The Road to Nationalisation: Public Buses in Singapore

From as many as 11 bus companies to just one bus operator by 1973. Lee Meiyu chronicles the early turbulent days of Singapore’s bus industry.

“We went to their workshops. We audited their books. In three months, we… revealed that despite the alleged amalgamation of the old bus companies, this was only a paper unification – the old owners were still running little fiefdoms within the company.”1

– Wong Hung Khim, Chair of the Government Team of Officials

This was the scenario that government officials faced in May 1974 when they reviewed the workings of Singapore Bus Service (SBS) – formed just a year earlier to consolidate and provide better bus services for the public. When the government found out that SBS was dragging its feet over the restructuring process, it took matters into its own hands by assembling a team of civil servants (known as the Government Team of Officials or GTO) to take over the management of the bus company. This action essentially triggered the nationalisation of Singapore’s public bus service system.2

The clean and air-conditioned public buses that we take for granted today were unheard of back in the 1950s and 60s. Commuters recalled being “fried in the sun” or “soaked in the rain” by turns as they battled with grimy and scratched bus windows that could not be properly opened or shut. Crowded buses were also a haven for pickpockets, and the cramped conditions became worse when people squeezed themselves through open windows in order to hitch a ride during peak hours. Not surprisingly, tempers would fray and scuffles break out on board.3

(Left) The scene at a bus stop before the queue campaign by the Singapore Traction Company, 1960s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Left) The scene at a bus stop before the queue campaign by the Singapore Traction Company, 1960s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.(Right) A bus conductor of the Singapore Traction Company at work, 1960s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

To add to the passengers’ woes, these creaky and hot (read, non-air-conditioned) buses spewed choking exhaust fumes as they rattled and honked their way up and down busy streets. Buses would break down frequently, and often arrived late or did not show up at bus stops at the designated time. To make matters worse, the drivers’ punishing schedules – working two shifts a day with no breaks – led some to resort to desperate measures, such as puncturing their own bus tyres, so as to get some rest while awaiting repairs. In early 1974, it was reported that 400 buses were out of service at any one time, and out of 1,450 buses in operation, an average of 800 buses would break down in a day.4 In short, the bus transport system was in shambles.

In the meantime, SBS’s management team had other, more pressing problems to resolve. Before 1971, buses here were operated by the British-owned Singapore Traction Company (STC) and another 10 Chinese-owned companies. These 11 bus companies were later merged into four, and finally into one – SBS – in 1973 under the directive of the government.

Two buses belonging to the Singapore Traction Company, 1950s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Two buses belonging to the Singapore Traction Company, 1950s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.However, as the leader of the GTO, Wong Hung Khim, later recalled, the gangster connections and thuggish behaviour of these Chinese-owned companies of the past persisted when SBS was created. Wong personally received an anonymous letter threatening harm to him and his family if the GTO probed too deeply. High-ranking law enforcement officers such as Yap Boon Keng, then Assistant Commissioner of Police, were brought in to beef up the team so that the GTO had the clout and political heft to get down to the serious business of restructuring the company.5

A Chaotic Start

Public motor buses for commuters were introduced into Singapore as early as 1919. Nicknamed “mosquito buses”, these unlicensed vehicles were small, seven-seater omnibuses that weaved dangerously in and out of traffic, frantically looking out for passengers − much like bloodthirsty mosquitoes looking for prospective prey. Operated by enterprising Chinese individuals, the mosquito buses primarily serviced rural and suburban areas that were out of the reach of STC’s trolley buses,6 at times even encroaching on the latter’s routes.

A trolley bus at the junction of Stamford Road and Hill Street in the late 1920s advertising its services as an economical way of commuting. Trolley buses, which operated between 1926 and 1962 in Singapore, were electric buses that drew power from overhead wires suspended from roadside posts using trolley poles. They were eventually replaced by buses with motor engines. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A trolley bus at the junction of Stamford Road and Hill Street in the late 1920s advertising its services as an economical way of commuting. Trolley buses, which operated between 1926 and 1962 in Singapore, were electric buses that drew power from overhead wires suspended from roadside posts using trolley poles. They were eventually replaced by buses with motor engines. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1929, STC introduced its own motor bus fleet to compete against the mosquito buses. Singapore’s public bus transport system became a rapidly growing network radiating from the city centre, with STC buses operating in town and mosquito buses servicing the outskirts. Despite this seemingly well-connected system, commuters found it a nightmare to travel by bus. Each bus company controlled its own territory and set its own rules and regulations, timetables, as well as routes and fares. As a result, commuters wasted time and money waiting and transferring between different buses just to get to their final destinations.7

In an attempt to regulate the mosquito buses, the Registrar of Vehicles issued Chinese bus operators with licences to legally ply routes not serviced by STC. However, as the Municipal Ordinance of 1935 ruled that only certified companies could be issued with licences, this forced individual operators to organise themselves into 12 bus companies – STC and 11 Chinese bus companies.

A mosquito bus in between a taxi and a cyclist, 1935. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A mosquito bus in between a taxi and a cyclist, 1935. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.A period of expansion soon followed, but this was accompanied by failed attempts at further regulatory controls, as well as growing public dissatisfaction with the bus transport service. There was a lull period when Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. After the war, whatever bus companies that survived the Japanese Occupation scrambled to get back on their feet.8 This situation continued until 1951, with 10 Chinese bus companies, along with STC, servicing commuters.9

1919–1930s

• Singapore Traction Company (established in 1925)

• Mosquito buses (unlicensed)

1930s–1970

• Singapore Traction Company

• Kampong Bahru Bus Service (established in the 1930s)

• Tay Koh Yat Bus Company (established in 1932; absorbed Seletar Motor Bus Company by 1940)

• Changi Bus Company (established in 1933)

• Green Bus Company (established in 1934; absorbed Jurong Omnibus Service in 1945)

• Katong-Bedok Bus Service Company (established in 1935)

• Paya Lebar Bus Service (established in 1935)

• Keppel Bus Company (established in 1936)

• Punggol Bus Service (established in 1936)

• Easy Bus Company (established in 1946)

• Hock Lee Amalgamated Bus Company (formed in 1951 from a merger between Ngo Hock Motor Bus Company, established in 1929, and Soon Lee Bus Company, established in 1931)

1971–1972

• Singapore Traction Company (ceased operations in 1971)

• Amalgamated Bus Company (formed from a merger of Hock Lee, Keppel Bus and Kampong Bahru in 1971)

• Associated Bus Services (formed from a merger of Paya Lebar, Changi, Katong-Bedok and Punggol in 1971)

• United Bus Company (formed from a merger of Tay Koh Yat, Green Bus and Easy Bus in 1971)

1973

• Singapore Bus Service (merger of Amalgamated, Associated and United bus companies)

1940s and 50s: A Tumultuous Era

Public bus services in the late 1940s and 50s were marred by corruption and worker strikes. Dubbed as “The Squeeze”, the corruption took many forms:

“… with the most common being the issue of a ticket of a lower face value than of an actual fare being paid, with the difference being pocketed by the conductor. Then there was the collecting of used tickets from passengers as they alighted in anticipation of resale, time and time again… A third method was for the collection of fares as the passengers alighted, without the issue of any ticket… This was a highly organised system of theft, and those involved would need the cooperation of other employees… and shares for drivers, ticket clerks, time keepers and the like had to be allowed for… so lucrative… that it was said at the time that any man seeking to be employed as a conductor would be willing to pay something like fifty dollars ‘coffee money’ to the right person in order to obtain a job.”10

Worker strikes supported by two trade unions – Singapore Traction Company Employees’ Union and Singapore Bus Workers’ Union – were common, the most serious being the “Great STC Strike” of 1955. STC’s refusal to increase wages in July 1955 resulted in a 142-day strike by workers demanding increased pay and better welfare, with employees from Chinese bus companies joining the fray in November.

STC’s union had earlier given formal notice to management that if their demands were not met, all its workers would go on strike in September. Bus garage entrances were blocked by picket lines and banners depicting the wicked actions of greedy shareholders (such as European bosses whipping cowed employees harnessed to buses) were hung along boundary fences.11

The Chinese bus companies were the first to reach an agreement with the Singapore Bus Workers’ Union and resumed their bus services in December 1955, while protracted negotiations with STC workers continued. An agreement to end the STC strike was finally reached on 15 February 1956, and its workers resumed work the following day. At the time, no one would have guessed that these events would put an end to the 30-year monopoly held by STC, and subsequently contribute to its demise some 16 years later.12

The Commission of Inquiry formed by the government to review Singapore’s public transportation system observed a number of issues with the public bus service, including overcrowding, corruption, lack of coordination among the different bus companies on routes and fares, inadequate staff training, long working hours, and poorly maintained buses. The Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Public Passenger Transport System of Singapore, published in 1956, also known as the Hawkins Report, recommended a radical move 13 – the nationalisation of Singapore’s public bus service. This would set off a chain of events over the next 17 years.14

“PIRATES” TO THE RESCUE!

Imagine having no public buses or trains running for a month. How would you travel to work or school?

This is what happened during the “Great Strike” of 1955 when bus workers in Singapore refused to turn up for work. Commuters resorted to one of the earliest modes of passenger transport in the colonial history of Singapore – trishaws – and another, more recent service: “pirate” taxis.

Viewed as a menace by the government, pirate taxis were unlicensed vehicles offering transportation services to the public, much like the mosquito buses of the past. (Ironically, bus companies also resented pirate taxis as they ate into their profits.) With frequent disruptions and lack of route coordination in the public bus service, pirate taxis became a necessary evil that kept people in Singapore, small as the island may be, on the move.

From Eleven Companies to Three

Singapore’s changing political landscape over the next decade would delay the nationalisation process as the newly formed government paid attention to more urgent issues such as housing. The next landmark study on public bus services was the 1970 White Paper titled Reorganisation of the Motor Transport Service of Singapore, which also recommended conducting a separate study on the coordination and rationalisation of bus routes. This led to the Wilson Report, or A Study of the Public Bus Transport System of Singapore, in the same year.15

Both reports recommended that the first step towards nationalising public bus services was to merge the 10 Chinese bus companies into three regional companies servicing the eastern, northern and western parts of Singapore, alongside a reorganisation of STC (to continue servicing the central sector), which had been suffering severe operating losses. In addition, the Wilson Report also provided detailed recommendations for bus routes, frequencies, fares, vehicle design and models, design infrastructure for bus stops and terminals, and maintenance standards.16

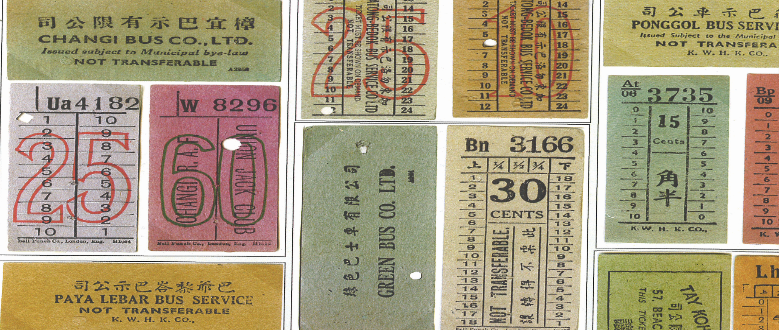

Pre-1971 bus tickets issued by the 10 Chinese bus companies. All rights reserved, York, F. W., & Philips, A. R. (1996). Singapore: A History of its Trams, Trolleybuses and Buses Vol 2: 1970s and 1990s (pp. 18, 45). Surrey: DTS Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 388.41322095957 YOR).

Pre-1971 bus tickets issued by the 10 Chinese bus companies. All rights reserved, York, F. W., & Philips, A. R. (1996). Singapore: A History of its Trams, Trolleybuses and Buses Vol 2: 1970s and 1990s (pp. 18, 45). Surrey: DTS Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 388.41322095957 YOR).On 11 April 1971, the 11 existing bus companies were reorganised into four entities: Amalgamated Bus Company, Associated Bus Services, United Bus Company and STC. In a sudden turn of events, STC, the oldest bus company among the four, announced in December the same year, only nine months after the amalgamation, that it would cease operations. STC − which once owned the largest fleet of trolley buses in the world – had suffered staggering losses, contributed in part by its own systemic organisational problems and increasing competition as a result of losing its business monopoly.17 STC’s demise was sealed when it was acquired by the other three bus companies.18

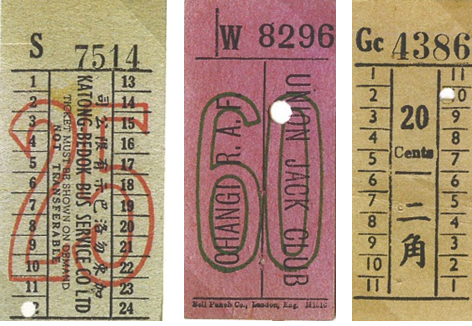

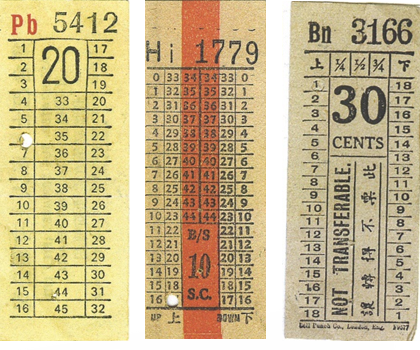

Bus tickets issued by United Bus Company, Associated Bus Services and Amalgamated Bus Company between 1971 and 1973. All rights reserved, York, F. W., & Philips, A. R. (1996). Singapore: A History of its Trams, Trolleybuses and Buses Vol 2: 1970s and 1990s (pp. 18, 45). Surrey: DTS Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 388.41322095957 YOR).

Bus tickets issued by United Bus Company, Associated Bus Services and Amalgamated Bus Company between 1971 and 1973. All rights reserved, York, F. W., & Philips, A. R. (1996). Singapore: A History of its Trams, Trolleybuses and Buses Vol 2: 1970s and 1990s (pp. 18, 45). Surrey: DTS Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 388.41322095957 YOR).The fate of the remaining three companies also hung in the balance: they competed instead of cooperating with one another, and there was no standardisation of fares, services and schedules. In short, the amalgamation of public bus services was only in name but not in spirit, and the government was fast losing its patience.19

CHINESE BUS COMPANIES

Chinese-owned bus companies in Singapore have a long history that predates the 1930s. The early owners were mainly immigrants of Fuqing and Henghua origins from Fujian province in China. Most started out as rickshaw drivers, menial labourers or hawkers and, after several years of hard work and frugal living, ventured into the transport business.The “business” began by a few trusted “insiders” pooling their capital – family members or individuals from the same village area in China, for example. Often, the money was used to buy a mosquito bus and, depending on the amount of funds contributed, one person could own half the vehicle while another owned two wheels. Profits were prorated according to the amount invested.

Compared with the Singapore Traction Company, which was run by an international company based in London, Chinese bus companies were organised along “clannish” and informal lines − and managed in a laissez-faire manner based on trust among friends and kinsmen. It was only in the 1930s that other Chinese dialect groups were able to penetrate the Fuqing- and Henghua controlled Chinese bus service industry.

Despite the growth of Singapore’s public transport industry over the next 40 years, the informal management style of Chinese bus companies persisted. This became a problem in the 1970s when there was a dire need to modernise the public bus system to support Singapore’s rapidly growing population and economy.

From Three Companies to One

“The picture as presented during 1972… Everywhere the traveller went there were breakdowns: a broken down bus did little to assist the concept of the “green” city… the conductor was required to remove a seat cushion to place some distance behind the failed bus, adding a branch of a tree to act as an additional marker. The roadside vegetation took terrible punishment for a time, whilst personal experience was to reveal that not always were the cushions returned once the bus was back in service.”20

A bus conductor on duty in the 1970s. The Theatre Practice Ltd Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A bus conductor on duty in the 1970s. The Theatre Practice Ltd Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. A bus conductor’s ticket punch from the 1960s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A bus conductor’s ticket punch from the 1960s. F W York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.With little progress made by bus companies on the recommendations put forward by the aforementioned reports, deteriorating bus services became the subject of a parliamentary debate on 12 March 1973. Several members of parliament pointed out the frequent breakdowns, reckless driving and the poor service mentality of bus workers in general. A letter by a L.P.H. published in The Straits Times on 16 March 1973 also noted that long drives without rest, made worse by “boneshaker buses”, the tropical heat, traffic congestion, and the smell and fumes from old engines contributed to drivers’ fatigue and did little to boost the morale of bus workers.21

Left with no choice, the government announced the merger of the three bus companies to form Singapore Bus Service (SBS) on 1 July 1973. It was believed that a single bus operator would help eliminate the problems of wasteful competition, lack of standardisation, and duplication in route services that had dogged public bus services since the very beginning. Not unexpectedly, the merger began on a rocky note as shares of SBS were still held by the former Chinese bus companies, with allocation based on the relative sizes of the companies prior to the amalgamation in 1971. In other words, SBS was a cooperative – and not a single entity – run by 10 different companies.

The mammoth task of reorganising and overhauling SBS’s operating structure and culture was left to a task force of senior civil servants known as the Government Team of Officials (GTO) in May 1974. Appointed by then Minister for Communications Yong Nyuk Lin, the team − comprising Wong Hung Khim, Yap Boon Keng, Ang Teck Leong, Yeo Seng Teck, Lo Wing Fai, Ong Chuan Tat and Mah Bow Tan − was seconded to SBS to oversee the transformation.22

A New Beginning

On 20 July 1974, the GTO submitted its report, Management and Operations of Singapore Bus Service Ltd: Report of Government Team of Officials, to Yong, recommending that SBS be nationalised. The report summed up the findings thus:

“It is clear that while many of the problems facing SBS were inherited, management weakness resulting in lack of control and supervision at every level is the root cause of its inability to provide a clean and efficient service. Staff morale is low because of poor working conditions. On the other hand, slack discipline has resulted in wide-spread malingering, unjustifiably high charges on overtime and poor standards of maintenance and service… we are of the opinion that if SBS is left to run on its own, the quality of our public bus service will deteriorate still further… There appears, therefore, no other option at the moment but for the Government to assist by seconding such number of Government Officials as it can spare while the rest can be directly recruited.”23

The government accepted the findings and recommendations of the GTO. The first priority was to institute a new organisational structure with checks and balances in place to break up the “little conglomerates” formed under the previous structure. New departments, such as human resources, finance, operations and planning, and warehouse and logistics, were also established.24

Corruption and unaccountability rampant at all levels had to be quickly eradicated. For example, the GTO discovered, to their horror, that the daily collections of coins, concession cards and bus tickets were kept unlocked in branch offices and depots without proper accounting and security measures in place. Anyone could help themselves to the money and items. Section managers had their own vested interests; they ran their own hardware businesses or petrol stations outside of work, and frequently made purchases on behalf of the company without proper quotes or tenders.25

The GTO went to work. One of the first things they did was to destroy all bus tickets and print new ones, after which takings went up dramatically. They kept records, computerised takings and closely monitored staff. There was some initial resistance at first from not just SBS management and staff, but also from government departments. With the backing of then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, the GTO managed to resolve matters with the government departments, and also worked closely with the unions to bring order and discipline back to the workforce. Khoo Ban Tian of Malayan Banking was approached to provide a loan of several million dollars as an emergency fund to tide the company over.26

The government mobilised a team of trained mechanics from the Singapore Armed Forces to repair and maintain the company’s buses and equipment. The SAF team did such a good job that the number of breakdowns was reduced drastically, from 800 a day in 1974 to just 145 in 1976.

Other government departments were pulled in to help as well. A former Registry of Vehicles staff, Phua Tiong Lim, recalled the confusion when many bus routes were changed to streamline the network of services. When printed copies of the new bus guides ran short, the army’s Transport Logistics Unit was enlisted to roam the streets and pick up hapless passengers who did not know how to get home.27

To address the issue of low staff morale, staff facilities and training were provided, incentives for honest and hard work were established, and a standardised structure of salary and staff benefits was introduced. The addition of new buses and workshops, and the rationalisation of bus routes, took longer to achieve, but when these improvements kicked in, they vastly improved SBS’s service standards and enhanced passengers’ experiences.

The transformation of SBS was so successful that the government decided to list it on the Singapore Stock Exchange in 1978 as Singapore Bus Service Limited. By the end of 1979, the government decided that SBS was in good hands and withdrew its team of 38 officers (of whom 19 chose to remain) seconded to the company.28 In 2001, SBS was renamed SBS Transit Limited to reflect its new status as a bus and rail operator.

Making a Case for Nationalisation

Before the 1970s, Singapore’s public bus industry was a freewheeling, unregulated market controlled by 11 rival bus companies vying for passengers. Each company jealously guarded its own turf, and determined its own rules, schedules and fares. Commuters had to put up with frequent vehicle breakdowns, cramped buses and confusing routes. Corruption was rife among bus workers, and labour unrest resulting in worker strikes and stoppage of work was commonplace.

The nationalisation of the public bus service in 1973 was a key milestone in the history of public transport in Singapore. More significantly, it marked the government’s first – and much needed – intervention in the affairs of privately owned companies that could not competently provide essential public services.

This episode in Singapore’s history is also an example of the bold and decisive moves taken by the nation’s first generation of civil servants in ensuring the survival of a resource-poor and newly independent island. Singapore’s public transportation system would not be the model of efficiency it is today without such top-down intervention in the nascent days of its history.

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection. Her research interests include Singapore’s Chinese community. She is co-author of Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants (2012) and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – a Resource Guide (2013).

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection. Her research interests include Singapore’s Chinese community. She is co-author of Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants (2012) and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – a Resource Guide (2013).

NOTES

-

Sharp, I. (2005). The journey: Singapore’s land transport story (p. 49). Singapore: SNP International Publishing Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 388.4095957 SHA) ↩

-

Sharp, 2005, pp. 47–49; Ng, G.P. [2001]. The green bus co. ltd. (1919–1971): A chinese family business in Singapore (p. 24). Singapore: National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 388.3220655957 NG) ↩

-

Trolley buses, which were in operation in Singapore from 1926–1962, were electric buses that drew power from overhead wires suspended from roadside posts using trolley poles. ↩

-

York, F.W., & Philips, A.R. (1996). Singapore: A history of its trams, trolleybuses and buses vol 1: 1880’s to 1960’s (p. 43). Surrey: DTS Publishing Ltd. (Call no.: RSING q388.41322095957 YOR); Sharp, 2005, p. 47; Ng, 2001, pp. 8–9. ↩

-

Bus companies that used to provide express services from Singapore to Malaysia (such as the Kuala-Lumpur-Singapore Express Limited, Sing Lian Express Limited, Singapore-Johore Express Limited) and school buses are not covered within the scope of this essay. ↩

-

Ng, 2001, pp. 9–10; York, F.W., Davis, M., & Osborne, J. (2009). Singapore: A history of its trams, trolleybuses and buses vol 2: Buses and bus services 1970s and 1990s (pp. 8, 53, 67). Croyden: DTS Publishing Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 388.41322095957 YOR) ↩

-

York & Philips, 1996, p. 71. ↩

-

York & Philips, 1996, pp. 93, 99, 110. ↩

-

York & Philips, 1996, pp. 95, 96, 100, 108, 112, 116. ↩

-

The nationalisation of Singapore’s public bus service was first mentioned in a 1953 report by the Public Passenger Transport Committee of the City Council, which recommended acquiring the STC and bringing the private bus companies together under the control of a single government entity. However, no concrete actions were taken. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore. (1956). Report of the Commission of inquiry into the public passenger transport system of Singapore (pp. 1, 26, 31, 35, 44, 47, 69, 71, 74). Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 388.3 SIN) ↩

-

Wilson, R.P. (1970). A study of the public bus transport system of Singapore (p. 1). Singapore: Government Printer. (Call no.: RCLOS 388.3220655957 WIL); Singapore Registry of Vehicles. (1970). Reorganisation of the motor transport service of Singapore (p. 11). Singapore: Printed by the Government Printer Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 388.31 SIN) ↩

-

Wilson, 1970, pp. 3, 7; Singapore Registry of Vehicles, 1970, pp. 6—11; York & Philips, 1996, p. 144. ↩

-

To read up on the history of STC, refer to the two-volume work, York & Philips (1996) and York, Davis & Osborne (2009). ↩

-

York & Philips, 1996, vol. 1, pp. 46, 143; 丁莉英, 林明芳 & 陈金姿 [Ding, L. Y., Lin, M. F., & Chen, J. Z]. (1971). 《东南亚华人史调查报告: 新加坡华人巴士交通行业》 [Survey on the history of Singapore Chinese trades: The Singapore Chinese bus transport] (p. 71). 新加坡: 南洋大学. (Call no.: Chinese RCLOS 388.322095957 NAN); York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, p. 23. ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, p. 44. ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, p. 47. ↩

-

Old buses are main cause of poor service. (1973, March 16). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, pp. 47–51. ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, pp. 53–56, 82. ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of Communications (1974). Management and operations of Singapore Bus Service Ltd: Report of Government Team of Officials (p. 27). Singapore: Printed by Singapore National Printers. (Call no.: RSING 388.322 MAN) ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, p. 81; Ng, 2002, pp. 24–25; Looi, T.S., & Chi, C.C. (2016). An evolving public transport eco-system. In T.F. Fwa (Ed), 50 years of transportation in Singapore: Achievements and challenges (p. 83). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 388.095957 FIF) ↩

-

Sharp, 2005, p. 49; Singapore. Ministry of Communications, 1974, pp. 11, 18, 20. ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, p. 83; Sharp, 2005, p. 50. ↩

-

York, Davis & Osborne, 2009, pp. 82–83, 106. ↩