Farquhar & Raffles: The Untold Story

The founding of Singapore in 1819 and its early development have traditionally been attributed to Sir Stamford Raffles. Nadia Wright claims that his role has been exaggerated at the expense of another.

In 1830, William Farquhar (1774–1839) wrote to The Asiatic Journal explaining why he was due “at least a large share” of the credit in forming Singapore.1 Yet, it is Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) alone who is hailed as the founder of Singapore. This notion, propounded by his biographers, has been reinforced by constant repetition, official acceptance and the omnipresence of Raffles’ name in Singapore.

In contrast, Farquhar’s pivotal role in the events leading up to the founding of the British settlement in Singapore in February 1819 and during its nascent years has been vastly underrated. To add insult to injury, Farquhar has been mocked, and his character and accomplishments belittled over the years.

To understand the origins of this aberration in Singapore’s history, we must turn to the biographies of Raffles. The first, The Life of Sir Stamford Raffles, written by Demetrius Boulger in 1897, during the heyday of the British Empire, would establish the trend of glorifying Raffles and disparaging Farquhar.2

The First Biography on Raffles

Boulger portrayed Raffles as a hero who had risen from poverty, who was forced to leave school prematurely to support his mother and sisters, and who rose to fame solely by his own efforts. None of this is true.

Raffles’ father, Captain Benjamin Raffles, was a commander of vessels until the late 1790s, and lived until 1811. When Raffles left school around 1795, some 16 years earlier, his father was still living with the family. Raffles was privileged to have remained at a private school until he was 14 (most children then would have left school by age 11) and to have obtained a highly sought after position as an extra clerk at East India House.

Raffles owed much to the financial support and patronage of his wealthy uncle, Charles Hamond, who secured Raffles’ entry into Mansion House Boarding School and paved the way for his employment at India House, while his later career and status were propelled by his patron, Lord Minto, the Governor-General of Bengal. However, Boulger’s “facts” have become part of the myth surrounding Raffles and helped create an enduring fascination with the man. Boulger was scathingly dismissive of any role for Farquhar, declaring that Raffles was the sole founder of Singapore and wholly responsible for its development.3 Such views were accepted and repeated without question by subsequent biographers.

Farquhar’s role in Singapore has been defended in the past by eminent historians such as John Bastin, Mary Turnbull and Ernest Chew. Bastin wrote that Singapore’s early success “must be attributed generally to [Farquhar’s] fostering care and benevolent administration”. Mary Turnbull noted that Farquhar had nurtured the settlement through its precarious early years, while Ernest Chew argued that Farquhar had been neglected in the founding narratives of Singapore, contending that Farquhar had been “left behind” by Raffles to run the settlement and subsequently also “left behind” in history.4

(Right) A portrait of Sir Stamford Raffles presented by his nephew, W.C. Raffles Flint, to London’s National Gallery Portrait Gallery in 1859. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Although Farquhar’s role was periodically raised in the press and more recently included in the history curriculum of Singapore schools, the Raffles myth has prevailed. A group of students who re-assessed the roles of Raffles and Farquhar in 2007 could not have expressed it better, concluding that Raffles was “the real founder of Singapore as all the history textbooks say so”, and because he had a statue erected in his honour and an MRT station named after him whereas Farquhar had nothing.5

Indeed, landmarks in Singapore such as Farquhar Street, Mount Farquhar and Farquhar’s Strait have all disappeared.6 Singapore’s first and only Commandant and Resident suffered the converse of memorialisation: the “phenomenon of forgetting”,7 a phrase coined by the 20th-century French philosopher Paul Ricoeur.

Farquhar’s Accomplishments in Malacca

From as early as the 17th century, European trading companies competed for trade in the region. By the early 1800s, the British had secured trading posts at Penang and Bencoolen (Bengkulu) while the Dutch ruled Malacca, the Maluku islands and Java.

The British, however, came to occupy Malacca serendipitously as a result of the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1788, which stipulated that if a war should break out, either party could occupy the colonies of the other to protect them against enemy invasion. This occurred in 1793 when France, already at war with Britain, attacked the Dutch Republic. William V, the Dutch ruler was overthrown and fled to England in 1795. There, he ordered Dutch officials to hand their bases over to the British for safekeeping and to stop them from falling into French hands. The understanding was that the British would return these Dutch territories when peace was eventually restored.

Into this fractious scene entered Farquhar and Raffles. Farquhar and Raffles were employees of the powerful East India Company (EIC), formed at the turn of the 17th century ostensibly to trade with India and Southeast Asia, but which eventually became a powerful agent of British imperialism.

Farquhar first arrived in Malacca as an officer of the EIC in 1795 when the British occupied the Dutch port. He was appointed its Commandant in 1803, and in 1812, in recognition of his wide responsibilities, his title was changed to Commandant and Resident. It was in Malacca that Farquhar honed his skills as an administrator, the experience laying a strong foundation for his subsequent management of Singapore.

During Farquhar’s 15-year stint in Malacca, he was answerable to two lieutenant-governors and nine governors in Penang, all of whom were more than satisfied with his administration. Farquhar dramatically turned Malacca’s economy around, implemented British laws declaring the slave trade a felony, and fought for the town’s survival. It is implausible that Farquhar would have changed from being a competent ruler in Malacca to an incompetent one in Singapore.

Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the British were obliged to return Malacca to the Dutch. Merchants in Penang, whose trade had flourished during the British occupation of Malacca and Java, were worried that their inroads into new markets might be curtailed after the Dutch reclaimed their possessions. Along with Farquhar, the merchants pressed Colonel John Bannerman, the Governor of Penang, to protect British commercial interests in the Eastern Archipelago (present-day Indonesia).8

The Search for a New Site

Bannerman thus sent Farquhar to negotiate with rulers in the region, and in August 1818, he managed to secure a trade treaty with Sultan Abdul Rahman of the Johor Empire. Although the treaty gave Britain most favoured nation status, Farquhar knew that something more substantial was needed to protect British interests once the Dutch returned.

In 1816, Farquhar had advocated founding a new base south of the Straits of Malacca and now he urgently pushed to secure the Carimon Islands (Pulau Karimun), situated some 20 miles southwest of Singapore and commanding the entrance to the strait.9

Bannerman was unconvinced, citing the costs involved, but he did forward Farquhar’s suggestions to the Marquess of Hastings, the EIC’s new Governor-General who administered British interests in the Far East.

Hastings faced further pressure to act from the merchants in Calcutta and then from Raffles, who had arrived in the Indian city. Hastings decided to build upon the strong footing obtained by Farquhar’s commercial treaty and sent Raffles on a two-fold mission: first, to settle a dynastic dispute in Aceh, and then, to establish a new post at Rhio (Riau). Because of Farquhar’s experience and expertise, Hastings appointed him to take charge of any new post, but made him subordinate to Raffles, who was based in Bencoolen, Sumatra, at the time.10

Raffles and Farquhar met in Penang and on 19 January 1819, Raffles’ small fleet sailed for the Carimon Islands.11 As the islands proved unsuitable, Farquhar suggested Singapore as an alternative base.12 After Raffles and Farquhar stepped ashore on 28 January, Raffles, who had only recently contemplated Singapore as an option, realised that the island was an ideal spot to stake British claim.

But there was a problem. The island was part of the Johor Empire and its ruler, Sultan Abdul Rahman, had sworn allegiance to the Dutch. Raffles got around this by exploiting a dynastic dispute: he made a deal with the sultan’s older brother and rightful heir, Tengku Long, offering him the throne in return for permission to establish a post in Singapore. Tengku Long agreed and Raffles installed him as Sultan Hussein Mohamed Shah of Johor.

Raffles then signed a treaty with Sultan Hussein and Temenggong Abdul Rahman, the local chief of Singapore, on 6 February 1819. This treaty allowed the EIC to lease land for a trading post. It was tiny – extending only from Tanjong Katong to Tanjong Malang, and inland for about one mile. The rest of the island belonged to Malay nobles and even within the British post, British regulations did not apply inside their compounds.

Raffles did not purchase the island of Singapore, nor acquire it for Britain as often claimed. Indeed, the acquisition was far from guaranteed. After appointing Farquhar Resident and Commandant as ordered by Hastings, Raffles gave Farquhar a list of instructions and departed for Penang on 7 February 1819.

The Dutch were furious at Raffles’ actions. So was the British government which was engaged in negotiations with the Dutch over their respective spheres of influence in the East. The Dutch protested, and reports were received that they would retake Singapore by force. Although Bannerman tried to persuade Farquhar to leave at once, he refused to abandon Singapore: Farquhar knew this was Britain’s last chance to obtain a new base in the region.

In the meantime, Sultan Hussein and the Temenggong regretted having signed the treaty. They wrote to Sultan Abdul Rahman and to his viceroy asking for forgiveness and accused Raffles of having coerced them into signing it. Farquhar persuaded the nobles to retract their statements, and due to his early actions, the post remained in British hands – at least for the time being. However, Baron Godert van der Capellen, the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, continued to insist that Sultan Hussein had no right to allow the British to establish a post, and demanded that the British withdraw from Singapore.

Farquhar’s Work in Singapore

While the politicians argued, Farquhar got down to work. Few of Raffles’ supporters have given Farquhar credit for building the settlement from scratch with precious little money, and limited manpower and resources. Yet Farquhar achieved the near impossible: he cleared over 650,000 square yards of jungle and swamp, built a reservoir and aquaduct, defence works, accommodation and facilities for the troops, and roads and small bridges. The population grew significantly as men from Malacca who knew and respected Farquhar flocked to Singapore to find work or to trade, bringing with them the money and muscle that were vital to the growth of the settlement.

The wealthy businessman Tan Che Sang, who had formed a close rapport with Farquhar in Malacca, followed him to Singapore, bringing capital for investment and trade as well as leadership expertise. Entrepreneurs such as Tan Tock Seng and Tan Kim Seng who similarly moved from Malacca, played vital roles in cementing Singapore’s position as a commercial centre.

Raffles made a short visit to Singapore in late May 1819. Delighted at its metamorphosis, he commented on the numerous ships in the harbour and the large kampongs (villages). Proudly he claimed to the Duchess of Somerset:

“[Singapore] is a child of my own, and I have made it what it is. You may easily conceive with what zeal I apply myself to the clearing of forests, cutting of roads, building of towns, framing of laws, &c &c”.13

But in fact, Raffles had not been in Singapore all this while: the improvements to the island’s economy and infrastructure were all due to Farquhar’s able leadership. Farquhar administered Singapore for nearly four-and-a-half years between 7 February 1819 and 1 May 1823, while Raffles was present for barely eight months during those years: from 31 May to 27 June 1819 and returning on 10 October 1822.

During Raffles’ absence, Farquhar turned the fledgling port into a successful settlement. Visiting merchants and sea captains praised the conditions and prospects of Singapore. Letters sent to Calcutta described the settlement as “most flourishing”, affirming that the shore was “crowded with life, bustle and activity and the harbour is filled with square-rigged vessels and prows”.14 Visitors enthusiastically wrote of its increasing population, the cleared lands, the roads, the buildings and the busy port with its burgeoning trade in regional produce. They were impressed by the large neatly laid out cantonment, the extensive Chinese and Bugis kampongs.15 Even William Jack, a sycophant of Raffles, praised the great progress of the settlement.16

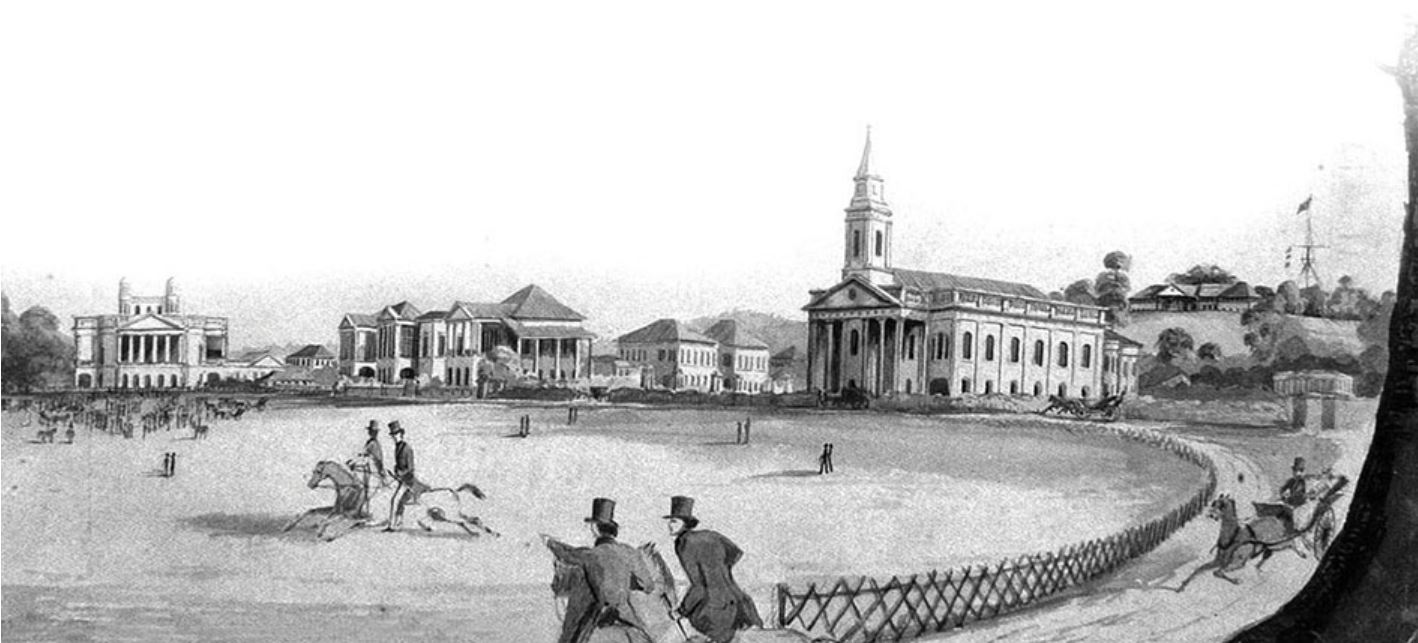

By late 1821, Singapore was a successful commercial settlement of some 5,000 settlers. The plain at Kampong Glam was marked out for the European town, with roads neatly laid out.17 Land allotments were numbered, registered and marked on a map and the major streets were named. Buildings, including a boat office, engineers’ park, three hospitals and the Resident’s bungalow were erected and a spice plantation established.18

Over 15 miles of road were laid, nearly half of which were carriage roads between 12 and 16 yards wide. Farquhar ordered further dredging of the Rochor River, making it more navigable. This led to an expansion of the Bugis village along the river banks as the community took advantage of the better facilities for trade and boat repairs.19

Farquhar passed measures to ensure the health and safety of residents, in particular to combat fire and disease. As most buildings were constructed from timber with attap (thatched) roofs, fire could easily spread. So Farquhar instructed residents to store as much water as possible to fight such a threat. To combat the outbreak of disease, especially cholera, residents were asked to keep their houses and yards clean. Farquhar also forbade residents from throwing rubbish onto the road, ordering that it be dumped in designated areas.20 The modern-day image of Singapore as a clean city has a long history, beginning with Farquhar.

As well as building the town infrastructure, Farquhar was proactive in establishing Singapore as a trading centre. He wrote to rulers in the region, encouraging them to trade with Singapore – taking pains to emphasise its facilities, its extensive roadstead and the gateway it offered to the Eastern Archipelago. He also highlighted Singapore’s free trade status – although Raffles intended this to be only a temporary measure. Farquhar opened up trade with Brunei, and hoped to extend it to Siam, and as far as Japan. He envisaged Singapore as the new emporium of the East, outdoing even Batavia (Jakarta).21

Indeed, by 1822, Singapore’s trade had reached $8 million – mainly in regional produce. Opium topped the list followed by Indian textiles, silver coins and tin. But Farquhar’s ambitions were hampered by reality. Hastings doubted the legality of Raffles’ treaty with Sultan Hussein and was worried that the settlement would be returned to the Dutch. Hence, in October 1819, Hastings imposed severe reductions on costs and personnel, and ordered that no new construction work was to take place in Singapore.

Other issues arose. As the population increased, so did the crime rate – largely due to gambling and opium smoking. Farquhar planned to rein in these activities by selling licences for the sale of arrack (a local alcoholic spirit) and opium, and for the running of gaming houses.22 This would also generate revenue which he could use to pay for a much-needed police force.

Contrary to what has been written, Farquhar did not introduce cock fighting licences, a charge that is often levelled against him. In fact, Farquhar abhorred the sport and had refused to allow cock fighting licences in Malacca. In Singapore, he “strictly prohibited” cock fighting except on specific Malay festivals, and then only with his permission. It was John Crawfurd, who succeeded Farquhar as the next Resident of Singapore in June 1823, who first allowed a cock fighting licence to be issued in the settlement.23

Initially, Raffles was wary of introducing opium licences, fearing it would adversely impact the EIC’s opium trade. He saw Singapore as an outlet for selling opium throughout the region and was determined that the EIC’s opium trade be “protected and offered every facility”.24 However, despite his own concerns, Raffles issued instructions for the introduction of opium licences, declaring that “a certain number of houses may be licensed for the sale of madat or prepared opium”.25

Raffles not only instructed Farquhar to auction the licences and re-auction them “every three months until further orders”, but he also took a 5 percent commission on each opium licence for himself.26 Raffles’ supporters have distanced his role in the opium licensing scheme by accusing Farquhar of introducing these licences by wilfully disobeying Raffles’ orders. Ironically, the opium farms “introduced” by Farquhar and sanctioned by Raffles became Singapore’s largest single source of revenue from 1824 until 1910.27

While Farquhar has been acknowledged as the founder of the first police force in the settlement, several of his other achievements have been overlooked. For example, it was Farquhar who rediscovered Singapore’s deep water harbour, recognising its commercial and strategic significance, and arranging for its depths to be measured.28 Farquhar named it New Harbour, a name that remained until 1900 when the harbour was dedicated to Admiral Henry Keppel.29

Farquhar undertook the first survey of the island, later compiling a map that was forwarded to Raffles. He also drew up a schematic town plan in 1821, as well as a detailed map showing the town, New Harbour and adjoining islands which he presented to the EIC.30 He began the practice of recording Singapore’s daily temperature and pressure readings, maintaining these for two years and providing a benchmark for comparisons today.31

Farquhar also established a spice plantation and the first botanical garden, experimenting with the cultivation of pepper, coffee, spices and cotton. Although Farquhar was following Raffles’ orders, the success of these gardens owed much to Farquhar’s keen interest in natural history. Later, concerned that Raffles was selling large plots of land to the residents, Farquhar reserved valuable ground near the shoreline for military use, land that eventually became the Esplanade (and known as the Padang today).32

Farquhar established a prototype post office, which Raffles refined into an official Post Office in 1823, after receiving practical advice from Farquhar.33 Just as he had done in Malacca, Farquhar encouraged the work of missionaries, and helped them to set up Singapore’s first school.34 Having laid the foundation stone of the Anglo-Chinese College in Malacca in November 1818, Farquhar was similarly involved in the establishment of the Singapore Institution (precursor of today’s Raffles Institution). He was its President and also a trustee and patron, as well as a generous contributor to its subscription fund.

On his own initiative and risking censure from Raffles and Hastings, Farquhar granted asylum to Prince Belawa and 500 of his Bugis followers who had fled from the Dutch in Rhio. Despite angry protests by the Dutch, Farquhar stood his ground, and Raffles and Hastings supported this decision.35 The Bugis established themselves along Rochor River as traders and boat builders, and the community proved a great asset to Singapore. The Bugis remained grateful for Farquhar’s resolve as seen in their farewell address to him.36

While Farquhar was expediently developing Singapore, Raffles remained in Bencoolen and took only periodic interest in the settlement. He was most tardy in replying to Farquhar’s letters, even urgent ones, and seemed to hinder rather than support the work Farquhar was doing. Returning in October 1822 after three-and-a-half years’ absence, Raffles was elated with the rapid progress of Singapore, telling the Duchess of Somerset that:

“Here is all life and activity; and it would be difficult to name a place on the face of the globe, with brighter prospects or more present satisfaction. In little more than three years it has risen from an insignificant fishing village, to a large and prosperous town.”37

All this Raffles attributed to the “simple, but almost magic result” of freedom of trade – with no mention of Farquhar’s instrumental role.38

Even so, Raffles decided to demolish much of the town and remodel it according to his new plans. By this stage, he was in poor health and intended to return to England by mid-1824. Believing that Britain would retain Singapore, Raffles saw that his last chance to retire in glory was to reclaim Singapore as his own.

Raffles had earlier set aside land at East Beach (Kampong Glam) for the European merchants, but they were most unhappy as the site was unsuitable for loading and unloading goods. Instead, the merchants wanted to build their godowns along the north bank of Singapore River − land that Raffles had reserved for the government. Aware that trade was vital for Singapore’s future, Farquhar had allowed the merchants to provisionally build warehouses there. As he later explained, had he not done so, Singapore would have “completely withered in the bud”.39

Upset by Farquhar’s actions, Raffles complained to Hastings that his subordinate had deviated from instructions by allowing construction along the north bank, claiming that he would have to demolish these buildings and several others at great cost to the government.40

Realising that his original orders to build on East Beach were impractical, Raffles then sought another location. He chose the swampy south bank of the river, where he had ordered the Chinese to establish their kampong in 1819. Disregarding the distressed pleas of the scores of Chinese whom he had settled there, as well as the need for financial prudence, which he had so impressed upon Farquhar, Raffles ordered the swamp to be filled in to form a new commercial precinct.41

The relationship between the two men grew more acrimonious. Raffles continued to undermine Farquhar’s reputation by sending letters to Hastings making accusations against Farquhar. He repeated his earlier complaints that Farquhar had overspent government funds, but later withdrew that criticism.42 Raffles later asked his friend Dr Nathaniel Wallich to hint to Hastings that Farquhar had illegally acquired large areas of land, but later retracted that allegation. In fact, after admitting that he had been misled over the extent of Farquhar’s land acquisitions, Raffles went on to authorise him a grant of some 150 acres.43

Raffles further claimed that Farquhar had not provided a detailed account of the land grants he had allotted, and favoured certain individuals when granting land. In contrast, Raffles selected the best allotments for his family and friends, and allowed his brother-in-law William Flint to build on reserved land.44 Although Farquhar sent detailed despatches and documents to Hastings that clearly refuted those charges, the seeds of doubt had been sown.45

Raffles began to sideline Farquhar. He excluded Farquhar from his new Town Committee that he had set up in October 1822, and instead relied on the inexperienced Philip Jackson for engineering advice. In February 1823, Raffles took Farquhar’s place at the weekly Resident’s court.46 Despite these and other rebuffs, Farquhar assured Raffles of his full cooperation, gave advice when asked, and allowed the committee to use his maps.

Farquhar’s and Raffles’ differing attitudes on the status of Singapore further strained relations between them. Raffles saw Singapore as a British port, while Farquhar regarded it as a Malay port that belonged to the Malay rulers. Farquhar insisted on abiding by the terms of the treaty signed by Sultan Hussein and the Temenggong on 6 February 1819, without which Singapore could not have been founded, as well as the arrangements Raffles and he had signed with the Malay rulers on 26 June 1819.

Farquhar expressed concern when Raffles began to sell land, pointing out that Raffles had no authority to do so as the land rightfully belonged to the Malays. Raffles interpreted this as another instance of Farquhar’s opposition to his plans.

Raffles wrote to Hastings on 11 January 1823, stating that he did not consider Farquhar capable of running Singapore after his own resignation, when Singapore would fall directly under the Bengal government’s supervision. Hence, he wanted Farquhar quickly replaced by “a more competent” local authority.47 Yet the very next day Raffles wrote to his cousin, ecstatic at the progress Singapore had made under Farquhar:

“The progress of my new settlement is in every way most satisfactory, and it would gladden your heart to witness the activity and cheerfulness which prevails throughout. Every day brings us new settlers, and Singapore has already become a great emporium. Houses and warehouses are springing up in every direction.”48

Despite that praise, Raffles wrote two further despatches to Bengal, accusing Farquhar of mismanagement, incompetence and other irregularities.

On 1 May 1823, Raffles dismissed Farquhar as Resident and took over control of Singapore.49 He had no authority to do so as Hastings was the one who had appointed Farquhar.50 Feeling humiliated, Farquhar protested to the Bengal government. However, swayed by Raffles’ despatches, but at the same time concerned at the lack of evidence sustaining his accusations, the government appointed John Crawfurd to take charge. Upon Crawfurd’s arrival, Raffles dismissed Farquhar as Commandant.51 This second dismissal was also without authority and without due cause.

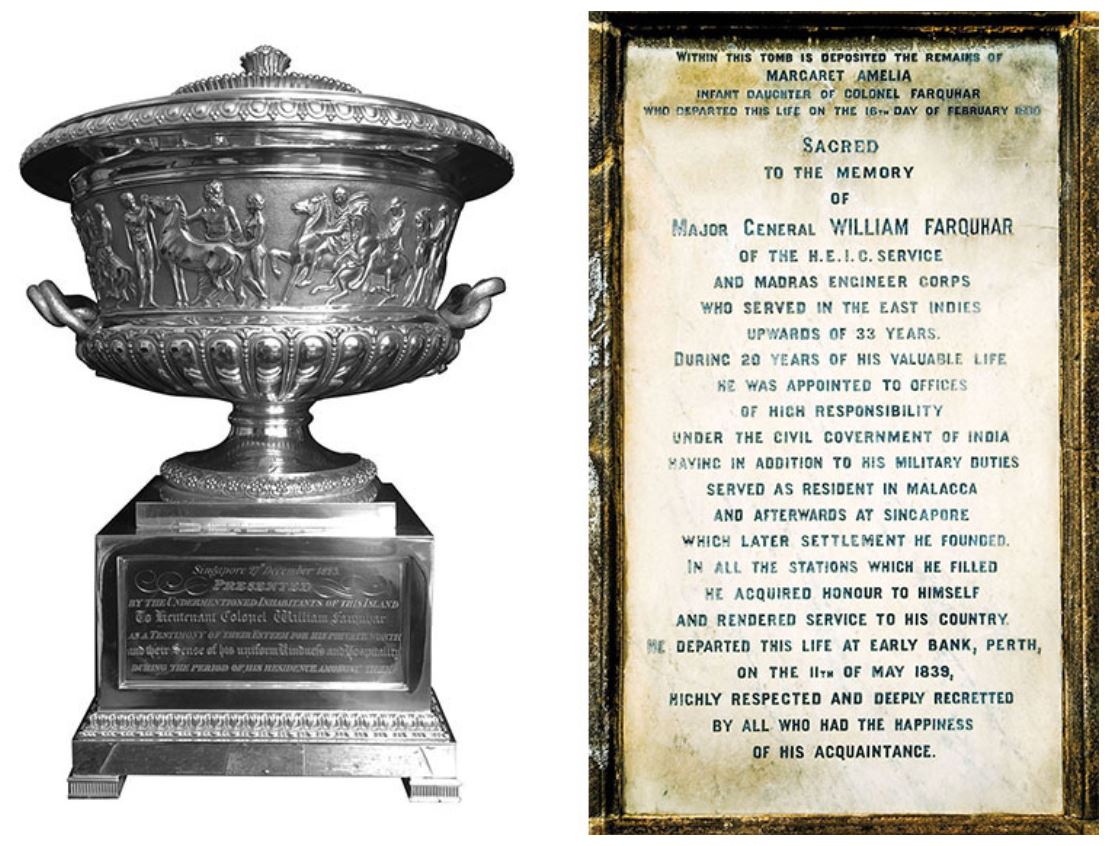

Farquhar left Singapore on 28 December 1823, embittered by his unjustified fall from grace. He received heartfelt farewell addresses from the Bugis, Chinese and Indian communities who showed their deep affection and respect for him, and their sense of loss at his departure. The European merchants were more circumspect in their written address, but still collected $3,000 for a farewell gift. The Chinese raised $700 for their own gift. This money paid for silverware which Farquhar later received in London: an elegant epergne from the Chinese, and a magnificently engraved cup from the European and Armenian merchants.

(Right) The epitaph on William Farquhar’s tombstone inside his mausoleum at Greyfriars Burial Ground in Perth, Scotland, bears testament to his contributions as “Resident in Malacca and afterwards at Singapore which later settlement he founded”. © Philip Game, photographersdirect.com.

In London, Farquhar composed a Memorial to the Court of Directors complaining of his illegal and unjustified dismissal, and petitioned to be reinstated.52 It was a war of words with Raffles battling for his pension, and Farquhar for his reputation. In the end, Farquhar lost.53

EIC protocol, the changing political scene and, above all, Raffles’ misrepresentations and untruths prevailed. Farquhar’s friend John Palmer had foreshadowed the final outcome, warning Farquhar that even if he were acquitted of the charges laid against him, he would not obtain redress. Palmer knew that the EIC would have to “condemn itself” in order to do justice to Farquhar, and that would not happen.54

Farquhar deserves as much credit as Raffles in the founding of modern Singapore. His vital role in the events leading to the establishment of a foothold on the island cannot be brushed aside. Although Raffles raised the British flag, it was Farquhar who kept it flying despite intense pressure to abandon the post. Above all, he developed the settlement into such a commercial success that in 1824, Britain decided to retain it.

For various reasons, Farquhar lost his rightful place in the history of Singapore. The time to set the record straight is all the more important as the city-state marks the 200th year of its founding in 2019.

| This essay is based on the author’s PhD thesis, “Image is All: Farquhar, Raffles and the Founding and Early Development of Singapore”, as well as her book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles’ Shadow. The book is on sale and is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.5703 WRI-[HIS] and SING 959.5703 WRI) |

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, 'William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles’ Shadow, was published in May 2017.

Dr Nadia Wright, a retired teacher and now active historian, lives in Melbourne. She specialises in the colonial history of Singapore and Armenians in Southeast Asia. Her book, 'William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping Out from Raffles’ Shadow, was published in May 2017.

Notes

-

Farquhar, W. (1830, May–August). The establishment of Singapore. The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, 2, pp. 142. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Boulger, D. C. (1999).The life of Sir Stamford Raffles. Amsterdam: The Pepin Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 BOU) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2005). William Farquhar first resident and commandant of Singapore (p. 27). Eastbourne: Privately printed. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.503 BAS-[JSB]); Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819–1988 (p. 30). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR); Chew, E.C.T. (2002, Apr–Jun). The man who Raffles left behind: William Farquhar (1774–1839), Raffles Town Club, 7. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.503 RAF-JSB]) ↩

-

Who was the founder of Singapore? (2007, July 3). Retrieved from Victoria’s School History blogspot. ↩

-

Although some 380 streets in Singapore are named after government officials and prominent people from the colonial era, none commemorate Farquhar. Farquhar Street, which ran parallel to Rochor Road, disappeared in 1994 after roads in the area were expunged. Mt Farquhar, which was a low hill near the General Hospital, has long been levelled. Farquhar’s Straits appeared as an alternative name to the Old Straits of Singapore in the first map of Singapore but was short-lived. ↩

-

Ricoeur, P. (2004). Memory, history, forgetting (p. 284). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: SING 128.3 RIC) ↩

-

The Eastern Archipelago refers to the islands that form much of today’s Indonesia – Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok, Bangka, Belitun, Maluku Islands and Borneo. ↩

-

Memorandums, vol. 10, SSFR; Farquhar to Bannerman, 6 September 1818, vol. 67, SSFR. ↩

-

Hastings to Bannerman, 28 November 1818, vol. 182A, SSFR; Adam to Farquhar, 28 November 1818, L. 10, East India Company, Straits Settlements Records, Government of the Colony of Singapore, Raffles National Library Archives, 1961. Microfilm, Monash University. Hereafter these records are cited as SSR. ↩

-

Raffles had disobeyed the sequence of Hastings’ instructions which caused an irrevocable rift with Bannerman. ↩

-

Elout to Capellen, 25 August 1818, in Wurtzburg, C. (1954). Raffles of the eastern isles (p. 451). London, Hodder and Stoughton. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.570210924 WUR); Crawfurd, J. (1828). Journal of an embassy to the courts of Siam and Cochin China (p. 565). London: Henry Colburn. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9044 CRA). It is noteworthy that Raffles never claimed that he had specifically suggested Singapore. His first choices were Rhio and Banca as he wanted to control the Sunda Straits. ↩

-

Raffles to the Duchess of Somerset, 11 June 1819. See Raffles, S. (1991). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (p. 383). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 RAF-[HIS]) ↩

-

Singapore. (1820, January–June). The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, 9, p. 402. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Singapore. (1820, July–December). The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, 10, pp. 292–293. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Jack to Wallich, 8 June 1819, in Burkill, I.H. (1916, July). William Jack’s letters to Nathaniel Wallich, 1819–1821. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 73 , p. 178. (Call no.: RRARE 582.09595 JAC-[JSB]) ↩

-

Historical sketch of the settlement of Singapore. (1823, July–December). The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, 16, pp. 28–29. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 18 June 1819, NAB 1668; Farquhar to Raffles, 17 April 1821, L. 4, SSR Buckley, C.B. (1965). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (pp. 68–69). Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 17 April 1821, L. 4, SSR. ↩

-

Badriyah Haji Salleh. (1999). Warkah al-Ikhlas 1818–182 (pp. 28–29, 155–156). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay RSING 091 WAR) ↩

-

Dr Annabel Teh Gallop, a scholar on Malay works, attributes Farquhar’s success in attracting regional commerce to Singapore to his careful diplomatic correspondence. See Gallop, A. (1994). The legacy of the Malay letter = Warisan warkah Melayu (p. 167). London: British Library for the National Archives of Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING q899.286 GAL) ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 2 November 1819, L. 10, SSR. ↩

-

Public Advertisement No. 8, 1 May 1820; Appendix to Memorial of Lt Col. Farquhar, 2 April 1825, IOR MS No. 542, p. 155, SSR; Notice, 23 August 1823, L. 19, SSR. ↩

-

Raffles to Mackenzie, 20 December 1819, enclosed in Raffles to Dart, 28 December 1819, vol. 50, Sumatra Factory Records, East India Company, National University of Singapore; India Office Library and Records. London: Recordak Microfilm Service. 1960. Monash University. ↩

-

Raffles to Travers, 20 March 1820, vol. 50, Sumatra Factory Records. ↩

-

Jennings to Farquhar, 15 August 1820, L. 4, SSR; Accountant General’s office, 8 March 1826, vol. 71, Java Factory Records, East India Company, London, Recordak Microfilm Services, 1956. Microfilm, Monash University. Hereafter referred to as JFR. ↩

-

Trocki, C. (2006). Singapore: Wealth, power and the culture of control (p. 20). London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 TRO-[HIS] ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 2 September 1819, L. 10, SSR. Raffles made no response to the news of this harbour leading Farquhar to again inform him of its value; Farquhar to Raffles, 21 July 1820, L. 4 SSR. ↩

-

His honour’s folly. (1900, April 19). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 17 April 1821, L. 4; Farquhar to Hull, 6 November 1822, L. 9, SSR; Farquhar to Raffles, 2 June 1823, L. 15, SSR; Court Minutes, 25 May 1825, IOR B/178: 92. ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 11 January 1821, L. 4, SSR; Farquhar to Mackenzie, 9 March 1822, L. 7, SSR; Farquhar, W. (1827). Thermometrical and barometrical tables. Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1(2), pp. 585–586. (Call no.: RRARE 551.609595 FAR-[JSB]) ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 6 December 1822, L. 6, SSR. ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 24 January 1823, L. 13, SSR; Peterson, (1952, July 19). Post office was set up in nine days. The Singapore Free Press, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Farquhar to Milton, 19 May 1820; Farquhar to Raffles, 23 June 1820, L. 10, SSR. ↩

-

Farquhar to Raffles, 23 February 1820, L. 10, SSR; Raffles to Farquhar, 2 May 1820, L. 4, SSR. ↩

-

Translation of an address from His Highness Arong Belawa, the Soolawatan (or Captain of the Bugis) and the Bugis inhabitants of Singapore, to Lieut. Col. Farquhar. Thursday 25th day of Dec. 1823. Prince of Wales Island Gazette, 24 January 1824. ↩

-

Raffles to the Duchess of Somerset, 30 November 1822. See Raffles, 1991, p. 525. ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 13 November 1822, L. 9, SSR. ↩

-

Raffles to Bengal, 9 August 1821, vol. 71, JFR, East India Company, London, Recordak Microfilm Services, 1956. Microfilm, Monash University; Swinton to Raffles, 29 March 1823, L. 18, SSR ↩

-

Farquhar to Hull, 4 December 1822, L. 6, SSR; Hull to Farquhar, 4 December 1822, L. 11, SSR; Farquhar to Hull, 5 November 1822, L. 9, SSR; Farquhar to Sherer, 28 December 1822, L. 11, SSR; Farquhar to Hull, 5 April 1823, L. 15, SSR. ↩

-

Raffles to Bengal, 1 January 1823, vol. 71, JFR. ↩

-

Hull to Farquhar, 4 February 1823, L. 17, SSR. ↩

-

Raffles to Farquhar, 26 June 1819, L 10, SSR ↩

-

Farquhar to de la Motte, 30 April 1822, L. 7, SSR; Farquhar to Raffles, 17 April 1821, L. 4, SSR; Farquhar to Raffles, 5 November 1822, L. 9, SSR. ↩

-

Jackson to Hull, 29 October 1822, L. 9, SSR; Hull to Farquhar, 7 February 1823, L. 17. ↩

-

Raffles to Swinton, 11 January 1823, vol. 71, JFR. ↩

-

Raffles to Rev. Dr Raffles, 12 January 1823. See Boulger, 1999, pp. 331–332. ↩

-

Hull to Farquhar, 28 April 1823, L. 17, SSR. ↩

-

Adam to Farquhar, 28 November 1818, L. 10, SSR. ↩

-

Hull to Farquhar, 22 May 1823, L. 19, SSR. ↩

-

The Memorial of William Farquhar, and Appendix to the Memorial, Home Miscellaneous Series no. 541 India Office Records, British Library. ↩

-

Raffles too suffered as the EIC refused to grant him his anticipated pension. ↩

-

Palmer to Farquhar, February 1824, Palmer to Coombs, 11 February 1824. See Wurtzburg, 1954, p. 688. ↩