage the study of science through events such as a Science Fiction Writing Competition, a Science Olympiad and a Science Fiction Film festival.10 In the same year, Brian Aldiss, the acclaimed British sci-fi writer was invited to give a public lecture on “The Future of the Book” and met local writers during a public forum on “The Writer and His Times”.11 He also wrote the foreword to Singapore Science Fiction, an anthology of the winning entries from the 1979 sci-fi short story competition.12

The winning entries included dystopian futures, issues of morality and philosophical musings on what constitute humanity. “Grape Shot”, for instance, is about a computer technician who finds out that his computer is surreptitiously storing and hiding the names of military people.13 The winning entry by Irene Pates titled “Who” tells the unlikely tale of a political leader whose head is transplanted onto the body of a garbage collector and the personality conflict that ensues. Coincidentally, in the same year, Pates’ work of fiction almost turned into a reality with newspaper headlines of heart transplant pioneer, Dr Christian Barnard, rejecting an alleged offer for a head transplant.14

Noted Singaporean poet and literary critic Kirpal Singh was a vocal champion for increased academic interest in the genre. His publication, Wonder and Awe: The World of Science Fiction, made inroads into local critical writing on sci-fi when it was published in 1980. He argued that “science fiction ought to be received and read as literature” by literary critics.15 In 1982, he urged the authorities to introduce science fiction into the school curriculum, because “through the reading of science fiction, people can have an imaginative and emotional grasp of the kind of things that the world of tomorrow will usher in”.16

Singaporean Sci-Fi Works

Short Stories

Aside from writing competitions, there were also local writers who published sci-fi works, often in the form of short story anthologies. One such writer was Gopal Baratham, known for his novels Sayang (1991) and A Candle Or The Sun (1991).17 His keen insights into human nature, a hallmark of his novels, also feature in his sci-fi short stories, “The Experiment” and “Ultimate Commodity”. The former, published in Figments of Experience (1981), reexamines the sci-fi trope of “man as the outcome of an experiment by superior beings”.18 “Ultimate Commodity” is a conspiratorial tale of a foreign substance that is released into the city’s water supply without public knowledge. As a result, everyone’s organs are revitalised to a “uniformly high standard”, becoming the ultimate commodity for organ transplants.19

Described as a “tireless spinner of tales”, Lim Thean Soo, author of five novels and over 100 short stories, explored human conflict and adversity in his sci-fi short stories “The Day of a Thousand Hours” (1981), “A Question of Identity” (1990), “Programmed Requital” (1990) and “Reversion” (1990).20 In “The Day of a Thousand Hours”, Lim creates a nearapocalyptic vision of the world and the rebuilding of civilisation, where it might have been fate for the “human beings to have face the unknown, struggle for survival with unshattered faith in their own continuance”.21 In Eleven Bizarre Tales published in 1990, Lim questions the transformative effects of human cloning, robotics and genetic engineering.

Terence Chua, a charter member of the Science Fiction Association (Singapore), published a collection of short stories in his anthology The Nightmare Factory (1991).22 The cover was conceptualised by Chua, who was aiming for a “dirty and grimy yet futuristic” look, one that “echoes a scene in one of the stories” in “which a cyborg commits suicide and his inner components scatter all over the floor”.23

Novels

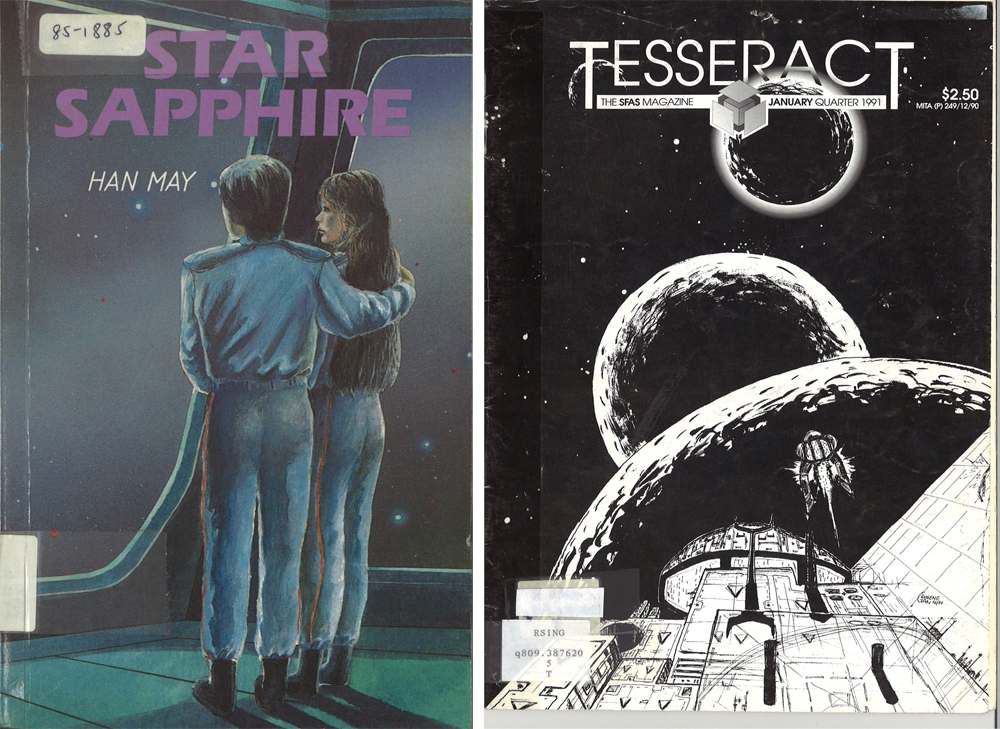

First published in 1985, Star Sapphire is arguably the first Singaporean sci-fi novel. Written by Joan Hon, under the pen name Han May, the book was highly commended in the “Fiction in English” category of the National Book Development Council Book Awards in 1986. The idea for the novel first came to Hon in 1982, and it took her eight months to complete the first draft.24 Taking the form of a bildungsroman, the novel is about the adventures of a young Asiatic scientist, Yva Yolan, who joins the massive intergalactic spacecraft Star Sapphire.

Another locally published sci-fi novel is 2084 (1996) by Raju Chellam. Chellam’s career in the info-technology industry may have given shape to this sci-fi satire. The action – which spans across a two-week period and set in Singapore – details a political crisis, and ideas such as space colonisation, inter-planetary mining and a water-based economy that threatens to cripple a country.25

The Science Fiction Association

The growing interest in sci-fi led to the establishment of the Science Fiction Association (Singapore) (SFAS) in 1989. The association was set up by a group of local die-hard science fiction addicts for the purpose of increasing “public’s awareness of sci-fi and fantasy as a legitimate genre of literature and art”.

The SFAS published a quarterly magazine called Tesseract, with the inaugural issue launched in January 1990. A total of 10 issues of the illustrated, black-and-white magazine were produced over a three-year period until the end of 1992.26 Tesseract was described by the editor, Glen Low, as “a balance of science fiction stories from contributors, features on sci-fi films and books that hit the international market, and illustrations”.27 Its newsletter, The Event Horizon, included an editor’s note, information on SFAS gatherings, and bite-sized information on sci-fi news and reviews.28

(Left) Star Sapphire is arguably the first Singaporean sci-fi novel. It was highly commended in the “Fiction in English” category of the National Book Development Council Book Awards in 1986. Pictured here is the cover of the first edition published in 1985. All rights reserved, Han, M. (1985). Star Sapphire. Singapore: Times Books International. Available via PublicationSG.

(Left) Star Sapphire is arguably the first Singaporean sci-fi novel. It was highly commended in the “Fiction in English” category of the National Book Development Council Book Awards in 1986. Pictured here is the cover of the first edition published in 1985. All rights reserved, Han, M. (1985). Star Sapphire. Singapore: Times Books International. Available via PublicationSG.(Right) Cover of the January 1991 (1st quarter) issue of Tesseract. A total of 10 issues were produced over a three-year period until the end of 1992. All rights reserved, Science Fiction Association (Singapore). (1990). Tesseract. Singapore: SFAS. (Call no.: R q809.3876205 T).

The launch of the association in 1990 was graced by the aforementioned Aldiss. In an interview Aldiss said:

“Singapore is a natural place for science fiction. Science fiction is an extrapolation of present-day trends – it also serves as a critique of society. It offers new visions, new ways of looking at things. Especially in a highly technological society like Singapore, it has a major role to play in the education of the imagination.”29

The association also organised an art competition for sci-fi and fantasy works, titled “Windows of the Mind”, to coincide with the Singapore Festival of Arts held that year. The first prize went to local author and illustrator, Joash Moo.30

By the 2000s, there were more platforms and opportunities for writers – both novice and established authors − to experiment with sci-fi and for fans to get together. As Singapore moves towards the vision of a “smart nation”, perhaps sci-fi does have a “natural place” in the city-state.

SCI-FI ON SCREEN AND STAGE

English

Stella Kon’s first sci-fi story was “Mushroom Harvest”, written when she was still in school. It was first published in Monsoon, a periodical on Singapore literature, in 1962 and reprinted in 22 Malaysian Stories in 1968.31 Kon had “always read and enjoyed science fiction” and subsequently penned two sci-fi plays: “Z is for Zygote” and “To Hatch a Swan”.32 The former is based on the premise that people are only entitled to conceive children according to a point system, while the latter explores the subject of surrogacy. Both plays were first staged in Ipoh in 1971 as a double bill under the title, A Breeding Pair.33

Stella Kon’s sci-fi plays, “Z is for Zygote” and “To Hatch a Swan”, were published in a book titled A Breeding Pair in 2000. Written during the 1970s, the plays deal with concepts that were considered futuristic at the time of writing, such as surrogate motherhood and fertility control. All rights reserved Kon, S. (2000). A Breeding Pair. Singapore: Raffles, an imprint of SNP Editions Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING S822 KON).

Stella Kon’s sci-fi plays, “Z is for Zygote” and “To Hatch a Swan”, were published in a book titled A Breeding Pair in 2000. Written during the 1970s, the plays deal with concepts that were considered futuristic at the time of writing, such as surrogate motherhood and fertility control. All rights reserved Kon, S. (2000). A Breeding Pair. Singapore: Raffles, an imprint of SNP Editions Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING S822 KON).

The first home-grown sci-fi feature film, Avatar, was directed by Kuo Jian Hong and staged in 2004.34 It was released in the US in the same year as Cyber Wars.35 The cast included local actors such as Lim Kay Siu and Kumar as well as internationally acclaimed actress Joan Chen. Shot on location in Singapore, the film is set in Sintawan, a futuristic Asian city-state where “lives are controlled by a system known as Cyberlink”.36

Chinese

Journalists from the Chinese newspaper, Lianhe Zaobao, staged four Chinese plays in July 1985 as part of its A Night of Comedies performance held at the Victoria Theatre. Two of the plays – Hopeful for the Son and Happy Forever – were adapted from Taiwanese futurist science fiction stories. The former puts the spotlight on modern birth control and paid surrogacy, while the latter tells of one man’s search for happiness on moon.37 Sci-fi also hit the small screen in the 1980s when the former Singapore Broadcasting Corporation produced the first Mandarin science fiction serial, Man From The Past, in 1985, and the 1988 sci-fi romantic comedy series Star Maiden.38

Malay

In 1986, local comedian Ahmad Nawi scripted his first play titled Para Benon. The 45-minute drama, which was staged on 15 October as part of Sriwana’s annual show, Malam Puspasari, is set in a post-apocalyptic world and centres on a group of nuclear holocaust survivors attempting to rebuild civilisation in the 23rd century. In an interview, Ahmad shared that “this is the first time that an attempt has been made to stage a science fiction drama, albeit a comedy [in Malay].” The cast was dressed in specially designed “space-age costumes”.39

Tamil

In 1966, the first Tamil science fiction play with a local setting was written and directed by theatre pioneer, S. S. Sarma. Titled Vinveli Veeran (The Man from Outer Space), the set design and costume included “dancing amidst the clouds in space, a robot man and a Science Lab”.40 It was lauded as a pioneering effort to explore different genres within the Tamil theatre scene. The play details the story of a local professor who seeks to explore outer space and highlights two themes: science and the concept of a higher being.41

Nadia Arianna Ramli is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s arts collections, with a special focus on literary and visual arts. Her research interests include Singapore literature and theatre studies.

Nadia Arianna Ramli is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s arts collections, with a special focus on literary and visual arts. Her research interests include Singapore literature and theatre studies.

REFERENCES

Bould, M., et. al. (Eds). (2009). The Routledge companion to science fiction. London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: R 809.38762 ROU)

Hartwell, D.G. (1996). Age of wonder: Exploring the world of science fiction. New York: Tor. (Call no.: R 809.38762 HAR)

NOTES

-

Lundberg, J.E. (Ed.). (2013–). LONTAR: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction. Singapore: Math Paper Press (2013–), Epigram Books (2016–). (Call no.: RSING 828.995903 LJSASF); Chng, J., & Yang, J. (Eds.). (2012). The ayam curtain. Singapore: Math Paper Press. (Call no.: RSING S823 AYA); Lim, R., & Maisarah Abu Samah. (Eds.). (2012). The steampowered globe. Singapore: ASiFF. (Call no.: RSING S823 STE) ↩

-

Naz Achnas. (1953). Tungga dan piring terbang. Singapore: MIBS. Available via PublicationSG; Van Der Putten, J., & Barnard, T.P. (2007). Old Malay heroes never die. In I. Gordon, M. Jankovich & M. P. McAllister (Eds.), Film and comic books (pp. 249, 293). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. (Call no: RART 791.43657 FIL) ↩

-

Yap, C. (1982, December 21). Enter Pluto-Man. The Straits Times, p. 1; Chandran, K. (1987, December 12). The amazing adventures of Captain V. The Straits Times p. 1; Tan, H.Y. (1995, July 15). What’s so funny? The Straits Times, p. 38; New guys in toon town. (1991, December 29). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewpsaperSG; Wong, R. (1983). The valiant Pluto-Man of Singapore. Singapore: Fantasy Comics; Captain V Productions. (1988) The amazing adventures of Captain V. Singapore: Captain V Productions. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Yue, R. (1978, January 15). Year of the great sci-fi film revival. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

More turn to reading science fiction novels. (1978, June 25). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chia, H. (1988, April 16). Fantastic journey. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Inspiring our aspiring writers with sci-fi. (1979, May 6). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Silva, G. (1979, August 2). Our budding sci-fi writers. New Nation, pp. 10-11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sci-fi a field for our writers: Minister. (1979, August 2). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Holmberg, J. (1978, August 31). A fortnight of science. New Nation, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG;Ministry of Culture. (1980, May 23). Speech by Dr. Tony Tan Keng Yam, Senior Minister of State for Education, at the opening ceremony of the Singapore Youth Science Fortnight at the Raffles Institution on 23rd May 1980. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Singh, K. (1980, August 3). The sci-fi novelist who never forgot army days in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Souza, J. (1980, October 30). S’pore can go space setting, says Aldiss. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mad dash at last minute to send story. (1980, October 29). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Silva, G. (1979, August 2). Top sci-fi writer imagined it all. New Nation, p. 6; Jordan, H. (1979, December 7). Head transplant research raises disturbing questions. The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singh, K. (1980). Wonder and awe: The world of science fiction. Singapore: Chopmen-Publishers. (Call no.: RSING S824 KIR) ↩

-

Lecturer calls for sci-fi to be school subject. (1982, March 7). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Koh, B.S. (1991, July 13). Neurosurgeon wins literary award. The Straits Times, p. 26; Koh B.S. (1995, March 4). Issues of trust and betrayal. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Geer, P. (1980, November 8). Promise of a future in our sci-fi writing. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Baratham, G. (1981). The experiment. In Figments of experience (p. 29). Singapore: Times Book International. (Call no.: RSING S823 GOP) ↩

-

Baratham, G. (1981). Ultimate commodity. In Figments of experience (pp. 103–110). Singapore: Times Book International. (Call no.: RSING S823 GOP) ↩

-

Koh, B.S. (1991, March 2). Tireless tale spinner. The Straits Times¸ p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG, Lim, T.S. (1981). The parting gift and other stories (pp. 128–132). Singapore: Sri Kesava. (Call no.: RSING S823.01 LIM); Lim, T.S. (1990). Eleven bizarre tales. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING S823 LIM) ↩

-

Chua, T. (1991). The nightmare factory: Stories from the edge. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING S823 CHU) ↩

-

Cover story. (1991, August 31). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, C.C. (1986, September 13). ‘Star-struck’ writer comes out of the closet. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Han, M. (1985). Star sapphire. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING S823 HAN) ↩

-

Chellam, R. (1996). 2084: A novel. Singapore: Asiawide Publications. (Call no.: RSING 828.995403 RAJ) ↩

-

Sci-fi fans to launch club. (1990, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Science Fiction Association (Singapore). (n.d.) Tesseract. Retrieved from Science Fiction Association (Singapore) website. ↩

-

Loh, T.L. (1989, November 27). Practical aims of fantasy buffs. The New Paper, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Science Fiction Association (Singapore). (1992, November). The Event Horizon: Newsletter of the Science Fiction Association of Singapore. Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING 809.38762 EH); Science Fiction Association (Singapore), Jan 1993; Science Fiction Association (Singapore), Oct 1994. ↩

-

Lee, M. (1990, October 30). Sci-fi fanatics. The New Paper, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 17 Oct 1990, p. 25; Aldiss, B. (1991). Tesseract, Jan Qrt, 8–9. [Brian Aldiss unbound]. (Call no.: RSING q809.3876205 T) ↩

-

Koh, B.S. (1990, October 20). Surface treatment. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kon, S. (2000). A breeding pair. (p. 1). Singapore: Raffles an imprint of SNP Editions Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING S822 KON); Fernando, L. (1968). Mushroom harvest (pp. 206–215). In Twenty-two Malaysian stories. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia). (Call no.: RCLOS 828.99 FER); Lim, S.W. (ed.). (1961). Monsoon, 1(2), pp 15–23. Singapore: G.H. Kiat & Co. (Call no.: RCLOS 052 MON) ↩

-

Stella Kon Pte Ltd. (n.d.). Stella Kon: Plays. Retrieved from Emily of Emerald Hill website; Kon, 2000, p. 2. ↩

-

Loh, S. (2004, August 26). S’pore film reaches out to the world. The Straits Times, p. 66. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, K.Y. (2009, October 27). ‘Art comes from dissent’. The New Paper, pp 2–3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 26 Aug 2004, p. 66; Yong, S.C. (2005, March 4). Avatar. Today, p. 42. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, A.Y. (1985, June 25). Newspaper to stage drama performances next month. Singapore Monitor, p. 18; Goh, B.C. (1985, July 3). Dramatists play it for laughs. The Straits Times, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, S.Y. (1984, December 9). A first attempt at adult comedy. Singapore Monitor, p. 12; Tan, J. (1984, December 2). Cameras to roll for SBC’s first sci-fi production. The Straits Times, p. 4; Wee, T.L. (1988, March 14). Criticism of SBC unfair. The Straits Times, p. 22; Star Maiden cast draws the crowds despite rain. (1988, February 21). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Haron A. Rahman. (1986, October 13). A show to entertain and to introduce new faces. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Varathan, S., & S. Hamid. (2008). Ciṅkappūr Tamil̲ nāṭaka varalār̲u 1935–2007= Development of Tamil drama in Singapore from 1935–2007. Ciṅkappūr: Ciṅkappūr Intiyak Kalaiñar Caṅkam. (Call no.: Tamil RSING 792.095957 VAR) ↩

-

50 Faces. (2014, August 23). SSS3 of 5 Breaking New Ground [Video recording]. Retrieved from 50 Faces website. ↩