Nyonya Needlework and the Printed Page

Cheah Hwei-Fe’n examines the impact of print media on the time-honoured craft of Peranakan embroidery and beadwork.

Figure 1: A Peranakan wedding couple with a child attendant, early 20th century. Wedding celebrations often showcased nyonya needlework in the form of accessories for the wedding couple and their entourage, and soft furnishings in the nuptial chamber. Photograph by Che Lan & Co, Jogjakarta. Collection of the Peranakan Museum. Gift of Lee Kip Lee.

Figure 1: A Peranakan wedding couple with a child attendant, early 20th century. Wedding celebrations often showcased nyonya needlework in the form of accessories for the wedding couple and their entourage, and soft furnishings in the nuptial chamber. Photograph by Che Lan & Co, Jogjakarta. Collection of the Peranakan Museum. Gift of Lee Kip Lee.Singapore’s national respository of nyonya needlework, comprising the embroidery and beadwork of the Peranakan1 (or Straits Chinese) community from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Myanmar, is unsurpassed as a public collection. Enhanced in recent years through acquisitions and gifts, the quality of the objects and their diversity of styles show how imitation, innovation and cultural borrowing have all contributed to the art of nyonya needlework.2

Nyonya needlework has its roots in the aesthetics of Chinese embroidery, drawing on a well-established set of symbols to convey form and meaning. But embroiderers have also turned to other sources for novel patterns and inspiration. Some of the beadwork and embroidery on display at the Peranakan Museum in Singapore illustrate the connections between print and pattern in nyonya needlework, highlighting the role of the print media.

Pattern books, fashion magazines, journals, Chinese classical texts, and even children’s books have played a role in introducing new motifs as well as the translation of information into visual form.

Symbolism and Ornamentation

Nyonya needlework is characterised by exquisite workmanship, complex textures and fine motifs, often out of scale with each other. Patterns were often worked in silk floss and twisted silk yarns, iridescent peacock feathers, glass and metal beads, and gold and silver threads of different textures. The interplay of luxurious materials and kaleidoscopic colours have all conspired to create highly decorative, tactile and scintillating surfaces.

Whether they were stitched by Peranakan Chinese women in a domestic setting or by professional craftspeople, nyonya needlework embodied labour and expensive materials, communicating both wealth and fine taste. Their designs also incorporated the use of symbols, stories and customs. In the closely-knit circles of Peranakan Chinese society, family reputations were fiercely guarded and a person’s behaviour was closely scrutinised and often critiqued. In such an environment, symbolic and non-verbal cues were equally indicative of one’s upbringing, understanding of tradition and family background, and some of these aspects filtered into nyonya needlework designs.

The practice of embroidery in Peranakan Chinese culture goes back at least 300 years, although the oldest extant nyonya embroideries we know of date to the mid-19th century. Women’s footwear and purses were the most commonly embroidered items, but it was at wedding celebrations that nyonya needlework was at its most glorious, taking the form of soft furnishings in the nuptial chamber and accessories for the wedding couple and their entourage (see figure 1 above).

Befitting such occasions, nyonya needlework was typically decorated with auspicious images of flowers, animals and precious objects drawn from Chinese art and symbols. Chinese embroidered textiles provided the models for many designs. Imagery for needlework could also have been copied from furniture, silverwork and ceramics found in the homes of Peranakan Chinese families. These familiar motifs conveyed wishes for good fortune, longevity, a blissful marriage, successful progeny and good health.

Print media offered yet another exciting visual resource, opening up a new treasure trove of designs and facilitating the spread of new themes and ideas in nyonya needlework.

Embroidery and Printed Patterns

For centuries now, the printed page has offered prototypes for embroidery designs. Chinese books of embroidery patterns, typically from woodblocks, made it easier for embroiderers to reproduce conventional imagery in thread. However, few have managed to survive as these printed papers have degraded over time when designs were transferred onto fabric.3 Extant Qing dynasty (1644−1911) pattern books carried a range of archetypal designs, from individual motifs of birds and flowers that could be arranged by the embroiderer to more intricate and completed compositions for purses and shoes. These pattern books also included complex scenes featuring mythological figures, warriors and Taoist deities.

Since the 16th century, European artisans, including professional and amateur embroiderers, have adapted illustrations from printed herbals (treatises on plants as medicine and food) and bestiaries (descriptions of real and mythical animals) as well as engravings in bibles and almanacs.4 Pattern books for embroiderers were also published around this time, becoming an enduring source for contemporary sewing cultures.5 Later, embroidery patterns, influenced by current fashion trends and accompanied by stitching instructions, were published in European women’s magazines.

Historian Dagmar Schäfer argues that printed patterns and guide books can be understood as part of “an incipient knowledge codification process”.6 Their portable format enabled information to be transferred between merchants, craftsmen and customers as well as across “cultural and knowledge spheres.” It did not matter if the audience was illiterate because historical pattern books contained minimal text.7 Printed images – in books, magazines and newspapers, calendars, and even packaging paper – facilitated the dissemination and transmission of designs both within and across cultures.

The first instructional text on nyonya beadwork was published only as recently as 2009 by a Singaporean beader Bebe Seet.8 But the impact of the printed page can be found much earlier in nyonya needlework. Books and fashion magazines were imported into the Straits Settlements (comprising Penang, Melaka and Singapore) and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) in the 1800s, as were Berlin woolwork (see text box below) patterns where designs were marked out on point paper (similar to graph paper).

Initially sold through shops catering to Europeans, these woolwork patterns would have become more widely available over time and crossed the seas into this part of the world. The names handwritten inside some books indicate that the nyonyas had in their possession pattern books and stitch guides such as the 1920s Chinese Sun Sun Cross Stitch Book series and Thérèse de Dillmont’s Encyclopedia of Needlework.9 These publications would surely have had an impact on nyonya embroidery and beading. The following examples illustrate how print media enlarged the design world of nyonya needlework.

Cross-Cultural Peonies

In Chinese paintings and embroideries, the peony is usually depicted in full bloom with frilly- or wavy-edged petals. They can be depicted in the manner commonly seen in nyonya embroideries, or with more stylised smooth-edged petals.10 A third variation of the “peony”, especially in the gold embroideries of Java, is associated with designs found in European fashion journals, as in figure 2.

Figure 2: Tray cover or handkerchief with gold embroidery of floral stems at each corner, probably from Java, late 19th or early 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Figure 2: Tray cover or handkerchief with gold embroidery of floral stems at each corner, probably from Java, late 19th or early 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Figure 2 shows a handkerchief or tray cover embroidered with floral stems at each corner. The petals have scalloped edges and are arranged neatly around the core of the flower, much like the printed models in the Dutch magazine Gracieuse (see figure 3). This type of stylised “peony”, intertwined with the presentation of floral sprays in a bouquet (popularly known in batik terminology as buketan), continued to be applied to embroidery right into the 1930s.11

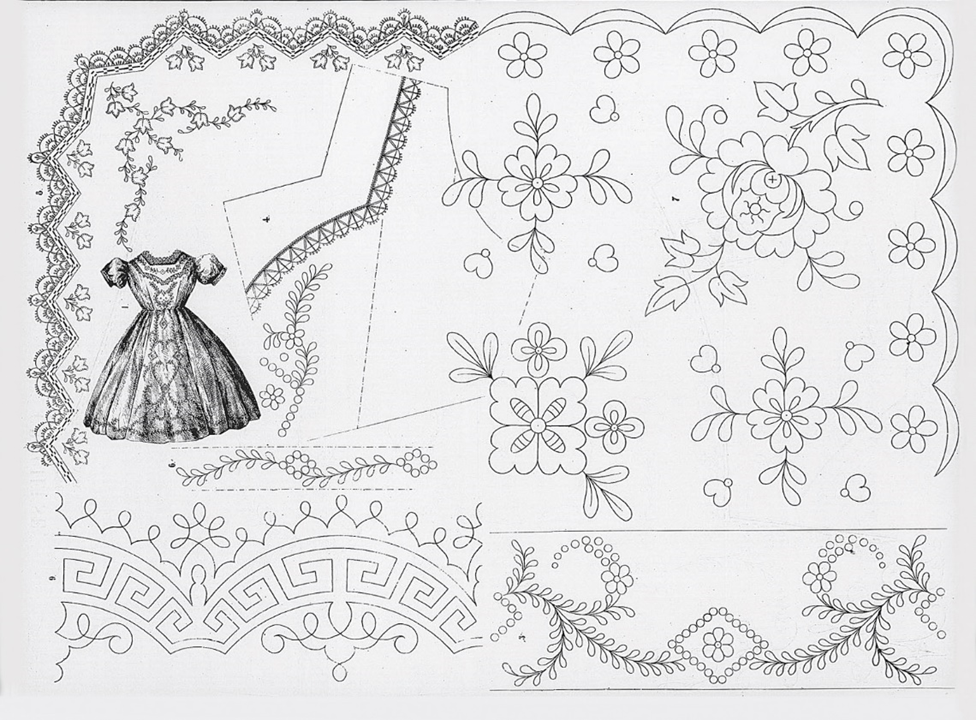

Figure 3: Embroidery designs from the Dutch magazine Gracieuse: Geïllustreerd Aglaja,1868, installment 3, p. 28. The floral motif at the top righthand corner is similar to the design found at the four corners of the embroidered square in figure 2. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Figure 3: Embroidery designs from the Dutch magazine Gracieuse: Geïllustreerd Aglaja,1868, installment 3, p. 28. The floral motif at the top righthand corner is similar to the design found at the four corners of the embroidered square in figure 2. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.The gold embroidery technique on this work and another similar cloth largely corresponds to what is found in European military and ceremonial embroidery. The latter has a heart-shaped motif surmounted by a fruiting stem at each of the four corners.12 The heart-shaped design is atypical and was probably adapted from European publications.

Similar styles of floral decoration are found on late 19th century batiks from the northern coast of Java. Certain Indo-Dutch batik designers held exclusive rights to reproduce designs from Dutch fashion journals, but artisans also copied the designs from printed sources for re-sale, resulting in the spread of popular imagery.13 In the case of needlework, embroiderers may have adapted patterns directly from the magazines themselves, or they may have purchased samplers (see figure 5) or sheet patterns from the artisans.

Figure 5: A beadwork sampler is a piece of embroidery that features a variety of stitches or motifs that serves as a model or reference. This sampler from either Singapore or Penang (c. 20th century) features a girl, a duck and flowers. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Figure 5: A beadwork sampler is a piece of embroidery that features a variety of stitches or motifs that serves as a model or reference. This sampler from either Singapore or Penang (c. 20th century) features a girl, a duck and flowers. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.BERLIN WOOLWORK

A large number of sheet patterns were created to cater to the growing interest in Berlin wool embroidery on counted thread canvas in 19th-century Europe. The threads of the canvas formed a grid-like ground for embroidery. At first, the designs, produced in Germany, were printed in black and white and then coloured by hand on a printed grid rather like graph paper. Each coloured square corresponded to a stitch of the same colour on the canvas. Rather like a pixelated image, more subtle shading could be achieved with a wider range of colours and more stitches (or squares) per centimetre.

The earliest themes were floral, but rapidly expanded to landscapes, historical ruins and mythical figures, and included designs based on paintings, such as English artist Edwin Landseer’s animal studies.14 The number of patterns grew equally quickly. In England alone, some 14,000 patterns were available by the late 1830s.15

Although its popularity had waned by the 1880s, Berlin woolwork was still carried out. In Singapore, imported printed patterns and sewing materials were distributed throughout department stores such as Robinson & Co.16 Probably aimed at a European clientele, these patterns soon penetrated the design repertoire of the nyonyas. Indicated by coloured squares, designs were easily copied on paper, or as embroidered samplers,17 many of which still survive to this day (see figure 5).

An Expanding World: Fairy Tales and Furry Animals

In the early 20th century, beadwork on counted thread canvas (fabric with a regular weave and small, regularly spaced “holes”) became widespread among nyonya embroiderers (see figure 4). The bright hues and wide colour spectrum of glass beads that could be purchased must have attracted Peranakan weavers, and the novelty and range of sheet patterns available likely also encouraged the adoption of this method.

Figure 4: A panel with glass bead embroidery on counted thread canvas, probably from Penang, early 20th century. The crested cockatoos, pansies, dahlias and forget-me-nots are motifs adopted from European woolwork patterns. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Figure 4: A panel with glass bead embroidery on counted thread canvas, probably from Penang, early 20th century. The crested cockatoos, pansies, dahlias and forget-me-nots are motifs adopted from European woolwork patterns. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.The nyonyas’ favourite designs of cabbage roses and rosebuds, lilies, flower baskets, birds, furry animals and girls in frocks circulated through samplers, either copied from friends or purchased, rather than in printed form (see figure 5). Based on designs that had been popular in Europe half a century earlier, the patterns may be considered anachronistic, but the themes and motifs are entirely consistent with the stories that were being introduced to the nyonyas at the time. A little background history is pertinent to our understanding here.

This coincided with the period when local intelligentsia such as Dr Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang, founders of the progressive Straits Chinese Magazine (1897–1907), were making efforts to champion education and literacy for women. But the idea faced resistance. Many Peranakan Chinese parents were concerned that formal education was either irrelevant or would lead to inappropriate or unbecoming modern behaviour. They agonised, for instance, “if the Nyonyas are properly educated, following Western ideas, they will resent the neglect of their husbands and take to something worse than gambling.”18

Nevertheless, by the early 20th century, a growing number of Peranakans started sending their daughters to school. The Singapore Chinese Girls’ School, aimed primarily at Peranakan Chinese girls, was founded in 1899 by Dr Lim and Khoo Seok Wan, another reform-minded local. Missionary educators also had an impact. Methodist missionary Sophia Blackmore taught the daughters of Tan Keong Saik, a wealthy Peranakan Chinese merchant, and established a school at Cross Street in Singapore, later to be renamed Fairfield Methodist Girls’ School. Elsewhere in the Straits Settlements and Dutch East Indies, basic formal education for women was slowly gaining acceptance too. The curriculum included reading and writing as well as hygiene and home-making skills to equip the girls to become good wives and mothers.

At school, the girls were introduced to European children’s literature. Newspaper reports, albeit brief, provide a sense of the growing interest in education for girls. At the Teluk Ayer Girls’ School prize-giving ceremony in 1906, a pupil read an excerpt from The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley.19 Eight years later in 1914, at another prize-giving ceremony, this time by the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School, one of the programmes featured girls (and a small number of boys) reciting popular English nursery rhymes.20 Anthologies of fairy tales, nursery rhymes and female explorers were distributed as prizes.

Local bookstores, such as G.H. Kiat at Change Alley and the Peranakan Chinese-owned Koh & Co at Bras Basah Road, sold similar titles.21 The motifs of puppies, kittens, swans, and little girls and boys, found in the imagery of rhymes, fairy tales and children’s stories, represented an extension of the expanding imaginary and real worlds of the young nyonya in the early 20th century.

From Images to Text: Cultural and Self Expressions

Around this time, the nyonyas’ newly acquired literacy also expressed itself more directly. A table cover (not illustrated in this article) in a private collection is beaded with unusually long text that reads:

Here’s to the bride and the bridegroom

We’ll ask their success in our prayers,

Through life’s dark shadow and sunshine

That good luck may ever be theirs.

Don’t worry about the future,

The present is all thou hast,

The future will soon be present

And the present will very soon be past.

The quatrains, relating to marriage and the passing of time, suggest the piece was made for a wedding and appear to have been copied verbatim, probably from a book of quotes and speeches.22 Supplementing or substituting conventional Chinese motifs, such phrases reiterate the nature of needlework designs as vehicles that conveyed benediction and good tidings.

Occasionally, embroidered text speaks of an individual’s identity. Figure 6 shows a beaded belt from Sumatra. At the upper border in the middle of the belt, two hands depicted in black emerge from a sawtooth pattern; the hands are clearly derived from newspaper advertisements where they were frequently used to draw attention to a headline. Here, they point to “KWEENGSOEN”, probably the name of the beader or the intended recipient of the belt, Kwee Ng Soen. Pots of flowers − all Chinese auspicious symbols – are aligned across the belt and identify it as culturally Chinese.

(Anti-clockwise from top) Figure 6: Belt with bead embroidery, West Sumatra, 1912. Pots of flowers – all Chinese auspicious symbols – are aligned across the belt and identify it as culturally Chinese in origin. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

(Anti-clockwise from top) Figure 6: Belt with bead embroidery, West Sumatra, 1912. Pots of flowers – all Chinese auspicious symbols – are aligned across the belt and identify it as culturally Chinese in origin. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Figure 7: A pair of men’s slippers with silver and silk thread embroidery, Penang, early 20th century. The words “Good Luck” are embroidered amidst the floral decorations. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Figure 8: A beaded carrying case from West Sumatra, early 20th century. The text “TJERiTALOTON” on this side of the case refers to Cerita Luotong, or Luo Tong Sweeps the North, a Tang dynasty military adventure. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Figure 9: Three-dimensional figurines and flowers made of wire, glass beads and gold thread (from a set of 14 pieces) used to decorate a sweetmeat box for the altar table. From Batavia (Jakarta), late 19th century. Collection of the Peranakan Museum.

But look closely and a pair of Dutch flags in the central cartouche declares Kwee Ng Soen’s allegience to the Dutch colonial government. They flank the number “1912” – the year after the Dutch and Chinese governments resolved their dispute over the nationality status of Dutch East Indies-born Chinese, allowing them to be considered as Dutch subjects rather than Chinese citizens within Dutch territory. Expressed through word and image, the belt is a striking comment on the tensions between cultural and political identity that confronted the overseas Chinese.

Much less complicated is figure 7, where the words “Good Luck” are embroidered amidst floral decoration on this pair of men’s slippers dating from the 1920s and 1930s.

Baba Malay Books and Nyonya Needlework

The Peranakan Museum has a small but significant number of nyonya accessories with beaded and embroidered figures from popular Chinese myths and legends. The most well-known figures in the Straits Settlements were the baxian or Eight Immortals, and Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West, while a wider selection was represented in needlework from the Dutch East Indies. Apart from Chinese embroidery pattern books, images found in Peranakan patois (Baba Malay) translations of popular Chinese classics may have provided ideas and inspiration for their depictions (see text box below).

The Baba Malay translations included full-page illustrations, sometimes by local artists, following the format of Chinese woodblock pictures.23 The names of the characters could be inscribed on the page to aid the reader, thus making them familiar with the iconography and depictions of figures from Chinese historical novels and legends.

Figures in flowing Chinese period robes and military costumes appear more frequently on needlework from the north coast of Java and Sumatra. Usually lacking specific attributes, most figures are difficult to identify. However, the imagery on a beadwork case from West Sumatra (see figure 8) can be discerned by the following text: “TJERiTALOTON” and “TjERiThoLOSiOE” (on the flip side). These refer to Cerita Luotong, or Luo Tong Sweeps the North, a Tang dynasty military adventure, and Hok Lok Siu or Fulushou, the Daoist deities representing prosperity, happiness and longevity.24

Figure 9 shows a set of three-dimensional beadwork figurines and flowers used to decorate a sweetmeat box (chanab) for the altar table. Acquired from a Peranakan Chinese family in Batavia (now Jakarta), these exceptional and delightful figures come replete with beards made of hair and crowns of beads and gold thread. The figures are said to represent the various male and female generals from Sie Djin Koei, another Tang dynasty story on the exploits of General Xue Rengui that was popular with the Peranakan Chinese.

Enchanted by the tales of valour, strategy, adventure and loyalty to the emperor, the Peranakan Chinese re-created their heroes and heroines in thread and beads. Inspired by the printed page, their embroidered images and words encoded moral values and virtues, and spoke of hopes, concerns, and of traversing cultures, in a Peranakan world.

PERANAKAN TRANSLATIONS OF CHINESE CLASSICS

Before the advent of cinema, outdoor performances and narrations by itinerant storytellers of excerpts from Chinese literature were popular entertainment for the Peranakan Chinese. In the late 19th century, local publishers began issuing translations of Chinese classics such as Water Margin (Song Kang) and Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sam Kok) in Baba Malay vernacular for a Peranakan Chinese reading public.

Chinese myths and legends have provided inspiration for nyonya needlework designs. This is an illustration of Cao Ren (spelled as Cho Jin in the book) from volume 2 of Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow”. Cao Ren was a military general from the late Eastern Han dynasty. All rights reserved, Chan, K.B. (1892–1896). Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow”. Singapore: Kim Sek Chye Press. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B00607830B)

Chinese myths and legends have provided inspiration for nyonya needlework designs. This is an illustration of Cao Ren (spelled as Cho Jin in the book) from volume 2 of Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow”. Cao Ren was a military general from the late Eastern Han dynasty. All rights reserved, Chan, K.B. (1892–1896). Chrita Dahulu-kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman “Han Teow”. Singapore: Kim Sek Chye Press. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B00607830B)

In the Dutch East Indies, children from wealthier Peranakan Chinese families were taught to read, and “women [nyonyas] quickly shared a taste for reading with the men”.25

The translations also found favour in the Straits Settlements. Lim Kim San, a former government minister in Singapore, recalls that his mother, a nyonya whose family was from Bengkalis in Sumatra, read Baba Malay translations of the Chinese classics.26

The author would like to thank Denisonde Simbol (Asian Civilisations Museum) and Jackie Yoong (Peranakan Museum) for providing the images used in this article.

Dr Cheah Hwei-Fe’n is an art historian with an interest in embroidery. She was a visiting researcher at the Centre of Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University, and was a guest curator of the exhibition “Nyonya Needlework: Embroidery and Beadwork in the Peranakan World”, which ended its one-year run at Singapore’s Peranakan Museum in June 2017.

Dr Cheah Hwei-Fe’n is an art historian with an interest in embroidery. She was a visiting researcher at the Centre of Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University, and was a guest curator of the exhibition “Nyonya Needlework: Embroidery and Beadwork in the Peranakan World”, which ended its one-year run at Singapore’s Peranakan Museum in June 2017.

NOTES

-

The term Peranakan means “local born” and generally refers to people of mixed Chinese and Malay/Indonesian heritage. Peranakan males are known as babas while females are known as nyonyas (or nonyas). ↩

-

Embroidery for the Peranakan kebaya in the rubric of “nyonya needlework” is not included in this essay as the former encompasses both hand and machine embroidery, and calls for a different disciplinary focus. Its evolution is superbly explored by Peter Lee. See Lee, P. (2014). Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan fashion in an interconnected world 1550–1950. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum. (Call no.: RSING 391.20899510595 LEE) ↩

-

Transferring the printed design onto fabric involved pricking tiny holes in the paper pattern along its outline and pouncing or dabbing charcoal or chalk powder through the holes onto the fabric. For an example, see Australia. Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. (n.d.). Embroidery pattern book, woodblock printed paper, China, 1875–1900. Retrieved from Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences website. ↩

-

Morrall, A., & Watts, M. (2008). English embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1580–1700: ‘Twixt art and nature’ (pp. 43–51, 61–63, 68–70, 86–90,152–156). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Call no.: RART 746.4409420903 ENG) ↩

-

See especially Speelberg, F. (2015, Fall). Fashion & virtue: Textile patterns and the print revolution, 1520–1620. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 73 (2). Retrieved from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website. ↩

-

Schäfer, D. (2015). Patterns of design in Qing-China and Britain during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In M. Berg, et al., Goods from the East, 1600–1800: Trading Eurasia (p. 107). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. (Call no.: RSEA 382.09504 GOO) ↩

-

Seet, B. (2009). Peranakan beadwork: My heritage. Singapore: Bebe Seet. (Call no.: RSING 746.508995 SEE) ↩

-

De Dillmont’s guide was first published by the producer of embroidery threads, Dollfus-Mieg & Cie (now DMC), in France in 1884. The English edition was released in 1886. See De Dillmont, T. (1996). The complete encyclopedia of needlework. Philadelphia: Running Press. (Call no.: RART 746.403 DIL) ↩

-

See for example, a handkerchief or tray cover with silk thread embroidery (Accession no.: 1995-2461), and two panels, possibly table covers, each with silk thread and gold thread embroidery, and a netted beadwork fringe along one edge (Accession nos.: 2005-1292 and 2005-1328). Retrieved from Roots.sg website. ↩

-

For examples, see a pair of slipper faces with silver thread embroidery (Accession no.: 2015-02101) and slipper faces embroidered with glass beads (Accession no.: 2015-02100). Retrieved from Roots.sg. website; Cheah, H-F. (2017). Nyonya needlework: Embroidery and beadwork in the Peranakan world (fig. 2.16, p. 39). Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum. (Call no.: RSING 746.44089951 CHE) ↩

-

See tray cover embroidered with gold and silver thread (Accession no.: 2012-00875). Retrieved from Roots.sg. website. ↩

-

Veldhuisen, H.C. (1993). Batik Belanda 1840–1940 = Dutch influence in Batik from Java history and stories (pp. 40–41). Jakarta: Gaya Favorit Press. (Call no.: RART q746.66209598 VEL) ↩

-

Barbara J. M. (2003), Victorian embroidery: An authoritative guide (pp. 20–21). Mineola, New York: Dover. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

See Ledbetter, K. (2012). Victorian needlework (p. 104). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Frederick Lender & Co. advertised Berlin Wool and Patterns, for Embroidery in The Straits Times, 26 November 1850, p. 2 (See Page 2 advertisements column 2); W. J. Allan & Co. at Raffles Place offered Madame Gouband’s Berlin-wool Instructions in The Straits Times, 21 September 1886, p. 2 (See Page 2 advertisements column 1); and Robinson & Co. advertised canvas (an evenweave fabric) for wool work in Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 18 September 1888, p. 1. ↩

-

A sampler refers to a piece of embroidery that features a variety of stitches or motifs that serves as a model or reference. For examples, see Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2016). A history of samplers. Retrieved from Victoria and Albert Museum website. ↩

-

Neo, P.N. (1907, December). Gambling amongst our nyonyas. The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental Culture, 11 (4), 150–153, p. 153. Singapore: Koh Yew Hean Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959. 5 STR; Microfilm no.: NL268) ↩

-

The Teluk Ayer Chinese Girls’ School (1906, January 20). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Chinese Girls’ School. (1914, January 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. At this event, Lim Boon Keng, one of the founders of the school, commented on the large number of pupils and the challenges of teaching English to pupils who spoke various other languages at home. ↩

-

G.H. Kiat stocked a range of books and magazines, including Weldon’s Ladies’ Journal and “English Fashion Books”, as well as Bible stories for children, fairy tales and nursery rhymes. See advertisements: Page 4 Advertisements column 1: Kim Kiat & Co. (1918, December 31). The Malaya Tribune, p. 4; Page 6 advertisements column 2: Beautiful gift books. (1923, December 11). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Titles offered by Koh & Co on Bras Basah Road included Bo-Peep, Aesop’s Fables, and My book of Best Fairy Tales. See Page 5 advertisements column 6: Gift books for X’mas presents. (1919, December 17). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Salmon, C. (Ed.). (2013). Literary migrations: Traditional Chinese fiction in Asia (17th-20th centuries) (pp. 257-258). Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. (Call no.: R 895.134809 LIT); On Chan Kim Boon’s translations of Song Kang and Sam Kok, see also Mazelan Anuar. (Jan–Mar 2016). A Chinese classic in Baba Malay. BiblioAsia, 11 (4), 54–55. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Asad Latiff. (2009). Lim Kim San: A builder of Singapore (p. 13). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (Call no.: RSING 363.585092 ASA) ↩