The Stories They Could Tell

Old photographs and documents can reveal new things about our history, as Yu-Mei Balasingamchow discovered when she sieved through the National Archives’ war collections.

Japanese soldiers standing victoriously on tanks bearing the Hinomaru flag and rolling down St Andrew’s Road in front of the Supreme Court and Municipal Building, 1942. All rights reserved, Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Board, Singapore.

Japanese soldiers standing victoriously on tanks bearing the Hinomaru flag and rolling down St Andrew’s Road in front of the Supreme Court and Municipal Building, 1942. All rights reserved, Lim Shao Bin Collection, National Library Board, Singapore.One aspect of growing up in Singapore is that the more you encounter the Japanese Occupation through lessons in school and as ham-handed narratives on television, the more unreal it becomes.

No one doubts the veracity of the Occupation period as historical fact, but the events that took place over seven decades ago can seem emotionally distant. While the stories recounted by my late grandmother1 and in oral history recordings from the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) are empirically true, to me − and to many others, I suspect − they seem locked up in a past that seems far removed from our lives in the present century.

So when I was engaged by NAS in 2016 as curatorial consultant for an exhibition on the Occupation, I thought I’d be operating in familiar, perhaps even predictable, territory. Even so, I found that taking a closer look at archival materials can sometimes yield surprising or intriguing results – even the odd flash of terror.

A Jolt of Reality

I remember the precise moment when the Occupation became real in a visceral and unexpected way. Together with Fiona Tan, an assistant archivist at NAS, I was looking at photographs that Lim Shao Bin, a collector of wartime memorabilia, had recently donated to the National Library. Taken by a Japanese source, the photographs captured scenes of the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and the imperial war in Asia, and were distributed as propaganda to celebrate Japanese military victories.

One photograph in this collection stopped me in my tracks. It showed Japanese soldiers standing victoriously on tanks bearing the Hinomaru flag and rolling down St Andrew’s Road in front of the Supreme Court and Municipal Building2 (later renamed City Hall, which together with Supreme Court is today the National Gallery Singapore).

The photograph is black and white, and the soldiers’ faces aren’t clearly visible – but the architecture is unmistakable. You’ve seen the same buildings in countless photographs of National Day celebrations, or as a backdrop for wedding and graduation photos and, more recently, the annual Formula One race. If you’re a history buff, you’ve also seen the same vista in photographs of the Japanese surrender ceremony in 1945, the swearing-in of Singapore’s first self-governing Legislative Assembly in 1959, and celebrations for the first Malaysia Day in 1963.

I always feel a sense of unease when I look at this photo. The iconic dome of the Supreme Court and the Corinthian columns of City Hall look much as they do today – but what are the soldiers and tanks doing there? Then, reality sinks in. A perceptible shiver runs down my spine as I think about the moment the image was taken: the sounds of Japanese troops entering Singapore, the harsh racket of tank treads on the road, the aggressive stomp of booted feet.

The photograph elicits a reaction – at least for me – because the architecture in the background is still so recognisable. There are precious few photographs of Singapore during the Occupation period, and many of them were taken in unnamed streets and places, their locations impossible to pinpoint. So when I stumble across an image that matches the present-day view of Singapore, it can provide a jolt of reality, more convincing than what statistics and historical documents could ever achieve. It is also a reminder that we should not neglect the changing emotive possibilities of an image over time and history.

Piecing the Details

Historical documents tell their own stories too, although one challenge is that they may have been deposited in the NAS without their complete context. One of the most evocative wartime collections at NAS is from David Ernest Srinivasagam Chelliah who, in 1990, donated 82 personal items relating to the war and Occupation.

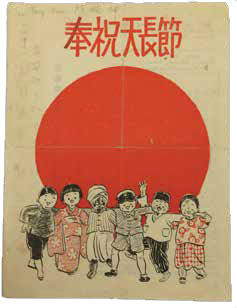

A propaganda flyer distributed in Singapore celebrating the Tencho setsu (birthday of the Meiji emperor). David Chelliah Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A propaganda flyer distributed in Singapore celebrating the Tencho setsu (birthday of the Meiji emperor). David Chelliah Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The collection is almost scrapbooklike in its diversity and messiness: a motley assortment of Japanese-language school materials, newspaper clippings, work passes and badges, mundane circulars and booklets. The items are all the more intriguing because Chelliah did not leave an oral history interview, diary or formal account of his life during the Occupation.

This is what we’ve been able to piece together from the objects: In 1941, Chelliah, at age 15, was a member of the wartime Medical Auxiliary Services (civilian volunteers who provided first aid). During the Occupation, he learned Japanese and was employed at the Japanese broadcasting department in Cathay Building. From his salary envelopes, we know that his pay was raised from 3,800 yen in 1943 to 13,000 yen, reflecting the runaway inflation of the time. His list of broadcasting department colleagues provides a glimpse of its multiracial and multilingual profile (including Thai and Vietnamese names).

David Chelliah’s student pass at a Japanese-language school and his salary envelopes when he worked at the Japanese broadcasting department in Cathay Building. David Chelliah Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

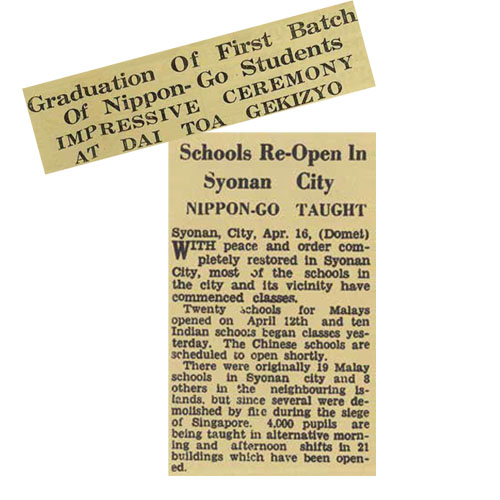

David Chelliah’s student pass at a Japanese-language school and his salary envelopes when he worked at the Japanese broadcasting department in Cathay Building. David Chelliah Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The messiest pile we had to sort out was English newspaper clippings. Some clearly recorded landmark historical moments, but also tucked away in the stash were longish newspaper articles about the Japanese language institute Syonan Nippon Gakuen. The articles were mainly mundane reports – reproduced speeches by a military representative and the head of the school, Professor Kotaro Jimbo (sometimes spelled Zimbo), repeating imperial propaganda about the need to “master Nippon-Go” (the Japanese language) and the self-styled superiority of the “Nippon Race”, and about Japanese history and culture.3 Interestingly, Jimbo was a prominent poet who, like other intellectuals in Japan, threw his support behind the imperial state’s Nipponisation project.4

Newspaper articles from the Japanese wartime newspaper Syonan Shimbun on Singapore students studying Japanese. The article praises the inaugural batch of students graduating from the Japanese-language institute Syonan Nippon Gakuen. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Newspaper articles from the Japanese wartime newspaper Syonan Shimbun on Singapore students studying Japanese. The article praises the inaugural batch of students graduating from the Japanese-language institute Syonan Nippon Gakuen. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.It was only when we scrutinised the list of graduates – there were several hundred names – that we learned two things. Chelliah had been in the second and final batch of graduates in October 1942, which perhaps explained why he had saved the articles about the first batch; he might have been trying to learn about the school before he enrolled. Also, the student profile of the language school ran the gamut of the Singapore civilian population at the time, with Chinese, Eurasian, Indian and Malay names. Whatever happened to them afterwards, here was some mention of what they were doing in the first year of the Occupation.

The fragmentary nature of Chelliah’s collection – and indeed, of many personal items that now reside with NAS – means this is all we can muster: fleeting glimpses of the little things people did for a few days, weeks or months, a snapshot of activity that may or may not have significantly changed their lives, but when put into the right context, can give us a clue to understand something of that period.

Imagine how it must have felt to be one of 250 students (out of 2,500 applicants) at Syonan Nippon Gakuen, sitting in a multiracial class of people who, until half a year ago, had only known British colonial rule. Imagine them desperately wrapping their tongues around new sounds and phrases that Professor Jimbo and his colleagues scribbled on the blackboard, wondering if they needed to know this language only for a short time – or if their new rulers were here to stay.5

After the Event, Before History

While personal collections can be fascinating, the mainstay of any national archive, including NAS, are usually government records – not usually the most inspiring materials to work with. In the course of our research, we reviewed numerous files from the British Military Administration (BMA), which took over the running of Malaya and Singapore after the Japanese surrendered on 5 September 1945. The files at NAS contain only documents that the colonial government left behind after Singapore became independent (other files are held at the National Archives in the UK), and thus yield an incomplete and subjective narrative of Singapore during the period of BMA rule.

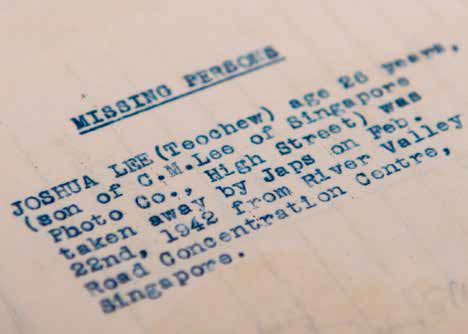

Even so, there were rediscoveries to be made. Flipping through the dog-eared files of seemingly miscellaneous documents, some of them as fragile as onion-skin paper, we noticed a pattern emerge in typewritten sheets that bore the names and personal details of missing persons: they were all Chinese and last seen in February 1942 at “concentration centres” in River Valley Road or Arab Street.6

However little Singaporeans might know about the Occupation, they would have heard about the Sook Ching, the Chinese term now used for the military operation that took place at the start of the Occupation – specifically in the last two weeks of February 1942. Chinese men (and some women and children) were detained and arbitrarily screened, and thousands were taken away to be massacred. Some of the known screening centres were at Arab Street, Hong Lim Park, Tanjong Pagar Police Station, Jalan Besar, Telok Kurau School and River Valley Road.

Looking at the missing person reports, it’s easy to dismiss them as just pieces of paper from another place and time. Then I think about the family members who thronged the BMA offices at the Municipal Building – the same building described in the photograph earlier – to report their missing husbands, sons, fathers, brothers, uncles, nephews and neighbours, who spent three-and-a-half years not knowing the fate of their loved ones, and who faced the British man with the typewriter. I think about the BMA official, typing one report after another, day after day, perhaps feeling harried or bored or simply overwhelmed by his work.

Amid the deluge of requests for help that the BMA received, did someone at the BMA suddenly realise that an awful lot of missing persons were Chinese men who had not been seen since February 1942? At what point did the missing person reports, the ones I had held in my hands at NAS, start to sound eerily the same to officials working at the BMA?

A missing person report on one Joshua Lee that was filed with the British Military Administration in Singapore in the days following the end of the Japanese Occupation. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A missing person report on one Joshua Lee that was filed with the British Military Administration in Singapore in the days following the end of the Japanese Occupation. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The only clue in the BMA files is a copy of a letter from BMA official Mervyn Sheppard to the BMA Adviser for Chinese Affairs, Hugh Pagden. Sheppard wrote, “The whole question of the murder of hundreds of innocent Chinese soon after the fall of Singapore should, I think, be the subject of early enquiry.”7 Indeed, within the first month of the British return, The Straits Times had published several letters from Chinese members of the public, urging the BMA to investigate the missing Chinese persons.8

The patchy documents in the BMA files, however, offer a different angle to the now well-worn narrative of the Sook Ching. They transport us back to a time in late 1945 when the full scale of the atrocities was not yet understood and assembled into a coherent historical event. Both the BMA and civilian Chinese population were still trying to figure out what had happened in those anguished weeks from three-and-a-half years ago. There were only missing people, and no immediate answers.

Soon, the events would become known as the “Chinese massacres”, and decades later, as the Sook Ching. Today, we have documented knowledge that allows us to regard these scraps of paper with greater immediacy. We know how the story unfolds and how it ends – and what a harrowing story it was.9 I think these plain slips of bureaucracy mean more now, not less, because we can understand, even more fully than their creators, what they convey beyond the knowledge that was available at the time.

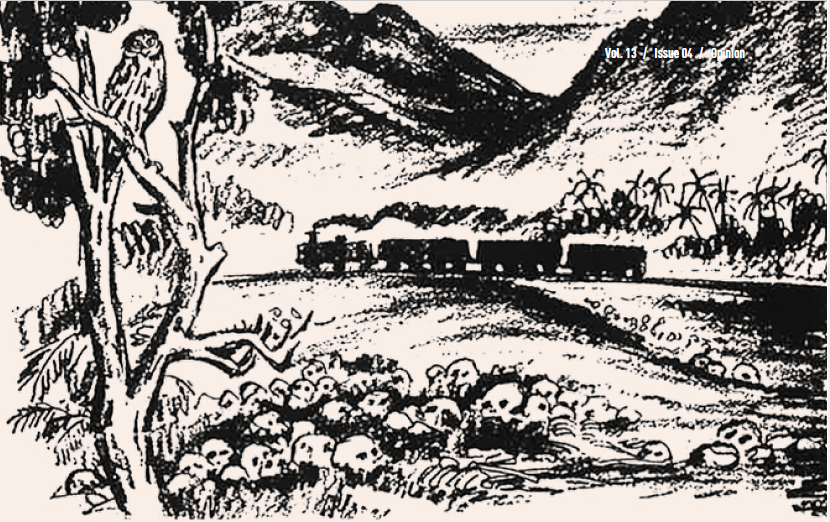

The Sook Ching massacre that took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942 saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. This sketch is from Chop Suey, a four-volume book of illustrations by the artist Liu Kang on the atrocities committed by the Japanese military. All rights reserved, Liu K. (1946). Chop Suey (Vol.III). Singapore: Eastern Art Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02901747H)

The Sook Ching massacre that took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942 saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. This sketch is from Chop Suey, a four-volume book of illustrations by the artist Liu Kang on the atrocities committed by the Japanese military. All rights reserved, Liu K. (1946). Chop Suey (Vol.III). Singapore: Eastern Art Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02901747H)For any historical event, meanings change as time passes. To me, archives are closed, inert boxes filled with things to be sorted and stored – yet they contain the possibility of re-evaluation and rediscovery. Every time I go ferreting in the archives, I remind myself that while we are used to thinking of artefacts and documents as bearers of literal meaning, they can also be read at other levels, and for other meanings. They bear revisiting, even when on the surface nothing has changed.

The objects and materials described in this essay can be seen in the permanent exhibition, “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and Its Legacies”, at the Former Ford Factory and on microfilm at NAS’s Archives Reading Room (temporarily located at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library on Level 11 of the National Library Building).

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

NOTES

-

Balasingamchow, Y.M. (2016, Jul–Sep). My grandmother’s story. BiblioAsia, 12 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

The image is reproduced as a large wall graphic in the permanent exhibition “Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and Its Legacies” at the Former Ford Factory. It is several metres in width, and is found at the start of the gallery on the history of the Occupation. ↩

-

Graduation of first batch of Nippon-go students (1942, August 4). The Syonan Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Matsuoka, M. (2017). Media and cultural policy and Japanese language education in Japanese-occupied Singapore, 1942–1945 (pp. 83–102). In K. Hashimoto (ed.), Japanese language and soft power in Asia. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Syonan Nippon Gakuen has fulfilled its mission – principal’s reflections. (1942, October 30), The Syonan Times, p. 2; Graduates of Nippon Gakuen.(1942, October 31). The Syonan Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

NAS accession number 24/45 (4, 12, 21, 22 and 23). ↩

-

Copy of letter from Sd. M.C.ff. Sheepard [sic] to S/Ldr H.T. Pagden, 6 November 1945, NAS accession number 24/45(26a). Sheppard later rejoined the Malayan Civil Service (where he had been employed before the war) and, from 1958 to 1963, served as the founding director of the National Archives in Malaysia. He was also concurrently the first director of the National Museum of Malaysia. See Hack, K., & Blackburn, K. (2012). War memory and the making of modern Malaysia and Singapore (p. 217). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 940.53595 BLA-[WAR]) ↩

-

See for instance Fang, W.L. (1945, September 22). Missing Chinese appeal to military administration. The Straits Times, p. 2; and Wong, T.F. (1945, September 26). Yamashita’s act. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For historical accounts of the Sook Ching operation and how it became memorialised, see Lee, G. B. (2005). The Syonan years: Singapore under Japanese Rule, 1942–1945. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]) and Blackburn & Hack, 2012. ↩