Swan & Maclaren: Pioneers of Modernist Architecture

Singapore’s oldest architectural firm may be better known for designing the Raffles Hotel but it’s their 1930s Modernist buildings that are truly revolutionary. Julian Davison has the details.

The Sime Darby godown photographed in 1974. With its curved end elevation, C.J. Stephen’s godown was a distant echo of Harry Robinson’s St Andrew’s Mission Hospital in 1922. Photograph by Marjorie Doggett, Characters of Light, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Sime Darby godown photographed in 1974. With its curved end elevation, C.J. Stephen’s godown was a distant echo of Harry Robinson’s St Andrew’s Mission Hospital in 1922. Photograph by Marjorie Doggett, Characters of Light, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Swan & Maclaren, the oldest architectural practice in Singapore, is a name that is synonymous with many of the city’s heritage buildings. Raffles Hotel, Goodwood Park, the Victoria Memorial Hall and Theatre, Chased-El Synagogue and Tanjong Pagar Railway Station are just some of the instantly recognisable architectural landmarks designed by the firm whose origins date back more than a century.

It was in 1887 when Archibald Swan and Alfred Lermit started Swan & Lermit, a civil engineering company, in the British colony. Lermit left in 1890, and Swan continued on his own for a while before forming a new partnership with fellow Scotsman J.W.B. Maclaren in 1892 under the name Swan & Maclaren. Successful from the outset, it became the island’s pre-eminent architectural practice when Regent Alfred John Bidwell, a professionally trained architect, joined the firm three years later, winning several prestigious commissions in rapid succession.

But it wasn’t always porticoes, pediments and Corinthian columns with Swan & Maclaren, at least not in the years leading up to World War II and in the immediate post-war period. Moving away from the Classical Renaissance style favoured by Bidwell (who had left the firm in 1911), Swan & Maclaren became agents of change, radical revolutionaries who embraced the Modernist movement with passion. Working with reinforced concrete, the newest breakthrough in building material, the firm introduced a new style of architecture in 1920s Singapore.

A New Chapter in Local Architecture

As we pause to reflect on the past architectural glories of Swan & Maclaren in 2017 – as the firm commemorates its 125th year of its founding in Singapore – it is also timely to look at the less celebrated, less well known aspect of the Swan & Maclaren story: its place in Singapore’s history as pioneers of the Modernist architectural movement (see text box below).

Modernism, as an architectural movement, was a long time coming to Britain and did not properly take off in the country until around 1930. This was a very different situation compared with Continental Europe where World War I acted as a positive stimulus to the advance of Modernism.

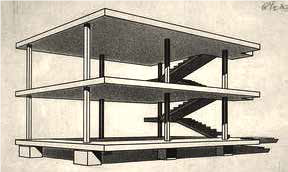

In Amsterdam, for example, we see the manifestation of Modernism in the founding of the Dutch artistic movement De Stijl in 1917, followed by the Bauhaus school of art in Weimar Germany in 1919. In France, witnessing the devastation of Flanders in 1914 would lead Le Corbusier, who would become one of the leading proponents of Modernist architecture, to come up with his concept of the Maison Dom-ino (see photo in text box). This was an open-plan design comprising precast concrete floor slabs supported by thin concrete columns with a stairway located at one of end to provide access from one floor to another. Initially intended as a quick-fix solution to provide mass housing for people displaced by the war, the Dom-ino concept became one of the essential building blocks of Modernist architecture.

In England, however, the post-World War I mood was more conservative, with most public architecture in the years immediately following the war reverting to some form of prewar Classicism – either an update of Edwardian Baroque or else neo-Georgian revivalism. Art Deco didn’t really catch on in the country until the late 1920s and only then in a relatively minor and circumspect way, being employed mainly for cinemas, hotels and ritzy department stores, while Modernism didn’t get a look-in at all. If Continental Europe’s reaction to the carnage of World War I was to start anew, a kind of tabula rasa mentality or “starting from zero” as Walter Gropius famously put it,1 in Britain it was the exact opposite, a desire to embrace the certainties and comforts of an idealised, romanticised past.

Here in Singapore, much the same situation prevailed. The architecture of the post-World War I era witnessed a major rebuilding of downtown Singapore, with the erection of a dozen or more brand new office blocks, corporate headquarters and bank buildings in and around Raffles Place and along Collyer Quay. At the same time, the government invested heavily in the construction of new public buildings: the Singapore General Hospital and College of Medicine Building in 1926; the Fullerton Building (which housed the General Post Office, today the Fullerton Hotel) in 1928; the Municipal Building (later renamed City Hall and now repurposed as the National Gallery) in 1929; and a new home for the office of the Chinese Protectorate (today’s Family Justice Courts) in 1931.

In the 10 years following the end of World War I in Europe, the urban landscape of Singapore was radically transformed, forging an architectural identity for the city that was in step with other major global financial centres of the time – these were buildings that would not have looked out of place in London, Manhattan or Shanghai. The point to make here, however, is that each and every one of these new constructions came with a Classical pedigree. Anyone looking at these new, post-World War I edifices would have been immediately aware that they were contemporary buildings by virtue of their size, scale and relative proportions. This was clearly not a case of Victorian revivalism in which architects tried to recreate the architecture of the past, but rather a new kind of Classicism for the 20th century.

These were monumental buildings whose proportions owed nothing to Vitruvius2 and everything to modern building materials and construction techniques – reinforced concrete, steel frames, plate glass and artificial stone. They were characterised by a massive base and gigantic colonnades, whose columns rose through two or more storeys, with an equally outsized cornice and parapet to match. The Municipal Building, for example, has all of these qualities in spades and at the time of its completion in 1929, was precisely what people thought a modern civic building should look like.

This preference for Classically influenced buildings was largely because the general public was not very receptive to the “new architecture” of the early Modernists – it was just too different to the untrained eye. “Modern German dwelling houses look like the products of a cubist or futurist nightmare”, declared the editor of The Straits Times in June 1929.3 “Although they are obviously designed to act as sun-traps, there is no architectural merit in the utilitarian purpose. They are odd, uncouth, apparently unfinished. The average child can construct something aesthetically more pleasing with a Meccano set”.4

An Early Brush with Modernism

All this makes Singapore’s first Modernist building all the more surprising – a hospital for the St Andrew’s Medical Mission at Erskine Hill, which dates from 1922, no less. Even more extraordinary, perhaps, is the fact that it was designed by Swan & Maclaren’s Harry Robinson, a surveyor by training and someone who was better known as Singapore’s leading land assessor than for his avant-garde architecture.

St Andrew’s Medical Mission was founded in Singapore in 1913 with the opening of a dispensary on Bencoolen Street by Dr Charlotte E. Ferguson Davie, wife of the Right Reverend Charles Ferguson Davie, Bishop of Singapore. Other dispensaries followed, with an eight-bed ward for more serious cases attached to the Chinatown dispensary in 1915 (the latter was subsequently relocated to River Valley Road). A training programme for nurses and midwives was established the following year and, by 1918, the mission was able to consider a more ambitious undertaking, namely a purpose-built hospital.

A plot of land on the slopes of Mount Erskine was obtained from the colonial government on very favourable terms in 1921; the site was ideal because it was close to the heart of Chinatown, where many of the mission’s poorest patients lived. The foundation stone, which was laid by Mrs Lee Choon Guan, in October the following year, was inscribed with the words: “To the Glory of God and for the relief of the suffering.”5

The plans drawn up by Robinson in 1922 were for a building of astonishing modernity, given the date and the fact that this was Singapore and not Continental Europe. That St Andrew’s Mission Hospital was exactly contemporaneous with the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank and Union buildings along Collyer Quay only underlined the originality of its design. While the latter two edifices were decked out in the full pomp and circumstance of Swan & Maclaren’s postwar corporate Baroque style, complete with rusticated basements, Ionic colonnades and swags, there were no such fripperies in Robinson’s plan for the hospital. This was a stark, uncompromising essay in Modern architecture that answered perfectly to Le Corbusier’s Purist ethic. Perhaps it was simply a case of economics – there just wasn’t the money to spend on superfluous adornment – but even by the European standards of the day, Robinson’s hospital looked pretty cutting edge.

St Andrew’s Mission Hospital at Erskine Hill, photographed in 1938. Designed in 1922 by Harry Robinson of Swan & Maclaren, the three-storey concrete frame building provided ccommodation for 50 in-patients with additional quarters for the European and Asian staff on the top floor. The flat roof afforded recreational space for both staff and patients. Courtesy of St Andrew’s Mission Hospital.

St Andrew’s Mission Hospital at Erskine Hill, photographed in 1938. Designed in 1922 by Harry Robinson of Swan & Maclaren, the three-storey concrete frame building provided ccommodation for 50 in-patients with additional quarters for the European and Asian staff on the top floor. The flat roof afforded recreational space for both staff and patients. Courtesy of St Andrew’s Mission Hospital.The hospital was well received in the press, though one suspects that the severity of the architecture startled some. The correspondent of the Singapore Free Press, for instance, thought the building “gaunt”, but recognised that:

“The completed structure has for its hallmark the severity of the science of healing. It might not, perhaps, be called from an architectural point of view a thing of beauty, but if we accept Ruskin’s view that beauty and usefulness should always be combined, then we can say that the building which stands boldly out in… unbeautiful surroundings, will make a record on its own merits.”6

St Andrew’s Mission Hospital was a landmark building for both Swan & Maclaren and the history of Singapore architecture – arguably the first Modernist building on record. That said, it would take almost 10 years before Robinson’s successors at Swan & Maclaren would return to a full-fledged Modernist agenda.

A Brief Diversion… then Modernism Takes Off

In the intervening years, Swan & Maclaren’s architects experimented with a range of styles. There were more buildings in the Modern Classical vein, notably the Chinese High School on Bukit Timah Road (1923); a bit of Neo-Georgian – Meyer Chambers in Raffles Place (1929); and even some forays into Art Deco, most famously Tanjong Pagar Railway Station (1929), and also the Malayan Motors showroom on Orchard Road (1925), with its starburst façade reminiscent of Eliel Saarinen’s Helsinki railway station, and the Majestic Theatre on Eu Tong Sen Street (1926).

Swan & Maclaren partners, Denis Santry and Frank Brewer, also experimented with the so-called Chinese Renaissance style – the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church (1924) and new premises for Anglo Chinese School (1924) in Cairnhill respectively, while Frank Lundon, the other senior partner at the firm, dabbled in a bit of this and that. Modernism, however, did not surface on the Swan & Maclaren agenda again until 1932, a full 10 years after Harry Robinson’s groundbreaking St Andrew’s Mission Hospital.

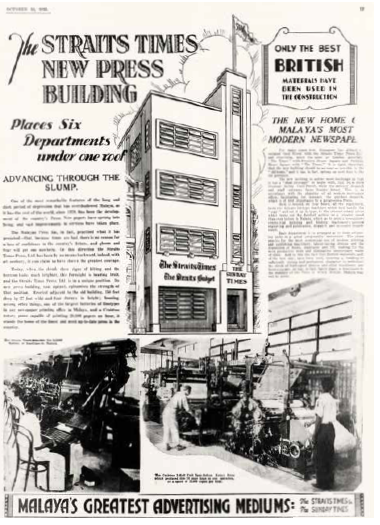

The building that truly kicked off Swan & Maclaren’s return to Modernism were the new premises for the Straits Times Press on Cecil Street in 1932, the plans drawn up by Doucham Slobodov Petrovitch, best known for designing the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station. Here he abandoned his Nordic Deco style for an out-and-out Modernist building in the Bauhaus tradition. This meant austere, unadorned façades with a lot of metalframed windows arranged in horizontal bands − very much the new aesthetic of the Modern movement.

A complete and detailed description of the building was provided in The Straits Times of 10 October 1933, the newspaper evidently very proud of its new premises: Within this house of steel, the floors… are of reinforced concrete, resting above the steel beams, and each slab is designed to carry machinery at any point. They are finished in hard white cement-granolithic giving a permanent and hard wearing surface. Wide staircases are also in reinforced concrete, similarly finished.7

The building also took into consideration the tropical climate and was designed to be naturally cool, “since Crittall’s steel windows provide the maximum amount of light and air”. More generally it had “an air of severe efficiency”. “All ornament and mouldings were omitted”, The Straits Times informed its readers, adding that “it is after all, a building specially adapted for pounding printing presses where utility and strength are the two main essentials”.

Gleaming white throughout its interiors, the building had a viridian hue on the outside due to the use of green Albertone cement, a kind of granolithic “Shanghai” plaster. Pleasing in every respect and Singapore’s most modern building to date, the Straits Times Press premises were “a monument to the stability of the Press of which British Malaya may be proud”, the newspaper reported.

The Straits Times announcing the completion of its new building on Cecil Street in 1933. Designed by Doucham Petrovitch, it marked Swan & Maclaren’s return to Modernism after its first foray with the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital a decade earlier. The Straits Times, 10 October 1933, p. 17.

The Straits Times announcing the completion of its new building on Cecil Street in 1933. Designed by Doucham Petrovitch, it marked Swan & Maclaren’s return to Modernism after its first foray with the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital a decade earlier. The Straits Times, 10 October 1933, p. 17.Petrovitch followed up the Straits Times building with two more Modernist office blocks in the Central Business District in 1935. They were the Nunes Building at Malacca Street, and the Medeiros Building at Cecil Street. Both were commissioned by Swan & Maclaren’s long-time client, the Portuguese Mission who, in its early days, had wisely bought up much valuable real estate near the town centre. Completed in 1937, both buildings received considerable attention in the press, with The Straits Times devoting a four-page supplement to them in October that year: “Modern Continental cubist design… seen at its best”, praised the writer.8

For the Nunes Building, The Straits Times noted that:

“Reinforced concrete is the material used – very little wood has been employed in the construction, reducing to the minimum the risk of fire and ensuring cleanliness with the minimum of labour. The office accommodation is large and airy, admitting the maximum light, but through the use of special glass the dangerous rays and heat of the sun are effectively held at bay.”9

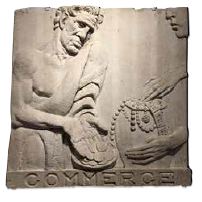

The facades of both buildings were characterised by a strong horizontal element, achieved by bands of metal-framed windows shaded by a continuous reinforced concrete canopy – this was what every Modernist architect aspired to – but in this instance, the severity of the facade was relieved somewhat by a series of decorative panels beneath the windows over the main entrance to each building. Designed by Cavalieri Rudolfo Nolli, Singapore’s resident Italian sculptor, the ornate panels symbolised various aspects of the modern Singaporean economy: commerce, agriculture, shipping, construction and the other industries.

The Nunes Building (left) and the Medeiros Building (right), photographed by the late Lee Kip Lin in 1982 and 1984 respectively. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore, 2009.

The Nunes Building (left) and the Medeiros Building (right), photographed by the late Lee Kip Lin in 1982 and 1984 respectively. From the Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore, 2009.Nolli was also responsible for the external finishes to the buildings, which were finished with “bush hammered granolithic facing and white cement from the yard of Cav. R. Nolli”. “The increasing popularity of bush hammered granolithic facings for buildings in Singapore”, The Straits Times noted, “is an indication of the extreme durability of this material under tropical conditions”, adding that “the material has the advantage of not discolouring as it is composed of natural colours – local granite and white cement”.10

Surviving decorative panel by Cavalieri Rudolfo Nolli from the Nunes Building. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

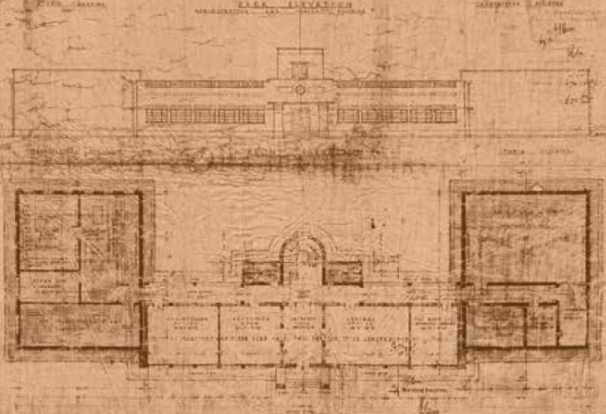

Surviving decorative panel by Cavalieri Rudolfo Nolli from the Nunes Building. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.At the same time Petrovitch was designing the J.A. Elias Building – nicknamed the Amber Building because of the amber-coloured marble used on the floor and walls of the entrance lobby – he was also working on one of his most significant commissions in Singapore, the studio complex for the newly constituted British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation on Caldecott Hill. This was his most austere work to date – a long, low building, just a single storey in elevation save for a central stair tower, which stuck up at the rear, providing access to an extensive roof terrace.

The central core of the building housed offices, reception rooms and a records library, to which was attached a windowless, bunker-like wing at either end. One wing was dedicated to the mechanics of broadcasting – transmitter room, machine room, air-conditioning plant and workshop – while the other was devoted entirely to studio space. This was a fairly uncompromising expression of the Modernist edict that form should follow function, a Brutalist composition avant la lettre, the most attractive feature being the roof-top terrace, which given the hilltop location offered panoramic vistas across the surrounding countryside, including “one of the most beautiful views on the island of Singapore, overlooking the woodfringed [MacRitchie] reservoir”.11

But it wasn’t all corporate and commercial stuff. Petrovitch was equally adept at turning out bijou Modernist villas when required, like the house he designed for the French construction company and property developer, Credit Foncier D’Extreme Orient, at Holland Park in 1934. With its flat roofs, cantilevered canopies, ship’s railings and horizontal bands of steel-framed fenestration, this was just about as radical a departure from the typical 1930s Singaporean bungalow as one could imagine. It might not have looked very pretty, but there was no doubting its Modernist credentials.

The Work of Frank Lundon

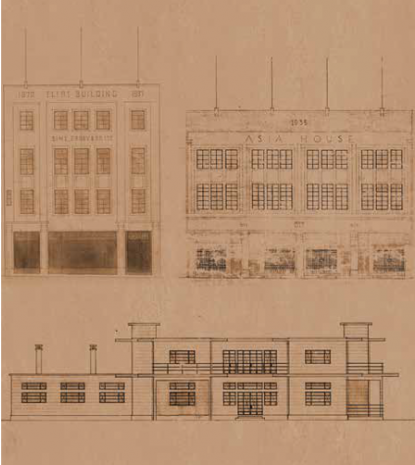

Nor was Petrovitch the only Swan & Maclaren architect to turn to Modernism in the 1930s. Even before Petrovitch had started working on his two office blocks for the Portuguese Mission, senior partner Frank Lundon was on a very similar trajectory when he was asked to design new office premises for the Asia Insurance Company at Robinson Road. Lundon’s Asia House was completed in September 1936.

Lundon was also responsible for a number Modernist bungalows and villas of the concrete box variety. It seems he was inspired by an extended tour he made of Britain, Germany and Holland while on leave in 1936, undertaken with the express intent of studying “the latest architectural developments” on the Continent. In an interview with The Straits Times on his return, Lundon said he “was most impressed by the quality of modern architectural design in Holland, particularly of houses and flats”.12 Clearly, Lundon was looking at the work of artists and architects closely associated with the De Stijl movement, such as J.J.P. Oud, Theo van Doesburg and Gerrit Rietveld, if the house he designed for Messrs Fogden Brisbane & Co. at Kheam Hock Road in 1936 is anything to go by.

Doucham Petrovitch’s architectural plan of the broadcasting station for the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation on Caldecott Hill, 1936. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Doucham Petrovitch’s architectural plan of the broadcasting station for the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation on Caldecott Hill, 1936. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. A composite image of architectural drawings from Swan & Maclaren showing the front elevations of (from clockwise): the J. A. Elias Building (1936) on Malacca Street by Doucham Petrovitch; Asia House (1935), the new premises for the Asia Insurance Company on Robinson Road, by Frank Lundon; and a private house in Holland Park (1934) for Messrs Credit Foncier D’Extreme Orient, by Doucham Petrovitch. The year indicated here refers to the time when all these buildings were commissioned. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A composite image of architectural drawings from Swan & Maclaren showing the front elevations of (from clockwise): the J. A. Elias Building (1936) on Malacca Street by Doucham Petrovitch; Asia House (1935), the new premises for the Asia Insurance Company on Robinson Road, by Frank Lundon; and a private house in Holland Park (1934) for Messrs Credit Foncier D’Extreme Orient, by Doucham Petrovitch. The year indicated here refers to the time when all these buildings were commissioned. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Work of C.J. Stephen and C.Y. Koh

And then there was C.J. Stephen, a somewhat shadowy figure since very little is known about his personal life and professional background compared with his Swan & Maclaren contemporaries, Lundon and Petrovitch. A partner since 1935, Stephen’s best known work prior to his Modernist phase was the Cold Storage flagship supermarket on Orchard Road, which evoked a kind of pared down Classicism that was only one step removed from ditching the whole Classical school of design altogether.

Three years later, Stephen came up with a new godown for Messrs Sime, Darby & Co. along Robertson Quay, which was about as Modern in sensibility as one could get. Likewise, a second godown for Messrs Guthrie and Co. was constructed the following year at North Boat Quay, on the site now occupied by Parliament House.

The last building on record for Stephen before the outbreak of World War II was a soft drinks manufactory and bottling plant at Mount Palmer for the Phoenix Aerated Water Works in 1939. The company was owned by the prominent Parsi businessman and philanthropist, Navroji Mistri (1885–1935) who had made his fortune in the fizzy drinks business – “There’s Joy in Every Glass” was the company slogan.

A composite image of architectural drawings from the Swan & Maclaren architect C.J. Stephen showing (from left): the front elevations of the godown for Messrs Sime, Darby &. Co. (1937) at Robertson Quay; and the Phoenix Aerated Water Works (1939) for N.R Mistri Esq. at Mount Palmer. The owner of the latter, Navroji Mistri was as generous as he was wealthy; the Mistri Wing of the General Hospital and Mistri Road were named after him. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A composite image of architectural drawings from the Swan & Maclaren architect C.J. Stephen showing (from left): the front elevations of the godown for Messrs Sime, Darby &. Co. (1937) at Robertson Quay; and the Phoenix Aerated Water Works (1939) for N.R Mistri Esq. at Mount Palmer. The owner of the latter, Navroji Mistri was as generous as he was wealthy; the Mistri Wing of the General Hospital and Mistri Road were named after him. Swan & Maclaren Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.This was another austere building in the Bauhaus tradition with more bands of metal-framed windows emphasising the horizontal aesthetic that was central to the Modernist movement. In this instance, the severity of the elevation was relieved by a tower reminiscent of contemporary industrial buildings on the Great West Road leading out of London – the so-called “Golden Mile” – famous for its eclectic mix of Art Deco and early Modernist architecture.

Last but not least is Koh Cheng Yam, better known as C.Y. Koh, Swan & Maclaren’s first local architectural assistant who later led the firm in the post-World War II era. Like Petrovitch, Koh had studied at the Architectural Association in London and was an Associate member (later Fellow) of the prestigious Royal Institute of British Architects.

On his return to Singapore in 1938, Koh joined Swan & Maclaren and in the final months before the outbreak of World War II in December 1941, he designed what is without doubt one of the finest pre-war buildings still extant in Singapore – a beautiful Modernist gem, greatly admired to this day – the Water Boat Office on Fullerton Road for Messrs. W. Hammer & Co. (Although the building wasn’t erected until after the war, it can be considered prewar on account of the fact that it had been designed before the war – the building went out to tender in June 1941.)

Hammer & Co. had been around since the turn of the 20th century, supplying ships in the harbour with fresh water. Its new flagship three-storey building comprised a lobby and reception area, offices, a lounge and dining room, stores, and a marvellous roof-top terrace with splendid views across the Inner Harbour and the sea beyond. Naturally, a strong nautical theme is evident in the external detailing of the structure, with portholes and railings and a lantern over the stairs leading up to the roof terrace, which from some angles resemble a ship’s bridge and from others like the conning tower of a submarine. The exterior was rendered in artificial stone – coloured an appropriate shade of battleship grey – with terrazzo floors and panelling for the main reception area. If Koh had never designed another building in his life, he would always be remembered for his Water Boat Office.

The Water Boat Office photographed in 1952. Although designed by C.Y. Koh in mid-1941, the war intervened and the Water Boat Office was not completed until 1948. Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

The Water Boat Office photographed in 1952. Although designed by C.Y. Koh in mid-1941, the war intervened and the Water Boat Office was not completed until 1948. Courtesy of National Heritage Board.Harry Robinson, Frank Lundon, Doucham Petrovitch, C.J. Stephen, and C.Y. Koh. Some of the names are still familiar to us, while the others have slipped over the horizon of history, but these were the men from Swan & Maclaren who collectively effected a quiet revolution in Singaporean architecture in the 1930s, notwithstanding the fact that only two buildings from that era are still around today – St Andrew’s Mission Hospital and the Water Boat Office.

Post-war, everything was different and Modernism hardly raised an eyebrow, but before World War II, Swan & Maclaren were style leaders, clearly at the forefront of the Modernist movement of architecture in Singapore and instrumental in preparing the way for the shape of things to come.

MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE

Modern architecture as a school of architecture (as opposed to a building that is merely contemporary), describes a new architectural style that emerged in many Western countries in the decade following World War I.

Modernist architecture was based on use of the latest construction technology and building materials – reinforced concrete, and steel and glass – applied according to the principles of a rational or functionalist theory of design, enshrined in the maxim “form follows function”. Central to the Modernist ethos was the rejection of historical precedent and an abhorrence of ornamentation – a “crime” according to Adolf Loos, an influential Czech architect from the late 19th century and a proponent of the Modernist architectural movement.13

Rigorously applied, these functionalist principles tended to result in a style of architecture that was typically rectangular in plan, sheer-sided, with sharp corners and a flat roof. In other words, it was rather box-like, which led to it sometimes being described as “Cubist” architecture, playing on a perceived resemblance to paintings by contemporary artists like Pablo Picasso and George Braques, who led the avant-garde art movement of the same name.

This new architectural approach was also known as the International Style,14 not least because wherever one encountered Modernist architecture, whether it was in Europe, the Americas, Italian East Africa or Tel Aviv in Israel, it all looked remarkably the same.

A drawing showing the structural skeleton of the Maison Dom-ino by Le Corbusier (1886-1965), France’s leading proponent of Modernist architecture. This open-plan design of precast concrete floor slabs supported by concrete columns with a stairway located at one of end to provide access from one floor to another became one of the essential building blocks of Modernist architecture. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A drawing showing the structural skeleton of the Maison Dom-ino by Le Corbusier (1886-1965), France’s leading proponent of Modernist architecture. This open-plan design of precast concrete floor slabs supported by concrete columns with a stairway located at one of end to provide access from one floor to another became one of the essential building blocks of Modernist architecture. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Supposedly freed from the spurious distractions of stylistic convention, Modernism was a new architecture for a new age. To what extent it fulfilled its lofty ambitions, academics will argue, is a moot point, but whichever way one sees it, there is no doubt that Modernism as an architectural practice was just about as far removed from the archetypal image of colonial architecture, with its Doric columns and pedimented porticoes, as one can get.

Anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow, Dr Julian Davison is currently writing a history of Singapore’s oldest architectural practice, Swan & Maclaren, whose origins go back to the late 1880s. The book is scheduled to be published in the last quarter of 2017.

Anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow, Dr Julian Davison is currently writing a history of Singapore’s oldest architectural practice, Swan & Maclaren, whose origins go back to the late 1880s. The book is scheduled to be published in the last quarter of 2017.

NOTES

-

Wolfe, T. (1983). From Bauhaus to our house. London: Abacus. (Call no.: RART 720.973 WOL) ↩

-

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio is the first century BC Roman architect, engineer and author whose multi-volume architectural treatise, De architectura, is the only contemporary work on Roman architecture that has survived from ancient times. ↩

-

The new architecture. (1929, June 10). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Meccano is the brand name of a model construction kit, comprising re-usable metal strips, plates, anglegirders, axels, wheels, gears and so forth, which can be connected together using washers, nuts and bolts. Invented in 1901, Meccano is still manufactured today in France and China, but probably reached the height of its popularity between the two world wars, when it provided an invaluable introduction to the principles of mechanics and engineering for boys. ↩

-

St. Andrew’s Hospital. (1923, May 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Mrs Lee was the wife of business tycoon and prominent Straits Chinese leader, Lee Choon Guan (1868–1924). ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 May 1923, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times new press building. (1933, October 10). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Portuguese Mission’s investment in new buildings (1937, October 5). The Straits Times supplement, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Modern continental design of new offices. (1937, October 5). The Straits Times supplement, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Materials used in constructing Nunes and Medeiros. (1937, October 5). The Straits Times supplement, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malayan B.B.C.’s building on hill off Thomson Road. (1936, May 31). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bought autogiro. (1936, October 3). The Straits Times, p.13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The phrase came from Adolf Loos’ essay, “Ornament and Crime”, written in 1908. ↩

-

The term International Style is derived from the title of a book by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, which was written to accompany the International Exhibition of Modern Architecture held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1932. The book identifies the various characteristic elements common to Modernist architecture around the world. See Hitchcock, H., & Johnson, P. (1996). The international style. New York: W. W. Norton. (Call no.: RART 724.6 HIT). The term had previously been used by Water Gropius, and in a similar context, in his 1925 publication Internationale Architektur. ↩