Bridging History: Passageways Across Water

Lim Tin Seng traces the history of nine iconic bridges spanning the Singapore River that have ties to the colonial period.

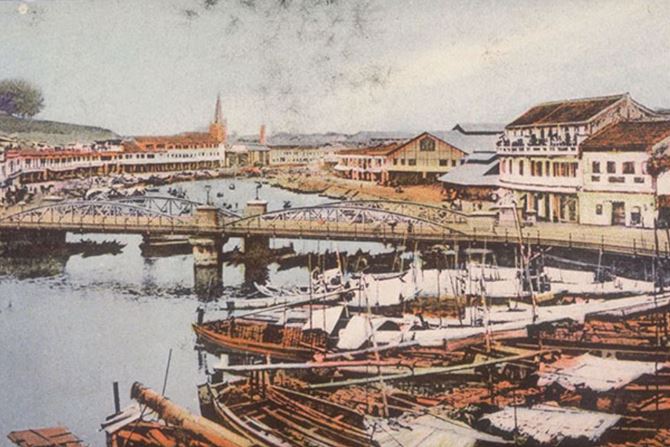

The bridges erected over the Singapore River during the colonial period are more than mere structures providing safe passageway across this historic body of water. They were hailed as marvels of engineering – given the technology and building materials available at the time. More importantly, by promising conveyance to an endless stream of human life and cargo, these bridges also came to symbolise the lifeblood of transportation, commerce and social interaction in pre-independent Singapore.

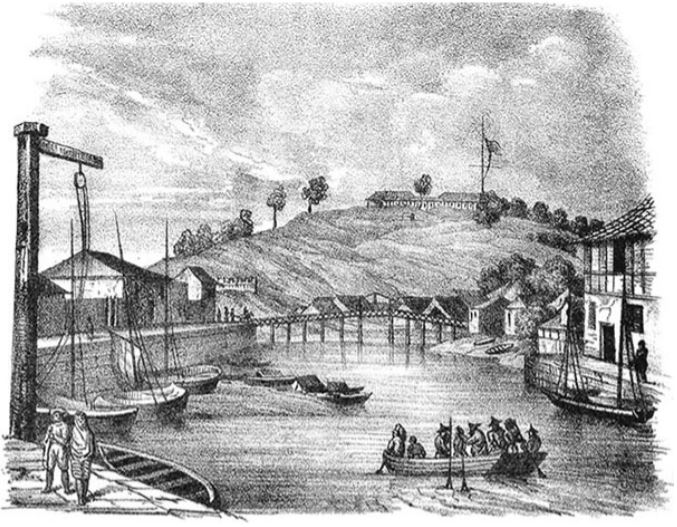

Despite such lofty associations, many of these colonial bridges started out as humble wooden structures. One of the earliest that spanned the Singapore River dates back to 1823. This rickety bridge made of wood was known as Presentment Bridge, and stood at the site where Elgin Bridge is found today.1

Stronger materials such as iron, steel and reinforced concrete, as well as more sophisticated structural bridge designs like the steel truss arch, the tied-arch and the truss girder, were not adopted until after the second half of the 19th century.2 The introduction of new materials, designs and technology to Singapore was the legacy of the colonial government, who called upon foreign architects, civil engineers and builders to lend their expertise to bridge building projects on the island.

From the final decades of the 19th century until the 1950s, Singapore would witness the construction of modern iron bridges, such as the first Elgin Bridge, Ord Bridge, Read Bridge, Cavenagh Bridge and the third Coleman Bridge, as well as stronger steel or reinforced concrete bridges like Anderson Bridge, the second Elgin Bridge and the second Read Bridge.

1. Anderson Bridge

Anderson Bridge, which connects Empress Place to Collyer Quay, is named after John Anderson, Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner for the Federated Malay States (1904–11). In 1901, a proposal was made to replace Cavenagh Bridge – which had been used since 1869 – with Anderson Bridge.

Cavenagh Bridge could no longer support the growing vehicular and pedestrian traffic that came with the rapid development of Singapore because its low height allowance prevented vessels from passing unencumbered beneath at high tide. After Anderson Bridge was built in 1910, Cavenagh Bridge was, fortunately, spared the wrecking ball and turned into a pedestrian bridge.

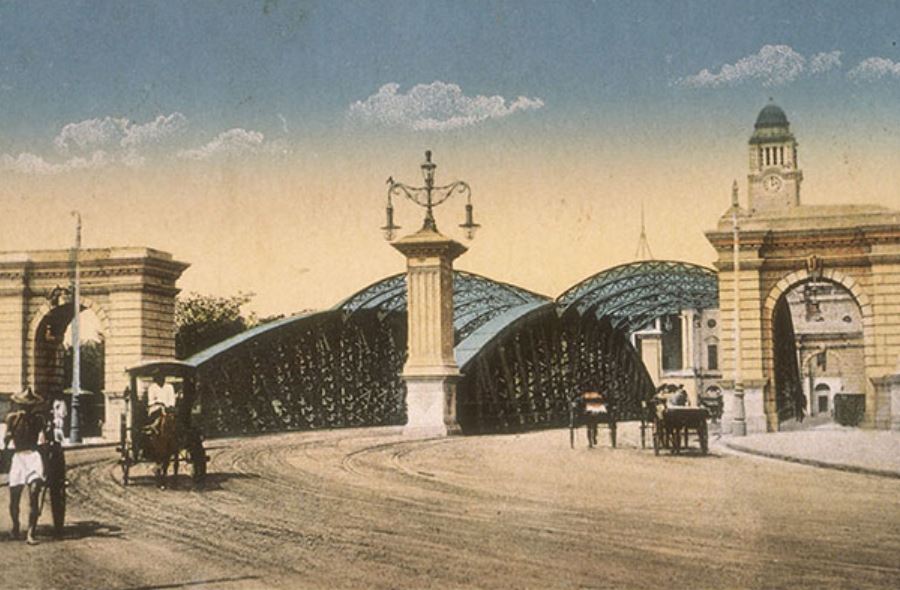

Anderson Bridge was designed by Municipal Engineer Robert Peirce and his assistant D.M. Martia. With a length of about 230 ft (70 m), the bridge has an elaborate steel truss structure comprising three steel arches spanning the length of its deck framed by a towering column at each end. Each column bears a plaque made of red granite imported from Egypt. The bridge also has two pedestrian footpaths, one on each side, and rusticated archways flanking each footpath, making a total of four archways.

The bridge was constructed by Howarth Erskine Ltd and the abutments by the Westminster Construction Company Ltd. The steelwork was fabricated in Britain, while other components such as the railings, castings, rainwater channels, gully frames and covers were produced locally at the municipal workshops on River Valley Road.

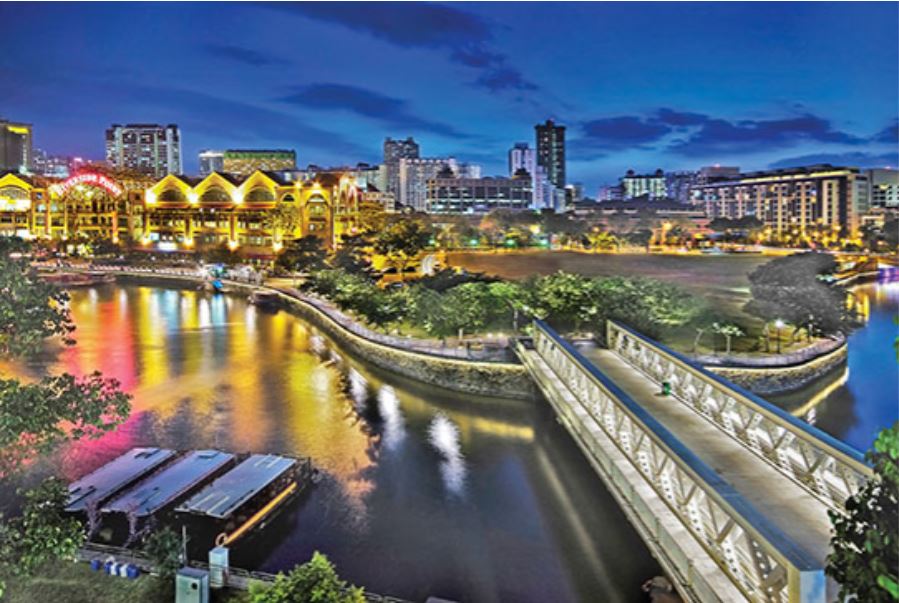

In 1987, the bridge was refurbished as part of the Singapore River masterplan and subsequently earmarked for conservation by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in 2008. Today, the bridge is used by both vehicles and pedestrians. Every year since 2008, the bridge is bathed by the glare of floodlights after darkness falls as one of the landmarks in the serpentine Formula One Singapore Grand Prix.

2. Cavenagh Bridge

Cavenagh Bridge is named after William Orfeur Cavenagh, the last Governor of the Straits Settlements under British India control (1859–67). Completed in 1869, it is the oldest bridge in Singapore that still exists in its original form.3 The bridge was designed by George Chancellor Collyer, Chief Engineer of the Straits Settlements, and Rowland Mason Ordish, a civil engineer based in London.

Ordish was responsible for the design of several notable projects in London, including Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace (1851) and the dome-shaped roof of Albert Hall (1871). He was also a prolific bridge builder, having designed the Franz-Josef Bridge in Prague (1868) and the Albert Bridge in London (1873). In 1858, Ordish patented a bridge construction method called Ordish’s straight-chain suspension bridge, which comprised a rigid girder suspended by inclined straight chains instead of hanging chains. This cutting-edge technology was adopted for Cavenagh Bridge, giving the bridge the design we see today.4

The bridge was constructed using iron to ensure that it could withstand the high tensile forces of the cables. The iron components were fabricated in Glasgow, Scotland, by P & W MacLellan, the same firm that made the cast iron for Telok Ayer Market. The components were later shipped to Singapore and assembled by Indian convict labour.

Although Cavenagh Bridge was built too low for vessels to pass beneath it during high tide, it served the local populace and business community well. In fact, it was used by both vehicles and people who traversed between the business district of Commercial Square (today’s Raffles Place) at the south bank of Singapore River and the administrative district in the north. By the time Anderson Bridge was opened in 1910, Cavenagh Bridge had served its purpose and was converted into a pedestrians-only footbridge.

Around 30 years ago, Cavenagh Bridge underwent a five-month refurbishment at a cost $1.2 million to preserve and strengthen its structure. It reopened on 3 July 1987.

3. Elgin Bridge

As mentioned earlier, Presentment Bridge was one of the first bridges erected by the colonial government over the Singapore River. Built in 1823 by Philip Jackson, the Assistant Engineer and Surveyor of Public Lands, to link the northern and southern banks of the river, the wooden bridge sat on timber piles. It was 240 ft (73 m) long and 18 ft (5.5 m) wide, and had an arch in the middle that could be drawn to allow vessels to pass beneath.5

After numerous repairs undertaken between 1827 and 1842, Presentment Bridge was demolished and replaced by another wooden bridge in 1844 called Thomson Bridge. It was named after its architect John Turnbull Thomson, who was then Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements. Like its predecessor, the bridge also underwent several rounds of repairs before it was dismantled and replaced with Elgin Bridge in 1862.

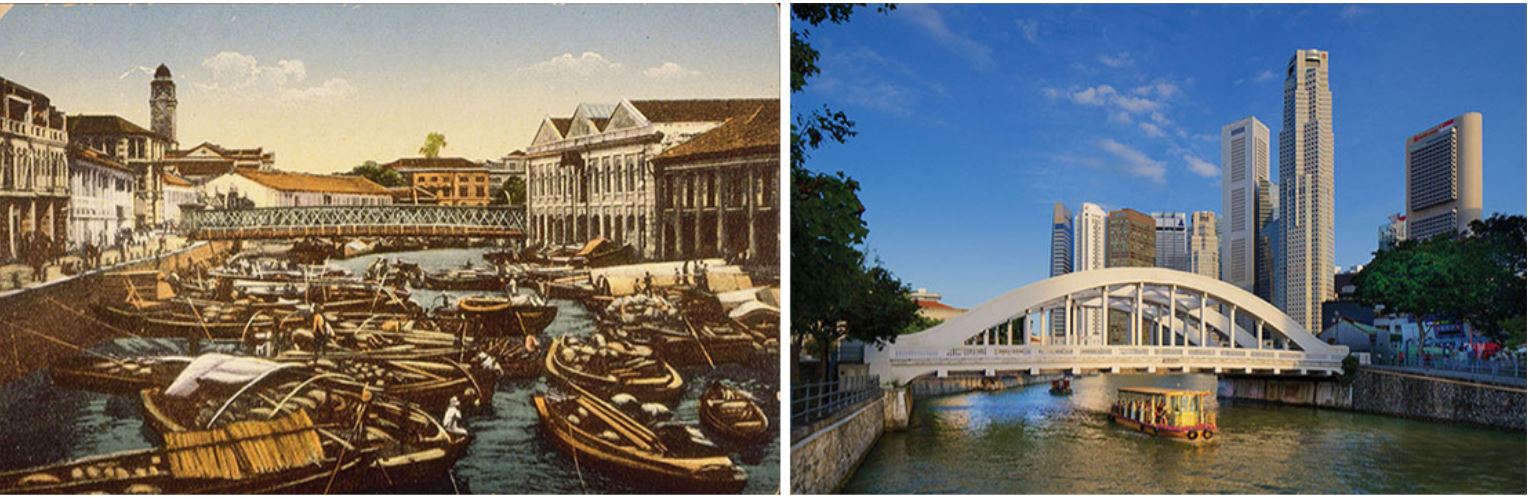

The bridge that we see today is, in fact, not the first but the second Elgin Bridge. It is named after the 8th Earl of Elgin, Lord James Bruce, also the Governor General of India (1862–63), and connects North Bridge Road with South Bridge Road. The first Elgin Bridge was built in 1862 by engineer George Lyon to replace the aforementioned Thomson Bridge.

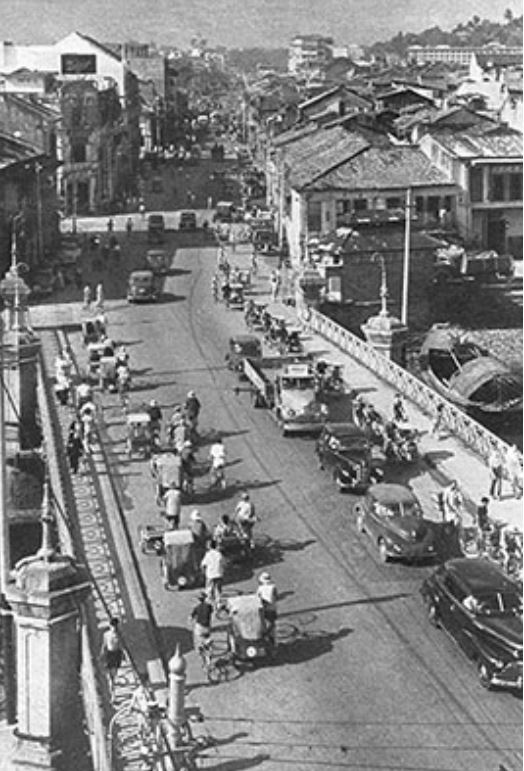

When completed, the first Elgin Bridge, like the bridges before it, served as an important transportation conduit between the north and south banks of the Singapore River. In 1886, the bridge was widened and strengthened to accommodate growing traffic as well as a tramway line. By the 1920s, traffic using the bridge had become so heavy that a decision was made in 1925 to replace it with an even wider one that could accommodate two 25-ft (7.5 m) carriageways and a “five-foot way” (as pavements or walkways were referred to in the colonial period) on each side.

The new structure, which would become the Elgin Bridge we see today, was completed in 1929. It was designed by Municipal Bridge Engineer T.C. Hood and features three elegant arches supported by slender hanging columns. The concrete-encased steel framework was fabricated in Glasgow and assembled locally. On both ends of the bridge are cast-iron lamp posts and roundels of the Singapura lion designed by Italian sculptor Cavalieri Rodolfo Nolli. These embellishments were salvaged from the first Elgin Bridge.

(Right) The second and current Elgin Bridge, 2016. The bridge stands on the site of one of the first bridges built across the Singapore River called Presentment Bridge. Elgin Bridge is named after the 8th Earl of Elgin, Lord James Bruce, also the Governor-General of India (1862–63). Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

In 1989, Elgin Bridge was repaired and strengthened as part of the masterplan to liven up the Singapore River. Two pedestrian underpasses were added in 1992. On 3 December 2009, the bridge was given conservation status by the URA.

4. Coleman Bridge

Coleman Bridge, which links Hill Street and New Bridge Road, was named after its brainchild, George D. Coleman, Singapore’s first Government Superintendent of Public Works (1833–44). History, however, records four Coleman bridges in all.

The first was conceived as early as 1833 as an iron suspension bridge to provide a second passageway – in addition to Presentment Bridge – across the Singapore River. But when the bridge was erected in 1840, the builders again used wood instead of iron. The 20-ft-wide (6 m) bridge was made of wood harvested from the damar laut tree, a material considered to be “of the very best description of timber”.6

Although this first Coleman Bridge was deemed a “perfect [work] of a permanent and substantial order”, it soon succumbed to wear and tear.7 In 1864, it was torn down and replaced with the second Coleman Bridge. Completed in 1865, the second bridge was designed to be “stronger and more serviceable” than the first.

However, once again, due to budget constraints, a wooden rather than steel structure was erected, much to the chagrin of the public.8 The bridge was also poorly constructed, and on the eve of its opening, it was reported that several parts of the bridge were already “improperly fastened” and its piles “eaten by sea worms”.9 The bridge was closed in 1883 and replaced three years later in 1886 by the third Coleman Bridge.

To rectify the shortcomings of its predecessors, the third reincarnation of the bridge was constructed using iron. The entire length of the deck was held up by a continuous girder with a curved lower flange that spanned 76 ft (23 m) at the centre and 38 ft (11.5 m) at both ends. It featured a pedestrian walkway on each side as well as three lanes to accommodate the ever increasing traffic between the northern and southern parts of town. The bridge was adorned with ornamental cast-iron lamp posts and intricate iron balustrades bearing Victorian motifs.

The bridge was built to last, and so it did for a full 100 years before it was replaced by the fourth and current Coleman Bridge. Constructed in phases between 1986 and 1990 as part of the New Bridge Road Widening Scheme, the new twin-bridge hosts a four-lane carriageway on each of its decks as well as pavements and underpasses for pedestrians. To preserve the history and heritage of the bridge, elements from the third Coleman Bridge, including the arched support, cast-iron lamp posts and iron balustrades, were retained.

5. Read Bridge

Read Bridge was built to link Clarke Quay and Hong Lim Quay, and the one standing today is not the original but the second Read Bridge. Before the first Read Bridge was constructed in 1889, Merchant Bridge occupied the same location – named after the merchant warehouses that once lined both ends of the bridge. The wooden structure, which was completed in 1869, was also referred to as Tan Tock Seng Bridge, after the prominent Chinese merchant and philanthropist, Tan Tock Seng, who owned several shophouses nearby. In 1886, the municipality decided to replace Merchant Bridge with the first Read Bridge after the former was found to be “in a shaky condition”.10

The first Read Bridge was an iron girder bridge, with two 77-ft (23 m) spans and a concrete pier in the middle to support the structure. Construction of the bridge began in 1887, and its first cylinder was laid by William Henry Macleod Read, the Scottish merchant and public figure after whom the bridge was named. Although the bridge served the mercantile community well, it turned out to be too low for heavily laden twakow (lighter boats) to pass under during high tide, and had to be replaced eventually.

Completed in 1931, the second Read Bridge was a steel box girder bridge designed by Municipal Engineer K.G.M. Fraser. It was a utilitarian structure simply adorned with only four ornamental street lamps.11 The initial design, however, by Municipal Bridge Engineer T.C. Hood, was envisaged as a tied-arch structure with a towering 120-ft-high (36.5 m) arch similar to that of the current Elgin Bridge. But due to insufficient funds, this design was abandoned.

The steelwork of the second Read Bridge was manufactured by the British firm Motherwell Bridge and Engineering, but as the material became exposed to the harsh tropical climate, it began to corrode not long after its completion. By the end of the decade, the bridge was reported to have suffered “exceptionally heavy corrosion, despite being designed with particular care”.12 In 1991, the bridge underwent major repairs as part of the Singapore River clean-up and was converted into a pedestrian bridge.

In the early days, Read Bridge was variously known as Malacca Bridge as it was located close to Kampong Melaka, and also Green Bridge due to the colour of its original paintwork. At the time, the area around the bridge was also a hub for the Teochew community, with Teochew labourers gathering on the bridge after work in the evenings to listen to traditional storytellers. In 2008, the bridge was conserved by the URA.

6. Ord Bridge

Ord Bridge – which links Clarke Quay and River Valley Road – was constructed in 1886 and named after Harry St George Ord, the first Governor of the Straits Settlements (1867–73). It replaced a footbridge known as Ordnance Bridge, which was built in 1865. The latter was so named because an arsenal and commissariat store was located nearby. Ordnance Bridge was also called ABC Bridge, after ABC Road, which later became Ord Road (now expunged).

Structurally, Ord Bridge is an iron bridge with distinctive X-shape girders. The 135-ft-long (41 m) and 24-ft-wide (7 m) bridge has a structure that resembles standard-gauge railway bridges as it was modelled after similar bridges in India. However, about a month after the bridge was opened, it suffered a mishap, with the weight of the structure causing the northern abutment to slip. This problem was later traced to the way in which the piers had been laid during construction; they were found standing on “tiptoe” on a slopping bedrock rather than embedded firmly into solid foundation.13

Ord Bridge was also known as Toddy Bridge because of the many toddy (palm liquor) shops operating in the area. The bridge has since come under URA’s conservation programme.

7. Clemenceau Bridge

This bridge that spans the Singapore River today is the second Clemenceau Bridge at this site. It is named after Georges Benjamin Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister (1906–09 and 1917–20) who visited Singapore in 1920.

The first Clemenceau Bridge was built in 1940 by Fogden, Brisbane and Company Ltd. The original structure was 330 ft (100 m) long and 60 ft (18 m) wide, with a height clearance of 7 ft (2 m) for vessels to pass beneath during high tide. This bridge was designed by Municipal Bridge Engineer T.C. Hood. Although it was a simple looking structure, it is remembered as the first bridge in Singapore that used web guilders. The entire bridge was constructed using reinforced concrete to improve its resistance against corrosion, a problem that had plagued most of the bridges along the Singapore River at the time. The bridge was built as part of a road scheme that stretched from Clemenceau Avenue to Keppel Road, and replaced the Havelock stretch of Pulau Saigon Bridge. The latter was referred to in the early maps of Singapore town as Bridge No. 1.

The first Clemenceau Bridge stood for nearly 50 years before it was demolished in 1989 to make way for the Central Expressway (CTE). A new replacement bridge with the same name was then built in 1991. Today, the bridge, which has eight lanes instead of the previous four, connects the CTE’s Chin Swee Tunnel with Clemenceau Avenue.

8. Pulau Saigon Bridge

Pulau Saigon Bridge is named after a small island that once sat in the middle of the Singapore River between Clarke Quay and Roberston Quay, facing Magazine Road. Initially a mangrove marsh, the island was later home to a village called Kampong Saigon. After the island was enlarged in 1884, merchants began to use the island to store goods from Indochina. By the early 1900s, the island had become a rather busy place filled with warehouses and sago mills. There was reportedly even a municipal waste incinerator as well as a railway depot on the island.

In post-1890s maps of Singapore, Pulau Saigon Bridge is shown to be made up of two bridges, Bridge No. 1 and Bridge No. 2. Both bridges were built during the 1890s: the first linked Pulau Saigon to the northern bank of the Singapore River, leading to roads such as River Valley Road and Merbau Road, while the second bridge, on the other side of Pulau Saigon, linked the island to roads at the southern bank, such as Havelock Road and Magazine Road.

When the first Clemenceau Bridge was constructed in 1940, Bridge No. 1 was demolished. Bridge No. 2, which had a single arch similar to that of Anderson Bridge and Elgin Bridge, would remain standing until Pulau Saigon was reclaimed to join the mainland in the 1980s. The 141-ft-long (43 m) Pulau Saigon Bridge we see today was built in 1997. The five-lane bridge, which links Saiboo Street and Havelock Road, has a granite-finished pedestrian pavement on each side as well as a 197-ft-long (60 m) pedestrian underpass.

9. Kim Seng Bridge

Kim Seng Bridge is located at the stretch of the Singapore River just before it emerges from a small canal.14 It is named after Tan Kim Seng, a prominent merchant and philanthropist who donated 13,000 Straits dollars to the colonial government in 1857 for the construction of Singapore’s first reservoir and waterworks.

Predating the present bridge are two earlier constructions. The first was reportedly built in 1862 before it was replaced by the second bridge in 1890. The second bridge was depicted in early maps of Singapore as being part of Kim Seng Road, which runs from River Valley Road at the northern side of the Singapore River to Havelock Road in the south.

In 1953, the City Council decided to replace the second Kim Seng Bridge with the present bridge. A new bridge was needed to relieve traffic congestion as well as eliminate a dangerous horseshoe bend at the southern end of the bridge that had been the scene of many fatal accidents.

The new bridge was completed in 1955 and, at 85 ft (26 m) long and 66 ft (20 m) wide, it is twice the size of its predecessor. The bridge was built by Ewart and Company, which used pre-stressed concrete, a new building material, as well as special high tensile steel from Britain, thus allowing the bridge to hold a load of up to 2,700 pounds per sq ft (13,183 kg per sq m).

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

References

Barry, J. (2000). Pulau Saigon: A post-eighteenth century archaeological assemblage recovered from a former island in the Singapore River (pp. 11–13). Stamford: Rheidol Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BAR-[HIS])

Bridges to the past along the Singapore River. (1986, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. 2, pp. 690, 783). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS])

Goh, C.B. (2013). Technology and entrepôt colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940 (p. 112). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 338.064095957 GOH)

Hancock, T.H.H. (1986). Coleman’s Singapore (pp. 1–2, 66, 87). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Pelanduk Publications. (Call no.: RSING 720.924 COL.H)

National Archives of Singapore. (1913). Map of Singapore showing the principal residences and places of interests [Survey map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Ng, M.F.C. (2016). Singapore River walk (pp. 47–56). Singapore: National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 915.95704 NG-[TRA])

Samuel, D.S. (1991). Singapore’s heritage: Through places of historical interest (p. 86). Singapore: Elixir Consultancy Service. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SAM-[HIS])

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (pp. 88–89, 317, 322–324). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV-[TRA])

Singapore. Municipality. (1930). Administration report of the Singapore municipality for the year 1929 (p. F–2). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. (Microfilm no.: NL3414)

De Silva, Leo & Chandradas. (1985, September 30). Singapore River preserved. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Survey Department, Federated Malay States and Straits Settlements. (1893).

Tan, I. (2012). Bridges to our heritage: The significance of five historic bridges over Singapore River (pp. 50–52, 67–70). Retrieved from University of Edinburgh website.

Hon, S,S. (1893). Plan of Singapore Town Showing Topographical Detail and Municipal Numbers [Survey map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Tyers, R.K. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then & now (pp. 7, 11–12, 26–27, 95). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TYE-[HIS])

Wan, M.H., & Lau, J. (2009). Heritage places of Singapore (pp. 9–15). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 WAN-[HIS])

Notes

-

Cheong, C. (1992). Framework and foundation: A history of the Public Works Department (p. 50). Singapore:Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 354.5957008609 CHE) ↩

-

Tan, I. (2012). Bridges to our heritage: The significance of five historic bridges over Singapore River (pp. 50–52). Retrieved from University of Edinburgh website. ↩

-

Curl, J.S. (2016). The Oxford dictionary of architecture (p. 539). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.(Call no.: R 720.3 CUR) ↩

-

Lee, K.L. (n.d.). EIC Letters, 1, pp. 11, 17, 20, 41.(Call no.: RDLKL 959.5703 EIC) ↩

-

Lee, n.d.,1, pp. 116, 123; Lee, K. L. (n.d.). EIC Letters, 2, pp. 183, 214, 230, 246, 291. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.5703 EIC) ↩

-

Coleman St. Bridge. (1864, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press: Coleman Bridge. (1865, March 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Municipal Council: Coleman Bridge. (1865, February 25). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Town bridges: Merchant Bridge. (1886, July 1). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore River smell corrodes bridge. (1939, April 17). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ord Bridge. (1886, September 2). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Silva, L., & Chandradas. (1985, September 30). Singapore River preserved. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩