Rambling Around Bras Basah

It’s just a street to many, but for Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, the Bras Basah area is emblematic of how redevelopment can sometimes radically change the identity of an area.

The Rendezvous Restaurant at 4 Bras Basah Road was famous for its nasi padang cuisine. Photographed in 1982. Occupying the site today is the Rendezvous Hotel. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Rendezvous Restaurant at 4 Bras Basah Road was famous for its nasi padang cuisine. Photographed in 1982. Occupying the site today is the Rendezvous Hotel. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In the last 10 years that I’ve been working as an independent writer and curator on Singapore history, I’ve spent more time in the Bras Basah area than anywhere else on the island. I often spend weekdays at the National Library, National Museum or National Archives, and on weekends I’m often in the area too, at an art exhibition or a talk, or some other public event.

Until recently, my only childhood memory of Bras Basah was having Sunday lunch with my family at Rendezvous Restaurant in the early 1980s. The no-frills restaurant was located in a shophouse along the curve at the top end of Bras Basah Road, where Rendezvous Hotel stands today. Inside the restaurant – a fancooled coffee shop really – we would wash down plates of chicken korma and sayur lodeh with glasses of sweetened lime juice. Sometimes, after lunch we would take a gander at the second-hand bookshops a few shophouses down the road.

Does that paragraph sound nostalgic? I didn’t mean it that way, but given the speed of urban change in Singapore, it’s difficult to write about the recent past without inadvertently conjuring a world that is no more. Coffee shops selling local fare have been almost entirely expunged from the Bras Basah area, while the only “old” buildings left are those protected as heritage sites or national monuments. And in an age where digital media is king, the area’s bookshops have mostly vanished, though a handful still soldier on inside Bras Basah Complex.

When I think about Bras Basah, however, I don’t feel nostalgic or wistful. The Bras Basah I’ve come to know in the last 10 years has its own character – a living, functioning neighbourhood, very much of the present, that just happens to be found in an area shot through with history, even if much of it has been obscured by time, bias or neglect.

Exploring Bras Basah

I’ve come to know Bras Basah and the roads that lead off it from wandering around on foot. Due to the preponderance of one-way streets and no-right-turn signs in the area, not to mention heavy traffic, it’s often easier and faster to walk than to take public transport over a short distance.

At first glance, Bras Basah doesn’t seem particularly walkable in our sweltering climate: there is little shelter and one is largely confined to walking along the busy main roads. Still, there is some respite. St Joseph’s Church offers a serene little byway between Victoria Street and Queen Street, as does a sidelane that runs through the Singapore Management University (SMU) administration building, just behind NTUC Income Centre. On a rainy day, the underground walkways of Bras Basah MRT station offer a dry connection between Stamford Road and Bras Basah Road, but unless it’s absolutely bucketing down, I prefer to traverse the grassy lawns of the SMU campus aboveground. And if I’m walking south along Bras Basah Road towards Raffles City, I usually nip inside Chijmes, rather than take the well-shaded but narrow pavement that’s a little too close to traffic for my liking.

Above all, what makes Bras Basah so walkable is the pleasing symmetry of the distances between the streets. Each road or street is about 100 metres from the next, with wider sections no more than 200 metres long. On average, it takes 60 to 90 seconds for someone to walk an unobstructed 100 metres, which means that a pedestrian encounters, every so often, and with unfailing regularity, a new street and all that it entails: different architecture, a variety of sensory stimulation, a feeling of progress towards one’s destination, or, if nothing else, a sense of change and movement, even for someone walking aimlessly.

This also means that ambling down Bras Basah Road, a mere kilometre long, doesn’t feel as much of a hike as walking along an equally long stretch of Orchard Road, Shenton Way or Marina Boulevard. With its cross streets and unintentionally syncopated architectural landscape, Bras Basah possesses the kind of heterogeneity and interestingness that, according to urbanists like Jan Gehl, are so essential for creating healthy urban environments.1 It is also, thankfully, one of Singapore’s few downtown areas that isn’t saturated with brand names emblazoned across buildings, exhorting passers-by to come in and shop.

Indeed, the nice thing about the Bras Basah area is that it is full of little nooks where you can sit and think for a bit, without having to buy anything. There’s the soothing quiet of the Armenian Church (one of the oldest buildings in Singapore), the windy ground-floor atrium of the National Library, the benches at the ground floor of Bras Basah Complex facing Victoria Street, and the picnic tables scattered all over the SMU campus. More importantly, many of these spots are spacious and airy, and never feel cramped or claustrophobic. In a city-state of 5.6 million (and counting), finding space in the city to breathe – and to just be – can feel like a small mercy.

The Past in its Place

Then there is the invisible Bras Basah: the one that has been demolished, built upon, paved over and forgotten. As a place where human beings have been congregating for at least 200 years, if not more, the street has accumulated too many histories to be recounted here. Still, a few historical moments come to mind.

First, there is its name: Bras Basah is derived from beras basah, so the story goes, Malay for “wet rice” – referring to the rice grains left to dry on the banks of the stream that ran beside what is now Stamford Road.2 What stream, you ask? The stream that was engineered into the Stamford Canal in the 1870s, and thereafter rerouted, covered up and concealed from view.3 It flared briefly into public consciousness in 2010, when Orchard Road experienced a flash flood because part of the canal upstream was clogged by debris – a rather soggy reminder that for all of Singapore’s weatherproofing, there is a geographical, and specifically riverine, logic to this island that our modern systems of drainage ultimately depend on.4

Another longstanding but forgotten feature of Bras Basah is the 19th-century prison for convict labourers transported from British India. The prison complex was established between Bras Basah Road and Stamford Road in 1841, and expanded by the 1850s to occupy almost the entire site where SMU now stands. As architectural historian Anoma Pieris records in her book, Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: A Penal History of Singapore’s Plural Society, Singapore was – at the peak of convict movement in the 1850s – home to over 2,000 convict labourers, mostly men, though there were women too.5

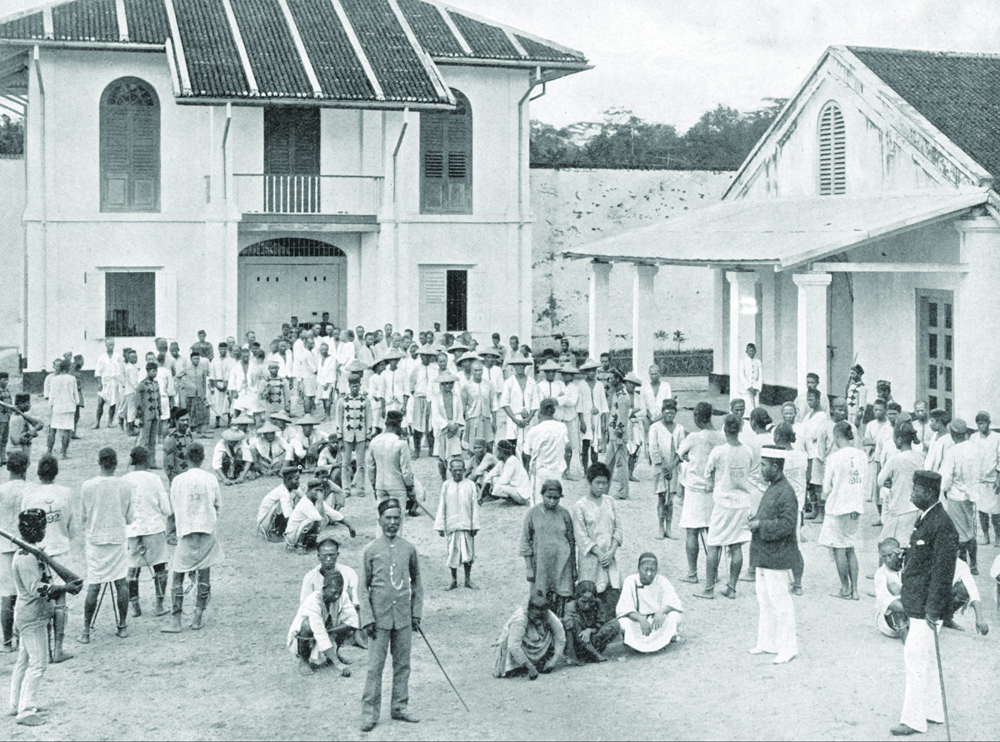

G.R. Lambert print of prisoners in the convict jail compound at Bras Basah, c.1900. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

G.R. Lambert print of prisoners in the convict jail compound at Bras Basah, c.1900. Illustrated London News Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Their backbreaking, unglamorous labour was the bedrock of numerous colonial construction projects, landmarks that we take for granted today: the roads near the Singapore River; the swampy land that was reclaimed into what is now Raffles Place and Collyer Quay; major roads from the town leading to Bukit Timah, Keppel, Thomson, Serangoon and Bedok; the Horsburgh and Raffles lighthouses; and, closer to Bras Basah Road, what are now national monuments such as the Istana, St Andrew’s Cathedral and Asian Civilisations Museum.6

Although the last group of convict labourers left Singapore in 1873, some of the prison buildings in Bras Basah remained intact until at least 1979 and were used for other purposes, notably military ones.7 As heritage blogger Jerome Lim discovered, prison buildings were used in the pre-war years by the Malay Company of the Singapore Volunteers Corps, during the Japanese Occupation by the Indian National Army, and after the war by British Indian troops and later their Malayan successors.8

SMU, which occupies a large swathe of Bras Basah today, bears no reference to the complex history of the area. This is not surprising as older, and accepted, narratives of Singapore history are known for overlooking, marginalising or even ignoring the experiences of early migrants, particularly non-Chinese ones, who did not put down roots or luck out with a rags-to-riches success story in Singapore. Those who spent a significant amount of time here slaving away on roads and buildings but left no family, wealth, roads or place names behind, barely merit a mention in that narrative.

Interestingly, some Indian convict labourers – notably “First Class” convicts with exemplary track records – did settle down in Singapore after completing their prison sentences. They became, the British observed, “very useful men in the place – cart owners, milk sellers, road contractors and so on: many of them comfortably off.”9 Perversely, there are no bronze sculptures commemorating their labour and history at Bras Basah or near the Singapore River, where their human toil was so essential to the smooth functioning of the colonial port in its early years.10

The former St Joseph’s Institution building at Bras Basah Road facing the field, which later became Bras Basah Park, c.1910. The building is currently occupied by the Singapore Art Museum. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The former St Joseph’s Institution building at Bras Basah Road facing the field, which later became Bras Basah Park, c.1910. The building is currently occupied by the Singapore Art Museum. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.So much for the past. The latest state-decreed incarnation of Bras Basah proclaims it as the “arts, culture, learning and entertainment hub for the city centre”.11 Around 2005, urban planners came up with the clumsy portmanteau Bras Basah.Bugis (the selfconscious full-stop immediately dooming whatever “hip” quotient the planners were trying to inject to the area).12 After deliberate efforts in the 1980s to move schools such as St Joseph’s Institution and Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus away from this part of the city, the government introduced new ones – the School of the Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts and SMU – in a deliberate strategy to bring artistic endeavour and young people back into the area.13 With events such as the National Museum’s Night Festival – which gets bigger and seems to require more road closures each year – there are plenty of official efforts to entice people into spending time here again.

But it is difficult to love a place when you know it can be snatched away by the powers that be. In my mind, two related offences have been wrought on Bras Basah in the last 20 years. The first was the demolition of the much-loved National Library building at Stamford Road, which was carried out in 2005 despite a groundswell of public protestations, a flurry of newspaper articles and parliamentary debates, and viable alternatives proposed by knowledgeable architects.14

Did it matter that the building had been funded by philanthropist and community leader Lee Kong Chian, thus creating Singapore’s first free public library? Did it matter that the library had provided a haven for the post-war generation of students from schools in the area – a place where they studied and eventually acquired the knowledge and skills that contributed to their young nation’s development?15

But it was more important, according to transport planners, to have a concrete tunnel bored through Fort Canning Hill in order to create “the most direct route for traffic moving from Marina Centre and the Central Business District to Orchard Road”, and also to “open up the vista” to the hill. Moreover, the government would re-align Stamford Road to “provide SMU with more regular land parcels to work with”.16

Walking along the right (northeast) side of Stamford Road from Raffles City, over the paved-over Stamford Canal past the Land Transport Authority and SMU buildings, one sees no such vista of the hill today. At the foot of the hill, a pair of despondent pillars from the original compound commemorate the former National Library. They sit mutely at the rear of SMU, which in 2005 took over the open fields between Bras Basah Road and Stamford Road. Before that, Bras Basah Park was a much appreciated green lung in the city; its grounds were used by both the boys of nearby St Joseph’s Institution (which now houses the Singapore Art Museum) and the public for sports events, school camps, romantic liaisons or other tomfoolery.

In a parliamentary debate in 2000 on the planned demolition of the National Library, then Minister for National Development Mah Bow Tan added, by way of consolation, “We will also encourage SMU to incorporate in the design of its buildings features that would help Singaporeans evoke memories of the Library.”17 There was talk that SMU would become the New York University or London School of Economics of Singapore – a campus that engaged with the city, whose students and intellectual life would create a vibrant neighbourhood. This, it was implied, would compensate for the loss of greenery and open views, so rare in Singapore, and especially so downtown.

But when the SMU campus buildings emerged, they were uninspiring and showed no relation to the former National Library. Even today, its students seem to vanish into the buildings, and the campus often seems deathly quiet and deserted all year round. When I pass by its neatly manicured lawns or cleanly swept atria, I think about the green fields that the university replaced, and I can’t help but wonder if the university couldn’t have been located, well, anywhere else, really – while the city would have been better served by retaining those fields as a miniature Central Park in downtown Singapore.

Whither Bras Basah?

Bras Basah will, no doubt, remain a contested space in years to come. Given its location and a rich architectural history that fulfils a certain neocolonial narrative, it will never drop out of sight or the attention of the authorities. Thus it can never truly belong to anyone who loves the place, or to the people who live or work there – and mind you, some residents of Bras Basah Complex and Waterloo Centre have been there since 1980. I’m sure it’s only a matter of time before another urban planner comes up with a “masterplan” to make the area more “vibrant”, regardless of the desires or needs of the people who inhabit the space.

Yet, to walk the city is to know it in a way that is, arguably, antithetical to the way urban planners see it as a Cartesian or Euclidean space. When I walk around Bras Basah, I see the multiple layers of history – visible and invisible – and I am grateful for what is there that is real: Mary’s Kafe inside Kum Yam Methodist Church, where Eurasian aunties serve home-made Eurasian food and sugee cake; the stationery and bookshops of Bras Basah Complex, where the owners might chat about their grandchildren in between serving customers.

When I stand at the junction of Hill Street and Stamford Road outside Stamford Court – ironically, as you’ll see, the home of the National Heritage Board today – I think about the splendid Eu Court that used to stand on the site. It was one of the first apartment buildings in Singapore and admired for its neoclassical architecture and hand-blown glass windows, before it was torn down in 1992 to make way for the widening of Hill Street – another victim of a certain vision of urban “development”.18

I stand, I look, I feel and I think. And I know it can all go away in a minute.

This 1984 photograph shows Eu Court at the corner of Stamford Road and Hill Street. Built in the late 1920s by prominent businessman Eu Tong Sen, it was demolished in 1992 to make way for road widening. Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.

This 1984 photograph shows Eu Court at the corner of Stamford Road and Hill Street. Built in the late 1920s by prominent businessman Eu Tong Sen, it was demolished in 1992 to make way for road widening. Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore. Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

NOTES

-

See for instance Ellard, C. (2015, September 1). Streets with no game. Aeon. Retrieved from Aeon Media Group Ltd. website. ↩

-

Victor R. Savage and Brenda Yeoh offer a more thorough explanation in their book. See Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (p. 47). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV) ↩

-

For details, see Chng, G. (1984, April 22). The disappearing canal. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Liang, A. (2010, June 18). Blocked drain caused Orchard Road flood. My paper. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Pieris, A. (2009). Hidden hands and divided landscapes: A penal history of Singapore’s plural society (pp. 87, 89, 243). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (Call no.: RSING 365.95957 PIE) ↩

-

Pieris, 2009, pp. 33, 99; National Library Board. (2018, January 29). Indian convicts’ contributions to early Singapore (1825–1873) written by Vernon Cornelius-Takahama. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. Historian Clare Anderson writes that in the 19th century, “the East India Company used and supplied convicts in preference to and to replace slaves” in Southeast Asia (italics original); “convicts were not an alternative to free labour, but the first choice to build infrastructure” because they were “cheaper and more efficient, and certainly a more flexible and controllable alternative” to other forms of labour. See Anderson, C. (2016, August 31). Transnational histories of penal transportation: Punishment, labour and governance in the British imperial world, 1788–1939. Australian Historical Studies, 47 (3). Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩

-

Pieris, 2009, p. 192; T. F. Hwang takes you down memory lane. (1979, April 7). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, J. (2016, February 20). The fight for freedom from where freedom had once been curtailed. Retrieved from The Long and Winding Road blog. ↩

-

The bronze sculptures along the Singapore River are primarily about European and Chinese traders, with Chinese and Indian labourers working in the background. Indians are depicted as coolies, although there is one Chettiar. ↩

-

Tor, C.L. (2005, July 5). $46m makeover for Bugis. Today, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The first mention of “Bras Basah.Bugis” in the English press is in Tee, H.C. (2004, December 11). Model City. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. See also Today, 5 Jul 2005, p. 6. ↩

-

Tan, D.W. (2008, September 14). Old district a hive of activity. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. In the 1980s and 1990s, 13 schools were relocated from the Bras Basah area (in alphabetical order): Anglo-Chinese School (Primary), Catholic High (primary and secondary), Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ, primary and secondary), CHIJ St Nicholas Girls’ School (primary and secondary), St Anthony’s Boys’ School, St Anthony’s Canossian (primary and secondary), St Joseph’s Institution, Stamford Primary School and Tao Nan School. ↩

-

See for instance Ideas to save library building. (1999, March 20). The Straits Times, p. 42; Tan, S.S. (1999, March 20). Consider a change of plans before it is too late. The Straits Times, p. 57; Kraal, D. (1999, March 31). Hurrah for the new voices. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Parliament. (2000, March 6). Official reports – Parliamentary debates (Hansard). National Library (Retention). (Vol. 71, col. 1137). Retrieved from Parliament of Singapore website. ↩

-

Singapore Parliament. Official reports – Parliamentary debates (Hansard), 6 Mar 2000, cols. 1134, 1136. ↩

-

Singapore Parliament. Official reports – Parliamentary debates (Hansard), 6 Mar 2000, col. 1134. ↩

-

Ho, J.B.E. (1991, March 20). Re-examine once more plan to destroy Eu Court. The Straits Times, p. 30; Tan, C. (1992, August 18). Going, going… almost gone. The Business Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩