An Ode to Two Women

Acclaimed poet and playwright Robert Yeo pays tribute to his daughter and a noted author in chapter two of his work-in-progress sequel to his memoir Routes.

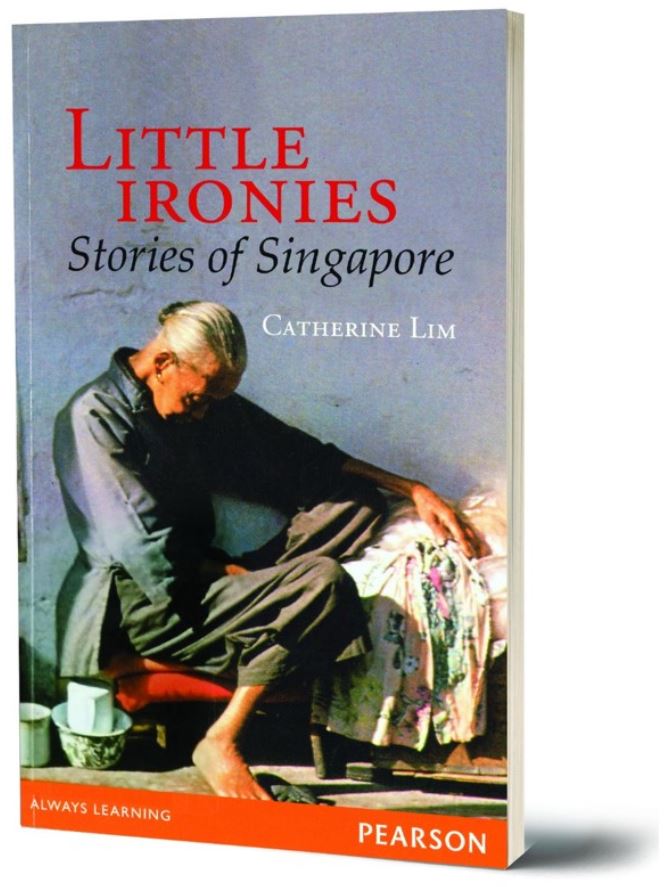

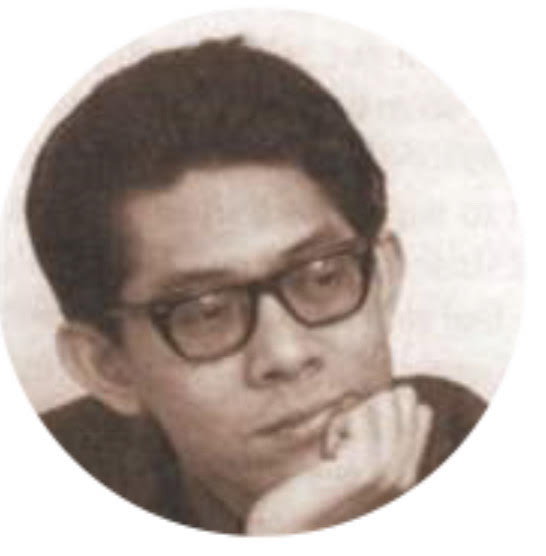

(Middle) Robert Yeo in a pensive pose in 1966 when he was 26 years old. Courtesy of Robert Yeo.

(Right) Catherine Lim is regarded as the doyenne of Singaporean writers. Little Ironies: Stories of Singapore (1978), which is her first published book, earned her many accolades and is an all-time bestseller. Courtesy of Marshall Cavendish Editions.

My wife Esther reminded me that it was a miracle, considering what she did in Bali in June 1975. It was our first visit to the famed island and we chose to stay in Kuta. It was all sea, sand, waves and coconut trees. We even asked a boy to climb a tree to pluck coconuts for us to drink the water. There were no buildings on the beach.

The surfing waves were not suitable for swimming but we found ways to enjoy ourselves. We allowed the waves to toss and roll us onto the sand, taking repeated tumbles, sometimes all shook-up and even painfully so. We did this twice a day over three to four days.

We loved one particular item and bought it, a beautifully carved full-length 1½-foot sculpture of the Hindu goddess Sita, made from tree bark and which weighed 10 pounds. On the way home, I was feverish and Esther had to carry the piece back to Singapore all by herself. Back home, she too became feverish a few days later and discovered she was pregnant. Wow, we thought, how lucky she was, what with all the tumbles she took in Kuta and carrying a heavy piece of sculpture, that nothing happened to her baby, our baby!

I became a father on 15 February 1976. My daughter Sha Min was born in Kandang Kerbau Hospital. There were two facts remarkable about her birth: the first that it was long and difficult, needing 20 hours of labour; and second, at the time of her birth, the government public maternity hospital held the record of delivering the most number of babies per year in the world. This record, which the hospital held from 1966 to 1976, may have later contributed to the government’s fear of overpopulation and prompted it to regulate birth as an official policy.

In the midst of her long labour when her pain became unbearable, my wife asked a nurse about epidural intervention and was confronted by the cold question from one of the nurses, “Who told you about epidural?” So the birth was natural, but the experience certainly did not make her feel she would like another baby in the near future.

Sha Min (善敏) means kind and alert. Esther was adamant that she did not want her first daughter to have a name that has a Nonya syllable, such as Gek, Geok, Poh, Neo, as my mother had lined up traditional names for her first grand-daughter. I agreed and so we consulted a Chinese almanac that took into account time, date of birth and gender, a process managed by Esther’s late father, who is Cantonese.

What was it like to be a father for the first time and a daughter as the firstborn? 1976 was the year of the dragon and a traditional Chinese father would expect a boy who could continue to bear the Yeo surname.

I wrote a poem about it.

For My Daughter Sha Min

Hushed, we hovered between rabbit and dragon,

Between a whitish squeak and flaming breath.

When you declined to be a rabbit, like

Your father, the hush dissolved,

and I was pleased

Knowing how auspicious the dragon is.

I was prepared to wait, but it’s lovely

To be scorched so soon, as long

as you will

Promise not to burn our house to

the ground

Girl or boy, your sex didn’t really matter.

I’m not the traditional Chinese father

Who needs a son to continue his line

And swell his clan. My brothers may

line up,

And my clan of two-and-a-half million,

Though small, is big enough for me,

for us.

I don’t know whether small is beautiful,

But since we have no choice, let’s

make it so.

Sha Min, sweetheart, you know

this prayer

I offer you is really not a prayer as

You are born in a good year in a good place,

The prospect of water-rationing

notwithstanding…

Say rather that I’m offering you a hope,

One of the many hopes; and so as

not to seem

Arbitrary, let there be three, yes three,

As this is the year of the three-

clawed dragon.

I quote the poem fully to demonstrate the disjunct between the name and the character the baby is supposed to take on. Sha Min did not turn out to be dragonish at all; in fact, she grew up to be a very agreeable and even-tempered girl.

In addition, quoting the poem entirely also shows the pains I took to write in such a way that avoided the obvious influence of the great poem by W.B. Yeats, A Prayer for My Daughter. Hopefully, the Chinese mythological references will differentiate my poem from his.

In the process of collecting and editing short stories for an anthology of Singaporean writing from 1940 to 1977, I came across the stories of Catherine Lim. Subsequently I met her.

Catherine was a young teacher of English Language and English Literature in a junior college. She had lively, sparkling eyes, and was very fair and slim in a way that fitted the cheongsam she wore. I told her I liked the few stories of hers that I had read in magazines and newspapers, and asked if she could show me more.

A few days later, a few stories arrived and I was struck first by their appearance. Typed and marked up with pencilled or inked corrections, the A4-sized papers were crumpled, yellowed and dog-eared, evidence that they had been kept in drawers, read, moved-about and all but forgotten.

Secondly, I thought the stories were excellent as they had a sharp, satirical eye for human foibles and detail, showing a society in the throes of transiting from tradition to modernity. I thought, “How exciting it would be if she had enough for a single volume of just her stories”, and asked her to send more.

I had read about seven to eight stories, but they were not enough to make up a book. She did send more, altogether 17 stories. I forwarded them to John Watson, the genial, tall and bearded Englishman who was the General Manager of Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd, which had an office in Jalan Pemimpin.

Together with Leon Comber, based in Hong Kong, John had just started to publish titles in the Writing in Asia Series and he was pleased with Catherine’s stories. Consistent with editorial practice, he sent her stories to the eminent English author, Austin Coates, who lived in the British colony; Coates was the author, among many books, of one of the best biographies of Jose Rizal, the Filipino doctor, revolutionary and national hero, and he gave her stories a ringing preview. John showed me what Coates wrote:

“They are riveting; there is no other word for them. In their Singapore Chinese context they rank with the best of Guy de Maupassant and the Alphonse Daudet. Each story has the same sureness of observation, clarity in the presentation of character, and finely judged economy both of words and emotion…. Her knowledge of Chinese ways of living and habits of thought is masterly. It may sound absurd to say this, but so few people are able, as she is, to draw back and look at it objectively. She exposes men and women with a mixture of complacent ruthlessness and compassion.”

Catherine Lim’s stories were published in a book entitled Little Ironies in 1978 to much acclaim. It marked the beginning of her remarkable career in English writing in Singapore.

Robert Yeo, born 1940, is best known for his poems and plays published in The Singapore Trilogy (plays) and The Best of Robert Yeo (poems). He has also written in other genres, including essays, libretto for opera and edited anthologies of Singapore short stories. His most recent work is the play The Eye of History (2016). Volume 1 of his memoir, Routes: A Singaporean Memoir 1940–75, was published in 2011.

Robert Yeo, born 1940, is best known for his poems and plays published in The Singapore Trilogy (plays) and The Best of Robert Yeo (poems). He has also written in other genres, including essays, libretto for opera and edited anthologies of Singapore short stories. His most recent work is the play The Eye of History (2016). Volume 1 of his memoir, Routes: A Singaporean Memoir 1940–75, was published in 2011.